Names of China

| Part of a series on |

| Names of China |

|---|

|

The names of China include the many contemporary and historical appellations given in various languages for the East Asian country known as Zhōngguó (中國/中国) in its official language. China, the name in English for the country, was derived from Portuguese in the 16th century, and became popular in the mid 19th century.[1] It is believed to be a borrowing from Middle Persian, and some have traced it further back to Sanskrit. It is also generally thought that the ultimate source of the name China is the Chinese word "Qin" (Chinese: 秦), the name of the dynasty that unified China but also existed as a state for many centuries prior. There are however other alternative suggestions for the origin of the word.

Chinese names for China, aside from Zhongguo, include Zhōnghuá (中華/中华), Huáxià (華夏/华夏), Shénzhōu (神州) and Jiǔzhōu (九州). Hàn (漢/汉) and Táng (唐) are common names given for the Chinese ethnicity. The People's Republic of China (Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó) and Republic of China (Zhōnghuá Mínguó) are the official names for the two contemporary sovereign states currently claiming sovereignty over the traditional area of China. "Mainland China" is used to refer to areas under the jurisdiction by the PRC usually excluding Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.

There are also names for China that are derived from the languages of other ethnic groups other than the Han; examples include "Cathay" from the Khitan language and "Tabgach" from Tuoba.

| Zhongguo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

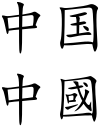

"China" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 中國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōngguó | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Middle or Central State[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhonghua | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōnghuá | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | .mw-parser-output .uchen{font-family:"Qomolangma-Dunhuang","Qomolangma-Uchen Sarchen","Qomolangma-Uchen Sarchung","Qomolangma-Uchen Suring","Qomolangma-Uchen Sutung","Qomolangma-Title","Qomolangma-Subtitle","Qomolangma-Woodblock","DDC Uchen","DDC Rinzin",Kailash,"BabelStone Tibetan",Jomolhari,"TCRC Youtso Unicode","Tibetan Machine Uni",Wangdi29,"Noto Sans Tibetan","Microsoft Himalaya"}.mw-parser-output .ume{font-family:"Qomolangma-Betsu","Qomolangma-Chuyig","Qomolangma-Drutsa","Qomolangma-Edict","Qomolangma-Tsumachu","Qomolangma-Tsuring","Qomolangma-Tsutong","TibetanSambhotaYigchung","TibetanTsugRing","TibetanYigchung"} ཀྲུང་གོ་ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cungguek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | .mw-parser-output .font-ugy{font-family:"UKIJ Tuz","UKIJ Nasq","UKIJ Basma","UKIJ_Mac Basma","UKIJ Zilwa","UKIJ Esliye","UKIJ Tuz Basma","UKIJ Tuz Kitab","UKIJ Tuz Gezit","UKIJ Tuz Qara","UKIJ Tuz Qara","UKIJ Tuz Tor","UKIJ Kesme","UKIJ Kesme Tuz","UKIJ Qara","UKIJ Basma Aq","UKIJ Basma Qara","UKIJ Basma Tuz","UKIJ Putuk","UKIJ Tuz Xet","UKIJ Tom Xet","UKIJ Tuz Jurnal","UKIJ Arabic","UKIJ CJK","UKIJ Ekran","UKIJ_Mac Ekran","UKIJ Teng","UKIJ Tor","UKIJ Tuz Tom","UKIJ Mono Keng","UKIJ Mono Tar","UKIJ Nokia","UKIJ SimSun","UKIJ Yanfon","UKIJ Qolyazma","UKIJ Saet","UKIJ Nasq Zilwa","UKIJ Sulus","UKIJ Sulus Tom","UKIJ 3D","UKIJ Diwani","UKIJ Diwani Yantu","UKIJ Diwani Tom","UKIJ Esliye Tom","UKIJ Esliye Qara","UKIJ Jelliy","UKIJ Kufi","UKIJ Kufi Tar","UKIJ Kufi Uz","UKIJ Kufi Yay","UKIJ Merdane","UKIJ Ruqi","UKIJ Mejnuntal","UKIJ Junun","UKIJ Moy Qelem","UKIJ Chiwer Kesme","UKIJ Orxun-Yensey","UKIJ Elipbe","UKIJ Qolyazma Tez","UKIJ Qolyazma Tuz","UKIJ Qolyazma Yantu","UKIJ Ruqi Tuz",FZWWBBOT_Unicode,FZWWHQHTOT_Unicode,Scheherazade,Lateef,LateefGR,"Noto Naskh Arabic","Microsoft Uighur";font-feature-settings:"cv50"1} جۇڭگو | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | .mw-parser-output .font-mong{font-family:"Menk Hawang Tig","Menk Qagan Tig","Menk Garqag Tig","Menk Har_a Tig","Menk Scnin Tig","Oyun Gurban Ulus Tig","Oyun Qagan Tig","Oyun Garqag Tig","Oyun Har_a Tig","Oyun Scnin Tig","Oyun Agula Tig","Mongolian Baiti","Noto Sans Mongolian","Mongolian Universal White","Mongol Usug","Mongolian White","MongolianScript","Code2000","Menksoft Qagan"}.mw-parser-output .font-mong-mnc,.mw-parser-output .font-mong:lang(mnc-Mong),.mw-parser-output .font-mong:lang(dta-Mong),.mw-parser-output .font-mong:lang(sjo-Mong){font-family:"Abkai Xanyan","Abkai Xanyan LA","Abkai Xanyan VT","Abkai Xanyan XX","Abkai Xanyan SC","Abkai Buleku","Daicing White","Mongolian Baiti","Noto Sans Mongolian","Mongolian Universal White"} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai Gurun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contents

1 Sinitic names

1.1 Zhongguo

1.1.1 Pre-Qing

1.1.2 Qing

1.1.3 Middle Kingdom

1.2 Huaxia

1.3 Tianxia and Tianchao

1.4 Jiangshan

1.5 Jiuzhou

1.6 Shenzhou

1.7 Sihai

1.8 Han

1.9 Tang

1.10 Dalu and Neidi

2 Official names

2.1 People's Republic of China

2.2 Republic of China

3 Names in non-Chinese records

3.1 Chin, China

3.1.1 List of derived terms

3.2 Seres, Ser, Serica

3.3 Sinae, Sin

3.4 Cathay

3.5 Tabgach

3.6 Nikan

3.7 Kara

3.8 Morokoshi

3.9 Mangi

4 See also

5 References

5.1 Citations

5.2 Sources

Sinitic names

Zhongguo

Pre-Qing

Zhōngguó is the most common sinitic name for China in modern times. The first appearance of the characters "中國" on an artifact was in the Western Zhou on a ritual vessel known as He zun.[3] It is formed by combining the characters zhōng (中) meaning "central" or "middle", and guó (國/国), representing "state" or "states"; in contemporary usage, "nation". Prior to the Qin unification of China, "Zhongguo" referred to the "Central States"; the connotation was the primacy of a culturally distinct core area, centered on the Yellow River valley, as distinguished from the tribal periphery.[4]

The brocade arm protector with the words "Five stars rise in the east, benefitting Zhongguo (中國) ", made in the Han dynasty.

In later periods, however, "Zhongguo" was not used in this sense. Dynastic names were used for the state in Imperial China and concepts of the state aside from the ruling dynasty were little understood.[1] Rather, the country was called by the name of the dynasty, such as "Han dynasty" (漢朝; Hàncháo), "Tang dynasty" (唐朝; Tángcháo), "The Great Ming" (大明; Dàmíng), "The Great Qing" (大清; Dàqīng), as the case might be. but the most traditional name that China has used to refer to itself is “Zhonggou". Missionaries Matteo Ricci and John Livingston Nevius preached in China in different dynasties. In their Record, Chinese people often called themselves "Chung kwoh"; the word meaning "middle kingdom". ("中國"'s transcription in the formerly common Wade–Giles romanization scheme is Chung1-Kuo4, reflecting the phonetic realization as [ʈ͡ʂʊŋ⁵⁵ ku̯ɔ³⁵] in Standard Mandarin.)

