International System of Units

The SI base units

| Symbol | Name | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| A | ampere | electric current |

| K | kelvin | temperature |

| s | second | time |

| m | metre | length |

| kg | kilogram | mass |

| cd | candela | luminous intensity |

| mol | mole | amount of substance |

The International System of Units (SI, abbreviated from the French Système international (d'unités)) is the modern form of the metric system, and is the most widely used system of measurement. It comprises a coherent system of units of measurement built on seven base units, which are the ampere, kelvin, second, metre, kilogram, candela, mole, and a set of twenty prefixes to the unit names and unit symbols that may be used when specifying multiples and fractions of the units. The system also specifies names for 22 derived units, such as lumen and watt, for other common physical quantities.

The base units are derived from invariant constants of nature, such as the speed of light in vacuum and the triple point of water, which can be observed and measured with great accuracy, and one physical artefact. The artefact is the international prototype kilogram, certified in 1889, and consisting of a cylinder of platinum-iridium, which nominally has the same mass as one litre of water at the freezing point. Its stability has been a matter of significant concern, culminating in a revision of the definition of the base units entirely in terms of constants of nature, scheduled to be put into effect on 20 May 2019.[1]

Derived units may be defined in terms of base units or other derived units. They are adopted to facilitate measurement of diverse quantities. The SI is intended to be an evolving system; units and prefixes are created and unit definitions are modified through international agreement as the technology of measurement progresses and the precision of measurements improves. The most recent derived unit, the katal, was defined in 1999.

The reliability of the SI depends not only on the precise measurement of standards for the base units in terms of various physical constants of nature, but also on precise definition of those constants. The set of underlying constants is modified as more stable constants are found, or may be more precisely measured. For example, in 1983 the metre was redefined as the distance that light propagates in vacuum in a given fraction of a second, thus making the value of the speed of light in terms of the defined units exact.

The motivation for the development of the SI was the diversity of units that had sprung up within the centimetre–gram–second (CGS) systems (specifically the inconsistency between the systems of electrostatic units and electromagnetic units) and the lack of coordination between the various disciplines that used them. The General Conference on Weights and Measures (French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures – CGPM), which was established by the Metre Convention of 1875, brought together many international organisations to establish the definitions and standards of a new system and standardise the rules for writing and presenting measurements. The system was published in 1960 as a result of an initiative that began in 1948. It is based on the metre–kilogram–second system of units (MKS) rather than any variant of the CGS. Since then, the SI has been adopted by all countries except the United States, Liberia and Myanmar.[2]

Contents

1 Units and prefixes

1.1 Base units

1.2 Derived units

1.3 Prefixes

1.4 Non-SI units accepted for use with SI

1.5 Common notions of the metric units

2 Lexicographic conventions

2.1 Unit names

2.2 Unit symbols and the values of quantities

2.2.1 General rules

2.2.2 Printing SI symbols

2.2.3 Examples of the variety of symbols in use around the world for kilometres per hour

3 International System of Quantities

4 Realisation of units

5 Evolution of the SI

5.1 Changes to the SI

5.2 2019 redefinitions

6 History

6.1 The improvisation of units

6.2 Metre Convention

6.3 The cgs and MKS systems

6.4 The Practical system of units

6.5 Birth of the SI

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Units and prefixes

The International System of Units consists of a set of base units, derived units, and a set of decimal-based multipliers that are used as prefixes.[3]:103–106 The units, excluding prefixed units,[Note 1] form a coherent system of units, which is based on a system of quantities in such a way that the equations between the numerical values expressed in coherent units have exactly the same form, including numerical factors, as the corresponding equations between the quantities. For example, 1 N = 1 kg × 1 m/s2 says that one newton is the force required to accelerate a mass of one kilogram at one metre per second squared, as related through the principle of coherence to the equation relating the corresponding quantities: F = m × a.

Derived units apply to derived quantities, which may by definition be expressed in terms of base quantities, and thus are not independent; for example, electrical conductance is the inverse of electrical resistance, with the consequence that the siemens is the inverse of the ohm, and similarly, the ohm and siemens can be replaced with a ratio of an ampere and a volt, because those quantities bear a defined relationship to each other.[Note 2] Other useful derived quantities can be specified in terms of the SI base and derived units that have no named units in the SI system, such as acceleration, which is defined in SI units as m/s2.

Base units

The SI base units are the building blocks of the system and all the other units are derived from them. When Maxwell first introduced the concept of a coherent system, he identified three quantities that could be used as base units: mass, length and time. Giorgi later identified the need for an electrical base unit, for which the unit of electric current was chosen for SI. Another three base units (for temperature, amount of substance and luminous intensity) were added later.

| Unit name | Unit symbol | Dimension symbol | Quantity name | Definition[n 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

metre | m | L | length |

|

kilogram[n 2] | kg | M | mass |

|

second | s | T | time |

|

ampere | A | I | electric current |

|

kelvin | K | Θ | thermodynamic temperature |

|

mole | mol | N | amount of substance |

|

candela | cd | J | luminous intensity |

|

The Prior definitions of the various base units in the above table were made by the following authorities:

All other definitions result from resolutions by either CGPM or the CIPM and are catalogued in the SI Brochure. | ||||

The early metric systems defined a unit of weight as a base unit, while the SI defines an analogous unit of mass. In everyday use, these are mostly interchangeable, but in scientific contexts the difference matters. Mass, strictly the inertial mass, represents a quantity of matter. It relates the acceleration of a body to the applied force via Newton's law, F = m × a: force equals mass times acceleration. A force of 1 N (newton) applied to a mass of 1 kg will accelerate it at 1 m/s2. This is true whether the object is floating in space or in a gravity field e.g. at the Earth's surface. Weight is the force exerted on a body by a gravitational field, and hence its weight depends on the strength of the gravitational field. Weight of a 1 kg mass at the Earth's surface is m × g; mass times the acceleration due to gravity, which is 9.81 newtons at the Earth's surface and is about 3.5 newtons at the surface of Mars. Since the acceleration due to gravity is local and varies by location and altitude on the Earth, weight is unsuitable for precision measurements of a property of a body, and this makes a unit of weight unsuitable as a base unit.

