New Brunswick, New Jersey

New Brunswick, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of New Brunswick | |

One of multiple newer skyscrapers in Downtown New Brunswick, an educational and cultural district undergoing gentrification | |

| Nickname(s): Hub City, Healthcare City | |

Location of New Brunswick in Middlesex County. Inset: Location of Middlesex County highlighted in the State of New Jersey. | |

Census Bureau map of New Brunswick, New Jersey Interactive map of New Brunswick, New Jersey | |

New Brunswick Location in Middlesex County Show map of Middlesex County, New Jersey  New Brunswick Location in New Jersey Show map of New Jersey  New Brunswick Location in the United States Show map of the US  New Brunswick Location in North America Show map of North America  New Brunswick Location on Earth Show map of Earth | |

| Coordinates: 40°29′12″N 74°26′40″W / 40.486678°N 74.444414°W / 40.486678; -74.444414Coordinates: 40°29′12″N 74°26′40″W / 40.486678°N 74.444414°W / 40.486678; -74.444414[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Middlesex |

| Established | December 30, 1730 |

| Incorporated | September 1, 1784 |

| Named for | Braunschweig, Germany or King George II of Great Britain |

| Government [7] | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | James M. Cahill (D, term ends December 31, 2018)[3][4] |

| • Administrator | Thomas A. Loughlin, III[5] |

| • Municipal clerk | Daniel A. Torrisi[6] |

| Area [1] | |

| • Total | 5.789 sq mi (14.995 km2) |

| • Land | 5.227 sq mi (13.539 km2) |

| • Water | 0.562 sq mi (1.456 km2) 9.71% |

| Area rank | 264th of 566 in state 14th of 25 in county[1] |

| Elevation [8] | 62 ft (19 m) |

| Population (2010 Census)[9][10][11] | |

| • Total | 55,181 |

| • Estimate (2016)[12] | 56,910 |

| • Rank | 27th of 566 in state 5th of 25 in county[13] |

| • Density | 10,556.4/sq mi (4,075.8/km2) |

| • Density rank | 34th of 566 in state 2nd of 25 in county[13] |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Codes | 08901–08906, 08933, 08989[14][15] |

| Area code(s) | 732/848 and 908[16] |

| FIPS code | 3402351210[1][17][18] |

GNIS feature ID | 0885318[1][19] |

| Website | www.cityofnewbrunswick.org |

| New Brunswick is the county seat for Middlesex County. | |

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

— Alfred E. Smith to Lew Dockstader in December 1923 on Dockstader's fall at what is now the State Theater.[20]

New Brunswick is a city in Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States, in the New York City metropolitan area. The city is the county seat of Middlesex County,[21] and the home of Rutgers University. New Brunswick is on the Northeast Corridor rail line, 27 miles (43 km) southwest of Manhattan, on the southern bank of the Raritan River. As of 2016, New Brunswick had a Census-estimated population of 56,910,[12] representing a 3.1% increase from the 55,181 people enumerated at the 2010 United States Census,[9][10][11] which in turn had reflected an increase of 6,608 (+13.6%) from the 48,573 counted in the 2000 Census.[22] Due to the concentration of medical facilities in the area, including Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital and Saint Peter's University Hospital, as well as Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey's Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick is known as both the Hub City and the Healthcare City.[23][24] The corporate headquarters and production facilities of several global pharmaceutical companies are situated in the city, including Johnson & Johnson and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

New Brunswick is noted for its ethnic diversity. At one time, one quarter of the Hungarian population of New Jersey resided in the city and in the 1930s one out of three city residents was Hungarian.[25] The Hungarian community continues to exist, alongside growing Asian and Hispanic communities that have developed around French Street near Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Origins of the name

1.2 During the Colonial and Early American periods

1.3 African American community

1.3.1 Slavery in New Brunswick

1.3.2 African American spaces and institutions in the early 19th century

1.3.3 Jail and curfew in the 19th century

1.4 Hungarian community

1.5 Latino community

1.6 Demolition, revitalization and redevelopment

2 Geography

2.1 Climate

3 Demographics

3.1 Census 2010

3.2 Census 2000

4 Economy

4.1 Health care

4.2 Urban Enterprise Zone

5 Arts and culture

5.1 Theatre

5.2 Museums

5.3 Fine arts

5.4 Grease trucks

5.5 Music

6 Government

6.1 Local government

6.2 Police department

6.3 Federal, state and county representation

6.4 Politics

7 Education

7.1 Public schools

7.2 Higher education

8 Transportation

8.1 Roads and highways

8.2 Public transportation

9 Popular culture

10 Points of interest

11 Places of worship

12 Notable people

13 Sister cities

14 See also

15 References

16 External links

History

Origins of the name

The area around present-day New Brunswick was first inhabited by the Lenape Native Americans. The first European settlement at the site of New Brunswick was made in 1681. The settlement here was called Prigmore's Swamp (1681–1697), then known as Inian's Ferry (1691–1714).[26] In 1714, the settlement was given the name New Brunswick, after the city of Braunschweig (called Brunswick in the Low German language), in state of Lower Saxony, in Germany. Braunschweig was an influential and powerful city in the Hanseatic League and was an administrative seat for the Duchy of Hanover. Shortly after the first settlement of New Brunswick in colonial New Jersey, George, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Elector of Hanover, became King George I of Great Britain. Alternatively, the city gets its name from King George II of Great Britain, the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg.[27][28]

During the Colonial and Early American periods

Centrally located between New York City and Philadelphia along an early thoroughfare known as the King's Highway and situated along the Raritan River, New Brunswick became an important hub for Colonial travelers and traders. New Brunswick was incorporated as a town in 1736 and chartered as a city in 1784.[29] It was incorporated into a town in 1798 as part of the Township Act of 1798. It was occupied by the British in the winter of 1776–1777 during the Revolutionary War.[30]

The Declaration of Independence received one of its first public readings, by Col. John Neilson, in New Brunswick on July 9, 1776, in the days following its promulgation by the Continental Congress.[31][32][33]

The Trustees of Queen's College (now Rutgers University), founded in 1766, voted to locate the young college in New Brunswick, selecting the city over Hackensack, in Bergen County, New Jersey. Classes began in 1771 with one instructor, one sophomore, Matthew Leydt, and several freshmen at a tavern called the 'Sign of the Red Lion' on the corner of Albany and Neilson Streets (now the grounds of the Johnson & Johnson corporate headquarters). The Sign of the Red Lion was purchased on behalf of Queens College in 1771, and later sold to the estate of Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh in 1791.[34] Classes were held through the American Revolution in various taverns and boarding houses, and at a building known as College Hall on George Street, until Old Queens was erected in 1808.[35] It remains the oldest building on the Rutgers University campus.[36] The Queen's College Grammar School (now Rutgers Preparatory School) was established also in 1766, and shared facilities with the College until 1830, when it located in a building (now known as Alexander Johnston Hall) across College Avenue from Old Queens.[37] After Rutgers University became the state university of New Jersey in 1945,[38] the Trustees of Rutgers divested itself of Rutgers Preparatory School, which relocated in 1957 to an estate purchased from the Colgate-Palmolive Company in Franklin Township in neighboring Somerset County.[39]

The New Brunswick Theological Seminary, founded in 1784 in New York, moved to New Brunswick in 1810, sharing its quarters with the fledgling Queen's College. (Queen's closed from 1810 to 1825 due to financial problems, and reopened in 1825 as Rutgers College.)[40] The Seminary, due to overcrowding and differences over the mission of Rutgers College as a secular institution, moved to tract of land covering 7 acres (2.8 ha) located less than one-half mile (800 m) west, which it still occupies, although the land is now in the middle of Rutgers University's College Avenue campus.

