Warring States period

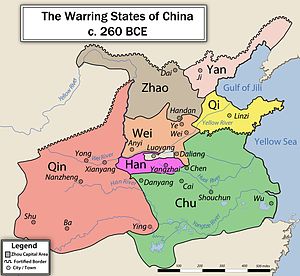

Map showing states at the beginning of Warring States period of Zhou Dynasty in Chinese history

| Warring States period | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Warring States" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 戰國時代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 战国时代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhànguó Shídài | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Warring States era" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ANCIENT | |||||||

Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | |||||||

Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | |||||||

Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | |||||||

Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BC | |||||||

| Western Zhou | |||||||

| Eastern Zhou | |||||||

| Spring and Autumn | |||||||

| Warring States | |||||||

IMPERIAL | |||||||

Qin 221–206 BC | |||||||

Han 202 BC – 220 AD | |||||||

| Western Han | |||||||

| Xin | |||||||

| Eastern Han | |||||||

Three Kingdoms 220–280 | |||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | |||||||

Jin 265–420 | |||||||

| Western Jin | |||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | ||||||

Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | |||||||

Sui 581–618 | |||||||

Tang 618–907 | |||||||

| (Second Zhou 690–705) | |||||||

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 | Liao 907–1125 | ||||||

Song 960–1279 | |||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | ||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | ||||||

Yuan 1271–1368 | |||||||

Ming 1368–1644 | |||||||

Qing 1636–1912 | |||||||

MODERN | |||||||

Republic of China 1912–1949 | |||||||

People's Republic of China 1949–present | |||||||

Related articles

| |||||||

The Warring States period (Chinese: 戰國時代; pinyin: Zhànguó Shídài) was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest that saw the annexation of all other contender states, which ultimately led to the Qin state's victory in 221 BC as the first unified Chinese empire, known as the Qin dynasty. Although different scholars point toward different dates ranging from 481 BC to 403 BC as the true beginning of the Warring States, Sima Qian's choice of 475 BC is the most often cited. The Warring States era also overlaps with the second half of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, though the Chinese sovereign, known as the king of Zhou, ruled merely as a figurehead and served as a backdrop against the machinations of the warring states.

The "Warring States Period" derives its name from the Record of the Warring States, a work compiled early in the Han dynasty.

Much later, Japanese historians—well versed in Chinese culture—used the term Warring States period for the Sengoku period of their own history.

Contents

1 Geography

2 Periodisation

3 Background and formation

3.1 Partition of Jin (453–403 BC)

4 Early Warring States

4.1 The three Jins recognized (403–364 BC)

4.2 Qi resurgence under Tian (379–340 BC)

4.3 Wars of Wei

5 Dukes become kings

5.1 Qi and Wei become kings (344 BC)

5.2 Shang Yang reforms Qin (356–338 BC)

5.3 Wei defeated by Qin (341–340 BC)

5.4 Chu conquers Yue (334 BC)

5.5 Qin, Han and Yan become kings (325–323 BC)

5.6 Partition of Zhou (314 BC)

6 Horizontal and vertical alliances (334–249 BC)

6.1 Su Qin and the first vertical alliance (334–300 BC)

6.2 The first horizontal alliance (300–287 BC)

6.3 Su Dai and the second vertical alliance

6.4 The second horizontal alliance

6.5 Qin vs Zhao (278–260 BC)

6.6 End of Zhou dynasty (256–249 BC)

7 Qin unites China (247–221 BC)

7.1 Conquest of Han

7.2 Conquest of Wei

7.3 Conquest of Chu

7.4 Conquest of Zhao and Yan

7.5 Conquest of Qi

8 Military theory and practice

8.1 Increasing scale of warfare

8.2 Military developments

8.3 Military thought

9 Culture and society

9.1 Nobles, bureaucrats and reformers

9.2 Sophisticated arithmetic

10 Literature

11 Economic developments

12 See also

13 References

13.1 Citations

13.2 Sources

14 Further reading

15 External links

Geography

The political geography of the era was dominated by the Seven Warring States, namely:

Qin located in the far west, with its core in the Wei River Valley and Guanzhong. This geographical position offered protection from the other states but limited its initial influence.

The Three Jins Located in the center on the Shanxi plateau were the three successor states of Jin. These were:

Han south, along the Yellow River, controlling the approaches to Qin.

Wei located in the middle, roughly today's eastern Henan Province.

Zhao the northernmost of the three, roughly today's southern Hebei Province as well as northern Shanxi Province.

Qi east, centred on the Shandong Peninsula

Chu south, with its core territory around the valleys of the Han River and, later, the Yangtze River.

Yan northeast, centred on modern-day Beijing. Late in the period it pushed northeast and began to occupy the Liaodong Peninsula

Besides these seven major states other smaller states survived into the period. They include:

Royal territory of the Zhou king was near Luoyi in the Han area on the Yellow River.

Yue On the southeast coast near Shanghai was the State of Yue, which was highly active in the late Spring and Autumn era but was later annexed by Chu.

Zhongshan Between the states of Zhao and Yan was the state of Zhongshan, which was eventually annexed by Zhao in 296 BC.

Sichuan states: In the far southwest were the non-Zhou states of Ba (east) and Shu (west). These ancient kingdoms were conquered by Qin later in the period.

Other minor states: There were many minor states which were satellites of the larger ones until they were absorbed. Many were in the Central Plains between the three Jins (west) and Qi (east) and Chu to the south. Some of the more important ones were Song, Lu, Zheng, Wey, Teng and Zou.

