Ashkelon

Ashkelon

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | ʔašqlon |

| • Translit. | Ashkelon |

| • Also spelled | Ashqelon, Ascalon (unofficial) |

| |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Ashkelon | |

| Coordinates: 31°40′N 34°34′E / 31.667°N 34.567°E / 31.667; 34.567Coordinates: 31°40′N 34°34′E / 31.667°N 34.567°E / 31.667; 34.567 | |

| Country | |

| District | Southern |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Itamar Shimoni |

| Area | |

| • Total | 47,788 dunams (47.788 km2 or 18.451 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 137,945 |

| • Density | 2,900/km2 (7,500/sq mi) |

| Website | www.ashkelon.muni.il |

Ashkelon or Ashqelon (/ˈæʃkəlɒn/; Hebrew: ![]() אַשְׁקְלוֹן, [aʃkeˈlon]), also known as Ascalon (/ˈæskəlɒn/; Greek: Ἀσκάλων, Askálōn; Arabic: عَسْقَلَان, ʿAsqalān), is a coastal city in the Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean coast, 50 kilometres (31 mi) south of Tel Aviv, and 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) north of the border with the Gaza Strip. The ancient seaport of Ashkelon dates back to the Neolithic Age. In the course of its history, it has been ruled by the Ancient Egyptians, the Canaanites, the Philistines, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, the Phoenicians, the Hasmoneans, the Romans, the Persians, the Arabs and the Crusaders, until it was destroyed by the Mamluks in 1270.

אַשְׁקְלוֹן, [aʃkeˈlon]), also known as Ascalon (/ˈæskəlɒn/; Greek: Ἀσκάλων, Askálōn; Arabic: عَسْقَلَان, ʿAsqalān), is a coastal city in the Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean coast, 50 kilometres (31 mi) south of Tel Aviv, and 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) north of the border with the Gaza Strip. The ancient seaport of Ashkelon dates back to the Neolithic Age. In the course of its history, it has been ruled by the Ancient Egyptians, the Canaanites, the Philistines, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, the Phoenicians, the Hasmoneans, the Romans, the Persians, the Arabs and the Crusaders, until it was destroyed by the Mamluks in 1270.

The Arab village of al-Majdal or al-Majdal Asqalan (Arabic: المجدل; Hebrew: אל-מג'דל, מגדל) was established a few kilometres inland from the ancient site by the late 15th century, under Ottoman rule. In 1918, it became part of the British Occupied Enemy Territory Administration and in 1920 became part of Mandatory Palestine. Al-Majdal on the eve of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War had 10,000 Arab inhabitants and in October 1948, the city accommodated thousands more refugees from nearby villages.[2] Al-Majdal was the forward position of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force based in Gaza.[3] The village was conquered by Israeli forces on 5 November 1948, by which time most of the Arab population had fled,[4] leaving some 2,700 inhabitants, of which 500 were deported by Israeli soldiers in December 1948.[4] The town was initially named Migdal Gaza, Migdal Gad and Migdal Ashkelon by the new Jewish inhabitants. Most of the remaining Arabs were deported by 1950.

In 1953, the nearby neighborhood of Afridar was incorporated and the name "Ashkelon" was readopted to the town. By 1961, Ashkelon was ranked 18th among Israeli urban centers with a population of 24,000.[5] In 2017 the population of Ashkelon was 137,945.[1]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Neolithic era

2.2 Canaanite settlement

2.3 Philistine settlement

2.4 Classical period

2.5 Byzantine period

2.6 Crusader era

2.7 Islamic era

2.8 Ottoman and Mandate eras

2.9 State of Israel

3 Urban development

4 Economy

5 Education

6 Landmarks

6.1 Ashkelon National Park

7 Health care

8 Demographics

9 Culture and sports

10 Photos

11 Twin towns – sister cities

12 Notable residents

13 See also

14 References

14.1 Citations

14.2 Bibliography

15 External links

Etymology

The name Ashkelon is probably western Semitic, and might be connected to the triliteral root š-q-l ("to weigh" from a Semitic root ṯql, akin to Hebrew šāqal שָקַל or Arabic θiql ثِقْل "weight") perhaps attesting to its importance as a center for mercantile activities. Its name appeared in Phoenician and Punic as ŠQLN (𐤔𐤒𐤋𐤍) and ʾŠQLN (𐤀𐤔𐤒𐤋𐤍).[6]Scallion and shallot are derived from Ascalonia, the Latin name for Ashkelon.[7][8]

History

Ashkelon was the oldest and largest seaport in Canaan, part of the pentapolis (a grouping of five cities) of the Philistines, north of Gaza and south of Jaffa.

