Sopoćani

Coordinates: 43°7′5″N 20°22′26″E / 43.11806°N 20.37389°E / 43.11806; 20.37389

Overview of the Sopoćani | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Сопоћани |

| Order | Serbian Orthodox |

| Established | 1259 - 1270 |

| Disestablished | 1689 |

| Reestablished | 1926 |

| Dedicated to | Holy Trinity |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | King Stefan Uroš I |

| Site | |

| Location | In Raška, Serbia, near the source of the Raška River in the region of Ras, the centre of the Serbian medieval state. |

| Public access | Yes |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Stari Ras and Sopoćani |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 96 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Sopoćani monastery (Serbian Cyrillic: Сопоћани) (pronounced [sǒpotɕani]), an endowment of King Stefan Uroš I of Serbia, was built from 1259 to 1270, near the source of the Raška River in the region of Ras, the centre of the Serbian medieval state. It is a designated World Heritage Site, added in 1979 with Stari Ras.

Contents

1 History

2 Art history and influence

2.1 Art reconstruction

3 Notable art and techniques

3.1 Paintings

3.2 Iconography

4 Gallery

5 Burials

6 In popular culture

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

History

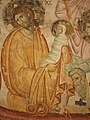

Detail of the fresco Dormition of the Mother of God from Sopoćani c. 1265 (See also:Palaiologian Renaissance)

In the 1160s, the Great Zupan Stefan Nemanja consolidated his power on the throne in Raska.[1] Although Nemanja's sons got the title of king and established the church as independent by making it autocephalous, developed the economic system and coined money, became richer and more sophisticated, the times, the work and person of Stefan Nemanja remained a great model and an example to be emulated by the younger generations. Sopoćani was an endowment of the Serbian King Stefan Uroš I, son to Stefan the First-Crowned and Nemanja's grandson. It was built in 1260 by King Uroš I Nemanjić as a church which would serve as his burial place, and was extended and renovated in the mid-14th century by his great-grandson Dušan. The church is dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Of the former larger monastery complex, which comprised numerous structures (dining rooms, residential buildings and others), today only the Church of the Holy Trinity remains. The monastery was once surrounded by a high stone wall with two gates. The completion of the painting of the main parts of the church can be indirectly dated to between 1263 and 1270. In Sopocani a decorative plan was carried out which was formed throughout the thirteenth century - in the chancel there are liturgical scenes, in the nave Christ's salvation work is shown through a cycle of the Great Feasts, in the narthex the Old Testament, dogmatic and eschatological themes are presented. Through the iconographic portraits of the Nemanjic family and through historical scenes Simeon Nemanja and Saint Sava. After Gradac (about 1275), the endowment of Queen Helen of Anjou, the wife of the founder of Sopocani - King Uros I - whose painters were high on the scale of creativity, there was a hiatus in creative artwork in Serbia.

Archbishop Sava II, who became the head of the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1263, is represented in the procession of archbishops in the area of the altar. The frescoes of Sopoćani are considered by some experts on Serbian medieval art as the most beautiful of that period. On the western wall of the nave is a famous fresco of the Dormition of the Virgin.

In the 16th century the monks had to temporarily leave the monastery on several occasions due to the Ottoman threat. Finally, during one of the raids in 1689 the Ottoman Turks set fire to the monastery and carried off the lead from the church roof. The brotherhood escaped with some important relics to Kosovo - but did not return to Sopoćani; it remained deserted for over two hundred years, until the 20th century. The church slowly decayed: its vaults caved in, its dome fell down, and the remains of the surrounding buildings were covered with rubble and earth.

Finally, during the 20th century the monastery was restored and today it is settled by a thriving brotherhood of dedicated monks. The fact that most of the Sopoćani frescoes still shine with radiant beauty - surviving more than two centuries of extreme exposure to the elements.

Sopoćani was declared Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance in 1979, and it is protected by Republic of Serbia.

Art history and influence

The art in Sopoćani was implemented periodically through the years following its completion in 1260. The subjects of the art include Christian Saints, national saints, as well as episcopal and illuminative narratives of Christianity. These narratives follow a left-to-right order of narration, needing to be viewed in a specific order to be understood.[2] The classical art style of the church is largely influenced by late Byzantine art, such as that of the Basilica of San Vitale and other Byzantine churches.[3] Some of the frescoes in the church exemplify a transition of Byzantine art periods, from Komnenian to Palaiologan, as many paintings were completed between 1263-1268. The Dormition, with its stately compositions and monumental figures, is an example of this.[4] The period following iconoclasm brought upon a resurgence in these art styles moving forward into the 13th century, at the time of the construction of the monastery. Other motifs seen in the church (such as water-birds and use of specific lotuses) are indicative of influences from early Byzantine art dating to the era of Justinian I, although these influences are less prominently featured in the church.[5]

