History of the administrative divisions of China before 1912

The history of the administrative divisions of the Imperial China is quite complex. Across history, what is called 'China' has taken many shapes, and many political organizations. For various reasons, both the borders and names of political divisions have changed—sometimes to follow topography, sometimes to weaken former states by dividing them, and sometimes to realize a philosophical or historical ideal. For recent times, the number of recorded tiny changes is quite large; by contrast, the lack of clear, trustworthy data for ancient times forces historians and geographers to draw approximate borders for respective divisions. But thanks to imperial records and geographic descriptions, political divisions may often be redrawn with some precision. Natural changes, such as changes in a river's course (known for the Huang He, but also occurring for others), or loss of data, still make this issue difficult for ancient times.

Contents

1 Summary

2 Ancient times

3 Jun under the Qin dynasty

4 Zhou under the Han dynasty

5 Provinces during the Era of Fragmentation

6 Zhou under Sui dynasty

7 Circuits under the Tang dynasty

8 Provinces under the Liao, Song and Jurchen Jin dynasties

9 Provinces under the Yuan dynasty

10 Provinces under the Ming dynasty

11 Provinces and Feudatory Regions under the Qing dynasty

12 See also

13 References

14 Sources and further reading

15 External links

Summary

Historical Administrative Divisions in China | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynasty | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary | Quaternary |

| Qin | Commandery (郡, jùn) | County (縣/县, xiàn) | | |

Han, Jin | Province (州, zhōu) | Commandery | County | |

| Sui | "Prefecture" (many smaller 州) | County | | |

Tang, Liao | Circuit (道, dào) | Prefecture (smaller: 州; larger: 府, fǔ) | County | |

Song and Jin | Circuit (路, lù) | Prefecture (smaller: 州; larger: 府; military: 軍/军, jūn); industrial: 監/监, jiān | County | |

| Yuan | Province (省, shěng) | Circuit (道, dào) | Prefecture (larger: 府, fǔ; smaller: 州, zhōu) | County |

| Ming | Directly administered province Zhílì (直隸/直隶) Province (省) | Prefecture (府, Fǔ) | Department (州) | County |

| Qing | Directly administered province (直隸/直隶) Province (省) | Prefecture (府, Fǔ) Independent department (直隸州/直隶州) Independent subprefecture (直隸廳/直隶厅) | County (縣/县) Department (州) Subprefecture (廳/厅, Tīng) | |

Ancient times

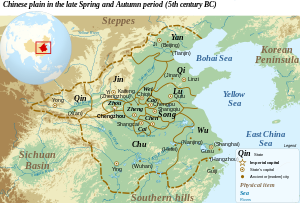

Chinese plain 5c. BC.

Before the establishment of the Qin dynasty, China was ruled by a network of kings, nobles, and tribes. There was no unified system of administrative divisions. According to ancient texts, China in the Xia and Zhou dynasties consisted of nine zhou, but various texts differ as to the names and even functions of these zhous.

During the Zhou dynasty, the nation was nominally controlled by the "Son of Heaven". In reality, however, the country was divided into competing states, each with a hereditary head, variously styled "prince", "duke", or "king". The rivalry of these groups culminated in the Warring States period, which ended with the victory of Qin.

Jun under the Qin dynasty

Borders of the commanderies of the Qin Empire.

After the Kingdom of Qin managed to subdue the rest of China in 221 BC, the First Emperor divided his realm into relatively small commanderies, which were divided into still smaller counties. Repudiating the fiefs of the Zhou, both levels were centrally and tightly controlled as part of a meritocratic system. There was also a separately-administered capital district known as the Neishi.

The commanderies were grouped into four large divisions: Guanzhong, named for the lower valley of the Wei River around the capital "within the pass" leading to the North China Plain; Hebei north of the Yellow River; Henan south of it; and Jianghan, named for the Yangtze and Han rivers and incorporating the conquered lands of modern Hunan and Guangdong. Control over some of these, particularly Fujian ("Min Commandery"), was particularly loose.

Commanderies of the Qin Empire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area Traditional Simplified | Commandery | Chinese Name | Counties & Circuits | |