Zhōngguó is a very common word in both writing and speaking,[5][6] and may be used with the name of the dynasty. Many case studies have proved that there were times China called itself “Zhongguo” in Chinese history and historical sites. Until the 19th century when the international system came to require a common legal language, there was no need for a fixed or unique name.[7]

The Nestorian Stele大秦景教流行中國碑 entitled"Stele to the propagation in Zhongguo (中國) of the luminous religion of Daqin (Roman)", was erected in China in 781.

There were different usages of the term "Zhongguo" in every period. It could refer to the capital of the emperor to distinguish it from the capitals of his vassals, as in Western Zhou. It could refer to the states of the Central Plain to distinguish them from states in outer regions. During the Han dynasty, three usages of "Zhongguo" were common. The Shi Jing explicitly defines "Zhongguo" as the capital; the Records of the Grand Historian uses the concept zhong to indicate the center of civilization: "Eight famous mountains are there in Tianxia. Three are in Man and Yi. Five are in Zhōnghuá." The Records of the Three Kingdoms uses the concept of the central states in "Zhōnghuá", or the states in "Zhōnghuá" which is the center, depending on the interpretation. It records the following exhortation: "If we can lead the host of Wu and Yue to oppose "Zhongguo," then let us break off relations with them soon." In this sense, the term "Zhongguo" is synonymous with Zhōnghuá (中華/中华) and Huáxià (華夏/华夏), names for China that comes from the Xia dynasty.

From the Qin to Ming dynasty literati discussed "Zhongguo" as both a historical place or territory and as a culture. Writers of the Ming period in particular used the term as a political tool to express opposition to expansionist policies that incorporated foreigners into the empire.[8] In contrast foreign conquerors typically avoided discussions of "Zhongguo" and instead defined membership in their empires to include both Han and non-Han peoples.[9]

Qing

Zhongguo appeared in a formal international legal document for the first time during the Qing dynasty in the Treaty of Nerchinsk, 1689. The term was then used in communications with other states and in treaties. The Manchu rulers incorporated Inner Asian polities into their empire, and Wei Yuan, a statecraft scholar, distinguished the new territories from Zhongguo, which he defined as the 17 provinces of "China proper" plus the Manchu homelands in the Northeast. By the late 19th century the term had emerged as a common name for the whole country. The empire was sometimes referred to as Great Qing but increasingly as Zhongguo (see the discussion below).[10]

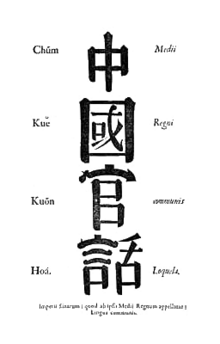

"Middle Kingdom's Common Speech" (Medii Regni Communis Loquela, Zhongguo Guanhua, 中國官話), the frontispiece of an early Chinese grammar published by Étienne Fourmont in 1742[11]

Dulimbai Gurun is the Manchu name for China.[12][13][14] The historian Zhao Gang writes that "not long after the collapse of the Ming, China [Zhongguo] became the equivalent of Great Qing (Da Qing)—another official title of the Qing state", and "Qing and China became interchangeable official titles, and the latter often appeared as a substitute for the former in official documents."[15] The Qing dynasty referred to their realm as "Dulimbai Gurun" in Manchu. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing realm (including present day Manchuria, Xinjiang, Mongolia, Tibet and other areas as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state, rejecting the idea that China only meant Han areas; both Han and non-Han peoples were part of "China". Officials used "China" (though not exclusively) in official documents, international treaties, and foreign affairs, and the "Chinese language" (Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i bithe) referred to Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol languages, and the term "Chinese people" (中國人; Zhōngguórén; Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) referred to all Han, Manchus, and Mongol subjects of the Qing.[16] Ming loyalist Han literati held to defining the old Ming borders as China and using "foreigner" to describe minorities under Qing rule such as the Mongols, as part of their anti-Qing ideology.[17]

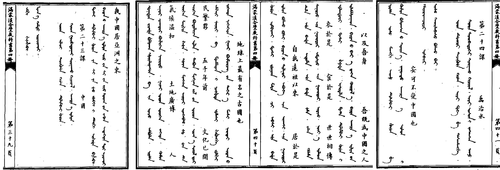

Chapter China (中國) of "The Manchurian, Mongolian and Han Chinese Trilingual Textbook" (滿蒙漢三語合璧教科書) published in Qing dynasty: "Our country China is located in East Asia... For 5000 years, culture flourished (in the land of China)... Since we are Chinese, how can we not love China."

When the Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land was absorbed into Dulimbai Gurun in a Manchu language memorial.[18][19][20] The Qing expounded on their ideology that they were bringing together the "outer" non-Han Chinese like the Inner Mongols, Eastern Mongols, Oirat Mongols, and Tibetans together with the "inner" Han Chinese, into "one family" united in the Qing state, showing that the diverse subjects of the Qing were all part of one family, the Qing used the phrase "Zhōngwài yījiā" (中外一家; "China and other [countries] as one family") or "Nèiwài yījiā" (內外一家; "Interior and exterior as one family"), to convey this idea of "unification" of the different peoples.[21] A Manchu language version of a treaty with the Russian Empire concerning criminal jurisdiction over bandits called people from the Qing as "people of the Central Kingdom (Dulimbai Gurun)".[22][23][24][25] In the Manchu official Tulisen's Manchu language account of his meeting with the Torghut Mongol leader Ayuki Khan, it was mentioned that while the Torghuts were unlike the Russians, the "people of the Central Kingdom" (dulimba-i gurun/中國; Zhōngguó) were like the Torghut Mongols, and the "people of the Central Kingdom" referred to the Manchus.[26]

Mark Elliott noted that it was under the Qing that "China" transformed into a definition of referring to lands where the "state claimed sovereignty" rather than only the Central Plains area and its people by the end of the 18th century.[27]

Elena Barabantseva also noted that the Manchu referred to all subjects of the Qing empire regardless of ethnicity as "Chinese" (中國之人; Zhōngguó zhīrén; "China's person"), and used the term (中國; Zhōngguó) as a synonym for the entire Qing empire while using "Hàn rén" (漢人) to refer only to the core area of the empire, with the entire empire viewed as multiethnic.[28]

Joseph W. Esherick noted that while the Qing Emperors governed frontier non-Han areas in a different, separate system under the Lifanyuan and kept them separate from Han areas and administration, it was the Manchu Qing Emperors who expanded the definition of Zhongguo (中國) and made it "flexible" by using that term to refer to the entire Empire and using that term to other countries in diplomatic correspondence, while some Han Chinese subjects criticized their usage of the term and the Han literati Wei Yuan used Zhongguo only to refer to the seventeen provinces of China and three provinces of the east (Manchuria), excluding other frontier areas.[29] Due to Qing using treaties clarifying the international borders of the Qing state, it was able to inculcate in the Chinese people a sense that China included areas such as Mongolia and Tibet due to education reforms in geography which made it clear where the borders of the Qing state were even if they didn't understand how the Chinese identity included Tibetans and Mongolians or understand what the connotations of being Chinese were.[30] The Treaty of Nanking (1842) English version refers to "His Majesty the Emperor of China" while the Chinese refers both to "The Great Qing Emperor" (Da Qing Huangdi) and to Zhongguo as well. The Treaty of Tientsin (1858) has similar language.[7]

