Arawak

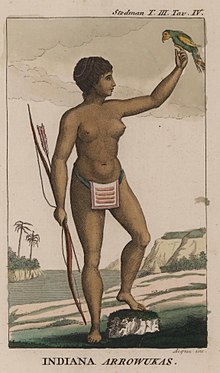

Arawak woman, by John Gabriel Stedman | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

South America, Caribbean | |

| Languages | |

Arawak, Arawakan languages, Ahuaco, Taino, Caribbean English, Caribbean Spanish | |

| Religion | |

Indigenous, Christianity |

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of South America and historically of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Greater Antilles and northern Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. All these groups spoke related Arawakan languages.

Contents

1 Name

2 History

3 Modern population and descendants

4 Notable Arawak

5 See also

6 References

7 Bibliography

Name

Arawak village (1860).

The term Arawak originally was applied by Europeans specifically to the South American group who self-identified as Arawak, Arhuaco or Lokono. Their Arawak language is the name of the overall Arawakan language family. Arawakan speakers in the Caribbean were also historically known as the Taíno, a term meaning "relatives". The Spanish assumed some islanders used this term to distinguish their group from the neighboring Island Caribs. In 1871, ethnologist Daniel Garrison Brinton proposed calling the Caribbean populace "Island Arawak" due to their cultural and linguistic similarities with the mainland Arawak. Subsequent scholars shortened this convention to "Arawak", creating confusion between the island and mainland groups. In the 20th century, scholars such as Irving Rouse resumed using "Taíno" for the Caribbean group to emphasize their distinct culture and language.[1]

History

Arawakan languages in South America. The northern Arawakan languages are colored in light blue, while the southern Arawakan languages are colored in dark blue.

The Arawakan languages may have emerged in the Orinoco River valley. They subsequently spread widely, becoming by far the most extensive language family in South America at the time of European contact, with speakers located in various areas along the Orinoco and Amazonian rivers and their tributaries.[2] The group that self-identified as the Arawak, also known as the Lokono, settled the coastal areas of what is now Guyana, Suriname, Grenada, and parts of the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.[1][3]

Michael Heckenberger, an anthropologist at the University of Florida who helped found the Central Amazon Project, and his team found elaborate pottery, ringed villages, raised fields, large mounds, and evidence for regional trade networks that are all indicators of a complex culture. There is also evidence that they modified the soil using various techniques such as deliberate burning of vegetation to transform it into black earth, which even today is famed for its agricultural productivity. According to Heckenberger, pottery and other cultural traits show these people belonged to the Arawakan language family, a group that included the Tainos, the first Native Americans Columbus encountered* It was the largest language group that ever existed in the pre-Columbian Americas.[4]

At some point, the Arawakan-speaking Taíno culture emerged in the Caribbean. Two major models have been presented to account for the arrival of Taíno ancestors in the islands; the "Circum-Caribbean" model suggests an origin in the Colombian Andes connected to the Arhuaco people, while the Amazonian model supports an origin in the Amazon basin, where the Arawakan languages developed.[5] The Taíno were among the first American people to encounter Spanish Conquistadors when Christopher Columbus visited multiple islands and chiefdoms on his first voyage in 1492, which was followed in 1493 by the establishment of La Navidad[6] on Hispaniola, the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Americas. Relationships between the Spaniards and the Taino would ultimately take a sour turn. Some of the lower-level chiefs of the Taino appeared to have assigned a supernatural origin to the explorers. The Taino believed that the explorers were mythical beings associated with the underworld who consumed human flesh. Thus, the Taino would go on to burn down La Navidad and kill 39 men[7]. There is evidence as to the taking of human trophies and the ritual cannibalism of war captives among both Arawak and other Amerindian groups such as the Carib and Tupinamba.[8]

With the establishment of La Isabella, and the discovery of gold deposits on the island, the Spanish settler population on Hispaniola started to grow substantially, while disease and conflict with the Spanish began to kill tens of thousands of Taíno every year. By 1504, the Spanish had overthrown the last of the Taíno cacique chiefdoms on Hispaniola, and firmly established the supreme authority of the Spanish colonists over the now-subjugated Taíno. Over the next decade, the Spanish Colonists commenced a brutal genocide against the remaining Taíno on Hispaniola, who suffered poor living conditions, disease, massacres, rapes, and enslavement at the hands of the colonists[citation needed]. The population of Hispaniola at the point of first European contact is estimated at between several hundred thousand to over a million people[citation needed], but by 1514, it had dropped to a mere 35,000.[6] By 1509, the Spanish had successfully conquered Puerto Rico and subjugated the approximately 30,000 Taíno inhabitants. By 1530 there were 1148 Taíno left alive in Puerto Rico.[9]

