Hexamethylenetetramine

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

IUPAC name 1,3,5,7-Tetraazatricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane | |||

| Other names Hexamine; Methenamine; Urotropine; 1,3,5,7- tetraazaadamantane, Formin, Aminoform | |||

| Identifiers | |||

CAS Number |

| ||

3D model (JSmol) |

| ||

ChEBI |

| ||

ChEMBL |

| ||

ChemSpider |

| ||

ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.642 | ||

EC Number | 202-905-8 | ||

E number | E239 (preservatives) | ||

KEGG |

| ||

MeSH | Methenamine | ||

PubChem CID |

| ||

UNII |

| ||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

Chemical formula | C6H12N4 | ||

Molar mass | 140.186 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | White crystalline solid | ||

Density | 1.33 g/cm3 (at 20 °C) | ||

Melting point | 280 °C (536 °F; 553 K) (sublimes) | ||

Solubility in water | 85.3 g/100 mL | ||

Acidity (pKa) | 4.89[1] | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

ATC code | J01XX05 (WHO) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Highly combustible, harmful | ||

Flash point | 250 °C (482 °F; 523 K) | ||

Autoignition temperature | 410 °C (770 °F; 683 K) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

Infobox references | |||

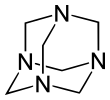

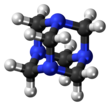

Hexamethylenetetramine or methenamine, also known as urotropin, is a heterocyclic organic compound with the formula (CH2)6N4. This white crystalline compound is highly soluble in water and polar organic solvents. It has a cage-like structure similar to adamantane. It is useful in the synthesis of other chemical compounds, e.g., plastics, pharmaceuticals, rubber additives. It sublimes in vacuum at 280 °C.

Contents

1 Synthesis, structure, reactivity

2 Applications

2.1 Medical uses

2.2 Histological stains

2.3 Solid fuel

2.4 Food additive

2.5 Reagent in organic chemistry

2.6 Explosives

3 Historical uses

4 Producers

5 References

Synthesis, structure, reactivity

Hexamethylenetetramine was discovered by Aleksandr Butlerov in 1859.[2][3]

It is prepared industrially by combining formaldehyde and ammonia.[4] The reaction can be conducted in gas phase and in solution.

The molecule has a symmetric tetrahedral cage-like structure, similar to adamantane, whose four "corners" are nitrogen atoms and "edges" are methylene bridges. Although the molecular shape defines a cage, no void space is available at the interior for binding other atoms or molecules, unlike crown ethers or larger cryptand structures.

The molecule behaves like an amine base, undergoing protonation and N-alkylation (e.g. Quaternium-15).

Applications

The dominant use of hexamethylenetetramine is in the production of powdery or liquid preparations of phenolic resins and phenolic resin moulding compounds, where it is added as a hardening component. These products are used as binders, e.g. in brake and clutch linings, abrasive products, non-woven textiles, formed parts produced by moulding processes, and fireproof materials.[4]

It has been proposed that hexamethylenetetramine could work as a molecular building block for self-assembled molecular crystals.[5][6]

Medical uses

As the mandelic acid salt (generic methenamine mandelate, USP[7]) it is used for the treatment of urinary tract infection. It decomposes at an acidic pH to form formaldehyde and ammonia, and the formaldehyde is bactericidal; the mandelic acid adds to this effect. Urinary acidity is typically ensured by co-administering vitamin C (ascorbic acid) or ammonium chloride. Its use had temporarily been reduced in the late 1990s, due to adverse effects, particularly chemically-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in overdose,[8] but its use has now been re-approved because of the prevalence of antibiotic resistance to more commonly used drugs. This drug is particularly suitable for long-term prophylactic treatment of urinary tract infection, because bacteria do not develop resistance to formaldehyde. It should not be used in the presence of renal insufficiency.

Methenamine in the form of cream and spray is successfully used for treatment of excessive sweating and concomitant odor.[medical citation needed]

Histological stains

Methenamine silver stains are used for staining in histology, including the following types:

Grocott's methenamine silver stain, used widely as a screen for fungal organisms.

Jones' stain, a methenamine silver-Periodic acid-Schiff that stains for basement membrane, availing to view the "spiked" Glomerular basement membrane associated with membranous glomerulonephritis.

Solid fuel

Together with 1,3,5-trioxane, hexamethylenetetramine is a component of hexamine fuel tablets used by campers, hobbyists, the military and relief organizations for heating camping food or military rations. It burns smokelessly, has a high energy density of 30.0 megajoules per kilogram (MJ/kg), does not liquify while burning, and leaves no ashes, although its fumes are toxic.

Standardized 0.149 g tablets of methenamine (hexamine) are used by fire-protection laboratories as a clean and reproducible fire source to test the flammability of carpets and rugs.[9]

Food additive

Hexamethylene tetramine or hexamine is also used as a food additive as a preservative (INS number 239). It is approved for usage for this purpose in the EU,[10] where it is listed under E number E239, however it is not approved in the USA, Russia, Australia, or New Zealand.[11]

Reagent in organic chemistry

Hexamethylenetetramine is a versatile reagent in organic synthesis.[12] It is used in the Duff reaction (formylation of arenes),[13] the Sommelet reaction (converting benzyl halides to aldehydes),[14] and in the Delepine reaction (synthesis of amines from alkyl halides).[15]

Explosives

Hexamethylenetetramine is the base component to produce RDX and, consequently, C-4[4] as well as Octogen, hexamine dinitrate and HMTD.