In the late 19th century the reformer Liang Qichao argued in a famous passage that "our greatest shame is that our country has no name. The names that people ordinarily think of, such as Xia, Han, or Tang, are all the titles of bygone dynasties." He argued that the other countries of the world "all boast of their own state names, such as England and France, the only exception being the Central States." [31] The Japanese term "Shina" was proposed as a basically neutral Western-influenced equivalent for "China". Liang and Chinese revolutionaries, such as Sun Yat-sen, who both lived extensive periods in Japan, used Shina extensively, and it was used in literature as well as by ordinary Chinese. But with the overthrow of the Qing in 1911, most Chinese dropped Shina as foreign and demanded that even Japanese replace it with Zhonghua minguo or simply Zhongguo.[32] Liang went on to argue that the concept of tianxia had to be abandoned in favor of guojia, that is, "nation," for which he accepted the term Zhongguo.[33] After the founding of the Chinese Republic in 1912, Zhongguo was also adopted as the abbreviation of Zhonghua minguo.[34]

Qing official Zhang Deyi objected to the western European name "China" and said that China referred to itself as Zhonghua in response to a European who asked why Chinese used the term guizi to refer to all Europeans.[35]

In the 20th century after the May Fourth Movement, educated students began to spread the concept of Zhōnghuá (中華/中华), which represented the people, including 56 minority ethnic groups and the Han Chinese, with a single culture identifying themselves as "Chinese". The Republic of China and the People's Republic of China both used the title "Zhōnghuá" in their official names. Thus, "Zhōngguó" became the common name for both governments. Overseas Chinese are referred to as huáqiáo (華僑/华侨), literally "Chinese overseas", or huáyì (華裔/华裔), literally "Chinese descendant" (i.e., Chinese children born overseas).

Middle Kingdom

The English translation of "Zhongguo" as the "Middle Kingdom" entered European languages through the Portuguese in the 16th century and became popular in the mid 19th century. By the mid 20th century the term was thoroughly entrenched in the English language to reflect the Western view of China as the inwards looking Middle Kingdom, or more accurately the Central Kingdom. Endymion Wilkinson points out that the Chinese were not unique in thinking of their country as central, although China was the only culture to use the concept for their name.[36] The term Zhongguo was also not commonly used as a name for China until quite recently, nor did it mean the "Middle Kingdom" to the Chinese, or even have the same meaning throughout the course of history.[37]

- "Zhōngguó" in different languages (see also section on its translation Middle Kingdom)

Burmese: Alaï-praï-daï

Catalan: País del Centre (literally: The Middle's Country/State)

Czech: Říše středu (literally: "The Empire of the Center")

Dutch: Middenrijk (literally: "Middle Empire" or "Middle Realm")

English: Middle Kingdom, Central Kingdom

Finnish: Keskustan valtakunta (literally: "The State of the Center")

French: Empire du milieu (literally: "Middle Empire") or Royaume du milieu (literally: "Middle Kingdom")

German: Reich der Mitte (literally: "Middle Empire")

Greek: Mesí aftokratoría| Μέση αυτοκρατορία (literally: "Middle Empire") or Kentrikí aftokratoría| Κεντρική αυτοκρατορία (literally: "Central Empire")

Hmong: Suav Teb, Roob Kuj, Tuam Tshoj, 中國 (literally: "Land of the Xia, The Middle Kingdom, Great Qing")

Hungarian: Középső birodalom (literally: "Middle Empire")

Indonesian: Tiongkok (from Tiong-kok, the Hokkien name for China)[38]

Italian: Impero di Mezzo (literally: "Middle Empire")

Japanese: Chūgoku (中国; ちゅうごく)

Kazakh: Juñgo (جۇڭگو)

Korean: Jungguk (중국; 中國)

Li: Dongxgok

Manchu:

ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (Dulimbai gurun) or

ᠵᡠᠨᡤᠣ (Jungg'o) (They were the official names for "China" in Manchu language)

Mongolian:

ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ (Dumdadu ulus) (the official name for "China" used in Inner Mongolia)

Polish: Państwo Środka (literally: "The State of the Center")

Portuguese: Império do Meio (literally: "Middle Empire")

Russian: Срединное Царство (Sredínnoye Tsárstvo; literally: "Middle Empire")

Spanish: País del Centro (literally: The Middle's Country/State)

Swedish: Mittens rike (literally: The Middle's Kingdom/Empire/Realm/State)

Tibetan: Krung-go (

ཀྲུང་གོ་)

Uyghur:

جۇڭگو, ULY: Junggo

Vietnamese: Trung Quốc (中國)

Yi: ꍏꇩ (/tʂõ˧ ko˨˩/ or /tʂõ˧ kwɛ˨˩/)

Zhuang: Cunghgoz (older orthography: Cuŋƅgoƨ)

- "Zhōnghuá" in different languages

Indonesian: Tionghoa (from Tiong-hôa, the Hokkien counterpart)

Japanese: Chūka (中華; ちゅうか)

Korean: Junghwa (중화; 中華)

Kazakh: Juñxwa (جۇڭحوا)

Li: Dongxhwax

Manchu:

ᠵᡠᠩᡥᡡᠸᠠ (Junghūwa)

Zhuang: Cunghvaz (Old orthography: Cuŋƅvaƨ)

Tibetan:

ཀྲུང་ཧྭ (krung hwa)

Uyghur:

جۇڭخۇا, ULY: Jungxua

Vietnamese: Trung hoa (中華)

Yi: ꍏꉸ (/tʂõ˧ xɔ˨˩/ or /tʂõ˧ xwa˨˩/)

Huaxia

The name Huaxia (華夏/华夏; pinyin: huáxià), generally used as a sobriquet in Chinese text, is the combination of two words:

Hua which means "flowery beauty" (i.e. having beauty of dress and personal adornment 有服章之美,謂之華).

Xia which means greatness or grandeur (i.e. having greatness of social customs/courtesy/polite manners and rites/ceremony 有禮儀之大,故稱夏).[39]

These two terms originally referred to the elegance of the traditional attire of the Han Chinese (漢服 Hànfú, or simply 衣冠 yīguān, literally clothes and headgear) and the Confucian concept of rituals (禮/礼 lǐ).[citation needed] In the original sense, Huaxia refers to a confederation of tribes—living along the Yellow River—who were the ancestors of what later became the Han ethnic group in China.[citation needed] During the Warring States (475–221 BCE), the self-awareness of the Huaxia identity developed and took hold in ancient China.

Tianxia and Tianchao

Tianxia (天下; pinyin: Tiānxià) literally means "under heaven"; and Tianchao (天朝) means "Heavenly Dynasty". These terms were usually used in the context of civil wars or periods of division, in which whoever ends up reunifying China is said to have ruled Tianxia, or everything under heaven. This fits with the traditional Chinese theory of rulership in which the emperor was nominally the political leader of the entire world and not merely the leader of a nation-state within the world. Historically the term was connected to the later Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE), especially the Spring and Autumn period (eighth to fourth century BCE) and the Warring States period (from there to 221 BCE, when China was reunified by the Qin state).

Russian: Поднебесная (Podnebésnaya; lit. "under the heaven")

Jiangshan

Jiangshan (江山; pinyin: Jiāngshān) literally means "Rivers and mountains". This term is quite similar in usage to Tianxia, and simply refers to the entire world, and here the most prominent features of which being rivers and mountains. Use of this term is also common as part of the phrase "designing rivers and mountains" meaning maintaining and improving government and policy in the world.

Jiuzhou

The name Jiuzhou (九州; pinyin: jiǔ zhōu) means "nine provinces". Widely used in pre-modern Chinese text, the word originated during the middle of Warring States period of China (c. 400–221 BCE). During that time, the Yellow River river region was divided into nine geographical regions; thus this name was coined. Some people also attribute this word to the mythical hero and king, Yu the Great, who, in the legend, divided China into nine provinces during his reign. (Consult Zhou for more information.)

