Chemical weapon

Pallets of 155 mm artillery shells containing "HD" (distilled sulfur mustard agent) at Pueblo Depot Activity (PUDA) chemical weapons storage facility | |

| Blister agents | |

|---|---|

| Phosgene oxime | (CX) |

| Lewisite | (L) |

Sulfur mustard (Yperite) | (HD) |

| Nitrogen mustard | (HN) |

| Nerve agents | |

| Tabun | (GA) |

| Sarin | (GB) |

| Soman | (GD) |

| Cyclosarin | (GF) |

| VX | (VX) |

| Blood agents | |

| Cyanogen chloride | (CK) |

| Hydrogen cyanide | (AC) |

| Choking agents | |

| Chloropicrin | (PS) |

| Phosgene | (CG) |

| Diphosgene | (DP) |

| Chlorine | (CI) |

| |

| Soviet chemical weapons canister from an Albanian stockpile[1] | |

| Part of a series on | |||||

| Chemical agents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lethal agents | |||||

Blood

| |||||

Blister

| |||||

Nerve

| |||||

Nettle

| |||||

Pulmonary/choking

| |||||

Vomiting

| |||||

Incapacitating agents | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Weapons of mass destruction |

|---|

|

By type |

|

By country |

|

Proliferation |

|

Treaties |

|

|

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), "the term chemical weapon may also be applied to any toxic chemical or its precursor that can cause death, injury, temporary incapacitation or sensory irritation through its chemical action. Munitions or other delivery devices designed to deliver chemical weapons, whether filled or unfilled, are also considered weapons themselves."[2]

Chemical weapons are classified as weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), though they are distinct from nuclear weapons, biological weapons, and radiological weapons. All may be used in warfare and are known by the military acronym NBC (for nuclear, biological, and chemical warfare). Weapons of mass destruction are distinct from conventional weapons, which are primarily effective due to their explosive, kinetic, or incendiary potential. Chemical weapons can be widely dispersed in gas, liquid and solid forms, and may easily afflict others than the intended targets. Nerve gas, tear gas and pepper spray are three modern examples of chemical weapons.

Lethal unitary chemical agents and munitions are extremely volatile and they constitute a class of hazardous chemical weapons that have been stockpiled by many nations. Unitary agents are effective on their own and do not require mixing with other agents. The most dangerous of these are nerve agents (GA, GB, GD, and VX) and vesicant (blister) agents, which include formulations of sulfur mustard such as H, HT, and HD. They all are liquids at normal room temperature, but become gaseous when released. Widely used during the First World War, the effects of so-called mustard gas, phosgene gas and others caused lung searing, blindness, death and maiming.

The Nazi Germans during WW-II committed genocide mainly against Jews but included other targeted populations in the Holocaust, a commercial hydrogen cyanide blood agent trade named Zyklon B discharged in large gas chambers was the preferred method to efficiently murder their victims in a continuing industrial fashion[3], this resulted in the largest death toll to chemical weapons in history.[4]

As of 2016[update], CS gas and pepper spray remain in common use for policing and riot control; while CS is considered a non-lethal weapon, pepper spray is known for its lethal potential. Under the Chemical Weapons Convention (1993), there is a legally binding, worldwide ban on the production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons and their precursors. Notwithstanding, large stockpiles of chemical weapons continue to exist, usually justified as a precaution against putative use by an aggressor.

Contents

1 International law on chemical weapons

1.1 Before the Second World War

1.2 Modern agreements

2 Use

3 Countries with stockpiles

3.1 CWC states with declared stockpiles

3.1.1 India

3.1.2 Iraq

3.1.3 Japan

3.1.4 Libya

3.1.5 Russia

3.1.6 Syria

3.1.7 United States

3.2 Non-CWC states with stockpiles

3.2.1 Israel

3.2.2 North Korea

4 Manner and form

5 Disposal

6 Lethality

7 Exposure during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn

8 Unitary versus binary weapons

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

International law on chemical weapons

Before the Second World War

International law has prohibited the use of chemical weapons since 1899, under the Hague Convention: Article 23 of the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land adopted by the First Hague Conference "especially" prohibited employing "poison and poisoned arms".[5][6] A separate declaration stated that in any war between signatory powers, the parties would abstain from using projectiles "the object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases".[7]