Periodisation

The eastward flight of the Zhou court in 771 BC marks the start of the Spring and Autumn period. No one single incident or starting point inaugurated the Warring States era. The political situation of the period represented a culmination of historical trends of conquest and annexation which also characterised the Spring and Autumn period; as a result there is some controversy as to the beginning of the era. Proposed starting points include:

- 481 BC

Proposed by Song-era historian Lü Zuqian, also known as Lü Bogong, since this year marks the end of the Spring and Autumn Annals. - 476–475 BC

The author, Sima Qian, of Records of the Grand Historian, chose this date as the inaugural year of King Yuan of Zhou. - 453 BC

The Partition of Jin saw the dissolution/destruction of that key state of the earlier period and the formation of three of the seven warring states: Han, Zhao, and Wei. - 441 BC

The inaugural year of Zhou Kings starting with King Ai of Zhou. - 403 BC

The year when the Zhou court officially recognised Han, Zhao and Wei as states. Author Sima Guang of Zizhi Tongjian (published 1084) advocates this symbol of eroded Zhou authority as the start of the Warring States era.

Background and formation

Warring States about early-4th century BC

The Eastern Zhou Dynasty began to fall around 5th century BC. They had to rely on other armies in other allied states because their military rule no longer followed. Over 100 smaller states were made into 7 major states which included: Chu, Han, Qin, Wei, Yan, Qi and Zhao. However, there eventually was a shift in alliances because each state's ruler wanted to be independent in power. This caused hundreds of wars between the periods of 535-286 BCE. The victorious state would have overall rule and control in China.[1]

The system of feudal states created by the Western Zhou dynasty underwent enormous changes after 771 BC with the flight of the Zhou court to modern-day Luoyang and the diminution of its relevance and power. The Spring and Autumn period led to a few states gaining power at the expense of many others, the latter no longer able to depend on central authority for legitimacy or protection.

During the Warring States period, many rulers claimed the Mandate of Heaven to justify their conquest of other states and spread their influence.[2]

The struggle for hegemony eventually created a state system dominated by several large states, such as Jin, Chu, Qin and Qi, while the smaller states of the Central Plains tended to be their satellites and tributaries. Other major states also existed, such as Wu and Yue in the southeast. The last decades of the Spring and Autumn era were marked by increased stability, as the result of peace negotiations between Jin and Chu which established their respective spheres of influence. This situation ended with the partition of Jin, whereby the state was divided between the houses of Han, Zhao and Wei, and thus enabled the creation of the seven major warring states.

Partition of Jin (453–403 BC)

The rulers of Jin had steadily lost political powers since the middle of the 6th century BC to their nominally subordinate nobles and military commanders, a situation arising from the traditions of the Jin which forbade the enfeoffment of relatives of the ducal house. This allowed other clans to gain fiefs and military authority, and decades of internecine struggle led to the establishment of four major families, the Han, Zhao, Wei and Zhi.

The Battle of Jinyang saw the allied Han, Zhao and Wei destroy the Zhi family (453 BC) and their lands were distributed among them. With this, they became the "de facto" rulers of most of Jin's territory, though this situation would not be officially recognised until half a century later. The Jin division created a political vacuum that enabled during the first 50 years expansion of Chu and Yue northward and Qi southward. Qin increased its control of the local tribes and began its expansion southwest to Sichuan.

Early Warring States

The three Jins recognized (403–364 BC)

Tomb Guardian of Chu Kingdom (300 BC) held at Birmingham Museum of Art

In 403 BC, the Zhou court under King Weilie officially recognized Zhao, Wei and Han as immediate vassals, thereby raising them to the same rank as the other warring states.

From before 405 until 383 the three Jins were united under the leadership of Wei and expanded in all directions. The most important figure was Marquess Wen of Wei (445–396). In 408–406 he conquered the State of Zhongshan to the northeast on the other side of Zhao. At the same time he pushed west across the Yellow River to the Luo River taking the area of Xihe (literally 'west of the [Yellow] river').

The growing power of Wei caused Zhao to back away from the alliance. In 383 it moved its capital to Handan and attacked the small state of Wey. Wey appealed to Wei which attacked Zhao on the western side. Being in danger, Zhao called in Chu. As usual, Chu used this as a pretext to annex territory to its north, but the diversion allowed Zhao to occupy a part of Wei. This conflict marked the end of the power of the united Jins and the beginning a period of shifting alliances and wars on several fronts.

In 376 BC, the states of Han, Wei and Zhao deposed Duke Jing of Jin and divided the last remaining Jin territory between themselves, which marked the final end of the Jin state.

In 370 BC, Marquess Wu of Wei died without naming a successor, which led to a war of succession. After three years of civil war, Zhao from the north and Han from the south invaded Wei. On the verge of conquering Wei, the leaders of Zhao and Han fell into disagreement about what to do with Wei, and both armies abruptly retreated. As a result, King Hui of Wei (still a Marquess at the time) was able to ascend the throne of Wei.

By the end of the period Zhao extended from the Shanxi plateau across the plain to the borders of Qi. Wei reached east to Qi, Lu and Song. To the south, the weaker state of Han held the east-west part of the Yellow River valley, surrounded the Zhou royal domain at Luoyang and held an area north of Luoyang called Shangdang.