Neolithic era

Archaeological site with artifacts from the Neolithic era

The Neolithic site of Ashkelon is located on the Mediterranean coast, 1.5 km (0.93 mi) north of Tel Ashkelon. It is dated by Radiocarbon dating to c. 7900 bp (uncalibrated), to the poorly known Pre-Pottery Neolithic C phase of the Neolithic. It was discovered and excavated in 1954 by French archaeologist Jean Perrot. In 1997–1998, a large scale salvage project was conducted at the site by Yosef Garfinkel on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and nearly 1,000 square metres (11,000 sq ft) were examined. A final excavation report was published in 2008.

In the site over a hundred fireplaces and hearths were found and numerous pits, but no solid architecture, except for one wall. Various phases of occupation were found, one atop the other, with sterile layers of sea sand between them. This indicates that the site was occupied on a seasonal basis.

Ashkelon Pre-Pottery Neolithic C flint arrowheads

The main finds were enormous quantities of c. 100,000 animal bones and c. 20,000 flint artifacts. Usually at Neolithic sites flints far outnumber animal bones. The bones belong to domesticated and non-domesticated animals. When all aspects of this site are taken into account, it appears to have been used by pastoral nomads for meat processing. The nearby sea could supply salt necessary for the conservation of meat.

Canaanite settlement

Restored Canaanite city gate of Ashkelon[9] (2014)

Ashqelon as mentioned on Merneptah Stele: it reads <jsq3rwny> /'Asqaluni/ (with two determinatives)

The city was originally built on a sandstone outcropping and has a good underground water supply. It was relatively large as an ancient city with as many as 15,000 people living inside the walls. Ashkelon was a thriving Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BC) city of more than 150 acres (61 ha). Its commanding ramparts, measuring 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long, 50 feet (15 m) high and 150 feet (46 m) thick,[citation needed], and even as a ruin they stand two stories high. The thickness of the walls was so great that the mudbrick city gate had a stone-lined, 8 feet (2.4 m) wide tunnel-like barrel vault, coated with white plaster, to support the superstructure: it is the oldest such vault ever found.[9] Later Roman and Islamic fortifications, faced with stone, followed the same footprint, a vast semicircle protecting Ashkelon on the land side. On the sea it was defended by a high natural bluff. A roadway more than 20 feet (6.1 m) in width ascended the rampart from the harbor and entered a gate at the top.

In 1991 the ruins of a small ceramic tabernacle was found a finely cast bronze statuette of a bull calf, originally silvered, 4 inches (10 cm) long. Images of calves and bulls were associated with the worship of the Canaanite gods El and Baal.

Ashkelon is mentioned in the Egyptian Execration Texts of the 11th dynasty as "Asqanu."[10] In the Amarna letters (c. 1350 BC), there are seven letters to and from Ashkelon's (Ašqaluna) king Yidya, and the Egyptian pharaoh. One letter from the pharaoh to Yidya was discovered in the early 1900s.

Philistine settlement

The Philistines conquered Canaanite Ashkelon about 1150 BC. Their earliest pottery, types of structures and inscriptions are similar to the early Greek urbanised centre at Mycenae in mainland Greece, adding weight to the hypothesis that the Philistines were one of the populations among the "Sea Peoples" that upset cultures throughout the eastern Mediterranean at that time.

Ashkelon became one of the five Philistine cities that were constantly warring with the Israelites and the Kingdom of Judah. According to Herodotus, its temple of Venus was the oldest of its kind, imitated even in Cyprus, and he mentions that this temple was pillaged by marauding Scythians during the time of their sway over the Medes (653–625 BC). As it was the last of the Philistine cities to hold out against Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. When it fell in 604 BC, burnt and destroyed and its people taken into exile, the Philistine era was over.[citation needed]

Classical period

Ancient sarcophagus in Ashkelon

Ashkelon was soon rebuilt. Until the conquest of Alexander the Great, Ashkelon's inhabitants were influenced by the dominant Persian culture. It is in this archaeological layer that excavations have found dog burials. It is believed the dogs may have had a sacred role, however evidence is not conclusive. After the conquest of Alexander in the 4th century BC, Ashkelon was an important free city and Hellenistic seaport.