Taíno influence has survived even until today, though, as can be seen in the religions, languages, and music of Caribbean cultures.[10] The Lokono and other South American groups resisted colonization for a longer period, and the Spanish remained unable to subdue them throughout the 16th century. In the early 17th century, they allied with the Spanish against the neighboring Kalina (Caribs), who allied with the English and Dutch.[11] The Lokono benefited from trade with European powers into the early 19th century, but suffered thereafter from economic and social changes in their region, including the end of the plantation economy. Their population declined until the 20th century, when it began to increase again.[12]

Most of the Arawak of the Antilles died out or intermarried after the Spanish conquest. In South America, Arawakan-speaking groups are widespread, from southwest Brazil to the Guianas in the north, representing a wide range of cultures. They are found mostly in the tropical forest areas north of the Amazon. As with all Amazonian native peoples, contact with white settlement has led to culture change and depopulation among these groups.[13]

Modern population and descendants

Arawak people gathered for an audience with the Dutch Governor in Paramaribo, Suriname, 1880

The Spaniards who arrived in the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in 1492, and later in Puerto Rico, did not bring women on their first expeditions. Many of the explorers and early colonists took Taíno women as sexual partners or concubines, whether consensually or not, and those women bore mestizo or mixed-race children. Through the generations, numerous mixed-race descendants still identify as Taino or Lokono.

In the 21st century, these descendants, about 10,000 Lokono, live primarily in the coastal areas of Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, with additional Lokono living throughout the larger region. Unlike many indigenous groups in South America, the Lokono population is growing.[14]

Notable Arawak

John P. Bennett (Lokono), first Amerindian ordained as an Anglican priest in Guyana, linguist and author of An Arawak-English Dictionary (1989).

George Simon (Lokono), artist and archaeologist from Guyana.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arawak. |

- Arawakan languages

- Cariban languages

- Garifuna language

- Jean La Rose

- List of indigenous names of Eastern Caribbean islands

- Maipurean languages

Adaheli, the Sun in the mythology of the Orinoco region

Aiomun-Kondi, Arawak deity, created the world in Arawak mythology- Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

References

^ ab Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

^ Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 29. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

^ Tennesen, M. "Uncovering the Arawacks". JSTOR 41780608.

^ Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. pp. 30–48. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

^ ab "Hispaniola | Genocide Studies Program". gsp.yale.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

^ Keegan, William F. (1992). Destruction of the Taino. pp. 51–56.

^ Whitehead, Neil L. (20 March 1984). "Carib cannibalism. The historical evidence". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 70 (1): 69–87. doi:10.3406/jsa.1984.2239.

^ "Puerto Rico | Genocide Studies Program". gsp.yale.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

^ "Exploring the Early Americas".

^ Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. pp. 39–42. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

^ Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. pp. 30, 211. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

^ Lagasse, P. "Arawak".

^ Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethno-historical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 211. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

Bibliography

- Jesse, C., (2000). The Amerindians in St. Lucia (Iouanalao). St. Lucia: Archaeological and Historical Society.

- Haviser, J. B.,Wilson, S. M. (ed.), (1997). Settlement Strategies in the Early Ceramic Age. In The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, Gainesville, Florida: University Press.

- Hofman, C. L., (1993). The Native Population of Pre-columbian Saba. Part One. Pottery Styles and their Interpretations. [Ph.D. dissertation], Leiden: University of Leiden (Faculty of Archaeology).

- Haviser, J. B., (1987). Amerindian cultural Geography on Curaçao. [Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation], Leiden: Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University.

Handler, Jerome S. (Jan 1977). "Amerindians and Their Contributions to Barbadian Life in the Seventeenth Century". The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. no.3. Barbados: Museum and Historical Society. 33: 189–210.

- Joseph, P. Musée, C. Celma (ed.), (1968). "LГhomme Amérindien dans son environnement (quelques enseignements généraux)", In Les Civilisations Amérindiennes des Petites Antilles, Fort-de-France: Départemental d’Archéologie Précolombienne et de Préhistoire.

- Bullen, Ripley P., (1966). "Barbados and the Archeology of the Caribbean", The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, 32.

- Haag, William G., (1964). A Comparison of Arawak Sites in the Lesser Antilles. Fort-de-France: Proceedings of the First International Congress on Pre-Columbian Cultures of the Lesser Antilles, pp. 111–136

- Deutsche, Presse-Agentur. "Archeologist studies signs of ancient civilization in Amazon basin", Science and Nature, M&C, 08/02/2010. Web. 29 May 2011.

Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2014.