Trad. | Simp. | |||

| Guanzhong 關中地區 关中地区 | Neishi Zhiguan | 內史直管 | 41 | |

Longxi | 隴西郡 | 陇西郡 | 21 | |

Shang | 上郡 | 21 | ||

Beidi | 北地郡 | 15 | ||

Yunzhong | 雲中郡 | 云中郡 | 12 | |

Jiuyuan | 九原郡 | 8 | ||

Henan 河南地區 河南地区 | Sanchuan | 三川郡 | 22 | |

Yingchuan | 潁川郡 | 颍川郡 | 23 | |

Dang | 碭郡 | 砀郡 | 22 | |

Dong | 東郡 | 东郡 | 26 | |

Xue | 薛郡 | 22 | ||

Donghai | 東海郡 | 东海郡 | 18 | |

Sichuan | 四川郡 | 25 | ||

Huaiyang | 淮陽郡 | 淮阳郡 | 27 | |

Nanyang | 南陽郡 | 南阳郡 | 27 | |

Linzi | 臨淄郡 | 临淄郡 | 10 | |

Jibei | 濟北郡 | 济北郡 | 9 | |

Taishan | 泰山郡 | 9 | ||

Langxie | 琅邪郡 | 6 | ||

Jiaodong | 膠東郡 | 胶东郡 | 8 | |

Jiaoxi | 膠西郡 | 胶西郡 | 8 | |

Chengyang | 城陽郡 | 城阳郡 | 5 | |

Hebei 河北地區 河北地区 | Hedong | 河東郡 | 河东郡 | 19 |

Henei | 河內郡 | 19 | ||

Shangdang | 上黨郡 | 上党郡 | 21 | |

Taiyuan | 太原郡 | 13 | ||

Dai | 代郡 | 11 | ||

Yanmen | 雁門郡 鴈門郡 | 雁门郡 | 17 | |

Handan | 邯鄲郡 | 邯郸郡 | 11 | |

Julu | 鉅鹿郡 | 巨鹿郡 | 10 | |

Hengshan | 恆山郡 | 恒山郡 | 22 | |

Qinghe | 清河郡 | 4 | ||

Hejian | 河間郡 | 河间郡 | 10 | |

Guangyang | 廣陽郡 | 广阳郡 | 9 | |

Youbeiping | 右北平郡 | 16 | ||

Shanggu | 上谷郡 | 12 | ||

Yuyang | 漁陽郡 | 渔阳郡 | 12 | |

Liaoxi | 遼西郡 | 辽西郡 | 7 | |

Liaodong | 遼東郡 | 辽东郡 | 3 | |

Jianghan 江漢地區 江汉地区 | Hanzhong | 漢中郡 | 汉中郡 | 12 |

Shu | 蜀郡 | 18 | ||

Ba | 巴郡 | 11 | ||

Nan | 南郡 | 20 | ||

Jiujiang | 九江郡 | 13 | ||

Lujiang | 廬江郡 | 庐江郡 | 5 | |

Hengshan | 衡山郡 | 5 | ||

Guiji | 會稽郡 | 会稽郡 | 27 | |

Changsha | 長沙郡 | 长沙郡 | 6 | |

Dongting | 洞庭郡 | 11 | ||

Cangwu | 蒼梧郡 | 苍梧郡 | 13 | |

Xiang | 象郡 | 2 | ||

Nanhai | 南海郡 | 5 | ||

Guilin | 桂林郡 | 5 | ||

Minzhong | 閩中郡 | 闽中郡 | 1 | |

There were also four other commanderies—Zhang (鄣郡), Zhouling (州陵郡), Jianghu (江湖郡), and Wuqian (巫黔郡)—and 23 unaffiliated counties.

Zhou under the Han dynasty

Han provinces, c. 190

The Han dynasty initially added a top level of "kingdoms" or "principalities" (王国, wángguó), each headed by a local king or a prince of the imperial family. From the establishment of the dynasty, however, the tendency was slowly absorb this quasi-federal structure into the imperial bureaucracy. After the Rebellion of the Seven States, the system was standardized, replacing the kingdoms and principalities with thirteen provinces (州, zhōu).

- Provinces

- Commanderies

- Counties

Provinces of the Han and Western Jin dynasties | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximant extent in terms of modern locations | |

| Ancient name | Modern location | |||||

Bingzhou* | 并州 | 并州 | Bīngzhōu | Jinyang | southwest of Taiyuan | Shanxi |

Jiaozhou* | 交州 | 交州 | Jiāozhōu | Longbian | East of Hanoi | northern Vietnam |

Jingzhou* | 荆州 | 荆州 | Jīngzhōu | Jiangling | Hubei, Hunan | |

Jizhou* | 冀州 | 冀州 | Jìzhōu | Xindu | Jizhou City | southern Hebei |

Liangzhou* | 涼州 | 凉州 | Liángzhōu | Guzang | Wuwei | western Gansu[1] |

Qingzhou* | 青州 | 青州 | Qīngzhōu | Linzi | east of Zibo | eastern Shandong |

Xuzhou* | 徐州 | 徐州 | Xúzhōu | Pengcheng | Xuzhou | northern Jiangsu |

Yangzhou* | 揚州 | 扬州 | Yángzhōu | Jianye | Nanjing | southern Jiangsu, southern Anhui, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shanghai |

Yanzhou* | 兗州 | 兖州 | Yǎnzhōu | Linqiu | northwest of Yuncheng County | western Shandong |

Yizhou* | 益州 | 益州 | Yìzhōu | Chengdu | central Sichuan, Guizhou | |

Yongzhou* | 雍州 | 雍州 | Yōngzhōu | Chang'an | northwest of Xi'an | central Shaanxi |

Youzhou* | 幽州 | 幽州 | Yōuzhōu | Zhuoxian | northern Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin | |

Yuzhou* | 豫州 | 豫州 | Yùzhōu | Chenxian | Huaiyang | southern Henan, northern Anhui |

| Pingzhou | 平州 | 平州 | Píngzhōu | Xiangping | Liaoyang | Liaoning, northern Korea |

| Qinzhou | 秦州 | 秦州 | Qínzhōu | Jixian | east of Gangu | southern Gansu |

| Liangzhou | 梁州 | 梁州 | Liángzhōu | Nanzheng | Hanzhong | southern Shaanxi, eastern Sichuan, Chongqing |

| Ningzhou | 寧州 | 宁州 | Níngzhōu | Dianchi | southeast of Kunming | Yunnan |

| Guangzhou | 廣州 | 广州 | Guǎngzhōu | Panyu | Guangzhou | Guangdong, eastern Guangxi |

| Sizhou | 司州 | 司州 | Sīzhōu | Luoyang | central Henan, southern Shanxi | |

* One of the original provinces established during the Eastern Han dynasty

Ping was formed out of You; Qin out of Liang (涼/凉); Liang (梁) and Ning out of Yi; and Guang out of Jiao. Jiao had been established from a territory called Jiaozhi (交趾); Si too was a new creation, its territory formerly administered by a metropolitan commandant (司隷校尉, Sīlì xiàowèi) with capacities similar to the provincial governors'. Shuofang (朔方, Shuòfāng), a similar territory in northern Shaanxi, was merged into Bing rather than becoming a full province in its own right.

Provinces during the Era of Fragmentation

Administrative divisions of Eastern Jin dynasty, as of 382 AD

Throughout the Han dynasty, the Three Kingdoms period, and the early period of Jin dynasty, the administrative division system remained intact. This changed, however, with the invasion of nomadic tribes from the north in 310s, who disrupted the unity of China and set up a variety of governments.

After the Yongjia Disaster, Jin dynasty lost a significant amount of territories in the north. Sixteen Kingdoms were established by barbarians in the Yellow River plain, while the court of Jin dynasty shifted to Jiankang and survived in the south as Eastern Jin. Among previous provinces of Jin dynasty, only a few remained. They include:

- Yangzhou

- Jiangzhou

- Jingzhou

- Ningzhou

- Jiaozhou

- Guangzhou

- Yuzhou (only the southern part)

- Xuzhou (only the southern part)

[2]

While barbarians occupied the north, many Han ethnics moved south along with the court of Jin dynasty. Those people gathered in some small towns of the south and formed communities corresponding to their original hometowns. Gradually, their population exceeded the local population of those small towns. Thus, the Jin government established many "Emigrant prefectures or counties" (Qiaozhou) in those small towns and named them based on the hometowns of immigrants. For example, Yanzhou, Qingzhou and Youzhou were ceded to barbarians kingdoms, but there were Southern Yanzhou, Southern Qingzhou and Southern Youzhou in the south.

