Albert Sidney Johnston

Multi tool use

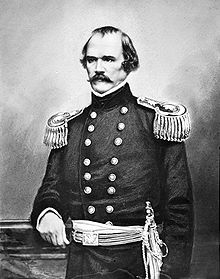

General Albert Sidney Johnston | |

|---|---|

Albert Sidney Johnston, circa 1860-1862 | |

| Born | (1803-02-02)February 2, 1803 Washington, Kentucky |

| Died | April 6, 1862(1862-04-06) (aged 59) Hardin County, Tennessee |

| Buried | Texas State Cemetery, Austin, Texas |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1826–1834; 1846–1861 (USA) 1836–1840 (Republic of Texas) 1861–1862 (CSA) |

| Rank | Brevet Brigadier General (USA) Senior Brigadier General (Texas) General (CSA) |

| Unit | 2nd U.S. Infantry 6th U.S. Infantry Los Angeles Mounted Rifles (CSA) |

| Commands held | 1st Texas Rifles (USV) 2nd U.S. Cavalry Department of the Pacific (USA) Army of Central Kentucky (CSA) Army of Mississippi (CSA) Department No. 2 (CSA) |

| Battles/wars | Black Hawk War (1832) Texas Revolution (1835-1836) Mexican–American War (1846-1848)

Utah War (1857-1858)

|

| Signature | |

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, fighting actions in the Black Hawk War, the Texas War of Independence, the Mexican–American War, the Utah War, and the American Civil War.

Considered by Confederate States President Jefferson Davis to be the finest general officer in the Confederacy before the later emergence of Robert E. Lee, he was killed early in the Civil War at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862. Johnston was the highest-ranking officer, Union or Confederate, killed during the entire war. Davis believed the loss of General Johnston "was the turning point of our fate."

Johnston was unrelated to Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Marriage and family

3 Texian Army

4 United States Army

5 Utah War

6 Civil War

6.1 Confederate command in Western Theater

6.2 Battle of Mill Springs

6.3 Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Nashville

6.4 Concentration at Corinth

6.5 Battle of Shiloh and death

7 Legacy and honors

8 See also

9 Notes

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Early life and education

Johnston was born in Washington, Kentucky, the youngest son of Dr. John and Abigail (Harris) Johnston. His father was a native of Salisbury, Connecticut. Although Albert Johnston was born in Kentucky, he lived much of his life in Texas, which he considered his home. He was first educated at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, where he met fellow student Jefferson Davis. Both were appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, Davis two years behind Johnston.[1] In 1826, Johnston graduated eighth of 41 cadets in his class from West Point with a commission as a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry.[2]

Johnston was assigned to posts in New York and Missouri and served in the brief Black Hawk War in 1832 as chief of staff to Bvt. Brig. Gen. Henry Atkinson.

Marriage and family

In 1829 he married Henrietta Preston, sister of Kentucky politician and future Civil War general William Preston. They had one son, William Preston Johnston, who became a colonel in the Confederate States Army.[3] The senior Johnston resigned his commission in 1834 in order to care for his dying wife in Kentucky, who succumbed two years later to tuberculosis.[1]

After serving as Secretary of War for the Republic of Texas from 1838 to 1840, Johnston resigned and returned to Kentucky. In 1843, he married Eliza Griffin, his late wife's first cousin. The couple moved to Texas, where they settled on a large plantation in Brazoria County. Johnston named the property "China Grove". Here they raised Johnston's two children from his first marriage and the first three children born to Eliza and him. (A sixth child was born later when they lived in Los Angeles).

Texian Army

In 1836 Johnston moved to Texas. He enlisted as a private in the Texian Army during the Texas War of Independence against the Republic of Mexico. He was named Adjutant General as a colonel in the Republic of Texas Army on August 5, 1836. On January 31, 1837, he became senior brigadier general in command of the Texas Army.

On February 5, 1837, he fought in a duel with Texas Brig. Gen. Felix Huston, as they challenged each other for the command of the Texas Army; Johnston refused to fire on Huston and lost the position after he was wounded in the pelvis.

On December 22, 1838, Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas, appointed Johnston as Secretary of War. He provided for the defense of the Texas border against Mexican invasion, and in 1839 conducted a campaign against Indians in northern Texas. In February 1840, he resigned and returned to Kentucky.

