Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram Kancheepuram, Kanchi | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

Kailasanathar temple, 685-705, the oldest temple in the city | |

| Nickname(s): Kānchi | |

Kanchipuram | |

| Coordinates: 12°49′N 79°43′E / 12.82°N 79.71°E / 12.82; 79.71Coordinates: 12°49′N 79°43′E / 12.82°N 79.71°E / 12.82; 79.71 | |

| Country | |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| Region | Tondai Nadu |

| District | Kanchipuram |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Kanchipuram Municipality |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 164,265 |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Tamil |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 631501-631503 |

| Telephone code | 044 |

| Vehicle registration | TN-21 |

| Website | kanchi.tn.nic.in |

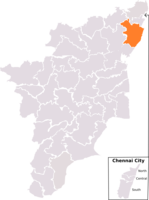

Kanchipuram,a also known as Kānchi (kāñcipuram; [kaːɲd͡ʒipuɾəm])[1] or Kancheepuram, is a city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu in Tondaimandalam region, 72 km (45 mi) from Chennai – the capital of Tamil Nadu. The city covers an area of 11.605 km2 (4.481 sq mi) and had a population of 164,265 in 2001.[2] It is the administrative headquarters of Kanchipuram District. Kanchipuram is well-connected by road and rail. Chennai International Airport is the nearest domestic and international airport to the city, which is located at Tirusulam in Kanchipuram district.

Located on the banks of the Vegavathy river, Kanchipuram has been ruled by the Pallavas, the Medieval Cholas,[3] the Later Cholas, the Later Pandyas, the Vijayanagara Empire, the Carnatic kingdom, and the British, who called the city "Conjeeveram".[3] The city's historical monuments include the Kailasanathar Temple and the Vaikunta Perumal Temple. Historically, Kanchipuram was a centre of education [4] and was known as the ghatikasthanam, or "place of learning".[5] The city was also a religious centre of advanced education for Jainism and Buddhism between the 1st and 5th centuries.[6]

In Vaishnavism Hindu theology, Kanchipuram is one of the seven Tirtha (pilgrimage) sites, for spiritual release.[7] The city houses Varadharaja Perumal Temple, Ekambareswarar Temple, Kamakshi Amman Temple, and Kumarakottam Temple which are some of major Hindu temples in the state. Of the 108 holy temples of the Hindu god Vishnu, 14 are located in Kanchipuram. The city is particularly important to Sri Vaishnavism, but is also a holy pilgrimage site in Shaivism. The city is well known for its hand woven silk sarees and most of the city's workforce is involved in the weaving industry.[8]

Kanchipuram is administered by a Special grade municipality constituted in 1947. It is the headquarters of the Kanchi matha, a Hindu monastic institution believed to have been founded by the Hindu saint and commentator Adi Sankaracharya, and was the capital city of the Pallava Kingdom between the 4th and 9th centuries.

Kanchipuram has been chosen as one of the heritage cities for HRIDAY - Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana scheme of Government of India.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

3 Geography

4 Climate

5 Government and politics

6 Demographics

7 Economy

7.1 Human rights

8 Transport, communication and utility services

9 Education

10 Religion

10.1 Buddhism

10.2 Jainism

10.3 Hinduism

10.4 Other religions

11 See also

12 Notes

12.1 Footnotes

12.2 Citations

13 References

14 External links

Etymology

Kanchipuram was known in early Tamil literature as Kachi or Kachipedu but was later Sanskritized to Kanchi or Kanchipuram.[9] In Tamil the word split into two ka and anchi. Ka means Brahma and anchi means worship, showing that Kanchi stands for the place where Lord Shiva was worshipped by Lord Brahma. In Sanskrit the term Kanci means girdle and explanation is given that the city is like a girdle to the earth.[10] The earliest inscription from the Gupta period (325–185 BCE) denote the city as Kanchipuram, where King Visnugopa was defeated by Samudragupta .[11]Patanjali (150 BCE or 2nd century BCE) refers to the city in his Mahabhasya as Kanchipuraka.[11] The city was referred to by various Tamil names like Kanchi, Kanchipedu and Sanskrit names like Kanchipuram.[9][11] The Pallava inscriptions from (250–355) and the inscriptions of the Chalukya dynasty refers the city as Kanchipura.[11]Jaina Kanchi refers to the area around Tiruparutti Kundram.[11] During the British rule, the city was known as Conjeevaram[1] and later as Kanchipuram. The municipal administration was renamed Kancheepuram, while the district retains the name Kanchipuram.[12][13]

History

Sculptures inside Kanchipuram Kailasanathar Temple – the oldest existing temple in the city

While it is widely accepted that Kanchipuram had served as an Early Chola capital,[14][15] the claim has been contested by Indian historian P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar who wrote that the Tamil culture of the Sangam period did not spread through the Kanchipuram district, and cites the Sanskritic origins of its name in support of his claim.[16] The earliest references to Kanchipuram are found in the books of the Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali, who lived between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE.[16] The city is believed to have been part of the mythical Dravida Kingdom of the Mahabharatha,[16] and was described as "the best among cities" (Sanskrit: Nagareshu Kanchi) by the 4th-century Sanskrit poet, Kalidasa.[17][dead link] The city was regarded as the "Banaras of the South".[18]

Kanchipuram grew in importance when the Pallavas of southern Andhra Pradesh, wary of constant invasions from the north, moved their capital south to the city in the 6th century.[19][20] The Pallavas fortified the city with ramparts, wide moats, well-laid-out roads, and artistic temples. During the reign of the Pallava King Mahendravarman I, the Chalukya King Pulakesin II (610–642) invaded the Pallava kingdom as far as the Kaveri River. The Pallavas successfully defended Kanchipuram and foiled repeated attempts to capture the city.[21] A second invasion ended disastrously for Pulakesin II, who was forced to retreat to his capital Vatapi which was besieged and Pulakesin II was killed by Narasimhavarman I (630–668), son of Mahendravarman I (600–630), at the Battle of Vatapi.[22][21] Under the Pallavas, Kanchipuram flourished as a centre of Hindu and Buddhist learning. King Narasimhavarman II built the city's important Hindu temples, the Kanchi Kailasanathar Temple, the Varadharaja Perumal Temple and the Iravatanesvara Temple.[23]Xuanzang, a Chinese traveller who visited Kanchipuram in 640, recorded that the city was 6 miles (9.7 km) in circumference and that its people were renowned for their bravery, piety, love of justice, and veneration for learning.[20][24]