The Washington Naval Treaty, signed February 6, 1922, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, aimed at banning CW but did not succeed because France rejected it. The subsequent failure to include CW has contributed to the resultant increase in stockpiles.[8]

The Geneva Protocol, officially known as the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, is an International treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons. It was signed at Geneva June 17, 1925, and entered into force on February 8, 1928. 133 nations are listed as state parties[9] to the treaty. Ukraine is the newest signatory; acceding August 7, 2003.[10]

This treaty states that chemical and biological weapons are "justly condemned by the general opinion of the civilised world". And while the treaty prohibits the use of chemical and biological weapons, it does not address the production, storage, or transfer of these weapons. Treaties that followed the Geneva Protocol did address those omissions and have been enacted.

Modern agreements

The 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) is the most recent arms control agreement with the force of International law. Its full name is the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction. That agreement outlaws the production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons. It is administered by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which is an independent organization based in The Hague.[11]

The OPCW administers the terms of the CWC to 192 signatories, which represents 98% of the global population. As of June 2016[update], 66,368 of 72,525 metric tonnes, (92% of CW stockpiles), have been verified as destroyed.[12][13] The OPCW has conducted 6,327 inspections at 235 chemical weapon-related sites and 2,255 industrial sites. These inspections have affected the sovereign territory of 86 States Parties since April 1997. Worldwide, 4,732 industrial facilities are subject to inspection under provisions of the CWC.[13]

Use

Chemical warfare (CW) involves using the toxic properties of chemical substances as weapons. This type of warfare is distinct from nuclear warfare and biological warfare, which together make up NBC, the military initialism for Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical (warfare or weapons). None of these fall under the term conventional weapons, which are primarily effective because of their destructive potential. Chemical warfare does not depend upon explosive force to achieve an objective. It depends upon the unique properties of the chemical agent weaponized.

A British gas bomb that was used during World War I.

A lethal agent is designed to injure, incapacitate, or kill an opposing force, or deny unhindered use of a particular area of terrain. Defoliants are used to quickly kill vegetation and deny its use for cover and concealment. CW can also be used against agriculture and livestock to promote hunger and starvation. Chemical payloads can be delivered by remote controlled container release, aircraft, or rocket. Protection against chemical weapons includes proper equipment, training, and decontamination measures.

Countries with stockpiles

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Chemical weapon proliferation. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2018. |

CWC states with declared stockpiles

Of 190 signatory nations to the CWC, state parties listed below have also declared stockpiles, agreed to monitored disposal, and verification, and in some cases, used CW in conflict. Both military targets and civilian populations have been affected; affected populations were not always damaged collaterally; instead, at times: themselves the target of the attack. As of 2017[update], only North Korea and the United States are confirmed to have remaining stockpiles of CW.

India

India declared its stock of chemical weapons in June 1997. India's declaration came after the entry into force of the CWC that created the OPCW. India declared a stockpile of 1044 tonnes of sulfur mustard in its possession.[14][15] On January 14, 1993, India became an original signatory to the CWC. In 2005, among the six nations that declared stockpiles of chemical weapons, India was the only one to meet its deadline for chemical weapons destruction and for inspection of its facilities by the OPCW. By the end of 2006, India had destroyed more than 75 percent of its chemical weapons/material stockpile and was granted an extension for destroying the remaining CW until April 2009. It was anticipated that India would achieve 100 percent destruction within that time frame.[15] On May 14, 2009, India informed the United Nations that it had completely destroyed its stockpile of chemical weapons.[16]

Iraq

An Iranian soldier wearing a gas mask during the Iran–Iraq War. Iraq massively used chemical weapons during Iran–Iraq War.

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which oversees destruction measures, has announced "The government of Iraq has deposited its instrument of accession to the Chemical Weapons Convention with the Secretary General of the United Nations and within 30 days, on 12 February 2009, will become the 186th State Party to the Convention".[17][18] Iraq has also declared stockpiles of CW, and because of their recent accession is the only State Party exempted from the destruction time-line.[19] On September 7, 2011, Hoshyar Zebari entered the OPCW headquarters, becoming the first Iraqi Foreign Minister to officially visit since the country joined the CWC.[20]

Iraq used mustard gas in an attack against Kurdish people on March 16, 1988, Halabja chemical attack.The attack killed between 3,200 and 5,000 people and injured 7,000 to 10,000 more, most of them civilians. On June 28, 1987 in Sardasht, on two separate attacks against four residential areas, victims were estimated as 10 civilians dead and 650 civilians injured.[21] Iraq massively used chemical weapons during Iran–Iraq War, and so far, Kurdish people are the biggest victims of chemical weapons.

