History of art

The Creation of Adam; by Michelangelo; 1508–1512; fresco; 480.1 × 230.1 cm (15.7 × 7.5 ft); Sistine Chapel (Vatican City)

| European art history |

|---|

|

|

History of art |

|

Art history |

The history of art focuses on objects made by humans in visual form for aesthetic purposes. Visual art can be classified in diverse ways, such as separating fine arts from applied arts; inclusively focusing on human creativity; or focusing on different media such as architecture, sculpture, painting, film, photography, and graphic arts. In recent years, technological advances have led to video art, computer art, Performance art, animation, television, and videogames.

The history of art is often told as a chronology of masterpieces created during each civilization. It can thus be framed as a story of high culture, epitomized by the Wonders of the World. On the other hand, vernacular art expressions can also be integrated into art historical narratives, referred to as folk arts or craft. The more closely that an art historian engages with these latter forms of low culture, the more likely it is that they will identify their work as examining visual culture or material culture, or as contributing to fields related to art history, such as anthropology or archaeology. In the latter cases art objects may be referred to as archeological artifacts.

Contents

1 Prehistory

1.1 Paleolithic

1.2 Mesolithic

1.3 Neolithic

1.4 Metal Age

2 Ancient art

2.1 Ancient Near East

2.2 Egypt

2.3 Indus Valley Civilisation/Harappan

2.4 Ancient China

2.5 Greek

2.6 Phoenician

2.7 Etruscan

2.8 Dacian

2.9 Pre-Roman Iberian

2.10 Hittite

2.11 Bactrian

2.12 Celtic

2.13 Achaemenid

2.14 Rome

2.15 Olmec

2.16 Dong Son

2.17 Old Bering Sea

3 European

3.1 Medieval

3.1.1 Byzantine

3.1.2 Anglo-Saxon

3.1.3 Ottonian

3.1.4 Viking art

3.1.5 Romanesque

3.1.6 Slavic

3.2 Renaissance

3.3 Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassicism

3.4 Romanticism and realism

4 Middle Eastern

4.1 Pre-Islamic Arabia

4.2 Islamic

5 Siberian-Eskimo

6 Americas

6.1 Preclassic

6.2 Classic

6.3 Postclassic

6.4 Art in the Americas

6.5 Aztec

6.6 Mayan

6.7 Costa Rica and Panama

6.8 Colombia

6.9 Andean regions

6.10 Amazonia and the Caraibbes

6.11 United States and Canada

6.12 Inuit

7 Asian art

7.1 Central Asia

7.2 Indian

7.3 Nepalese, Bhutanese, and Tibetan

7.4 Chinese

7.5 Japanese

7.6 Korean

7.7 Vietnamese

7.8 Thai

7.9 Cambodian/Khmer

7.10 Indonesian

8 Africa

9 Oceania

10 Modern and contemporary

10.1 Origins

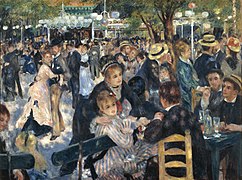

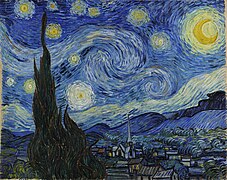

10.2 19th century

10.3 Early 20th century

10.4 Late 20th and early 21st centuries

11 See also

12 References

13 Further reading

14 External links

14.1 Timelines

Prehistory

Aurochs on a cave painting in Lascaux (France)

Venus of Willendorf; c. 25,000 BCE (the Gravettian period); limestone with ocre coloring; height: 11 cm (41⁄4 in.); Naturhistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)

The oldest human art that has been found dates to the Stone Age, when the first creative works were made from shell, stone, and paint. During the Paleolithic (25,000–8,000 BCE), humans practiced hunting and gathering and lived in caves, where cave painting was developed.[1] During the Neolithic period (6000–3000 BCE), the production of handicrafts commenced.

The earliest human artifacts showing evidence of workmanship with an artistic purpose are the subject of some debate. It is clear that such workmanship existed by 40,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic era, although it is quite possible that it began earlier. Engraved shells created by homo erectus dating as far back as 500,000 years ago have been found, although experts disagree on whether these engravings can be properly classified as ‘art’.[2]

Paleolithic

Bison Licking Insect Bite; 15,000–13,000 BCE; antler; National Museum of Prehistory (Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil, France)

The Paleolithic had its first artistic manifestation in 25,000 BCE, reaching its peak in the Magdalenian period (±15,000–8,000 BCE). Surviving art from this period includes small carvings in stone or bone and cave painting. The first traces of human-made objects appeared in southern Africa, the Western Mediterranean, Central and Eastern Europe (Adriatic Sea), Siberia (Baikal Lake), India and Australia. These first traces are generally worked stone (flint, obsidian), wood or bone tools. To paint in red, iron oxide was used. Cave paintings have been found in the Franco-Cantabrian region. There are pictures that are abstract as well as pictures that are naturalistic. Animals were painted in the caves of Altamira, Trois Frères, Chauvet and Lascaux. Sculpture is represented by the so-called Venus figurines, feminine figures which may have been used in fertility cults, such as the Venus of Willendorf.[3] There is a theory that these figures may have been made by women as expressions of their own body.[4] Other representative works of this period are the Man from Brno[5] and the Venus of Brassempouy.[6]

Mesolithic

In Old World archaeology, Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, mesos "middle"; λίθος, lithos "stone") is the period between

the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus.

The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia.

It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and West Asia, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. In Europe it spans roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BP, in Southwest Asia (the Epipalaeolithic Near East) roughly 20,000 to 8,000 BP.

The term is less used of areas further east, and not all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

Neolithic

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:left;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:center}}

The Thinker; c. 5000 BCE; terracotta; height: 11.5 cm (41⁄2 in.); by Hamangia culture from Romania

The Sitting Woman; c. 5000 BCE; terracotta; height: 11.4 cm (41⁄2 in.); the Hamangia culture from Romania

The Neolithic period began in about 8,000 BCE. The rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin—dated between the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras—contained small, schematic paintings of human figures, with notable examples in El Cogul, Valltorta, Alpera and Minateda.

Neolithic painting is similar to paintings found in northern Africa (Atlas, Sahara) and in the area of modern Zimbabwe. Neolithic painting is often schematic, made with basic strokes (men in the form of a cross and women in a triangular shape). There are also cave paintings in Pinturas River in Argentina, especially the Cueva de las Manos. In portable art, a style called Cardium Pottery was produced, decorated with imprints of seashells. New materials were used in art, such as amber, crystal, and jasper. In this period, the first traces of urban planning appeared, such as the remains in Tell as-Sultan (Jericho), Jarmo (Iraq) and Çatalhöyük (Anatolia).[7] In South-Eastern Europe appeared many cultures, such as the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture (from Romania, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine), and the Hamangia culture (from Romania and Bulgaria). Another region with many cultures is China most notable being the Yangshao culture and the Longshan culture.

Metal Age

Trundholm sun chariot; c. 1400 BCE; bronze; height: 35 cm (14 in.), width: 54 cm (21 in.); National Museum of Denmark (Copenhagen)

The last prehistoric phase is the Metal Age (or Three-age system), during which the use of copper, bronze and iron transformed ancient societies. When humans could smelt metal and forge metal implements could make new tools, weapons, and art.