United States Army

Johnston as commander of the Department of Utah. Portrait taken by Samuel C. Mills at Camp Floyd, Utah Territory, winter of 1858–59.

Johnston returned to Texas during the Mexican–American War (1846-1848), under General Zachary Taylor as a colonel of the 1st Texas Rifle Volunteers. The enlistments of his volunteers ran out just before the Battle of Monterrey. Johnston convinced a few volunteers to stay and fight as he served as the inspector general of volunteers and fought at the battles of Monterrey and Buena Vista.

He remained on his plantation after the war until he was appointed by later 12th President Zachary Taylor to the U.S. Army as a major and was made a paymaster in December 1849. He served in that role for more than five years, making six tours, and traveling more than 4,000 miles (6,400 km) annually on the Indian frontier of Texas. He served on the Texas frontier at Fort Mason and elsewhere in the West.

In 1855, 14th President Franklin Pierce appointed him colonel of the new 2nd U.S. Cavalry (the unit that preceded the modern 5th U.S.), a new regiment, which he organized. On August 19, 1856, Gen. Persifor Smith, at the request of Kansas Territorial Governor Wilson Shannon, sent Col. Johnston with 1300 men composed of the 2d Cavalry Dragoons from Fort Riley, a battalion of the 6th Infantry and Capt. Howe's artillery company from Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis to protect the territorial capital at Lecompton from an imminent attack by James Henry Lane and his abolitionist "Army of the North."

Utah War

As a key figure in the Utah War, Johnston led U.S. troops who established a non-Mormon government in the Mormon territory. He received a brevet promotion to brigadier general in 1857 for his service in Utah. He spent 1860 in Kentucky until December 21, when he sailed for California to take command of the Department of the Pacific.

Civil War

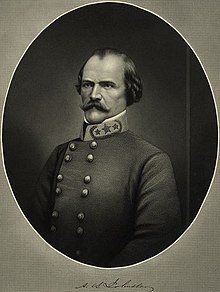

Albert S. Johnston in Confederate Army uniform wearing Three Gold Stars and Wreath on a General's Collar

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Johnston was the commander of the U.S. Army Department of the Pacific in California. Like many regular army officers from the South, he was opposed to secession. But he resigned his commission soon after he heard of the secession of his adopted state of Texas. It was accepted by the War Department on May 6, 1861, effective May 3.[4] On April 28 he moved to Los Angeles, the home of his wife's brother John Griffin. Considering staying in California with his wife and five children, Johnston remained there until May.

Soon, under suspicion by local Union officials, he evaded arrest and joined the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles as a private, leaving Warner's Ranch May 27.[5] He participated in their trek across the southwestern deserts to Texas, crossing the Colorado River into the Confederate Territory of Arizona on July 4, 1861.

Early in the Civil War, Confederate President Jefferson Davis decided that the Confederacy would attempt to hold as much of its territory as possible, and therefore distributed military forces around its borders and coasts.[6] In the summer of 1861, Davis appointed several generals to defend Confederate lines from the Mississippi River east to the Allegheny Mountains.[7]

The most sensitive, and in many ways the most crucial areas, along the Mississippi River and in western Tennessee along the Tennessee and the Cumberland rivers[8] were placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk and Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow. The latter had initially been in command in Tennessee as that State's top general.[9] Their impolitic occupation of Columbus, Kentucky, on September 3, 1861, two days before Johnston arrived in the Confederacy's capital of Richmond, Virginia, after his cross-country journey, drove Kentucky from its stated neutrality.[10][11] The majority of Kentuckians allied with the Union camp.[12] Polk and Pillow's action gave Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant an excuse to take control of the strategically located town of Paducah, Kentucky, without raising the ire of most Kentuckians and the pro-Union majority in the State legislature.[13][14]

