Worcester

City of Worcester | ||

|---|---|---|

Cathedral City and non-metropolitan district | ||

Worcester Cathedral from Fort Royal Hill | ||

| ||

City of Worcester shown within Worcestershire | ||

| Coordinates: 52°11′31″N 2°13′12″W / 52.192°N 2.220°W / 52.192; -2.220Coordinates: 52°11′31″N 2°13′12″W / 52.192°N 2.220°W / 52.192; -2.220 | ||

| Sovereign state | Britain | |

| Constituent country | England | |

| Region | West Midlands | |

| Non-metropolitan county | Worcestershire | |

| Status | Non-metropolitan district, City | |

| Admin HQ | Worcester | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Non-metropolitan district council | |

| • Borough council | Worcester City Council (Shared) | |

| • MPs | Robin Walker (Conservative) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 33.28 km2 (12.85 sq mi) | |

| Area rank | 305th (of 326) | |

| Population (mid-2015) | ||

| • Total | 101,328 | |

| • Rank | 233rd (of 326) | |

| • Density | 3,000/km2 (7,900/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) | |

| Postcodes | WR1-5 | |

| Area code(s) | 01905 | |

| ONS code | 47UE (ONS) E07000237 (GSS) | |

| OS grid reference | SO849548 | |

| Website | www.worcester.gov.uk | |

Worcester (/ˈwʊstər/ (![]() listen) WUUS-tər) is a city in Worcestershire, England, 31 miles (50 km) southwest of Birmingham, 101 miles (163 km) west-northwest of London, 27 miles (43 km) north of Gloucester and 23 miles (37 km) northeast of Hereford. The population is approximately 100,000. The River Severn flanks the western side of the city centre, which is overlooked by Worcester Cathedral.

listen) WUUS-tər) is a city in Worcestershire, England, 31 miles (50 km) southwest of Birmingham, 101 miles (163 km) west-northwest of London, 27 miles (43 km) north of Gloucester and 23 miles (37 km) northeast of Hereford. The population is approximately 100,000. The River Severn flanks the western side of the city centre, which is overlooked by Worcester Cathedral.

The Battle of Worcester was the final battle of the English Civil War, where Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army defeated King Charles I's Cavaliers. Worcester is known as the home of Royal Worcester Porcelain, composer Edward Elgar,[1]Lea & Perrins, makers of traditional Worcestershire sauce, University of Worcester, and Berrow's Worcester Journal, claimed to be the world's oldest newspaper.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Early history

1.2 Roman and British

1.3 Anglo-Saxon town: Roman origins

1.4 Medieval

1.4.1 Early medieval

1.4.2 Jewish life, persecution and expulsions

1.4.3 Late medieval

1.5 Evolution of craft guilds

1.6 Early modern

1.6.1 Civil war

1.6.2 After the Restoration

1.7 Industrial revolution and Victorian

1.8 Twentieth century to present

1.9 Images

2 Governance

3 Geography

3.1 Climate

3.2 Green belt

4 Demography and religion

5 Economy

5.1 Glove industry

5.2 Manufacturing

5.3 Retail trade

6 Landmarks

7 Transport

7.1 Road

7.2 Rail

7.3 Bus

7.4 Air

8 Education

8.1 High schools

8.2 Independent schools

9 Sport

10 Culture

10.1 Festivals and shows

10.2 Arts and cinema

10.3 Media

10.3.1 Newspapers

10.3.2 Radio Stations

11 In popular culture

12 Twinning and planned twinning

13 Notable people

14 See also

15 Notes

16 References

16.1 General Worcester sources

16.2 Sources: Medieval history

16.3 Sources: Civil War

16.4 General sources

16.5 Further reading

17 External links

History

Early history

The trade route which ran past Worcester, later forming part of the Roman Ryknild Street, dates to Neolithic times. The position commanded a ford over the River Severn (the river was tidal past Worcester prior to public works projects in the 1840s) and was fortified by the Britons around 400 BC. It would have been on the northern border of the Dobunni and probably subject to the larger communities of the Malvern hillforts.[2]

Roman and British

The Roman settlement at the site passes unmentioned by Ptolemy's Geography, the Antonine Itinerary and the Register of Dignitaries, but would have grown up on the road opened between Glevum (Gloucester) and Viroconium (Wroxeter) in the 40s and 50s AD. It may have been the "Vertis" mentioned in the 7th century Ravenna Cosmography. Using charcoal from the Forest of Dean, the Romans operated pottery kilns and ironworks at the site[3] and may have built a small fort.[4] There is no sign of municipal buildings that would indicate an administrative role.[5]

In the 3rd century, Roman Worcester occupied a larger area than the subsequent medieval city, but silting of the Diglis Basin caused the abandonment of Sidbury. Industrial production ceased and the settlement contracted to a defended position along the lines of the old British fort at the river terrace's southern end.[6]

This settlement is generally identified with the Cair Guiragon[7] listed among the 28 cities of Britain in the History of the Britons attributed to Nennius.[8][9] This is probably not a British name but an adaption of its Old English name Weorgoran ceaster, "fort of the Weorgoran".[a]

Anglo-Saxon town: Roman origins

The form of the place-name varied as language and history developed over the centuries, with Early English and subsequent Norman French additions. At its settlement in 7th century by the Angles of Mercia it was known as Weogorna. After centuries of warfare against the Vikings and Danelaw it a centre for the Anglo-Saxon army or here known as Weogorna ceastre (Worcester Camp). At the time of Tenth Century Reformation[clarification needed] to twelfth century, when scholasticism flourished it became approximated to its known linguistic origins[clarification needed] as Wirccester. The county later developed from the shire's name Wigornia from the Anglo-Norman period into the foundations of the Market Fairs during the Henrician and Edwardian parliaments (1216-1377). It was still known as County Wigorn in 1750[citation needed] when the Shire Courts were still divided into Hundreds.

The Weorgoran (the "people of the winding river")[citation needed] were precursors of Hwicce and probably the West Saxons who entered the area some time after the 577 Battle of Dyrham. In 680, their fort at Worcester was chosen—in preference to both the much larger Gloucester and the royal court at Winchcombe—to be the seat of a new bishopric, suggesting there was already a well-established and powerful Christian community when the site fell into English hands. The oldest known church was St Helen's, which was certainly British; the Saxon cathedral was dedicated to St Peter.[6]

Worcester appears frequently in the historic records prior to the Viking era, often with reference to the church and monastic communities, and showing evidence of extensive ecclesiastical ownership of lands. During King Alfred's reign, the earls of Mercia fortified Worcester "for the protection of all the people" at the request of Bishop Werfrith. It appears that maintenance of the defences was to be paid for by the townspeople. A unique document detailing this and privileges granted to the church also outlines the existence of Worcester's market and borough court, differentiation between church and market quarters within the city, as well as the role of the King in relation to the roads.[10]

Worcester's fortifications would most likely have established the line of the wall that was extant until the 1600s, perhaps excepting the south east area near the former castle. It is referred to as a wall by contemporaries, so may have been of stone.[10]

Oswald and Eadnoth

Worcester was a centre of monastic learning and church power. Oswald of Worcester was an important reformer, appointed Bishop in 961, jointly with York. The last Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, Wulfstan, or St Wulstan, was also an important reformer, and stayed in post until his death in 1095.