It had mostly friendly relations with the Hasmonean kingdom and Herodian kingdom of Judea, in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. In a significant case of an early witch-hunt, during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra, the court of Simeon ben Shetach sentenced to death eighty women in Ashkelon who had been charged with sorcery.[11]Herod the Great, who became a client king of Rome over Judea and its surrounds in 30 BC, had not received Ashkelon, yet he built monumental buildings there: bath houses, elaborate fountains and large colonnades.[12][13] A discredited tradition suggests Ashkelon has been his birthplace.[14] In 6 CE, when a Roman imperial province was set in Judea, overseen by a lower-rank governor, Ashkelon was moved directly to the higher jurisdiction of the governor of Syria province.

The city remained loyal to Rome during the Great Revolt, 66–70 AD.

Byzantine period

The city of Ascalon appears on a fragment of the 6th century AD Madaba Map.[15]

The bishops of Ascalon whose names are known include Sabinus, who was at the First Council of Nicaea in 325, and his immediate successor, Epiphanius. Auxentius took part in the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Jobinus in a synod held in Lydda in 415, Leontius in both the Robber Council of Ephesus in 449 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Bishop Dionysius, who represented Ascalon at a synod in Jerusalem in 536, was on another occasion called upon to pronounce on the validity of a baptism with sand in waterless desert and sent the person to be baptized in water.[16][17]

No longer a residential bishopric, Ascalon is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[18]

Crusader era

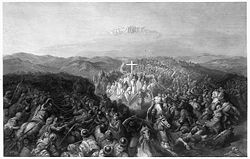

Battle of Ascalon, 1099

During the Crusades, Ashkelon (known to the Crusaders as Ascalon) was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), an Egyptian Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade. Until 1153, the Fatimids were able to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem from Ashkelon, which meant that the southern border of the Crusader States was constantly unstable. In response to these incursions into Outremer, King Fulk of Jerusalem constructed a number of Christian settlements around the city during the 1130s, in order to neutralise the threat of the Muslim garrison. In 1148, during the Second Crusade, the city was unsuccessfully besieged for eight days by a small Crusader army that was not fully supported by the Crusader States.

In 1150, the Fatimids fortified the city with 53 towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress.[19] Three years later, after a five-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. It was then added to the County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Jewish community in Ashkelon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives.

A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ashkelon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.[20]

Islamic era

Muslim pilgrims to the Shrine of Seyid Hussein, April 1943.

In 1187, Saladin took Ashkelon as part of his conquest of the Crusader States following the Battle of Hattin. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Saladin demolished the city because of its potential strategic importance to the Christians, but the leader of the Crusade, King Richard I of England, constructed a citadel upon the ruins. Ashkelon subsequently remained part of the diminished territories of Outremer throughout most of the 13th century and Richard, Earl of Cornwall reconstructed and refortified the citadel during 1240–41, as part of the Crusader policy of improving the defences of coastal sites. The Egyptians retook Ashkelon in 1247 during As-Salih Ayyub's conflict with the Crusader States and the city was returned to Muslim rule. The Mamluk dynasty came into power in Egypt in 1250 and the ancient and medieval history of Ashkelon was brought to an end in 1270, when the Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed. As a result of this destruction, the site was abandoned by its inhabitants and fell into disuse.

According to Shiite tradition, the head of Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Mohammad, was buried in Ashkelon. In the late 11th century it was moved to a new shrine named Mashad Nabi Hussein (or Sabni Hussein) built for the purpose. In 1153, at the time of the Crusaders' conquest of Ashkelon, the head was moved to Fustat (Egypt). The shrine was described as the most magnificent building in Ashkelon.[21] In the British Mandate period it was a "large maqam on top of a hill" with no tomb, but a fragment of a pillar showing the place where the head had been buried.[22] In July 1950, the shrine was destroyed at the instructions of Moshe Dayan in accordance with a 1950s Israeli policy of erasing Muslim historical sites within Israel.[23]

Ottoman and Mandate eras

High-rise residential development along the beach

Ashkelon Marina

The Arab village of Majdal was mentioned by historians and tourists at the end of the 15th century.[24] In 1596, Ottoman records showed Majdal to be a large village of 559 Muslim households, making it the 7th most populous locality in Palestine after Safad, Jerusalem, Gaza, Nablus, Hebron and Kafr Kanna.[25][26]

An official Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that Medschdel had a total of 420 houses and a population of 1175, though the population count included men only.[27][28]

The census of 1931 found 6,166 Muslims and 41 Christians living there.[29] By 1948, the population had grown to about 11,000.