Confederate command in Western Theater

On September 10, 1861, Johnston was assigned to command the huge area of the Confederacy west of the Allegheny Mountains, except for coastal areas. He became commander of the Confederacy's western armies in the area often called the Western Department or Western Military Department.[15][16] Johnston's appointment as a full general by his friend and admirer Jefferson Davis already had been confirmed by the Confederate Senate on August 31, 1861. The appointment had been backdated to rank from May 30, 1861, making him the second highest ranking general in the Confederate States Army. Only Adjutant General and Inspector General Samuel Cooper ranked ahead of him.[17] After his appointment, Johnston immediately headed for his new territory.[18] He was permitted to call on governors of Arkansas, Tennessee and Mississippi for new troops, although this authority was largely stifled by politics, especially with respect to Mississippi.[15] On September 13, 1861, Johnston ordered Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer with 4,000 men to occupy Cumberland Gap in Kentucky in order to block Union troops from coming into eastern Tennessee. The Kentucky legislature had voted to side with the Union after the occupation of Columbus by Polk.[18] By September 18, Johnston had Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner with another 4,000 men blocking the railroad route to Tennessee at Bowling Green, Kentucky.[18][19]

Johnston had fewer than 40,000 men spread throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas and Missouri.[20] Of these, 10,000 were in Missouri under Missouri State Guard Maj. Gen. Sterling Price.[20] Johnston did not quickly gain many recruits when he first requested them from the governors, but his more serious problem was lacking sufficient arms and ammunition for the troops he already had.[20] As the Confederate government concentrated efforts on the units in the East, they gave Johnston small numbers of reinforcements and minimal amounts of arms and material.[21] Johnston maintained his defense by conducting raids and other measures to make it appear he had larger forces than he did, a strategy that worked for several months.[21] Johnston's tactics had so annoyed and confused Union Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in Kentucky that he became paranoid and mentally unstable. Sherman overestimated Johnston's forces, and had to be relieved by Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell on November 9, 1861.[22][23][24]

Battle of Mill Springs

East Tennessee (a heavily pro-Union region of the South during the Civil War) was held for the Confederacy by two unimpressive brigadier generals appointed by Jefferson Davis: Felix Zollicoffer, a brave but untrained and inexperienced officer, and soon-to-be Maj. Gen. George B. Crittenden, a former U.S. Army officer with apparent alcohol problems.[25] While Crittenden was away in Richmond, Zollicoffer moved his forces to the north bank of the upper Cumberland River near Mill Springs (now Nancy, Kentucky), putting the river to his back and his forces into a trap.[26][27] Zollicoffer decided it was impossible to obey orders to return to the other side of the river because of scarcity of transport and proximity of Union troops.[28] When Union Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas moved against the Confederates, Crittenden decided to attack one of the two parts of Thomas's command at Logan's Cross Roads near Mill Springs before the Union forces could unite.[28] At the Battle of Mill Springs on January 19, 1862, the ill-prepared Confederates, after a night march in the rain, attacked the Union force with some initial success.[29] As the battle progressed, Zollicoffer was killed, Crittenden was unable to lead the Confederate force (he may have been intoxicated), and the Confederates were turned back and routed by a Union bayonet charge, suffering 533 casualties from their force of 4,000.[30][31] The Confederate troops who escaped were assigned to other units as General Crittenden faced an investigation of his conduct.[32]

After the Confederate defeat at the Mill Springs, Davis sent Johnston a brigade and a few other scattered reinforcements. He also assigned him Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, who was supposed to attract recruits because of his victories early in the war, and act as a competent subordinate for Johnston.[33] The brigade was led by Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, considered incompetent. He took command at Fort Donelson as the senior general present just before Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant attacked the fort.[34] Historians believe the assignment of Beauregard to the west stimulated Union commanders to attack the forts before Beauregard could make a difference in the theater. Union officers heard that he was bringing 15 regiments with him, but this was an exaggeration of his forces.[35]

Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Nashville

Based on the assumption that Kentucky neutrality would act as a shield against a direct invasion from the north, circumstances that no longer applied in September 1861, Tennessee initially had sent men to Virginia and concentrated defenses in the Mississippi Valley.[36][37] Even before Johnston arrived in Tennessee, construction of two forts had been started to defend the Tennessee and the Cumberland rivers, which provided avenues into the State from the north.[38] Both forts were located in Tennessee in order to respect Kentucky neutrality, but these were not in ideal locations.[38][39][40][41]Fort Henry on the Tennessee River was in an unfavorable low-lying location, commanded by hills on the Kentucky side of the river.[38]Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, although in a better location, had a vulnerable land side and did not have enough heavy artillery to defend against gunboats.[38]