In the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) megaliths emerged. Examples include the dolmen and menhir and the English cromlech, as can be seen in the complexes at Newgrange and Stonehenge.[8] In Spain the Los Millares culture was formed which was characterized by the Beaker culture. In Malta, the temple complexes of Ħaġar Qim, Mnajdra, Tarxien and Ġgantija were built. In the Balearic Islands notable megalithic cultures developed, with different types of monuments: the naveta, a tomb shaped like a truncated pyramid, with an elongated burial chamber; the taula, two large stones, one put vertically and the other horizontally above each other; and the talaiot, a tower with a covered chamber and a false dome.[9]

In the Iron Age the cultures of Hallstatt (Austria) and La Tene (Switzerland) emerged in Europe. The first was developed between the 7th and 5th century BCE by the necropoleis with tumular tombs and a wooden burial chamber in the form of a house, often accompanied by a four-wheeled cart. The pottery was polychromic, with geometric decorations and applications of metallic ornaments. La Tene was developed between the 5th and 4th century BCE, and is more popularly known as early Celtic art. It produced many iron objects such as swords and spears, which have not survived well to the 2000s due to rust.

The Bronze Age refers to the period when bronze was the best material available. Bronze was used for highly decorated shields, fibulas, and other objects, with different stages of evolution of the style. Decoration was influenced by Greek, Etruscan and Scythian art.[10]

Ancient art

Statue of Gudea I, patesi of Lagash; 2120 BCE; Louvre (Paris)

In the first period of recorded history, art coincided with writing. The great civilizations of the Near East: Egypt and Mesopotamia arose. Globally, during this period the first great cities appeared near major rivers: the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, Indus and Yellow Rivers.

One of the great advances of this period was writing, which was developed from the tradition of communication using pictures. The first form of writing were the Jiahu symbols from neolithic China, but the first true writing was cuneiform script, which emerged in Mesopotamia c. 3500 BCE, written on clay tablets. It was based on pictographic and ideographic elements, while later Sumerians developed syllables for writing, reflecting the phonology and syntax of the Sumerian language. In Egypt hieroglyphic writing was developed using pictures as well, appearing on art such as the Narmer Palette (3,100 BCE). The Indus Valley Civilization sculpted seals with short texts and decorated with representations of animals and people. Meanwhile, the Olmecs sculpted colossal heads and decorated other sculptures with their own hierglyphs. In these times, writing was accessible only for the elites.

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamian art was developed in the area between Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in modern-day Syria and Iraq, where since the 4th millennium BCE many different cultures existed such as Sumer, Akkad, Amorite and Chaldea. Mesopotamian architecture was characterized by the use of bricks, lintels, and cone mosaic. Notable are the ziggurats, large temples in the form of step pyramids. The tomb was a chamber covered with a false dome, as in some examples found at Ur. There were also palaces walled with a terrace in the form of a ziggurat, where gardens were an important feature. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Relief sculpture was developed in wood and stone. Sculpture depicted religious, military, and hunting scenes, including both human and animal figures. In the Sumerian period, small statues of people were produced. These statues had an angular form and were produced from colored stone. The figures typically had bald head with hands folded on the chest. In the Akkadian period, statues depicted figures with long hair and beards, such as the stele of Naram-Sin. In the Amorite period (or Neosumerian), statues represented kings from Gudea of Lagash, with their mantle and a turban on their heads and their hands on their chests. During Babylonian rule, the stele of Hammurabi was important, as it depicted the great king Hammurabi above a written copy of the laws that he introduced. Assyrian sculpture is notable for its anthropomorphism of cattle and the winged genie, which is depicted flying in many reliefs depicting war and hunting scenes, such as in the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.[11]

Egypt

One of the first great civilizations arose in Egypt, which had elaborate and complex works of art produced by professional artists and craftspeople. Egypt's art was religious and symbolic. Given that the culture had a highly centralized power structure and hierarchy, a great deal of art was created to honour the pharaoh, including great monuments. Egyptian art and culture emphasized the religious concept of immortality. Later Egyptian art includes Coptic and Byzantine art.

The architecture is characterized by monumental structures, built with large stone blocks, lintels, and solid columns. Funerary monuments included mastaba, tombs of rectangular form; pyramids, which included step pyramids (Saqqarah) or smooth-sided pyramids (Giza); and the hypogeum, underground tombs (Valley of the Kings). Other great buildings were the temple, which tended to be monumental complexes preceded by an avenue of sphinxes and obelisks. Temples used pylons and trapezoid walls with hypaethros and hypostyle halls and shrines. The temples of Karnak, Luxor, Philae and Edfu are good examples. Another type of temple is the rock temple, in the form of a hypogeum, found in Abu Simbel and Deir el-Bahari.

Painting of the Egyptian era used a juxtaposition of overlapping planes. The images were represented hierarchically, i.e., the Pharaoh is larger than the common subjects or enemies depicted at his side. Egyptians painted the outline of the head and limbs in profile, while the torso, hands, and eyes were painted from the front. Applied arts were developed in Egypt, in particular woodwork and metalwork. There are superb examples such as cedar furniture inlaid with ebony and ivory which can be seen in the tombs at the Egyptian Museum. Other examples include the pieces found in Tutankhamun's tomb, which are of great artistic value.[12]

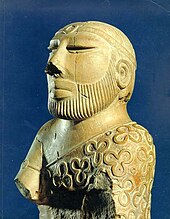

Indus Valley Civilisation/Harappan

Discovered long after the contemporary civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization or Harappan civilization (c. 2400–1900 BCE) is now recognized as extraordinally advanced, comparable in many ways with those cultures.

Various sculptures, seals, bronze vessels pottery, gold jewellery, and anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze, and steatite have been found at excavation sites.[13]

A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form. These terracotta figurines included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. The animal depicted on a majority of seals at sites of the mature period has not been clearly identified. Part bull, part zebra, with a majestic horn, it has been a source of speculation. As yet, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate claims that the image had religious or cultic significance, but the prevalence of the image raises the question of whether or not the animals in images of the IVC are religious symbols.[14]

Sir John Marshall reacted with surprise when he saw the famous Indus bronze statuette of a slender-limbed dancing girl in Mohenjo-daro:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

When I first saw them I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art, and culture. Modeling such as this was unknown in the ancient world up to the Hellenistic age of Greece, and I thought, therefore, that some mistake must surely have been made; that these figures had found their way into levels some 3000 years older than those to which they properly belonged .... Now, in these statuettes, it is just this anatomical truth which is so startling; that makes us wonder whether, in this all-important matter, Greek artistry could possibly have been anticipated by the sculptors of a far-off age on the banks of the Indus.[15]

Seals have been found at Mohenjo-daro depicting a figure standing on its head, and another sitting cross-legged in what some call a yoga-like pose (see image, the so-called Pashupati, below).[citation needed] This figure, sometimes known as a Pashupati, has been variously identified. Sir John Marshall identified a resemblance to the Hindu god, Shiva.[16] If this can be validated, it would be evidence that some aspects of Hinduism predate the earliest texts, the Veda.[citation needed]

Ancient China

Houmuwu ding, the largest ancient bronze ever found; 1300–1046 BCE; bronze; National Museum of China (Beijing)

During the Chinese Bronze Age (the Shang and Zhou dynasties) court intercessions and comunication with the spirit world were conducted by a shaman (possibly the king himself). In the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BCE), the supreme deity was Shangdi, but aristicratic families preferred to contact the spirits of their ancestors. They prepared elaborate banquets of food and drink for them, heated and served in bronze ritual vessels. Bronze vessels were used in religious rituals to cement Dhang authority, and when the Shang capital fell, around 1050 BCE, its conquerors, the Zhou (c. 1050–156 BCE), continued to use these containers in religious rituals, but principally for food rather than drink. The Shang court had been accoused of excessive drunkenness, and the Zhou, promoting the imperial Tian ("Heaven") as the prime spiritual force, rather than ancestors, limited wine in religious rites, in favour of food. The use of ritual bronzes continued into the early Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

One of the most commonly used motifs was the taotie, a stylized face divided centrally into 2 almoust mirror-image halves, with nostrils, eyes, eyebrows, jaws, cheeks and horns, surrounded by incised patterns. Whether taotie represented real, mythological or wholly imaginary creatures cannot be determined.

