Ji River

| Ji River | |||||||||

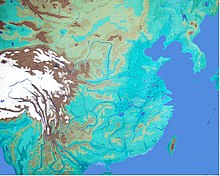

A map of China depicting the Yellow River's path between the floods of 1494 and those of the early 1850s | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 濟河 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 济河 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 濟水 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 济水 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 濟水河 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 济水河 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Other names | |||||||||

| Ji River | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 泲水 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Yuan River | |||||||||

| Chinese | 冤水 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Bendy River | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Ji River was a former river in north-eastern China which gave its name to the towns of Jiyuan and Jinan. It disappeared during one of the massive Yellow River floods of 1852, as the Yellow River shifted its course from below the Shandong Peninsula to north of it. In the process, it overtook the Ji and assumed its bed.

Contents

1 Name

2 Geography

3 History

4 Legacy

5 References

5.1 Citations

5.2 Bibliography

6 External links

Name

Jì is the pinyin romanization of the present-day Mandarin pronunciation of the Chinese name written 濟 in traditional characters and 济 in the simplified form used in mainland China. The river's Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as /*[ts]ˤəjʔ/[1] or /*ʔsliːlʔ/.[2] Ancient Chinese accounts also wrote the name with the character 泲,[3][4] and Lin Chuanjia considered this to be identical with the Yuan River that gave Yuanqu County its name.[5][6]

Geography

The Ji River changed its precise course several times over the historical period before its disappearance.[3] Generally, it traced its course from an origin near Jiyuan[7] in what is now Henan Province through Shandong to the Bohai Sea.[8]

During the Neolithic, the Ji was probably a tributary of the Yellow River, merging with its lower course in the North China Plain.[9]

At some point, its flooding shifted the lower course of the Yellow River into a separate channel, while the Ji continued to occupy its earlier path. The two rivers ran parallel to one another under the Zhou,[10]Qin, and Han.[11]

Under the Han, the Ji River's central course passed through the Great Wild Marsh (t 大野澤, s 大野泽, Dàyězé) and its mouth was in Qiansheng Commandery (千乘郡, Qiānchéng Jùn).[3]

History

The area around the Ji River was among the most densely populated in China during the Neolithic Age,[12] when its plains were a center for the Longshan[13] and Yueshi cultures.[14] It was honored as a god in ancient Chinese religion.[15]

Sima Qian lists the Ji among the rivers connected by the Honggou Canal (t 鴻溝, s 鸿沟, Hónggōu, "Canal of the Wild Geese"),[16] whose remote antiquity caused him to place it next after the works of the legendary figure Yu the Great.[17] In fact, the Heshui Canal (t 荷水運河, s 荷水运河, Héshuǐ Yùnhé) connecting the Ji to the Si was completed by soldiers under the command of King Fuchai of Wu in 483 and 482 BC in order to improve their supply lines while at war with the northern states of Qi and Jin.[10] From the Si, the Ji River then had access to the Huai River, which connected to the new course of the Yellow River through the Hongguo Canal and with the Yangtze River through the Hangou Canal just completed by Fuchai's men in 486 BC.[10]

Under the Zhou, the state of Qi was centered on the broad floodplain of the Ji.[8] It also used the "clear Ji" along with the "muddy Yellow River" as part of its borders with and defenses against the states of Yan and Zhao.[18] During antiquity, the river was a center of salt production.[3]

The river went dry during the Wei and Jin period (3rd–4th century AD).[7]

The Ji finally disappeared during one of the massive Yellow River floods of 1852,[19] as the Yellow River shifted its course from below the Shandong Peninsula to north of it. In the process, it overtook the Ji and assumed its bed. Other parts of the former course of the Ji form the present Xiaoqing River.[7]

Legacy

The Ji River was the namesake of Jiyuan ("Source of the Ji") and Jinan ("Lands South of the Ji").[7]

References

Citations

^ Baxter & al. (2014).

^ Zhengzhang (2003).

^ abcd Barbieri-Low & al. (2015), p. 943.

^ 《漢典》, 2015, s.v. "泲".mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}. (in Chinese)

^ Lin (1920).

^ Ding (2014).

^ abcd Liu (2004), p. 254.

^ ab Jun (2013), p. 145.

^ Liu (2004), p. 205.

^ abc Zhao (2015), p. 206.

^ Barbieri-Low & al. (2015), p. lxvi.

^ Chen (2015), p. 82.

^ Liu (2004), pp. 27 & 205.

^ Liu (2004), p. 207.

^ Chen (2015), p. 132.

^ Needham & al. (1971), p. 269.

^ Needham & al. (1971), p. 270.

^ Jing (2015), p. 22.

^ Pletcher & al. (2011), p. 171.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Barbieri-Low, Anthony J.; et al. (2015), Law, State, and Society in Early Imperial China, Sinica Leidensia, No. 247, Leiden: Brill.

Baxter, William Hubbard III; et al. (2014), Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction, Ver. 1.1 (PDF), Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Chen Anze; et al. (2015), The Principles of Geotourism, Heidelberg: Springer Geography.

Ding Huiying (30 Dec 2014), "关于冤句故城在山东省菏泽市牡丹区境内的考证 [Guānyú Yuānqú Gùchéng zài Shāndōng Shěng Hézé Shì Mǔdan Qū Jìngnèi de Kǎozhèng, About the Research on the Ancient City of Yuanqu in Mudan District, Heze, Shandong Province]", Official site, Heze: Heze Municipal People's Government. (in Chinese)

Jing Ai (2015), Wang Gangliu; et al., eds., A History of the Great Wall of China, New York: SCPG Publishing.

Jun Wenren (2013), Ancient Chinese Encyclopedia of Technology: Translation and Annotation of the Kaogong Ji (The Artificers' Record), Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia, No. 7, Abingdon: Routledge.

Lin Chuanjia (1920), 《大中华山东地理志》 [Dà Zhōnghuà Shāndōng Dìlǐ Zhì, Great Record of the Geography of Shandong, China], Beijing: Wuxue Shuguan. (in Chinese)

Liu Li (2004), The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States, New Studies in Archaeology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Needham, Joseph; et al. (1971), Science & Civilization in China, Vol. IV: Physics and Physical Technology, Pt. III: Civil Engineering and Nautics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pletcher, Kenneth; et al., eds. (2011), "The Major Cities of Northern China", The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places, Understanding China, New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, pp. 151–182.

Zhao Dingxin (2015), The Confucian-Legalist State: A New Theory of Chinese History, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zhengzhang Shangfang (2003), 《上古音系》 [Shànggǔ Yīnxì, Old Chinese Phonology], Shanghai: Shanghai Educational Publishing. (in Chinese)

External links

《济水》 at Baidu Baike

《济水》 at Baike.com