Japan

Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces wearing gas masks and rubber gloves during a chemical attack near Chapei in the Battle of Shanghai.[22]

Japan stored chemical weapons on the territory of mainland China between 1937 and 1945. The weapons mostly contained a mustard gas-lewisite mixture.[23] They are classified as abandoned chemical weapons under the CWC; their destruction under a joint Japan-China program started in September 2010, in Nanjing using mobile destruction facilities.[24]

Libya

Libya used chemical weapons, under Muammar Gaddafi's regime, in a war with Chad. In 2003, Gaddafi agreed to accede to the CWC in exchange for "rapprochement" with western nations. At the time of the Libyan uprising against Gaddafi, Libya still controlled approximately 11.25 tons of poisonous mustard gas. Because of destabilization, concerns increased regarding possibilities and likelihood that control of these agents could be lost. With terrorism at the core of concern,[25] international bodies cooperated to ensure Libya is held to its obligations under the treaty.[26] Libya's post-Gaddafi National Transitional Council is cooperating with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons regarding the destruction of all legacy chemical weapons in the country.[27] After assessing the chemical stockpiles, the Libyan government will receive a deadline from the OPCW to destroy the CW.[28]

Russia

Chemical weapons formerly stored in Russia.

Former Russian CW stockpiles.

Russia entered the CWC with the largest declared stockpile of chemical weapons.[29] By 2010 the country had destroyed 18,241 tonnes at destruction facilities located in Gorny (Saratov Oblast) and Kambarka (Udmurt Republic), where operations have finished, and Shchuchye (Kurgan Oblast), Maradykovsky (Kirov Oblast), Leonidovka (Penza Oblast) while installations are under construction in Pochep (Bryansk Oblast) and Kizner (Udmurt Republic).[30] By 2016, Russia destroyed around 94% of its chemical weapons, planning to completely destroy its remaining stockpile by the end of 2018.[31] On September 27, 2017 Russia announced the destruction of the last batch of chemical weapons, completing the total destruction of its chemical arsenal, ahead of schedule.[32]

On March 4, 2018, Russia was alleged to have conducted a chemical attack in Salisbury, UK that left 5 injured including the alleged target of the attack, Sergei Skripal.[33]

Syria

Prior to September 2013, Syria was one of the 7 states that were not party to the Chemical Weapons Convention. It is, however, party to the 1925 Geneva Protocol and therefore, prohibited from using chemical weapons in war yet unhindered from the production, storage or transfer of CW.

When questioned about the topic, Syrian officials stated that they feel it is an appropriate deterrent against Israel's undeclared nuclear weapons program which they believe exists. On July 23, 2012, the Syrian government acknowledged, for the first time, that it had chemical weapons.[34]

Independent assessments indicate that Syria could have produced up to a few hundred tons of chemical agent per year. Syria reportedly manufactures the unitary agents: Sarin, Tabun, VX, and mustard gas.[35]

Syrian chemical weapons production facilities have been identified by Western nonproliferation experts at the following 5 sites, plus a suspected weapons base:[36]

A Syrian soldier aims an AK-47 assault rifle wearing a Soviet-made, model ShMS nuclear–biological–chemical warfare mask.

- Al Safir (Scud missile base)

- Cerin

- Hama

- Homs

- Latakia

- Palmyra

In July 2007, a Syrian arms depot exploded, killing at least 15 Syrians. Jane's Defence Weekly, a UK magazine reporting on military and corporate affairs, believed that the explosion happened when Iranian and Syrian military personnel attempted to fit a Scud missile with a mustard gas warhead. Syria stated that the blast was accidental and not chemical related.[37]

On July 13, 2012, the Syrian government moved its stockpile to an undisclosed location.[38]

In September 2012, information emerged that the Syrian military had begun testing chemical weapons, and was reinforcing and resupplying a base housing these weapons located east of Aleppo in August.[39][40]

On March 19, 2013, news emerged from Syria indicating the first use of chemical weapons since the beginning of the Syrian uprising.[41]

On August 21, 2013, testimony and photographic evidence emerged from Syria indicating a large-scale chemical weapons attack on Ghouta, a populated urban center.[42]

An agreement was reached September 14, 2013, called the Framework For Elimination of Syrian Chemical Weapons, leading to the elimination of Syria's chemical weapon stockpiles by mid-2014.[43][44]

On October 14, 2013, Syria officially acceded to the Chemical Weapons Convention but there were multiple cases of chemical weapon use in Syria afterwards.