Qi resurgence under Tian (379–340 BC)

A carved-jade dragon garment ornament from the Warring States period

Duke Kang of Qi died in 379 BC with no heir from the house of Jiang, which had ruled Qi since the state's founding. The throne instead passed to the future King Wei, from the house of Tian. The Tian had been very influential at court towards the end of Jiang rule, and now openly assumed power.[3]

The new ruler set about reclaiming territories that had been lost to other states. He launched a successful campaign against Zhao, Wey and Wei, once again extending Qi territory to the Great Wall. Sima Qian writes that the other states were so awestruck that nobody dared attack Qi for more than 20 years. The demonstrated military prowess also had a calming effect on Qi's own population, which experienced great domestic tranquility during Wei's reign.[4]

By the end of King Wei's reign, Qi had become the strongest of the states and proclaimed itself "king"; establishing independence from the Zhou dynasty (see below).

Wars of Wei

A jade-carved huang with two dragon heads, Warring States, Shanghai Museum

King Hui of Wei (370–319 BC) set about restoring the state. In 362–359 BC he exchanged territories with Han and Zhao in order to make the boundaries of the three states more rational.

In 364 BC Wei was defeated by Qin at the Battle of Shimen and was only saved by the intervention of Zhao. Qin won another victory in 362 BC. In 361 BC the Wei capital was moved east to Daliang to be out of the reach of Qin.

In 354 BC, King Hui of Wei started a large-scale attack on Zhao. By 353 BC, Zhao was losing badly and its capital, Handan, was under siege. The State of Qi intervened. The famous Qi strategist, Sun Bin the great-great-great-grandson of Sun Tzu (author of the Art of War), proposed to attack the Wei capital while the Wei army was tied up besieging Zhao. The strategy was a success; the Wei army hastily moved south to protect its capital, was caught on the road and decisively defeated at the Battle of Guiling. The battle is remembered in the second of the Thirty-Six Stratagems, "besiege Wei, save Zhao" meaning to attack a vulnerable spot to relieve pressure at another point.

Domestically, King Hui patronized philosophy and the arts, and is perhaps best remembered for hosting the Confucian philosopher Meng Zi at his court; their conversations form the first two chapters of the book which bears Meng Zi's name.

Dukes become kings

Chu Painting on silk depicting a man riding a dragon from Zidanku Tomb no. 1 in Changsha, Hunan Province (5th-3rd century BC).

Qi and Wei become kings (344 BC)

The title of "king" (wang, 王) was held by figurehead rulers of the Zhou dynasty, while the rulers of most states held the title of "duke" (gong, 公) or "marquess" (hou, 侯). A major exception was Chu, whose rulers were called kings since King Wu of Chu started using the title c. 703 BC.

In 344 BC the rulers of Qi and Wei mutually recognized each other as "kings": King Wei of Qi and King Hui of Wei, in effect declaring their independence from the Zhou court. This marked a major turning point: unlike those in the Spring and Autumn period, the new generation of rulers ascending the thrones in the Warring States period would not entertain even the pretence of being vassals of the Zhou dynasty, instead proclaiming themselves fully independent kingdoms.

Shang Yang reforms Qin (356–338 BC)

The Bianzhong of Marquis Yi of Zeng, a set of bronze bianzhong percussion instruments from the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng in Hubei province (433 BC).

During the early Warring States period Qin generally avoided conflicts with the other states. This changed during the reign of Duke Xiao, when prime minister Shang Yang made centralizing and authoritarian reforms in accordance with his Legalist philosophy between the years 356 and 338 BC.

Shang introduced land reforms, privatized land, rewarded farmers who exceeded harvest quotas, enslaved farmers who failed to meet quotas, and used enslaved subjects as rewards for those who met government policies. As manpower was short in Qin relative to the other states at the time, Shang enacted policies to increase its manpower. As Qin peasants were recruited into the military, he encouraged active immigration of peasants from other states into Qin as a replacement workforce; this policy simultaneously increased the manpower of Qin and weakened the manpower of Qin's rivals.

Shang made laws forcing citizens to marry at a young age and passed tax laws to encourage raising multiple children. He also enacted policies to free convicts who worked in opening wastelands for agriculture. Shang abolished primogeniture and created a double tax on households that had more than one son living in the household, to break up large clans into nuclear families. Shang also moved the capital to reduce the influence of nobles on the administration.

The rise of Qin was recognized by the royal court, and in 343 BC the king conferred the title of hegemon on Duke Xiao. As was customary for the designated hegemon, the duke hosted a conference of all the feudal lords, although it did not lead to any lasting peace.[3]

After the reforms Qin became much more aggressive. In 340 Qin took land from Wèi after it had been defeated by Qi. In 316 Qin conquered Shu and Ba in Sichuan to the southwest. Development of this area took a long time but slowly added greatly to Qin's wealth and power.

Wei defeated by Qin (341–340 BC)

In 341 BC, Wei attacked Han. Qi allowed Han to be nearly defeated and then intervened. The generals from the Battle of Guiling met again (Sun Bin and Tian Ji versus Pang Juan), using the same tactic, attacking Wei's capital. Sun Bin feigned a retreat and then turned on the overconfident Wei troops and decisively defeated them at the Battle of Maling. After the battle all three of the Jin successor states appeared before King Xuan of Qi, pledging their loyalty.[5]

In the following year Qin attacked the weakened Wei. Wei was devastatingly defeated and ceded a large part of its territory in return for truce. With Wei severely weakened, Qi and Qin became the dominant states in China.