The Medieval Chola king Aditya I conquered the Pallava kingdom, including Kanchipuram, after defeating the Pallava ruler Aparajitavarman (880–897) in about 890.[25] Under the Cholas, the city was the headquarters of the northern viceroyalty.[26] The province was renamed "Jayamkonda Cholamandalam" during the reign of King Raja Raja Chola I (985–1014),[27][28] who constructed the Karchapeswarar Temple and renovated the Kamakshi Amman Temple.[28] His son, Rajendra Chola I (1012–44) constructed the Yathothkari Perumal Temple.[29] According to the Siddhantasaravali of Trilocana Sivacharya, Rajendra Chola I brought a band of Saivas with him on his return from the Chola expedition to North India and settled them in Kanchipuram.[30] In about 1218, the Pandya king Maravarman Sundara Pandyan (1216–1238) invaded the Chola country, making deep inroads into the kingdom which was saved by the intervention of the Hoysala king Vira Narasimha II (1220–1235), who fought on the side of the Chola king Kulothunga Chola III.[31][32] Inscriptions indicate the presence of a powerful Hoysala garrison in Kanchipuram, which remained in the city until about 1230.[33]Shortly afterwards, Kanchipuram was conquered by the Telugu Cholas, from whom Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan I took the city in 1258.[34] The city remained with the Pandyas until 1311 when the Sambuvarayars declared independence, taking advantage of the anarchy caused by Malik Kafur's invasion.[27][35] After short spells of occupation by Ravivarman Kulasekhara of Venad (Quilon, Kerala) in 1313–1314 and the Kakatiya ruler Prataparudra II, Kanchipuram was conquered by the Vijayanagar general Kumara Kampana, who defeated the Madurai Sultanate in 1361.[13]

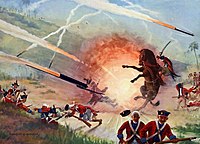

The Battle of Pollilur, fought near Kanchipuram in 1780

The Vijayanagar Empire ruled Kanchipuram from 1361 to 1645.[13] The earliest inscriptions attesting to Vijayanagar rule are those of Kumara Kampanna from 1364 and 1367, which were found in the precincts of the Kailasanathar Temple and Varadaraja Perumal Temple respectively.[13] His inscriptions record the re-institution of Hindu rituals in the Kailasanathar Temple that had been abandoned during the Muslim invasions.[13] Inscriptions of the Vijayanagar kings Harihara II, Deva Raya II, Krishna Deva Raya, Achyuta Deva Raya, Sriranga I, and Venkata II are found within the city.[13] Harihara II endowed grants in favour of the Varadaraja Perumal Temple.[13]In the 15th century, Kanchipuram was invaded by the Velama Nayaks in 1437, the Gajapati kingdom in 1463–1465 and 1474–75 and the Bahmani Sultanate in about 1480.[13] A 1467 inscription of Virupaksha Raya II mentions a cantonment in the vicinity of Kanchipuram.[13] In 1486, Saluva Narasimha Deva Raya, the governor of the Kanchipuram region, overthrew the Sangama Dynasty of Vijayanagar and founded the Saluva Dynasty.[13] Like most of his predecessors, Narasimha donated generously to the Varadaraja Perumal Temple.[13] Kanchipuram was visited twice by the Vijayanagar king Krishna Deva Raya, considered to be the greatest of the Vijayanagar rulers, and 16 inscriptions of his time are found in the Varadaraja Perumal Temple.[13] The inscriptions in four languages – Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Sanskrit – record the genealogy of the Tuluva kings and their contributions, along with those of their nobles, towards the upkeep of the shrine.[13] His successor, Achyuta Deva Raya, reportedly had himself weighed against pearls in Kanchipuram and distributed the pearls amongst the poor.[13] Throughout the second half of the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries, the Aravidu Dynasty tried to maintain a semblance of authority in the southern parts after losing their northern territories in the Battle of Talikota.[13]Venkata II (1586–1614) tried to revive the Vijayanagar Empire, but the kingdom relapsed into confusion after his death and rapidly fell apart after the Vijayanagar king Sriranga III's defeat by the Golconda and Bijapur sultanates in 1646.[13]

After the fall of the Vijayanagar Empire, Kanchipuram endured over two decades of political turmoil.[13] The Golconda Sultanate gained control of the city in 1672, but lost it to Bijapur three years later.[13] In 1676, Shivaji arrived in Kanchipuram at the invitation of the Golconda Sultanate in order to drive out the Bijapur forces.[13] His campaign was successful and Kanchipuram was held by the Golconda Sultanate until its conquest by the Mughal Empire led by Aurangazeb in October 1687.[13]In the course of their southern campaign, the Mughals defeated the Marathas under Sambhaji, the elder son of Shivaji, in a battle near Kanchipuram in 1688[13] which caused considerable damage to the city but cemented Mughal rule. [13]Soon after, the priests at the Varadaraja Perumal, Ekambareshwarar and Kamakshi Amman temples, mindful of Aurangazeb's reputation for iconoclasm, transported the idols to southern Tamil Nadu and did not restore them until after Aurangazeb's death in 1707.[13] Under the Mughals, Kanchipuram was part of the viceroyalty of the Carnatic which, in the early 1700s, began to function independently, retaining only a nominal acknowledgement of Mughal rule.[13] The Marathas invaded Kanchipuram during the Carnatic period in 1724 and 1740, and the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1742.[36]

Kanchipuram was a battlefront for the British East India Company in the Carnatic Wars against the French East India Company and in the Anglo-Mysore Wars with the Sultanate of Mysore.[37]The popular 1780 Battle of Pollilur of the Second Anglo-Mysore War, known for the use of rockets by Hyder Ali of Mysore, was fought in the village of Pullalur near Kanchipuram.[38] In 1763, the British East India Company assumed indirect control from the Nawab of the Carnatic over the erstwhile Chingleput District, comprising the present-day Kanchipuram and Tiruvallur districts, in order to defray the expenses of the Carnatic wars.[13] The Company brought the territory under their direct control during the Second Anglo-Mysore War, and the Collectorate of Chingleput was created in 1794.[13] The district was split into two in 1997 and Kanchipuram made the capital of the newly created Kanchipuram district.[13]