United States

The United States has destroyed about 90% of the chemical weapons stockpile it declared in 1997, guided by RCRA regulations[45]. As of 2012 complete destruction was not expected until 2023.[46]

The U.S. policy on the use of chemical weapons is to reserve the right to retaliate. First use, or preemptive use, is a violation of stated policy. Only the president of the United States can authorize the first retaliatory use.[47] Official policy now reflects the likelihood of chemical weapons being used as a terrorist weapon.[48][49]

Non-CWC states with stockpiles

Israel

Although Israel has signed the CWC, it has not ratified the treaty and therefore is not officially bound by its tenets.[11] The country is believed to have a significant stockpile of chemical weapons, likely the most abundant in the Middle-East, according to the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service.[50] A 1983 CIA report stated that Israel, after "finding itself surrounded by front-line Arab states with budding CW capabilities, became increasingly conscious of its vulnerability to chemical attack ... undertook a program of chemical warfare preparations in both offensive and protective areas ... In late 1982, a probable CW nerve agent production facility and a storage facility were identified at the Dimona Sensitive Storage Area in the Negev Desert. Other CW agent production is believed to exist within a well-developed Israeli chemical industry."[51]

In 1992, El Al Flight 1862 crashed on its way to Tel Aviv and was found to be carrying 190 liters of dimethyl methylphosphonate, a CWC schedule 2 chemical used in the synthesis of sarin nerve gas. Israel insisted at the time that the materials were non-toxic. This shipment was coming from a US chemical plant to the IIBR under a US Department of Commerce license.[52]

In 1993, the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment WMD proliferation assessment recorded Israel as a country generally reported as having undeclared offensive chemical warfare capabilities.[53] However, it is unclear whether Israel still keeps its alleged stockpile of chemical weapons.[50]

North Korea

North Korea is not a signatory of the CWC and has never officially acknowledged the existence of its CW program. Nevertheless, the country is believed to possess a substantial arsenal of chemical weapons. It reportedly acquired the technology necessary to produce tabun and mustard gas as early as the 1950s.[54] In 2009, the International Crisis Group reported that the consensus expert view was that North Korea had a stockpile of about 2,500 to 5,000 tonnes of chemical weapons, including mustard gas, sarin (GB) and other nerve agents including VX.[55]

Manner and form

Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System prior to demolition.

A Swedish Army soldier wearing a chemical agent protective suit (C-vätskeskydd) and protection mask (skyddsmask 90).

There are three basic configurations in which these agents are stored. The first are self-contained munitions like projectiles, cartridges, mines, and rockets; these can contain propellant and/or explosive components. The next form are aircraft-delivered munitions. This form never has an explosive component.[56] Together they comprise the two forms that have been weaponized and are ready for their intended use. The U.S. stockpile consisted of 39% of these weapon ready munitions. The final of the three forms are raw agent housed in one-ton containers. The remaining 61%[56] of the stockpile was in this form.[57] Whereas these chemicals exist in liquid form at normal room temperature,[56][58] the sulfur mustards H, and HD freeze in temperatures below 55 °F (12.8 °C). Mixing lewisite with distilled mustard lowers the freezing point to −13 °F (−25.0 °C).[47]

Higher temperatures are a bigger concern because the possibility of an explosion increases as the temperatures rise. A fire at one of these facilities would endanger the surrounding community as well as the personnel at the installations.[59] Perhaps more so for the community having much less access to protective equipment and specialized training.[60] The Oak Ridge National Laboratory conducted a study to assess capabilities and costs for protecting civilian populations during related emergencies,[61] and the effectiveness of expedient, in-place shelters.[62]

Disposal

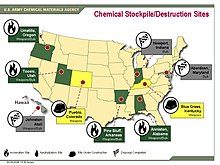

Stockpile/disposal site locations for the United States' chemical weapons and the sites operating status as of August 28, 2008.

