Mandelstam variables

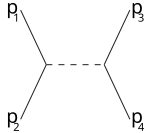

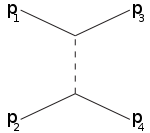

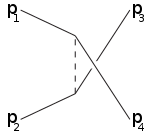

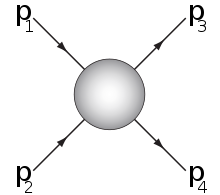

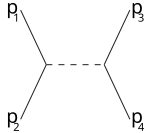

In this diagram, two particles come in with momenta p1 and p2, they interact in some fashion, and then two particles with different momentum (p3 and p4) leave.

In theoretical physics, the Mandelstam variables are numerical quantities that encode the energy, momentum, and angles of particles in a scattering process in a Lorentz-invariant fashion. They are used for scattering processes of two particles to two particles. The Mandelstam variables were first introduced by physicist Stanley Mandelstam in 1958.

If the Minkowski Metric is chosen to be diag(1,−1,−1,−1){displaystyle mathrm {diag} (1,-1,-1,-1)}

- s=(p1+p2)2=(p3+p4)2{displaystyle s=(p_{1}+p_{2})^{2}=(p_{3}+p_{4})^{2},}

- t=(p1−p3)2=(p4−p2)2{displaystyle t=(p_{1}-p_{3})^{2}=(p_{4}-p_{2})^{2},}

- u=(p1−p4)2=(p3−p2)2{displaystyle u=(p_{1}-p_{4})^{2}=(p_{3}-p_{2})^{2},}

- s=(p1+p2)2=(p3+p4)2{displaystyle s=(p_{1}+p_{2})^{2}=(p_{3}+p_{4})^{2},}

Where p1 and p2 are the four-momenta of the incoming particles and p3 and p4 are the four-momenta of the outgoing particles, and we are using relativistic units (c=1).

s is also known as the square of the center-of-mass energy (invariant mass) and t is also known as the square of the four-momentum transfer.

Contents

1 Feynman diagrams

2 Details

2.1 Relativistic limit

2.2 Sum

2.2.1 Proof

3 See also

4 References

Feynman diagrams

The letters s,t,u{displaystyle s,t,u}

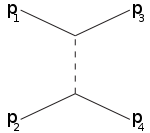

s-channel

t-channel

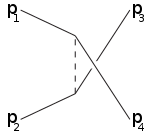

u-channel

For example, the s-channel corresponds to the particles 1,2 joining into an intermediate particle that eventually splits into 3,4: the s-channel is the only way that resonances and new unstable particles may be discovered provided their lifetimes are long enough that they are directly detectable. The t-channel represents the process in which the particle 1 emits the intermediate particle and becomes the final particle 3, while the particle 2 absorbs the intermediate particle and becomes 4. The u-channel is the t-channel with the role of the particles 3,4 interchanged.

Details

Relativistic limit

In the relativistic limit, the momentum (speed) is large, so using the relativistic energy-momentum equation, the energy becomes essentially the momentum norm (e.g. E2=p⋅p+m02{displaystyle E^{2}=mathbf {p} cdot mathbf {p} +{m_{0}}^{2}}

So for example,

- s=(p1+p2)2=p12+p22+2p1⋅p2≈2p1⋅p2{displaystyle s=(p_{1}+p_{2})^{2}=p_{1}^{2}+p_{2}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2}approx 2p_{1}cdot p_{2},}

- s=(p1+p2)2=p12+p22+2p1⋅p2≈2p1⋅p2{displaystyle s=(p_{1}+p_{2})^{2}=p_{1}^{2}+p_{2}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2}approx 2p_{1}cdot p_{2},}

because p12=m12{displaystyle p_{1}^{2}=m_{1}^{2}}

Thus,

s≈{displaystyle sapprox ,}

2p1⋅p2≈{displaystyle 2p_{1}cdot p_{2}approx ,}

2p3⋅p4{displaystyle 2p_{3}cdot p_{4},}

t≈{displaystyle tapprox ,}

−2p1⋅p3≈{displaystyle -2p_{1}cdot p_{3}approx ,}

−2p2⋅p4{displaystyle -2p_{2}cdot p_{4},}

u≈{displaystyle uapprox ,}

−2p1⋅p4≈{displaystyle -2p_{1}cdot p_{4}approx ,}

−2p3⋅p2{displaystyle -2p_{3}cdot p_{2},}

Sum

Note that

- s+t+u=m12+m22+m32+m42{displaystyle s+t+u=m_{1}^{2}+m_{2}^{2}+m_{3}^{2}+m_{4}^{2},}

where mi{displaystyle m_{i}}

Proof

To prove this, we need to use two facts:

- The square of a particle's four momentum is the square of its mass,

- pi2=mi2(1){displaystyle p_{i}^{2}=m_{i}^{2}quad quad quad quad quad quad quad quad quad quad quad (1),}

- And conservation of four-momentum,

- p1+p2=p3+p4{displaystyle p_{1}+p_{2}=p_{3}+p_{4},}

- p1=−p2+p3+p4(2){displaystyle p_{1}=-p_{2}+p_{3}+p_{4}quad quad quad quad quad quad quad (2),}

So, to begin,

- s=(p1+p2)2=p12+p22+2p1⋅p2{displaystyle s=(p_{1}+p_{2})^{2}=p_{1}^{2}+p_{2}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2},}

- t=(p1−p3)2=p12+p32−2p1⋅p3{displaystyle t=(p_{1}-p_{3})^{2}=p_{1}^{2}+p_{3}^{2}-2p_{1}cdot p_{3},}

- u=(p1−p4)2=p12+p42−2p1⋅p4{displaystyle u=(p_{1}-p_{4})^{2}=p_{1}^{2}+p_{4}^{2}-2p_{1}cdot p_{4},}

- s=(p1+p2)2=p12+p22+2p1⋅p2{displaystyle s=(p_{1}+p_{2})^{2}=p_{1}^{2}+p_{2}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2},}

Then adding the three while inserting squared masses leads to,

- s+t+u=m12+m22+m32+m42+2p12+2p1⋅p2−2p1⋅p3−2p1⋅p4{displaystyle s+t+u=m_{1}^{2}+m_{2}^{2}+m_{3}^{2}+m_{4}^{2}+2p_{1}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2}-2p_{1}cdot p_{3}-2p_{1}cdot p_{4},}

- s+t+u=m12+m22+m32+m42+2p12+2p1⋅p2−2p1⋅p3−2p1⋅p4{displaystyle s+t+u=m_{1}^{2}+m_{2}^{2}+m_{3}^{2}+m_{4}^{2}+2p_{1}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2}-2p_{1}cdot p_{3}-2p_{1}cdot p_{4},}

Then note that the last four terms add up to zero using conservation of four-momentum,

- 2p12+2p1⋅p2−2p1⋅p3−2p1⋅p4=2p1⋅(p1+p2−p3−p4)=0{displaystyle 2p_{1}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2}-2p_{1}cdot p_{3}-2p_{1}cdot p_{4}=2p_{1}cdot (p_{1}+p_{2}-p_{3}-p_{4})=0,}

- 2p12+2p1⋅p2−2p1⋅p3−2p1⋅p4=2p1⋅(p1+p2−p3−p4)=0{displaystyle 2p_{1}^{2}+2p_{1}cdot p_{2}-2p_{1}cdot p_{3}-2p_{1}cdot p_{4}=2p_{1}cdot (p_{1}+p_{2}-p_{3}-p_{4})=0,}

So finally,

s+t+u=m12+m22+m32+m42{displaystyle s+t+u=m_{1}^{2}+m_{2}^{2}+m_{3}^{2}+m_{4}^{2},}

See also

- Feynman diagrams

- Bhabha scattering

- Møller scattering

- Compton scattering

References

Mandelstam, S. (1958). "Determination of the Pion-Nucleon Scattering Amplitude from Dispersion Relations and Unitarity". Physical Review. 112 (4): 1344. Bibcode:1958PhRv..112.1344M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.112.1344. Archived from the original on 2000-05-28..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Halzen, Francis; Martin, Alan (1984). Quarks & Leptons: An Introductory Course in Modern Particle Physics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-88741-2.

Perkins, Donald H. (2000). Introduction to High Energy Physics (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62196-8.