Wei came to rely on Qi for protection, with King Hui of Wei meeting King Xuan of Qi on two occasions. After Hui's death, his successor King Xiang also established a good relationship with his Qi counterpart, with both promising to recognize the other as "king".[4]

Chu conquers Yue (334 BC)

A Warring States bronze ding vessel with gold and silver inlay

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓;; pinyin: Jīngmén chǔ mù) of the State of Chu (704–223 BC), depicting men wearing precursors to Hanfu (i.e. traditional silk dress) and riding in a two-horsed chariot

Early in the Warring States period, Chu was one of the strongest states in China. The state rose to a new level of power around 389 BC when King Dao of Chu (楚悼王) named the famous reformer Wu Qi as his chancellor.

Chu rose to its peak in 334 BC, when it conquered Yue to its east on the Pacific coast. The series of events leading up to this began when Yue prepared to attack Qi to its north. The King of Qi sent an emissary who persuaded the King of Yue to attack Chu instead. Yue initiated a large-scale attack at Chu but was defeated by Chu's counter-attack. Chu then proceeded to conquer Yue.

Qin, Han and Yan become kings (325–323 BC)

King Xian of Zhou had attempted to use what little royal prerogrative he had left by appointing the dukes Xian (384-362 BC), Xiao (361-338 BC) and Hui (338-311 BC) of Qin as hegemons, thereby in theory making Qin the chief ally of the court.[6]

However, in 325 the confidence of Duke Hui grew so great that he proclaimed himself "king" of Qin; adopting the same title as the king of Zhou and thereby effectively proclaiming independence from the Zhou dynasty.[6] King Hui of Qin was guided by his prime minister Zhang Yi, a prominent representative of the School of Diplomacy.[7]

He was followed in 323 BC by King Xuanhui of Han and King Yi of Yan, as well as King Cuo of the minor state Zhongshan.[3] In 318 BC, even the ruler of Song, a relatively minor state, declared himself king. Uniquely, while King Wuling of Zhao had joined the other kings in declaring himself king, he retracted this order in 318 BC, after Zhao suffered a great defeat in the hands of Qin.

Partition of Zhou (314 BC)

King Kao of Zhou had enfeoffed his younger brother as Duke Huan of Henan. Three generations later, this cadet branch of the royal house began calling themselves "Dukes of East Zhou".[6]

Upon the ascension of King Nan in 314 BC, East Zhou became an independent state. The king came to reside in what became known as West Zhou.[6]

Horizontal and vertical alliances (334–249 BC)

Rectangular lacquered shield from the Warring States Period. Found in Baoshan Tomb 2, Jingmen.

An iron sword and two bronze swords dated to the Warring States period

Towards the end of the Warring States period, the Qin state became disproportionately powerful compared with the other six states. As a result, the policies of the six states became overwhelmingly oriented towards dealing with the Qin threat, with two opposing schools of thought. One school advocated a 'vertical' or north-south alliance called hezong (合縱/合纵) in which the states would ally with each other to repel Qin. The other advocated a 'horizontal' or east-west alliance called lianheng (連橫/连横) in which a state would ally with Qin to participate in its ascendancy.

There were some initial successes in hezong, though mutual suspicions between allied states led to the breakdown of such alliances. Qin repeatedly exploited the horizontal alliance strategy to defeat the states one by one. During this period, many philosophers and tacticians travelled around the states, recommending that the rulers put their respective ideas into use. These "lobbyists," such as Su Qin (who advocated vertical alliances) and Zhang Yi (who advocated horizontal alliances), were famous for their tact and intellect, and were collectively known as the School of Diplomacy, whose Chinese name (縱橫家, literally 'the school of the vertical and horizontal') was derived from the two opposing ideas.

Su Qin and the first vertical alliance (334–300 BC)

Beginning in 334 BC, the diplomat Su Qin spent years visiting the courts of Yan, Zhao, Han, Wei, Qi and Chu and persuaded them to form a united front against Qin. In 318 BC all states except Qi launched a joint attack on Qin, which however was not successful.[3]

King Hui of Qin died in 311 BC, followed by prime minister Zhang Yi one year later. The new monarch, King Wu, reigned only four years before dying without legitimate heirs. Some damaging turbulence ensued throughout 307 BC before a son of King Hui by a concubine (i.e. a younger half-brother of King Wu) could be established as King Zhao, who in stark contrast to his predecessor went on to rule for an unprecedented 53 years.

After the failure of the first vertical alliance, Su Qin eventually came to live in Qi, where he was favored by King Xuan and drew the envy of the ministers. An assassination attempt in 300 BC left Su mortally wounded but not dead. Sensing death approaching, he advised the newly crowned King Min have him publicly executed to draw out the assassins. King Min complied with Su's request and killed him, putting an end to the first generation of Vertical alliance thinkers.[8]

The first horizontal alliance (300–287 BC)

A bronze statue of a seated man, from the State of Yue, Warring States period

King Min of Qi came to be highly influenced by Lord Mengchang, a grandson of the former King Wei of Qi. Lord Mengchang made a westward alliance with the States of Wei and Han. In the far west, Qin, which had been weakened by a succession struggle in 307, yielded to the new coalition and appointed Lord Mengchang its chief minister. The alliance between Qin and Qi was sealed by a Qin princess marrying King Min.[4] This "horizontal" or east-west alliance might have secured peace except that it excluded the State of Zhao.

Around 299 BC, the ruler of Zhao became the last of the seven major states to proclaim himself "king".