Administrative divisions of Liu Song dynasty (Southern dynasties)

Eastern Jin launched several expeditions in its last years and regained many territories. When the Liu Song replaced Eastern Jin as the first Southern Dynasties, it re-constructed the administrative divisions. For example, Yanzhou, Yongzhou and Jizhou were restored. During the reign of Emperor Xiaowu, Liu Song had 22 prefectures (州, Zhou), 238 sub-prefectures (郡, Jun) and 1179 counties (Xian, 县):

- Yangzhou

- Xuzhou

- Southern Xuzhou

- Yanzhou

- Southern Yanzhou

- Yuzhou

- Southern Yuzhou

- Jiangzhou

- Qingzhou

- Jizhou

- Sizhou

- Jingzhou

- Yingzhou

- Xiangzhou

- Yongzhou

- Liangzhou

- Qinzhou

- Yizhou

- Ningzhou

- Guangzhou

- Jiaozhou

- Yuezhou

[3]

Later, due to the conflict with Northern Wei and the change of territories, Liu Song's prefecture divisions changed for several times. Liu Song's successors, Southern Qi and Liang dynasty, kept the bulk part of Liu Song's administrative divisions except for the Shandong peninsula which was lost again to the north. Liang dynasty also set first counties on the Hainan Island. The last of Southern Dynasties, the Chen dynasty, however, lost every prefecture to the north of the Yangtze river.

[4]

Administrative divisions of Northern Wei dynasty (Northern Dynasties) as of 464 AD

Sixteen Kingdoms of the northern China were unified by Northern Wei, the empire established by Xianbei people. Although emperors of Northern Wei tried to be Sinicized, there were serious internal struggles between Xianbei and Han styles in Northern Wei. As a result, the administrative divisions of Northern Wei were pretty complicated and unstable. The southern part of the empire used the Han-styled prefecture and county system, while the northern part of the empire was relatively poorly organized. Due to the rivalry and wars between the north and south, the area between Huai River and Yangtze River suffered significant population loss. After Northern Wei took that area from Liu Song and Southern Qi, many towns and villages there were vacant. Therefore, the administrative divisions in those areas were poorly designed. Prefectures of Northern Wei include:

- Daizhou

- Youzhou

- Yingzhou

- Pingzhou

- Dingzhou

- Jizhou (济州)

- Jizhou (冀州)

- Yanzhou

- Yuzhou

- Jingzhou (荆州)

- Luozhou (Luoyang)

- Yongzhou (Chang'an)

- Huazhou

- Qinzhou

- Weizhou

- Jingzhou (泾州)

- Sizhou

- Bingzhou

- Eastern Qinzhou

- Eastern Yongzhou

[5]

Administrative divisions (zhou, the prefectures) of China during the later phase of Southern and Northern Dynasties (Northern Qi, Northern Zhou and Chen), as of 572 AD.

To defend the invasion of Rouran, Northern Wei set many (initially six) military towns in the north, and turned the northern part into military districts. After shifting the capital city from Pingcheng to Luoyang, Northern Wei gradually lost many territories to Rouran and northwestern states. Then, those military towns rebelled and weakened the Xianbei empire. At last, the internal struggle split Northern Wei into Eastern Wei and Western Wei, which would be replaced by Northern Qi and Northern Zhou respectively. Northern Qi and Northern Zhou invaded the Southern Dynasties and occupied many counties and prefectures of Chen dynasty.

In their early years, both Northern Qi and Northern Zhou redesigned the administrative divisions. Many prefectures of the former Northern Wei dynasty were abolished and merged with each other. Some new prefectures were established. Prefectures of Northern Qi include:

- Youzhou

- Shuozhou

- Sizhou

- Eastern Xuzhou

- Yuzhou

- Yangzhou

- Luozhou

- Bingzhou

- Jinzhou (晋州)

- Huaizhou

- Eastern Yongzhou

- Jianzhou

Prefectures of Northern Zhou include:

- Yongzhou

- Jingzhou

- Xiangzhou

- Anzhou

- Xingzhou

- Jinzhou (金州)

- Liangzhou (梁州)

- Lizhou

- Yizhou

- Jiangzhou (绛州)

- Yuanzhou

- Qinzhou

- Xunzhou

- Yuzhou

- Zhongzhou

- Hezhou

- Liangzhou (凉州)

- Xiazhou

- Ningzhou

- Western Ningzhou (Xiningzhou)

- Southern Ningzhou (Nanningzhou)

At the same time, the Chen dynasty in the south had similar prefectures with its forerunners (Liu Song, Southern Qi and Liang dynasty), but some prefectures in the north and west were ceded to northern dynasties. Chen redesigned administrative divisions. It set 42 prefectures, but gave prefecture different ranks. Tier-1 prefectures of Chen dynasty include:

- Yangzhou

- Southern Yuzhou

- Jiangzhou

- Guangzhou

- Xiangzhou

- Jiaozhou (江州)

- Eastern Ningzhou (Dongningzhou)

In their later years, however, Northern Qi and Northern Zhou set up lots of new prefectures to represent areas that were not under their controls. For example, Northern Qi set up Guangzhou which were controlled by Chen dynasty and Yizhou which were controlled by Northern Zhou. In the area between Yangtze and Huai rivers, people who ran away to escape from wars in earlier periods started to move back to their hometowns. However, many of their original hometowns were destroyed completely. As a result, people from the same town gathered and established new towns and named those towns with original names. This led to the situation that many towns with the same name were established. For example, within Luozhou and Yuzhou, there were multiple counties named Chenliu.

Chen dynasty also set up a series of new immigrant prefectures along the Yangtze River, such as the Southern Xuzhou and Northern Jiangzhou, etc. The administrative division began to mess up. Northern and Southern dynasties were eventually reunified by Sui dynasty in 589. At that time, there were hundreds of prefectures all over China. Emperor Wen of Sui thus launched a major reform on the administrative division system which changed the Zhou-Jun-Xian (Prefecture, Sub-Prefecture, County) system into Zhou-Xian system, and the traditional nine provinces would be restored.