Worcester became the focus of tax resistance against the Danish Harthacanute. Two huscarls were killed in May 1041 while attempting to collect taxes for the expanded navy, after being driven into the Priory, where they were murdered. A military force was sent to deal with the non-payment, while the townspeople attempted to defend themselves by moving to and occupying the island of Bevere, two miles up river, where they were then besieged. After Harthacnut's men had sacked the city and set it alight, agreement was reached.[10]

Worcester was also the site of a mint during the late Anglo-Saxon period, with seven moneyers in the reign of Edward the Confessor. This implies a middling role in trade for the city.[10]

Medieval

Early medieval

Worcester was, for tax purposes, counted within[clarification needed] rural hundreds at the start of the Norman period. It was administratively independent.[10]

Worcester's growth and position as a market town distributing goods and produce came from its river crossing and bridge, and its position on the road network. In the 14th century, the nearest bridges over the Severn were at Gloucester and Bridgnorth. The main road from London to mid-Wales ran through Worcester. The road north west ran to Kidderminster, Bridgnorth and Shrewsbury; and the road north through Bromsgrove connected to Coventry, and towards Derby. The road southward connected to Tewkesbury and Gloucester.[10]

There had been a bridge in Worcester since at least the 11th century; it was replaced in the early 14th century. This bridge, situated below the current Newport Street, had six arches on piers with starlings, and the middle pier had a gatehouse.[10]

The city walls' upkeep was paid for by the residents. The walls included bastions and a watercourse. The course of the wall was fairly irregular. The entrances to the city were through defensive gates, constructed at different times, including St. Martin's Gate in the east, Sidbury Gate to the south, Friar Gate, Edgar Tower and Water Gate; there were six gates by the 16th century.[10]

The medieval cloisters

Worcester was also a centre of medieval religious life; there were several monasteries until the dissolution. These included the Greyfriars, Blackfriars, Penitent Sisters and the Benedictine Priory, now Worcester Cathedral.[11] Monastic houses provided hospitals and education, including Worcester School. The St. Wulstan Hospital was founded around 1085 and was dissolved with the monasteries in 1540. The St. Oswald Hospital was possibly founded by St Oswald. Substantial lands and property in Worcester were held by the church.[10]

Domesday Book also records a considerable number of town houses belonging to rural landowners, presumably used as residences while selling produce from their lands.[10]

In the 1100s, Worcester suffered a number of city fires. The first was on 19 June 1113, destroying town, castle and cathedral, and the second in November 1131.[10]

The following century, the town (then better defended) was attacked several times (in 1139, 1150 and 1151) during the Anarchy, i.e. civil war between King Stephen and Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I. The 1139 attack again resulted in fire and destruction of a portion of the city, with citizens being held for ransom.

Another fire in 1189 destroyed much of the city for the fourth time that century.[10]

Worcester received its first royal charter in 1189. This set out the annual payment made to the Crown as £24 per annum, and set out that the city would deal directly with the Crown's Exchequer, rather than through the county sheriff, who would no longer have general jurisdiction over the city. However, under King John, Worcester's charter was not renewed, which allowed him to levy increasing and arbitrary taxation (tallage) on Worcester, demanding £100 in 1214.

In 1227, under King Henry III Worcester regained its charter and was granted more freedoms. The annual tax was increased to £30. The sheriff was again removed from his role representing the city to the Crown, except in some limited circumstances. A guild of merchants was created, creating a trading monopoly for those admitted. Villeins who resided in the city for a year and day, and were members of the guild, were to be deemed free. The charter was renewed in 1264.[10] Worcester's institutions grew at a slower pace than most county towns and had detectably archaic echoes. It is likely that this is related to the power of the local aristocracy.[10]

Jewish life, persecution and expulsions

Worcester had a small Jewish population by the late 12th century. It was one of a number of places allowed to keep records of debts, in an official locked chest known as an archa. (An archa or arca (plural archae/arcae) was a municipal chest in which deeds were preserved.) [12] Jewish life probably centred around what is now Copenhagen Street.

The Diocese was notably hostile to the Jewish community in Worcester. Peter of Blois was commissioned by a Bishop of Worcester, probably John of Coutances, to write a significant anti-Judaic treatise Against the Perfidy of Jews around 1190.[13]

William de Blois, as Bishop of Worcester, imposed particularly strict rules on Jews within the diocese in 1219.[14] As elsewhere in England, Jews were officially compelled to wear square white badges, supposedly representing tabulae.[15] In most places, this requirement was relinquished as long as fines were paid. In addition to enforcing the church laws on wearing badges, Blois tried to impose additional restrictions on usury, and wrote to Pope Gregory in 1229 to ask for better enforcement of these and further, harsher measures, which the Papacy granted.[16]

A national assembly of Jewish notables was summoned to Worcester by the Crown in 1240 to assess their wealth for taxation; at which Henry III "squeezed the largest tallage of the thirteenth century from his Jewish subjects."[17]

In 1263 Worcester's Jewish residents were attacked by a baronial force led by Robert Earl Ferrers and Henry de Montfort. Most were killed.[10] Ferrers used this opportunity to remove the titles to his debts by taking the archae.[18] The massacre in Worcester was part of a wider campaign by Simon de Montfort's allies at the start of the Second Barons' War. A massacre of London's Jewry also took place during the war.

A few years later, in 1275, those still remaining in Worcester were forced to move to Hereford,[10] as Jews were expelled from towns under the jurisdiction of the queen mother.[19]

Late medieval

Worcester's Ordinances of the sixth year of Edward IV, renewed in 1496–7, and detailed in 82 clauses, give a detailed picture of life and city organisation in the late medieval period. They were to be enforced by the city's bailiffs. Chamberlains received and accounted for rents and other income and the use of common lands within Worcester was set out. Trade regulations covered bread and ale. Others dealt with sanitation, fire regulations and upkeep of the city wall, quays and pavements. Public order and crimes including affray are covered. Citizens were given the privilege of being imprisoned underneath the Guildhall rather than in the town jail, except for the most serious offences.[10]

The cloth industry was also regulated by the Ordinances. Apart from regulation of weights and measures, the ordinances also attempted to protect the artisans engaged in the trade. Payment in kind was banned, with fines of 20 shillings for anyone making payment other than with gold and silver. People were only to be employed if they lived in the city and its suburbs.[10]

Worcester elected members of Parliament at the Guildhall, by the loudest shouting rather than raising of hands. Members of Parliament had to own freehold property worth 40 shillings a year, and be "of good name and fame, not outlawed, not acombred in accyons as nygh as men may knowe, for worshipp of the seid cite".[20] Their wages were levied by the Constable.

The city council was organised by a system of co-option. There were 24 members of the high chamber, and 48 of the lower chamber. Committees appointed the two Bailiffs and made financial decisions, while the two chambers agreed the city's rules, or ordinances.[10]

By late medieval times the population had grown to 1,025 families, excluding the cathedral quarter, so probably stood under 10,000.[21] Worcester had grown beyond the limits of its walls with a number of suburbs.[10]

The manufacture of cloth and allied trades started to become a large local industry. For instance, Leland stated in the mid 1500s that "The welthe of the towne of Worcestar standithe most by draping, and noe towne of England, at this present tyme, maketh so many cloathes yearly as this towne doth."[22]

The glove-making trade has its roots in this period.[10]

Evolution of craft guilds

Through the medieval and early modern period, Worcester developed a system of craft guilds. Guilds regulated who could work in a trade, trade practices and training, and provided social support for members. The city's late medieval ordinances banned tilers from forming a guild, and encouraged tilers to settle in Worcester to trade freely. Roofs of thatch and wooden chimneys were banned in order to reduce fire risks.[10]

Early modern

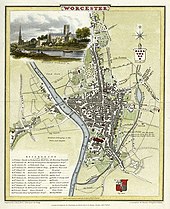

Worcester, 1610 map

The Dissolution saw the Priory's status change, as it lost its Benedictine monks. There were around 36 monks plus the Prior at dissolution in 1540 and some 16 were given pensions immediately or soon after, the rest being employed in the new Deanery. It was necessary to establish 'public schools' to replace monastic education in Worcester as elsewhere. This led to the establishment of King's School. Worcester School continued to teach. St Oswald's Hospital survived the dissolution, later providing almshouses;[23] the charity and its housing survives to the present.