The enigmatic bronzes of Sanxingdui. near Guanghan (in Sichuan province), are evidence for a mysterious sacrificial religious system unlike anything elsewhere in ancient China and quite different from the art of the contemporaneous Shang at Anyang. Excavations at Sanxingdui since 1986 have revealed 4 pits containing artefacts of bronze, jade and gold. There was found a great bronze statue of a human figure which stands on a plinth decorated with abstract elephant heads. Besides the standing figure, the first 2 pits contained over 50 bronze heads, some wearing eadgear and 3 with a frontal covering of gold leaf.

Greek

Calyx krater with athletes in preparation for the competition; 510–500 BCE; found in Capua; Antikensammlung Berlin (Germany)

Venus de Milo; 130–100 BCE; marble; height: 203 cm (80 in); Louvre (Paris)

Greek and Etruscan artists built on the artistic foundations of Egypt, further developing the arts of sculpture, painting, architecture, and ceramics. Greek art started as smaller and simpler than Egyptian art, and the influence of Egyptian art on the Greeks started in the Cycladic islands between 3300–3200 BCE. Cycladic statues were simple, lacking facial features except for the nose.

Greek art eventually included life-sized statues, such as Kouros figures. The standing Kouros of Attica is typical of early Greek sculpture and dates from 600 BCE. From this early stage, the art of Greece moved into the Archaic Period. Sculpture from this time period includes the characteristic Archaic smile. This distinctive smile may have conveyed that the subject of the sculpture had been alive or that the subject had been blessed by the gods and was well.

Phoenician

Decorative plaque which depicts a fighting of man and griffin; 900–800 BCE; ivory: from Nimrud; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, USA)

Phoenician art lacks unique characteristics that might distinguish it from its contemporaries. This is due to its being highly influenced by foreign artistic cultures: primarily Egypt, Greece and Assyria. Phoenicians who were taught on the banks of the Nile and the Euphrates gained a wide artistic experience and finally came to create their own art, which was an amalgam of foreign models and perspectives.[17] In an article from The New York Times published on January 5, 1879, Phoenician art was described by the following:

He entered into other men's labors and made most of his heritage. The Sphinx of Egypt became Asiatic, and its new form was transplanted to Nineveh on the one side and to Greece on the other. The rosettes and other patterns of the Babylonian cylinders were introduced into the handiwork of Phoenicia, and so passed on to the West, while the hero of the ancient Chaldean epic became first the Tyrian Melkarth, and then the Herakles of Hellas.

Etruscan

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses; late 6th century BCE; terracotta; 1.14 m × 1.9 m (3.7 ft × 6.2 ft); Louvre (Paris)

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 9th and 2nd centuries BCE. From around 600 BCE it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta (especially life-size on sarcophagi or temples), wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.[18]

Etruscan sculpture in cast bronze was famous and widely exported, but relatively few large examples have survived (the material was too valuable, and recycled later). In contrast to terracotta and bronze, there was relatively little Etruscan sculpture in stone, despite the Etruscans controlling fine sources of marble, including Carrara marble, which seems not to have been exploited until the Romans.

The great majority of survivals came from tombs, which were typically crammed with sarcophagi and grave goods, and terracotta fragments of architectural sculpture, mostly around temples. Tombs have produced all the fresco wall-paintings, which show scenes of feasting and some narrative mythological subjects.

Dacian

The Helmet of Coțofenești; 4th century BCE; National History Museum of Romania (Bucharest, Romania)

Dacian art is the art associated with the peoples known as Dacians or North Thracians; The Dacians created an art style in which the influences of Scythians and the Greeks can be seen. They were highly skilled in gold and silver working and in pottery making. Pottery was white with red decorations in flolral, geometric, and stylized animal motifs. Similar decorations were worked in metal, especially the figure of a horse, which was common on Dacian coins.[19] Today, a big collection of Dacic masterpieces is in the National Museum of Romanian History (Bucharest), one of the most famous being the Helmet of Coțofenești.

The Geto-Dacians lived in a very large territory, stretching from the Balkans to the northern Carpathians and from the Black Sea and the river Tyras to the Tisa plain, sometimes even to the Middle Danube.[20] Between 15th–12th century, the Dacian-Getae culture was influenced by the Bronze Age Tumulus-Urnfield warriors.[21]

Pre-Roman Iberian

Pre-Roman Iberian art refers to the styles developed by the Iberians from the Bronze age up to the Roman conquest. For this reason it is sometimes described as "Iberian art".

Almost all extant works of Iberian sculpture visibly reflect Greek and Phoenician influences, and Assyrian, Hittite and Egyptian influences from which those derived; yet they have their own unique character. Within this complex stylistic heritage, individual works can be placed within a spectrum of influences- some of more obvious Phoenician derivation, and some so similar to Greek works that they could have been directly imported from that region. Overall the degree of influence is correlated to the work's region of origin, and hence they are classified into groups on that basis.

Hittite

The İvriz relief, king Warpalawas (right) before the god Tarhunzas

Hittite art was produced by the Hittite civilization in ancient Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey, and also stretching into Syria during the second millennium BCE from the nineteenth century up until the twelfth century BCE. This period falls under the Anatolian Bronze Age. It is characterized by a long tradition of canonized images and motifs rearranged, while still being recognizable, by artists to convey meaning to a largely illiterate population.

“Owing to the limited vocabulary of figural types [and motifs], invention for the Hittite artist usually was a matter of combining and manipulating the units to form more complex compositions"[22]

Many of these recurring images revolve around the depiction of Hittite deities and ritual practices. There is also a prevalence of hunting scenes in Hittite relief and representational animal forms. Much of the art comes from settlements like Alaca Höyük, or the Hittite capital of Hattusa near modern-day Boğazkale. Scholars do have difficulty dating a large portion of Hittite art, citing the fact that there is a lack of inscription and much of the found material, especially from burial sites, was moved from their original locations and distributed among museums during the nineteenth century.

Bactrian

The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age civilization of Central Asia, dated to c. 2300–1700 BCE, located in present-day northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus River). Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976).[citation needed]

BMAC materials have been found in the Indus Valley Civilisation, on the Iranian Plateau, and in the Persian Gulf.[23] Finds within BMAC sites provide further evidence of trade and cultural contacts. They include an Elamite-type cylinder seal and a Harappan seal stamped with an elephant and Indus script found at Gonur-depe.[24] The relationship between Altyn-Depe and the Indus Valley seems to have been particularly strong. Among the finds there were two Harappan seals and ivory objects. The Harappan settlement of Shortugai in Northern Afghanistan on the banks of the Amu Darya probably served as a trading station.[25]

A famous type of Bactrian artworks are the "Bactrian pricesses". Wearing large stylized dresses with puffed sleeves, as well as headdresses that merge with the hair, they embody the ranking goddess, character of the central Asian mythology that plays a regulatory role, pacifying the untamed forces.

Celtic

Detail of the Battersea Shield; 4th to 3rd century BCE; copper alloy and emanel; height: 77.5 cm (2 ft 6 in); British Museum (London)

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period. It also refers to the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

Celtic art is a difficult term to define, covering a huge expanse of time, geography and cultures. A case has been made for artistic continuity in Europe from the Bronze Age, and indeed the preceding Neolithic age; however archaeologists generally use "Celtic" to refer to the culture of the European Iron Age from around 1000 BCE onwards, until the conquest by the Roman Empire of most of the territory concerned, and art historians typically begin to talk about "Celtic art" only from the La Tène period (broadly 5th to 1st centuries BCE) onwards.[26] Early Celtic art is another term used for this period, stretching in Britain to about 150 CE.[27] The Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, which produced the Book of Kells and other masterpieces, and is what "Celtic art" evokes for much of the general public in the English-speaking world, is called Insular art in art history. This is the best-known part, but not the whole of, the Celtic art of the Early Middle Ages, which also includes the Pictish art of Scotland.[28]

Achaemenid

Achaemenid art includes frieze reliefs, metalwork, decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship (masonry, carpentry, etc.), and gardening. Most survivals of court art are monumental sculpture, above all the reliefs, double animal-headed Persian column capitals and other sculptures of Persepolis (see below for the few but impressive Achaemenid rock reliefs).[29]

Although the Persians took artists, with their styles and techniques, from all corners of their empire, they produced not simply a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style.[30] Cyrus the Great in fact had an extensive ancient Iranian heritage behind him; the rich Achaemenid gold work, which inscriptions suggest may have been a specialty of the Medes, was for instance in the tradition of earlier sites.