Geography

Kanchipuram is located at 12°59′N 79°43′E / 12.98°N 79.71°E / 12.98; 79.71, 72 km (45 mi) south-west of Chennai on the banks of the Vegavathi River, a tributary of the Palar River.[39] The city covers an area of 11.6 km2 (4.5 sq mi) and has an elevation of 83.2 m (273 ft) above sea level.[39]The land around Kanchipuram is flat and slopes towards the south[39] and east.[40] The soil in the region is mostly clay,[40] with some loam, clay, and sand, which are suitable for use in construction.[39] The Chingleput District Manual (1879) describes the region's soils as "highly inferior" and "highly stony or mixed with lime, gravel, soda and laterite".[41] It has been postulated that the granite required for the Varadaraja Perumal Temple might have been obtained from the Sivaram Hills located 10 miles east of Kanchipuram.[40] The area is classified as a Seismic Zone II region,[42] and earthquakes of up to magnitude 6 on the Richter Scale may be expected.[43] Kanchipuram is subdivided into two divisions – Big Kanchi, also called Shiva Kanchi occupies the western portion of the city and is the larger of the two divisions. Little Kanchi, also called Vishnu Kanchi, is located on the eastern fringes of the city.[40][44] Most of the Shiva temples lie in Big Kanchi while most of the Vishnu temples lie in Little Kanchi.[40]

Ground water is the major source of water supplies used for irrigation – the block of Kanchipuram has 24 canals, 2809 tanks, 1878 tube wells and 3206 ordinary wells.[45] The area is rich in medicinal plants, and historic inscriptions mention the medicinal value.[46] Dimeria acutipes and cyondon barberi are plants found only in Kanchipuram and Chennai.[47]

Climate

The Climate of Kanchipuram is generally healthy. [48] Temperatures reache an average maximum of 37.5 °C (99.5 °F) between April and July, and an average minimum of 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) between December and February.[48][48] Relative humidities of between 58% and 84% prevail throughout the year.[48] The humidity reaches its peak during the morning and is lowest in the evening. Relative humidity is higher between November and January and is lowest throughout June.[48]

The city receives an average of 1400 mm of rainfall annually, 68% of which falls during the northeast monsoon.[39] Most of the precipitation occurs in the form of cyclonic storms caused by depressions in the Bay of Bengal during the northeast monsoon.[48] Kanchipuram receives rainfall from both Northeast Monsoon and Southwest Monsoon.The highest Single day rainfall recorded in Kanchipuram is 450mm On October 10,1943. The prevailing wind direction is south-westerly in the morning and south-easterly in the evening. In 2015, Kanchipuram district registered the heaviest rainfall of 182cm in tamilnadu. On 13.11.2015 Kanchipuram recorded a mammoth of 340mm thereby causing Severe flooding. In 2017, Kanchipuram recorded more than 100cm of rain during Southwest Monsoon.[49]

| Climate data for Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.1 (84.4) | 31.2 (88.2) | 33.4 (92.1) | 35.6 (96.1) | 38.2 (100.8) | 37.2 (99) | 35.2 (95.4) | 34.7 (94.5) | 34.1 (93.4) | 32.1 (89.8) | 29.3 (84.7) | 28.5 (83.3) | 33.2 (91.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.2 (66.6) | 19.8 (67.6) | 22.0 (71.6) | 25.4 (77.7) | 27.3 (81.1) | 27.0 (80.6) | 25.9 (78.6) | 25.4 (77.7) | 24.8 (76.6) | 23.7 (74.7) | 21.6 (70.9) | 19.9 (67.8) | 23.5 (74.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 25 (1) | 6 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | 19 (0.7) | 59 (2.3) | 150 (5.9) | 190 (7.5) | 200 (7.9) | 156 (6.1) | 230 (9.1) | 254 (10) | 107 (4.2) | 1,400 (55.1) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[50] | |||||||||||||

Government and politics

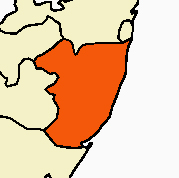

Kanchipuram Loksabha constituency

Municipality Officials | |

|---|---|

| Chairman | T. Mythili.[51] |

| Commissioner | N. Vimala[52] |

| Vice-Chairman | R.T. Sekar[53] |

Elected Members | |

| Member of Legislative Assembly | C.V.M.P.Ezhilarasan[54] |

| Member of Parliament | K. Maragatham[55] |

The Kanchipuram municipality was officially constituted in 1866,[20] covering 7.68 km2 (2.97 sq mi), and its affairs were administered by a municipal committee. It was upgraded to a grade I municipality in 1947, selection grade municipality in 1983 and special grade municipality in 2008.[56][12] As of 2011[update] the municipality occupies 11.6 km2 (4.5 sq mi), has 51 wards and is the biggest municipality in Kanchipuram district.[12] The functions of the municipality are devolved into six departments: General, Engineering, Revenue, Public Health, city Planning and the Computer Wing,[57] all of which are under the control of a Municipal Commissioner, who is the supreme executive head.[57] The legislative powers are vested in a body of 51 members, each representing one ward. The legislative body is headed by an elected Chairperson who is assisted by a Deputy Chairperson.[58]

Kanchipuram comes under the Kanchipuram state assembly constituency. From the state delimitation after 1967, seven of the ten elections held between 1971 and 2011 were won by the Anna Dravida Muneetra Kazhagam (ADMK).[59]Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) won the seat during the 1971 and 1989 elections and its ally Pattali Makkal Katchi won the seat during the 2006 elections.[59] The current member of the legislative assembly is V. Somasundaram from the ADMK party.[59][54]

Kanchipuram Lok Sabha constituency is a newly formed constituency of the Parliament of India after the 2008 delimitation.[60] The constituency originally existed for the 1951 election, and was formed in 2008 after merging the assembly segments of Chengalpattu, Thiruporur, Madurantakam (SC), Uthiramerur and Kanchipuram, which were part of the now defunct Chengalpattu constituency, and Alandur, which was part of the Chennai South constituency. This constituency is reserved for Scheduled Castes (SC) candidates. K. Maragatham from the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam is the current Member of Parliament for the constituency.[55] Indian writer, politician and founder of the DMK, C. N. Annadurai, was born and raised in Kanchipuram.[61] He was the first member of a Dravidian party to hold that post and was the first non-Congress leader to form a majority government in post-colonial India.[62][63]