Derived units

The derived units in the SI are formed by powers, products or quotients of the base units and are unlimited in number.[3]:103[4]:3 Derived units are associated with derived quantities; for example, velocity is a quantity that is derived from the base quantities of time and length, and thus the SI derived unit is metre per second (symbol m/s). The dimensions of derived units can be expressed in terms of the dimensions of the base units.

Combinations of base and derived units may be used to express other derived units. For example, the SI unit of force is the newton (N), the SI unit of pressure is the pascal (Pa)—and the pascal can be defined as one newton per square metre (N/m2).[9]

Quantity | Symbol | SI derived unit | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

area | A | square metre | m2 |

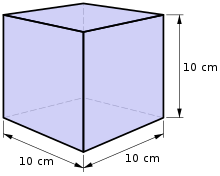

volume | V | cubic metre | m3 |

speed, velocity | v | metre per second | m⋅s−1 |

acceleration | a | metre per second squared | m⋅s−2 |

wavenumber | σ, ṽ | reciprocal metre | m−1 |

density | ρ | kilogram per cubic metre | kg⋅m−3 |

surface density | ρA | kilogram per square metre | kg⋅m−2 |

specific volume | v | cubic metre per kilogram | m3⋅kg−1 |

current density | j | ampere per square metre | A⋅m−2 |

magnetic field strength | H | ampere per metre | A⋅m−1 |

concentration | c | mole per cubic metre | mol⋅m−3 |

mass concentration | ρ, γ | kilogram per cubic metre | kg⋅m−3 |

luminance | Lv | candela per square metre | cd⋅m−2⋅ |

refractive index | n | one | 1 |

relative permeability | μr | one | 1 |

| Namenote 1 | Symbol | Quantity | In other SI units | In SI base units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

radiannote 2 | rad | plane angle | 1 | (m⋅m−1) |

steradiannote 2 | sr | solid angle | 1 | (m2⋅m−2) |

hertz | Hz | frequency | s−1 | |

newton | N | force, weight | kg⋅m⋅s−2 | |

pascal | Pa | pressure, stress | N/m2 | kg⋅m−1⋅s−2 |

joule | J | energy, work, heat | N⋅m = Pa⋅m3 | kg⋅m2⋅s−2 |

watt | W | power, radiant flux | J/s | kg⋅m2⋅s−3 |

coulomb | C | electric charge or quantity of electricity | s⋅A | |

volt | V | voltage (electrical potential), emf | W/A | kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−1 |

farad | F | capacitance | C/V | kg−1⋅m−2⋅s4⋅A2 |

ohm | Ω | resistance, impedance, reactance | V/A | kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−2 |

siemens | S | electrical conductance | Ω−1 | kg−1⋅m−2⋅s3⋅A2 |

weber | Wb | magnetic flux | V⋅s | kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅A−1 |

tesla | T | magnetic flux density | Wb/m2 | kg⋅s−2⋅A−1 |

henry | H | inductance | Wb/A | kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅A−2 |

degree Celsius | °C | temperature relative to 273.15 K | K | |

lumen | lm | luminous flux | cd⋅sr | cd |

lux | lx | illuminance | lm/m2 | m−2⋅cd |

becquerel | Bq | radioactivity (decays per unit time) | s−1 | |

gray | Gy | absorbed dose (of ionising radiation) | J/kg | m2⋅s−2 |

sievert | Sv | equivalent dose (of ionising radiation) | J/kg | m2⋅s−2 |

katal | kat | catalytic activity | mol⋅s−1 | |

| Notes 1. The table is ordered so that a derived unit is listed after the units upon which its definition depends. 2. The radian and steradian are defined as dimensionless derived units. | ||||

| Namenote 1 | Symbol | Quantity | In other SI units | In SI base units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pascal second | dynamic viscosity | |||

| newton metre | moment of force | |||

| newton per metre | surface tension | |||

| radian per second | angular velocity | |||

| radian per second squared | angular acceleration | |||

| watt per square metre | heat flux density | |||

| joule per kelvin | heat capacity, entropy | |||

| joule per kilogram kelvin | specific heat capacity, specific entropy | |||

| joule per kilogram | specific energy | |||

| watt per metre kelvin | thermal conductivity | |||

| joule per cubic metre | energy density | |||

| volt per metre | electric field strength | |||

| coulomb per cubic metre | electric charge density | |||

| coulomb per square metre | surface charge density, electric flux density | |||

| farad per metre | permittivity | |||

| henry per metre | permeability | |||

| joule per mole | molar energy | |||

| joule per mole kelvin | molar heat capacity, molar entropy | |||

| coulomb per kilogram | exposure | |||

| gray per second | absorbed dose rate | |||

| watt per steradian | radiant intensity | |||

| watt per square metre steradian | radiance | |||

| katal per cubic metre | catalytic activity concentration | |||

| Notes 1. The table is ordered so that a derived unit is listed after the units upon which its definition depends. | ||||

Prefixes

Prefixes are added to unit names to produce multiples and sub-multiples of the original unit. All of these are integer powers of ten, and above a hundred or below a hundredth all are integer powers of a thousand. For example, kilo- denotes a multiple of a thousand and milli- denotes a multiple of a thousandth, so there are one thousand millimetres to the metre and one thousand metres to the kilometre. The prefixes are never combined, so for example a millionth of a metre is a micrometre, not a millimillimetre. Multiples of the kilogram are named as if the gram were the base unit, so a millionth of a kilogram is a milligram, not a microkilogram.[3]:122[10]:14 When prefixes are used to form multiples and submultiples of SI base and derived units, the resulting units are no longer coherent.[3]:7

The BIPM specifies twenty prefixes for the International System of Units (SI):

SI prefixes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

^ Prefixes adopted before 1960 already existed before SI. 1873 was the introduction of the CGS system.

Non-SI units accepted for use with SI

Many non-SI units continue to be used in the scientific, technical, and commercial literature. Some units are deeply embedded in history and culture, and their use has not been entirely replaced by their SI alternatives. The CIPM recognised and acknowledged such traditions by compiling a list of non-SI units accepted for use with SI, which are grouped as follows:[3]:123–129[10]:7–11[Note 4]

The litre is classed as a non-SI unit accepted for use with the SI.