Majdal was especially known for its weaving industry.[30] The town had around 500 looms in 1909. In 1920 a British Government report estimated that there were 550 cotton looms in the town with an annual output worth 30-40,000,000 Francs.[31] But the industry suffered from imports from Europe and by 1927 only 119 weaving establishments remained. The three major fabrics produced were "malak" (silk), 'ikhdari' (bands of red and green) and 'jiljileh' (dark red bands). These were used for festival dresses throughout Southern Palestine. Many other fabrics were produced, some with poetic names such as ji'nneh u nar ("heaven and hell"), nasheq rohoh ("breath of the soul") and abu mitayn ("father of two hundred").[32]

Majdal. Survey of Palestine. 1945. Scale 1:250,000

State of Israel

During the 1948 war, the Egyptian army occupied a large part of Gaza including Majdal. Over the next few months, the town was subjected to Israeli air-raids and shelling.[4] All but about 1,000 of the town's residents were forced to leave by the time it was captured by Israeli forces as a sequel to Operation Yoav on 4 November 1948.[4] General Yigal Allon ordered the expulsion of the remaining Palestinians but the local commanders did not do so and the Arab population soon recovered to more than 2,500 due mostly to refugees slipping back and also due to the transfer of Palestinians from nearby villages.[4][24] Most of them were elderly, women, or children.[24] During the next year or so, the Palestinians were held in a confined area surrounded by barbed wire, which became commonly known as the "ghetto".[5][24][33]Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion were in favor of expulsion, while Mapam and the Israeli labor union Histadrut objected.[4] The government offered the Palestinians positive inducements to leave, including a favorable currency exchange, but also caused panic through night-time raids.[4] The first group was deported to the Gaza Strip by truck on 17 August 1950 after an expulsion order had been served.[34] The deportation was approved by Ben-Gurion and Dayan over the objections of Pinhas Lavon, secretary-general of the Histadrut, who envisioned the town as a productive example of equal opportunity.[35] By October 1950, 20 Palestinian families remained, most of whom later moved to Lydda or Gaza.[4] According to Israeli records, in total 2,333 Palestinians were transferred to the Gaza Strip, 60 to Jordan, 302 to other towns in Israel, and a small number remained in Ashkelon.[24] Lavon argued that this operation dissipated "the last shred of trust the Arabs had in Israel, the sincerity of the State's declarations on democracy and civil equality, and the last remnant of confidence the Arab workers had in the Histadrut."[35] Acting on an Egyptian complaint, the Egyptian-Israel Mixed Armistice Commission ruled that the Palestinians transferred from Majdal should be returned to Israel, but this was not done.[36]

Ashkelon was formally granted to Israel in the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Re-population of the recently vacated Arab dwellings by Jews had been official policy since at least December 1948, but the process began slowly.[5] The Israeli national plan of June 1949 designated al-Majdal as the site for a regional urban center of 20,000 people.[5] From July 1949, new immigrants and demobilized soldiers moved to the new town, increasing the Jewish population to 2,500 within six months.[5] These early immigrants were mostly from Yemen, North Africa, and Europe.[37] During 1949, the town was renamed Migdal Gaza, and then Migdal Gad. Soon afterwards it became Migdal Ashkelon. The city began to expand as the population grew. In 1951, the neighborhood of Afridar was established for Jewish immigrants from South Africa,[38] and in 1953 it was incorporated into the city. The current name Ashkelon was adopted and the town was granted local council status in 1953. In 1955, Ashkelon had more than 16,000 residents. By 1961, Ashkelon ranked 18th among Israeli urban centers with a population of 24,000.[5] This grew to 43,000 in 1972 and 53,000 in 1983. In 2005, the population was more than 106,000.