Policing in the city is provided by the Kanchipuram sub-division of the Tamil Nadu Police headed by a Deputy Superintendent of Police.[64] The force's special units include prohibition enforcement, district crime, social justice and human rights, district crime records and special branch that operate at the district level police division, which is headed by a Superintendent of Police.[64]

Demographics

A house depicting old living style of Kanchipuram

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1871 | 37,275 | — |

| 1881 | 37,312 | +0.1% |

| 1891 | 42,547 | +14.0% |

| 1901 | 46,164 | +8.5% |

| 1911 | 53,864 | +16.7% |

| 1921 | 61,376 | +13.9% |

| 1931 | 65,258 | +6.3% |

| 1941 | 74,685 | +14.4% |

| 1951 | 84,810 | +13.6% |

| 1961 | 92,714 | +9.3% |

| 1971 | 110,657 | +19.4% |

| 1981 | 131,013 | +18.4% |

| 1991 | 144,955 | +10.6% |

| 2001 | 153,140 | +5.6% |

| 2011 | 164,265 | +7.3% |

Sources:

| ||

During the rule of King Narasimha Varma in the 7th century, the city covered about 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi) and had a population of 10,000.[68] The population increased to 13,000 in subsequent years and the city developed cross patterned links with rectangular streets.[69] The settlements in the city were mostly caste based.[69] During the period of Nandivarma Pallavan II, houses were built on raised platforms and burnt bricks.[69] The concepts of the verandah in the front yard, garden in the backyard, ventilation facilities and drainage of rainwater were all introduced for the first time.[69] The centre of the city was occupied by Brahmins, while the Tiruvekka temple and houses of agricultural labourers were situated outside the city.[70] There were provisions in the city's outskirts for training the cavalry and infantry.[70]

During the Chola era, Kanchipuram was not the capital, but the kings had a palace in the city and lot of development was extended eastwards.[69] During the Vijayanagara period, the population rose to 25,000.[69] There were no notable additions to the city's infrastructure during British rule.[69] The British census of 1901 recorded that Kanchipuram had a population of 46,164, consisting of 44,684 Hindus, 1,313 Muslims, 49 Christians and 118 Jains.[20]

According to 2011 census, Kanchipuram had a population of 164,384 with a sex-ratio of 1,005 females for every 1,000 males, much above the national average of 929.[71] A total of 15,955 were under the age of six, constituting 8,158 males and 7,797 females. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes accounted for 3.55% and .09% of the population respectively. The average literacy of the city was 79.51%, compared to the national average of 72.99%.[71] The city had a total of 41807 households. There were a total of 61,567 workers, comprising 320 cultivators, 317 main agricultural labourers, 8,865 in house hold industries, 47,608 other workers, 4,457 marginal workers, 61 marginal cultivators, 79 marginal agricultural labourers, 700 marginal workers in household industries and 3,617 other marginal workers.[72][67] About 800,000 (800,000) pilgrims visit the city every year as of 2001.[73] As per the religious census of 2011, Kancheepuram had 93.38% Hindus, 5.24% Muslims, 0.83% Christians, 0.01% Sikhs, 0.01% Buddhists, 0.4% Jains, 0.11% following other religions and 0.01% following no religion or did not indicate any religious preference.[74]

Kanchipuram has 416 hectares (1,030 acres) of residential properties, mostly around the temples. The commercial area covers 62 hectares (150 acres), constituting 6.58% of the city. Industrial developments occupy around 65 hectares (160 acres), where most of the handloom spinning, silk weaving, dyeing and rice production units are located. 89.06 hectares (220.1 acres) are used for transport and communications infrastructure, including bus stands, roads, streets and railways lines.[75]

Economy

Silk Saree Weaving at Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram Silk Sarees hanging

The major occupations of Kanchipuram are silk saree weaving and agriculture.[20] As of 2008, an estimated 5,000 families were involved in saree production.[76] The main industries are cotton production, light machinery and electrical goods manufacturing, and food processing.[77] There are 25 silk and cotton yarn industries, 60 dyeing units, 50 rice mills and 42 other industries in the Kanchipuram.[78] Another important occupation is tourism and service related segments like hotels, restaurants and local transportation.[78]

Agriculture in Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram is a traditional centre of silk weaving and handloom industries for producing Kanchipuram Sarees. The industry is worth ₹ 100 cr (US$18.18 million), but the weaving community suffers from poor marketing techniques and duplicate market players.[76] In 2005, "Kanchipuram Silk Sarees" received the Geographical Indication tag, the first product in India to carry this label.[79][80] The silk trade in Kanchipuram began when King Raja Raja Chola I (985–1014) invited weavers to migrate to Kanchi.[76] The craft increased with the mass migration from Andhra Pradesh in the 15th century during the Vijayanagara rule.[76] The city was razed during the French siege of 1757, but weaving re-emerged in the late 18th century.[76]

All major nationalised banks such as Vijaya Bank, State Bank of India, Indian Bank, Canara Bank, Punjab National Bank, Dena Bank and private banks like ICICI Bank have branches in Kanchipuram.[81] All these banks have their Automated teller machines located in various parts of the city.[81]

Human rights

Kanchipuram has more than the national average rate of child labour and bonded labour.[82][83] The local administration is accused of aiding child labour by opening night schools in Kanchipuram from 1999.[82] There is an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 child workers in Kanchipuram compared to 85,000 in the same industry in Varanasi.[83] Children are commonly traded for sums of between ₹ 10,000 and 15,000 (200 – $300) and there are cases where whole families are held in bondage.[83] Child labour is prohibited in India by the Children (Pledging of Labour) Act and Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, but these laws are not strictly enforced.[84]

Transport, communication and utility services

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Kanchipuram is most easily accessible by road. The Chennai – Bangalore National Highway, NH 4 passes the outskirts of the city.[85] Daily bus services are provided by the Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation to and from Chennai, Bangalore, Villupuram, Tirupathi, Thiruthani, Tiruvannamalai, Vellore, Salem, Coimbatore, Tindivanam and Pondicherry.[86] There are two major bus routes to Chennai, one connecting via Poonamallee and the other via Tambaram.[86] Local bus services are provided by The Villupuram division of Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation.[87] As of 2006, there were a total of 403 buses for 191 routes operated out of the city.[88]