The litre differs from the SI coherent unit m3 by a factor 0.001 and is therefore not a coherent unit of measure with respect to SI.

Non-SI units accepted for use with the SI (Table 6):

- Certain units of time, angle, and legacy non-SI units have a long history of consistent use. Most societies have used the solar day and its non-decimal subdivisions as a basis of time and, unlike the foot or the pound, these were the same regardless of where they were being measured. The radian, being 1/2π of a revolution, has mathematical advantages but it is cumbersome for navigation[citation needed], and, as with time, the units used in navigation are largely consistent around the world. The tonne, litre, and hectare were adopted by the CGPM in 1879 and have been retained as units that may be used alongside SI units, having been given unique symbols. The catalogued units are given below:

Quantity | Name | Symbol | Value in SI Units |

|---|---|---|---|

Time | Minute | min | 1 min = 60s |

Hour | h | 1 h = 60 min = 3600 s | |

Day | d | 1 d = 24 h = 86,400 s | |

Plane Angle | Degree | ° | 1° = (π/180) rad |

Minute | ' | 1′ = (1/60)° = (π/ 10,800) rad | |

Second | " | 1″ = (1/60)′ = (π/ 648,000) rad | |

Area | Hectare | ha | 1 ha = 1 hm2 = 104 m2 |

Volume | Litre | L | 1 L = 1 dm3 = 103 cm3 = 10−3 m3 |

Mass | Metric ton | t | 1 t = 1000 kg |

- Some of the units listed in Table 7 and Table 8 are also accepted for use with the SI.

Non-SI units whose values in SI units must be obtained experimentally (Table 7):

- Physicists often use units of measure that are based on natural phenomena, particularly when the quantities associated with these phenomena are many orders of magnitude greater than or less than the equivalent SI unit. The most common ones have been catalogued in the SI Brochure together with consistent symbols and accepted values, but with the caveat that their values in SI units need to be measured.

electronvolt (symbol eV), and dalton/unified atomic mass unit (Da or u)

- Physicists often use units of measure that are based on natural phenomena, particularly when the quantities associated with these phenomena are many orders of magnitude greater than or less than the equivalent SI unit. The most common ones have been catalogued in the SI Brochure together with consistent symbols and accepted values, but with the caveat that their values in SI units need to be measured.

Sphygmomanometer – the traditional device that measures blood pressure using mercury in a manometer. Pressures are recorded in "millimetres of mercury" – a non-SI unit

Other non-SI units (Table 8):

- A number of non-SI units that had never been formally sanctioned by the CGPM have continued to be used across the globe in many spheres including health care and navigation. As with the units of measure in Tables 6 and 7, these have been catalogued by the CIPM in the SI Brochure to ensure consistent usage, but with the recommendation that authors who use them should define them wherever they are used.

bar, millimetre of mercury, ångström, nautical mile, barn, knot, neper, bel and decibel

- The neper, bel and decibel have been accepted for use with the SI by the CIPM.

- In the interests of standardising health-related units of measure used in the nuclear industry, the 12th CGPM (1964) accepted the continued use of the curie (symbol Ci) as a non-SI unit of activity for radionuclides;[3]:152 the SI derived units becquerel, sievert and gray were adopted in later years. Similarly, the millimetre of mercury (symbol mmHg) was retained for measuring blood pressure.[3]:127

- A number of non-SI units that had never been formally sanctioned by the CGPM have continued to be used across the globe in many spheres including health care and navigation. As with the units of measure in Tables 6 and 7, these have been catalogued by the CIPM in the SI Brochure to ensure consistent usage, but with the recommendation that authors who use them should define them wherever they are used.

Non-SI units associated with the CGS and the CGS-Gaussian system of units (Table 9):

- The SI manual also catalogues a number of legacy units of measure that are used in specific fields such as geodesy and geophysics or are found in the literature, particularly in classical and relativistic electrodynamics where they have certain advantages. The units that are catalogued are:

erg, dyne, poise, stokes, stilb, phot, gal, maxwell, gauss, and oersted.

- The SI manual also catalogues a number of legacy units of measure that are used in specific fields such as geodesy and geophysics or are found in the literature, particularly in classical and relativistic electrodynamics where they have certain advantages. The units that are catalogued are:

Common notions of the metric units

The basic units of the metric system, as originally defined, represented common quantities or relationships in nature. They still do – the modern precisely defined quantities are refinements of definition and methodology, but still with the same magnitudes. In cases where laboratory precision may not be required or available, or where approximations are good enough, the original definitions may suffice.[Note 5]

- A second is 1/60 of a minute, which is 1/60 of an hour, which is 1/24 of a day, so a second is 1/86400 of a day; a second is the time it takes a dense object to freely fall 4.9 metres from rest.

- The metre is close to the length of a pendulum that has a period of 2 seconds; most dining tabletops are about 0.75 metre high; a very tall human (basketball forward) is about 2 metres tall.

- The kilogram is the mass of a litre of cold water; a cubic centimetre or millilitre of water has a mass of one gram; a 1-euro coin, 7.5 g; a Sacagawea US 1-dollar coin, 8.1 g; a UK 50-pence coin, 8.0 g.

- A candela is about the luminous intensity of a moderately bright candle, or 1 candle power; a 60 W tungsten-filament incandescent light bulb has a luminous intensity of about 64 candela.

- A mole of a substance has a mass that is its molecular mass expressed in units of grams; the mass of a mole of table salt is 58.4 g.

- A temperature difference of one kelvin is the same as one degree Celsius: 1/100 of the temperature differential between the freezing and boiling points of water at sea level; the absolute temperature in kelvins is the temperature in degrees Celsius plus about 273; human body temperature is about 37 °C or 310 K.

- A 60 W incandescent light bulb consumes 0.5 amperes at 120 V (US mains voltage) and about 0.26 amperes at 230 V (European mains voltage).