The city was given the right to elect a Mayor and was designated a county corporate in 1621, giving it autonomy from local government. From this point, Worcester was governed by a mayor, recorder and six aldermen. Councillors were selected through co-option.[10]

Worcester in this period contained green spaces such as orchards and fields between its main streets within the city wall boundary, as evidenced by Speed's map of 1610. The walls were still more or less complete at this time, but suburbs had also been established beyond them.

Civil war

Battle of Worcester

Worcester equivocated about whether to support the Parliamentary cause before the outbreak of civil war in 1642, eventually siding with Parliament. The city was swiftly occupied by the Royalists, who billeted their troops in the city and used the cathedral to store munitions. Essex briefly retook the city for Parliament after the skirmish at the Battle of Powick Bridge, the first engagement of the war. Parliamentary troops then ransacked the cathedral building. Stained glass was smashed and the organ destroyed, along with library books and monuments.[24] Essex was soon forced to withdraw, after the Battle of Edgehill.

The city spent the rest of the war under Royalist occupation, as did the county, for the most part. Worcester was a garrison town and had to bear the expense of sustaining and billeting a large number of Royalist troops. During the Royalist occupation, the suburbs were destroyed to make defence easier. Responsibility for maintenance of defences was transferred to the military command. High taxation was imposed, and many male residents impressed into the army.[25]

As Royalist power collapsed in May 1646, Worcester was placed under siege. Worcester had around 5,000 civilians, together with a Royalist garrison of around 1,500 men, facing a 2,500-5,000 strong force of the New Model Army. Worcester finally surrendered on 23 July, bringing the first civil war to a close in Worcestershire.[26]

In 1651 a Scottish army, 16,000 strong, marched south along the west coast in support of Charles II's attempt to regain the Crown. When the army approached, Worcester's council voted to surrender, fearing further violence and destruction. The Parliamentary garrison withdrew to Evesham in the face of the overwhelming numbers against them. The Scots were billeted in and around the city, again at great expense and causing new anxiety for the residents. The Scots were joined by very limited local forces, including a company of 60 men under Francis Talbot.[27]

The Battle of Worcester (3 September 1651), took place in the fields a little to the west and south of the city, near the village of Powick. Charles II was easily defeated by Cromwell's forces of 30,000 men.[28] Charles II returned to his headquarters in what is now known as King Charles House in the Cornmarket,[29] before fleeing in disguise with Talbot's help[30] to Boscobel House in Shropshire, from where he eventually escaped to France. Worcester was heavily looted by the Parliamentarian army afterwards. The city council estimated £80,000 of damage was done, and the subsequent debts still not recovered into the 1670s.[31]

From 1646 to 1660, the bishopric was abolished and the cathedral fell into disrepair.

After the Restoration

After the Restoration in 1660, Worcester cleverly used its location as the site of the final battles of the First Civil War (1646) and Third Civil War (1651) to mount an appeal for compensation from the new King Charles II. As part of this and not based upon any historical fact, it invented the epithet Fidelis Civitas (The Faithful City) and this motto has since been incorporated into the city's coat of arms.[32][33]

Worcester Guildhall

Worcester Guildhall was rebuilt in 1721, replacing the earlier hall on the same site. The now Grade I listed Queen Anne style building was described by Pevsner as "a splendid town hall, as splendid as any of C18 England".[34]

Worcester's historic bridge was replaced, at a cost of £29,843 including its approaches, opening on 17 September 1781. As the town's population expanded, the green areas between the main streets filled with housing and back streets. Nevertheless, the size of the city and suburbs was roughly the same as it was in the early 1600s. Large stretches of the walls of the city had been removed by 1796.[10]

The Royal Worcester Porcelain Company factory was founded by Dr John Wall in 1751. However production ceased in 2009. A handful of decorators are still employed at the factory, and the museum on the site is still open to the public. Since 2015 there has been extensive re-development of the quarter, entirely devoted to housing.

Industrial revolution and Victorian

Map of Worcester in 1806

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Worcester was a major centre for glove making, employing nearly half the glovers in England at its peak (over 30,000 people).[35] In 1815 the Worcester and Birmingham Canal opened, allowing Worcester goods to be transported to a larger conurbation.

Riots took place in 1831, in response to the defeat of the Reform Bill, reflecting discontent with the city administration and the wider lack of democratic representation.[10] Riots occurred elsewhere, including Bristol. Local government reform took place in 1835, which for the first time created election procedures for councillors, but also restricted the ability of the city to buy and sell property, requiring Treasury permission.[10]

Up until 1835, the legal distinction between a select group of citizens with specific privileges and other residents of the town had survived.[10]

The British Medical Association (BMA) was founded in the Board Room of the old Worcester Royal Infirmary building in Castle Street in 1832.[36] While part of the Royal Infirmary has now been demolished to make way for the University of Worcester's new city campus, the original Georgian building has been preserved.[37] One of the old wards opened as a medical museum, the Infirmary, in 2012.[38][39]

Railways opened in Worcester in 1850, with Shrub Hill, jointly owned by the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway and Midland Railway, initially running to Birmingham only. Foregate Street was opened in 1860 by the Hereford and Worcester Railway, quickly incorporated into the West Midland Railway. The WMR lines became part of the Great Western Railway after 1 August 1863.

In 1882 Worcester hosted the Worcestershire Exhibition, inspired by the Great Exhibition in London. There were sections for exhibits of fine arts (over 600 paintings), historical manuscripts and industrial items. The profit was £1,867.9s.6d. The number of visitors is recorded as 222,807. Some of the profit from the exhibition was used to build the Victoria Institute in Foregate Street, Worcester. This was opened on 1 October 1896 and originally housed the city art gallery and museum; now located on Foregate Street.[citation needed]

Twentieth century to present

Rail reorganisation in 1922 saw the Midland Railway's routes from Shrub Hill absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.

During the Second World War, the city was chosen to be the seat of an evacuated government in case of mass German invasion. The War Cabinet, along with Winston Churchill and some 16,000 state workers, would have moved to Hindlip Hall (now part of the complex forming the Headquarters of West Mercia Police), 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Worcester and Parliament would have temporarily seated in Stratford-upon-Avon. The former RAF station RAF Worcester was located east of Northwick.[citation needed]

A fuel storage depot was constructed in 1941/2 by Shell Mex & BP (later operated by Texaco) for the government on the eastern bank of the River Severn, about one mile south of Worcester. There were six 4,000 ton semi-buried tanks for the storage of white oils. It had no rail or road loading facilities but distribution could be carried out by barge through the Diglis basin and the depot could receive fuel either by barge or the GPSS pipeline network. It was at one time used as a civil reserve storing gas oil and then stored aviation kerosene for USAFE. In the early 1990s it was closed down and was sold for housing in the 2000s.[40]

In the 1950s and 1960s large areas of the medieval centre of Worcester were demolished and rebuilt as a result of decisions by town planners. This was condemned by many such as Nikolaus Pevsner who described it as a "totally incomprehensible... act of self-mutilation".[41] There is still a significant area of medieval Worcester remaining, examples of which can be seen along City Walls Road, Friar Street and New Street, but it is a small fraction of what was present before the redevelopments.