The city is also connected to the railway network through the Kanchipuram railway station. The Chengalpet – Arakkonam railway line passes through Kanchipuram and travellers can access services to those destinations.[89] Daily trains are provided to Pondicherry and Tirupati, and there is a weekly express train to Madurai and a bi-weekly express train to Nagercoil.[90] Two passenger trains from both sides of Chengalpattu and Arakkonam pass via Kanchipuram.[86][90]

The nearest domestic as well as international airport is Chennai International Airport, located at a distance of 72 km from the city

Telephone and broadband internet services are provided by Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL), India's state-owned telecom and internet services provider.[91] Electricity supply is regulated and distributed by the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board (TNEB).[92] Water supply is provided by the Kanchipuram municipality; supplies are drawn from subterranean springs of Vegavati river.[20] The head works is located at Orikkai, Thiruparkadal and St. Vegavathy, and distributed through overhead tanks with a total capacity of 9.8 litres (2.2 imperial gallons).[93] About 55 tonnes of solid waste are collected from the city daily at five collection points covering the whole of the city.[94] The sewage system in the city was implemented in 1975; Kanchipuram was identified as one of the hyper endemic cities in 1970. Underground drainage covers 82% of roads in the city, and is divided into east and west zones for internal administration.[95]

Education

Kanchipuram is traditionally a centre of religious education for the Hindu,[4][5] Jainism[6]

and Buddhism faiths.[6] The Buddhist monasteries acted as nucleus of the Buddhist educational system. With the gradual resurrection of Hinduism during the reign of Mahendra Varman I, the Hindu educational system gained prominence with Sanskrit emerging as the official language.[6]

As of 2011[update] Kanchipuram has 49 registered schools, 16 of which are run by the city municipality.[96] The district administration opened night schools for educating children employed in the silk weaving industry – as of December 2001, these schools together were educating 127 people and 260 registered students from September 1999.[82]Larsen & Toubro inaugurated the first rail construction training centre in India at Kanchipuram on 24 May 2012, that can train 300 technicians and 180 middle level managers and engineers each year.[97] Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Mahavidyalaya and Chettinad Academy of Research and Education (CARE) are the two Deemed universities present in Kanchipuram.[98]

Kanchipuram is home to one of the four Indian Institute of Information of Technology, a public private partnered institute, offering under graduate and post graduate programs in information technology.[99] The city has two medical colleges – Arignar Anna Memorial Cancer Institute and Hospital, established in 1969 is operated by the Department of Health, Government of Tamil Nadu [100] and the privately owned Meenakshi Medical College.[101] The city has 6 engineering colleges,[102] 3 polytechnic institutes and 6 arts and science colleges.[103]

Religion

Buddhism

Bodhidharma is believed to have spread Zen school of Buddhism from India to China

Buddhism is believed to have flourished in Kanchipuram between the 1st and 5th centuries.[104] Some notable Buddhists associated with Kanchipuram are Āryadeva (2nd–3rd centuries) – a successor of Nāgārjuna of Nalanda University, Dignaga and the Pali commentators Buddhaghosa and Dhammapala.[105] According to a popular tradition, Bodhidharma, a 5th/6th-century Buddhist monk and founder of Shaolin Kung Fu was the third son of a Pallava king from Kanchipuram.[106] However, other traditions ascribe his origins to other places in Asia.[107]Buddhists institutions from Kanchipuram were instrumental in spreading Theravada Buddhism to the Mon people of Myanmar and Thailand who in return spread the religion to the incoming Burmese and Thai people.[108]

A number of bronzes unearthed at Kurkihar (Apanaka Vihara, near Gaya in Bihar) mention that the majority of the donors were from Kanchi, indicating that Kurkihar was a major center for the visitors from Kanchi during 9th to 11th century,

Jainism

Trilokyanatha Temple

It is thought that Jainism was introduced into Kanchipuram by Kunda Kundacharya (1st century).[105] Jainism spread to the city by Akalanka (3rd century). Kalbhras, the rulers of Kanchipuram before the Pallavas, followed Jainism which gained popularity from royal patronage.[105] The Pallava kings, Simhavishnu, Mahendra Varman and Simhavarman (550–560) followed Jainism, until the advent of Nayanmars and Azhwars during the 6th and 7th centuries.[105]Mahendravarman I converted from Jainism to Hinduism under the influence of the Naynamar, Appar, was the turning point in the religious geography.[105] The two sects of Hinduism, Saivism and Vaishnavism were revived under the influence of Adi Sankara and Ramanuja respectively.[70][109] Later Cholas and Vijayanagara kings tolerated Jainism, and the religion was still practised in Kanchi.[105]

Trilokyanatha/Chandraprabha temple is a twin Jain temple that has inscriptions from Pallava king, Narasimhavarman II and the Chola kings Rajendra Chola I, Kulothunga Chola I and Vikrama Chola, and the Kanarese inscriptions of Krishnadevaraya. The temple is maintained by Tamil Nadu archaeological department.[110]

Hinduism

Ekambareswarar temple – the largest temple in the city

Hindus regard Kanchipuram to be one of the seven holiest cities in India, the Sapta Puri.[18][111] According to Hinduism, a kṣetra is a sacred ground, a field of active power, and a place where final attainment, or moksha, can be obtained. The Garuda Purana says that seven cities, including Kanchipuram are providers of moksha.[70] The city is a pilgrimage site for both Saivites and Vaishnavites.[70] It has close to 108 Shiva temples.[112]

Ekambareswarar Temple in northern Kanchipuram, dedicated to Shiva, is the largest temple in the city.[113] Its gateway tower, or gopuram, is 59 metres (194 ft) tall, making it one the tallest temple towers in India. The temple is one of five called Pancha Bhoota Stalams, which represent the manifestation of the five prime elements of nature; land, water, air, sky, and fire.[114] Ekambareswarar temple represents earth.[114]

Kailasanathar Temple, dedicated to Shiva and built by the Pallavas, is the oldest Hindu temple in existence and is declared an archaeological monument by the Archaeological Survey of India. It has a series of cells with sculptures inside.[115] In the Kamakshi Amman Temple, goddess Parvati is depicted in the form of a yantra, Chakra or peetam (basement). In this temple, the yantra is placed in front of the deity.[116] Adi Sankara is closely associated with this temple and is believed to have established the Kanchi matha after this temple.[117]

Muktheeswarar Temple, built by Nandivarman Pallava II (720–796)[118] and Iravatanesvara Temple built by Narasimhavarman Pallava II (720–728) are the other Shiva temples from the Pallava period. Kachi Metrali – Karchapeswarar Temple,[115] Onakanthan Tali,[118] Kachi Anekatangapadam,[118] Kuranganilmuttam,[119] and Karaithirunathar Temple in Tirukalimedu are the Shiva temples in the city reverred in Tevaram, the Tamil Saiva canonical work of the 7th–8th centuries.