Lexicographic conventions

Unit names

The symbols for the SI units are intended to be identical, regardless of the language used,[3]:130–135 but unit names are ordinary nouns and use the character set and follow the grammatical rules of the language concerned. Names of units follow the grammatical rules associated with common nouns: in English and in French they start with a lowercase letter (e.g., newton, hertz, pascal), even when the symbol for the unit begins with a capital letter. This also applies to "degrees Celsius", since "degree" is the unit.[11][12] The official British and American spellings for certain SI units differ – British English, as well as Australian, Canadian and New Zealand English, uses the spelling deca-, metre, and litre whereas American English uses the spelling deka-, meter, and liter, respectively.[4]:3

Unit symbols and the values of quantities

Although the writing of unit names is language-specific, the writing of unit symbols and the values of quantities is consistent across all languages and therefore the SI Brochure has specific rules in respect of writing them.[3]:130–135 The guideline produced by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)[13] clarifies language-specific areas in respect of American English that were left open by the SI Brochure, but is otherwise identical to the SI Brochure.[14]

General rules

General rules[Note 6] for writing SI units and quantities apply to text that is either handwritten or produced using an automated process:

- The value of a quantity is written as a number followed by a space (representing a multiplication sign) and a unit symbol; e.g., 2.21 kg, 7002730000000000000♠7.3×102 m2, 22 K. This rule explicitly includes the percent sign (%)[3]:134 and the symbol for degrees of temperature (°C).[3]:133 Exceptions are the symbols for plane angular degrees, minutes, and seconds (°, ′, and ″), which are placed immediately after the number with no intervening space.

- Symbols are mathematical entities, not abbreviations, and as such do not have an appended period/full stop (.), unless the rules of grammar demand one for another reason, such as denoting the end of a sentence.

- A prefix is part of the unit, and its symbol is prepended to a unit symbol without a separator (e.g., k in km, M in MPa, G in GHz, μ in μg). Compound prefixes are not allowed. A prefixed unit is atomic in expressions (e.g., km2 is equivalent to (km)2).

- Symbols for derived units formed by multiplication are joined with a centre dot (⋅) or a non-breaking space; e.g., N⋅m or N m.

- Symbols for derived units formed by division are joined with a solidus (/), or given as a negative exponent. E.g., the "metre per second" can be written m/s, m s−1, m⋅s−1, or m/s. A solidus must not be used more than once in a given expression without parentheses to remove ambiguities; e.g., kg/(m⋅s2) and kg⋅m−1⋅s−2 are acceptable, but kg/m/s2 is ambiguous and unacceptable.

Acceleration due to gravity.

The lowercase letters (neither "metres" nor "seconds" were named after people), the space between the value and the units, and the superscript "2" to denote "squared".

- The first letter of symbols for units derived from the name of a person is written in upper case; otherwise, they are written in lower case. E.g., the unit of pressure is named after Blaise Pascal, so its symbol is written "Pa", but the symbol for mole is written "mol". Thus, "T" is the symbol for tesla, a measure of magnetic field strength, and "t" the symbol for tonne, a measure of mass. Since 1979, the litre may exceptionally be written using either an uppercase "L" or a lowercase "l", a decision prompted by the similarity of the lowercase letter "l" to the numeral "1", especially with certain typefaces or English-style handwriting. The American NIST recommends that within the United States "L" be used rather than "l".

- Symbols do not have a plural form, e.g., 25 kg, but not 25 kgs.

- Uppercase and lowercase prefixes are not interchangeable. E.g., the quantities 1 mW and 1 MW represent two different quantities (milliwatt and megawatt).

- The symbol for the decimal marker is either a point or comma on the line. In practice, the decimal point is used in most English-speaking countries and most of Asia, and the comma in most of Latin America and in continental European countries.[15]

- Spaces should be used as a thousands separator (7006100000000000000♠1000000) in contrast to commas or periods (1,000,000 or 1.000.000) to reduce confusion resulting from the variation between these forms in different countries.

- Any line-break inside a number, inside a compound unit, or between number and unit should be avoided. Where this is not possible, line breaks should coincide with thousands separators.

- Because the value of "billion" and "trillion" varies between languages, the dimensionless terms "ppb" (parts per billion) and "ppt" (parts per trillion) should be avoided. The SI Brochure does not suggest alternatives.

Printing SI symbols

The rules covering printing of quantities and units are part of ISO 80000-1:2009.[16]

Further rules[Note 6] are specified in respect of production of text using printing presses, word processors, typewriters and the like.

Examples of the variety of symbols in use around the world for kilometres per hour

Thailand

Germany

Germany

Belgium

United Kingdom

Denmark

France

India

The denominator "hour" (h) is often translated to the country language:

Malaysia

Sweden

Countries with historical ties to the United States often mix up the international "km/h" with the American "MPH":

Philippines

Samoa

International System of Quantities

- SI Brochure

Cover of brochure The International System of Units

The CGPM publishes a brochure that defines and presents the SI.[3] Its official version is in French, in line with the Metre Convention.[3]:102 It leaves some scope for local interpretation, particularly regarding names and terms in different languages.[Note 7][4]

The writing and maintenance of the CGPM brochure is carried out by one of the committees of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM).

The definitions of the terms "quantity", "unit", "dimension" etc. that are used in the SI Brochure are those given in the International vocabulary of metrology.[17]

The quantities and equations that provide the context in which the SI units are defined are now referred to as the International System of Quantities (ISQ).