The current city boundaries date from 1974, when the Local Government Act 1972 transferred the parishes of Warndon and St. Peter the Great County into the city.

Images

Tudor buildings in Friar Street |  Tudor building with jettied upper storey in New Street |  Worcester Shrub Hill railway station with a London Midland train. |

Governance

The Conservatives had a majority on the council from 2003 to 2007, when they lost a by-election to Labour meaning the council had no overall control.[42] The Conservatives remained with the most seats overall with 17 out of 35 seats after the 2008 election.[43]

The council currently has no overall control, but is under the leadership of Cllr Marc Bayliss (Conservative) and deputy leader Cllr Adrian Gregson (Labour).

Worcester has one member of Parliament, Robin Walker of the Conservative Party, who represents the Worcester constituency as of the May 2010 general election.[44]

The County of Worcestershire's local government arrangement is formed of a non-metropolitan county council (Worcestershire County Council) and six non-metropolitan district councils, with Worcester City Council being the district council for most of Worcester, with a small area of the St. Peters suburb actually falling within the neighbouring Wychavon District council. The Worcester City Council area includes two parish councils, these being Warndon Parish Council and St Peter the Great Parish Council.

Worcester Guildhall houses the local council and dates from 1721 (see history above).

Geography

Notable suburbs in Worcester include Barbourne, Blackpole, Cherry Orchard, Claines, Diglis, Northwick, Red Hill, Ronkswood, St Peter the Great (also simply known as St Peters), Tolladine, Warndon and Warndon Villages (which was once the largest housing development in the Country when the area was being constructed in the late 1980s/very early 1990s). Most of Worcester is on the eastern side of the River Severn; Henwick, Lower Wick, St. John's and Dines Green are on the western side.

Climate

Worcester enjoys a temperate climate with warm summers and mild winters generally. However, the city can experience more extreme weather and flooding is often a problem.[45] In 1670, the River Severn burst its banks and the subsequent flood was the worst ever seen by Worcester. The closest flood height to what is known as the Flood of 1670 was when the Severn flooded in the torrential rains of July 2007, which is recorded in the Diglis Basin.[46] And then again in 2014.[47]

During the winters of 2009-10 and 2010-11 the city experienced prolonged periods of sub-freezing temperatures and heavy snowfalls. In December 2010 the temperature dropped to −19.5 °C (−3.1 °F) in nearby Pershore.[48] The River Severn and the River Teme partially froze over in Worcester during this cold snap. In contrast, Worcester recorded 36.6 °C (97.9 °F) on 2 August 1990.[49] Between 1990 and 2003, weather data for the area was collected at Barbourne, Worcester. After the closure of this weather station, the nearest one is located at Pershore.[50]

| Climate data for Worcester | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.1 (62.8) | 19.6 (67.3) | 21.1 (70) | 26.6 (79.9) | 28.2 (82.8) | 33.1 (91.6) | 33.8 (92.8) | 36.6 (97.9) | 28.8 (83.8) | 28.4 (83.1) | 18.6 (65.5) | 17.6 (63.7) | 36.6 (97.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7 (45) | 8 (46) | 11 (52) | 14 (57) | 17 (63) | 20 (68) | 22 (72) | 22 (72) | 19 (66) | 15 (59) | 10 (50) | 8 (46) | 14 (58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) | 1 (34) | 3 (37) | 4 (39) | 7 (45) | 10 (50) | 12 (54) | 12 (54) | 10 (50) | 7 (45) | 4 (39) | 2 (36) | 6 (43) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.1 (6.6) | −12.7 (9.1) | −9.4 (15.1) | −7.3 (18.9) | −2.3 (27.9) | −1.0 (30.2) | 2.7 (36.9) | 3.6 (38.5) | −0.6 (30.9) | −5.1 (22.8) | −10.5 (13.1) | −19.5 (−3.1) | −19.5 (−3.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 53 (2.1) | 31 (1.2) | 31 (1.2) | 42 (1.7) | 47 (1.9) | 48 (1.9) | 50 (2) | 53 (2.1) | 48 (1.9) | 56 (2.2) | 54 (2.1) | 50 (2) | 563 (22.3) |

| Source #1: [51] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Barbourne and Pershore extremes (nearest stations)[50] | |||||||||||||

Skyline of Worcester viewed from Worcester Cathedral

Green belt

Worcester is within a green belt region that extends into the wider surrounding counties, and is in place to reduce urban sprawl between the cities and towns in the nearby West Midlands conurbations centred around Birmingham and Coventry, discouraging further convergence, protect the identity of outlying communities, encourage brownfield reuse, and preserve nearby countryside. This is achieved by restricting inappropriate development within the designated areas, and imposing stricter conditions on permitted building.[52]

Within the city boundary, there is a small extent of green belt north of the Worcester & Birmingham canal, and north of the Perdiswell and Northwick suburbs. This is part of a larger, isolated tract south of the main green belt that extends into the adjacent Wychavon district, minimising urban sprawl between Fernhill Heath and Droitwich Spa, and maintaining their separation. The green belt was first drawn up under Worcestershire County Council in 1975, and the size in the borough in 2017 amounted to some 240 hectares (2.4 km2; 0.93 sq mi).[53]

Demography and religion

The 2001 census[54] recorded Worcester's population at 93,353. About 96.5% of Worcester's population was white; of which 94.2% were White British,[55] greater than the national average.[56] The largest religious group are Christians, who made up 77% of the city's population.[57] People who reported having no religion or who did not state their religion made up 21% of the city's population. Other religions totaled less than 2% of the population. Ethnic minorities include people of Bangladeshi, Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Italian and Polish origin, with the largest single minority group being British Pakistanis, numbering around 1,200, approximately 1.3% of Worcester's population.[57]

Old St Martin's Church (Church of England)

This has led to Worcester containing a small but diverse range of religious groups; as well as the commanding Anglican Worcester Cathedral, there are also Catholic, United Reformed Church [58] and Baptist churches, a large centre for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), an Islamic mosque and a number of smaller interest groups regarding Eastern Religions such as Buddhism and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.[59]

Worcester is the seat of a Church of England bishop. His or her official signature is his or her Christian name followed by Wigorn. (an abbreviation for the Latin Wigorniensis, meaning 'of Worcester'),[60] which is also occasionally used as an abbreviation for the name of the county.

The Archdeacon of Worcester, inducted in November 2014, was Rector of St. Barnabas with Christ Church in Worcester for eight years.

Economy

The city of Worcester, located on the River Severn and with transport links to Birmingham and other parts of the Midlands through the vast canal network, became an important centre for many light industries. The late-Victorian period saw the growth of ironfounders, like Heenan & Froude, Hardy & Padmore and McKenzie & Holland.

Glove industry

Gloves, Worcester City Art Gallery & Museum

One of the flourishing industries of Worcester was glove making. Worcester's gloving industry peaked between 1790 and 1820 when about 30,000 were employed by 150 companies. At this time nearly half of the glove manufacturers of Britain were located in Worcestershire.