In 298 BC Zhao offered Qin an alliance and Lord Mengchang was driven out of Qin. The remaining three allies, Qi, Wei and Han, attacked Qin, driving up the Yellow River below Shanxi to the Hangu Pass. After 3 years of fighting they took the pass and forced Qin to return territory to Han and Wei. They next inflicted major defeats on Yan and Chu. During the 5-year administration of Lord Mengchang, Qi was the major power in China.

In 294 BC Lord Mengchang was implicated in a coup d'etat and fled to Wei. His alliance system collapsed.

Qi and Qin made a truce and pursued their own interests. Qi moved south against the State of Song whilst the Qin General Bai Qi pushed back eastward against a Han/Wei alliance, gaining victory at the Battle of Yique.

In 288 BC King Zhao of Qin and King Min of Qi took the title "Di", (帝 literally emperor), of the west and east respectively. They swore a covenant and started planning an attack on Zhao.

Su Dai and the second vertical alliance

In 287 BC Su Dai, the younger brother of Su Qin[8] and possibly an agent of Yan, persuaded King Min that the Zhao war would only benefit Qin. King Min agreed and formed a 'vertical' alliance with the other states against Qin. Qin backed off, abandoned the presumptuous title of "Di", and restored territory to Wei and Zhao. In 286 Qi annexed the state of Song.

The second horizontal alliance

In 285 BC the success of Qi had frightened the other states. Under the leadership of Lord Mengchang, who was exiled in Wei, Qin, Zhao, Wei and Yan formed an alliance. Yan had normally been a relatively weak ally of Qi and Qi feared little from this quarter. Yan's onslaught under general Yue Yi came as a devastating surprise. Simultaneously, the other allies attacked from the west. Chu declared itself an ally of Qi but contented itself with annexing some territory to its north. Qi's armies were destroyed while the territory of Qi was reduced to the two cities of Ju and Jimo. King Min himself was later captured and executed by his own followers.

King Min was succeeded by King Xiang in 283 BC. His general Tian Dan was eventually able to restore much of Qi's territory, but it never regained the influence it had under King Min.

Qin vs Zhao (278–260 BC)

Seven Warring States late in the period

Qin has expanded southwest, Chu north and Zhao northwest

General Bai Qi of Qin attacked from Qin's new (from 316) territory in Sichuan to the west of Chu. The capital of Ying was captured and Chu's western lands on the Han River were lost. The effect was to shift Chu significantly to the east.

After Chu was defeated in 278, the remaining great powers were Qin in the west and Zhao in the north-center. There was little room for diplomatic maneuver and matters were decided by war in 265–260. Zhao had been much strengthened by King Wuling of Zhao (325–299). In 307 he enlarged his cavalry by copying the northern nomads. In 306 he took more land in the northern Shanxi plateau. In 305 he defeated the northeastern border state of Zhongshan. In 304 he pushed far to the northwest and occupied the east-west section of the Yellow River in the north of the Ordos Loop. King Huiwen of Zhao (298–266) chose able servants and expanded against the weakened Qi and Wei. In 296 his general Lian Po defeated two Qin armies.

In 269 BC Fan Sui became chief advisor to Qin. He advocated authoritarian reforms, irrevocable expansion and an alliance with distant states to attack nearby states (the twenty-third of the Thirty-Six Stratagems). His maxim "attack not only the territory, but also the people" enunciated a policy of mass slaughter that became increasingly frequent.[citation needed]

In 265 King Zhaoxiang of Qin made the first move by attacking the weak state of Han which held the Yellow River gateway into Qin. He moved northeast across Wei territory to cut off the Han exclave of Shangdang north of Luoyang and south of Zhao. The Han king agreed to surrender Shangdang, but the local governor refused and presented it to King Xiaocheng of Zhao. Zhao sent out Lian Po who based his armies at Changping and Qin sent out general Wang He. Lian Po was too wise to risk a decisive battle with the Qin army and remained inside his fortifications. Qin could not break through and the armies were locked in stalemate for three years. The Zhao king decided that Lian Po was not aggressive enough and sent out Zhao Kuo who promised a decisive battle. At the same time Qin secretly replaced Wang He with the notoriously violent Bai Qi. When Zhao Kuo left his fortifications, Bai Qi used a Cannae maneuver, falling back in the center and surrounding the Zhao army from the sides. After being surrounded for 46 days, the starving Zhao troops surrendered in September 260 BC. It is said that Bai Qi had all the prisoners killed and that Zhao lost 400,000 men.

Qin was too exhausted to follow up its victory. Some time later it sent an army to besiege the Zhao capital but the army was destroyed when it was attacked from the rear. Zhao survived, but there was no longer a state that could resist Qin on its own. The other states could have survived if they remained united against Qin, but they did not.

End of Zhou dynasty (256–249 BC)

The forces of King Zhao of Qin defeated King Nan of Zhou and conquered West Zhou in 256 BC, claiming the Nine Cauldrons and thereby symbolically becoming The Son of Heaven.

King Zhao's exceptionally long reign ended in 251 BC. His son King Xiaowen, already an old man, died just three days after his coronation and was succeeded by his son King Zhuangxiang of Qin. The new Qin king proceeded to conquer East Zhou, seven years after the fall of West Zhou. Thus the 800-year Zhou dynasty, nominally China's longest-ruling regime, finally came to an end.[6]

Sima Qian contradicts himself regarding the ultimate fate of the East Zhou court. Chapter 4 (The Annals of Zhou) concludes with the sentence "thus the sacrifices of Zhou ended", but in the following chapter 5 (The Annals of Qin) we learn that "Qin did not prohibit their sacrifices; the Lord of Zhou was allotted a patch of land in Yangren where he could continue his ancestral sacrifices".