On 1–2 March 2008, rockets fired by Hamas from the Gaza Strip (some of them Grad rockets) hit Ashkelon, wounding seven, and causing property damage. Mayor Roni Mahatzri stated that "This is a state of war, I know no other definition for it. If it lasts a week or two, we can handle that, but we have no intention of allowing this to become part of our daily routine."[39] In March 2008, 230 buildings and 30 cars were damaged by rocket fire on Ashkelon.[40]

On 12 May 2008, a rocket fired from the northern Gazan city of Beit Lahiya hit a shopping mall in southern Ashkelon, causing significant structural damage. According to The Jerusalem Post, four people were seriously injured and 87 were treated for shock. 15 people suffered minor to moderate injuries as a result of the collapsed structure. Southern District Police chief Uri Bar-Lev believed the Grad-model Katyusha rocket was manufactured in Iran.[41]

In March 2009, a Qassam rocket hit a school, destroying classrooms and injuring two people.[42]

In July 2010, a Grad rocket hit a residential area in Ashkelon, damaging nearby cars and an apartment complex.[43] In November 2014, the mayor, Itamar Shimoni, began a policy of discrimination against Arab workers, refusing to allow them to work on city projects to build bomb shelters for children. His discriminatory actions brought criticism from others, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat who likened the discrimination to the anti-Semitism experienced by Jews in Europe 70 years earlier.[44][45]

Ashkelon is located in the 20–30 seconds run to safety area due to grad rocket range

Urban development

Holiday Inn and 13th-century tomb of Sheikh Awad

In 1949 and 1950, three immigrant transit camps (ma'abarot) were established alongside Majdal (renamed Migdal) for Jewish refugees from Arab countries, Romania and Poland. Northwest of Migdal and the immigrant camps, on the lands of the depopulated Palestinian village al-Jura,[46] entrepreneur Zvi Segal, one of the signatories of Israel's Declaration of Independence, established the upscale Barnea neighborhood.[47]

A large tract of land south of Barnea was handed over to the trusteeship of the South African Zionist Federation, which established the neighborhood of Afridar. Plans for the city were drawn up in South Africa according to the garden city model. Migdal was surrounded by a broad ring of orchards. Barnea developed slowly, but Afridar grew rapidly. The first homes, built in 1951, were inhabited by new Jewish immigrants from South Africa and South America, with some native-born Israelis. The first public housing project for residents of the transit camps, the Southern Hills Project (Hageva'ot Hadromiyot) or Zion Hill (Givat Zion), was built in 1952.[47]

Under a plan signed in October 2015, seven new neighborhoods comprising 32,000 housing units, a new stretch of highway, and three new highway interchanges will be built, turning Ashkelon into the sixth-largest city in Israel.[48]

Economy

Ashkelon is the northern terminus for the Trans-Israel pipeline, which brings petroleum products from Eilat to an oil terminal at the port. The Ashkelon seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination plant is the largest in the world.[49][50] The project was developed as a BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer) by a consortium of three international companies: Veolia water, IDE Technologies and Elran.[51] In March 2006, it was voted "Desalination Plant of the Year" in the Global Water Awards.[52]

Since 1992, Israel Beer Breweries has been operating in Ashkelon, brewing Carlsberg and Tuborg beer for the Israeli market. The brewery is owned by the Central Bottling Company, which has also held the Israeli franchise for Coca-Cola products since 1968.[53]

Arak Ashkelon, a local brand of arak, is operating since 1925 and distributed throughout Israel.

Education

Ashkelon Academic College

The city has 19 elementary schools, and nine junior high and high schools. The Ashkelon Academic College opened in 1998, and now hosts thousands of students. Harvard University operates an archaeological summer school program in Ashkelon.[54]

Landmarks

Ashkelon marina breakwater

Ashkelon Khan and Museum contains archaeological finds, among them a replica of Ashkelon's Canaanite silver calf, whose discovery was reported on the front page of The New York Times.[55]

The Outdoor Museum near the municipal cultural center displays two Roman burial coffins made of marble depicting battle and hunting scenes, and famous mythological scenes.[55]

The remains of a 4th-century Byzantine church with marble slab flooring and glass mosaic walls can be seen in the Barnea Quarter.[55] Remains of a synagogue from this period have also been found.[56] A domed structure housing the 13th-century tomb of Sheikh Awad sits atop a hill overlooking Ashkelon's northern beaches.[57] A Roman burial tomb two kilometers north of Ashkelon Park was discovered in 1937. There are two burial tombs, a painted Hellenistic cave and a Roman cave. The Hellenistic cave is decorated with paintings of nymphs, water scenes, mythological figures and animals.[55]

There was an 11th-century mosque, Maqam al-Nabi Hussein, a site of pilgrimage by both Sunnis and Shiites, which had been built under the Fatimids by Badrul’jamali and where tradition held that the head of Mohammad's grandson Hussein ibn Ali was buried, was blown up by the IDF under instructions from Moshe Dayan as part of a broader programme to destroy mosques in July 1950.[58] The area was subsequently redeveloped for a local Israeli hospital, Barzilai. When his remains were later discovered on the hospital grounds, funds from the Shi'ite Ismaili sect in India were used to construct a marble prayer area, and it is visited by Shiite pilgrims from India and Pakistan.[58][59]