In the 19th century the industry declined because import taxes on foreign competitors, mainly from France, were greatly reduced. By the middle of the 20th century, only a few Worcester gloving companies survived since gloves became less fashionable and free trade allowed in cheaper imports from the Far East. Nevertheless, at least three large glove manufacturing companies survived until the late 20th century: Dent Allcroft, Fownes and Milore. Queen Elizabeth II's coronation gloves were designed by Emil Rich and manufactured in the Worcester-based Milore factory.[61][62]

Manufacturing

Lea & Perrins advertisement (1900)

The inter-war years saw the rapid growth of engineering, producing machine tools James Archdale, H.W. Ward, castings for the motor industry Worcester Windshields and Casements, mining machinery Mining Engineering Company (MECO) which later became part of Joy Mining Machinery and open-top cans Williamsons, though G H Williamson and Sons had become part of the Metal Box Co in 1930. Later the company became Carnaud Metal Box PLC.

Worcester Porcelain operated in Worcester until 2009, when the factory closed down due to the recession. However, the site of Worcester Porcelain still houses the Museum of Royal Worcester which is open daily to visitors.[63]

One of Worcester's most famous products, Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce is made and bottled at the Midland Road factory in Worcester, which has been the home of Lea & Perrins since 16 October 1897. Mr Lea and Mr Perrins originally met in a chemist's shop on the site of the now Debenham's store in the Crowngate Shopping Centre.

The surprising foundry heritage of the city is represented by Morganite Crucible[64] at Norton which produces graphitic shaped products and cements for use in the modern industry.

Worcester is the home of what is claimed to be the oldest newspaper in the world, Berrow's Worcester Journal, which traces its descent from a news-sheet that started publication in 1690. The city is also a major retail centre with several covered shopping centres that has most major chains represented as well as a host of independent shops and restaurants, particularly in Friar Street and New Street.

The city is home to the European manufacturing plant of Yamazaki Mazak Corporation, a global Japanese machine tool builder, which was established in 1980.[65]

Retail trade

The Kays mail order business was founded in Worcester in the 1880s and operated from numerous premises in the city until 2007. It was then bought out by Reality, owner of the Grattan catalogue. Kays' former warehouse building was demolished in 2008 and now is residential housing.[66]

Worcester's main shopping centre is the High Street, home to the stores of a number of major retail chains. Part of the High Street was modernised in 2005 amid much controversy and further modernised in 2015, with current redevelopment of Cathedral Plaza and Lychgate Shopping Centre. Many of the issues focused on the felling of old trees, the duration of the works (caused by the weather and an archaeological find) and the removal of flagstones outside the city's 18th century Guildhall.[67]

The other main thoroughfares are the Shambles and Broad Street, while the Cross (and its immediate surrounding area) is the city's financial centre and location of the majority of Worcester's main bank branches.

There are three main covered shopping centres in the city centre, these being CrownGate Shopping Centre, Cathedral Plaza and Reindeer Court. There is also an unenclosed shopping area located immediately east of the city centre called St. Martin's Quarter. There are three retail parks, the Elgar and Blackpole retail parks, which are located in the inner suburb of Blackpole and the Shrub Hill Retail Park neighbouring St. Martin's Quarter. Retailers such as ASDA, B & M and Aldi are all located within close proximity to St Martin's Quarter.

Landmarks

Worcester Cathedral at night.

The most famous landmark in Worcester is the imposing Anglican Worcester Cathedral. The current building, officially named the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary, was known as Worcester Priory before the English Reformation. Construction begun in 1084. Its crypt dates from the 10th century. The chapter house is the only circular one in the country. The cathedral also has the distinction of housing the tomb of King John.

Near the cathedral is the spire of St. Andrew's Church, also known as Glover's Needle; the rest of the church was demolished in 1949.[68]

The parish church of St. Helen, located on the north side of the High Street, is mainly medieval with a west tower rebuilt in 1813. The east end, refenestration and porch were completed by Frederick Preedy in 1857-63. There was further restoration, by Aston Webb, in 1879-80. It is a Grade II* listed building.[69]

The high-water mark from the flood of 1670, as well as more recent flood levels, are marked on a brass plate located on a wall adjacent to the path along the river leading to the cathedral.

Limited parts of Worcester's city wall remain in situ.

The Hive, situated on the northern side of the River Severn at the former cattle market site, is Worcester's joint public and university library and archive centre, heralded as "the first of its kind in Europe". It is a prominent landmark feature on the Worcester skyline. With seven towers and a golden rooftop, the Hive has gained recognition winning two international awards[70][71] for building design and sustainability.

There are three main parks in Worcester: Cripplegate Park, Gheluvelt Park and Fort Royal Park, the last being on the site of an English Civil War battle. In addition, there is a large open area known as Pitchcroft to the north of the city centre on the east bank of the River Severn. It is a public space except on days when it is used for horse racing.

Gheluvelt Park was opened as a memorial to the participation of the Worcestershire Regiment's 2nd Battalion in the Battle of Gheluvelt during the First World War.[72]

Statue of Edward Elgar.

The statue of Sir Edward Elgar, commissioned from Kenneth Potts and unveiled in 1981, stands at the end of Worcester High Street facing the cathedral, only yards from the original location of his father's music shop, which was demolished in the 1960s.[73] Elgar's birthplace is a short way from Worcester, in the village of Broadheath.

There are also two large woodlands in the city, Perry Wood and Nunnery Wood. They cover 12 hectares and 21 hectares respectively. Perry Wood is often said to be the place where Oliver Cromwell met and made a pact with the devil.[74] Nunnery Wood is an integral part of the adjacent and popular Worcester Woods Country Park, itself next door to County Hall on the east side of the city.

Transport

Road

Worcester Shrub Hill railway station.

The M5 Motorway runs north-south immediately to the east of the City and is accessed by Junction 6 (Worcester North) and Junction 7 (Worcester South). This makes the city easily accessible by car to most parts of the country, including London which is only 118 miles (190 km) using the A44 via the Cotswolds and M40. A faster journey to London is possible via the M5, M42 and M40 for an increased distance of 134 miles (216 km).

Several A roads pass through the city. The A449 road runs south-west to Malvern and north to Kidderminster. The A44 runs south-east to Evesham and west to Leominster and Aberystwyth and crosses Worcester Bridge. The A38 trunk road runs south to Tewkesbury and Gloucester and north-north-east to Droitwich and Bromsgrove and Birmingham. The A4103 goes west-south-west to Hereford. The A422 heads east to Alcester, branching from the A44 a mile east of the M5. The city is encompassed by a partial ring road (A4440) which is formed, rather inconsistently, by single and dual carriageways. The A4440 road provides a second road bridge across the Severn (Carrington Bridge) just west of the A4440-A38 junction. Carrington Bridge links the A38 from Worcester towards Gloucester with the A449 linking Worcester with Malvern.

Rail

Worcester locomotive depot 14 April 1959

Worcester has two stations, Worcester Foregate Street and Worcester Shrub Hill.

Worcester Foregate Street is located in the city centre, on Foregate Street. The line towards Great Malvern and Hereford, which is the Cotswold line, crosses Foregate Street on an arched cast-iron bridge which was remodelled by the Great Western Railway in 1908 with decorative cast-iron exterior serving no structural purpose.[75] Between Foregate Street and the St. John's area of the city, heading towards Malvern and Hereford, the line is elevated and travels along the Worcester viaduct which crosses over the River Severn.

Worcester Shrub Hill is located around one mile east of the city centre on Shrub Hill Road. The station is part of a loop line off the Birmingham to Gloucester railway, which forms part of today's Cross Country Route.