Sculpted pillars and stone chain in Varadharaja Perumal Temple

Kumarakottam Temple, dedicated to Muruga, is located between the Ekambareswarar temple and Kamakshi Amman temple, leading to the cult of Somaskanda (Skanda, the child between Shiva and Parvati). Kandapuranam, the Tamil religious work on Muruga, translated from Sanskrit Skandapurana, was composed in 1625 by Kachiappa Shivacharya in the temple.[120]

Varadharaja Perumal Temple, dedicated to Vishnu and covering 23 acres (93,000 m2), is the largest Vishnu temple in Kanchipuram. It was built by the Cholas in 1053 and was expanded during the reigns of Kulottunga Chola I (1079–1120) and Vikrama Chola (1118–1135). It is one of the divyadesams, the 108 holy abodes of Vishnu.[121] The temple features carved lizards, one platted with gold and another with silver, over the sanctum.[122]Clive of India is said to have presented an emerald necklace to the temple. It is called the Clive Makarakandi and is still used to decorate the deity on ceremonial occasions.[13]

Tiru Parameswara Vinnagaram is the birthplace of the azhwar saint, Poigai Alvar.[123] The central shrine has a three-tier shrine, one over the other, with Vishnu depicted in each of them.[123] The corridor around the sanctum has a series of sculptures depicting the Pallava rule and conquest.[123] It is the oldest Vishnu temple in the city and was built by the Pallava king Paramesvaravarman II (728–731).[123]

Ashtabujakaram, Tiruvekkaa, Tiruththanka, Tiruvelukkai, Ulagalantha Perumal Temple, Tiru pavla vannam, Pandava Thoothar Perumal Temple are among the divyadesam, the 108 famous temples of Vishnu in the city.[124] There are a five other divyadesams, three inside the Ulagalantha Perumal temple, one each in Kamakshi Amman Temple and Ekambareswarar Temple.[125]

The Kanchi Matha is a Hindu monastic institution, whose official history states that it was founded by Adi Sankara of Kaladi, tracing its history back to the 5th century BCE.[126][127][128] A related claim is that Adi Sankara came to Kanchipuram, and that he established the Kanchi mutt named "Dakshina Moolamnaya Sarvagnya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetam" in a position of supremacy, namely Sarvagnya Peetha, over the other mathas (religious institutions) of the subcontinent, before his death there.[128][129] Other historical accounts state that the mutt was established probably in the 18th century in Kumbakonam, as a branch of the Sringeri Matha, and that it declared itself independent.[127]

Another mutt which was famous in ancient times was the Upanishad Bramham Mutt, located near Kailasanathar temple, Kanchipuram. It has the Mahasamadhi of Upanishad Brahmayogin, a saint who wrote commentaries on all the major upanishads in Hinduism. It is said that the great Sage, Sadasiva Brahmendra took to sanyasa at this mutt.

Other religions

The city has two mosques; one near the Ekambareswarar temple was built during the rule of Nawab of Arcot in the 17th century, and another near the Vaikunta Perumal temple shares a common tank with the Hindu temple. Muslims take part in the festivals of the Varadarajaswamy temple.[130] Christ Church is the oldest Christian church in the city. It was built by a British man named Mclean in 1921. The church is built in Scottish style brick structure with arches and pillars.[130]

See also

- Murugan Temple, Saluvankuppam

Notes

Footnotes

^ The official spelling, as per the municipality website, is "Kancheepuram". However, the spelling Kanchipuram is the most widely used name.

Citations

^ ab Malalasekera 1973, pp. 112–13.

^ ab Kanchipuram : Census 2011.

^ ab Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Conjeeveram". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 943..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Conjeeveram". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 943..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Rao 2008, p. xviii.

^ ab K.V. 1975, p. 80.

^ abcd Thapar 2001, pp. 344–345.

^ Jean Holm; John Bowker (2001). Sacred Place. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-62356-623-4.

^ Kanchipuram Industrial profile 2012.

^ ab K.V. 1975, p. 6.

^ http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/39511/7/07_chapter%202.pdf p.no 7

^ abcde Sharma 1978, p. 255.

^ abc About municipality 2011.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaab K.V. 1975, pp. 26–39.

^ Kamath 2000, p. 127.

^ Hoiberg 2000.

^ abc Iyengar 1929, pp. 322–333.

^ Historical Importance of Kanchipuram 2011.

^ ab Gopal 1990, p. 177.

^ Pochhammer 2005, p. 99.

^ abcdef Imperial Gazetteer of India 1908, pp. 544–546.

^ ab Keay 2001, p. 170.

^ Sastri 2008, p. 136.

^ Jouveau-Dubreuil 1994, p. 71.

^ Smith 1914, p. 473.

^ Sastri 1935, p. 113.

^ Aiyangar 2004, p. 60.

^ ab K.V. 1975, pp. 11–26.

^ ab Rao 2008, p. 126.

^ Rao 2008, p. 127.

^ Sastri 1935, p. 210.

^ Sastri 1935, p. 420.

^ Aiyangar 2004, p. 34.

^ Sastri 1935, p. 428.

^ Aiyangar 2004, p. 49.

^ Aiyangar 2004, p. 61.

^ K.V. 1975, p. 48.

^ Jaques 2007, p. 257.

^ R.G. 2011, p. 468.

^ abcde About City 2011.

^ abcde K.V. 1975, pp. 1–4.

^ Srinivasan 1979, p. 6.

^ Seismic Zoning map 2008.

^ Seismology glossary 2008.

^ Browne 1843, p. 228.

^ Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India 2007, p. 5.

^ The Hindu & 19 May 2012.