Maj. Gen. Polk ignored the problems of the forts when he took command. After Johnston took command, Polk at first refused to comply with Johnston's order to send an engineer, Lt. Joseph K. Dixon, to inspect the forts.[42] After Johnston asserted his authority, Polk had to allow Dixon to proceed. Dixon recommended that the forts be maintained and strengthened, although they were not in ideal locations, because much work had been done on them and the Confederates might not have time to build new ones. Johnston accepted his recommendations.[42] Johnston wanted Major Alexander P. Stewart to command the forts but President Davis appointed Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman as commander.[39][42]

To prevent Polk from dissipating his forces by allowing some men to join a partisan group, Johnston ordered him to send Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow and 5,000 men to Fort Donelson.[43] Pillow took up a position at nearby Clarksville, Tennessee and did not move into the fort until February 7, 1862.[44][45] Alerted by a Union reconnaissance on January 14, 1862, Johnston ordered Tilghman to fortify the high ground opposite Fort Henry, which Polk had failed to do despite Johnston's orders.[46] Tilghman failed to act decisively on these orders, which in any event were too late to be adequately carried out.[46][47][48]

Gen. Beauregard arrived at Johnston's headquarters at Bowling Green on February 4, 1862, and was given overall command of Polk's force at the western end of Johnston's line at Columbus, Kentucky.[49][50] On February 6, 1862, Union Navy gunboats quickly reduced the defenses of ill-sited Fort Henry, inflicting 21 casualties on the small remaining Confederate force.[51][52] Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman surrendered the 94 remaining officers and men of his approximately 3,000-man force which had not been sent to Fort Donelson before U.S. Grant's force could even take up their positions.[51][53][54] Johnston knew he could be trapped at Bowling Green if Fort Donelson fell, so he moved his force to Nashville, the capital of Tennessee and an increasingly important Confederate industrial center, beginning on February 11, 1862.[55][56]

Johnston also reinforced Fort Donelson with 12,000 more men, including those under Floyd and Pillow, a curious decision in view of his thought that the Union gunboats alone might be able to take the fort.[55] He did order the commanders of the fort to evacuate the troops if the fort could not be held.[57] The senior generals sent to the fort to command the enlarged garrison, Gideon J. Pillow and John B. Floyd, squandered their chance to avoid having to surrender most of the garrison[58] and on February 16, 1862, Brig. Gen. Simon Buckner, having been abandoned by Floyd[59] and Pillow, surrendered Fort Donelson.[60] Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest escaped with his cavalry force of about 700 men before the surrender.[61][62][63] The Confederates suffered about 1,500 casualties with an estimated 12,000 to 14,000 taken prisoner.[64][65] Union casualties were 500 killed, 2,108 wounded, 224 missing.[65]

Johnston, who had little choice in allowing Floyd and Pillow to take charge at Fort Donelson on the basis of seniority after he ordered them to add their forces to the garrison, took the blame and suffered calls for his removal because a full explanation to the press and public would have exposed the weakness of the Confederate position.[66] His passive defensive performance while positioning himself in a forward position at Bowling Green, spreading his forces too thinly, not concentrating his forces in the face of Union advances, and appointing or relying upon inadequate or incompetent subordinates subjected him to criticism at the time and by later historians.[67][68][69] The fall of the forts exposed Nashville to imminent attack, and it fell without resistance to Union forces under Brig. Gen. Buell on February 25, 1862, two days after Johnston had to pull his forces out in order to avoid having them captured as well.[70][71][72]

Concentration at Corinth

Johnston had various remaining military units scattered throughout his territory and retreating to the south to avoid being cut off.[73] Johnston himself retreated with the force under his personal command, the Army of Central Kentucky, from the vicinity of Nashville.[70] With Beauregard's help,[74] Johnston decided to concentrate forces with those formerly under Polk and now already under Beauregard's command at the strategically located railroad crossroads of Corinth, Mississippi, which he reached by a circuitous route.[75] Johnston kept the Union forces, now under the overall command of the ponderous Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, confused and hesitant to move, allowing Johnston to reach his objective undetected.[76] This delay allowed Jefferson Davis finally to send reinforcements from the garrisons of coastal cities and another highly rated but prickly general, Braxton Bragg, to help organize the western forces.[77] Bragg at least calmed the nerves of Beauregard and Polk, who had become agitated by their apparent dire situation in the face of numerically superior forces, before Johnston's arrival on March 24, 1862.[78][79]