New Brunswick was formed by royal charter on December 30, 1730, within other townships in Middlesex and Somerset counties and was reformed by royal charter with the same boundaries on February 12, 1763, at which time it was divided into north and south wards. New Brunswick was incorporated as a city by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on September 1, 1784.[29]

Old Queens, the oldest building at Rutgers University

Building the Streetcar line, around 1885

Albany Street Bridge, 1903

Aerial view of New Brunswick, 1910

African American community

Slavery in New Brunswick

The existence of an African American community in New Brunswick dates back to the 18th century, when racial slavery was a part of life in the city and the surrounding area. Local slaveholders routinely bought and sold African American children, women, and men in New Brunswick in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. In this period, the Market-House was the center of commercial life in the city. It was located at the corner of Hiram Street and Queen Street (now Neilson Street) adjacent to the Raritan Wharf. The site was a place where residents of New Brunswick sold and traded their goods which made it an integral part of the city's economy. The Market-House also served as a site for regular slave auctions and sales.[41]:101

By the late-eighteenth century, New Brunswick also became a hub for newspaper production and distribution. The Fredonian, a popular newspaper, was located less than a block away from the aforementioned Market-House and helped facilitate commercial transactions. A prominent part of the local newspapers were sections dedicated to private owners who would advertise their slaves for sale. The trend of advertising slave sales in newspapers shows that the New Brunswick residents typically preferred selling and buying slaves privately and individually rather than in large groups.[41]:103 The majority of individual advertisements were for female slaves, and their average age at the time of the sale was 20 years old, which was considered the prime age for childbearing. Slave owners would get the most profit from the women who fit into this category because these women had the potential to reproduce another generation of enslaved workers. Additionally, in the urban environment of New Brunswick, there was a high demand for domestic labor, and female workers were preferred for cooking and housework tasks.[41]:107

The New Jersey legislature passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1804.[42] Under the provisions of this law, children born to enslaved women after July 4, 1804, would serve their master for a term of 21 years (for girls) or a term of 25 years (for boys), and after this term, they would gain their freedom. However, all individuals who were enslaved before July 4, 1804, would continue to be slaves for life and would never attain freedom under this law. New Brunswick continued to be home to enslaved African Americans alongside a growing community of free people of color. The 1810 United States Census listed 53 free Blacks and 164 slaves in New Brunswick.[43]

African American spaces and institutions in the early 19th century

By the 1810s, some free African Americans lived in a section of the city called Halfpenny Town, which was located along the Raritan River by the east side of the city, near Queen (now Neilson) Street. Halfpenny Town was a place populated by free blacks and poorer white people who did not own slaves. This place was known as a social gathering for free blacks that was not completely influenced by white scrutiny and allowed free blacks to socialize among themselves. This does not mean that it was free from white eyes and was still under the derogatory effects of the slavery era.[41]:99 In the early decades of the nineteenth century, White and either free or enslaved African Americans shared many of the same spaces in New Brunswick, particularly places of worship. The First Presbyterian Church, Christ Church, and First Reformed Church were popular among both Whites and Blacks, and New Brunswick was notable for its lack of spaces where African Americans could congregate exclusively. Most of the time Black congregants of these churches were under the surveillance of Whites.[41]:113 That was the case until the creation of the African Association of New Brunswick in 1817.[41]:114–115

Both free and enslaved African Americans were active in the establishment of the African Association of New Brunswick, whose meetings were first held in 1817.[41]:112 The African Association of New Brunswick held a meeting every month, mostly in the homes of free blacks. Sometimes these meetings were held at the First Presbyterian Church. Originally intended to provide financial support for the African School of New Brunswick, the African Association grew into a space where blacks could congregate and share ideas on a variety of topics such as religion, abolition and colonization. Slaves were required to obtain a pass from their owner in order to attend these meetings. The African Association worked closely with Whites and was generally favored amongst White residents who believed it would bring more racial peace and harmony to New Brunswick.[41]:114–115

The African Association of New Brunswick decided to establish the African School in 1822. The African School was first hosted in the home of Caesar Rappleyea in 1823.[41]:114 The school was located on the upper end of Church Street in the downtown area of New Brunswick about two blocks away from the jail that held escaped slaves. Both free and enslaved Blacks were welcome to be members of the School.[41]:116 Reverend Huntington (pastor of the First Presbyterian Church) and several other prominent Whites were trustees of the African Association of New Brunswick. These trustees supported the Association which made some slave owners feel safe sending their slaves there by using a permission slip process.[41]:115 The main belief of these White supporters was that Blacks were still unfit for American citizenship and residence, and some trustees were connected with the American Colonization Society that advocated for the migration of free African Americans to Africa. The White trustees only attended some of the meetings of the African Association, and the Association was still unprecedented as a space for both enslaved and free Blacks to get together while under minimal supervision by Whites.[41]:116–117

The African Association appears to have disbanded after 1824. By 1827, free and enslaved Black people in the city, including Joseph and Jane Hoagland, came together to establish the Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church and purchased a plot of land on Division Street for the purpose of erecting a church building. This was the first African American church in Middlesex County. The church had approximately 30 members in its early years. The church is still in operation and is currently located at 39 Hildebrand Way.[44]

Records from the April 1828 census, conducted by the New Brunswick Common Council, state that New Brunswick was populated with 4,435 white residents and 374 free African Americans. The enslaved population of New Brunswick in 1828 consisted of 57 slaves who must serve for life and 127 slaves eligible for manumission at age 21 or 25 due to the 1804 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. Free and enslaved African Americans made up 11 percent of New Brunswick's population in 1828, a relatively high percentage for New Jersey.[41]:94 By comparison, as of the 1830 U.S. census, African Americans made up approximately 6.4% of the total population of New Jersey.[45]

Jail and curfew in the 19th century

In 1824, the New Brunswick Common Council adopted a curfew for free people of color. Free African Americans were not allowed to be out after 10 PM on Saturday night. The Common Council also appointed a committee of white residents who were charged with rounding up and detaining free African Americans who appeared to be out of place according to white authorities.[41]:98

New Brunswick became a notorious city for slave hunters, who sought to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Strategically located on the Raritan River, the city was also a vital hub for New Jersey's Underground Railroad. For runaway slaves in New Jersey, it served as a favorable route for those heading to New York and Canada. When African Americans tried to escape either to or from New Brunswick, they had a high likelihood of getting discovered and captured and sent to New Brunswick's gaol (pronounced "jail"), which was located on Prince Street, which by now is renamed Bayard Street.[41]:96

Hungarian community

The Committee of Hungarian Churches and Organizations of New Brunswick commemorating the anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

New Brunswick began attracting a Hungarian immigrant population around the turn of the 20th century. Hungarians were primarily attracted to the city by employment at Johnson & Johnson factories located in the city. Hungarians settled mainly in what today is the Fifth Ward.

The immigrant population grew until the end of the early century immigration boom. During the Cold War, the community was revitalized by the decision to house refugees from the failed 1956 Hungarian Revolution at Camp Kilmer, in nearby Edison. Even though the Hungarian population has been largely supplanted by newer immigrants, there continues to be a Hungarian Festival in the city held on Somerset Street on the first Saturday of June each year. Many Hungarian institutions set up by the community remain and active in the neighborhood, including: Magyar Reformed Church, Ascension Lutheran Church, St. Ladislaus Roman Catholic Church, St. Joseph Byzantine Catholic Church, Hungarian American Athletic Club, Aprokfalva Montessori Preschool, Széchenyi Hungarian Community School & Kindergarten, Teleki Pál Scout Home, Hungarian American Foundation, Vers Hangja, Hungarian Poetry Group, Bolyai Lecture Series on Arts and Sciences, Hungarian Alumni Association, Hungarian Radio Program, Hungarian Civic Association, Committee of Hungarian Churches and Organizations of New Brunswick, and Csűrdöngölő Folk Dance Ensemble.

Several landmarks in the city also testify to its Hungarian heritage. There is a street and a recreation park named after Lajos Kossuth, the famous leader of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. The corner of Somerset Street and Plum Street is named Mindszenty Square where the first ever statue of Cardinal Joseph Mindszenty was erected. A stone memorial to the victims of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution also stands nearby.

Latino community

About 50% of New Brunswick's population is self-identified as Hispanic, the 14th highest percentage among municipalities in New Jersey.[9][46] Since the 1960s, many of the new residents of New Brunswick have come from Latin America. Many citizens moved from Puerto Rico in the 1970s. In the 1980s, many immigrated from the Dominican Republic, and still later from Guatemala, Honduras, Ecuador and Mexico.