Shenzhou

This name means Divine Land (神州; pinyin: Shénzhōu; literally: "nine provinces") and comes from the same period as Jiuzhou. It was thought that the world was divided into nine major states, one of which is Shenzhou, which is in turn divided into nine smaller states, one of which is Jiuzhou mentioned above.

Sihai

This name, Four Seas (四海; pinyin: sìhǎi), is sometimes used to refer to the world, or simply China, which is perceived as the civilized world. It came from the ancient notion that the world is flat and surrounded by sea.

Han

| Han | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hàn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | hán | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 한 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | かん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name Han (漢/汉; pinyin: Hàn) derives from the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), who presided over China's first "golden age". The Han dynasty collapsed in 220 and was followed by a long period of disorder, including Three Kingdoms, Sixteen Kingdoms, and Southern and Northern Dynasties periods. During these periods, various non-Chinese ethnic groups invaded from the north and conquered areas of North China, which they held for several centuries. It was during this period that people began to use the term "Han" to refer to the natives of North China, who (unlike the invaders) were the descendants of the subjects of the Han dynasty.

During the Yuan dynasty Mongolian rulers divided people into four classes: Mongols, Semu or "Colour-eyeds", Hans, and "Southerns". Northern Chinese were called Han, which was considered to be the highest class of Chinese. This class "Han" includes all ethnic groups in northern China including Khitan and Jurchen who have in most part sinicized during the last two hundreds years. The name "Han" became popularly accepted.

During the Qing dynasty, the Manchu rulers also used the name Han to distinguish the local Chinese from the Manchus. After the fall of the Qing government, the Han became the name of a nationality within China. Today the term "Han Persons", often rendered in English as Han Chinese, is used by the People's Republic of China to refer to the most populous of the 56 officially recognized ethnic groups of China. The "Han Chinese" are simply referred to as "Chinese" by some.

Tang

| Tang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Táng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | đường | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 당 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | とう (On), から (Kun) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name Tang (唐; pinyin: Táng) comes from the Tang Dynasty (618–907) that presided over China's second golden age. It was during the Tang Dynasty that South China was finally and fully Sinicized; Tang would become synonymous with China in Southern China and it is usually Southern Chinese who refer to themselves as "Tang ren" (唐人, pinyin: Tángrén; literally: "People of Tang").[40] For example, the sinicization and rapid development of Guangdong during the Tang period would lead the Cantonese to refer to themselves as Tong-yan (唐人) in Cantonese, while China is called Tong-saan (唐山; pinyin: Tángshān; literally: "Tang Mountain").[41]Chinatowns worldwide, often dominated by Southern Chinese, also became referred to Tong-yan-gaai (唐人街; pinyin: Tángrénjiē; literally: "Tang people street"). The Cantonese term is recorded as Tongsan in Old Malay as one of the local terms for China, along with the Sanskrit-derived Cina. It is still used in Malaysia today, usually in a derogatory sense.

Among Taiwanese, Tn̂g-soaⁿ has been used, for example, in the saying, "has Tangshan father, no Tangshan mother" (有唐山公,無唐山媽; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ū Tn̂g-soaⁿ kong, bô Tn̂g-soaⁿ má).[42][43] This refers how the Han people crossing the Taiwan Strait in the 17th and 18th centuries were mostly men, and that many of their offspring would be through intermarriage with Taiwanese aborigine women.

In Ryukyuan, Karate was originally called tii (手, hand) or karatii (唐手, Tang hand) because 唐ぬ國 too-nu-kuku or kara-nu-kuku (唐ぬ國) was a common Ryukyuan name for China; it was changed to karate (空手, open hand) to appeal to Japanese people after the First Sino-Japanese War.

Dalu and Neidi

Dàlù (大陸/大陆; pinyin: dàlù), literally "big continent" or "mainland" in this context, is used as a short form of Zhōnggúo Dàlù (中國大陸/中国大陆, Mainland China), excluding (depending on the context) Hong Kong and Macau, and/or Taiwan. This term is used in official context in both the mainland and Taiwan, when referring to the mainland as opposed to Taiwan. In certain contexts, it is equivalent to the term Neidi (内地; pinyin: nèidì, literally "the inner land"). While Neidi generally refers to the interior as opposed to a particular coastal or border location, or the coastal or border regions generally, it is used in Hong Kong specifically to mean mainland China excluding Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. Increasingly, it is also being used in an official context within mainland China, for example in reference to the separate judicial and customs jurisdictions of mainland China on the one hand and Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan on the other.

The term Neidi is also often used in Xinjiang and Tibet to distinguish the eastern provinces of China from the minority-populated, autonomous regions of the west.

Official names

People's Republic of China

| People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

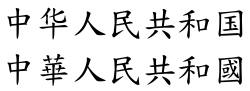

"People's Republic of China" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中华人民共和国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華人民共和國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Cộng hòa Nhân dân Trung Hoa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 共和人民中華 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghvaz Yinzminz Gunghozgoz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 중화인민공화국 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 中華人民共和國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 中華人民共和国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ちゅうかじんみんきょうわこく | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭخۇا خەلق جۇمھۇرىيىتى | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (ᡩᡡᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai niyalmairgen gungheg' gurun(Dulimbai Gurun) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name New China has been frequently applied to China by the Communist Party of China as a positive political and social term contrasting pre-1949 China (the establishment of the PRC) and the new socialist state, which eventually became Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó (see below), known in English as the "People's Republic of China". This term is also sometimes used by writers outside mainland China. The PRC was known to many in the West during the Cold War as "Communist China" or "Red China" to distinguish it from the Republic of China which is commonly called "Taiwan", "Nationalist China" or "Free China". In some contexts, particularly in economics, trade, and sports, "China" is often used to refer to mainland China to the exclusion of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

The official name of the People's Republic of China in various official languages and scripts:

Simplified Chinese: 中华人民共和国 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó) – Official language and script, used in mainland China, Singapore and Malaysia

Traditional Chinese: 中華人民共和國 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó; Jyutping: Zung1waa4 Jan4man4 Gung6wo4gwok3) – Official script in Hong Kong, Macau, and common used in Taiwan (ROC).- English: People's Republic of China – Official in Hong Kong

Kazakh: As used within Republic of Kazakhstan, Қытай Халық Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Qıtay Xalıq Respwblïkası (in Latin script), قىتاي حالىق رەسپۋبلىيكاسى (in Arabic script); as used within the People's Republic of China, جۇڭحۋا حالىق رەسپۋبليكاسى (in Arabic script), Жұңxуа Халық Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Juñxwa Xalıq Respwblïkası (in Latin script) . The Cyrillic script is the predominant script in the Republic of Kazakhstan, while the Arabic script is normally used for the Kazakh language in the People's Republic of China.