Alongside the Worcester Shrub Hill station, on Shrub Hill Road, was the Worcester Engine Works. The polychrome brick building was erected about 1864 and was probably designed by Thomas Dickson. The venture was not a success and only 84 locomotives were built and the works closed in 1871.[76] The chairman of the Worcester Engine Works was Alexander Clunes Sheriff.

Both stations frequently serve Birmingham via Droitwich Spa, then either lines being firstly via Kidderminster and Stourbridge into Birmingham Snow Hill and Birmingham Moor Street then onwards usually to Dorridge or Whitlocks End or secondly via Bromsgrove and University and Birmingham New Street these services are run by West Midlands Trains. From both stations train run to Pershore, Evesham and onto the Cotswolds, Oxford and London.[77]

Bus

The main operator of bus services in and around the city is First Midland Red. A few other smaller operators provide services in Worcester, including; Astons, DRM and LMS Travel. The terminus and interchange for many bus services in Worcester is Crowngate bus station located in the city centre.

The city formerly had two park and ride sites, one located off the A38 in Perdiswell (opened in 2001) and the other at Sixways Stadium next to the M5 (opened 2009). Worcestershire County Council voted to close both of them in 2014 as part of a cost-saving package of cutbacks to bus services.[78]

The park and ride service at Sixways Stadium has since been reinstated, with LMS Travel operating the W3 route to Worcestershire Royal Hospital. The route does not service Worcester's city centre bus station.[79]

Air

Worcester's nearest major airport is Birmingham Airport which is accessible by road and rail.

Gloucestershire Airport is approximately 25 miles away and provides General Aviation connections and scheduled services with Citywing to Jersey, the Isle of Man and Belfast.

Education

Worcester is home to the University of Worcester, which was awarded university status in 2005 by HM Privy Council. From 1997 to 2005 it was known as University College Worcester (UCW) and prior to 1997 it was known as Worcester College of Higher Education. From 2005 to 2010 it was the fastest growing university in the UK, more than doubling its student population. The university is also home to the independent Worcester Students Union institution. The city is also home to two colleges, Worcester Sixth Form College and Heart of Worcestershire College.

High schools

The high schools located in the city are Bishop Perowne CofE College, Blessed Edward Oldcorne Catholic College, Christopher Whitehead Language College, Tudor Grange Academy Worcester, Nunnery Wood High School and New College Worcester which caters for blind and partially sighted pupils from the ages of 11 to 18.

Independent schools

Worcester is also the seat of three independent schools. The Royal Grammar School, founded in 1291 and Alice Ottley School merged in 2007. The King's School was re-founded in 1541 under King Henry VIII. St Mary's School, a girls' Catholic school, was the only remaining single-sex independent school, but closed in July 2014. Other independent schools include the Independent Christian school, the River School in Fernhill Heath and New College Worcester for the blind and partially sighted.

Sport

Entrance to the Worcester King George's Field.

Worcester Warriors, an Aviva Premiership Rugby Union team who play at Sixways Stadium.

Worcestershire County Cricket Club whose home ground is New Road.

National League North football club Worcester City (The team currently plays at The Victoria Ground in Bromsgrove)- Worcester Hockey Club has teams entered in the West Hockey Leagues.[80]

- Worcester St Johns Cycling Club

Worcester Wolves, a professional basketball team in the British Basketball League who play at the Worcester Arena.

Worcester Racecourse is on an open area known as "Pitchcroft" on the east bank of the River Severn.- Worcester has King George's Field in memorial to King George V.

Worcester Rowing Club which is situated near the city centre on the River Severn.

University of Worcester Rowing Club which shares accommodation with Worcester Rowing Club.- Worcester Athletics Club who meet on Tuesdays and Thursdays at Nunnery Wood Sports Centre

- Black Pear Joggers, an inclusive running club based at Perdiswell Leisure Centre

- Worcester University Climbing and Mountaineering Club

- Worcester Dominies and Guild Cricket Club

Culture

Festivals and shows

Every three years Worcester becomes home to the Three Choirs Festival, which dates from the 18th century and is credited with being the oldest music festival in the British Isles. The location of the festival rotates each year between the Cathedral Cities of the Three Counties, Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester. Famous for its championing of English music, especially that of Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst, Worcester was host of the festival in July 2014.[81]

The Worcester Festival was established in 2003 by Chris Jaeger MBE. Held in August, the festival consists of a variety of music, theatre, cinema and workshops, as well as the already established Beer Festival, which runs as an event within the Worcester Festival.[82] Worcester Festival ends with a free firework display on the banks of the River Severn on the Monday of the August bank holiday. The Artistic Director of the Worcester Festival is now actor, director and writer, Ben Humphrey.[citation needed]

For one weekend the city plays host to the Worcester Music Festival. Now in its 8th year (2015) the festival comprises a weekend of original music performed by predominantly local bands and musicians. All performances are free and take place throughout the city centre: in bars, clubs, community buildings, churches and the central library. In 2010 the festival comprised 230 different acts. The 2015 festival will take place between 18 and 20 September.

Founded in 2012, the Worcester Film Festival, is all about placing Worcestershire on the film-making map and encouraging local people to get involved in making film. The first festival took place at the Hive and including screenings, workshops and talks.[83]

The Victorian-themed Christmas Fayre is a major source of tourism every December.[84]Elton John came to the Worcestershire Cricket Ground, New Road on Saturday 9 June 2006. Status Quo came to Sixways Stadium (Worcester Warriors) on Saturday 28 July 2007.

The CAMRA Worcester Beer, Cider and Perry Festival takes place for three days each August [85] and is held on Pitchcroft Race Course. This festival is the largest beer festival within the West Midlands and within the top 10 in the United Kingdom with attendances being around 14,000 people.[86]

2015 will see the first Worcester Canal Festival, held at Lansdowne Park from the 12 to 14 June, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Worcester & Birmingham Canal.

Arts and cinema

Huntingdon Hall

Famous 18th century actress Sarah Siddons made her acting début here at the Theatre Royal in Angel Street. Her sister, the novelist Ann Julia Kemble Hatton, otherwise known as Ann of Swansea, was born in the city.[87] Matilda Alice Powles, better known as Vesta Tilley, a leading male impersonator and music hall artiste was born in Worcester.[88]

In present-day Worcester the Swan Theatre[89] stages a mixture of professional touring and local amateur productions. It is also home to the Worcester Repertory Company. Past Artistic Directors of the Worcester Repertory Company (and by default the Swan Theatre) have included John Doyle and David Wood OBE. The company's (and theatre's) current Artistic Director is Chris Jaeger MBE.

A number of 'stars' started their careers in the Worcester Repertory Company and the Swan Theatre. Imelda Staunton, Sean Pertwee, Celia Imrie, Rufus Norris, Kevin Whately and Bonnie Langford were all actors with the Rep at the start of their careers. Directors too have made a name for themselves with Phyllida Lloyd starting her directorial career as an Associate Director under John Doyle, a position that is now filled by Ben Humphrey.

The Countess of Huntingdon's Hall is a historic church now used as venue for an eclectic range of musical and comedy performances.[89] Recent acts have included Van Morrison, Eddie Izzard, Jack Dee, Omid Djalili and Jason Manford.

The Marrs Bar is a venue for gigs and stand-up comedy.[90] Worcester has two multi-screen cinemas; a Vue Cinema complex located on Friar Street and an Odeon Cinema on Foregate Street – both of which were 3D-equipped by March 2010.