Johnston's army of 17,000 men gave the Confederates a combined force of about 40,000 to 44,669 men at Corinth.[78][74][80] On March 29, 1862, Johnston officially took command of this combined force, which continued to use the Army of the Mississippi name under which it had been organized by Beauregard on March 5.[81][82]

Johnston now planned to defeat the Union forces piecemeal before the various Union units in Kentucky and Tennessee under Grant with 40,000 men at nearby Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, and the now Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell on his way from Nashville with 35,000 men, could unite against him.[78] Johnston started his army in motion on April 3, 1862, intent on surprising Grant's force as soon as the next day, but they moved slowly due to their inexperience, bad roads, and lack of adequate staff planning.[83][84] Due to the delays, as well as several contacts with the enemy, Johnston's second in command, P. G. T. Beauregard, felt the element of surprise had been lost and recommended calling off the attack. Johnston decided to proceed as planned, stating "I would fight them if they were a million."[85] His army was finally in position within a mile or two of Grant's force, and undetected, by the evening of April 5, 1862.[86][87][88][89][90]

Battle of Shiloh and death

Monument to Johnston at Shiloh National Military Park

Johnston launched a massive surprise attack with his concentrated forces against Grant at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862. As the Confederate forces overran the Union camps, Johnston seemed to be everywhere, personally leading and rallying troops up and down the line on his horse. At about 2:30 pm, while leading one of those charges against a Union camp near the "Peach Orchard," he was wounded, taking a bullet behind his right knee. He apparently did not think the wound was serious at the time, or even possibly did not feel it. It is possible that Johnston's duel in 1837 had caused nerve damage or numbness to his right leg and that he did not feel the wound to his leg as a result. The bullet had in fact clipped a part of his popliteal artery and his boot was filling up with blood. There were no medical personnel on scene at the time, since Johnston had sent his personal surgeon to care for the wounded Confederate troops and Yankee prisoners earlier in the battle.[91]

Within a few minutes, Johnston was observed by his staff to be nearly fainting. Among his staff was Isham G. Harris, the Governor of Tennessee, who had ceased to make any real effort to function as governor after learning that Abraham Lincoln had appointed Andrew Johnson as military governor of Tennessee. Seeing Johnston slumping in his saddle and his face turning deathly pale, Harris asked: "General, are you wounded?" Johnston glanced down at his leg wound, then faced Harris and replied in a weak voice his last words: "Yes... and I fear seriously." Harris and other staff officers removed Johnston from his horse and carried him to a small ravine near the "Hornets Nest" and desperately tried to aid the general who had lost consciousness by this point. Harris then sent an aide to fetch Johnston's surgeon but did not apply a tourniquet to Johnson's wounded leg. Before a doctor could be found, Johnston died from blood loss a few minutes later. It is believed that Johnston may have lived for as long as one hour after receiving his fatal wound. Ironically, it was later discovered that Johnston had a tourniquet in his pocket when he died.[91]

Harris and the other officers wrapped General Johnston's body in a blanket so as not to damage the troops' morale with the sight of the dead general. Johnston and his wounded horse, Fire Eater, were taken to his field headquarters on the Corinth road, where his body remained in his tent until the Confederate Army withdrew to Corinth the next day, April 7, 1862, after failing to gain a decisive victory over the Union armies. From there, his body was taken to the home of Colonel William Inge, which had been his headquarters in Corinth. It was covered in the Confederate flag and lay in state for several hours.[92]

It is probable that a Confederate soldier fired the fatal round. No Union soldiers had ever been observed to have gotten behind Johnston during the fatal charge, but it is known that many Confederates were firing at the Union lines while Johnston charged well in advance of his soldiers.[93] Furthermore, the surgeon who later dug the bullet out of Johnston's leg identified the round as one fired from a Pattern 1853 Enfield. No Union troops in the area in which Johnston was hit had been issued Enfield rifles, but the Enfield rifle was standard issue for the Confederate forces Johnston was leading.[94]