In 1986 ruins of 4th- to 6th-century baths were found in Ashkelon. The bath houses are believed to have been used for prostitution. The remains of nearly 100 mostly male infants were found in a sewer under the bathhouse, leading to conjectures that prostitutes had discarded their unwanted newborns there.[60] The Ashkelon Marina, located between Delila and Bar Kochba beaches, offers a shipyard and repair services. Ashkeluna is a water-slide park on Ashkelon beach.[55]

Ashkelon National Park

The ancient site of Ashkelon is now a national park on the city's southern coast. The walls that encircled the city are still visible, as well as Canaanite earth ramparts. The park contains Byzantine, Crusader and Roman ruins.[61] The largest dog cemetery in the ancient world was discovered in Ashkelon.[62]

Health care

Barzilai Medical Center

Ashkelon and environs is served by the Barzilai Medical Center, established in 1961.[59] It was built in place of Hussein ibn Ali's 11th-century mosque, a center of Muslim pilgrimages, destroyed by the Israeli army in 1950.[63] Situated six miles (9.7 km) from Gaza, the hospital has been the target of numerous Qassam rocket attacks, sometimes as many as 140 over one weekend. The hospital plays a vital role in treating wounded soldiers and terror victims.[64] A new rocket and missile-proof emergency room is under construction.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1955 | 16,600 | — |

| 1961 | 24,300 | +46.4% |

| 1972 | 43,000 | +77.0% |

| 1983 | 52,900 | +23.0% |

| 1995 | 83,100 | +57.1% |

| 2008 | 110,600 | +33.1% |

| 2010 | 114,500 | +3.5% |

| 2011 | 117,400 | +2.5% |

Source:

| ||

In the early years, the city was primarily settled by Mizrahi Jews, who fled to Israel after being expelled from Muslim lands. Today, Mizrahi Jews still constitute the majority of the population. In the early 1950s, many South African Jews settled in Ashkelon, establishing the Afridar neighbourhood. They were followed by an influx of immigrants from the United Kingdom.[66] During the 1990s, the city received additional arrivals of Ethiopian Jews and Russian Jews.

Culture and sports

Ashkelon arena

The Ashkelon Sports Arena opened in 1999. The "Jewish Eye" is a Jewish world film festival

that takes place annually in Ashkelon. The festival marked its seventh year in 2010.[67]

The Breeza Music Festival has been held yearly in and around Ashkelon's amphitheatre since 1992. Most of the musical performances are free. Israel Lacrosse operates substantial youth lacrosse programs in the city and recently hosted the Turkey men's national team in Israel's first home international in 2013.[68]

Im schwarzen Walfisch zu Askalon ("In Ashkelon's Black Whale inn") is a traditional German academic commercium song and describing a drinking binge staged in the ancient city.[69]

Photos

Park Afridar, Ashqelon

Night view from Marina

Beach of Ashqelon

View on sea from the city

Street "Ha-Tayassim"

View on Ashkelon in the time of khamsin

Twin towns – sister cities

Ashkelon is twinned with:

Côte Saint-Luc, Quebec, Canada

Côte Saint-Luc, Quebec, Canada

Grodno, Belarus

Grodno, Belarus

Xinyang, China

Xinyang, China

Iquique, Chile

Iquique, Chile

Aix-en-Provence, France[70][71]

Aix-en-Provence, France[70][71]

Vani, Georgia[72]

Vani, Georgia[72]

Kutaisi, Georgia

Kutaisi, Georgia

Aviano, Italy

Aviano, Italy

Berlin-Pankow, Germany

Berlin-Pankow, Germany

Sopot, Poland

Sopot, Poland

Entebbe, Uganda

Entebbe, Uganda

Portland, Oregon, United States

Portland, Oregon, United States

Baltimore, Maryland, United States[73]

Baltimore, Maryland, United States[73]

Sacramento, California, United States

Sacramento, California, United States

Notable residents

Yael Abecassis (born 1967), actress and model

Yitzhak Cohen (born 1951), politician

Avi Dichter (born 1952), Israeli politician

Shlomo Glickstein (born 1958), professional tennis player

Boris Polak (born 1954), world champion and Olympic sport shooter

See also

- Antiochus of Ascalon

References

Citations

^ ab "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Masalha, Nur (2012). The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising History, Narrating the Subaltern, Reclaiming Memory. London: Zed Books, Limited. pp. 115–116. ISBN 1848139705.