The system is based on the quantities underlying each of the seven base units of the SI. Other quantities, such as area, pressure, and electrical resistance, are derived from these base quantities by clear non-contradictory equations. The ISQ defines the quantities that are measured with the SI units.[18] The ISQ is defined in the international standard ISO/IEC 80000, and was finalised in 2009 with the publication of ISO 80000-1.[19]

Realisation of units

Silicon sphere for the Avogadro project used for measuring the Avogadro constant to a relative standard uncertainty of 6992200000000000000♠2×10−8 or less, held by Achim Leistner.[20]

Metrologists carefully distinguish between the definition of a unit and its realisation. The definition of each base unit of the SI is drawn up so that it is unique and provides a sound theoretical basis on which the most accurate and reproducible measurements can be made. The realisation of the definition of a unit is the procedure by which the definition may be used to establish the value and associated uncertainty of a quantity of the same kind as the unit. A description of the mise en pratique[Note 8] of the base units is given in an electronic appendix to the SI Brochure.[21][3]:168–169

The published mise en pratique is not the only way in which a base unit can be determined: the SI Brochure states that "any method consistent with the laws of physics could be used to realise any SI unit."[3]:111 In the current (2016) exercise to overhaul the definitions of the base units, various consultative committees of the CIPM have required that more than one mise en pratique shall be developed for determining the value of each unit.[citation needed] In particular:

- At least three separate experiments be carried out yielding values having a relative standard uncertainty in the determination of the kilogram of no more than 6992500000000000000♠5×10−8 and at least one of these values should be better than 6992200000000000000♠2×10−8. Both the Kibble balance and the Avogadro project should be included in the experiments and any differences between these be reconciled.[22][23]

- When the kelvin is being determined, the relative uncertainty of the Boltzmann constant derived from two fundamentally different methods such as acoustic gas thermometry and dielectric constant gas thermometry be better than one part in 6994100000000000000♠10−6 and that these values be corroborated by other measurements.[24]

Evolution of the SI

Changes to the SI

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) has described SI as "the modern metric system".[3]:95 Changing technology has led to an evolution of the definitions and standards that has followed two principal strands – changes to SI itself, and clarification of how to use units of measure that are not part of SI but are still nevertheless used on a worldwide basis.

Since 1960 the CGPM has made a number of changes to the SI to meet the needs of specific fields, notably chemistry and radiometry. These are mostly additions to the list of named derived units, and include the mole (symbol mol) for an amount of substance, the pascal (symbol Pa) for pressure, the siemens (symbol S) for electrical conductance, the becquerel (symbol Bq) for "activity referred to a radionuclide", the gray (symbol Gy) for ionising radiation, the sievert (symbol Sv) as the unit of dose equivalent radiation, and the katal (symbol kat) for catalytic activity.[3]:156[25][3]:156[3]:158[3]:159[3]:165

Acknowledging the advancement of precision science at both large and small scales, the range of defined prefixes pico- (10−12) to tera- (1012) was extended to 10−24 to 1024.[3]:152[3]:158[3]:164

The 1960 definition of the standard metre in terms of wavelengths of a specific emission of the krypton 86 atom was replaced with the distance that light travels in a vacuum in exactly 1/7008299792458000000♠299792458 second, so that the speed of light is now an exactly specified constant of nature.

A few changes to notation conventions have also been made to alleviate lexicographic ambiguities. An analysis under the aegis of CSIRO, published in 2009 by the Royal Society, has pointed out the opportunities to finish the realisation of that goal, to the point of universal zero-ambiguity machine readability.[26]

2019 redefinitions

Dependencies of SI units upon seven physical constants, which are assigned numerical values. Unlike the previous definitions, the base units are all derived exclusively from constants of nature.

After the metre was redefined in 1960, the kilogram remained the only SI base unit directly based on a specific physical artefact, the international prototype of the kilogram (IPK), for its definition and thus the only unit that was still subject to periodic comparisons of national standard kilograms with the IPK.[27] During the 2nd and 3rd Periodic Verification of National Prototypes of the Kilogram, a significant divergence had occurred between the mass of the IPK and all of its official copies stored around the world: the copies had all noticeably increased in mass with respect to the IPK. During extraordinary verifications carried out in 2014 preparatory to redefinition of metric standards, continuing divergence was not confirmed. Nonetheless, the residual and irreducible instability of a physical IPK undermined the reliability of the entire metric system to precision measurement from small (atomic) to large (astrophysical) scales.

A proposal was made that:

- In addition to the speed of light, four constants of nature – the Planck constant, an elementary charge, the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro number – be defined to have exact values

- The International Prototype Kilogram be retired

- The current definitions of the kilogram, ampere, kelvin and mole be revised

- The wording of base unit definitions should change emphasis from explicit unit to explicit constant definitions.

In 2015, the CODATA task group on fundamental constants announced special submission deadlines for data to compute the final values for the new definitions.[28]

The new definitions were adopted at the 26th CGPM in November 2018, and will come into effect in May 2019.[29]

History

Stone marking the Austro-Hungarian/Italian border at Pontebba displaying myriametres, a unit of 10 km used in Central Europe in the 19th century (but since deprecated).[30]

The improvisation of units

The units and unit magnitudes of the metric system which became the SI were improvised piecemeal from everyday physical quantities starting in the mid-18th century. Only later were they moulded into an orthogonal coherent decimal system of measurement.

The degree centigrade as a unit of temperature resulted from the scale devised by Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius in 1742. His scale counter-intuitively designated 100 as the freezing point of water and 0 as the boiling point. Independently, in 1743, the French physicist Jean-Pierre Christin described a scale with 0 as the freezing point of water and 100 the boiling point. The scale became known as the centi-grade, or 100 gradations of temperature, scale.

The metric system was developed from 1791 onwards by a committee of the French Academy of Sciences, commissioned to create a unified and rational system of measures.[31] The group, which included preeminent French men of science,[32]:89 used the same principles for relating length, volume, and mass that had been proposed by the English clergyman John Wilkins in 1668[33][34] and the concept of using the Earth's meridian as the basis of the definition of length, originally proposed in 1670 by the French abbot Mouton.[35][36]

Carl Friedrich Gauss

In March 1791, the Assembly adopted the committee's proposed principles for the new decimal system of measure including the metre defined to be 1/10,000,000th of the length of the quadrant of earth's meridian passing through Paris, and authorised a survey to precisely establish the length of the meridian. In July 1792, the committee proposed the names metre, are, litre and grave for the units of length, area, capacity, and mass, respectively. The committee also proposed that multiples and submultiples of these units were to be denoted by decimal-based prefixes such as centi for a hundredth and kilo for a thousand.[37]:82

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Later, during the process of adoption of the metric system, the Latin gramme and kilogramme, replaced the former provincial terms gravet (1/1000 grave) and grave. In June 1799, based on the results of the meridian survey, the standard mètre des Archives and kilogramme des Archives were deposited in the French National Archives. Subsequently, that year, the metric system was adopted by law in France.[43][44] The French system was short-lived due to its unpopularity. Napoleon ridiculed it, and in 1812, introduced a replacement system, the mesures usuelles or "customary measures" which restored many of the old units, but redefined in terms of the metric system.