Johnston was the highest-ranking fatality of the war on either side,[2][95] and his death was a strong blow to the morale of the Confederacy. At the time, Davis considered him the best general in the country.[96]

Legacy and honors

Johnston's tomb and statue by Elisabet Ney in the Texas State Cemetery in Austin, Texas

Johnston was survived by his wife Eliza and six children. His wife and five younger children, including one born after he went to war, chose to live out their days at home in Los Angeles with Eliza's brother, Dr. John Strother Griffin.[97] Johnston's eldest son, Albert Sidney Jr. (born in Texas), had already followed him into the Confederate States Army. In 1863, after taking home leave in Los Angeles, Albert Jr. was on his way out of San Pedro harbor on a ferry. While a steamer was taking on passengers from the ferry, a wave swamped the smaller boat, causing its boilers to explode. Albert Jr. was killed in the accident.[98]

Killed in action, General Johnston received the highest praise ever given by the Confederate government: accounts were published, on December 20, 1862, and thereafter, in the Los Angeles Star of his family's hometown.[99] Johnston Street, Hancock Street, and Griffin Avenue, each in northeast Los Angeles, are named after the general and his family, who lived in the neighborhood.

Johnston was initially buried in New Orleans. In 1866, a joint resolution of the Texas Legislature was passed to have his body moved and reinterred at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. The re-interment occurred in 1867.[100] Forty years later, the state appointed Elisabet Ney to design a monument and sculpture of him to be erected at the grave site, installed in 1905.[101]

The Texas Historical Commission has erected a historical marker near the entrance of what was once Johnston's plantation. An adjacent marker was erected by the San Jacinto Chapter of the Daughters of The Republic of Texas and the Lee, Roberts, and Davis Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederate States of America.

In 1916, the University of Texas at Austin recognized several confederate veterans (including Johnston) with statues on its South Mall. On August 21, 2017, as part of the wave of confederate monument removals in America, Johnston's statue was taken down. Plans were announced to add it to the Briscoe Center for American History on the east side of the university campus.[102]

In the fall of 2018, A.S. Johnston Elementary School in Dallas, Texas, was renamed Cedar Crest Elementary. Three additional elementary schools named for confederate veterans were renamed at the same time.[103]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- List of monuments and memorials of the Confederate States of America

Notes

^ ab Woodworth, p. 46.

^ ab Eicher, p. 322.

^ W.P. Johnston biography. Archived December 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

^ Johnston, p. 273.

^ Johnston, pp. 268, 275–91.

^ Woodworth, pp. 18–19.

^ Woodworth, pp. 17–33.

^ Woodworth, pp. 20–22

^ Woodworth, pp. 30–32.

^ Woodworth, pp. 35, 45.

^ Long, p. 114.

^ Woodworth, pp. 39, 50.

^ Woodworth, p. 39.

^ Long, p. 115.

^ ab Woodworth, p. 51.

^ Long, p. 116.

^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands. p. 807. From General Command Line List. Weigley, p. 110. McPherson, p. 394.

^ abc Woodworth, p. 52.

^ Long, p. 119.

^ abc Woodworth, p. 53.

^ ab Woodworth, p. 55.

^ Woodworth, pp. 55–56

^ Long, p. 138.

^ McPherson, p. 394 says Johnston had 70,000 troops to defend his territory between the Appalachians and the Ozarks by the end of 1861.

^ Woodworth, p. 61

^ Woodworth, p. 65.

^ Long, pp. 161–162.

^ ab Woodworth, p. 66.

^ Woodworth, pp. 66–67.

^ Woodworth, p. 67.

^ Long, p. 162.

^ Woodworth, p. 69.

^ Woodworth, pp. 71–72.

^ Woodworth, pp. 80, 84.

^ Woodworth, pp. 72, 78.

^ Woodworth, p. 54.

^ Eicher, The Longest Night. pp. 111–113.

^ abcd Woodworth, p. 56.

^ ab Long, p. 142

^ Weigley, p. 108

^ McPherson, p. 393.

^ abc Woodworth, p. 57.

^ Woodworth, p. 58.

^ Long, pp. 167–168.