There are a number of very fine pieces of jewellery or inlay in precious metal, also mostly featuring animals, and the Oxus Treasure has a wide selection of types. Small pieces, typically in gold, were sewn to clothing by the elite, and a number of gold torcs have survived.[29]

Rome

Augustus of Prima Porta; 1st century CE; white marble; height: 2.03 m; Vatican Museums (Vatican City)

Roman art is sometimes viewed as derived from Greek precedents, but also has its own distinguishing features. Roman sculpture is often less idealized than the Greek precedents, being very realistic. Roman architecture often used concrete, and features such as the round arch and dome were invented.

Roman artwork was influenced by the nation-state's interaction with other people's, such as ancient Judea. A major monument is the Arch of Titus, which was erected by the Emperor Titus. Scenes of Romans looting the Jewish temple in Jerusalem are depicted in low-relief sculptures around the arch's perimeter.

Ancient Roman pottery was not a luxury product, but a vast production of "fine wares" in terra sigillata were decorated with reliefs that reflected the latest taste, and provided a large group in society with stylish objects at what was evidently an affordable price. Roman coins were an important means of propaganda, and have survived in enormous numbers.

Olmec

The Wrestler; basalt; height: 66 cm (26 in.); National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City). This carving is one of the finest examples of the formal quality of Late Olmec sculptures

Kunz axe; 1200–400 BCE; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)

The olmecs were the earliest known major civilization in Mesoamerica following a progressive development in Soconusco. They lived in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the present-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derive in part from neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque. The Olmecs flourished during Mesoamerica's formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BCE to about 400 BCE. Pre-Olmec cultures had flourished in the area since about 2500 BCE, but by 1600–1500 BCE, early Olmec culture had emerged, centered on the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán site near the coast in southeast Veracruz.[31] They were the first Mesoamerican civilization, and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed.

The Olmec culture was first defined as an art style, and this continues to be the hallmark of the culture.[32] Wrought in a large number of media – jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone among others – much Olmec art, such as The Wrestler, is naturalistic. Other art expresses fantastic anthropomorphic creatures, often highly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning.[33] Common motifs include downturned mouths and a cleft head, both of which are seen in representations of were-jaguars.[32]

Dong Son

The Dong Son culture (named for Đông Sơn, a village in Vietnam) was a Bronze Age culture in ancient Vietnam centred at the Red River Valley of northern Vietnam from 1000 BCE until the first century CE.[34]:207 It was the last great culture of Văn Lang and continued well into the period of the Âu Lạc state. Its influence spread to other parts of Southeast Asia, including Maritime Southeast Asia, from about 1000 BCE to 1 BCE.[35][36][37]

This culture is best known for its bronze drums, found in the tombs of the high-ranking persons. They are decorated with geometric and figurative motives (stylized animals and scenes from daily life).

Old Bering Sea

Old Bering Sea is an archaeological culture associated with a distinctive, elaborate circle and dot aesthetic style and is centered on the Bering Strait region; no site is more than 1 km from the ocean. Old Bering Sea is considered, following Henry B. Collins, the initial phase of the Northern Maritime tradition.[38] Despite its name, several OBS sites lie on the Chukchi Sea. The temporal range of the culture is from 400 BCE to possibly as late as CE 1300.[39]

The richly decorated objects are nearly exclusively on walrus tusk, some with distinctive color and antiquity; the decorations were applied to a very wide range of objects, many of which are recovered only in graves, some of which contain dozens of objects.[40] Old Bering Sea pieces are prized by art collectors in New York and Paris and the commoditization of the objects has fueled considerable looting of archaeological sites and spawned a quasi-legal trade (at least in the United States) termed subsistence digging.

European

Medieval

With the decline of the Roman Empire, the Medieval era began, lasting for a millennium. Early Christian art begins the period, followed by Byzantine art, Anglo-Saxon art, Viking art, Ottonian art, Romanesque art and Gothic art, with Islamic art dominating the eastern Mediterranean.

In Byzantine and Gothic art of the Middle Ages, the dominance of the church resulted in a large amount of religious art. There was extensive use of gold in paintings, which presented figures in simplified forms.

Byzantine

Byzantine art refers to the body of Christian Greek artistic products of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire,[41] as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from Rome's decline and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453,[42] the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Muslim states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

Icons (from the Greek εἰκών eikōn "image", "resemblance") are the most important visual elements in Byzantine religious practice, central to Orthodox worship since the end of Iconoclasm in the ninth century. Consistent in their format in order to preserve a sense of portraiture and the familiarity of favoured images, they have nevertheless transformed over time.

Carried by patriarchs in Eastern processions, read by monks in secluded caves and held by emperors at important ceremonies, sacred books, often beautifully illustrated, were central to Byzantine belief and ritual. Few manuscripts seem to have been produced in the Early Byzantine period between the sixth and eighth centuries CE, but there was a flourishing of painted books in the ninth century, following the end of Iconoclasm.

An unusual characteristic of Byzantine art are the golden backgronds. Clear glass was often backed with gold leafs to create a rich, shimmering effect.

Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norman Conquest of a large Anglo-Saxon nation-state whose sophisticated art was influential in much of northern Europe. The two periods of outstanding achievement were the 7th and 8th centuries, with the metalwork and jewellery from Sutton Hoo and a series of magnificent illuminated manuscripts, and the final period after about 950, when there was a revival of English culture after the end of the Viking invasions. By the time of the Conquest the move to the Romanesque style is nearly complete. The important artistic centres, in so far as these can be established, were concentrated in the extremities of England, in Northumbria, especially in the early period, and Wessex and Kent near the south coast.

Ottonian

The Essen cross with large enamels; part of the Essen Cathedral Treasury

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and northern Italy between 919 and 1024 under the kings Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Otto III and Henry II.[43] With Ottonian architecture, it is a key component of the Ottonian Renaissance (c. 951–1024). However, the style neither began nor ended to neatly coincide with the rule of the dynasty. It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own.[44] In the traditional scheme of art history, Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and precedes Romanesque art, though the transitions at both ends of the period are gradual rather than sudden. Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

Viking art

Viking art, also known commonly as Norse art, is a term widely accepted for the art of Scandinavian Norsemen and Viking settlements further afield—particularly in the British Isles and Iceland—during the Viking Age of the 8th–11th centuries CE. Viking art has many design elements in common with Celtic, Germanic, the later Romanesque and Eastern European art, sharing many influences with each of these traditions.[45]

Romanesque

Slavic

Saint Basil's Cathedral from the Red Square (Moscow). Its extraordinary onion-shaped domes, painted in bright colors, create a memorable skyline, making St. Basil's a symbol both of Moscow and Russia as a whole

Holy Trinity, Hospitality of Abraham; by Andrei Rublev; c. 1411; tempera on panel; 1.1 x 1.4 m (4 ft 8 in x 3 ft 83⁄4 in); Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow)

Lilies of the Valley, a Fabergé egg; 1898; enamel, gold, diamonds, rubies & pearls; 15.1 cm (5.9 in) when is closed; Fabergé Museum (Saint Petersburg, Russia)

Slavic architecture is a mix of Byzantine and Pagan architecture. Some characteristics taken from the Slavic pagan temples are the exterior galleries and the plurality of towers. Most iconic buildings are the Russian and Ukrainian cathedrals. These cathedrals are well known for their unsusual onion domes, which are decorated with geometric and colorful patterns. It is not completely clear when and why onion domes became a typical feature of Russian architecture. Byzantine churches and the architecture of Kievan Rus were characterized by broader, flatter domes without a special framework erected above the drum. In contrast to this ancient form, each drum of a Russian church is surmounted by a special structure of metal or timber, which is lined with sheet iron or tiles. Russian architecture used the dome shape not only for churches but also for other buildings.