Demolition, revitalization and redevelopment

The Gateway Project under construction

College Avenue old and new

New Brunswick contains a number of examples of urban renewal in the United States. In the 1960s-1970s, the downtown area became blighted as middle class residents moved to newer suburbs surrounding the city, an example of the phenomenon known as "white flight." Beginning in 1975, Rutgers University, Johnson & Johnson and the local government collaborated through the New Jersey Economic Development Authority to form the New Brunswick Development Company (DevCo), with the goal of revitalizing the city center and redeveloping neighborhoods considered to be blighted and dangerous (via demolition of existing buildings and construction of new ones).[47] Johnson & Johnson decided to remain in New Brunswick and built a new world headquarters building in the area between Albany Street, Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, Route 18, and George Street, requiring many old buildings and historic roads to be removed. The Hiram Market area, a historic district that by the 1970s had become a mostly Puerto Rican and Dominican-American neighborhood, was demolished to build a Hyatt hotel and conference center, and upscale housing.[48] Johnson & Johnson guaranteed Hyatt Hotels' investment as they were wary of building an upscale hotel in a run-down area.

Devco, the hospitals, and the city government have drawn ire from both historic preservationists, those opposing gentrification[49] and those concerned with eminent domain abuses and tax abatements for developers.[50]

New Brunswick is one of nine cities in New Jersey designated as eligible for Urban Transit Hub Tax Credits by the state's Economic Development Authority. Developers who invest a minimum of $50 million within a half-mile of a train station are eligible for pro-rated tax credit.[51][52]

The Gateway tower, a 22-story redevelopment project next to the train station, was completed in 2012. The structure consists of apartments and condominiums (named "The Vue") built above a multi-story parking structure with a bridge connecting it to the station.[53] Boraie Development, a real estate development firm based in New Brunswick, has developed projects using the incentive.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 5.789 square miles (14.995 km2), including 5.227 square miles (13.539 km2) of land and 0.562 square miles (1.456 km2) of water (9.71%).[1][2] New Brunswick is in Raritan Valley (a line of cities in central New Jersey). New Brunswick is on the south side of Raritan Valley along with Piscataway Township, Highland Park, Edison Township, and Franklin Township (Somerset County). New Brunswick lies southwest of Newark and New York City and northeast of Trenton and Philadelphia.

New Brunswick is bordered by Piscataway, Highland Park and Edison across the Raritan River to the north by way of the Donald and Morris Goodkind Bridges, and also by North Brunswick Township to the southwest, East Brunswick Township to the southeast, and Franklin Township.[54]

While the city does not hold elections based on a ward system it has been so divided.[55][56][57] There are several neighborhoods in the city, which include the Fifth Ward, Feaster Park, Lincoln Park,[citation needed][58]Raritan Gardens, and Edgebrook-Westons Mills.[55]

Climate

New Brunswick has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) typical to New Jersey, characterized by humid, hot summers and moderately cold winters with moderate to considerable rainfall throughout the year. There is no marked wet or dry season.

| Climate data for New Brunswick, New Jersey | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 39.2 (4.0) | 42.4 (5.8) | 50.5 (10.3) | 61.7 (16.5) | 71.7 (22.1) | 80.8 (27.1) | 85.6 (29.8) | 83.9 (28.8) | 77.3 (25.2) | 66.0 (18.9) | 55.4 (13.0) | 44.1 (6.7) | 63.3 (17.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 21.8 (−5.7) | 23.6 (−4.7) | 30.5 (−0.8) | 40.2 (4.6) | 49.7 (9.8) | 60.0 (15.6) | 64.9 (18.3) | 63.5 (17.5) | 55.1 (12.8) | 42.9 (6.1) | 35.5 (1.9) | 27.1 (−2.7) | 43.0 (6.1) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.62 (92) | 2.87 (73) | 4.18 (106) | 4.23 (107) | 4.19 (106) | 4.41 (112) | 5.08 (129) | 4.15 (105) | 4.51 (115) | 3.80 (97) | 3.83 (97) | 4.06 (103) | 48.93 (1,242) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.0 (20) | 9.2 (23) | 4.5 (11) | 0.9 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.25) | 0.5 (1.3) | 5.2 (13) | 28.4 (70.85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.7 | 9.2 | 10.5 | 11.8 | 12.2 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 122.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 13.5 |

| Source: NOAA[59][60] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 5,866 | — | |

| 1850 | 10,019 | 70.8% | |

| 1860 | 11,256 | 12.3% | |

| 1870 | 15,058 | 33.8% | |

| 1880 | 17,166 | 14.0% | |

| 1890 | 18,603 | 8.4% | |

| 1900 | 20,005 | 7.5% | |

| 1910 | 23,388 | 16.9% | |

| 1920 | 32,779 | 40.2% | |

| 1930 | 34,555 | 5.4% | |

| 1940 | 33,180 | −4.0% | |

| 1950 | 38,811 | 17.0% | |

| 1960 | 40,139 | 3.4% | |

| 1970 | 41,885 | 4.3% | |

| 1980 | 41,442 | −1.1% | |

| 1990 | 41,711 | 0.6% | |

| 2000 | 48,573 | 16.5% | |

| 2010 | 55,181 | 13.6% | |

| Est. 2016 | 56,910 | [12][61] | 3.1% |

| Population sources: 1860–1920[62] 1840–1890[63] 1850–1870[64] 1850[65] 1870[66] 1880–1890[67] 1890–1910[68] 1860–1930[69] 1930–1990[70] 2000[71][72] 2010[9][10][11] | |||

Census 2010

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 55,181 people, 14,119 households, and 7,751 families residing in the city. The population density was 10,556.4 per square mile (4,075.8/km2). There were 15,053 housing units at an average density of 2,879.7 per square mile (1,111.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 45.43% (25,071) White, 16.04% (8,852) Black or African American, 0.90% (498) Native American, 7.60% (4,195) Asian, 0.03% (19) Pacific Islander, 25.59% (14,122) from other races, and 4.39% (2,424) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 49.93% (27,553) of the population.[9]

There were 14,119 households out of which 31.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.2% were married couples living together, 17.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.1% were non-families. 25.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.36 and the average family size was 3.91.[9]

In the city, the population was spread out with 21.1% under the age of 18, 33.2% from 18 to 24, 28.4% from 25 to 44, 12.2% from 45 to 64, and 5.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 23.3 years. For every 100 females there were 105.0 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 105.3 males.[9]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $44,543 (with a margin of error of +/- $2,356) and the median family income was $44,455 (+/- $3,526). Males had a median income of $31,313 (+/- $1,265) versus $28,858 (+/- $1,771) for females. The per capita income for the borough was $16,395 (+/- $979). About 15.5% of families and 25.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.4% of those under age 18 and 16.9% of those age 65 or over.[73]

Census 2000

As of the 2000 United States Census, there were 48,573 people, 13,057 households, and 7,207 families residing in the city. The population density was 9,293.5 per square mile (3,585.9/km2). There were 13,893 housing units at an average density of 2,658.1 per square mile (1,025.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.7% White, 24.5% African American, 1.2% Native American, 5.9% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 21.0% from other races, and 4.2% from two or more races. 39.01% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[71][72]

There were 13,057 households of which 29.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.6% were married couples living together, 18.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.8% were non-families. 24.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.23 and the average family size was 3.69.[71][72]

20.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 34.0% from 18 to 24, 28.1% from 25 to 44, 11.3% from 45 to 64, and 6.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 24 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.8 males.[71][72]

The median household income in the city was $36,080, and the median income for a family was $38,222. Males had a median income of $25,657 versus $23,604 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,308. 27.0% of the population and 16.9% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total people living in poverty, 25.9% were under the age of 18 and 13.8% were 65 or older.[71][72]

Economy

Health care

City Hall has promoted the nickname "The Health Care City" to reflect the importance of the healthcare industry to its economy.[74] The city is home to the world headquarters of Johnson & Johnson, along with several medical teaching and research institutions including Saint Peter's University Hospital, Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital and the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, the Cancer Institute of New Jersey, and The Bristol-Myers Squibb Children's Hospital.[75] There is also a public high school in New Brunswick focused on health sciences, the New Brunswick Health Sciences Technology High School.[76]

Urban Enterprise Zone

Portions of the city are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone, one of 27 zones in the state. In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (versus the 6.625% rate charged statewide, effective January 1, 2018) at eligible merchants.[77][78][79] Established in 2004, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in December 2024.[80][81]

Arts and culture

Theatre

Three neighboring professional venues, Crossroads Theatre designed by Parsons+Fernandez-Casteleiro Architects from New York. In 1999, the Crossroads Theatre won the prestigious Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre. Crossroads is the first African American theater to receive this honor in the 33-year history of this special award category.[82] There is also George Street Playhouse, and the State Theatre, which form the heart of the local theatre scene. Crossroad Theatre houses American Repertory Ballet and the Princeton Ballet School. Rutgers University has a number of student companies that perform everything from cabaret acts to Shakespeare and musical productions.