^ Morris, Benny (2008-10-01). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. p. 331. ISBN 0300145241.

^ abcdefgh B. Morris, The transfer of Al Majdal's remaining Palestinians to Gaza, 1950, in 1948 and After; Israel and the Palestinians.

^ abcdef Golan, Arnon (2003). "Jewish Settlement of Former Arab Towns and their Incorporation into the Israeli Urban System (1948–1950)". Israel Affairs. 9: 149–164. doi:10.1080/714003467.

^ Huss (1985), p. 560.

^ "shallot". New Oxford American Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-517077-1.

^ shallot. CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

^ ab Lefkovits, Etgar (April 8, 2008). "Oldest arched gate in the world restored". Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

^ "Ashkelon, Jewish Virtual Library". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Yerushalmi Sanhedrin, 6:6.

^ "Ashkelon". Project on Ancient Cultural Engagement/Brill.

^ NEGEV, A (1976). Stillwell, Richard.; MacDonald, William L.; McAlister, Marian Holland, eds. The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press – via Perseus Digital Library.

^ Eusebius (1890). "VI". In McGiffert, Arthur Cushman. The Church History of Eusebius. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, series II. §2, notes 90-91.

^ Donner, Herbert (1992). The Mosaic Map of Madaba. Kok Pharos Publishing House. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-90-3900011-3. quoted in The Madaba Mosaic Map: Ascalon

^ Bagatti, Ancient Christian Villages of Judaea and Negev, quoted in The Madaba Mosaic Map: Ascalon

^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 452

^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013

ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 840

^ Gore, Rick (January 2001). "Ancient Ashkelon". National Geographic.

^ Alex Carmel, Peter Schäfer and Yossi Ben-Artzi (1990). The Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 634–1881. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients : Reihe B, Geisteswissenschaften; Nr. 88. Wiesbaden: Reichert. p. 24,31.

^ Moshe Gil, A History of Palestine, 634–1099 (1997) p 193–194.

^ Canaan, 1927, p. 151

^ Meron Rapoport, History Erased, Haaretz, 5 July 2007. [1]

^ abcde Orna Cohen (2007). "Transferred to Gaza of Their Own Accord" The Arabs of Majdal in Ashkelon and their Evacuation to the Gaza Strip in 1950. The Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 144

^ Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine under Muslim Rule AD 600–1600. BAR International Series 1381. p. 133.

^ Socin, 1879, p. 157

^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 131, noted 655 houses

^ Palestine Office of Statistics, Vital Statistical Tables 1922–1945, Table A8.

^ Palestinian costumes

^ "H.M. Stationery Office (1920) Syria and Palestine" — Viewer — World Digital Library". www.wdl.org.

^ Shelagh Weir, "Palestinian Costume". British Museum Publications, 1989.

ISBN 978-0-7141-1597-9. pages 27–32. Other fabrics produced include Shash (white muslin for veils), Burk/Bayt al-shem (plain cotton for underdresses), Karnaish (white cotton with stripes), "Bazayl" (flannelette), Durzi (blue cotton) and Dendeki (red cotton).

^ Morris, 2004, pp. 528 –529.

^ S. Jiryis, The Arabs in Israel (1968), p.57

^ ab Kafkafi, Eyal (1998). "Segregation or integration of the Israeli Arabs – two concepts in Mapai". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 30 (03): 347–367. doi:10.1017/S0020743800066216.

^ "Security Council". International Organization. 6 (1): 76–88. 1952. doi:10.1017/s0020818300016209.

^ "מגדל־גד בהתפתחותה,בחירות ב־26 בפברואר - דבר,". jpress.org.il (in Hebrew).

^ BENZAQUEN, JOHN. "Neighborhood Watch: Ashkelon's 'Anglo quarter'". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com.

^ "Israeli City Shocked As Rockets Hit". Associated Press. 3 March 2008.

^ Bassok, Moti (16 May 2007). "Ashkelon, Sderot residents file 1,000 damage claims over recent rocket attacks". Haaretz. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ "Iranian made rocket strikes Ashkelon – Ashkelon". Jeruselum Post. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

^ "'Improved' Kassam slams into Ashkelon school". Jta.org. 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ "Israel hit by rockets and mortars". Newsblaze.com. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ "Jerusalem Mayor: We cannot discriminate against Arabs". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com.