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 988 CE. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by usage, some of which had originated in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians—notably Andrei Rublev and Dionisius—widened the vocabulary of iconic types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere. The personal, improvisatory and creative traditions of Western European religious art are largely lacking in Russia before the seventeenth century, when Simon Ushakov's painting became strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from Protestant as well as Catholic Europe.

Renaissance

Mona Lisa; by Leonardo da Vinci; c. 1503–1506, perhaps continuing until c. 1517; oil on poplar panel; Louvre (Paris)

The Garden of Earthly Delights; by Hieronymus Bosch; c. 1504; oil on panel; 2.2 x 1.95 m (7 ft 21⁄2 in.) – central panel; Museo del Prado (Madrid, Spain)

The Renaissance is the return to a valuation of the material world, and this paradigm shift is reflected in art forms, which show the corporeality of the human body, and the three-dimensional reality of landscapes. Art historians often periodize Renaissance art by century, especially with Italian art. Italian Renaissance and Baroque art is traditionally referred to by centuries: trecento for the fourteenth century, quattrocento for the fifteenth, cinquecento for the sixteenth, and seicento for the seventeenth.

Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassicism

The Swing; by Jean-Honoré Fragonard; 1767–1768; oil on canvas; height: 81 cm (317⁄8 in.), width: 64 cm (251⁄4 in.); Wallace Collection (London)

Neoclassical vase; 1828; produced in the Imperial Porcelain Factory (Saint Petersburg, Russia)

Baroque and Rococo were 2 highly ornamental and theatrical styles of decoration which combine scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colors and sculpted molding. Neoclassicism draw inspiration from the "classical" art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was born largely thanks to the writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, at the time of the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum, but its popularity spread all over Europe as a generation of European art students finished their Grand Tour and returned from Italy to their home countries with newly rediscovered Greco-Roman ideals.[46][47]

Romanticism and realism

The 18th and 19th centuries included Romanticism, and Realism in art.

Middle Eastern

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Decorated capital of a pillar from the royal palace of Shabwa; stratigraphic context: first half of the 3rd century BCE; National Museum of Yemen (Aden)

The art of Pre-Islamic Arabia is related to that of neighbouring cultures. Pre-Islamic Yemen produced stylized alabaster heads of great aesthetic and historic charm. Most of the pre-Islamic sculptures are made of alabaster.

Archaeology has revealed some early settled civilizations in Saudi Arabia: the Dilmun civilization on the east of the Arabian Peninsula, Thamud north of the Hejaz, and Kindah kingdom and Al-Magar civilization in the central of Arabian Peninsula.

The earliest known events in Arabian history are migrations from the peninsula into neighbouring areas.[48] In antiquity, the role of South Arabian societies such as Saba (Sheba) in the production and trade of aromatics not only brought such kigdoms wealth but also tied the Arabian peninsula into trade networks, resulting in far-ranging artistic influences.

It seems probable that before around 4000 BCE the Arabian climate was somewhat wetter that today, benefitting from a monsoon system that has since moved south.[citation needed] During the late fourth millennium BCE permanent settlements began to appear, and inhabitants adjusted to the emerging dryer conditions. In south-west Arabia (modern Yemen) a moister climate supported several kingdoms during the second and first millennia BCE. The most famos of these is Sheba, the kingdom of the biblical Queen of Sheba. These societies used a combination of trade in spices and the natural resources of the region, including aromatics such as frankincense and myrrh, to build wealthy kingdoms. Mārib, the Sabaean capital, was well positioned to tap into Mediterranean as well as Near Eastern trade, and in kingdoms to the east, in what is today Oman, trading links with Mesopotamia, Persia and even India were possible. The area was never a part of the Assyrian or Persian empires, and even Babylonian control of north-west Arabia seems to have been relatively short-lived. Later Roman attempts to control the region's lucrative trade foundered. This impenetrability to foreign armies doubtless augmented ancient rulers' bargaining power in the spice and incense trade.

Although subject to external influences, south Arabia retained characteristics particular to itself. The human figure is typically based on strong, square shapes, the fine modeling of detail contrastingwith a stylized simplicity of form.

Islamic

Qajar dynasty rock reliefs in Tangeh Savashi (Iran); c. 1800 (the Fath Ali Shah era)

Some branches of Islam forbid depictions of people and other sentient beings, as they may be misused as idols. Religious ideas are thus often represented through geometric designs and calligraphy. However, there are many Islamic paintings which display religious themes and scenes of stories common among the three Abrahamic monotheistic faiths of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism.

The influence of Chinese ceramics has to be viewed in the broader context of the considerable importance of Chinese culture on Islamic arts in general.[49] The İznik pottery (named after İznik, a city from Turkey) is one of the best well-known types of Islamic pottery. Its famous combination between blue and white is a result of that Ottoman court in Istanbul who greatly valued Chinese blue-and-white porcelain.

Siberian-Eskimo

Yupik mask; 19th century; from Alaska; Musée du Quai Branly (Paris)

The art of the Eskimo people from Siberia is in the same style as the Inuit art from Alaska and north Canada. This is because the Native Americans traveled through Siberia to Alaska, and later to the rest of the Americas.[citation needed]

Including the Russian Far East, the population of Siberia numbers just above 40 million people. As a result of the 17th-to-19th-century Russian conquest of Siberia and the subsequent population movements during the Soviet era, the demographics of Siberia today is dominated by native speakers of Russian. There remain a considerable number of indigenous groups, between them accounting for below 10% of total Siberian population, which are also genetically related to Indigenous Peoples of the Americas.

Americas

Kunz Axe; 1000–400 BCE; jadeite; height: 31 cm (123⁄16 in.), width 16 cm (65⁄16 in.), 11 cm (45⁄16 in.); American Museum of Natural History (Washington, DC). The jade Kunz Axe, first described by George Kunz in 1890. Although shaped like an axe head, with an edge along the bottom, it is unlikely that this artifact was used except in ritual settings. At a height of 28 cm (11 in), it is one of the largest jade objects ever found in Mesoamerica.[50]

The history of art in the Americas begins in pre-Columbian times with Indigenous cultures. Art historians have focused particularly closely on Mesoamerica during this early era, because a series of stratified cultures arose there that erected grand architecture and produced objects of fine workmanship that are comparable to the arts of Western Europe.

Preclassic

The art-making tradition of Mesoamerican people begins with the Olmec around 1400 BCE, during the Preclassic era. These people are best known for making colossal heads but also carved jade, erected monumental architecture, made small-scale sculpture, and designed mosaic floors. Two of the most well-studied sites artistically are San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán and La Venta. After the Olmec culture declined, the Maya civilization became prominent in the region. Sometimes a transitional Epi-Olmec period is described, which is a hybrid of Olmec and Maya. A particularly well-studied Epi-Olmec site is La Mojarra, which includes hieroglyphic carvings that have been partially deciphered.