^ Eicher, The Longest Night, p. 171 says the garrison at Fort Donelson numbered 1,956 men before the Fort Henry garrison and the men under Floyd and Pillow joined them in early February 1862.

^ ab Woodworth, p. 71.

^ McPherson, p. 396.

^ A Confederate battery and the beginning of some fortifications were sited across the river at Fort Heiman but these were of little value when the Union flotilla appeared.

^ Woodworth, p. 78.

^ After some preliminary work with Johnston, Beauregard assumed command of this force, which he named the Army of the Mississippi, on March 5, 1862, while at Jackson, Tennessee. Like the other Confederate commander, he had to withdraw to the south after the fall of the forts or be surrounded by the advancing Union forces. Long, p. 178.

^ ab Woodworth, pp. 78–79.

^ Long, p. 167.

^ Long, pp. 166–167

^ Weigley, p. 109.

^ ab Woodworth, p. 79.

^ Loing, pp. 169–170.

^ Woodworth, p. 80.

^ McPherson, pp. 400–401.

^ Floyd was able to ferry his four Virginia regiments out of the fort with him but left his Mississippi regiment behind to surrender with the rest of the garrison. Pillow escaped only with his chief of staff. Woodworth, p. 83. Long, p. 171.

^ Woodworth, pp. 82–84.

^ Woodworth, p. 84.

^ McPherson, pp. 401–402.

^ This included about 200 men not in Forrest's immediate command. Weigley, p. 111

^ Long, p. 172.

^ ab Weigley, p. 111.

^ Woodworth, pp. 84–85.

^ Weigley, p. 112.

^ McPherson, pp. 405–406.

^ Davis defended Johnston, saying: "If Sidney Johnston is not a general, we had better give up the war, for we have no general." McPherson, p. 495.

^ ab Woodworth, p. 86.

^ Long, p. 175.

^ McPherson, p. 402.

^ Woodworth, pp. 85–86.

^ ab McPherson, p. 406.

^ Woodworth, pp. 86–88.

^ Woodworth, p. 88.

^ Woodworth, pp. 90, 94.

^ abc Woodworth, p. 95.

^ Long, p. 188.

^ Eicher, The Longest Night, p. 223.

^ Long, 190.

^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands p. 887 and Eicher, The Longest Night p. 219 are nearly alone in referring to this army as the Army of Mississippi. Muir, p. 85, in discussing the first "Army of Mississippi" includes this army as one of three in the article with that title but states: "Historians have pointed out that the Army of Mississippi is frequently mentioned in the Official Records as the Army of the Mississippi." Contemporaries, including Johnston and Beauregard, and modern historians call this Confederate army the Army of the Mississippi. 'The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies.', Volume X, Part 1, index, pp. 96–99; 385 (Beauregard's report on the Battle of Shiloh, April 11, 1862, from Headquarters, Army of the Mississippi) and Part 2, p. 297 (Beauregard's announcement on taking command of Army of the Mississippi); p. 370 (Johnston General Orders of March 29, 1862, assuming command and announcing the army would retain the name Army of the Mississippi); pp. 405–409. Beauregard, p. 579. Boritt, p. 53. Connelly, Army of the Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, 1861–1862. p. 151. ("The Army retained Beauregard's chosen name...") Connelly, Civil War Tennessee: Battles And Leaders. p. 35. Cunningham, pp. 98, 122, 397. Engle, p. 123. Hattaway, p. 163. Hess, pp. 47, 49, 112 ("...Braxton Bragg's renamed Army of Tennessee (formerly the Army of the Mississippi)..."). Isbell, p. 102. McDonough, pp. 60, 66, 78. Kennedy, p. 48. Noe, p. 19. Williams, p. 122.

^ Woodworth, pp. 96–97.

^ Long, p. 192

^ McWhiney; Jamieson, p. 162.

^ Woodworth, p. 97.

^ Long, pp. 193–194.

^ Weigley, p. 113.

^ McPherson, pp. 406–407.

^ Johnston did not achieve total surprise as some Union pickets were alerted to the Confederate presence and provided warning to some Union units before the attack began.

^ ab "Battlefield Tours: Full Tour Shiloh". Civil War Landscapes Association. Retrieved 3 February 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Sword, pp. 270–73, 443–46; Cunningham, pp. 273–76; Smith, pp. 26–34. Sword offers evidence that Johnston lived as long as an hour after receiving his fatal wound.

