Siege of Syracuse (213–212 BC)

| Siege of Syracuse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second Punic War | |||||||

Archimedes Directing the Defenses of Syracuse by Thomas Ralph Spence (1895). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Syracuse Carthage | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Marcus Claudius Marcellus | Epicydes | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

Unknown | Unknown

| ||||||

The Siege of Syracuse by the Roman Republic took place in 213–212 BC[1], at the end of which the Magna Graecia Hellenistic city of Syracuse, located on the east coast of Sicily, fell. The Romans stormed the city after a protracted siege giving them control of the entire island of Sicily. During the siege, the city was protected by weapons developed by Archimedes. Archimedes, the great inventor and polymath, was slain at the conclusion of the siege by a Roman soldier, in contravention of the Roman proconsul Marcellus' instructions to spare his life.[2]

Contents

1 Prelude

2 Siege

3 Stalemate

4 Victory

5 Aftermath

6 In popular culture

7 Citations

8 Bibliography

9 External links

Prelude

Hiero II of Syracuse calls Archimedes to fortify the city by Sebastiano Ricci (1720s).

Sicily, which was wrested from Carthaginian control during the First Punic War (264–241 BC), was the first province of the Roman Republic not directly part of Italy. The Kingdom of Syracuse was an allied independent region in the south east of the island and a close ally of Rome during the long reign of King Hiero II.[3] In 215 BC, Hiero's grandson, Hieronymus, came to the throne on his grandfather's death and Syracuse fell under the influence of an anti-Roman faction, including two of his uncles, amongst the Syracusan elite. Despite the assassination of Hieronymus and the removal of the pro-Carthaginian leaders, Rome's threatening reaction to the danger of a Syracusian alliance with Carthage would force the new republican leaders of Syracuse to prepare for war.

Despite diplomatic attempts, war broke out between the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Syracuse in 214 BC, while the Romans were still busy battling with Carthage at the height of the Second Punic War (218–201 BC).

A Roman force led by the proconsul Marcus Claudius Marcellus consequently laid siege to the port city by sea and land in 213 BC. The city of Syracuse, located on the eastern coast of Sicily was renowned for its significant fortifications, great walls that protected the city from attack. Among the Syracuse defenders was the mathematician and scientist Archimedes.

Siege

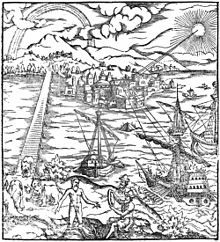

Detail of a wall painting of the Claw of Archimedes sinking a ship (c. 1600).

The city was fiercely defended for many months against all the measures the Romans could bring to bear. Realizing how difficult the siege would be, the Romans brought their own unique devices and inventions to aid their assault. These included the sambuca, a floating siege tower with grappling hooks, as well as ship-mounted scaling ladders that were lowered with pulleys onto the city walls.

Despite these novel inventions, Archimedes devised defensive devices to counter the Roman efforts including a huge crane operated hook – the Claw of Archimedes – that was used to lift the enemy ships out of the sea before dropping them to their doom. Legend has it that he also created a giant mirror (see heat ray) that was used to deflect the powerful Mediterranean sun onto the ships' sails, setting fire to them. These measures, along with the fire from ballistas and onagers mounted on the city walls, frustrated the Romans and forced them to attempt costly direct assaults.

Stalemate

Archimedes sets on fire the Roman ships before Syracuse with the help of parabolic mirrors.

The siege bogged down to a stalemate with the Romans unable to force their way into the city or keep their blockade tight enough to stop supplies reaching the defenders, and the Syracusians unable to force the Romans to withdraw.

The Carthaginians realised the potential hindrance a continuing Syracusian defense could cause to the Roman war effort and attempted to relieve the city from the besiegers but were driven back. Though they planned another attempt, they could not afford the necessary troops and ships with the ongoing war against the Romans in Hispania, and the Syracusians were on their own.

Victory

The successes of the Syracusians in repelling the Roman siege had made them overconfident. In 212 BC, the Romans received information that the city's inhabitants were to participate in the annual festival to their goddess Artemis. A small party of Roman soldiers approached the city under the cover of night and managed to scale the walls to get into the outer city and with reinforcements soon took control, but the main fortress remained firm.

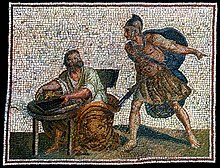

Archimedes before his death with the Roman soldier – copy of a Roman mosaic from the 2nd century.

Marcus Claudius Marcellus had ordered that Archimedes, the well-known mathematician – and possibly equally well-known to Marcellus as the inventor of the mechanical devices that had so dominated the siege – should not be killed. Archimedes, who was now around 78 years of age, continued his studies after the breach by the Romans and while at home, his work was disturbed by a Roman soldier. Archimedes protested at this interruption of his work and coarsely told the soldier to leave; the soldier, not knowing who he was (or perhaps aware of his identity as the designer of war machines that had killed hundreds of Romans), killed Archimedes on the spot.[4]

The Romans now controlled the outer city but the remainder of the population of Syracuse had quickly fallen back to the fortified inner citadel, offering continued resistance. The Romans now put siege to the citadel and were successful in cutting off supplies to this reduced area. After a lengthy eight-month siege which brought great hardship onto the defenders through hunger, and with parleys in progress, an Iberian captain named Moeriscus, one of the three prefects of Achradina, decided to save his own life by letting the Romans in near the Fountains of Arethusa. On the agreed signal, during a diversionary attack, he opened the gate. After setting guards on the houses of the pro-Roman faction, Marcellus gave Syracuse to plunder.[5] Frustrated and angered after the lengthy and costly siege, the Romans rampaged through the citadel and slaughtered many of the Syracusians where they stood and enslaved most of the rest. The city was then thoroughly looted and sacked.

Aftermath

The city of Syracuse was now under the influence of Rome again, which united the whole of Sicily as a Roman province. The taking of Syracuse ensured that the Carthaginians could not get a foothold in Sicily, which could have led to them giving support to Hannibal's Italian campaign, and this allowed the Romans to concentrate on waging the war in Spain and Italy. The island was used as a vital gathering point for the final victorious campaign in Africa 10 years later and would prove to be an important step onto both Africa and Greece in coming Roman conflicts.

Syracuse was later extensively rebuilt and repopulated and would be an important city for the Roman empire until well into the 5th century, playing both a military and economic part in the creation of the empire.

In popular culture

- Archimedes and the Siege of Syracuse are dramatically reenacted in the classic early Italian silent film Cabiria (1914).

- The 1960 film Siege of Syracuse dramatizes the events of the siege.

- The events surrounding the Siege are the basis for the manga Heureka by Hitoshi Iwaaki.

Citations

^ Hoyos 2015, p. 159.

^ Plutarch, "Life of Marcellus", Lives

^ Livy xxi. 49–51, xxii. 37, xxiii. 21

^ "Archimedes – Biography, Facts and Pictures". famousscientists.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Norman Davies, Europe: A History, page 144

Bibliography

Hoyos, Dexter (2015). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

External links

- Livius, Syracuse: History [1]

- Roman-empire.net, Capture of Syracuse [2]

- Plutarch's Life of Marcellus

Coordinates: 37°05′00″N 15°17′00″E / 37.0833°N 15.2833°E / 37.0833; 15.2833