The stockpiles, which have been maintained for more than 50 years,[8] are now considered obsolete.[63]Public Law 99-145, contains section 1412, which directs the Department of Defense (DOD) to dispose of the stockpiles. This directive fell upon the DOD with joint cooperation from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).[56] The Congressional directive has resulted in the present Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program.

Historically, chemical munitions have been disposed of by land burial, open burning, and ocean dumping (referred to as Operation CHASE).[64] However, in 1969, the National Research Council (NRC) recommended that ocean dumping be discontinued. The Army then began a study of disposal technologies, including the assessment of incineration as well as chemical neutralization methods. In 1982, that study culminated in the selection of incineration technology, which is now incorporated into what is known as the baseline system. Construction of the Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) began in 1985.

This was to be a full-scale prototype facility using the baseline system. The prototype was a success but there were still many concerns about CONUS operations. To address growing public concern over incineration, Congress, in 1992, directed the Army to evaluate alternative disposal approaches that might be "significantly safer", more cost effective, and which could be completed within the established time frame. The Army was directed to report to Congress on potential alternative technologies by the end of 1993, and to include in that report: "any recommendations that the National Academy of Sciences makes ..."[57] In June 2007, the disposal program achieved the milestone of reaching 45% destruction of the chemical weapon stockpile.[65] The Chemical Materials Agency (CMA) releases regular updates to the public regarding the status of the disposal program.[66] By October 2010, the program had reached 80% destruction status.[67]

Lethality

Chemical weapons are said to "make deliberate use of the toxic properties of chemical substances to inflict death".[68] At the start of World War II it was widely reported in newspapers that "entire regions of Europe" would be turned into "lifeless wastelands".[69] However, chemical weapons were not used to the extent reported by a scaremongering press.

An unintended chemical weapon release occurred at the port of Bari. A German attack on the evening of December 2, 1943, damaged U.S. vessels in the harbour and the resultant release from their hulls of mustard gas inflicted a total of 628 casualties.[70][71][72]

An Australian observer who has moved into a gas-affected target area to record results, examines an un-exploded shell.

The U.S. Government was highly criticized for exposing American service members to chemical agents while testing the effects of exposure. These tests were often performed without the consent or prior knowledge of the soldiers affected.[73] Australian service personnel were also exposed as a result of the "Brook Island trials"[74] carried out by the British Government to determine the likely consequences of chemical warfare in tropical conditions; little was known of such possibilities at that time.

Some chemical agents are designed to produce mind-altering changes; rendering the victim unable to perform their assigned mission. These are classified as incapacitating agents, and lethality is not a factor of their effectiveness.[75]

Exposure during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn

During Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn, service members who demolished or handled older explosive ordnance may have been exposed to blister agents (mustard agent) or nerve agents (sarin).[76] According to The New York Times, "In all, American troops secretly reported finding roughly 5,000 chemical warheads, shells or aviation bombs, according to interviews with dozens of participants, Iraqi and American officials, and heavily redacted intelligence documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act."[77] Among these, over 2,400 nerve-agent rockets were found in summer 2006 at Camp Taji, a former Republican Guard compound. "These weapons were not part of an active arsenal"; "they were remnants from an Iraqi program in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq war".[77]

The Department of Defense (DOD) wants to identify those who experienced symptoms following exposure to chemical warfare agent. The likelihood of long-term effects from a single exposure is related to the severity of the exposure. The severity of exposure is estimated from the onset of signs and symptoms coupled with how long it took for them to develop. DOD is interested in their symptoms and their current status. DOD wants to be sure that the exposure is documented in their medical record, that the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is informed, and that they understand their future health risks. DOD can provide them with information regarding their exposure to share with their health care provider, and recommend follow-up if needed.

While DOD has identified some individuals, they are conducting medical record screenings on units, and reviewing Post Deployment Health Assessment and Reassessment forms to identify other exposed individuals. Because these methods have limitations, individuals are encouraged to self-identify by using the DOD Hotline: 800-497-6261.[citation needed]

Unitary versus binary weapons

Binary munitions contain two, unmixed and isolated chemicals that do not react to produce lethal effects until mixed. This usually happens just prior to battlefield use. In contrast, unitary weapons are lethal chemical munitions that produce a toxic result in their existing state.[78] The majority of the chemical weapon stockpile is unitary and most of it is stored in one-ton bulk containers.[79][80]