Qin unites China (247–221 BC)

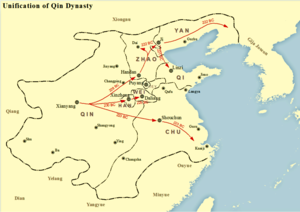

Animated map of the Warring States period[9]

Unification of Qin from 230 BC to 211 BC

King Zhuangxiang of Qin ruled for only three years. He was succeeded by his son Zheng, who unlike the two elderly kings that preceded him was only 13 years old at his coronation. As an adult Zheng would turn out to be a brilliant commander who, in the span of just nine years, unified China.[7]

Conquest of Han

In 230 BC, Qin conquered Han.[10]

Han, the weakest of the Seven Warring States, was adjacent to the much stronger Qin, and had suffered continuous assaults by Qin in earlier years of the Warring States period. This went on until Emperor Qin Shi Huang sent general Wang Jian to attack Zhao. King An of Han, frightened by the thought that Han would be the next target of the Qin state, immediately sent diplomats to surrender the entire kingdom without a fight, saving the Han populace from the terrible potential consequences of an unsuccessful resistance.

Conquest of Wei

In 225 BC, Qin conquered Wei.

The Qin army led a direct invasion into Wei by besieging its capital Daliang but soon realized that the city walls were too tough to break into. They devised a new strategy in which they utilized the power of a local river that was linked to the Yellow River. The river was used to flood the city's walls, causing massive devastation to the city. Upon realizing the situation, King Jia of Wei hurriedly came out of the capital and surrendered it to the Qin army in order to avoid further bloodshed of his people.

Conquest of Chu

A drinking cup carved from crystal, unearthed at Banshan, Hangzhou, Warring States period, Hangzhou Museum.

In 223 BC, Qin conquered Chu.

The first invasion was however an utter disaster when 200,000 Qin troops, led by the general, Li Xin, were defeated by 500,000 Chu troops in the unfamiliar territory of Huaiyang, modern-day northern Jiangsu and Anhui provinces. Xiang Yan, the Chu commander, had lured Qin by allowing a few initial victories, but then counterattacked and burnt two large Qin camps.

In 222 BC, Wang Jian was recalled to lead a second military invasion with 600,000 men against the Chu state. High in morale after their victory in the previous year, the Chu forces were content to sit back and defend against what they expected to be a siege of Chu. However, Wang Jian decided to weaken Chu's resolve and tricked the Chu army by appearing to be idle in his fortifications whilst secretly training his troops to fight in Chu territory. After a year, the Chu defenders decided to disband due to apparent lack of action from the Qin. Wang Jian invaded at that point, with full force, and overran Huaiyang and the remaining Chu forces. Chu lost the initiative and could only sustain local guerrilla-style resistance until it too was fully conquered with the destruction of Shouchun and the death of its last leader, Lord Changping, in 223 BC. At their peak, the combined armies of Chu and Qin are estimated to have ranged from hundreds of thousands to a million soldiers, more than those involved in the campaign of Changping between Qin and Zhao 35 years earlier.[11]

Conquest of Zhao and Yan

In 222 BC, Qin conquered Zhao and Yan.

After the conquest of Zhao, the Qin army turned its attention towards Yan. Realizing the danger and gravity of this situation, Crown Prince Dan of Yan had sent Jing Ke to assassinate King Zheng of Qin, but this failure only helped to fuel the rage and determination of the Qin king, and he increased the number of troops to conquer the Yan state.

Conquest of Qi

In 221 BC, Qin conquered Qi.

Qi was the final unconquered warring state. It had not previously contributed or helped other states when Qin was conquering them. As soon as Qin's intention to invade it became clear, Qi swiftly surrendered all its cities, completing the unification of China and ushering in the Qin dynasty. The last Qi king lived out his days in exile in Gong and was not given a posthumous name after death, therefore he is known to posterity by his personal name Jian.

The Qin king Zheng declared himself Qin Shi Huangdi, “The first Sovereign Emperor of Qin".[10]

In the rule of the Qin state, the union was based solely on military power. The feudal holdings were abolished, and noble families were forced to live in the capital of China, Xianyang in order to be supervised. A national road as well as greater use of canals was used in order for deployment and supply of the army to be done with ease and speed. The peasants were given a wider range of rights in regards of land, although they were subject to taxation, creating a large amount of revenue to the state.[10]

Military theory and practice

Iron sword of the Period of Warring States.

A Chinese soldier's bronze helmet, from the State of Yan, dated to the Zhou Dynasty.

Model of a Warring States period traction trebuchet.

Increasing scale of warfare

The chariot remained a major factor in Chinese warfare long after it went out of fashion in the Middle East. Near the beginning of the Warring States period there is a shift from chariots to massed infantry, possibly associated with the invention of the crossbow. This had two major effects. First it led the dukes to weaken their chariot-riding nobility so they could get direct access to the peasantry who could be drafted as infantry. This change was associated with the shift from aristocratic to bureaucratic government. Second, it led to a massive increase in the scale of warfare. When the Zhou overthrew the Shang at the Battle of Muye they used 45,000 troops and 300 chariots. For the Warring States period the following figures for the military strengths of various states are reported:

- Qin

1,000,000 infantry, 1,000 chariots, 10,000 horses; - Chu

same numbers; - Wei

200–360,000 infantry, 200,000 spearmen, 100,000 servants, 600 chariots, 5,000 cavalry; - Han

300,000 total; - Qi

several hundred thousand;

For major battles, the following figures are reported:

Battle of Maling

100,000 killed;

Battle of Yique

240,000 killed;- General Bai Qi is said to have been responsible for 890,000 enemy deaths over his career.