[6]

Zhou under Sui dynasty

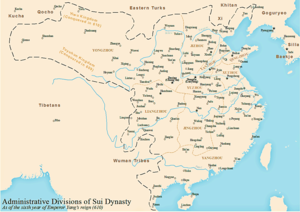

Sui provinces, ca. 610

By the time unity was finally reestablished by the Sui dynasty, the provinces had been divided and redivided so many times by different governments that they were almost the same size as commanderies, rendering the two-tier system superfluous. As such, the Sui merged the two together. In English, this merged level is translated as "prefectures". In Chinese, the name changed between zhou and jun several times before being finally settled on zhou. Based on the apocryphal Nine Province system, the Sui restored nine zhou.[7]

The Sui had 9 provinces, 190 prefectures, 1,225 counties, and about 9 million registered households or approximately 50 million people.[8]

Provinces of the Sui dynasty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximate extent in terms of modern locations | |

| Ancient name | Modern location | |||||

| Yongzhou | 雍州 | 雍州 | Yōngzhōu | ? | ? | Guanzhong, Gansu, and the Upper Yellow basin |

| Jizhou | 冀州 | 冀州 | Jìzhōu | ? | ? | Shanxi and Northern Hebei, including modern Beijing and Tianjin |

| Yanzhou | 兗州 | 兖州 | Yǎnzhōu | ? | ? | Lower Yellow River area- west of Qingzhou and east of Jizhou |

| Qingzhou | 青州 | 青州 | Qīngzhōu | ? | ? | Shandong Peninsula |

| Yuzhou | 豫州 | 豫州 | Yùzhōu | ? | ? | Henan |

| Xuzhou | 徐州 | 徐州 | Xúzhōu | ? | ? | Modern Xuzhou area- southern Shandong and northern Jiangsu |

| Liangzhou | 梁州 | 梁州 | Liángzhōu | ? | ? | Upper Yangtze- Sichuan Basin + south of the Qinling |

| Jingzhou | 荆州 | 荆州 | Jīngzhōu | ? | ? | Central Yangtze |

| Yangzhou | 揚州 | 扬州 | Yángzhōu | ? | ? | Lower Yangtze, entire SE Coast, Hainan, and Northern Vietnam |

Circuits under the Tang dynasty

Tang circuits, ca. 660

Tang circuits, ca. 742

Emperor Taizong (r. 626−649) set up 10 "circuits" (道, dào) in 627 as inspection areas for imperial commissioners monitoring the operation of prefectures, rather than a new primary level of administration. In 639, there were 10 circuits, 43 commanderies (都督府, dūdū fǔ), and 358 prefectures (州 and later 府, fǔ).[9] In 733, Emperor Xuanzong expanded the number of circuits to 15 by establishing separate circuits for the areas around Chang'an and Luoyang, and by splitting the large Shannan and Jiangnan circuits into 2 and 3 new circuits respectively. He also established a system of permanent inspecting commissioners, though without executive powers.[10]

The Tang dynasty also created military districts (藩鎮/藩镇, fānzhèn) controlled by military commissioners (節度使/节度使, jiédushǐ) charged with protecting frontier areas susceptible to foreign attack (similar to the Western marches and marcher lords). This system was eventually generalized to other parts of the country as well and essentially merged into the circuits. Just as in the West, the greater autonomy and strength of the commissioners permitted insubordination and rebellion, which in China led to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

- Circuits and Military Districts

- Commanderies and Prefectures

- Counties

Circuits of the Tang dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximate extent in terms of modern locations | ||

| Ancient name | Modern location | ||||||

Duji* | 都畿 | 都畿 | Dūjī | Henan Fu | Luoyang | Luoyang and environs | |

| Guannei | 關內 | 关内 | Guānnèi | Jingzhao Fu | Xi'an | northern Shaanxi, central Inner Mongolia, Ningxia | |

| Hebei | 河北 | 河北 | Héběi | Weizhou | Wei County, Hebei | Hebei | |

| Hedong | 河東 | 河东 | Hédōng | Puzhou | Puzhou, Yongji, Shanxi | Shanxi | |

| Henan | 河南 | 河南 | Hénán | Bianzhou | Kaifeng | Henan, Shandong, northern Jiangsu, northern Anhui | |

| Huainan | 淮南 | 淮南 | Huáinán | Yangzhou | central Jiangsu, central Anhui | ||

| Jiannan | 劍南 | 剑南 | Jiànnán | Yizhou | Chengdu | central Sichuan, central Yunnan | |

| Jiangnan | 江南 | 江南 | Jiāngnán | Jiangnanxi + Jiangnandong (see map) | |||

Qianzhong** | 黔中 | 黔中 | Qiánzhōng | Qianzhou | Pengshui | Guizhou, western Hunan | |

Jiangnanxi** | 江南西 | 江南西 | Jiāngnánxī | Hongzhou | Nanchang | Jiangxi, Hunan, southern Anhui, southern Hubei | |

Jiangnandong** | 江南東 | 江南东 | Jiāngnándōng | Suzhou | southern Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shanghai | ||

Jingji* | 京畿 | 京畿 | Jīngjī | Jingzhao Fu | Xi'an | Xi'an and environs | |

| Lingnan | 嶺南 | 岭南 | Lǐngnán | Guangzhou | Guangdong, eastern Guangxi, northern Vietnam | ||

| Longyou | 隴右 | 陇右 | Lǒngyou | Shanzhou | Ledu County, Qinghai | Gansu | |

| Shannan | 山南 | 山南 | Shānnán | Shannanxi + Shannandong (see map) | |||

Shannanxi** | 山南西 | 山南西 | Shānnánxī | Liangzhou | Hanzhong | southern Shanxi, eastern Sichuan, Chongqing | |

Shannandong** | 山南東 | 山南东 | Shānnándōng | Xiangzhou | Xiangfan | southern Henan, Hubei | |

* Circuits established under Xuanzong, as opposed to Taizong's original ten circuits.

** Circuits established under Xuanzong by dividing Taizong's Jiangnan and Shannan circuits.

Other Tang-era circuits include the West Lingnan, Wu'an, and Qinhua circuits.

Provinces under the Liao, Song and Jurchen Jin dynasties

The Five circuits of Liao in 1111 AD

Circuits of Northern Song dynasty (as of 1111 AD)

The Liao dynasty was further divided into five "circuits", each with a capital city. The general idea for this system was taken from the Balhae, although no captured Balhae cities were made into circuit capitals. The five capital cities were Shangjing (上京), meaning Supreme Capital, which is located in modern-day Inner Mongolia; Nanjing (南京), meaning Southern Capital, which is located near modern-day Beijing; Dongjing (东京), meaning Eastern Capital, which is located near modern-day Liaoning; Zhongjing (中京), meaning Central Capital, which is located in modern-day Hebei province near the Laoha river; and Xijing (西京), meaning Western Capital, which is located near modern-day Datong. Each circuit was headed by a powerful viceroy who had the autonomy to tailor policies to meet the needs of the population within his circuit. Circuits were further subdivided into administrations called fu (府), which were metropolitan areas surrounding capital cities, and outside of metropolitan areas were divided into prefectures called zhou (州), which themselves were divided into counties called xian (县).