Classic

Zapotec mosaic mask that represents a Bat god, made of 25 pieces of jade, with yellow eyes made of shell. It was found in a tomb at Monte Alban

By the late pre-Classic era, beginning around 400 BCE, the Olmec culture had declined but both Central Mexican and Maya peoples were thriving. Throughout much of the Classic period in Central Mexico, the city of Teotihuacan was thriving, as were Xochicalco and El Tajin. These sites boasted grand sculpture and architecture. Other Central Mexican peoples included the Mixtecs, the Zapotecs, and people in the Valley of Oaxaca. Maya art was at its height during the “Classic” period—a name that mirrors that of Classical European antiquity—and which began around 200 CE. Major Maya sites from this era include Copan, where numerous stelae were carved, and Quirigua where the largest stelae of Mesoamerica are located along with zoomorphic altars. A complex writing system was developed, and Maya illuminated manuscripts were produced in large numbers on paper made from tree bark. Many sites ”collapsed” around 1000 CE.

Postclassic

At the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatán during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Maya were still powerful, but many communities were paying tribute to Aztec society. The latter culture was thriving, and it included arts such as sculpture, painting, and feather mosaics. Perhaps the most well-known work of Aztec art is the calendar stone, which became a national symbol of the state of Mexico. During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, many of these artistic objects were sent to Europe, where they were placed in cabinets of curiosities, and later redistributed to Western art museums. The Aztec empire was based in the city of Tenochtitlan which was largely destroyed during the colonial era. What remains of it was buried beneath Mexico City. A few buildings, such as the foundation of the Templo Mayor have since been unearthed by archaeologists, but they are in poor condition.

Art in the Americas

Art in the Americas since the conquest is characterized by a mixture of indigenous and foreign traditions, including those of European, African, and Asian settlers. Numerous indigenous traditions thrived after the conquest. For example, the Plains Indians created quillwork, beadwork, winter counts, ledger art, and tipis in the pre-reservation era, and afterwards became assimilated into the world of Modern and Contemporary art through institutions such as the Santa Fe Indian School which encouraged students to develop a unique Native American style. Many paintings from that school, now called the Studio Style, were exhibited at the Philbrook Museum of Art during its Indian annual held from 1946 to 1979.

Aztec

Arising from the humblest beginnings as a nomadic group of "uncivilizated" wanderers, the Aztecs created the largest empire in Mesoamerican history, lasting from 1427/1428 to 1521. Tribute from conquered states provided the economic and artistic resources to transform their capital Tenochtitlan (0ld Mexico City) into one of the wonders of the world. Artists from through mesoamerica creted stunning artworks for their new maters, fashioning delicate golden objects of personal adornment and formidable sculptures of firece gods.

The Aztecs entered the Valley of Mexico (the area of modern Mexico City) in 1325 and within a centry had taken control of this lush region brimming with powerful city-states. Their power was based on umbending faith in the vision of their patron deity Huitzilopochtli, a god of war, and in their own unparalleled military prowess.

The grandiosity of the Aztec state was reflected in the comportment of the nobility and warriors who had distinguished themselves in battle. Their finelty woven and richly embellished clothing was accentuated by iridescent tropical bird feathers amd ornate jewellery made of gold, silver, semi-precious stones and rare shells.

Aztec art may be direct and dramatic or subtle and delicate, depending on the function of the work. The finest pieces, from monumental sculptures to masks and gold jewellery, display outstanding craftsmanship and aesthetic refinement. This same sophistication characterizes Aztec poetry, which was renowned for its lyrical beauty and spiritual depth. Aztec feasts were not complete without a competitive exchange of verbal artistry among the finely dressed noble guests.

Mayan

Jade plaque of a Maya king; 400–800 (Classic period); height: 14 cm, width: 14 cm; found at Teotihuacan; British Museum (London)

Codex-style vase with a mythological scene; 7th–8th century; cdramic; height: 19 cm (71⁄2 in.), diameter: 11.2 cm (47⁄16 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Ancient Maya art refers to the material arts of the Maya civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture that took shape in the course of the later Preclassic Period (500 BCE to 200 CE). Its greatest artistic flowering occurred during the seven centuries of the Classic Period (c. 200 to 900 CE). Ancient Maya art then went through an extended Post-Classic phase before the upheavals of the sixteenth century destroyed courtly culture and put an end to the Mayan artistic tradition. Many regional styles existed, not always coinciding with the changing boundaries of Maya polities. Olmecs, Teotihuacan and Toltecs have all influenced Maya art. Traditional art forms have mainly survived in weaving and the design of peasant houses.

The jade artworks count among the most wonderful works of art the Maya have left us. The majority of items found date back to the Classic period, but more and more artefacts dating back to the Preclassic are being discovered. The earliest of these include simple, unadorned beads found in burials in Cuello (Belize) dating back to between 1200 and 900 BC. At the time, stone cutting was already highly developed among the Olmecs, who were already working jade before the Maya. In Mesoamerica, jade is found solely as jadeite; nephrite, the other variety known as jade, does not exist there. However, in this area of Mesoamerica "jade" is a collective term for a number of other green or blue stones. Jade objects were placed in burials, used in rituals and, of course, as jewelry. As well as being used for beads, which were often strung together to make highly ornate pendants and necklaces, they were also used for ear spools, arm, calf and foot bands, belts, pectorals (chest jewelry), and to adorn garments and haddresses.

Ancient Maya art is renowned for its aesthetic beauty and narrative content. Of all the media in which Maya artists worked, their paintings on pottery are among the most impressive because of their technical and aesthetical sophistication. These complex pictoral scenes accompanied by hieroglyphic texts recount historic events of the Classic period and reveal the religious ideology upon which the Maya built a great civilization.

Costa Rica and Panama

Long considered a backwater of culture and aesthetic expression, Central America's dynamic societies are now recognized as robust and innovative contributors to the arts of ancient Americas. The people of pre-Columbian Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama developed their own distinctive styles in spite of the region being a crossroads for millennia. Its peoples were not subsumed by outside influences but instead created, adopted and adapted al manner of ideas and technologies to suit their needs and temperaments. The region's isiosyncratic cultural traditions, religious beliefs and sociopolitical systems are reflected in unique artworks. A fundamental spiritual tenet was shamanism, the central principle of which decreedthat in a trance state, transformed into one's spirit companion form, a person could enter the supranatural realm and garner special power to affect worldly affairs. Central American artists devised ingenious ways to portray this transformation by merging into one figure human and animal characteristics; the jaguar, serpent and avian raport (falcon, eagle or vulture) were the main spirit forms.

Colombia

Tairona anthopomorphic pendant; 1000–1550; gold alloy casting; width: 14.6 cm (53⁄4 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Quimbaya lime container; 5th–9th century; gold; 23 cm (9 in) high; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Yotoco animal-headed figure pendant; 1st–7th century; gold; height: 6.35 cm (21⁄2 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gold — the perpetually brilliant metal of status, wealth and power — inspired the Spanish to explore the globe and was an essential accoutrement of prestige, authority and religious ideology among the people of Central America and Colombia.

In Colombia, gold was important for its relationship to thedivine force of the sun. It was part of a complex ideology of universal binary oppositions: male-female, light-dark, the earth and spirit worlds. Gold body adornments were cast in complex forms, their iconography communicating social, political and spiritual potency through portrayals of powerful shaman-rulers, lineage totems and supranatural protector spirits.

Andean regions

Moche portrait vessel of a ruler; 100 BC-500 AD; ceramic & pigment; Art Institute of Chicago (USA)

The ancient civilizations of Peru and Bolivia nurtured unique artistic traditions, including one of the world's most aesthetically impressive fibre art traditions, seen on artifacts from clothing to burial shrouds to architectural embellishment. The origins of Andean civilization reach back before 3000 BC. Harnessing the challenging environments – which included the world's driest coastal desert, desolate windswept highlands and formidable mountains – Andean pre-Columbian people excelled in agriculture, marine fishing and animal husbandry. By 1800 BC ritual and civic buildings elevated on massive adobe platforms dominated the larger settlements, particularly in the coastal river valleys. Two of the first important cultures from this land are the Chavín and the Paracas culture.