Historical uses

Hexamethylenetetramine was first introduced into the medical setting in 1899 as a urinary antiseptic.[16] However, it was only used in cases of acidic urine, whereas boric acid was used to treat urinary tract infections with alkaline urine.[17] Scientist De Eds found that there was a direct correlation between the acidity of hexamethylenetetramine's environment and the rate of its decomposition.[16] Therefore, its effectiveness as a drug depended greatly on the acidity of the urine rather than the amount of the drug administered.[17] In an alkaline environment, hexamethylenetetramine was found to be almost completely inactive.[17]

Hexamethylenetetramine was also used as a method of treatment for soldiers exposed to phosgene in World War I. Subsequent studies have shown that large doses of hexamethylenetetramine provide some protection if taken before phosgene exposure but none if taken afterwards.[18]

Producers

Since 1990 the number of European producers has been declining. The French SNPE factory closed in 1990; in 1993, the production of hexamethylenetetramine in Leuna, Germany ceased; in 1996, the Italian facility of Agrolinz closed down; in 2001, the UK producer Borden closed; in 2006, production at Chemko, Slovak Republic, was closed. Remaining producers include INEOS in Germany, Caldic in the Netherlands, and Hexion in Italy. In the US, Eli Lilly and Company stopped producing methenamine tablets in 2002.[9] In Australia, Hexamine Tablets for fuel are made by Thales Australia Ltd. In México, Hexamine is produced by Abiya.

References

^ Cooney, A. P.; Crampton, M. R.; Golding, P. (1986). "The acid-base behaviour of hexamine and its N-acetyl derivatives". J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 (6): 835. doi:10.1039/P29860000835..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Butlerow, A. (1859). "Ueber einige Derivate des Jodmethylens" [On some derivatives of methylene iodide]. Ann. Chem. Pharm. (in German). 111 (2): 242–252. doi:10.1002/jlac.18591110219. In this paper, Butlerov discovered formaldehyde, which he called "Dioxymethylen" (methylene dioxide) [page 247] because his empirical formula for it was incorrect (C4H4O4). On pages 249–250, he describes treating formaldehyde with ammonia gas, creating hexamine.

^ Butlerow, A. (1860). "Ueber ein neues Methylenderivat" [On a new methylene derivative]. Ann. Chem. Pharm. (in German). 115 (3): 322–327. doi:10.1002/jlac.18601150325.

^ abc Eller, K.; Henkes, E.; Rossbacher, R.; Höke, H. (2000). "Amines, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_001. ISBN 9783527306732.

^ Markle, R. C. (2000). "Molecular building blocks and development strategies for molecular nanotechnology". Nanotechnology. 11: 89. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/11/2/309.

^ Garcia, J. C.; Justo, J. F.; Machado, W. V. M.; Assali, L. V. C. (2009). "Functionalized adamantane: building blocks for nanostructure self-assembly". Phys. Rev. B. 80: 125421. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.125421.

^ "Methenamine mandelate, USP". Edenbridge Pharmaceuticals.

^ Ross, R. R.; Conway, G. F. (1970). "Hemorrhagic cystitis following accidental overdose of methenamine mandelate". Am. J. Dis. Child. 119 (1): 86–87. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1970.02100050088021. PMID 5410299.

^ ab Alan H. Schoen (2004), Re: Equialence of methenamine Tablets Standard for Flammability of Carpets and Rugs Archived 2008-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Consumer product Safety Commission, Washington, DC, July 29, 2004. Many other countries who still produce this include Russia, Saudi Arabia, China and Australia.

^ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

^ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 - Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

^ Blažzević, N.; Kolbah, D.; Belin, B.; Šunjić, V.; Kajfež, F. (1979). "Hexamethylenetetramine, A Versatile Reagent in Organic Synthesis". Synthesis. 1979 (3): 161–176. doi:10.1055/s-1979-28602.

^ Allen, C. F. H.; Leubne, G. W. (1951). "Syringic Aldehyde". Organic Syntheses. 31: 92. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.031.0092.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Wiberg, K. B. (1963). "2-Thiophenaldehyde". Organic Syntheses. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.000.0000.; Collective Volume, 3, p. 811

^ Bottini, A. T.; Dev, V.; Klinck, J. (1963). "2-Bromoallylamine". Organic Syntheses. 43: 6. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.043.0006.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ ab Heathcote, Reginald St. A. (1935). "HEXAMINE AS AN URINARY ANTISEPTIC: I. ITS RATE OF HYDROLYSIS AT DIFFERENT HYDROGEN ION CONCENTRATIONS. II. ITS ANTISEPTIC POWER AGAINST VARIOUS BACTERIA IN URINE". British Journal of Urology. 7 (1): 9–32. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1935.tb11265.x. ISSN 0007-1331.

^ abc Elliot (1913). "On Urinary Antiseptics". British Medical Journal. 98: 685–686.

^ Diller, Werner F. (1980). "The methenamine misunderstanding in the therapy of phosgene poisoning (review article)". Archives of Toxicology. 46 (3–4): 199–206. doi:10.1007/BF00310435. ISSN 0340-5761.