Looking north from the corner of New and George Streets. The Heldrich Center is on the left.

Museums

New Brunswick is the site of the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (founded in 1966),[83]Albus Cavus, and the Rutgers University Geology Museum (founded in 1872).[84]

Fine arts

New Brunswick was an important center for avant-garde art in the 1950s-70s with several artists such as Allan Kaprow, George Segal, George Brecht, Robert Whitman, Robert Watts, Lucas Samaras, Geoffrey Hendricks, Wolf Vostell and Roy Lichtenstein; some of whom taught at Rutgers University. This group of artists was sometimes referred to as the 'New Jersey School' or the 'New Brunswick School of Painting'. The YAM Festival was venue on May 19, 1963 to actions and Happenings. For more information, see Fluxus at Rutgers University.[85][86]

Grease trucks

The "Grease Trucks" at Rutgers University's College Avenue campus

The "Grease Trucks" were a group of truck-based food vendors located on the College Avenue campus of Rutgers University. They were known for serving "Fat Sandwiches," sub rolls containing several ingredients such as steak, chicken fingers, French fries, falafel, cheeseburgers, mozzarella sticks, gyro meat, bacon, eggs and marinara sauce. In 2013 the grease trucks were removed for the construction of a new Rutgers building and were forced to move into various other areas of the Rutgers-New Brunswick Campus.[87]

Music

New Brunswick's bar scene has been the home to many original rock bands, including some which went on to national prominence such as The Smithereens and Bon Jovi, as well as a center for local punk rock and underground music. Many alternative rock bands got radio airplay thanks to Matt Pinfield who was part of the New Brunswick music scene for over 20 years at Rutgers University radio station WRSU. Local pubs and clubs hosted many local bands, including the Court Tavern[88] until 2012[89] (since reopened),[90] and the Melody Bar during the 1980s and 1990s. As the New Brunswick basement scene grows in popularity, it was ranked the number 4 spot to see Indie bands in New Jersey.[91] In March 2017, NewJersey.com wrote that "even if Asbury Park has recently returned as our state's musical nerve center, with the brick-and-mortar venues and infrastructure to prove it, New Brunswick remains as the New Jersey scene's unadulterated, pounding heart."[92]

Government

New Brunswick City Hall, the New Brunswick Free Public Library, and the New Brunswick Main Post Office are located in the city's Civic Square government district, as are numerous other city, county, state, and federal offices.

Local government

City Hall

The City of New Brunswick is governed within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government. The governing body consists of a mayor and a five-member City Council, all elected at-large in partisan elections to four-year terms of office in even years as part of the November general election. The City Council's five members are elected on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election every other year. As the legislative body of New Brunswick's municipal government, the City Council is responsible for approving the annual budget, ordinances and resolutions, contracts, and appointments to boards and commissions. The Council President, elected to a two-year term by the members of the Council, presides over all meetings.[7]

As of 2018[update], Democrat James Cahill is the 62nd Mayor of New Brunswick; he was sworn in as Mayor on January 1, 1991 and is serving a term that expires on December 31, 2018.[3] Members of the City Council are Council President Glenn J. Fleming Sr. (D, 2020), Council Vice President John A. Andersen (D, 2020), Kevin P. Egan (D, 2018), Rebecca H. Escobar (D, 2018) and Suzanne M. Sicora Ludwig (D, 2020).[93][94][95][96][97]

Police department

The New Brunswick police department has received attention for various incidents over the years. In 1991, the fatal shooting of Shaun Potts, an unarmed black resident, by Sergeant Zane Grey led to multiple local protests.[98] In 1996, Officer James Consalvo fatally shot Carolyn "Sissy" Adams, an unarmed prostitute who had bit him.[99] The Adams case sparked calls for reform in the New Brunswick police department, and ultimately was settled with the family.[100] Two officers, Sgt. Marco Chinchilla and Det. James Marshall, were convicted of running a bordello in 2001. Chinchilla was sentenced to three years and Marshall was sentenced to four.[101] In 2011, Officer Brad Berdel fatally shot Barry Deloatch, a black man who had run from police (although police claim he struck officers with a stick);[102] this sparked daily protests from residents.[103]

Following the Deloatch shooting, sergeant Richard Rowe was formally charged with mishandling 81 Internal Affairs investigations; Mayor Cahill explained that this would help "rebuild the public's trust and confidence in local law enforcement."[104]

Federal, state and county representation

New Brunswick is located in the 6th Congressional District[105] and is part of New Jersey's 17th state legislative district.[10][106][107]

For the 116th United States Congress, New Jersey's Sixth Congressional District is represented by Frank Pallone (D, Long Branch).[108][109] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2021)[110] and Bob Menendez (Paramus, term ends 2025).[111][112]

For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 17th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Bob Smith (D, Piscataway) and in the General Assembly by Joseph Danielsen (D, Franklin Township, Somerset County) and Joseph V. Egan (D, New Brunswick).[113][114] The Governor of New Jersey is Phil Murphy (D, Middletown Township).[115] The Lieutenant Governor of New Jersey is Sheila Oliver (D, East Orange).[116]

Middlesex County is governed by a Board of Chosen Freeholders, whose seven members are elected at-large on a partisan basis to serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election each year as part of the November general election. At an annual reorganization meeting held in January, the board selects from among its members a Freeholder Director and Deputy Director. As of 2015[update], Middlesex County's Freeholders (with party affiliation, term-end year, residence and committee chairmanship listed in parentheses) are

Freeholder Director Ronald G. Rios (D, term ends December 31, 2015, Carteret; Ex-officio on all committees),[117]

Freeholder Deputy Director Carol Barrett Bellante (D, 2017; Monmouth Junction, South Brunswick Township; County Administration),[118]

Kenneth Armwood (D, 2016, Piscataway; Business Development and Education),[119]

Charles Kenny ( D, 2016, Woodbridge Township; Finance),[120]

H. James Polos (D, 2015, Highland Park; Public Safety and Health),[121]

Charles E. Tomaro (D, 2017, Edison; Infrastructure Management)[122] and

Blanquita B. Valenti (D, 2016, New Brunswick; Community Services).[123][124] Constitutional officers are

County Clerk Elaine M. Flynn (D, Old Bridge Township),[125]

Sheriff Mildred S. Scott (D, 2016, Piscataway)[126] and Surrogate

Kevin J. Hoagland (D, 2017; New Brunswick).[124][127]

Politics

As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 22,742 registered voters in New Brunswick, of which 8,732 (38.4%) were registered as Democrats, 882 (3.9%) were registered as Republicans and 13,103 (57.6%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 25 voters registered to other parties.[128]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