In the northern suburb of Northwick is the Art Deco Northwick Cinema. Built in 1938 it contains one of the only two remaining interiors in Britain designed by John Alexander (the original perspective drawings are still held by RIBA). It was a bingo hall from 1966 to 1982 and then empty until 1991; it was then run as a music venue until 1996 and was empty again until autumn 2006 when it became an antiques and lifestyle centre, owned by Grey's Interiors, who were previously located in the Tything.[91]

Worcester was home to electronic music producer and collaborator Mike Paradinas and his record label Planet Mu, until the label moved to London in 2007.[92]

Media

Newspapers

Berrow's Worcester Journal, claimed to be the world's oldest newspaper- Worcester News

- Worcester Observer

Radio Stations

- BBC Hereford & Worcester

- Free Radio

- Youthcomm Radio

- Heart FM

- Sunshine Radio

- Touch FM

In popular culture

The well-researched historical novel The Virgin in the Ice, part of Ellis Peters' The Cadfael Chronicles series, depicts Worcester at the time of the Anarchy. It begins with the words:

"It was early in November of 1139 that the tide of civil war, lately so sluggish and inactive, rose suddenly to wash over the city of Worcester, wash away half of its livestock, property and women and send all those of its inhabitants who could get away in time scurrying for their lives northwards away from the marauders". (These are mentioned as having arrived from Gloucester, leaving a long lasting legacy of bitterness between the two cities.)

Twinning and planned twinning

Worcester is twinned with the German city of Kleve, the Parisian commune of Le Vésinet and its larger American namesake Worcester, Massachusetts.[93]

In February 2009 Worcester City Council's Twinning Association began deliberating an application to twin Worcester with the Palestinian city of Gaza. Councillor Alan Amos introduced the application, which was passed at its first stage by a majority of 35-6.[94] The proposal was later rejected by the Executive Committee of the City of Worcester Twinning Association for lack of funding due to its present commitment to existing twinning projects.[95]

Notable people

Edward Elgar

In birth order:

Hannah Snell (1723–1792), famous for impersonating a man and enlisting in the Royal Marines, was born and brought up in Worcester.

Elizabeth Blower (c. 1757/63 – post-1816), novelist, poet and actress, was born and raised in Worcester.

Ann Hatton (1764–1838), writer of the Kemble family, was born in Worcester.

James White (1775–1820), founder of first advertising agency in 1800 in London, was born in Worcester.

John Mathew Gutch (1776–1861), journalist, lived with his second wife at Barbourne, a suburb north of Worcester, from 1823 until his death.

Jabez Allies (1787–1856) a Worcestershire folklorist and antiquarian lived at Lower Wick, now part of Worcester.

Sir Charles Hastings (1794–1866), British Medical Association founder, lived in Worcester for most of his life.

Revd Thomas Davis, a hymn-writer born in Worcester in 1804

Philip Henry Gosse, naturalist, was born in Worcester in 1810.

Mrs. Henry Wood (1814–1887), writer, was born in Worcester.

Alexander Clunes Sheriff (1816–1878), City Alderman, businessman and Liberal MP, grew up in Worcester.

Edward Leader Williams (1828–1910), designer of the Manchester Ship Canal, was born and brought up at Diglis House in Worcester.

Benjamin Williams Leader (1831–1923), brother of previous, landscape artist.- Sir Thomas Brock (1847–1922), sculptor, best known for the London Victoria Memorial, was born in Worcester in 1847. Worcestershire Royal Hospital is in a road named after him.

Vesta Tilley (1864–1952), music hall performer who adopted this stage name aged 11, was born in Worcester. She became a noted male impersonator.- Sir Edward Elgar, composer, was born in 1857 in Broadheath, just outside Worcester, and he lived in the city from the age of two. His father ran a music shop in High Street; a statue of Elgar stands near the original site. His early musical career was based around the city, and his first major work was commissioned for the Three Choirs Festival there.

William Morris, Lord Nuffield (1877–1963), founder of Morris Motors and philanthropist, spent the first three years in Worcester.

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy (1883–1929, "Woodbine Willy"), poet and author, was Vicar of St Paul's Church. As an army chaplain in the First World War he would hand out Woodbine cigarettes to men in the trenches.

Ernest Payne (1884–1961) was born in Worcester and rode for St Johns Cycling Club, winning a gold medal in team pursuit at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London.

Sheila Scott (1922–1988), aviator, was born in Worcester.

Louise Johnson (1940–2012), biochemist and protein crystallographer, was born in Worcester.[96]

Timothy Garden, Baron Garden (1944–2007), Air Marshal and Liberal Democrat politician, was born in Worcester.

Dave Mason (born 1946), musician, singer, songwriter and guitarist, was born in Worcester.

Lee Cornes (born 1951), comedian and actor known for television roles in Blackadder, The Young Ones and Bottom serieses, was born in Worcester.[citation needed]

David McGreavy (born 1951, the "Monster of Worcester"), lived and committed child murders in Worcester.

Stephen Dorrell (born 1952), English Conservative politician and government member, was born in Worcester.

Karl Hyde (born 1957), English musician, frontman of trance music group Underworld was born in Worcester.

Donncha O'Callaghan (born 1979), Irish Rugby Union player. Joined Worcester Warriors in 2015 from Munster Rugby Irish and British and Irish Lions International

Kit Harington (born 1986), actor, lived in Worcester attended The Chantry School and Worcester Sixth Form College. He plays the character Jon Snow in Game of Thrones.

See also

- List of Bishops of Worcester

- Worcester City Art Gallery & Museum

- Jewish Community of Worcester

Notes

^ See Watts 2004, p. 700 for the Anglo-Saxon name

References

^ The Elgar Trail. ELGAR. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ City of Worcester. "The First Settlers". Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005.

^ City of Worcester. "Vertis—The Roman Industrial Town, 1st–4th centuries A.D." Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005.

^ Roman Britain. "Vertis".

^ Pevsner & Brookes 2007, p. 14

^ ab City of Worcester. "The Late Roman and Post-Roman Settlement, 4th Century A.D.–A.D. 680". Worcester City Council (Worcester), 2005

^ Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

^ Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain" at Britannia. 2000.

^ Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. James Toovey (London), 1844.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaa Willis-Bund & Page 1924

^ Willis-Bund & Page 1971b, pp. 167–173

^ "ARCHA". Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 23 November 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ de Blois 1194, Lazare 1903

^ Vincent 1994, p. 217

^ "Jewish Badge". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ Vincent 1994, p. 209

^ Mundill 2002, pp. 58–60

^ Mundill 2002, p. 42

^ Mundill 2002, p. 23

^ Ordinances quoted Willis-Bund & Page 1924

^ See Green, in History of Worcester Volume ii

^ Quoted in Willis-Bund & Page 1924

^ Willis-Bund & Page 1971a, pp. 175–179

^ Atkin 2004, pp. 52–53

^ Atkin 2004

^ Atkin 2004, pp. 125–7

^ Atkin 2004, pp. 142–143

^ Atkin 2004, pp. 142–147

^ Atkin 2004, p. 146

^ Atkin 2004, p. 144

^ Atkin 2004, pp. 144–147

^ "Civic Heralrdy of England and Wales – Severn Valley and the Marches". civicheraldry.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Atkin 1998

^ Guildhall – Worcester – Worcestershire – England. British Listed Buildings. Retrieved on 2 August 2013.

^ "Worcester glove-making". BBC. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

^ "BMA – Our history". British Medical Association. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "University demolition work starts". BBC News. 3 January 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

^ "The Infirmary - University of Worcester". Worcester.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "History of Worcester Royal Infirmary to Be Brought Back to Life". University of Worcester. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Tim Whittle: Fuelling the Wars - PLUTO and the Secret Pipeline Network 1936 to 2015, published 2017, p. 223.