During the first half of the 19th century there was little consistency in the choice of preferred multiples of the base units: typically the myriametre (7004100000000000000♠10000 metres) was in widespread use in both France and parts of Germany, while the kilogram (7003100000000000000♠1000 grams) rather than the myriagram was used for mass.[30]

In 1832, the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, assisted by Wilhelm Weber, implicitly defined the second as a base unit when he quoted the Earth's magnetic field in terms of millimetres, grams, and seconds.[38] Prior to this, the strength of the Earth's magnetic field had only been described in relative terms. The technique used by Gauss was to equate the torque induced on a suspended magnet of known mass by the Earth's magnetic field with the torque induced on an equivalent system under gravity. The resultant calculations enabled him to assign dimensions based on mass, length and time to the magnetic field.[Note 9][45]

A candlepower as a unit of illuminance was originally defined by an 1860 English law as the light produced by a pure spermaceti candle weighing 1⁄6 pound (76 grams) and burning at a specified rate. Spermaceti, a waxy substance found in the heads of sperm whales, was once used to make high-quality candles. At this time the French standard of light was based upon the illumination from a Carcel oil lamp. The unit was defined as that illumination emanating from a lamp burning pure rapeseed oil at a defined rate. It was accepted that ten standard candles were about equal to one Carcel lamp.

Metre Convention

| French | English | Pages[3] |

|---|---|---|

| étalons | [Technical] standard | 5, 95 |

| prototype | prototype [kilogram/metre] | 5,95 |

| noms spéciaux | [Some derived units have] special names | 16,106 |

| mise en pratique | mise en pratique [Practical realisation][Note 10] | 82, 171 |

A French-inspired initiative for international cooperation in metrology led to the signing in 1875 of the Metre Convention, also called Treaty of the Metre, by 17 nations.[Note 11][32]:353–354 Initially the convention only covered standards for the metre and the kilogram. In 1921, the Metre Convention was extended to include all physical units, including the ampere and others thereby enabling the CGPM to address inconsistencies in the way that the metric system had been used.[39][3]:96

A set of 30 prototypes of the metre and 40 prototypes of the kilogram,[Note 12] in each case made of a 90% platinum-10% iridium alloy, were manufactured by British metallurgy specialty firm and accepted by the CGPM in 1889. One of each was selected at random to become the International prototype metre and International prototype kilogram that replaced the mètre des Archives and kilogramme des Archives respectively. Each member state was entitled to one of each of the remaining prototypes to serve as the national prototype for that country.[46]

The treaty also established a number of international organisations to oversee the keeping of international standards of measurement:[47][48]

The cgs and MKS systems

Closeup of the National Prototype Metre, serial number 27, allocated to the United States

In the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell, William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) and others working under the auspices of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, built on Gauss' work and formalised the concept of a coherent system of units with base units and derived units christened the centimetre–gram–second system of units in 1874. The principle of coherence was successfully used to define a number of units of measure based on the CGS, including the erg for energy, the dyne for force, the barye for pressure, the poise for dynamic viscosity and the stokes for kinematic viscosity.[41]

In 1879, the CIPM published recommendations for writing the symbols for length, area, volume and mass, but it was outside its domain to publish recommendations for other quantities. Beginning in about 1900, physicists who had been using the symbol "μ" (mu) for "micrometre" or "micron", "λ" (lambda) for "microlitre", and "γ" (gamma) for "microgram" started to use the symbols "μm", "μL" and "μg".[49]

At the close of the 19th century three different systems of units of measure existed for electrical measurements: a CGS-based system for electrostatic units, also known as the Gaussian or ESU system, a CGS-based system for electromechanical units (EMU) and an International system based on units defined by the Metre Convention.[50] for electrical distribution systems.

Attempts to resolve the electrical units in terms of length, mass, and time using dimensional analysis was beset with difficulties—the dimensions depended on whether one used the ESU or EMU systems.[42] This anomaly was resolved in 1901 when Giovanni Giorgi published a paper in which he advocated using a fourth base unit alongside the existing three base units. The fourth unit could be chosen to be electric current, voltage, or electrical resistance.[51] Electric current with named unit 'ampere' was chosen as the base unit, and the other electrical quantities derived from it according to the laws of physics. This became the foundation of the MKS system of units.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a number of non-coherent units of measure based on the gram/kilogram, centimetre/metre and second, such as the Pferdestärke (metric horsepower) for power,[52][Note 13] the darcy for permeability[53] and "millimetres of mercury" for barometric and blood pressure were developed or propagated, some of which incorporated standard gravity in their definitions.[Note 14]

At the end of the Second World War, a number of different systems of measurement were in use throughout the world. Some of these systems were metric system variations; others were based on customary systems of measure, like the U.S customary system and Imperial system of the UK and British Empire.

The Practical system of units

In 1948, the 9th CGPM commissioned a study to assess the measurement needs of the scientific, technical, and educational communities and "to make recommendations for a single practical system of units of measurement, suitable for adoption by all countries adhering to the Metre Convention".[54] This working document was Practical system of units of measurement. Based on this study, the 10th CGPM in 1954 defined an international system derived from six base units including units of temperature and optical radiation in addition to those for the MKS system mass, length, and time units and Giorgi's current unit. Six base units were recommended: the metre, kilogram, second, ampere, degree Kelvin, and candela.

The 9th CGPM also approved the first formal recommendation for the writing of symbols in the metric system when the basis of the rules as they are now known was laid down.[55] These rules were subsequently extended and now cover unit symbols and names, prefix symbols and names, how quantity symbols should be written and used and how the values of quantities should be expressed.[3]:104,130

Birth of the SI

Countries which have officially adopted the metric system (green)

In 1960, the 11th CGPM synthesised the results of the 12-year study into a set of 16 resolutions. The system was named the International System of Units, abbreviated SI from the French name, Le Système International d'Unités.[3]:110[56]

See also

- Introduction to the metric system

- Outline of the metric system

- List of international common standards

- Metre–tonne–second system of units

Organisations

- Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements

Standards and conventions

- Conventional electrical unit

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) – Primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time- Unified Code for Units of Measure

Notes

^ For historical reasons, the kilogram rather than the gram is treated as the coherent unit, making an exception to this characterisation.