2016[129] | 14.1% 1,516 | 81.9% 8,776 | 4.0% 426 |

2012[130] | 14.3% 1,576 | 83.4% 9,176 | 2.2% 247 |

2008[131] | 14.8% 1,899 | 83.3% 10,717 | 1.1% 140 |

2004[132] | 19.7% 2,018 | 78.2% 8,023 | 1.4% 143 |

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 83.4% of the vote (9,176 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 14.3% (1,576 votes), and other candidates with 2.2% (247 votes), among the 11,106 ballots cast by the township's 23,536 registered voters (107 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 47.2%.[133][134] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 83.3% of the vote (10,717 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 14.8% (1,899 votes) and other candidates with 1.1% (140 votes), among the 12,873 ballots cast by the township's 23,533 registered voters, for a turnout of 54.7%.[131] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 78.2% of the vote (8,023 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush with 19.7% (2,018 votes) and other candidates with 0.7% (143 votes), among the 10,263 ballots cast by the township's 20,734 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 49.5.[132]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

2017[135] | 13.6% 590 | 83.1% 3,616 | 3.4% 148 |

2013[136] | 31.2% 1,220 | 66.5% 2,604 | 2.3% 92 |

2009[137] | 20.9% 1,314 | 68.2% 4,281 | 8.2% 515 |

2005[138] | 17.2% 880 | 76.9% 3,943 | 4.2% 214 |

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 66.5% of the vote (2,604 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 31.2% (1,220 votes), and other candidates with 2.3% (92 votes), among the 3,991 ballots cast by the township's 23,780 registered voters (75 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 16.8%.[139][140] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 68.2% of the vote (4,281 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 20.9% (1,314 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 6.2% (387 votes) and other candidates with 2.0% (128 votes), among the 6,273 ballots cast by the township's 22,534 registered voters, yielding a 27.8% turnout.[137]

Education

Public schools

The New Brunswick Public Schools serve students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade. The district is one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide,[141] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[142][143] The district's nine-member Board of Education is elected at large, with three members up for election on a staggered basis each April to serve three-year terms of office; until 2012, the members of the Board of Education were appointed by the city's mayor.[144]

As of the 2014-15 school year, the district and its 10 schools had an enrollment of 10,230 students and 724.5 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 14.1:1.[145] Schools in the district (with 2014-15 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[146]) are

Lincoln Elementary School[147] / Lincoln Annex School[148] (grades PreK-5; 711 students),

Livingston Elementary School[149] (K-5; 581),

McKinley Community Elementary School[150] (PreK-8; 876),

A. Chester Redshaw Elementary School[151] (PreK-5; 781),

Paul Robeson Community School For The Arts[152] (PreK-5; 575),

Roosevelt Elementary School[153] (PreK-5; 878),

Lord Stirling Elementary School[154] (PreK-5; 643),

Woodrow Wilson Elementary School[155] (PreK-8; 443),

New Brunswick Middle School[156] (6-8; 1,365),

New Brunswick High School[157] (9-12; 1,765) and

Health Sciences Technology High School[158] (9-12; NA).[159][160]

The community is also served by the Greater Brunswick Charter School, a K-8 charter school with an enrollment of about 250 children from New Brunswick, Highland Park, Edison and other area communities.[161]

Higher education

Rutgers University has three campuses in the city: College Avenue Campus (seat of the University), Douglass Campus, and Cook Campus, which extend into surrounding townships. Rutgers has also added several buildings downtown in the last two decades, both academic and residential.[162]

- New Brunswick is the site to the New Brunswick Theological Seminary, a seminary of the Reformed Church in America, that was founded in New York in 1784, then moved to New Brunswick in 1810.[40]

Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, part of Rutgers University, is located in New Brunswick and Piscataway.[163]

Middlesex County College has some facilities downtown, though its main campus is in Edison.[164]

Transportation

Roads and highways

The New Jersey Turnpike (I-95) in New Brunswick

As of May 2010[update], the city had 73.24 miles (117.87 km) of roadways, of which 56.13 miles (90.33 km) were maintained by the municipality, 8.57 miles (13.79 km) by Middlesex County, 7.85 miles (12.63 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 0.69 miles (1.11 km) by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority.[165]

The city encompasses the intersection of U.S. Route 1 and Route 18, and is bisected by Route 27. New Brunswick hosts less than a mile of the New Jersey Turnpike (Interstate 95). A few turnpike ramps are in the city that lead to Exit 9 which is just outside the city limits in East Brunswick Township.

Other major roads that are nearby include the Garden State Parkway in Woodbridge Township and Interstate 287 in neighboring Edison, Piscataway and Franklin townships.

New Brunswick Parking Authority manages 14 ground-level and multi-story parking facilities across the city.[166][167] CitiPark manages a downtown parking facility at 2 Albany Street.[168][169]

Public transportation

Southbound platform of New Brunswick's NJ Transit train station. University Center at Easton Avenue is in the background.

Panorama of New Brunswick station track to New York City

New Brunswick is served by NJ Transit and Amtrak trains on the Northeast Corridor Line.[170]NJ Transit provides frequent service north to Pennsylvania Station, in Midtown Manhattan, and south to Trenton, while Amtrak's Keystone Service and Northeast Regional trains service the New Brunswick station.[171] The Jersey Avenue station is also served by Northeast Corridor trains.[172] For other Amtrak connections, riders can take NJ Transit to Penn Station (New York or Newark), Trenton, or Metropark.

Local bus service is provided by NJ Transit's 810, 811, 814, 815, 818 routes and 980 route,[173] the extensive Rutgers Campus bus network,[174] the MCAT/BrunsQuiDASHck shuttle system,[175] DASH/CAT buses,[176] and NYC bound Suburban Trails buses.[177] Studies are being conducted to create the New Brunswick Bus Rapid Transit system.

Intercity bus service from New Brunswick to Columbia, Maryland and Washington, DC is offered by OurBus Prime.[178]

New Brunswick was at the eastern terminus of the Delaware and Raritan Canal, of which there are remnants surviving or rebuilt along the river.[179] Until 1936, the city was served by the interurban Newark–Trenton Fast Line.

Popular culture

- On April 18, 1872, at New Brunswick, William Cameron Coup developed the system of loading circus equipment and animals on railroad cars from one end and through the train, rather than from the sides. This system would be adopted by other railroad circuses and used through the golden age of railroad circuses and even by the Ringling shows today.[citation needed]

- The 1980s sitcom, Charles in Charge, was set in New Brunswick.[180]

- The 2004 movie Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle revolves around Harold and Kumar's attempt to get to a White Castle restaurant and includes a stop in a fictionalized New Brunswick.[181]

Points of interest

The Heldrich in Downtown New Brunswick

Albany Street Bridge across the Raritan River to Highland Park

Bishop House,[182] 115 College Avenue, a mansion of the Italianate style of architecture, was built for James Bishop. Placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Old Queens, built in 1809, is the oldest building at Rutgers University.

Buccleuch Mansion in Buccleuch Park- Historic Christ Church Episcopal Churchyard, New Brunswick

- The Henry Guest House

William H. Johnson House c. 1870

St. Peter The Apostle Church, built in 1856 and located at 94 Somerset Street.- Delaware and Raritan Canal

- The historic Old Queens Campus and Voorhees Mall at Rutgers University

- Birthplace of poet Joyce Kilmer

- Kilmer Square, a retail/commercial complex on Albany Street

- Site of Johnson & Johnson world headquarters

Rutgers Gardens (in nearby North Brunswick)- The Willow Grove Cemetery near downtown

- Grave of Mary Ellis (1750–1828). This grave stands out due to its location in the AMC Theatres parking lot on U.S. Route 1 downriver from downtown New Brunswick.

Lawrence Brook, a tributary of the Raritan River.

Elmer B. Boyd Park, a park running along the Raritan River, adjacent to Route 18.

The Hungarian American Athletic Club, a Hungarian community building on the corner of Somerset street and Harvey street.