^ The Hindu & 18 June 2012.

^ abcdef Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India 2007, p. 6.

^ Kanchipuram local plan 2006, p. 1.

^ "CLIMATE: KANCHEEPURAM". Retrieved 19 February 2016.

^ Kanchipuram Municipality – Chairman 2011.

^ Kanchipuram Municipality – Commissioner 2011.

^ Vice-Chairman of Kanchipuram municipality 2011.

^ ab MLA of Kanchipuram 2011.

^ ab MP of Kanchipuram 2014.

^ List of municipalities in Tamil Nadu 2011.

^ ab Commissionerate of Municipal Administration 2011.

^ Economic and political weekly 1995, p. 2396.

^ abc Election Report – Full Statistical Report 2011.

^ rediff & 7 May 2009.

^ Kannan 2010, p. 5.

^ Frontline & 23 April 2004.

^ Chakrabarty 2008, pp. 110–111.

^ ab Kanchipuram district police 2011.

^ Hunter 1885.

^ Kanchipuram Master Plan 2001.

^ ab Kanchipuram population 2012.

^ Rao 2008, p. 142.

^ abcdefg Rao 2008, p. 143.

^ abcde Ayyar 1991, p. 69.

^ ab National Sex Ratio 2011.

^ Kanchipuram 2011 census.

^ Rao 2008, p. 145.

^ Population by religion 2013.

^ Kanchipuram local plan 2006, pp. 7–9.

^ abcde Rao 2008, pp. 134–135.

^ Husain 2011, p. 11.K.4.

^ ab Industries in Kanchipuram 2011.

^ The Economic Times & 27 December 2011.

^ The Times of India & 29 August 2010.

^ ab Kanchipuram City Banks 2011.

^ abc Human Rights Watch 2003, p. 62.

^ abc Human Rights Watch/Asia 1995, p. 82.

^ Human Rights Watch/Asia 1995, p. 88.

^ Rao 2008, p. 3.

^ abc Bus routes, Train schedules, Air schedules 2011.

^ TNSTC Villupuram 2011.

^ Kanchipuram local plan 2006, p. 10.

^ Rao 2008, p. 4.

^ ab Train Running Information 2012.

^ BSNL 2011.

^ TNEB region details 2011.

^ Kanchipuram water supply 2011.

^ Waste management programme 2011.

^ Kanchipuram sewage and sanitation 2011.

^ Educational institutes of Kanchipuram 2011.

^ The Businessline & 24 May 2012.

^ Deemed University list 2012.

^ The Indian Express & 29 May 2012.

^ TN Health Department – Arignar Anna Memorial Cancer Institute and Hospital 2012.

^ Meeenakshi Medical College and Research Institute 2012.

^ AICTE list of approved institutes 2012.

^ University of Madras – affiliated colleges 2012.

^ Trainor 2001, p. 13.

^ abcdef Rao 2008, p. 20.

^ Zvelebil 1987, p. 125-126.

^ McRae 2000, p. 26.

^ Harvey 2000, p. 56.

^ Smith 1914, p. 468.

^ The Hindu & 23 June 2011.

^ Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2007) Early Historical Setting of Kañci and its Temples. Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies 25.1: 23-52. Regd. No. 156167/85/M2. https://www.academia.edu/12190831/Early_Historical_Setting_of_Ka%C3%B1ci_and_its_Temples

^ http://www.columbuslost.com/2013/12/108-shiva-temples-of-kanchipuram.html

^ Let's Go 2004, p. 584.

^ ab Ramaswamy 2007, pp. 301–302.

^ ab Ayyar 1991, p. 73.

^ Ayyar 1991, pp. 70–71.

^ Tourist places in Kanchipuram 2012.

^ abc Ayyar 1991, p. 86.

^ Soundara Rajan 2001, p. 27.

^ Rao 2008, p. 110.

^ "Divya Desams of Lord Vishnu".

^ Gateway to Kanchipuram district – Varadaraja Temple 2011.

^ abcd Ayyar 1991, p. 80.

^ Ayyar 1991, p. 539.

^ Rao 2008, p. 109.

^ Saraswati 2001, p. 492.

^ ab Dalal 2006, p. 186.

^ ab Kuttan & Arunachalam 2009, pp. 244–245.

^ Sharma 1987, pp. 44–46.

^ ab Religious places in Kanchipuram 2011.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Seismic Zoning Map (Map). India Meteorological Department. 2008. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

Seismology glossary (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

Kanchipuram local plan (2006). Kanchipuram local plan (PDF) (Report). Kancheepuram Municipality. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India (2007). District ground water brochure – Kancheepuram district (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

"Nanmangalam forest will get wall as shield". The Hindu. 18 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Medicinal garden set up near Kancheepuram". The Hindu. 19 May 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Deprived of original élan". The Hindu. 23 June 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

Dave, Kapil (29 May 2012). "Govt ropes in TCS for much-awaited IIIT project". The Indian Express. Chennai. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

T.E., Raja Simhan (24 May 2012). "L&T opens first rail construction training centre near Chennai". The Business Line. Chennai. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

"GI tag: TN trails Karnataka with 18 products". The Times of India. 29 August 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

Sangeetha Kandavel, Sanjay Vijyakumar (27 December 2011). "Government eases norms for gold-silver mix in Kanchipuram sarees". The Economic Times. Chennai. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

"Kancheepuram weavers disillusioned". rediff. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

Viswanathan, S (23 April 2004). "A history of agitational politics". Frontline, The Hindu publishing. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

"Population By Religious Community - Tamil Nadu" (XLS). Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

"Census Info 2011 Final population totals – Kanchipuram". Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

"Census Info 2011 Final population totals". Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

"Religious places in Kanchipuram". Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"University of Madras – affiliated colleges". University of Madras. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"AICTE list of approved institutes". AICTE. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Arignar Anna Memorial Cancer Institute and Hospital". Department of Health, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Meeenakshi Medical College and Research Institute". Meenakshi Medical College. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Deemed University List". University Grants Commission. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Train Running Information". Indian Railways. 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"TNSTC Villupuram". Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation. 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Educational institutes of Kanchipuram". Kanchipuram Municipality. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram district police" (PDF). Tamil Nadu Police. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram City Banks". Kanchipuram Municipality. 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"Bus routes, Train schedules, Air schedules". Kanchipuram Municipality. 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