Circuits of the Liao dynasty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chinese Name | Capital | Modern name of capital | Approximant extent in terms of modern locations |

| Shangjing | 上京道 | Linhuang Fu | Bairin Left Banner | Eastern Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia |

| Dongjing | 东京道 | Liaoyang Fu | Liaoyang | Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning and parts of Russia |

| Xijing | 西京道 | Datong Fu | Datong | Central Inner Mongolia, Northern Shanxi and Northwestern Hebei |

| Nanjing | 南京道 | Xijin Fu | Beijing | Beijing, Tianjin and Northern Hebei |

| Zhongjing | 中京道 | Dading Fu | Ningcheng | Northeastern Hebei, Western Liaoning |

The Song dynasty abolished the commissioners and renamed their circuits 路 (lù, which however is still usually translated into English as "circuits"). They also added a number of "army" prefectures (軍/军, jūn).

Circuits (路, lù)

Prefectures (larger: 府, fǔ; smaller: 州, zhōu; military: 軍/军, jūn)- Counties

Circuits of the Northern Song dynasty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximant extent in terms of modern locations | |

| Ancient name | Modern location | |||||

| Chengdufu | 成都府 | 成都府 | Chéngdūfǔ | Chengdu | central Sichuan | |

| Fujian | 福建 | 福建 | Fújiàn | Fuzhou | Fujian | |

| Guangnan East | 廣南東 | 广南东 | Guǎngnándōng | Guangzhou | eastern Guangdong | |

| Guangnan West | 廣南西 | 广南西 | Guǎngnánxī | Guizhou | Guilin | western Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan |

| Hebei East | 河北東 | 河北东 | Héběidōng | Beijing | Daming County, Hebei | eastern Hebei |

| Hebei West | 河北西 | 河北西 | Héběixī | Zhending | Zhengding County, Hebei | western Hebei |

| Hedong | 河東 | 河东 | Hédōng | Taiyuan | Shanxi | |

| Huainan East | 淮南東 | 淮南东 | Huáinándōng | Yangzhou | central Jiangsu | |

| Huainan West | 淮南西 | 淮南西 | Huáinánxī | Shouzhou | Fengtai County, Anhui | central Anhui |

| Jiangnan East | 江南東 | 江南东 | Jiāngnándōng | Jiangning Fu | Nanjing | southern Anhui |

| Jiangnan West | 江南西 | 江南西 | Jiāngnánxī | Hongzhou | Nanchang | Jiangxi |

| Jingdong East | 京東東 | 江东东 | Jīngdōngdōng | Qingzhou | Qingzhou, Shandong | eastern Shandong |

| Jingdong West | 京東西 | 江东西 | Jīngdōngxī | Nanjing | south of Shangqiu, Henan | western Shandong |

| Jinghu North | 荊湖北 | 荆湖北 | Jīnghúběi | Jiangling | Hubei, western Hunan | |

| Jinghu South | 荊湖南 | 荊湖南 | Jīnghúnán | Tanzhou | Changsha | Hunan |

| Jingji | 京畿 | 京畿 | Jīngjī | Chenliu | Chenliu, Kaifeng, Henan | Kaifeng and environs |

| Jingxi North | 京西北 | 京西北 | Jīngxīběi | Xijing | Luoyang | central Henan |

| Jingxi South | 京西南 | 京西南 | Jīngxīnán | Xiangzhou | Xiangfan | southern Henan, northern Hubei |

| Kuizhou | 夔州 | 夔州 | Kuízhōu | Kuizhou | Fengjie County, Chongqing | Chongqing, eastern Sichuan, Guizhou |

| Liangzhe | 兩浙 | 两浙 | Liǎngzhè | Hangzhou | Zhejiang, southern Jiangsu, Shanghai | |

| Lizhou | 利州 | 利州 | Lìzhōu | Xingyuan | Hanzhong | northern Sichuan, southern Shaanxi |

| Qinfeng | 秦鳳 | 秦凤 | Qínfèng | Qinzhou | Tianshui | southern Gansu |

| Yongxingjun | 永興軍 | 永兴军 | Yǒngxīngjūn | Jingzhao | Xi'an | Shaanxi |

| Zizhou | 梓州 | 梓州 | Zǐzhōu | Zizhou | Santai County, Sichuan | central southern Sichuan |

Circuits of Jurchen Jin dynasty, as of 1142 A.D.

The Jurchens invaded China proper in Jin–Song wars of the 12th century. In 1142, peace was formalized between the Jurchen Jin dynasty and the Southern Song dynasty, which was forced to cede all of North China to the Jurchens.

By the beginning of the 13th century, the Jurchens had moved their capital to Zhongdu (modern Beijing) and had adopted Chinese administrative structures. The Song dynasty also maintained the same structure over the southern half of China that they continued to govern.

Circuits of China under the Jurchen Jin dynasty and the Southern Song dynasty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximant extent in terms of modern locations | |

| Ancient name | Modern location | |||||

Jin dynasty | ||||||

| Beijing | 北京 | 北京 | Běijīng | Beijing | Ningcheng County, Inner Mongolia | eastern Manchuria |

| Damingfu | 大名府 | 大名府 | Dàmíngfǔ | Daming Fu | Daming County, Hebei | border of Henan, Hebei, Shandong |

| Dongjing | 東京 | 东京 | Dōngjīng | Dongjing | Liaoyang | Liaoning |

| Fengxiang | 鳳翔 | 凤翔 | Fèngxiáng | Fengxiang Fu | Fengxiang County, Shaanxi | western Shaanxi, eastern Gansu |

| Fuyan | 鄜延 | 鄜延 | Fūyán | Yan'an | northern Shaanxi | |

| Hebei East | 河北東 | 河北东 | Héběidōng | Hejian | Hejian, Hebei | eastern Hebei |

| Hebei West | 河北西 | 河北西 | Héběixī | Zhending | Zhengding County, Hebei | western Hebei |

| Hedong North | 河東北 | 河东北 | Hédōngběi | Taiyuan | northern Shanxi | |

| Hedong South | 河東南 | 河东南 | Hédōngnán | Pingyang | Linfen | southern Shanxi |

| Jingzhaofu | 京兆府 | 京兆府 | Jīngzhàofǔ | Jingzhao Fu | Xi'an | central Shaanxi |

| Lintao | 臨洮 | 临洮 | Líntáo | Lintao | Lintao County, Gansu | southern Gansu |

| Nanjing | 南京 | 南京 | Nánjīng | Nanjing | Kaifeng | Henan, northern Anhui |

| Qingyuan | 慶原 | 庆原 | Qìngyuán | Qingyang | eastern Gansu | |

| Shandong East | 山東東 | 山东东 | Shāndōngdōng | Yidu Fu | Qingzhou, Shandong | eastern Shandong |