The Moche controlled the river valleys of the north coast, while the Nazca of southern Peru held sway along the coastal deserts and contiguous mountains, inheriting the technological advances – in agriculture and architecture – as well as the artistic traditions of the earlier Paracas people. Both cultures flourished around 100–800 AD. Moche pottery is some of the most varied in the world. The use of mold technology is evident. This would have enabled the mass production of certain forms. The Following the decline of the Moche, two large co-existing empires emerged in the Andes region. In the north, the Wari (or Huari) Empire. The Wari are noted for their stone architecture and sculpture accomplishments, but their greatest proficiency was ceramic. The Wari produced magnificent large ceramics, many of which depicted images of the Staff God.

The Chimú were preceded by a simple ceramic style known as Sicán (700–900 AD) which became increasingly decorative until it became recognizable as Chimú in the early second millennium. The Chimú produced excellent portrait and decorative works in metal, notably gold but especially silver. The Chimú also are noted for their featherwork, having produced many standards and headdresses made of a variety of tropical feathers which were fashioned into bired and fish designs, both of which were held in high esteem by the Chimú.

Amazonia and the Caraibbes

Taino deity figure (Zemi); 15th–16th century CE; wood & shell; probably from the Dominican Republic; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Marajoara cylindrical vessel; 400–1000 CE; ceramic with creamy white slip under reddish brown paint; height: 38.5 cm; from the Marajó island (Brazil)

The tropical climate of the Caraibbean islands and the Amazonian rainforest is not favorable to the preservation of artefacts made from wood and other materials. What survived reveals complex societies whose people created art rich in mythological and spiritual meaning.

The Taino people, who occupied the Caraibbean islands when the Spanish arrived, were agriculturalists whose society was centred on hereditary chiefs called caciques. Their towns included impressively constructed ceremonial plazas in which ball games were played and religious rituals carried on, linking their culture to that of the Maya from the Yucatán Peninsula. Much of Taino art was associated with shamanic rituals and religion, including a ritual in which a shaman or a cacique enters into a hypnotic state by inhaling the hallucinogetic cohoba powder. Sculptures representing the creator god Yocahu often depict a nude male figure in a squatting position with a slightly concave dish on top of his head, to hold the cohoba powder. Other figures (always male) stand rigidly frontal, the ostentatious display of their genitals apparently to the importance of fertility. The purpose of these rituals was communication with the ancestors and the spirit world. Chiefs and shamans (often the same person) sometimes interceded with spirit beings from a sculpted stool, or duho.

Meanwhile, the Marajoara culture flourished on Marajó island at the mouth of the Amazon River, in Brazil. Archeologists have found sophisticated pottery in their excavations on the island. These pieces are large, and elaborately painted and incised with representations of plants and animals. These provided the first evidence that a complex society had existed on Marajó. Evidence of mound building further suggests that well-populated, complex and sophisticated settlements developed on this island, as only such settlements were believed capable of such extended projects as major earthworks.[51] The pottery that they made is decorated with abastract lines and spirals, suggesting that they probably consumed hallucinogetic plants. The Marajoara culture produced many kinds of vessels including urns, jars, bottles, cups, bowls, plates and dishes.

United States and Canada

Kwakwaka'wakw whale figure; 19th century; cedar wood, hide, cotton cord, nails & pigment; 60 x 72.4 x 206 cm (235⁄8 x 281⁄2 x 811⁄8 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

Hopi vassel; 19th century; ceramic with pigments; from Arizona; Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts (California)

The most famous native American art style from the United States and Canada is the one of the Northwest Coast, famous for their totems and color combinations.

The art of the Haida, Tlingit, Heiltsuk, Tsimshian and other smaller tribes living in the coastal areas of Washington State, Oregon, and British Columbia, is characterized by an extremely complex stylistic vocabulary expressed mainly in the medium of woodcarving. Famous examples include totem poles, transformation masks, and canoes. In addition to woodwork, two dimensional painting and silver, gold and copper engraved jewelry became important after contact with Europeans.

The Eastern Woodlands, or simply woodlands, cultures inhabited the regions of North America east of the Mississippi River at least since 2500 BCE. While there were many regionally distinct cultures, trade between them was common and they shared the practice of burying their dead in earthen mounds, which has preserved a large amount of their art. Because of this trait the cultures are collectively known as the Mound builders.

Inuit

Yupik mask with seal or sea otter spirit; late 19th century; wood, paint, gut cord, & feathers; Dallas Museum of Art (Texas, USA)

Inuit art refers to artwork produced by Inuit people, that is, the people of the Arctic previously known as Eskimos, a term that is now often considered offensive outside Alaska. Historically, their preferred medium was walrus ivory, but since the establishment of southern markets for Inuit art in 1945, prints and figurative works carved in relatively soft stone such as soapstone, serpentinite, or argillite have also become popular. The range of colors is cold, most encountered being: black, brown, grays, white and gray-blue.

The Winnipeg Art Gallery has a large public collection of contemporary Inuit art.[52] In 2007, the Museum of Inuit Art opened in Toronto,[53] but closed due to lack of resources in 2016.[54] Carvings Nunavut, owned by Inuk Lori Idlout, opened in 2008 and has grown to have the largest private collection in Nunavut. The Inuit owned and operated gallery includes a wide selection of Inuit made art that has millions in inventory.[55]

Asian art

The Great Wave off Kanagawa; by Katsushika Hokusai; circa 1830–1832; full-colour woodblock print; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Eastern civilization broadly includes Asia, and it also includes a complex tradition of art making. One approach to Eastern art history divides the field by nation, with foci on Indian art, Chinese art, and Japanese art. Due to the size of the continent, the distinction between Eastern Asia and Southern Asia in the context of arts can be clearly seen. In most of Asia, pottery was a prevalent form of art. The pottery is often decorated with geometric patterns or abstract representations of animals, people or plants. Other very widespread forms of art were, and are, sculpture and painting.

Central Asia

Suzani (ceremonial hanging); late 1700s; cotton; 92 x 631⁄4 in.; from Uzbekistan; Indianapolis Museum of Art

Suzani; late 19th-early 20th century; cotton, plain weave & embroidery; from Uzbekistan; Honolulu Museum of Art (Hawaii, USA)

Superb samples of Steppes art – mostly golden jewellery and trappings for horse – are found over vast expanses of land stretching from Hungary to Mongolia. Dating from the period between the 7th and 3rd centuries BCE, the objects are usually diminutive, as may be expected from nomadic people always on the move. Art of the steppes is primarily an animal art, i.e., combat scenes involving several animals (real or imaginary) or single animal figures (such as golden stags) predominate. The best known of the various peoples involved are the Scythians, at the European end of the steppe, who were especially likely to bury gold items.

Among the most famous finds was made in 1947, when the Soviet archaeologist Sergei Rudenko discovered a royal burial at Pazyryk, Altay Mountains, which featured – among many other important objects – the most ancient extant pile rug, probably made in Persia. Unusually for prehistoric burials, those in the northern parts of the area may preserve organic materials such as wood and textiles that normally would decay. Steppes people both gave and took influences from neighbouring cultures from Europe to China, and later Scythian pieces are heavily influenced by ancient Greek style, and probably often made by Greeks in Scythia.