Korean: 중화 인민 공화국 (中華人民共和國; Junghwa Inmin Gonghwaguk) – Used in Yanbian Prefecture (Jilin) and Changbai County (Liaoning)

Manchurian:

ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (Dulimbai niyalmairgen gunghe' gurun) or

ᠵᡠᠩᡥᡡᠸᠠ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝᡬᠣ (Junghūwa niyalmairgen gungheg'o)

Mongolian:

ᠪᠦᠭᠦᠳᠡ ᠨᠠᠶᠢᠷᠠᠮᠳᠠᠬᠤ ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ (Bügüde nayiramdaqu dumdadu arad ulus) – Official in Inner Mongolia; Бүгд Найрамдах Хятад Ард Улс (Bügd Nairamdakh Khyatad Ard Uls) – used in Mongolia

Portuguese: República Popular da China – Official in Macau

Tibetan:

ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ, Wylie: krung hwa mi dmangs spyi mthun rgyal khab, ZYPY: 'Zhunghua Mimang Jitun Gyalkab' – Official in PRC's Tibet

Tibetan:

རྒྱ་ནག་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ, Wylie: rgya nag mi dmangs spyi mthun rgyal khab – Official in Tibet Government-in-Exile

Uyghur:

جۇڭخۇا خەلق جۇمھۇرىيىت (Jungxua Xelq Jumhuriyiti) – Official in Xinjiang

Yi: ꍏꉸꏓꂱꇭꉼꇩ (Zho huop rep mip gop hop guop) – Official in Liangshan (Sichuan) and several Yi-designated autonomous counties

Zaiwa: Zhunghua Mingbyu Muhum Mingdan – Official in Dehong (Yunnan)

Zhuang: Cunghvaz Yinzminz Gunghozgoz (Old orthography: Cuŋƅvaƨ Yinƨminƨ Guŋƅoƨ) – Official in Guangxi

Republic of China

| Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Republic of China" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chunghwa Minkuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese Taipei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華臺北 or 中華台北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华台北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺澎金馬 個別關稅領域 or 台澎金馬 個別關稅領域 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台澎金马 个别关税领域 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣 or 台灣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portuguese: (Ilha) Formosa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 福爾摩沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 福尔摩沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | beautiful island | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Trung Hoa Dân Quốc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 중화민국 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 中華民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ちゅうかみんこく | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1912, China adopted its official name, Zhōnghuá Mínguó (see below), known in English as the "Republic of China", which also has sometimes been referred to as "Republican China" or "Republican Era" (民國時代), in contrast to the empire it replaced, or as "Nationalist China", after the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang). 中華 (Zhonghua) is a term that pertains to "China" while 民國 (mínguó), literally "people's country", stands for "republic".[44][45] With the separation from mainland China in 1949 as a result of the Chinese Civil War, the territory of the Republic of China has largely been confined to the island of Taiwan and some other small islands. Thus, the country is often simply referred to as simply "Taiwan", although this may not be perceived as politically neutral. (See Taiwan Independence.) Amid the hostile rhetoric of the Cold War, the government and its supporters sometimes referred to itself as "Free China" or "Liberal China", in contrast to People's Republic of China (which was historically called the "Bandit-occupied Area" (匪區) by the ROC). In addition, the ROC, due to pressure from the PRC, was forced to use the name "Chinese Taipei" (中華台北) whenever it participates in international forums or most sporting events such as the Olympic Games.

The official name of the Republic of China in various official languages and scripts:

- English: Republic of China – Official in Hong Kong, Chinese Taipei – official designation in several international organizations (International Olympic Committee, FIFA, Miss Universe, World Health Organization), Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu – World Trade Organization, Taiwan – Most commonly used

Traditional Chinese: 中華民國 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó; Jyutping: Zung1waa4 Man4gwok3), 中華臺北 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Táiběi), 臺澎金馬個別關稅領域 (pinyin: Tái-Péng-Jīn-Mǎ Gèbié Guānshuì Lǐngyù), 臺灣 (pinyin: Táiwān) – Official script in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan and the islands controlled by the ROC

Simplified Chinese: 中华民国 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó), 中華台北 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Táiběi), 台澎金马个别关税领域 (pinyin: Tái-Péng-Jīn-Mǎ Gèbié Guānshuì Lǐngyù), 台湾 (pinyin: Táiwān) – Official language and script, used in Mainland China, Singapore and Malaysia

Hindi: चीनी गणराज्य (Cīnī Gaṇarājya) – Official in Arunachal Pradesh

Kazakh: As used within Republic of Kazakhstan, Қытай Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Qıtay Respwblïkası (in Latin script), قىتاي رەسپۋبلىيكاسى (in Arabic script); as used within the People's Republic of China, Жұңxуа Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Juñxwa Respwblïkası (in Latin script), جۇڭحۋا رەسپۋبليكاسى (in Arabic script). The Cyrillic script is the predominant script in the Republic of Kazakhstan, while the Arabic script is normally used for the Kazakh language in the People's Republic of China.

Manchurian:

ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ

ᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (Dulimbai irgen' gurun)

Mongolian:

ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ

ᠢᠷᠭᠡᠨ

ᠤᠯᠤᠰ Дундад иргэн улс (Dumdadu irgen ulus) – Official for its history name before 1949 in Inner Mongolia and Mongolia; Бүгд Найрамдах Хятад Улс (Bügd Nairamdakh Khyatad Uls) – used in Mongolia for Roc in Taiwan

Portuguese: República da China – Official in Macau, Formosa – former name

Tibetan:

ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་དམངས་གཙོའི་རྒྱལ་ཁབ།, Wylie: krung hwa dmangs gtso'i rgyal khab, ZYPY: Zhunghua Mang Jitun Gyalkab, Tibetan:

ཐའེ་ཝན།, Wylie: tha'e wan – Official in PRC's Tibet

Tibetan:

རྒྱ་ནག་དམངས་གཙོའི་རྒྱལ་ཁབ, Wylie: rgya nag dmangs gtso'i rgyal khab – Official in Tibet Government-in-Exile

Uyghur:

جۇڭخۇا مىنگو, ULY: Jungxua Mingo – Official in Xinjiang

Zhuang: Cunghvaz Mingoz (Old orthography: Cuŋƅvaƨ Minƨƅoƨ) – Official in Guangxi

Japanese: 中華民国 (ちゅうかみんこく; Chūka Minkoku) – Used in Japan

Korean: 중화민국 (中華民國; Junghwa Minguk) – Used in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture

Names in non-Chinese records

Names used in the rest of Asia, especially East and Southeast Asia, are usually derived directly from words in a language of China. Those languages belonging to a former dependency (tributary) or Chinese-influenced country have an especially similar pronunciation to that of Chinese. Those used in Indo-European languages, however, have indirect names that came via other routes and bear little resemblance to what is used in China.

Chin, China

English, most Indo-European languages, and many others use various forms of the name "China" and the prefix "Sino-" or "Sin-" from the Latin Sina.[46][47] Europeans had knowledge of a country known as Thina or Sina from the early period;[48] the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea from perhaps the first century AD recorded a country known as Thin (θίν).[49] The English name for "China" itself is derived from Middle Persian (Chīnī چین). This modern word "China" was first used by Europeans starting with Portuguese explorers of the 16th century – it was first recorded in 1516 in the journal of the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa.[50][51] The journal was translated and published in England in 1555.[52]

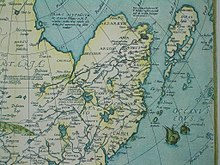

China (referring to today's Guangdong), Mangi (inland of Xanton (Shandong)), and Cataio (located inland of China and Chequan (Zhejiang), and including the capital Cambalu, Xandu, and a marble bridge) are all shown as separate regions on this 1570 map by Abraham Ortelius

The traditional etymology, proposed in the 17th century by Martin Martini and supported by later scholars such as Paul Pelliot and Berthold Laufer, is that the word "China" and its related terms are ultimately derived from the polity known as Qin that unified China to form the Qin Dynasty (秦, Old Chinese: *dzin) in the 3rd century BC, but existed as a state on the furthest west of China since the 9th century BC.[48][53][54] This is still the most commonly held theory, although many other suggestions have also been mooted.[55][56]

The existence of the word Cīna in ancient Hindu texts was noted by the Sanskrit scholar Hermann Jacobi who pointed out its use in the Book 2 of Arthashastra with reference to silk and woven cloth produced by the country of Cīna, although textual analysis suggests that Book 2 may not have been written long before 150 AD.[57] The word is also found in other Sanskrit texts such as the Mahābhārata and the Laws of Manu.[58] The Indologist Patrick Olivelle argued that the word Cīnā may not have been known in India before the first century BC, nevertheless he agreed that it probably referred to Qin but thought that the word itself was derived from a Central Asian language.[59] Some Chinese and Indian scholars argued for the state of Jing (荆, another name for Chu) as the likely origin of the name.[56] Another suggestion, made by Geoff Wade, is that the Cīnāh in Sanskrit texts refers to an ancient kingdom centered in present-day Guizhou, called Yelang, in the south Tibeto-Burman highlands.[58] The inhabitants referred to themselves as Zina according to Wade.[60]

The term "China" can also be used to refer to:

- the modern states known as the People's Republic of China (PRC) and (before the 1970s) the Republic of China (ROC)

- "Mainland China" (中國大陸/中国大陆, Zhōngguó Dàlù in Mandarin), which is the territory of the PRC minus the two special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau;

- "China proper", a term used to refer to the historical heartlands of China without peripheral areas like Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang

In economic contexts, "Greater China" (大中華地區/大中华地区, dà Zhōnghuá dìqū) is intended to be a neutral and non-political way to refer to Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Sinologists usually use "Chinese" in a more restricted sense, akin to the classical usage of Zhongguo, to the Han ethnic group, which makes up the bulk of the population in China and of the overseas Chinese.