| Shandong West | 山東西 | 山东西 | Shāndōngxī | Dongping Fu | Dongping County, Shandong | western Shandong |

| Shangjing | 上京 | 上京 | Shàngjīng | Shangjing | Acheng, Heilongjiang | northern Manchuria |

| Xianping | 咸平 | 咸平 | Xiánpíng | Xianping Fu | Kaiyuan, Liaoning | northern Liaoning |

| Xijing | 西京 | 西京 | Xījīng | Xijing | Datong | northern Shanxi, central Inner Mongolia |

| Zhongdu | 中都 | 中都 | Zhōngdū | Zhongdu | Beijing | northern Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin |

Southern Song dynasty | ||||||

| Chengdufu | 成都府 | 成都府 | Chéngdūfǔ | Chengdu | central Sichuan | |

| Fujian | 福建 | 福建 | Fújiàn | Fuzhou | Fujian | |

| Guangnan East | 廣南東 | 广南东 | Guǎngnándōng | Guangzhou | eastern Guangdong | |

| Guangnan West | 廣南西 | 广南西 | Guǎngnánxī | Jingjiang Fu | Guilin | western Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan |

| Huainan East | 淮南東 | 淮南东 | Huáinándōng | Yangzhou | central Jiangsu | |

| Huainan West | 淮南西 | 淮南西 | Huáinánxī | Luzhou | Hefei | central Anhui |

| Jiangnan East | 江南東 | 江南东 | Jiāngnándōng | Jiangning Fu | Nanjing | southern Anhui |

| Jiangnan West | 江南西 | 江南 | Jiāngnánxī | Longxing Fu | Nanchang | Jiangxi |

| Jinghu North | 荊湖北 | 荊湖北 | Jīnghúběi | Jiangling | Hubei, western Hunan | |

| Jinghu South | 荊湖南 | 荊湖南 | Jīnghúnán | Tanzhou | Changsha | Hunan |

| Jingxi South | 京西南 | 京西南 | Jīngxīnán | Xiangyang Fu | Xiangfan | southern Henan, northern Hubei |

| Kuizhou | 夔州 | 夔州 | Kuízhōu | Kuizhou | Fengjie County, Chongqing | Chongqing, eastern Sichuan, Guizhou |

| Liangzhe East | 兩浙東 | 兩浙东 | Liǎngzhèdōng | Shaoxing | central and southern Zhejiang | |

| Liangzhe West | 兩浙西 | 兩浙西 | Liǎngzhèxī | Hangzhou | northern Zhejiang, southern Jiangsu, Shanghai | |

| Lizhou East | 利州東 | 利州东 | Lìzhōudōng | Xingyuan | Hanzhong | northern Sichuan, southern Shaanxi |

| Lizhou West | 利州西 | 利州西 | Lìzhōuxī | Mianzhou | Lueyang, Shaanxi | northern Sichuan, southern Gansu |

| Tongchuanfu | 潼川府 | 潼川府 | Tóngchuānfǔ | Luzhou | central southern Sichuan | |

Provinces under the Yuan dynasty

Yuan provinces in 1330 AD.

The Mongols, who succeeded in subjugating all of China under the Yuan dynasty in 1279, introduced the precursors to the modern provinces as a new primary administrative level:

Provinces (行中書省/行中书省, xíngzhōngshūshěng)

Circuits (路, lù)

Prefectures (larger: 府, fǔ; smaller: 州, zhōu)- Counties

Provinces of the Mongol Yuan dynasty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximant extent in terms of modern locations | |

| Ancient name | Modern location | |||||

| Gansu | 甘肅 | 甘肃 | Gānsù | Ganzhou | Zhangye | Gansu, Ningxia |

| Huguang | 湖廣 | 湖广 | Huguǎng | Wuchang | Hunan, western Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan | |

| Henanjiangbei | 河南江北 | 河南江北 | Hénánjiāngběi | Bianliang | Kaifeng | Henan, northern Hubei, northern Jiangsu, northern Anhui |

| Jiangxi | 江西 | 江西 | Jiāngxī | Longxing | Nanchang | Jiangxi, eastern Guangdong |

| Jiangzhe | 江浙 | 江浙 | Jiāngzhè | Hangzhou | Zhejiang, southern Jiangsu, southern Anhui, Fujian | |

| Liaoyang | 遼陽 | 辽阳 | Liáoyáng | Liaoyang | Manchuria, northeastern Korea | |

| Lingbei | 嶺北 | 岭北 | Lǐngběi | Helin | Kharkhorin (Karakorum) | Mongolia, northern Inner Mongolia |

| Shaanxi | 陝西 | 陕西 | Shǎnxi | Fengyuan | Xi'an | Shaanxi |

| Sichuan | 四川 | 四川 | Sìchuān | Chengdu | eastern and central Sichuan | |

| Yunnan | 雲南 | 云南 | Yúnnán | Zhongqing | Kunming | Yunnan, Upper Burma |

| Zhengdong | 征東 | 征东 | Zhēngdōng | Kaesong | Most of Korea | |

The area around the capital, corresponding to modern Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi, central Inner Mongolia, Beijing, and Tianjin, was called the Central Region (腹裏/腹里) and not put into any province, but was directly controlled by the Central Secretariat (Zhongshu Sheng). The Tibetan Plateau was controlled by the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Xuanzheng Yuan).

Provinces under the Ming dynasty

Administrative divisions of Ming dynasty in 1409

The Ming dynasty continued with this system and had provinces that were almost exactly the same as those in modern China proper. The differences were Huguang had not yet been split into Hubei and Hunan; Gansu and Ningxia were still part of Shaanxi; Anhui and Jiangsu were together as South Zhili; portions of what are today the provinces of Hebei, Beijing, and Tianjin were part of the province of North Zhili; and Hainan, Shanghai, and Chongqing were still parts of their original provinces at this time. This makes for a total of 15 provinces. Jiaozhi Province, formerly known as Jiaozhi, Jiaozhou, Lingnan and Rinan, was also re-established in 1407 when the area encompassing northern and central Vietnam was reconquered for the fourth time. However, the province eventually emerged as its own state in 1428 under the Later Lê dynasty of Đại Việt.