Places of worship

- Abundant Life Family Worship Church - founded in 1991.[183]

- Anshe Emeth Memorial Temple (Reform Judaism) - established in 1859.[184]

- Ascension Lutheran Church - founded in 1908 as The New Brunswick First Magyar Augsburg Evangelical Church.[185]

Christ Church, Episcopal - granted a royal charter in 1761.[186]

- Ebenezer Baptist Church

- First Baptist Church of New Brunswick, American Baptist

First Presbyterian, Presbyterian (PCUSA)

First Reformed Reformed (RCA)

Kirkpatrick Chapel at Rutgers University (nondenominational)- Magyar Reformed, Calvinist

- Mount Zion AME (African Methodist Episcopal)

- Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church

- Point Community Church

- Saint Joseph, Byzantine Catholic

- Saint Ladislaus, Roman Catholic

- Saint Mary of Mount Virgin Church, Remsen Avenue and Sandford Street, Roman Catholic

- Sacred Heart Church, Throop Avenue, Roman Catholic

Saint Peter the Apostle Church, Somerset Street, Roman Catholic- Second Reformed Church, Reformed (RCA)

- Sharon Baptist Church

United Methodist Church at New Brunswick

Voorhees Chapel at Rutgers University (nondenominational)

Notable people

Actor Michael Douglas

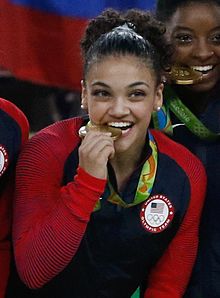

Gymnast Laurie Hernandez at the 2016 Summer Olympics

R&B singer Jaheim

Phil Radford, former executive director of Greenpeace USA

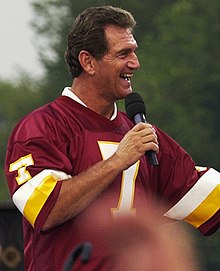

Former NFL quarterback Joe Theismann

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with the City of New Brunswick include:

David Abeel (1804–1846), Dutch Reformed Church missionary.[187]

Garnett Adrain (1815–1878), member of the United States House of Representatives.[188]

Charlie Atherton (1874–1934), major league baseball player.[189]

Jim Axelrod, national correspondent for CBS News, and reports for the CBS Evening News.[190]

Catherine Hayes Bailey (1921–2014), plant geneticist who specialized in fruit breeding.[191]

Joe Barzda (1915–1993), race car driver.[192][193]

John Bayard (1738–1807), merchant, soldier and statesman who was a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress in 1785 and 1786, and later mayor of New Brunswick.[194]

John Bradbury Bennet (1865–1940), United States Army officer and brigadier general active during World War I.[195]

James Berardinelli (born 1967), film critic.[196][197]

James Bishop (1816–1895), represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1855 to 1857.[198]

Charles S. Boggs (1811–1877), Rear Admiral who served in the United States Navy during the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War.[199]

PJ Bond, singer-songwriter.[200]

Jake Bornheimer (1927–1986), professional basketball player for the Philadelphia Warriors.[201]

Brett Brackett (born 1987), football tight end.[202]

Derrick Drop Braxton (born 1981), record producer and composer.[203]

Sherry Britton (1918–2008), burlesque performer and actress.[204]

Gary Brokaw (born 1954), former professional basketball player who played most of his NBA career for the Milwaukee Bucks.[205]

Jalen Brunson (born 1996), basketball player.[206]

William Burdett-Coutts (1851–1921), British Conservative politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1885 to 1921.[207]

Arthur S. Carpender (1884–1960), United States Navy admiral who commanded the Allied Naval Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area during World War II.[208]

Jonathan Casillas (born 1987), linebacker for the NFL's New Orleans Saints and University of Wisconsin.[209]

Joseph Compton Castner (1869–1946), Army general[210]

Wheeler Winston Dixon (born 1950), filmmaker, critic, and author.[211][212]

Michael Douglas (born 1944), actor.[213]

Linda Emond (born 1959), actress.[214]

Jerome Epstein (born 1937), politician who served in the New Jersey Senate from 1972 to 1974 and later went to federal prison for pirating millions of dollars worth of fuel oil.[215]

Anthony Walton White Evans (1817–1886), engineer.[216]

Mervin Field (1921–2015), pollster of public opinion.[217]

Louis Michael Figueroa (born 1966), arguably the most prolific transcontinental journeyman.[218]

Margaret Kemble Gage (1734–1824). wife of General Thomas Gage, who led the British Army in Massachusetts early in the American Revolutionary War and who may have informed the revolutionaries of her husband's strategy.[219]

Morris Goodkind (c. 1888–1968), chief bridge engineer for the New Jersey State Highway Department from 1925 to 1955 (now the New Jersey Department of Transportation), responsible for the design of the Pulaski Skyway and 4,000 other bridges.[220]

Vera Mae Green (1928–1982), anthropologist, educator and scholar, who made major contributions in the fields of Caribbean studies, interethnic studies, black family studies and the study of poverty and the poor.[221]

Alan Guth (born 1947), theoretical physicist and cosmologist.[222]

- All involved in the Hall-Mills Murder case of the 1920s.[223]

Augustus A. Hardenbergh (1830–1889), represented New Jersey's 7th congressional district from 1875 to 1879, and again from 1881 to 1883.[224]

Mel Harris (born 1956), actress.[225]

Mark Helias (born 1950), jazz bassist / composer.[226]

Laurie Hernandez (born 2000), artistic gymnast representing Team USA at the 2016 Summer Olympics.[227]

Sabah Homasi (born 1988), mixed martial artist who competes in the welterweight division.[228]

Christine Moore Howell (1899–1972), hair care product businesswoman who founded Christine Cosmetics.[229]

Adam Hyler (1735–1782), privateer during the American Revolutionary War.[230]

Jaheim (born 1978, full name Jaheim Hoagland), R&B singer.[231]

Dwayne Jarrett (born 1986), wide receiver for the University of Southern California football team 2004 to 2006, current WR drafted by the Carolina Panthers.[232]

James P. Johnson (1891–1955), pianist and composer who was one of the original stride piano masters.[233]

William H. Johnson (1829–1904), painter and wallpaper hanger, businessman and local crafts person, whose home (c. 1870) was placed on the State of New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places in 2006.[234]

Robert Wood Johnson I (1845–1910), businessman who was one of the founders of Johnson & Johnson.[235]

Robert Wood Johnson II (1893–1968), businessman who led Johnson & Johnson and served as mayor of Highland Park, New Jersey.[236]

Woody Johnson (born 1947), businessman, philanthropist, and diplomat who is currently serving as United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom.[237]

Mary Lea Johnson Richards (1926–1990), heiress, entrepreneur and Broadway producer, who was the first baby to appear on a Johnson's baby powder label.[238]

Joyce Kilmer (1886–1918), poet.[239]

Littleton Kirkpatrick (1797–1859), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1853 to 1855, and was mayor of New Brunswick in 1841 and 1842.[240]

Ted Kubiak (born 1942), MLB player for the Kansas City/Oakland Athletics, Milwaukee Brewers, St. Louis Cardinals, Texas Rangers, and the San Diego Padres.[241]

Floyd Mayweather Jr. (born 1977), multi-division winning boxer, currently with an undefeated record of 50-0; he grew up in the 1980s in the Hiram Square neighborhood.[242]

Jim Norton (born 1968), comedian.[243]

Robert Pastorelli (1954–2004), actor known primarily for playing the role of the house painter on Murphy Brown.[244]

Stephen Porges (born 1945), Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.[245]

Franke Previte, composer.[246]

Phil Radford (born 1976), Greenpeace Executive Director.[citation needed]

Miles Ross (1827–1903), Mayor of New Brunswick, U.S. Representative and businessman.[247]

Gabe Saporta (born 1979), musician and frontman of bands Midtown and Cobra Starship.[248]

Jeff Shaara (born 1952), historical novelist.[249]

George Sebastian Silzer (1870–1940), served as the 38th Governor of New Jersey. Served on the New Brunswick board of aldermen from 1892 to 1896.[250]

James H. Simpson (1813–1883), U.S. Army surveyor of western frontier areas.[251]

Arthur Space (1908–1983), actor of theatre, film, and television.[252]

Larry Stark (born 1932), theater reviewer and creator of Theater Mirror.[253]

Ron "Bumblefoot" Thal (born 1969), guitarist, musician, composer.[254]