"About City". Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Tourist places in Kanchipuram". National Informatics centre. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Historical Importance of Kanchipuram". National Informatics centre. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram population". Kanchipuram municipality. 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

"Region Details". Tamil Nadu Electricity Board. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Solid waste management". India: Kanchipuram Municipality. 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

"Kanchipuram water supply". India: Kanchipuram Municipality. 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

"Kanchipuram sewage and sanitation". India: Kanchipuram Municipality. 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

"State of Rural wireline broadband". Tamil Nadu: BSNL, Tamil Nadu Circle. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram Industrial profile". Department of Industries and Commerce district industries centre, Kanchipuram District. 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram Municipality – Chairman". Kanchipuram Municipality, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram Municipality – Commissioner". Kanchipuram Municipality, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Vice Chairman of Kanchipuram municipality". Kanchipuram Municipality, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"MLA of Kanchipuram". Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Members of parliamentary constituencies in Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

"List of municipalities in Tamil Nadu". Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011.

"About municipality". Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Commissionerate of Municipal Administration". Commissionerate of Municipal Administration. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Election Report – Full Statistical Report". Election Commission of India. 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram : Census 2011". Population Census India (web), Ministry of Home Affairs. 2001. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Kanchipuram Master Plan" (PDF). Government of Tamil Nadu. 2001. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Industries in Kanchipuram". Kanchipuram Municipality, Government of Tamil Nadu. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

"Gateway to Kanchipuram district – Varadaraja Temple". Kanchipuram District administration. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (2004). Ancient India: Collected Essays on the Literary and Political History of. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1850-5.

Ayyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1991). South Indian shrines: illustrated. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0151-3.

Browne, Charles Alfred (1843). An introduction to the geography and history of India, and the countries. P.R. Hunt, American Mission Press.

Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2008). Indian Politics and Society Since Independence. Routledge. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-415-40868-7.

Dalal, Roshan (2006). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

Economic and political weekly (1995). Economic and political weekly, Volume 30. Sameeksha Trust. p. 2396.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2001). Tirtha: holy pilgrim centres of the Hindus : saptapuri & chaar dhaam. Rupa & Co. p. 56. ISBN 81-7167-564-6.

Kuttan, Mahadevan; Arunachalam, P.V. (2009). The Great Philosophers of India. Author House. ISBN 978-1-4343-7780-7.

Human Rights Watch (January 2003). Human Rights Watch, The small hands of slavery: Bonded Child Labour in India. hrw.org. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

Human Rights Watch/Asia (1995). Human Rights Watch, The small hands of slavery: Bonded Child Labour in India. hrw.org. ISBN 1-56432-172-X.

Husain, Majid (2011). Understanding: Geographical: Map Entries: for Civil Services Examinations. Tata McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-070288-2.

Hunter, W. W. (1885). Imperial Gazetteer of India. 6 (2 ed.). London: Trubner & Co.

Hoiberg, Indu Ramchandani (2000). Student's Britannica: India (Set of 7 Vols.) 39. 7. New Delhi: Encyclopædia Britannica (India) Private Limited. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

Imperial Gazetteer of India (1908). Madras: The presidency; mountains, lakes, rivers, canals, and historic areas – Provincial Series Madras. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

Iyengar, P. T. Srinivasa (1929). History of the Tamils from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Madras: University of Madras.

Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-33536-5.

Jouveau-Dubreuil, Tony (1994). The Pallavas. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0574-8.

Kamath, Rina (2000). Chennai. Orient Longman Limited. ISBN 81-250-1378-4.

Kannan, R. (2010). Anna: The Life and Times of C.N. Annadurai. Penguin Books India. ISBN 0-670-08328-3.

Keay, John (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

Harvey, G.E (2000). History of Burma. Asian Educational Services.

K.V., Raman (1975). Sri Varadarajaswami Temple, Kanchi: A Study of Its History, Art and Architecture. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 8170170265.

Let's Go (2004). Let's Go India & Nepal 8th Edition. NY: Let's Go Publications. ISBN 0-312-32006-X.

Malalasekera, G.P. (1973). The Pali Literature of Ceylon. Colombo: Buddhist Publication Society. pp. 112–113. ISBN 955-24-0118-6.

McRae, John R. (2000). "The Antecedents of Encounter Dialogue in Chinese Ch'an Buddhism". In Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S. The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism. Oxford University Press.

Pochhammer, Wilhelm von (2005). India's Road to Nationhood: A Political History of the Subcontinent. Mumbai: Allied Publishers (P) Ltd. ISBN 81-7764-715-6.

Rao, P.V.L. Narasimha (2008). Kanchipuram – Land of Legends, Saints & Temples. New Delhi: Readworthy Publications (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-93-5018-104-1.

R.G., Grant (2011). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of World History. United States: Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 9780789322333.

Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Historical dictionary of the Tamils. United States: Scarecrow Press, INC. ISBN 978-0-470-82958-5.

Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (2008). A History of South India (4th ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1935) [1935]. The Cōlas. Madras: University of Madras.

Saraswati, Prakashanand (2001). The True History and the Religion of India: A Concise Encyclopedia of (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1789-3.

Sharma, Varanasi Raj Gopal (1987). Kanchi Kamakoti Math, a myth. Ganga-Tunga Prakashan. ISBN 0-415-40868-7.

Sharma, Tej Ram (1978). Personal and Geographical Names in the Gupta Inscriptions. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 0-415-40868-7.

Smith, Vincent Aruthur Smith (1914). The Early History of India from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan Conquest including the invastion of Alexander the Great (3rd ed.). Clarendon Press.

Soundara Rajan, Kodayanallur Vanamamalai (2001). Concise classified dictionary of Hinduism. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7022-857-3.

Srinivasan, C. R. (1979). Kanchipuram through the ages. Agam Kala Prakashan.

Thapar, Romila (2001). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24225-4. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

Trainor, Kevin (2001). Buddhism The Illustrated Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517398-8.

Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1987). The Sound of the One Hand. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 107. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 107, No. 1. pp. 125–126. doi:10.2307/602960. JSTOR 602960.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Kanchipuram |

- Kancheepuram Municipality

- Kanchipuram HRIDAY city

- Kancheepuram district administration website

- Antique print of Hindu Temple At Conjeveram in 1890

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kanchipuram. |