Provinces of the Ming dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Modern divisions |

| North Zhili | 北直隸 | 北直隶 | Běizhílì | Shuntian (Beijing) | 順天府(北京) | 顺天府(北京) | Beijing, Hebei, Tianjin |

| South Zhili | 南直隸 | 南直隶 | Nánzhílì | Yingtian (Nanjing) | 應天府(南京) | 应天府(南京) | Anhui, Jiangsu, Shanghai |

| Fujian | 福建 | 福建 | Fújiàn | Fuzhou (Fuzhou) | 福州府 | 福州府 | |

| Guangdong | 廣東 | 广东 | Guǎngdōng | Guangzhou (Guangzhou) | 廣州府 | 广州府 | Guangdong, Hainan |

| Guangxi | 廣西 | 广西 | Guǎngxī | Guilin (Guilin) | 桂林府 | 桂林府 | |

| Guizhou | 貴州 | 贵州 | Guìzhōu | Guiyang (Guiyang) | 貴陽府 | 贵阳府 | |

| Henan | 河南 | 河南 | Hénán | Kaifeng (Kaifeng) | 開封府 | 开封府 | |

| Huguang | 湖廣 | 湖广 | Húguǎng | Wuchang (Wuhan) | 武昌府(武漢) | 武昌府(武汉) | Hubei, Hunan |

| Jiangxi | 江西 | 江西 | Jiāngxī | Nanchang (Nanchang) | 南昌府 | 南昌府 | |

| Shaanxi | 陝西 | 陕西 | Shǎnxī | Xi'an (Xi'an) | 西安府 | 西安府 | Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi |

| Shandong | 山東 | 山东 | Shāndōng | Jinan (Jinan) | 濟南府 | 济南府 | |

| Shanxi | 山西 | 山西 | Shānxī | Taiyuan (Taiyuan) | 太原府 | 太原府 | |

| Sichuan | 四川 | 四川 | Sìchuān | Chengdu (Chengdu) | 成都府 | 成都府 | Chongqing, Sichuan |

| Yunnan | 雲南 | 云南 | Yúnnán | Yunnan (Kunming) | 雲南府(昆明) | 云南府(昆明) | |

| Zhejiang | 浙江 | 浙江 | Zhèjiāng | Hangzhou (Hangzhou) | 杭州府 | 杭州府 | |

Provinces and Feudatory Regions under the Qing dynasty

China and its provinces, near its greatest extent. (1820)

Viceroys of Qing dynasty

In 1644, Beijing fell to the Manchus, who established the Qing dynasty, the last dynasty of China. The Qing government applied the following system over China proper:

Provinces (省, shěng)

Circuits (道, dào)

Prefectures (府, fǔ), Independent Departments (直隸州/直隶州, zhílìzhōu), and Independent Subprefectures (直隸廳/厅, zhílìtīng)

Counties (縣/县, xiàn), Departments (散州, sànzhōu), Subprefectures (散廳/散厅, sàntīng)

The Qing split Shaanxi into Shaanxi and Gansu, Huguang into Hubei and Hunan, and South Zhili into Jiangsu and Anhui. Hebei was now called Zhili rather than North Zhili. These provinces are now nearly identical to modern ones. Collectively they are called the "Eighteen Provinces", a concept that endured for several centuries as synonymous to China proper.

This system applied only to China proper, with the rest of the empire under differently systems, official name is "Feudatory Regions" (藩部, fān bù). Manchuria, Xinjiang, and Outer Mongolia were ruled by military generals assigned by the Lifan Yuan, while Inner Mongolia was organized into leagues. The Qing court put Amdo under their direct control and organized it as Qinghai and also sent imperial commissioners to Tibet (Ü-Tsang and western Kham, approximately the area of the present-day Tibet Autonomous Region) to oversee its affairs.

In the late 19th century, Xinjiang and Taiwan were both set up as provinces. However, Taiwan was ceded to Imperial Japan after the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. Near the end of the dynasty, Manchuria was also reorganized into three more provinces (Fengtian, Jilin, Heilongjiang), bringing the total number to twenty-two. In 1906, the first romanization system of Mandarin Chinese, postal romanization, was officially sanctioned by the Imperial Postal Joint-Session Conference, which showed in the following table.

Provinces of the Qing dynasty (1911) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period Name (Current Name) | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Abbreviation | Capital | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese |

China proper | |||||||

| Anhwei (Anhui) | 安徽 | 安徽 | Ānhuī | 皖 wǎn | Anching (Anqing) | 安慶 | 安庆 |

| Chekiang (Zhejiang) | 浙江 | 浙江 | Zhèjiāng | 浙 zhè | Hangchow (Hangzhou) | 杭州 | 杭州 |

| Chihli (Zhili) | 直隸 | 直隶 | Zhílì | 直 zhí | Paoting (Baoding) | 保定 | 保定 |

| Fukien (Fujian) | 福建 | 福建 | Fújiàn | 閩 mǐn | Foochow (Fuzhou) | 福州 | 福州 |

| Honan (Henan) | 河南 | 河南 | Hénán | 豫 yù | Kaifeng (Kaifeng) | 開封 | 开封 |

| Hupeh (Hubei) | 湖北 | 湖北 | Húběi | 鄂 è | Wuchang (Wuchang) | 武昌 | 武昌 |

| Hunan (Hunan) | 湖南 | 湖南 | Húnán | 湘 xiāng | Changsha (Changsha) | 長沙 | 长沙 |

| Kansu (Gansu) | 甘肅 | 甘肃 | Gānsù | 甘 gān or 隴 lǒng | Lanchow (Lanzhou) | 蘭州 | 兰州 |

| Kiangsu (Jiangsu) | 江蘇 | 江苏 | Jiāngsū | 蘇 sū | Kiangning (Nanjing) Soochow (Suzhou) | 江寧(南京) 蘇州 | 江宁(南京) 苏州 |

| Kiangsi (Jiangxi) | 江西 | 江西 | Jiāngxī | 贛 gàn | Nanchang (Nanchang) | 南昌 | 南昌 |

| Kwangtung (Guangdong) | 廣東 | 广东 | Guǎngdōng | 粵 yuè | Canton (Guangzhou) | 廣州 | 广州 |

| Kwangsi (Guangxi) | 廣西 | 广西 | Guǎngxī | 桂 guì | Kweilin (Guilin) | 桂林 | 桂林 |

| Kweichow (Guizhou) | 貴州 | 贵州 | Guìzhōu | 黔 qián or 貴 guì | Kweiyang (Guiyang) | 貴陽 | 贵阳 |