Barbuda's 1584 map, also published by Ortelius, already applies the name China to the entire country. However, for another century many European maps continued to show Cathay as well, usually somewhere north of the Great Wall

List of derived terms

Afrikaans: Sjina (pronounced [ˈʃina])

Albanian: Kinë (pronounced [kinə])

Amharic: Chayna (from English)

Armenian: Չինաստան (pronounced [t͡ʃʰinɑsˈtɑn])

Assamese: চীন (pronounced [sin])

Azeri: Çin (IPA: [tʃin])

Basque: Txina (IPA: [ˈtʃinə])

Bangla/Bengali: Cīn (চীন pronounced [ˈtʃiːn])- Catalan: Xina ([ˈʃinə]

- Chinese: 支那 Zhīnà (obsolete and considered offensive due to historical Japanese usage; originated from early Chinese translations of Buddhist texts in Sanskrit)

- Chinese: 震旦 Zhèndàn transcription of the Sanskrit/Pali "Cīnasthāna" in the Buddhist texts.

Czech: Čína (pronounced [ˈtʃiːna])

Danish: Kina

Dutch: China ([ʃiːnɑ])- English: China

Esperanto: Ĉinujo or Ĉinio, or Ĥinujo (archaic)

Estonian: Hiina (pronounced [hiːnɑ])

Filipino (Tagalog): Tsina ([tʃina])

Finnish: Kiina (pronounced [kiːnɑ])- French: Chine ([ʃin])

Galician: China (pronounced [tʃina])

Georgian: ჩინეთი (pronounced [tʃinɛtʰi])- German: China ([ˈçiːna], in the southern part of the German-speaking area also [ˈkiːna])

Greek: Κίνα (Kína) ([ˈcina])

Hindustani: Cīn चीन or چين (IPA [ˈtʃiːn])

Hungarian: Kína ([ˈkiːnɒ])

Icelandic: Kína ([kʰina])

Indonesian: Cina ([tʃina], unofficial), Tiongkok (for country), Tionghoa (for ethnicity, culture, and other non-country subject)

Interlingua: China

Irish: An tSín ([ən ˈtʲiːnʲ])

Italian: Cina ([ˈtʃiːna])- Japanese: Shina (支那) – considered offensive in China, now largely obsolete in Japan and avoided out of deference to China (the name Chūgoku is used instead); See Shina (word) and kotobagari.

Khmer: ចិន ( [cən])

Korean: Jina (지나)

Latvian: Ķīna ([ˈciːna])

Lithuanian: Kinija ([kʲɪnʲijaː])

Macedonian: Кина (Kina) ([kinə])

Malay: Cina ([tʃina]) – considered less offensive than the historic Tongsan but some have argued for use of the Indonesian word Tionghua

Malayalam: Cheenan/Cheenathi

Maltese: Ċina ([ˈtʃiːna])

Marathi: Cīn चीन (IPA [ˈtʃiːn])

Nepali: Cīn चीन (IPA [ˈtʃiːn])

Norwegian: Kina ([çiːnɑ][stress and toneme?] or [ʂiːnɑ])[stress and toneme?]

Pahlavi: Čīnī

Persian: Chīn چين ([tʃin])

Polish: Chiny ([ˈçinɨ])

Portuguese: China ([ˈʃinɐ])

Romanian: China ([ˈkina])

Serbo-Croatian: Kina or Кина ([ˈkina])

Slovak: Čína ([ˈtʃiːna])

Slovenian: Kitajska ([kiˈtajska])- Spanish: China ([ˈtʃina])

Swedish: Kina ([²ɕiːna])

Sylheti: ꠌꠤꠘ ("sin")

Tamil: Cīnā (சீனா)

Thai: จีน RTGS: Chin ( [t͡ɕiːn])

Tibetan: Rgya Nag (

རྒྱ་ནག་)

Turkish: Çin ([tʃin])

Vietnamese: Chấn Đán (in Buddhist texts).

Welsh: Tsieina ([ˈtʃəina])

Seres, Ser, Serica

Sēres (Σῆρες) was the Ancient Greek and Roman name for the northwestern part of China and its inhabitants. It meant "of silk," or "land where silk comes from." The name is thought to derive from the Chinese word for silk, "sī" (絲/丝). It is itself at the origin of the Latin for silk, "sērica". See the main article Serica for more details.

Ancient Greek: Σῆρες Seres, Σηρικός Serikos

Latin: Serica

This may be a back formation from sērikos (σηρικός), "made of silk", from sēr (σήρ), "silkworm", in which case Sēres is "the land where silk comes from."

Sinae, Sin

A mid-15th century map based on Ptolemy's manuscript Geography. Serica and Sina are marked as separate countries (top right and right respectively).

Sīnae was an ancient Greek and Roman name for some people who dwelt south of the Seres (Serica) in the eastern extremity of the inhabitable world. References to the Sinae include mention of a city that the Romans called Sēra Mētropolis, which may be modern Chang'an. The Latin prefixes Sino- and Sin-, which are traditionally used to refer to China and the Chinese, came from Sīnae.[61] It is generally thought that Chīna, Sīna and Thīna are variants that ultimately derived from Qin, which was the westernmost state in China that eventually formed the Qin Dynasty.[49] There are however other opinions on its etymology (See section on China above). Henry Yule thought that this term may have come to Europe through the Arabs, who made the China of the farther east into Sin, and perhaps sometimes into Thin.[62] Hence the Thin of the author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, who appears to be the first extant writer to employ the name in this form; hence also the Sinæ and Thinae of Ptolemy.[48][49]

Some denied that Ptolemy's Sinae really represented the Chinese as Ptolemy called the country Sērice and the capital Sēra, but regarded them as distinct from Sīnae.[49][63]Marcian of Heraclea (a condenser of Ptolemy) tells us that the "nations of the Sinae lie at the extremity of the habitable world, and adjoin the eastern Terra incognita". The 6th century Cosmas Indicopleustes refers to a "country of silk" called Tzinista, which is understood as referring to China, beyond which "there is neither navigation nor any land to inhabit".[64] It seems probable that the same region is meant by both. According to Henry Yule, Ptolemy's misrendering of the Indian Sea as a closed basin meant that Ptolemy must also have misplaced the Chinese coast, leading to the misconception of Serica and Sina as separate countries.[62]

In the Hebrew Bible, there is a mention of a faraway country Sinim in the Book of Isaiah 49:12 which some had assumed to be a reference to China.[49][65] In Genesis 10:17, a tribes called the Sinites were said to be the descendants of Canaan, the son of Ham, but they are usually considered to be a different people, probably from the northern part of Lebanon.[66][67]

Arabic: Ṣīn صين

- French/English (prefix of adjectives): Sino- (i.e. Sino-American), Sinitic (the Chinese language family).