^ HO, SPENCER. "PM, senior ministers pan Ashkelon mayor for barring Arab workers". www.timesofisrael.com.

^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 117

^ ab Margalit, Talia. "Periphery without a center". Haaretz. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Media, JNi. "With 32,000 New Housing Units Ashkelon to Become Israel's 6th Largest City". www.jewishpress.com.

^ Israel is No. 5 on Top 10 Cleantech List in Israel 21c A Focus Beyond Archived 16 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-12-21

^ Desalination Plant Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) Plant Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

^ "Ashkelon desalination plant – A successful challenge". Desalination. 203: 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2006.03.525.

^ "Ashkelon Seawater Reverse Osmosis". Water-technology.net. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ "The Central Bottling Company Group – Company Profile". Dun & Bradstreet Israel – Dun's 100 Israel's Largest Enterprises 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

^ summer school program in Ashkelon[dead link]

^ abcde "Places to see in Ashkelon". Israel-a-la-carte.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Cecil Roth (1972). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopaedia Judaica. p. 714. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

^ Israel and the Palestinian territories: The rough guide, Daniel Jacobs, Shirley Eber, Francesca Silvani. Google Books. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ ab Meron Rapoport, 'History Erased,' at Haaretz 5 July 2007.

^ ab "Shiites in Ashkelon?". Latimesblogs.latimes.com. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Claudine M. Dauphin (1996). "Brothels, Baths and Babes: Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land". Classics Ireland. 3: 47–72. doi:10.2307/25528291.

^ "Ashkelon National Park". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Stager, Lawrence. "Why were dogs buried at Ashkelon". Bib-arch.org. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Rapoport, Meron (2014-10-05). "History Erased". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2014-10-04.

^ "Steady rain of missiles strains Israeli hospital". Njjewishnews.com. 8 April 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

^ "Statistical Abstract of Israel 2012 - No. 63 Subject 2 - Table No. 15". .cbs.gov.il. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

^ "Nefesh b'Nefesh community guide". Nbn.org.il. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ "Jewish Eye world film festival". Jewisheye.org.il. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ cite web|url=http://laxallstars.com/an-israel-lacrosse-experience-rob-berkenblit/ |title=An Israel Lacrosse experience |publisher=laxallstars.com |date=19 August 2013 |accessdate=2013-13-09| archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://laxallstars.com/an-israel-lacrosse-experience-rob-berkenblit/%7C archivedate= 19 August 2013

^ Introduction to German Poetry: A Dual-Language Book, Gustave Mathieu, Guy Stern Courier Dover Publications, 31.05.2012, including as well a translation

^ "Association of twinnings and international relations of Aix-en-Provence". Aix-jumelages.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

^ Mairie of Aix-en-Provence – Twinnings and partnerships Archived 13 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

^ Vani.org.ge — Twinned Cities

^ "Baltimore City Mayor's Office of International and Immigrant Affairs – Sister Cities Program". Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Canaan, T. (1927). Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine. London: Luzac & Co.

Garfinkel, Y.; Dag, D.; Hesse, B.; Wapnish, P.; Rookis, D.; Hartman, G.; Bar-Yosef, D.E.; Lernau, O. (2005). "Neolithic Ashkelon: Meat Processing and Early Pastoralism on the Mediterranean Coast". Eurasian Prehistory. 3: 43–72.

Garfinkel, Y.; Dag, D. (2008). Neolithic Ashkelon. Qedem 47. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University. OCLC 494272503.

Golan, Arnon (2003). "Jewish Settlement of Former Arab Towns and their Incorporation into the Israeli Urban System (1948–1950)". Israel Affairs. 9: 149–164. doi:10.1080/714003467.

Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

Huss, Werner (1985), Geschichte der Karthager, Munich: C.H. Beck. (in German)

Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

Kafkafi, Eyal (1998). "Segregation or Integration of the Israeli Arabs: Two Concepts in Mapai". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 30 (3): 347–367. doi:10.1017/S0020743800066216.

Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

Morris, . (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 210-213. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des D eutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

Townsend, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Penguin Books ltd. ISBN 978-0-7139-9220-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashkelon. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ashkelon. |

- Ashkelon City Council

"Ashkelon, ancient city of the sea", National Geographic, January 2001

Ancient Ashkelon—University of Chicago

Pictures of Ashkelon—Holy Land Pictures