See also

- 1990 Chemical Weapons Accord

- CB military symbol

- General-purpose criterion

- List of chemical warfare agents

- Riot control

References

^ "Types of Chemical Weapons" (PDF). www.fas.org. Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved June 27, 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Brief Description of Chemical Weapons". Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

^ From Cooperation to Complicity: Degussa in the Third Reich, Peter Hayes, 2004, pp 2, 272,

ISBN 0-521-78227-9

^ Article 23. wikisource.org. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Laws of War: Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague II); Article 23". www.yale.edu. July 29, 1899. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ "Laws of War: Declaration on the Use of Projectiles the Object of Which is the Diffusion of Asphyxiating or Deleterious Gases". www.yale.edu. July 29, 1899. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ ab Shrivastav, Sanjeev Kumar (January 1, 2010). "United States of America: Chemical Weapons Profile". www.idsa.in. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ "Geneva Protocol reservations: Project on Chemical and Biological Warfare". www.sipri.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ "High Contracting Parties to the Geneva Protocol". www.sipri.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ ab "Status as at: 07-11-2010 01:48:46 EDT, Chapter XXVI, Disarmament". www.un.org. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ "Demilitarisation". www.opcw.org. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

^ ab "Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (home page)". www.opcw.org. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ Smithson, Amy Gaffney, Frank, Jr.; 700+ words. "India declares its stock of chemical weapons". Highbeam.com. Retrieved 2013-08-27.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ ab "India to destroy chemical weapons stockpile by 2009". Dominican Today. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

^ "Zee News - India destroys its chemical weapons stockpile". Zeenews.india.com. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

^ "Iraq Joins the Chemical Weapons Convention". The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

^ "Iraq Designates National Authority For The Chemical Weapons Convention". Opcw.org. Retrieved 2011-09-15.

^ Schneidmiller, Chris. "Iraq Joins Chemical Weapons Convention". Global Security Newswire. Retrieved 2011-09-15.

^ "Minister of Foreign Affairs of Iraq Visits the OPCW to Discuss Implementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention". www.opcw.org. September 8, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "Iran Profile — Chemical Chronology 1987". Nuclear Threat Initiative. October 2003. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-01.

^ "Chemical warfare". World War II. DesertWar.net.

^ "Abandoned Chemical Weapons (ACW) in China". NTI.org. June 2, 2004. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

^ "Ceremony Marks Start of Destruction of Chemical Weapons Abandoned by Japan in China". OPCW. September 8, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

^ "Chemical terrorism: prevention, response and the role of legislation" (PDF). www.vertic.org. Truth & Verify. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Gaddafi's chemical weapons spark renewed worries". www.washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. August 16, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

^ "Libya's NTC pledges to destroy chemical weapons: OPCW". www.spacewar.com. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

^ "Chemical weapons inspectors to return to Libya". Spacewar.com. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

^ "Converting Former Soviet Chemical Weapons Plants" (PDF). Jonathan B. Tucker.

^ "Russia Continues Chemical Weapons Disposal". www.nti.org. November 8, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "In Russia, eliminated about 95% of toxic substances - NewsRussia".

^ "Putin lauds elimination of last chemical agent from Russian stockpiles as 'historic event'". TASS. September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

^ "Russia-Skripal scandal: What we know so far". Al Jazeera. March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

^ "Syria threatens to use chemical arms if attacked". www.foxnews.com. July 23, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "Syria Chemical Weapons". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 27, 2016.According to a French intelligence report released 03 September 2013, the Syrian stockpile included:

^ "Special Weapons Facilities". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "HOW CLOSE WERE WE TO A THIRD WORLD WAR? What really happened when". www.bibliotecapleyades.net. The Sunday Herald. October 20, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Wary of rebels and chaos, Syria moves chemical weapons". www.chicagotribune.com. July 13, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "Syria Tested Chemical Weapons Systems, Witnesses Say". Der Spiegel. September 17, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

^ "Report: Syria tested chemical weapons delivery systems in August". Haaretz. September 17, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

^ "Syrians trade Khan al-Assal chemical weapons claims". BBC. March 19, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

^ "Syria chemical weapons allegations". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. October 31, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Framework for Elimination of Syrian Chemical Weapons". www.state.gov. September 14, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ Gordon, Michael R. (September 14, 2013). "U.S. and Russia Reach Deal to Destroy Syria's Chemical Arms". The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

^ Horinko, Marianne, Cathryn Courtin. “Waste Management: A Half Century of Progress.” EPA Alumni Association. March 2016.