^ Ohm's law: 1 Ω = 1 V/A from the relationship E = I × R, where E is electromotive force or voltage (unit: volt), I is current (unit: ampere), and R is resistance (unit: ohm).

^ This object is the International Prototype Kilogram or IPK called rather poetically Le Grand K.

^ This grouping reflects the 2014 revision of the 8th Edition of the SI Brochure (2006).

^ While the second is readily determined from the Earth's rotation period, the metre, originally defined in terms of the Earth's size and shape, is less amenable; however, that the Earth's circumference is very close to 40,000 km may be a useful mnemonic.

^ ab Except where specifically noted, these rules are common to both the SI Brochure and the NIST brochure.

^ For example, the United States' National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has produced a version of the CGPM document (NIST SP 330) which clarifies local interpretation for English-language publications that use American English

^ This term is a translation of the official [French] text of the SI Brochure.

^ The strength of the earth's magnetic field was designated 1 G (gauss) at the surface (= 1 cm−1/2⋅g1/2⋅s−1).

^ The 8th edition of the SI Brochure (2008) notes that [at that time of publication] the term "mise en pratique" had not been fully defined.

^ Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Italy, Peru, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden and Norway, Switzerland, Ottoman Empire, United States and Venezuela.

^ The text "Des comparaisons périodiques des étalons nationaux avec les prototypes internationaux" (English: the periodic comparisons of national standards with the international prototypes) in article 6.3 of the Metre Convention distinguishes between the words "standard" (OED: "The legal magnitude of a unit of measure or weight") and "prototype" (OED: "an original on which something is modelled").

^ Pferd is German for "horse" and Stärke is German for "strength" or "power". The Pferdestärke is the power needed to raise 75 kg against gravity at the rate of one metre per second. (1 PS = 0.985 HP).

^ This constant is unreliable, because it varies over the surface of the earth.

References

^ ab Materese, Robin (2018-11-16). "Historic Vote Ties Kilogram and Other Units to Natural Constants". NIST. Retrieved 2018-11-16..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "The World Factbook Appendix G". CIA. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaab International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

^ abcdefg Taylor, Barry N.; Thompson, Ambler (2008). The International System of Units (SI) (Special publication 330) (PDF). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

^

Quantities Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, IUPAC

^ Page, Chester H.; Vigoureux, Paul, eds. (1975-05-20). The International Bureau of Weights and Measures 1875–1975: NBS Special Publication 420. Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. pp. 238–244.

^ Secula, Erik M. (7 October 2014). "Redefining the Kilogram, The Past". Nist.gov. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

^ McKenzie, A. E. E. (1961). Magnetism and Electricity. Cambridge University Press. p. 322.

^ "Units & Symbols for Electrical & Electronic Engineers". Institution of Engineering and Technology. 1996. pp. 8–11. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

^ ab Thompson, Ambler; Taylor, Barry N. (2008). Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) (Special publication 811) (PDF). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

^ Rowlett, Russ (2004-07-14). "Using Abbreviations or Symbols". University of North Carolina. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

^ "SI Conventions". National Physical Laboratory. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

^

Thompson, A.; Taylor, B. N. (July 2008). "NIST Guide to SI Units – Rules and Style Conventions". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

^ "Interpretation of the International System of Units (the Metric System of Measurement) for the United States" (PDF). Federal Register. 73 (96): 28432–28433. 2008-05-09. FR Doc number E8-11058. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

^ Williamson, Amelia A. (March–April 2008). "Period or Comma? Decimal Styles over Time and Place" (PDF). Science Editor. 31 (2): 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

^ "ISO 80000-1:2009(en) Quantities and Units—Past 1:General". International Organization for Standardization. 2009. Retrieved 2013-08-22.

^ "The International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM)".

^ "1.16" (PDF). International vocabulary of metrology – Basic and general concepts and associated terms (VIM) (3rd ed.). International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM): Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology. 2012. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

^ S. V. Gupta, Units of Measurement: Past, Present and Future. International System of Units, p. 16, Springer, 2009.

ISBN 3642007384.

^ "Avogadro Project". National Physical Laboratory. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

^ "What is a mise en pratique?". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

^ "Recommendations of the Consultative Committee for Mass and Related Quantities to the International Committee for Weights and Measures" (PDF). 12th Meeting of the CCM. Sèvres: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

^ "Recommendations of the Consultative Committee for Amount of Substance – Metrology in Chemistry to the International Committee for Weights and Measures" (PDF). 16th Meeting of the CCQM. Sèvres: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 15–16 April 2010. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

^ "Recommendations of the Consultative Committee for Thermometry to the International Committee for Weights and Measures" (PDF). 25th Meeting of the CCT. Sèvres: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 6–7 May 2010. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

^ p. 221 – McGreevy

^ Foster, Marcus P. (2009), "Disambiguating the SI notation would guarantee its correct parsing" (PDF), Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 465 (2104): 1227–1229, doi:10.1098/rspa.2008.0343.

^ "Redefining the kilogram". UK National Physical Laboratory. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

^ Mohr, Peter J.; Newell, David B.; Taylor, Barry N. (2015). "CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2014 – Summary". Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.22827.Because of the good progress made in both experiment and theory since the 31 December 2010 closing date of the 2010 CODATA adjustment, the uncertainties of the 2014 recommended values of h, e, k and NA are already at the level required for the adoption of the revised SI by the 26th CGPM in the fall of 2018. The formal road map to redefinition includes a special CODATA adjustment of the fundamental constants with a closing date for new data of 1 July 2017 in order to determine the exact numerical values of h, e, k and NA that will be used to define the New SI. A second CODATA adjustment with a closing date of 1 July 2018 will be carried out so that a complete set of recommended values consistent with the New SI will be available when it is formally adopted by the 26th CGPM.