Indian

The Indus Valley Civilisation made anthropomorphic figures. Most famous are the Dancing Girl and the Priest-King. This civilisation made also many clay pots, most of them decorated with geometric patterns. They made seals decorated with animals, anthropomorphic figures and their script. The Indus script (also known as the Harappan script) is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilization during the Kot Diji and Mature Harappan periods between 3500 and 1900 BCE. Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not these symbols constituted a script used to record a language, or even symbolise a writing system.[56] In spite of many attempts,[57] the "script" has not yet been deciphered, but efforts are ongoing. There is no known bilingual inscription to help decipher the script, nor does the script show any significant changes over time. However, some of the syntax (if that is what it may be termed) varies depending upon location.[56]

Early Buddhists in India developed symbols related to Buddha. Bhutanese painted "thangkas" that shows Buddhist iconography. The major survivals of Buddhist art begin in the period after the Mauryans, from which good quantities of sculpture survives from some key sites such as Sanchi, Bharhut and Amaravati, some of which remain in situ, with others in museums in India or around the world. Stupas were surrounded by ceremonial fences with four profusely carved toranas or ornamental gateways facing the cardinal directions. These are in stone, though clearly adopting forms developed in wood. They and the walls of the stupa itself can be heavily decorated with reliefs, mostly illustrating the lives of the Buddha. Gradually life-size figures were sculpted, initially in deep relief, but then free-standing.[58]Mathura was the most important centre in this development, which applied to Hindu and Jain art as well as Buddhist.[59] The facades and interiors of rock-cut chaitya prayer halls and monastic viharas have survived better than similar free-standing structures elsewhere, which were for long mostly in wood. The caves at Ajanta, Karle, Bhaja and elsewhere contain early sculpture, often outnumbered by later works such as iconic figures of the Buddha and bodhisattvas, which are not found before 100 CE at the least.

Nepalese, Bhutanese, and Tibetan

For more than a thousand years, Tibetan artists have played a key role in the cultural life of Tibet. From designs for painted furniture to elaborate murals in religious buildings, their efforts have permeated virtually every facet of life on the Tibetan plateau. The vast majority of surviving artworks created before the mid-20th century are dedicated to the depiction of religious subjects, with the main forms being thangka, distemper paintings on cloth, Tibetan Buddhist wall paintings, and small statues in bronze, or large ones in clay, stucco or wood. They were commissioned by religious establishments or by pious individuals for use within the practice of Tibetan Buddhism and were manufactured in large workshops by monks and lay artists, who are mostly unknown.

The art of Tibet may be studied in terms of influences which have contributed to it over the centuries, from other Chinese, Nepalese, Indian, and sacred styles. Many bronzes in Tibet that suggest Pala influence, are thought to have been either crafted by Indian sculptors or brought from India.[60]

Bhutanese art is similar to the art of Tibet. Both are based upon Vajrayana Buddhism, with its pantheon of divine beings. The major orders of Buddhism in Bhutan are Drukpa Kagyu and Nyingma. The former is a branch of the Kagyu School and is known for paintings documenting the lineage of Buddhist masters and the 70 Je Khenpo (leaders of the Bhutanese monastic establishment). The Nyingma order is known for images of Padmasambhava, who is credited with introducing Buddhism into Bhutan in the 7th century. According to legend, Padmasambhava hid sacred treasures for future Buddhist masters, especially Pema Lingpa, to find. The treasure finders (tertön) are also frequent subjects of Nyingma art.

Chinese

Wang Xizhi watching geese; by Qian Xuan; 1235-before 1307; handscroll (ink, color and gold on paper); 91⁄8 x 361⁄2 in.; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Qilin-shaped incense burner; 17th–18th centuries (Qing Dynasty); cloisonné; Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts (Stanford, California)

In Eastern Asia, painting was derived from the practice of calligraphy, and portraits and landscapes were painted on silk cloth. Most of the paintings represent landscapes or portraits. The most spectacular sculptures are the ritual bronzes and the bronze sculptures from Sanxingdui. A very well-known example of Chinese art is the Terracotta Army, depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE whose purpose was to protect the emperor in his afterlife.

Chinese art is one of the oldest continuous traditional arts in the world, and is marked by an unusual degree of continuity within, and consciousness of, that tradition, lacking an equivalent to the Western collapse and gradual recovery of classical styles. The media that have usually been classified in the West since the Renaissance as the decorative arts are extremely important in Chinese art, and much of the finest work was produced in large workshops or factories by essentially unknown artists, especially in Chinese ceramics.

Japanese

Kakiemon octagonal bottle with long neck, decorated with flowering trees; 1675–1725; glazed porcelain; Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam, the Netherlands)

Three Beauties of the Present Day; by Kitagawa Utamaro; circa 1793; height: 3.87 cm (15.23 in), width: 2.62 cm (10.31 in); Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio)

Inrō; 18th–19th century; carved red lacquer; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture, ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper, ukiyo-e paintings and woodblock prints, ceramics, origami, and more recently manga—modern Japanese cartooning and comics—along with a myriad of other types.

The first settlers of Japan, the Jōmon people (c. 11,000–300 BCE). They crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogū. Japan has been subject to sudden invasions of new ideas followed by long periods of minimal contact with the outside world. Over time the Japanese developed the ability to absorb, imitate, and finally assimilate those elements of foreign culture that complemented their aesthetic preferences. The earliest complex art in Japan was produced in the 7th and 8th centuries in connection with Buddhism. In the 9th century, as the Japanese began to turn away from China and develop indigenous forms of expression, the secular arts became increasingly important; until the late 15th century, both religious and secular arts flourished. After the Ōnin War (1467–1477), Japan entered a period of political, social, and economic disruption that lasted for over a century. In the state that emerged under the leadership of the Tokugawa shogunate, organized religion played a much less important role in people's lives, and the arts that survived were primarily secular.

Korean

Dragon-shaped celadon ewer; 12th century; National Museum of Korea (Soul, South Korea). This kettle symbolizes a dragon (fish dragon) jumping up and running

Korean arts include traditions in calligraphy, music, painting and pottery, often marked by the use of natural forms, surface decoration and bold colors or sounds.

The earliest examples of Korean art consist of stone age works dating from 3000 BCE. These mainly consist of votive sculptures and more recently, petroglyphs, which were rediscovered.

This early period was followed by the art styles of various Korean kingdoms and dynasties. Korean artists sometimes modified Chinese traditions with a native preference for simple elegance, spontaneity, and an appreciation for purity of nature.

The Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) was one of the most prolific periods for a wide range of disciplines, especially pottery.

The Korean art market is concentrated in the Insadong district of Seoul where over 50 small galleries exhibit and occasional fine arts auctions. Galleries are cooperatively run, small and often with curated and finely designed exhibits. In every town there are smaller regional galleries, with local artists showing in traditional and contemporary media. Art galleries usually have a mix of media. Attempts at bringing Western conceptual art into the foreground have usually had their best success outside of Korea in New York, San Francisco, London and Paris.

Vietnamese

Seated deity; late 9th; sandstone; from Champa (Quang Nam Province, Temple Complex of Dong-du'o'ng); Rietberg Museum (Zürich, Switzerland)

Vietnamese art has a long and rich history. With the millennium of Chinese domination starting in the 2nd century BCE, Vietnamese art undoubtedly absorbed many Chinese influences, which would continue even following independence from China in the 10th century CE. It was also influenced by Khmer art. However, Vietnamese art has always retained many distinctively Vietnamese characteristics.

By the 19th century, the influence of French art took hold in Vietnam, having a large hand in the birth of modern Vietnamese art.

Thai

Hanuman on his chariot, a scene from the Ramakien in Wat Phra Kaew (Bangkok)

Traditional Thai art is primarily composed of Buddhist art and scenes from the Indian epics. Traditional Thai sculpture almost exclusively depicts images of the Buddha, being very similar with the other styles from Southeast Asia, such as Khmer. Traditional Thai paintings usually consist of book illustrations, and painted ornamentation of buildings such as palaces and temples. Over time, thai art was influenced by the other Asian styles, most by Indian and Khmer. Thai sculpture and painting, and the royal courts provided patronage, erecting temples and other religious shrines as acts of merit or to commemorate important events.

Cambodian/Khmer