Hebrew: Sin סין

Irish: An tSín

Latin: Sīnae

Cathay

This group of names derives from Khitan, an ethnic group that originated in Manchuria and conquered parts of Northern China early tenth century forming the Liao dynasty, and later in the twelfth century dominated Central Asia as the Kara Khitan Khanate. Due to long period of domination of Northern China and then Central Asia by these nomadic conquerors, the name Khitan become associated with China to the people in and around the northwestern region. Muslim historians referred to the Kara Khitan state as Khitay or Khitai; they may have adopted this form of "Khitan" via the Uyghurs of Kocho in whose language the final -n or -ń became -y.[68] The name was then introduced to medieval and early modern Europe through Islamic and Russian sources.[69] In English and in several other European languages, the name "Cathay" was used in the translations of the adventures of Marco Polo, which used this word for northern China. Words related to Khitay are still used in many Turkic and Slavic languages to refer to China. However, its use by Turkic speakers within China, such as the Uyghurs, is considered pejorative by the Chinese authority who tried to ban it.[69]

Belarusian: Кітай (Kitay)

Bulgarian: Китай (Kitay, IPA: [kiˈtaj])

Classical Mongolian: Kitad[70]

- English: Cathay

Kazan Tatar: Кытай (Qıtay)

Medieval Latin: Cataya, Kitai

Mongolian: Хятад (Khyatad) (the name for China used in the State of Mongolia)

Buryat: Хитад (Khitad)

Portuguese: Catai ([kɐˈtaj])

Russian: Китай (Kitáy, IPA: [kʲɪˈtaj])

Slovene: Kitajska ([kiːˈtajska])

Spanish: Catay

Kazakh: Қытай (Qıtay)

Kyrgyz: Кытай ("Qıtay")

Tajik: Хитой ("Khitoy")

Turkmen: Hytaý ("Хытай")

Ukrainian: Китай (Kytai)

Uyghur:

خىتاي, ULY: Xitay

Uzbek: Xitoy (Хитой)

There is no evidence that either in the 13th or 14th century, Cathayans, i.e. Chinese, travelled officially to Europe, but it is possible that some did, in unofficial capacities, at least in the 13th century. During the campaigns of Hulagu (the grandson of Genghis Khan) in Persia (1256–65), and the reigns of his successors, Chinese engineers were employed on the banks of the Tigris, and Chinese astrologers and physicians could be consulted. Many diplomatic communications passed between the Hulaguid Ilkhans and Christian princes. The former, as the great khan's liegemen, still received from him their seals of state; and two of their letters which survive in the archives of France exhibit the vermilion impressions of those seals in Chinese characters—perhaps affording the earliest specimen of those characters to reach western Europe.

Tabgach

"Tabgach" came from the metatheses of "Tuoba" (*t'akbat), a dominant tribe of the Xianbei, and the surname of the Northern Wei Dynasty in the 5th century before sinicisation. It referred to Northern China, which was dominated by half-Xianbei, half-Chinese people.

Byzantine Greek: Taugats

Orhon Kok-Turk: Tabgach (variations Tamgach)

Nikan

Nikan (Manchu: ᠨᡳᡴᠠᠨ, means"Han ethnicity") was a Manchu ethnonym of unknown origin that referred specifically to the ethnic group known in English as the Han Chinese; the stem of this word was also conjugated as a verb, nikara(-mbi), and used to mean "to speak the Chinese language." Since Nikan was essentially an ethnonym and referred to a group of people (i.e., a nation) rather than to a political body (i.e., a state), the correct translation of "China" into the Manchu language is Nikan gurun, literally the "Nikan state" or "country of the Nikans" (i.e., country of the Hans).[citation needed]

This exonym for the Han Chinese is also used in the Daur language, in which it appears as Niaken ([njakən] or [ɲakən]).[71] As in the case of the Manchu language, the Daur word Niaken is essentially an ethnonym, and the proper way to refer to the country of the Han Chinese (i.e., "China" in a cultural sense) is Niaken gurun, while niakendaaci- is a verb meaning "to talk in Chinese."

Kara

Japanese: Kara (から; variously written in kanji as 唐 or 漢). An identical name was used by the ancient and medieval Japanese to refer to the country that is now known as Korea, and many Japanese historians and linguists believe that the word "Kara" referring to China and/or Korea may have derived from a metonymic extension of the appellation of the ancient city-states of Gaya.

The Japanese word karate (空手, lit. "empty hand") is derived from the Okinawan word karatii (唐手, lit. "Tang/Chinese hand") and refers to Okinawan martial arts; the character for kara was changed to remove the connotation of the style originating in China.

Morokoshi

Japanese: Morokoshi (もろこし; variously written in kanji as 唐 or 唐土). This obsolete Japanese name for China is believed to have derived from a kun reading of the Chinese compound 諸越 Zhūyuè or 百越

Bǎiyuè as "all the Yue" or "the hundred (i.e., myriad, various, or numerous) Yue," which was an ancient Chinese name for the societies of the regions that are now southern China.

The Japanese common noun tōmorokoshi (トウモロコシ, 玉蜀黍), which refers to maize, appears to contain an element cognate with the proper noun formerly used in reference to China. Although tōmorokoshi is traditionally written with Chinese characters that literally mean "jade Shu millet," the etymology of the Japanese word appears to go back to "Tang morokoshi," in which "morokoshi" was the obsolete Japanese name for China as well as the Japanese word for sorghum, which seems to have been introduced into Japan from China.

Mangi

From Chinese Manzi (southern barbarians). The division of North China and South China under the Jin dynasty and Song dynasty weakened the idea of a unified China, and it was common for non-Han Chinese to refer to the politically disparate North and South by different names for some time. While Northern China was called Cathay, Southern China was referred to as Mangi. Manzi often appears in documents of the Mongol Yuan dynasty. The Mongols also called Southern Chinese "Nangkiyas" or "Nangkiyad", and considered them ethnically distinct from North Chinese. The word "Manzi" also reached the Western world as "Mangi" (as used by Marco Polo), also in Persian as Machin ماچين and Arabic as Māṣīn ماصين. The name is also commonly found on medieval maps. However, the Chinese themselves considered "Manzi" to be derogatory and never used it as a self appellation.[72][73]

- Chinese: Manzi (蠻子)

Latin: Mangi

See also

- Chinese romanization

- List of country name etymologies

- Names of the Qing dynasty

- Names of India

- Names of Japan

- Names of Korea

- Names of Vietnam

Île-de-France, similar French concept

References

Citations

^ ab Wilkinson 2015, p. 191.

^ Bilik, Naran (2015), "Reconstructing China beyond Homogeneity", Patriotism in East Asia, Political Theories in East Asian Context, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 105.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ 7qiji.com. "China's 7 wonders (中國七大奇蹟)[permanent dead link]." 何尊 Retrieved on 2010-05-01.

^ Joseph Esherick, "How the Qing Became China," in Empire to Nation: Historical Perspectives on the Making of the Modern World (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), pp. 232–233

^ Matteo Ricci , Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. China in the 16th Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci,1583-1610, trans.(New York, Random House, 1942,1953)p.3-6

^ John Livingston Nevius, China and the Chinese (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1869), p.22.

^ ab Zarrow, Peter Gue (2012). After Empire:The Conceptual Transformation of the Chinese State, 1885-1924. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804778688., p. 93-94.

^ Jiang 2011, p. 103.

^ Peter K Bol, "Geography and Culture: Middle-Period Discourse on the Zhong Guo: The Central Country," (2009), 1, 26.

^ Esherick, "How the Qing Became China," pp. 232–233

^ Fourmont, Etienne. "Linguae Sinarum Mandarinicae hieroglyphicae grammatica duplex, latinè, & cum characteribus Sinensium. Item Sinicorum Regiae Bibliothecae librorum catalogus… (A Chinese grammar published in 1742 in Paris)". Archived from the original on 2012-03-06.