Joe Theismann (born 1949), former professional quarterback who played in the NFL for the Washington Redskins and former commentator on ESPN's Monday Night Football.[255]

William Henry Vanderbilt (1821–1885), businessman.[256]

John Van Dyke (1807–1878), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1847 to 1851, and served as Mayor of New Brunswick from 1846 to 1847.[257]

Paul Wesley (born 1982), actor, known for his role as "Stefan Salvatore" on The CW show The Vampire Diaries.[258]

Rev. Samuel Merrill Woodbridge (1819–1905), minister, author, professor at Rutgers College and New Brunswick Theological Seminary.[259]

Eric Young (born 1967), former Major League Baseball player.[260]

Eric Young Jr. (born 1985), Major League Baseball player.[261]

- All members of The Gaslight Anthem[262]

- All members of Streetlight Manifesto[263]

Sister cities

New Brunswick has four sister cities, as listed by Sister Cities International:[264][265]

Debrecen, Hajdú-Bihar, Hungary

Debrecen, Hajdú-Bihar, Hungary

Fukui City, Fukui, Japan

Fukui City, Fukui, Japan

Limerick, County Limerick, Ireland

Limerick, County Limerick, Ireland

Tsuruoka, Yamagata, Japan

Tsuruoka, Yamagata, Japan

See also

New Brunswick, New Jersey portal

New Brunswick, New Jersey portal

References

^ abcdef 2010 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey County Subdivisions, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2015.

^ ab US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

^ ab Mayor's Bio, City of New Brunswick. Accessed January 23, 2018.

^ 2017 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed May 30, 2017.

^ Department of Administration, City of New Brunswick. Accessed July 13, 2016.

^ City Clerk, City of New Brunswick. Accessed July 13, 2016.

^ ab 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 81.

^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: City of New Brunswick, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed March 8, 2013.

^ abcdefg DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for New Brunswick city, Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 18, 2012.

^ abcd Municipalities Grouped by 2011–2020 Legislative Districts, New Jersey Department of State, p. 8. Accessed January 6, 2013.

^ abc Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for New Brunswick city Archived 2014-01-17 at the Wayback Machine., New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed April 18, 2012.

^ abc PEPANNRES - Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 - 2016 Population Estimates for New Jersey municipalities, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 16, 2017.

^ ab GCT-PH1 Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - State -- County Subdivision from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 23, 2012.

^ Look Up a ZIP Code for New Brunswick, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed April 18, 2012.

^ Zip Codes, State of New Jersey. Accessed August 18, 2013.

^ Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for New Brunswick, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed October 6, 2014.

^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

^ Geographic codes for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed August 29, 2017.

^ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

^ Staff. "Lew Dockstader, Minstrel, Is Dead. Famous Comedian Succumbs to a Bone Tumor at His Daughter's Home at 68", The New York Times, October 27, 1924. Accessed May 18, 2015.

^ New Jersey County Map, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed July 10, 2017.

^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010 Archived 2013-05-20 at the Wayback Machine., New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed November 23, 2012.

^ "7:30 a.m.—Filling cracks in the health care city", Home News Tribune, September 23, 1999. "With two major hospitals and a medical school, New Brunswick proclaims itself The Healthcare City."

^ "A wet day in the Hub City", Home News Tribune, September 23, 1999. "A few days short of 60 years, on Wednesday, Sept. 16, a dreary, drizzly day just ahead of the deluge of Hurricane Floyd, the Home News Tribune sent 24 reporters, 9 photographers and one artist into the Hub City, as it is known, to take a peek into life in New Brunswick as it is in 1999."

^ Weiss, Jennifer. "REDEVELOPMENT; As New Brunswick Grows, City's Hungarians Adapt" Archived 2017-08-29 at the Wayback Machine., The New York Times, July 16, 2006. Accessed August 29, 2017. "While the Hungarian community has diminished over the years—in the 1930s it made up a third of New Brunswick's population—much of what it built remains."

^ Staff. "NEW-JERSEY.; Miscellaneous Notes about New-Brunswick.", The New York Times, July 27, 1854. Accessed August 29, 2017. "If the 'desperately hot' weather permit, I purpose to give you a few items of general interest respecting this ancient Dutch settlement. However, with the mercury ranging from 78° to 98° in the shade, during the sixteen hours of sunshine, you will not expect much exertion on my part. DANIEL COOPER (says GORDON,) was the first recorded inhabitant of 'Prigmore's Swamp.'"

^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed September 9, 2015.

^ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 223. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed September 9, 2015.

^ ab Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 171. Accessed March 26, 2012.

^ Revolutionary War Sites in New Brunswick, Revolutionary War New Jersey. Accessed August 18, 2013.

^ "Declaration of Independence: First Public Readings". www1.american.edu. Retrieved 27 September 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Harper's New Monthly Magazine, July 1892, 251

^ Lee, Eunice. "Statue of New Brunswick Revolutionary War figure planned", The Star-Ledger, July 31, 2011. Accessed August 18, 2013. "New Brunswick Public Sculpture, a nonprofit, is commissioning a life-size bronze statue of Col. John Neilson, a New Jersey native who gave one of the earliest readings of the Declaration of Independence on July 9, 1776, while standing before a crowd in New Brunswick."

^ Benedict, William H. (July 1918). "Early Taverns in New Brunswick". Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society. 3 (3): 136.

^ Fuentes, Marisa; White, Deborah (2016). Scarlet and Black: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

^ "Historic places" Archived 2014-08-16 at the Wayback Machine., Rutgers Focus, December 7, 2001. Accessed August 18, 2013.

^ Paths to Historic Rutgers: A Self-Guided Tour - Alexander Johnston Hall, Rutgers University. Accessed August 29, 2017. "Alexander Johnston Hall was built by Nicholas Wyckoff in 1830 to provide a home for the Rutgers Preparatory School, which had shared space in Old Queens with the College and New Brunswick Theological Seminary since 1811."

^ History, Rutgers University. Accessed July 13, 2016. "In 1945 and 1956, state legislative acts designated Rutgers as The State University of New Jersey, a public institution."

^ Rutgers College Grammar School, Rutgers University Common Repository. Accessed August 18, 2013. "The Rutgers Preparatory School remained in New Brunswick until 1957, when it moved to its current location in Somerset, N.J."

^ ab 2016-17 Academic Catalog, New Brunswick Theological Seminary. Accessed August 29, 2017. "In 1796, the school moved to Brooklyn and in 1810 to New Brunswick, to serve better the church and its candidates for ministry. Since 1856, New Brunswick Seminary has carried on its life and work on its present New Brunswick campus."

^ abcdefghijklmno Armstead, Shaun; Sutter, Brenann; Walker, Pamela; Wiesner, Caitlin (2016). ""And I Poor Slave Yet": The Precarity of Black Life in New Brunswick, 1766–1835". In Fuentes, Marisa; White, Deborah Gray. Scarlet and Black: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. JSTOR j.ctt1k3s9r0.9.

^ "An act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, Feb. 15, 1804". The Law of Slavery in New Jersey. New Jersey Digital Legal Library. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

^ New Jersey's African American Tour Guide, New Jersey Commerce and Economic Growth Commission. Accessed December 17, 2014. "At the southern edge of the Gateway Region is New Brunswick, a town with much culture to offer and African American history to explore. African Americans were living here as far back as 1790, and by 1810, the Census listed 53 free Blacks—and 164 slaves—out of the 469 families then living in town. One of the state's oldest Black churches, Mt. Zion A.M.E., at 25 Division Street, was founded in 1825."

^ Makin, Cheryl (2017-10-27). "Local AME churches celebrate spirituality, longevity". MY CENTRAL JERSEY. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

^ Wright, Giles R. (1989). "Appendix 3". Afro-Americans in New Jersey: a short history (PDF). Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Historical Commission.

^ Mascarenhas, Rohan. "Census data shows Hispanics as the largest minority in N.J.", The Star-Ledger, February 3, 2011. Accessed June 24, 2013.

^ "Devco spends $1.6 billion since 1970s", The Daily Targum, January 25, 2006, backed up by the Internet Archive as of March 11, 2007. Accessed August 29, 2017.