Many scholars think these numbers are exaggerated (records are inadequate, they are much larger than those from similar societies, soldiers were paid by the number of enemies they killed and the Han dynasty had an interest in exaggerating the bloodiness of the age before China was unified). Regardless of exaggeration, it seems clear that warfare had become excessive during this period. The bloodshed and misery of the Warring States period goes a long way in explaining China's traditional and current preference for a united throne.[12]

Military developments

The Warring States period saw the introduction of many innovations to the art of warfare in China, such as the use of iron and of cavalry.

Warfare in the Warring States period evolved considerably from the Spring and Autumn period, as most armies made use of infantry and cavalry in battles, and the use of chariots became less widespread. The use of massed infantry made warfare bloodier and reduced the importance of the aristocracy, which in turn made the kings more despotic. From this period onward, as the various states competed with each other by mobilizing their armies to war, nobles in China belonged to the literate class, rather than to the warrior class as had previously been the case.

The various states fielded massive armies of infantry, cavalry, and chariots. Complex logistical systems maintained by efficient government bureaucracies were needed to supply, train, and control such large forces. The size of the armies ranged from tens of thousands to several hundred thousand men.[13]

Iron weapons became more widespread and began to replace bronze. Most armour and weapons of this period were made from iron.

The first official native Chinese cavalry unit was formed in 307 BC during the military reforms of King Wuling of Zhao, who advocated 'nomadic dress and horse archery'.[14] But the war chariot still retained its prestige and importance, despite the tactical superiority of cavalry.

The crossbow was the preferred long-range weapon of this period, due to several reasons. The crossbow could be mass-produced easily, and mass training of crossbowmen was possible. These qualities made it a powerful weapon against the enemy.

Infantrymen deployed a variety of weapons, but the most popular was the dagger-axe. The dagger-axe came in various lengths, from 9 to 18 feet; the weapon consisted of a thrusting spear with a slashing blade appended to it. Dagger-axes were an extremely popular weapon in various kingdoms, especially for the Qin, who produced 18-foot-long pike-like weapons.

Military thought

The Warring States was a great period for military strategy; of the Seven Military Classics of China, four were written during this period:

The Art of War

It is attributed to Sun Tzu, a highly influential study of strategy and tactics.[15]

Wuzi

It is attributed to Wu Qi, a statesman and commander who served the states of Wei and then Chu.

Wei Liaozi

of uncertain authorship.

The Methods of the Sima

It is attributed to Sima Rangju, a commander serving the state of Qi.

Culture and society

A Chinese lacquerware drinking vessel (over wood), Warring States period, Honolulu Museum of Art

A nephrite pendant in the shape of a man wearing silk robes, 5th-3rd centuries BC, Warring States period, Arthur M. Sackler Museum

The Warring States period was an era of warfare in ancient China, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation; the major states, ruling over large territories, quickly sought to consolidate their powers, leading to the final erosion of the Zhou court's prestige. As a sign of this shift, the rulers of all the major states (except for Chu, which had claimed kingly title much earlier) abandoned their former feudal titles for the title of 王, or King, claiming equality with the rulers of the Zhou.

At the same time, the constant conflict and need for innovative social and political models led to the development of many philosophical doctrines, later known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. The most notable schools of thought include Mohism, expounded by Mozi; Confucianism, represented by Mencius and Xunzi, and Legalism, represented by Shang Yang, Shen Buhai, Shen Dao and Han Fei, and Taoism, represented by Zhuangzhi and Lao Tzu.

The many states that were competing between each other attempted to display their power not only militarily but in their courts and state philosophy. Many differing rulers adopted the differing philosophies in their own advantage or that of their kingdom.

Mencius attempted to instate Confucianism as a state philosophy through proposing that through the governing of moral principles like benevolence and righteousness, the state would win popular support from one state and those neighboring, eliminating the need of a war altogether. Mencius had attempted to convince King Hui of Liang, although was unsuccessful since the king saw no advantage in the period of wars.[16]

Mohism was developed by Mozi (468–376 BC) and it provided a unified moral and political philosophy based on impartiality and benevolence.[17] Mohists had the belief that people change depending on environments around. The same was applied to rulers, which is why one must be cautious of foreign influences. Mozi was very much against warfare, although he was a great tactician in defense. He defended the small state of Song from many attempts of the Chu state.[18]

Taoism was advocated by Laozi, and believed that human nature was good and can achieve perfection by returning to original state. It believed that like a baby, humans are simple and innocent although with development of civilizations it lost its innocence only to be replaced by fraud and greed. Contrarily to other schools, it did not want to gain influence in the offices of states and Laozi even refused to be in the minister of the state of Chu.[18]

Legalism created by Shang Yang in 338 BC, rejected all notions of religion and practices, and believed a nation should be governed by strict law. Not only were severe punishments applied, but they would be grouped with the families and made mutually responsible for criminal act. It proposed radical reforms, and established a society based on solid ranks. Peasants were encouraged to practice agriculture as occupation, and military performance was rewarded. Laws were also applied to all ranks with no exception; even the king was not above punishment. The philosophy was adapted by the Qin state and it created it into a well-organized, centralized state with a bureaucracy chosen on the basis of merit.[16]

This period is most famous for the establishment of complex bureaucracies and centralized governments, as well as a clearly established legal system. The developments in political and military organization were the basis of the power of the Qin state, which conquered the other states and unified them under the Qin Empire in 221 BC.