^ Hauer 2007, p. 117.

^ Dvořák 1895, p. 80.

^ Wu 1995, p. 102.

^ Zhao (2006), p. 7.

^ Zhao (2006), p. 4, 7–10, 12–14.

^ Mosca 2011, p. 94.

^ Dunnell 2004, p. 77.

^ Dunnell 2004, p. 83.

^ Elliott 2001, p. 503.

^ Dunnell 2004, pp. 76-77.

^ Cassel 2011, p. 205.

^ Cassel 2012, p. 205.

^ Cassel 2011, p. 44.

^ Cassel 2012, p. 44.

^ Perdue 2009, p. 218.

^ Elliot 2000, p. 638.

^ Barabantseva 2010, p. 20.

^ Esherick 2006, p. 232.

^ Esherick 2006, p. 251.

^ Liang quoted in Joseph Esherick, "How the Qing Became China," in Empire to Nation: Historical Perspectives on the Making of the Modern World (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), p. 235, from Liang Qichao, "Zhongguo shi xulun" Yinbinshi heji 6:3 and in Lydia He Liu, The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), pp. 77–78.

^ Douglas R. Reynolds. China, 1898–1912: The Xinzheng Revolution and Japan. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1993

ISBN 0674116607), pp. 215–16 n. 20.

^ Henrietta Harrison. China (London: Arnold; New York: Oxford University Press; Inventing the Nation Series, 2001.

ISBN 0-340-74133-3), pp. 103–104.

^ Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Rev. and enl., 2000

ISBN 0-674-00247-4 ), 132.

^ Lydia He. LIU; Lydia He Liu (30 June 2009). The Clash of Empires: the invention of China in modern world making. Harvard University Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-674-04029-8.

^ Wilkinson, p. 132.

^ Wilkinson 2012, p. 191.

^ Between 1967 and 2014, "Cina"/"China" is used. It was officially reverted to "Tiongkok" in 2014 by order of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono due to anti-discriminal reasons, but usage is unforced.

^ 孔穎達《春秋左傳正義》:「中國有禮儀之大,故稱夏;有服章之美,謂之華。」

^ Dillon, Michael. China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 9781136791413.

^ H. Mark Lai (4 May 2004). Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions. AltaMira Press. pp. 7&ndash, 8. ISBN 9780759104587.

^ Tai, Pao-tsun (2007). The Concise History of Taiwan (Chinese-English bilingual ed.). Nantou City: Taiwan Historica. p. 52. ISBN 9789860109504.

^ "Entry #60161 (有唐山公,無唐山媽。)". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan] (in Chinese and Hokkien). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011.CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link)

^ 《中華民國教育部重編國語辭典修訂本》:「以其位居四方之中,文化美盛,故稱其地為『中華』。」

^ Wilkinson. Chinese History: A Manual. p. 32.

^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed (AHD4). Boston and New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 2000, entries china, Qin, Sino-.

^ Axel Schuessler (2006). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0824829759.

^ abc Yule, Henry. Cathay and the Way Thither. pp. 2–3. ISBN 8120619668. "There are reasons however for believing the word China was bestowed at a much earlier date, for it occurs in the Laws of Manu, which assert the Chinas to be degenerate Kshatriyas, and the Mahabharat, compositions many centuries older that imperial dynasty of Ts'in ... And this name may have yet possibly been connected with the Ts'in, or some monarchy of the like title; for that Dynasty had reigned locally in Shen si from the ninth century before our era..."

^ abcde Samuel Wells Williams (2006). The Middle Kingdom: A Survey of the Geography, Government, Literature, Social Life, Arts and History of the Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 978-0710311672.

^ "China". Oxford English Dictionary (1989).

ISBN 0-19-957315-8.

^ ""The Very Great Kingdom of China"". The Book of Duarte Barbosa. ISBN 81-206-0451-2. In the Portuguese original, the chapter is titled "O Grande Reino da China".

^ Eden, Richard (1555). Decades of the New World: "The great China whose kyng is thought the greatest prince in the world."

Myers, Henry Allen (1984). Western Views of China and the Far East, Volume 1. Asian Research Service. p. 34.

^ Wade, Geoff. "The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name 'China'", Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 188, May 2009. pp. 8-11

^ Berthold Laufer (1912). "The Name China". T'oung Pao. 13 (1): 719–726. doi:10.1163/156853212X00377.

^ Yule, Henry. Cathay and the Way Thither. pp. 3–7. ISBN 8120619668.

^ ab Wade, pp. 12–13.

^ Bodde, Derk. Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe, eds. The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC - AD 220. pp. 20&ndash, 21. ISBN 9780521243278.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ ab Wade, Geoff. "The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name 'China'". Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 188, May 2009, p. 20.

^ Liu, Lydia He, The clash of empires, p. 77.

ISBN 9780674019959. "Scholars have dated the earliest mentions of Cīna to the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata and to other Sanskrit sources such as the Hindu Laws of Manu."

^ Wade, Geoff (May 2009). "The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name 'China'" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 188. Retrieved 4 October 2011. "This thesis also helps explain the existence of Cīna in the Indic Laws of Manu and the Mahabharata, likely dating well before Qin Shihuangdi."

^ "Sino-". Merriam-Webster.

^ ab Yule, Henry. Cathay and the Way Thither, Volume 1. p. xxxvii. ISBN 8120619668.

^ Yule, Henry. Cathay and the Way Thither, Volume 1. p. xl. ISBN 8120619668.

^ Stefan Faller. "The World According to Cosmas Indicopleustes – Concepts and Illustrations of an Alexandrian Merchant and Monk". Transcultural Studies. 1: 193–232.

^ Sir William Smith, John Mee Fuller, eds. (1893). Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible. p. 1328.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ John Kitto (ed.). A cyclopædia of biblical literature. p. 773.

^ Sir William Smith, John Mee Fuller, eds. (1893). Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible. p. 1323.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ Sinor, D. (1998), "Chapter 11 – The Kitan and the Kara Kitay", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E., History of Civilisations of Central Asia, 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

^ ab James A. Millward and Peter C. Perdue (2004). S.F.Starr, ed. Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 43. ISBN 9781317451372.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Yang, Shao-yun (2014). "Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500-1200". In Fiaschetti, Francesca; Schneider, Julia. Political Strategies of Identity Building in Non-Han Empires in China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 23.

^ Samuel E. Martin, Dagur Mongolian Grammar, Texts, and Lexicon, Indiana University Publications Uralic and Altaic Series, Vol. 4, 1961

^ Henry Yule, Henri Cordier (1967), Cathay and the Way Thither: Preliminary essay on the intercourse between China and the western nations previous to the discovery of the Cape route, p. 177

^ Tan Koon San. Dynastic China: An Elementary History. The Other Press. p. 247. ISBN 9789839541885.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

- Books

Cassel, Par Kristoffer (2011). Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199792127. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Cassel, Par Kristoffer (2012). Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199792054. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Dvořák, Rudolf (1895). Chinas religionen ... (in German). Volume 12; Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Aschendorff (Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung). ISBN 0199792054. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804746842. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Hauer, Erich (2007). Corff, Oliver, ed. Handwörterbuch der Mandschusprache (in German). Volume 12; Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3447055286. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Perdue, Peter C. (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674042026. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute

Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088467.

Wu, Shuhui (1995). Die Eroberung von Qinghai unter Berücksichtigung von Tibet und Khams 1717 - 1727: anhand der Throneingaben des Grossfeldherrn Nian Gengyao (in German). Volume 2 of Tunguso Sibirica (reprint ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3447037563. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Zhao, Gang (2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). 32 (1). Sage Publications. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014.