ISBN 9780992855468

^ The Buildings of England – Worcester, Penguin, 1968

^ Lauren Rogers (21 September 2007). "Beaten Tory Keeps A Low Profile". Worcester News.

^ "Election 2008 Worcester council". BBC News Online. 19 April 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

^ "Michael Foster: Electoral history and profile". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

^ "Extreme weather in Herefordshire and Worcestershire". BBC. 20 September 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

^ "Great Floods". Webbaviation.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

^ "Flooding". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

^ Hill, Amelia (20 December 2010). "Chill record: Worcester town Pershore encounters drop to -19C". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

^ "TORRO - British Weather Extremes: Daily Maximum Temperatures". Torro.org.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ ab "Climate United Kingdom - Climate data". Tutiempo.net. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "Records and Averages". Msn.com. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "SWJCS GREEN BELT REVIEW July 2010" (PDF). Swdevelopmentplan.org.

^ "Green belt statistics". Gov.uk.

^ "Census 2001 – Profiles – Worcester". Statistics.gov.uk. 13 February 2003. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

^ "Worcester Town Profile" (PDF). Worcestershire.whub.org.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "National Statistics Online – Population Size". Statistics.gov.uk. 8 January 2004. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

^ ab "Census 2001 – Profiles – Worcester". Statistics.gov.uk. 13 February 2003. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

^ "Worcester United Reformed Church". Worcester United Reformed Church. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "The 'Hare Krishna' movement". BBC Hereford & Worcester. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Chambers Dictionary, 12th edition.

^ "Spirit of Enterprise Exhibition – Glove Making". Worcester Museums and Galleries.

^ Michael Grundy (21 June 2010). "This week in 1980". Worcester News. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Worcester Porcelain Museum". Worcester Porcelain Museum. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

^ Morganite Crucible Archived 1 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Mazak History". Yamazaki Mazak Corporation. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

^ "Kays Heritage Group". Kays Heritage Group. 19 May 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "At least £500000 to be pumped into sprucing up Worcester City Centre". Worcester News. December 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

^ Jones, Kath (2006). Keep right on to the end of the road. Cambridge: Vanguard. p. 68. ISBN 9781843862857.

^ "Church of St Helen, Worcester, Worcestershire". British Listed Buildings.

^ "National Sustainability Award". Thehiveworcester.org. June 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "CIBSE Building Performance Awards". Thehiveworcester.org. 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "Worcester's Gheluvelt Park given listed status". Bbc.co.uk. 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

^ "The Elgar Route – A walk around Elgar's Worcester" (PDF). Visitworcestershire.org.no 10, the Elgar Brothers’ music shop. Its location is commemorated in a plaque on a shop front unveiled in 2003.

^ Fraser, Antonia (1973). Cromwell Our Chief of Men. p. 387. ISBN 0-09-942756-7.

^ Richard Morriss The Archaeology of Railways, 1999 Tempus Publishing, Stroud. p89

^ Richard Morriss The Archaeology of Railways, 1999 Tempus Publishing, Stroud. Plate 93 p147

^ "Travelling to Worcestershire". Visit Worcestershire. Herefordshire and Worcestershire Chamber of Commerce. 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

^ County council leadership votes through park and ride axe, Worcester News, 10 June 2014.

^ "Worcester Park and Ride". Worcestershire County Council. 2016.

^ "Worcester Hockey Club". Worcesterhockey.co.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

^ "Three Choirs Festival – Programme & Tickets". 3choirs.org. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

^ "Worcester Festival". Worcesterfestival.co.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

^ 'New talent to shine' Worcester Standard. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

^ "Worcester's Victorian Christmas Fayre". Worcester News. 28 November 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

^ "2012 Worcester Beer, Cider and Perry Festival". Worcester Beer, Cider and Perry Festival. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ James Connell (15 August 2011). "Cheers! Beer festival is the biggest and best yet". Worcester News. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Ann Julia Kemble Hatton (1764-1848)". Literary Heritage West Midlands. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ Maitland, Sarah (1986). Vesta Tilley. London, UK: Virago Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-86068-795-3.

^ ab "About Us Worcester Live". Worcester Live. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Marr's Bar". Marr's Bar. 30 August 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

^ "Royal Institute of British Architects". Royal Institute of British Architects. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

^ "Planet MU Records Limited". Companies House. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

^ Lauren Rogers (31 January 2008). "City to fight US twin 'snub'". Worcester News.

^ Richard Vernalls (26 February 2009). "Worcester could be twinned with Gaza City". Worcester News. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

^ James Connell (10 March 2009). "Gaza twinning the decision is in". Worcester News. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

^ Garman, Elspeth F. (7 January 2016). "Johnson, Dame Louise Napier (1940–2012), biophysicist and structural biologist". Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/105683. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

General Worcester sources

Willis-Bund, J W; Page, William, eds. (1971a). "Hospitals: Worcester". A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 2. London: British History Online. pp. 175–179. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

Willis-Bund, J W; Page, William, eds. (1971b). "Friaries: Worcester". A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 2. London: British History Online. pp. 167–173. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

Willis-Bund, J W; Page, William, eds. (1924). "The city of Worcester: Introduction and borough". A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 4. London: British History Online. pp. 376–390. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

Pevsner, Nikolaus; Brookes, Alan (2007), "Worcester", Worcestershire, The Buildings of England (Revised ed.), London: Yale University Press, pp. 669–778, ISBN 9780300112986, OL 10319229M

Tuberville, T. C. (1852), Worcestershire in the nineteenth century., London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, LCCN 03006251, OCLC 9095242, OL 7063181M

Sources: Medieval history

Baker, Nigel; Holt, Richard (1996). "The City of Worcester in the Tenth Century". In Brooks, Nicholas; Cubitt, Catherine. St. Oswald of Worcester : Life and Influence. London, UK: Leicester University Press. ISBN 9780567340313.

Vincent, Nicholas (1994). "Two Papal Letters on the Wearing of the Jewish Badge, 1221 and 1229". 34: 209–24. JSTOR 29779960.

Mundill, Robin R (2002). England's Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262-1290. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52026-3.

de Blois, Peter (1194). "Against the Perfidy of the Jews". Medieval Sourcebook. University of Fordham.A treatise addressed to John Bishop of Worcester, probably John of Coutances who held that See, 1194-8.

Lazare, Bernard (1903), Antisemitism, its history and causes., New York: The International library publishing co., LCCN 03015369, OCLC 3055229, OL 7137045M

Sources: Civil War

Atkin, Malcolm (1998). Cromwell's Crowning Mercy: The Battle of Worcester 1651. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 0-7509-1888-8. OL 478350M.

Atkin, Malcolm (2004). Worcestershire under arms. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-84415-072-0. OL 11908594M.

General sources

Watts, Victor Ernest, ed. (2004). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107196896.

Further reading

John Britton; et al. (1814), "City of Worcester", Worcestershire, Beauties of England and Wales, 15, London: J. Harris

"Worcester", Black's Picturesque Tourist and Road-book of England and Wales (3rd ed.), Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1853

"Worcester", Great Britain (4th ed.), Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1897, OCLC 6430424

External links

![]() Media related to Worcester at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Worcester at Wikimedia Commons

Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Worcester. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Worcester. |

- Worcester City Council

- History of the City of Worcester

Worcester at Curlie