Nobles, bureaucrats and reformers

The phenomenon of intensive warfare, based on mass formations of infantry rather than the traditional chariots, was one major trend which led to the creation of strong central bureaucracies in each of the major states. At the same time, the process of secondary feudalism which permeated the Spring and Autumn period, and led to such events as the partition of Jin and the usurpation of Qi by the Tian clan, was eventually reversed by the same process of bureaucratisation.

The reforms of Shang Yang in Qin, and of Wu Qi in Chu, both centred on increased centralisation, the suppression of the nobility, and a vastly increased scope of government based on Legalist ideals, which were necessary to mobilise the large armies of the period.[citation needed]

Sophisticated arithmetic

The Tsinghua Bamboo Slips, containing the world's earliest decimal multiplication table, dated 305 BC

A bundle of 21 bamboo slips from the Tsinghua collection dated to 305 BC are the worlds' earliest example of a two digit decimal multiplication table, indicating that sophisticated commercial arithmetic was already established during this period.[19]

Rod numerals were used to represent both negative and positive integers, and rational numbers, a true positional number system, with a blank for zero[20] dating back to the Warring States period.

Literature

An important literary achievement of the Warring States period is the Zuo Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals, which summarizes the preceding Spring and Autumn period. The less famous work Guoyu is thought to be by the same author.

Many sayings of Spring and Autumn philosophers, which had previously been circulated orally, were put into writing in the Warring States. These include the Analects and The Art of War.

Economic developments

The Warring States period saw the proliferation of iron working in China, replacing bronze as the dominant type of metal used in warfare. Areas such as Shu (present-day Sichuan) and Yue (present-day Zhejiang) were also brought into the Chinese cultural sphere during this time. Trade also became important, and some merchants had considerable power in politics, the most prominent of which was Lü Buwei, who rose to become Chancellor of Qin and was a key supporter of the eventual Qin Shihuang.[citation needed]

At the same time, the increased resources of consolidated, bureaucratic states, coupled with the logistical needs of mass levies and large-scale warfare, led to the proliferation of economic projects such as large-scale waterworks. Major examples of such waterworks include the Dujiangyan Irrigation System, which controlled the Min River in Sichuan and turned the former backwater region into a major Qin logistical base, and the Zhengguo Canal which irrigated large areas of land in the Guanzhong Plain, again increasing Qin's agricultural output.

See also

Sengoku period - A period in Japanese history named after this period- Three Kingdoms

References

Citations

^ Cartwright, M. (2017, July 12). Warring States Period. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.ancient.eu/Warring_States_Period/

^ S. Cook, “San De” and Warring States Views on Heavenly Retribution. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 37. (2010) pp. 101–123

^ abcd Shi Ji, chapter 15

^ abc Shi Ji, chapter 46

^ Shi Ji, chapter 16

^ abcde Shi Ji, chapter 4

^ ab Shi Ji, chapter 5

^ ab Shi Ji, chapter 69

^ ”MDBG”, Sökord: 战国策

^ abc Cotterell (2010), pp. 90–91.

^ Lewis (1999), pp. 626–629.

^ Michael Loewe and Edward L. Shaughnessy, The Cambridge History of Ancient China,1999,page 625

^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. ?[page needed]

^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 29.

^ Tzu & Griffith (1963), p. v.

^ ab Stephen G. Haw. “A traveller’s history of China. Interlink Books”. (Canada 2008) Library of Congress. pp. 64–71

^ Fraser, Chris (1 January 2015). "Mohism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 17 March 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Lu & Ke (2012).

^ Nature The 2,300-year-old matrix is the world's oldest decimal multiplication table

^ Unicodes 1D360—1D37F : Counting Rod Numerals

Sources

Cotterell, Arthur (2010), Asia, a Concise History, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-82959-2.

Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Company, ISBN 0-618-13386-0.

Lewis, Mark Edward (1999), "Warring States Political History", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L., The Cambridge history of ancient China: from the origins of civilization to 221 B.C., Cambridge University Press, pp. 587–649, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

Lu, Liqing; Ke, Jinhua (2012), "A Concise History of Chinese Psychology of Religion", Pastoral Psychology, 61 (5–6): 623–639, doi:10.1007/s11089-011-0395-y.

Tzu, Sun; Griffith, Samuel B. (1963), The Art of War, New York: Oxford University Press

Further reading

Li Xueqin. Eastern Zhou and Qin Civilizations. Trans. K.C. Chang. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

ISBN 0-300-03286-2.- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). Wars With The Xiongnu, A Translation from Zizhi tongjian. AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Indiana, U.S.A.

ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4.

Zizhi tongjian, Warring States and Qin by Sima Guang, Volume 1 to 8 - 403-207 BCE. Trans.Joseph P. Yap CreateSpace, 2016.

ISBN 978-1533086938. LCCN: 2016908788.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Warring States Period. |

- Warring States Period - Ancient History Encyclopedia

Warring States Project, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Rulers of the warring states – Chinese Text Project

China's Warring States Period, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Chris Cullen, Vivienne Lo & Carol Michaelson (In Our Time, Apr. 1, 2004)