^ Sword, p. 444.

^ "Who killed Albert Sidney Johnston". Tim Kent's Civil War tales. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

^ Johnston is the only four-star (full) American general ever killed in battle. Muir, p. 84.

^ Dupuy, p. 378.

^ "JOHNSTON, ELIZA GRIFFIN". Texas State Historical Association.

^ "Los Angeles Star, vol. 13, no. 2, May 16, 1863".

^ "Los Angeles Star, vol. 12, no. 33, December 20, 1862".

^ Cartwright, Gary (May 2008). "Remains of the Day". Texas Monthly. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

^ "Albert Sidney Johnston". Texas State Cemetery. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

^ Confederate Statues on Campus

^ Smith, Corbett (13 June 2018). "See ya, Stonewall: Dallas ISD begins to remove Confederate leaders' names from 4 schools". DallasNews.com. The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

References

- Beauregard, G. T. The Campaign of Shiloh. p. 579. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. I, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence C. Buel. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888.

OCLC 2048818.

G. S. Boritt (1999). Jefferson Davis' Generals. Oxford University Press on Demand. ISBN 978-0-19-512062-2.

Thomas Lawrence Connelly (2001). Army of the Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, 1861–1862. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2737-7.

Thomas Lawrence Connelly (1979). Civil War Tennessee: battles and leaders. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-284-6.

O. Edward Cunningham (2007). Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862. ISBN 978-1-932714-27-2.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

David J. Eicher (2001). The longest night: a military history of the Civil War. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

Civil War high commands. Stanford University Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

Stephen Douglas Engle; Bison Book (2005). Struggle for the Heartland: The Campaigns From Fort Henry To Corinth. Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-6753-4.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

ISBN 0-252-00918-5.

Earl J. Hess (2012). The Civil War in the West: Victory and Defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3542-5.

Shiloh and Corinth: Sentinels of Stone. University Press of Mississippi. 2007. ISBN 978-1-934110-08-9.

William Preston Johnston (1878). The life of Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston: embracing his services in the armies of the United States, the republic of Texas, and the Confederate States. D. Appleton.

Frances H. Kennedy; Conservation Fund (Arlington, Va) (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971.

OCLC 68283123.

James Lee McDonough (1977). Shiloh, in Hell Before Night. ISBN 978-0-87049-199-3.

McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

David Stephen Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler; David J. Coles (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5.

Noe, Kenneth (2001). Perryville. ISBN 978-0-8131-2209-0.

Smith, Derek (2005). The Gallant Dead: Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0132-7.

Sword, Wiley (1992). The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. ISBN 978-0-7006-0650-4.

Russell F. Weigley (2000). A great Civil War: a military and political history, 1861–1865. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33738-2.

T. Harry Williams (1995). P. G. T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1974-7.

Woodworth, Steven E. (1990). Jefferson Davis and His Generals: the Failure of Confederate Command in the West. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0461-8.

McWhiney, Grady; Jamieson, Perry D. (1984). Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0229-0. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

Further reading

Larry J. Daniel (1997). Shiloh: the battle that changed the Civil War. ISBN 0-684-80375-5.

Kendall D. Gott (2003). Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. ISBN 978-0-8117-0049-8.

Albert A. Nofi (2001). The Alamo: And the Texas War for Independence September 30, 1835 to April 21, 1836 : Heroes, Myths and History. ISBN 978-0-306-81040-4.

Charles Pierce Roland (1964). Albert Sidney Johnston: Soldier of Three Republics. ISBN 978-0-8131-9000-6.

Charles Pierce Roland (2000). Jefferson Davis's Greatest General: Albert Sidney Johnston. McWhiney Foundation Press. ISBN 1-893114-20-1.

External links

Albert Sidney Johnston at Handbook of Texas Online

Albert Sidney Johnston at Find a Grave

![]() Media related to Albert Sidney Johnston at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Albert Sidney Johnston at Wikimedia Commons

zodkh E9Pgj t yWFUpuZcQ 3YuiwTY,o75NY6c8H,BCSxVxWG,PbInQykiId,1YEq8OJ,zivtBnFh7cXInNE 0TCvABwLmW7