| Shansi (Shanxi) | 山西 | 山西 | Shānxī | 晉 jìn | Taiyuan (Taiyuan) | 太原 | 太原 |

| Shantung (Shandong) | 山東 | 山东 | Shāndōng | 魯 lǔ | Tsinan (Jinan) | 濟南 | 济南 |

| Shensi (Shaanxi) | 陝西 | 陝西 | Shǎnxī | 陝 shǎn or 秦 qín | Sian (Xi'an) | 西安 | 西安 |

| Szechwan (Sichuan) | 四川 | 四川 | Sìchuān | 川 chuān or 蜀 shǔ | Chengtu (Chengdu) | 成都 | 成都 |

| Yunnan (Yunnan) | 雲南 | 云南 | Yúnnán | 滇 diān or 雲 yún | Yunnan (Kunming) | 雲南(昆明) | 云南(昆明) |

Manchuria (1907 incorporated into the provincial system) | |||||||

| Fengtien (Liaoning) | 奉天 | 奉天 | Fèngtiān | 奉 fèng | Mukden (Shenyang) | 盛京(瀋陽) | 盛京(沈阳) |

| Heilungkiang (Heilongjiang) | 黑龍江 | 黑龙江 | Hēilóngjiāng | 黑 hēi | Tsitsihar (Qiqihar) | 齊齊哈爾 | 齐齐哈尔 |

| Kirin (Jilin) | 吉林 | 吉林 | Jílín | 吉 jí | Kirin (Jilin) | 吉林 | 吉林 |

Sinkiang (1884 incorporated into the provincial system) | |||||||

| Sinkiang (Xinjiang) | 新疆 | 新疆 | Xīnjiāng | 新 xīn or 疆 jiāng | Tihwa (Ürümqi) | 迪化(烏魯木齊) | 迪化(乌鲁木齐) |

Feudatory Regions of the Qing dynasty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period Name (Current Name) | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Abbreviation | Capital | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | |

Tibet (Tibet) | 西藏 | 西藏 | Xīzàng | 藏 zàng | Lhasa | 喇薩(拉薩) | 喇萨(拉萨) | |

| Tsinghai (Qinghai) | 青海 | 青海 | Qīnghǎi | 青 qīng | Xining | 西寧 | 西宁 | |

| Uliastai (Outer Mongolia) | 烏里雅蘇臺(外蒙古) | 乌里雅苏台(外蒙古) | Wūlǐyǎsūtái (Ménggǔ) | — | Uliastai | 烏里雅蘇臺 | 乌里雅苏台 | |

| | Secen Khan aimag | 車臣汗部 | 车臣汗部 | Chēchénhánbù | — | Ikh Khüree (Ulaanbaatar) | 大庫倫(烏蘭巴托) | 大库伦(乌兰巴托) |

| Tüsheetu Khan aimag | 土謝圖汗部 | 土谢图汗部 | Tǔxiètúhánbù | — | Ikh Khüree | 大庫倫(烏蘭巴托) | 大库伦(乌兰巴托) | |

| Altay (Altay) | 阿爾泰 | 阿尔泰 | Āĕrtài | — | Chenghua Temple (Altay) | 承化寺(阿勒泰) | 承化寺(阿勒泰) | |

| Inner Mongolia | 內蒙古 | 内蒙古 | Nèi Měnggǔ | None (The divisions below are direct administered by Lifan Yuan) | ||||

| | Jirim aimag(Tongliao) | 哲里木盟(通遼) | 哲里木盟(通辽) | Zhélǐmù | — | ? | ? | ? |

| Josutu aimag(part of Chifeng) | 卓索圖盟 | 卓索图盟 | Zhuósuǒtú | — | ? | ? | ? | |

| Yekejuu aimag(Ordos) | 伊克昭盟(鄂尔多斯) | 伊克昭盟(鄂尔多斯) | Yīkèzhāo | — | ? | ? | ? | |

| Juuuda aimag(Chifeng) | 昭烏達盟(赤峰) | 昭乌达盟(赤峰) | Zhāowūdá | — | ? | ? | ? | |

Xilingol aimag | 錫林郭勒盟 | 锡林郭勒盟 | Xīlínguōlè | — | Beizi Temple (Xilinhot) | 貝子廟(錫林浩特) | 贝子庙(锡林浩特) | |

Ulanqab aimag | 烏蘭察布盟 | 乌兰察布盟 | Wūlánchábù | — | ? | ? | ? | |

Chahar (part of Xilingol) | 八旗察哈爾 | 八旗察哈尔 | Cháhā'ěr | — | Kalgan (Zhangjiakou) | 喀拉幹(張家口) | 喀拉干(张家口) | |

| West Hetao Mongolia | 西套蒙古 | 西套蒙古 | Xītào Měnggǔ | None (The divisions below are direct administered by Lifan Yuan) | ||||

| | Alxa | 阿拉善厄魯特旗 | 阿拉善厄鲁特旗 | Ālāshàn'èlŭtè | — | (Bayanhot) | 定遠營(巴彥浩特) | 定远营(巴彦浩特) |

| Ejin (Ejin Banner) | 額濟納土爾扈特旗 | 额济纳土尔扈特旗 | Éjìnàtŭĕrhùtè | — | ? | ? | ? | |

See also

- Administrative divisions of China

- Physiographic macroregions of China

References

^ http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1747&context=edissertations

^ Book of Jin, Treatises, Vol 14–15, Geography

^ Book of Song, Treatises, Vol 25-28, Zhou and Jun

^ Book of Southern Qi, Treatises, Vol 6-7, Zhou and Jun

^ Book of Wei, Treatises, Vol 6-8, Geography

^ Book of Sui, Treatises, Vol 24-26, Geography

^ "What were the ancient 9 provinces?" on www.chinahistoryforum.com

^ Twitchett 1979, p. 128.

^ Twitchett 1979, pp. 203, 205.

^ Twitchett 1979, p. 404.

Sources and further reading

Twitchett, D. (1979), Cambridge History of China, Sui and T'ang China 589-906, Part I, vol.3, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-21446-7.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Guy,, R. Kent (2010). Qing Governors and Their Provinces: The Evolution of Territorial Administration in China, 1644-1796. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295990187.

External links

- Summary of terms

Historical map scans – maps of various sheng, dao, fu, ting, and xian of the late Qing era.

The province in history by John Fitzgerald