^ Wood, B. (3–4 November 2014). "Report on the Meeting of the CODATA Task Group on Fundamental Constants" (PDF). BIPM. p. 7.[BIPM director Martin] Milton responded to a question about what would happen if ... the CIPM or the CGPM voted not to move forward with the redefinition of the SI. He responded that he felt that by that time the decision to move forward should be seen as a foregone conclusion.

^ ab "Amtliche Maßeinheiten in Europa 1842" [Official units of measure in Europe 1842] (in German). Retrieved 2011-03-26 Text version of Malaisé's book:

Malaisé, Ferdinand von (1842). Theoretisch-practischer Unterricht im Rechnen [Theoretical and practical instruction in arithmetic] (in German). München. pp. 307–322. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

^ "The name 'kilogram'". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2006.

^ ab Alder, Ken (2002). The Measure of all Things—The Seven-Year-Odyssey that Transformed the World. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11507-8.

^ Quinn, Terry (2012). From artefacts to atoms: the BIPM and the search for ultimate measurement standards. Oxford University Press. p. xxvii. ISBN 978-0-19-530786-3.he [Wilkins] proposed essentially what became ... the French decimal metric system

^ Wilkins, John (1668). "VII". An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language. The Royal Society. pp. 190–194.

"Reproduction (33 MB)" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-03-06.; "Transcription" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-03-06.

^ "Mouton, Gabriel". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. encyclopedia.com. 2008. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (January 2004), "Gabriel Mouton", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

^ Tavernor, Robert (2007). Smoot's Ear: The Measure of Humanity. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12492-7.

^ ab "Brief history of the SI". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

^ ab Tunbridge, Paul (1992). Lord Kelvin, His Influence on Electrical Measurements and Units. Peter Pereginus Ltd. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-0-86341-237-0.

^ Everett, ed. (1874). "First Report of the Committee for the Selection and Nomenclature of Dynamical and Electrical Units". Report on the Forty-third Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science Held at Bradford in September 1873: 222–225. Retrieved 2013-08-28.Special names, if short and suitable, would ... be better than the provisional designation 'C.G.S. unit of ...'.

^ ab Page, Chester H.; Vigoureux, Paul, eds. (1975-05-20). The International Bureau of Weights and Measures 1875–1975: NBS Special Publication 420. Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. p. 12.

^ ab Maxwell, J. C. (1873). A treatise on electricity and magnetism. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 242–245. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

^ Bigourdan, Guillaume (2012) [1901]. Le Système Métrique Des Poids Et Mesures: Son Établissement Et Sa Propagation Graduelle, Avec L'histoire Des Opérations Qui Ont Servi À Déterminer Le Mètre Et Le Kilogramme (facsimile edition) [The Metric System of Weights and Measures: Its Establishment and its Successive Introduction, with the History of the Operations Used to Determine the Metre and the Kilogram] (in French). Ulan Press. p. 176. ASIN B009JT8UZU.

^ Smeaton, William A. (2000). "The Foundation of the Metric System in France in the 1790s: The importance of Etienne Lenoir's platinum measuring instruments". Platinum Metals Rev. 44 (3): 125–134. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

^ "The intensity of the Earth's magnetic force reduced to absolute measurement" (PDF).

^ Nelson, Robert A. (1981). "Foundations of the international system of units (SI)" (PDF). Physics Teacher: 597.

^ "The Metre Convention". Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

^

General Conference on Weights and Measures (Conférence générale des poids et mesures or CGPM)

International Committee for Weights and Measures (Comité international des poids et mesures or CIPM)

International Bureau of Weights and Measures (Bureau international des poids et mesures or BIPM) – an international metrology centre at Sèvres in France that has custody of the International prototype kilogram, provides metrology services for the CGPM and CIPM,

^ McGreevy, Thomas (1997). Cunningham, Peter, ed. The Basis of Measurement: Volume 2 – Metrication and Current Practice. Pitcon Publishing (Chippenham) Ltd. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0-948251-84-9.

^ Fenna, Donald (2002). Weights, Measures and Units. Oxford University Press. International unit. ISBN 978-0-19-860522-5.

^ "Historical figures: Giovanni Giorgi". International Electrotechnical Commission. 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

^ "Die gesetzlichen Einheiten in Deutschland" [List of units of measure in Germany] (PDF) (in German). Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB). p. 6. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

^ "Porous materials: Permeability" (PDF). Module Descriptor, Material Science, Materials 3. Materials Science and Engineering, Division of Engineering, The University of Edinburgh. 2001. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

^ "BIPM - Resolution 6 of the 9th CGPM". Bipm.org. 1948. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

^ "Resolution 7 of the 9th meeting of the CGPM (1948): Writing and printing of unit symbols and of numbers". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

^ "BIPM - Resolution 12 of the 11th CGPM". Bipm.org. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

Further reading

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science.

ISBN 0-632-03583-8. Electronic version.

- Unit Systems in Electromagnetism

MW Keller et al. Metrology Triangle Using a Watt Balance, a Calculable Capacitor, and a Single-Electron Tunneling Device

"The Current SI Seen From the Perspective of the Proposed New SI". Barry N. Taylor. Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Vol. 116, No. 6, Pgs. 797–807, Nov–Dec 2011.- B. N. Taylor, Ambler Thompson, International System of Units (SI), National Institute of Standards and Technology 2008 edition,

ISBN 1437915582.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to International System of Units. |

- Official

BIPM – About the BIPM (home page)

- BIPM – measurement units

BIPM brochure (SI reference)

- ISO 80000-1:2009 Quantities and units – Part 1: General

NIST On-line official publications on the SI

- NIST Special Publication 330, 2008 Edition: The International System of Units (SI)

- NIST Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition: Guide for the Use of the International System of Units

- NIST Special Pub 814: Interpretation of the SI for the United States and Federal Government Metric Conversion Policy

- Rules for SAE Use of SI (Metric) Units

International System of Units at Curlie

EngNet Metric Conversion Chart Online Categorised Metric Conversion Calculator- U.S. Metric Association. 2008. A Practical Guide to the International System of Units

- History

LaTeX SIunits package manual gives a historical background to the SI system.

- Research

- The metrological triangle

- Recommendation of ICWM 1 (CI-2005)