^ Army Agency Completes Mission to Destroy Chemical Weapons Archived September 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, USCMA, January 21, 2012

^ ab "FM 3-9 (field manual)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-10.

^ Tucker, Jonathan B.; Walker, Paul F. (April 27, 2009). "Getting chemical weapons destruction back on track". www.thebulletin.org. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "Umatilla Chemical Depot (press release)". U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency. August 10, 2010.

^ ab "Israel stockpiled chemical weapons decades ago". www.rt.com. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "1NIE on Israeli Chemical Weapons". www.scribd.com. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "World: Europe Israel says El Al crash chemical 'non-toxic'". www.news.bbc.co.uk. BBC News. October 2, 1998. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction: Assessing the Risks" (PDF). www.princeton.edu. August 1, 1993. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "North Korean Military Capabilities". Retrieved October 5, 2006.

^ Jon Herskovitz (June 18, 2009). "North Korea chemical weapons threaten region: report". Reuters. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

^ abcd "Public Law 99-145 Attachment E" (PDF).

^ ab "Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Volume 3: Appendices A-S — Storming Media". Stormingmedia.us. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "Record Version Written Statement by Carmen J. Spencer Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army" (PDF). www.chsdemocrats.house.govhouse.gov. June 15, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ Rogers, G. O.; Watson, A. P.; Sorensen, J. H.; Sharp, R. D.; Carnes, S. A. (April 1, 1990). "EVALUATING PROTECTIVE ACTIONS FOR CHEMICAL AGENT EMERGENCIES" (PDF). www.emc.ed.ornl.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "Methods for Assessing and Reducing Injury from Chemical Accidents" (PDF). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

^ "Technical Options for Protecting Civilians from Toxic Vapors and Gases" (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

^ "Effectiveness of expedient sheltering in place in a residents" (PDF). Journal of Hazardous Materials, Elsiver.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ John Pike. "Chemical Weapons". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

^ John Pike. "Operation CHASE (for "Cut Holes and Sink 'Em")". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "45 Percent CWC Milestone". U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

^ "Agent Destruction Status". United States Army Chemical Materials Agency.

^ "CMA Reaches 80% Chemical Weapons Destruction Mark". Cma.army.mil. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

^ "TextHandbook-EforS.fm" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2007. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "[2.0] A History Of Chemical Warfare (2)". Vectorsite.net. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "Mustard Disaster at Bari". www.mcm.fhpr.osd.mil. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

^ "Naval Armed Guard: at Bari, Italy". History.navy.mil. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "Text of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention".

^ "IS MILITARY RESEARCH HAZARDOUS TO VETERANS' HEALTH? LESSONS SPANNING HALF A CENTURY. UNITED STATES SENATE, DECEMBER 8, 1994". Gulfweb.org. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "Brook Island Trials of Mustard Gas during WW2". Home.st.net.au. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

^ "007 Incapacitating Agents". Brooksidepress.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

^ "Chemical Warfare Agents". U.S. Army Public Health Command. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

^ ab C. J. Chivers. The Secret Casualties of Iraq’s Abandoned Chemical Weapons. The New York Times. October 14, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/14/world/middleeast/us-casualties-of-iraq-chemical-weapons.html?nlid=64847459&_r=0

^ Alternative technologies for the destruction of chemicam agents and munitions. National Research Council (U.S.). 1993. ISBN 9780309049467.

^ "Beyond the Chemical Weapons Stockpile: The Challenge of Non-Stockpile Materiel". Armscontrol.org. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

^ Institute of Medicine; Committee on the Survey of the Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite (1993). Veterans at Risk: The Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite. National Academies Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-309-04832-3.

Further reading

- Glenn Cross, Dirty War: Rhodesia and Chemical Biological Warfare, 1975–1980, Helion & Company, 2017

External links

Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Home page

Lecture by Santiago Oñate Laborde entitled The Chemical Weapons Convention: an Overview in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

"The Government of Canada ""Challenge"" for chemical substances that are a high priority for action".

"Chemical categories". Archived from the original on November 8, 2005.

"Chemical Warfare Agents".

"U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency (home page)". Archived from the original on October 15, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2010.