The implementation of this art can be separated into several distinct periods. In 1263-1268, various paintings, including those of the sons of Stefan Uroš I, Dragutin, and Milutin, were created. In 1331-1346, during the reign of King Stefan Dušan, the church expanded and took on characteristics of a cathedral, expanding the art and decorations seen in the exo-narthex of the church.[6] In 1335-1371, it is presumed that the fresco paintings of the church were completed, evidenced by painting styles seen in other nearby churches. In 1370-1375, the first example of repainting was evidenced in the church, and the copying of Sopoćani works created the Sopoćani style which spread and influenced other church paintings.[7] And in the early 20th century, the art of Sopoćani served as an inspiration for modern Serbian artists.[8]

Art reconstruction

In 1689, various factors contributed to widespread damage through the church. War with the Ottoman Turks led to the desecration of the monastery. In addition, inclement weather and prolonged sun exposure led to damage of much of the art. There were two periods in the early 20th century (1925-1929, and 1949-1958) in which reconstruction campaigns began on a large scale. Notably, the color and clarity of the paintings were restored, but much of the gold-leaf outlines remain difficult to discern in the frescoes of the church.[9]

Notable art and techniques

Paintings

The frescoes in Sopoćani were painted in a similar style to that of Byzantine artists, however the origins of the artists themselves remain unknown.[10] There was a rigid set of steps (setting of plaster, designing with charcoal, application of opsis in various layers, etc.) that were usually followed by these artists. However, there were exceptions to this method, as is the case with the Dormition, which was painted over visible division lines that are usually erased. Some historians believe this to be the result of an oversight on the part of the artist.[11] The Dormition is another example of a late Komnenian fresco, characterized by its use of a rambling narrative linear style.[12] Some of the more prominent frescoes in the church had gold-sheet tesserae applied in their outlines, a decision that was made by Stefan Uroš I to provide a greater sense of visual grandeur.[13]

Iconography

A demand was created for portable icons due to Byzantine influence and the introduction of iconostasis in churches.[14] The icons in Sopoćani largely represent a matriarchal ideology, depicting the life and death of the Virgin Mary, among others.[15] The portraits of these icons incorporated techniques and symbolism from Byzantine, and earlier Roman style, which emphasizes the positioning of the head, as well as male and female qualities of the hands. For instance, the left hand would often be considered female, holding books or scriptures. The right hand would be considered male, holding a sword, a cross, or a spear.[16] These qualities can be seen in icon plates of the martyrs, saints, apostle, and evangelist in Sopoćani. The portrayal of figures in these icons are also concurrent with the development of naturalism in painting, found in other Byzantine icons and mosaics such as the Deisis in Hagia Sophia.[17]

Gallery

Monastery building.

Detail of the fresco Dormition of the Mother of God from Sopoćani c. 1265

Detail of the fresco Dormition of the Mother of God.

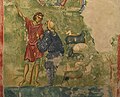

Stefan Uroš I with his son Dragutin

Shepherd

Burials

- Stefan Uroš I of Serbia

- Anna Dandolo

- Joanikije I

In popular culture

Sopoćani, two episodes of the documentary series "Witnesses of Times" produced by the broadcasting service RTB in 1999-2000 was created by Petar Savkovića, directed by Stevan Stanić and Radoslav Moskovlović, music was composed by Zoran Hristić.[18][19]

See also

- Studenica

- Žiča

- Mileševa

- Visoki Dečani

- Gračanica

- Nemanjić dynasty

- Spatial Cultural-Historical Units of Great Importance

References

^ By Their Fruit you will recognize them - Christianization of Serbia in Middle Ages, Perica Speher, 2010.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 25. ISBN 81-208-0990-4..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Rajković, Mila (1967). Sopoćani. Beograd, "Jugoslavija". p. 6.

^ Kazhdan, Alexander; Talbot, Alice-Mary; Cutler, Anthony; Gregory, Timothy; Sevcenko, Nancy (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1929.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 283. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 28. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 29. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 30. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Rajković, Mila (1967). Sopoćani. Beograd, "Jugoslavija". p. 5.

^ Kazhdan, Alexander; Talbot, Alice-Mary; Cutler, Anthony; Gregory, Timothy; Sevcenko, Nancy (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1929.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 214. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Kazhdan, Alexander; Talbot, Alice-Mary; Cutler, Anthony; Gregory, Timothy; Sevcenko, Nancy (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1929.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 215. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Schug-Wille, Christa (1969). Art of the Byzantine World. New York: Abrams. p. 210.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 214. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Upadhya, Om. The art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A comparative study: An enquiry in prāṇa aesthetics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 150. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

^ Cormack, Robin (2000). Byzantine Art. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-19-284211-4.

^ Sopoćani - first episode on YouTube Official channel of RTS

^ Sopoćani - second episode on YouTube Official channel of RTS

Sopoćani, Vojislav Đurić, Prosveta, Beograd, 1991.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sopoćani. |

- Official website

- BLAGO Fund: Sopoćani

- Aerial video of the Sopoćani

- Sopoćani and Gradac - About the relation of funerary programmes of the two churches by Branislav Todić

- Representations of Lancet or Phlebotome in Serbian Medieval Art