^ Raids by Housing Inspectors Anger Jersey Neighborhood, The New York Times, March 12, 1988.

^ "Students protest DevCo redevelopment", The Daily Targum, September 15, 1999.

^ Tenants' place is uncertain, The Daily Targum, November 9, 1999.

^ Urban Transit Hub Tax Credit Program Approved Projects, New Jersey Economic Development Authority. Accessed January 11, 2015.

^ Middlesex County: New Brunswick - Urban Transit Hub Tax Credits, New Jersey Economic Development Authority. Accessed January 11, 2015.

^ Martin, Antoinette. "In New Brunswick, a Mixed-Use Project Is Bustling", The New York Times, February 11, 2011. Accessed August 18, 2013. "The 624,000-square-foot building will have a public parking structure at the core of its first 10 stories; that core is to be wrapped in commercial and office space. A glass residential tower 14 stories tall will sit atop the parking structure ... As for the residences — 10 floors of rentals and 4 levels of penthouse condos — they are scheduled to be complete by April 2012."

^ Areas touching New Brunswick, MapIt. Accessed January 11, 2015.

^ ab Kratovil, Charlie. "New Brunswick 101: Your Source For Facts About The Hub City; A Comprehensive List of Every Neighborhood, Apartment Building, or Other Development in Hub City", New Brunswick Today, June 15, 2015. Accessed July 13, 2016. "Though New Brunswick does not use a system of neighborhood-based elections (and whether or not it should has been a contentious issue for more than a century), the city is still divided into five political subdivisions known as wards. There is no Third Ward, as most of that area was destroyed and redeveloped into a hotel and corporate headquarters in the 1980's."

^ Braunstein, Amy. "A Battle for Wards in New Jersey's Hub City", Shelterforce, October 17, 2010. Accessed July 13, 2016.

^ Keller, Karen. "New Brunswick vote to divide city into wards failed by narrow margin", The Star-Ledger, November 7, 2009. Accessed July 13, 2016. "A ballot initiative to divide New Brunswick into wards for city council elections has failed by a narrow margin, unofficial results show, with 50.8% voters against and 49.2% in favor."

^ "Feaster Park New Brunswick, NJ Neighborhood Profile - NeighborhoodScout". www.neighborhoodscout.com. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

^

"NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

^ "Station Name: NJ NEW BRUNSWICK 3 SE". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

^ Census Estimates for New Jersey April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 16, 2017.

^ Compendium of censuses 1726–1905: together with the tabulated returns of 1905, New Jersey Department of State, 1906. Accessed August 18, 2013.

^ Lundy, F. L., et al. Manual of the Legislature of New Jersey, Volume 116, p. 417. J.A. Fitzgerald, 1892. Accessed November 25, 2012.

^ Raum, John O. The History of New Jersey: From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, Volume 1, p. 246, J. E. Potter and company, 1877. Accessed August 18, 2013. "New Brunswick is divided into six wards. Its population in 1850 was 10,008; in 1860, 11,156; and in 1870, 15,058. It was incorporated as a city in 1784. Rutgers College built of a dark red freestone and finished in 1811 is located here." Census 1850 lists total population of 10,019.

^ Debow, James Dunwoody Brownson. The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850, p. 137. R. Armstrong, 1853. Accessed August 18, 2013.

^ Staff. A compendium of the ninth census, 1870, p. 260. United States Census Bureau, 1872. Accessed November 25, 2012.

^ Porter, Robert Percival. Preliminary Results as Contained in the Eleventh Census Bulletins: Volume III - 51 to 75, p. 98. United States Census Bureau, 1890. Accessed November 25, 2012.

^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, 1910, 1900, 1890, United States Census Bureau, p. 337. Accessed May 19, 2012.

^ Fifteenth Census of the United States : 1930 - Population Volume I, United States Census Bureau, p. 711. Accessed May 19, 2012.

^ Table 6. New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1930 - 1990 Archived 2015-05-10 at the Wayback Machine., New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed August 9, 2016.

^ abcde Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for New Brunswick city, New Jersey Archived 2012-01-17 at the Wayback Machine., United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 23, 2012.

^ abcde DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for New Brunswick city, Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 23, 2012.

^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006–2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for New Brunswick city, Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 19, 2012.

^ Dore Carroll, "New Brunswick: Medical field at hub of this transformation", The Star-Ledger, August 29, 2004.

^ Health Care Archived 2006-11-09 at the Wayback Machine., City of New Brunswick website.

^ "When High School is Much More", New York Times, 21 January 2001. Accessed 25 February 2016.

^ Urban Enterprise Zone Program, State of New Jersey. Accessed January 8, 2018.

^ New Jersey Urban Enterprise Zone Locations, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, locations as of January 1, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

^ "NJ Division of Taxation Reminds Consumers & Business Owners That Sales Tax Rate Will Change to 6.625% in the New Year", New Jersey Department of Treasury, press release dated December 27, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018. "The New Jersey Division of Taxation is reminding business owners that the State Sales and Use Tax rate will be reduced to 6.625% on Jan. 1, 2018. ... Rates for State Sales Tax in Urban Enterprise Zones also will change on Jan. 1, 2018. The rate in a designated UEZ will be 50 percent of the Sales Tax rate, or 3.3125 percent. The previous UEZ rate was 3.4375 percent."

^ Urban Enterprise Zones Effective and Expiration Dates, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed January 8, 2018.

^ Urban Enterprise Zone, City of New Brunswick. Accessed January 27, 2018.

^ History Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine., Crossroads Theatre Company. Accessed January 11, 2015.

^ About the Museum, Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. Accessed August 29, 2017. "Founded in 1966 as the Rutgers University Art Gallery, the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum was established in 1983 in response to the growth of the permanent collection."

^ About Us, Rutgers University Geology Museum. Accessed August 29, 2017. "The Rutgers Geology Museum, one of the oldest collegiate geology collections in the United States, was founded by state geologist and Rutgers professor George Hammell Cook in 1872."

^ Vostell – I disastri della pace/The Disasters of Peace. Varlerio Dehò, Edizioni Charta, Milano 1999,

ISBN 88-8158-253-8.

^ Net, Media Art (27 September 2018). "Media Art Net - Vostell, Wolf: TV Burying". www.medienkunstnetz.de. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

^ Shabe, John. "Who needs Internet pizza when Rutgers has The Grease Trucks?", The Star-Ledger, December 29, 2008. Accessed October 26, 2011.

^ Jovanovic, Rob. Perfect Sound Forever: The Story of Pavement, Justin, Charles & Co. 2004.

ISBN 9781932112078. Accessed August 29, 2017.

^ Jordan, Chris. "Court Tavern closing marks end of era in New Brunswick", Courier News, February 6, 2012. Accessed March 10, 2013.

^ Chaux, Giancarlo. "New Brunswick business owner plans to reopen the court tavern", The Daily Targum, April 17, 2012. Accessed January 11, 2015.

^ Kalet, Hank. "The List: 10 Best Places to See Indie Bands in the Garden State", NJ Spotlight, July 21, 2014. Accessed January 11, 2015.

^ "A sweaty New Brunswick basement just hosted the best N.J. concert of 2017 (PHOTOS)". Retrieved 27 September 2018.

^ City Council, City of New Brunswick. Accessed January 23, 2018.

^ 2017 Municipal Data Sheet, City of New Brunswick. Accessed January 23, 2018.

^ City of New Brunswick, Middlesex County, New Jersey. Accessed January 23, 2018.

^ November 8, 2016 General Election Results, Middlesex County, New Jersey. Accessed January 30, 2017.

^ November 4, 2014 General Election Results, Middlesex County, New Jersey. Accessed January 23, 2018.

^ via Associated press. "Police Slaying of a Black Man Brings Protest", The New York Times, July 2, 1991. Accessed May 19, 2012.

^ Lawyers See 'Pattern' of Police Brutality and Legal Abuse in New Brunswick Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine., Empower Our Neighborhoods

^ New Brunswick man charged in 20-year-old murder case, NJ.com