P. T. Barnum

| P. T. Barnum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut | |

In office 1875–1876 | |

| Member of the Connecticut House of Representatives from the Fairfield, Connecticut district | |

In office 1866–1869 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-07-05)July 5, 1810 Bethel, Connecticut, United States |

| Died | April 7, 1891(1891-04-07) (aged 80) Bridgeport, Connecticut, United States |

| Resting place | Mountain Grove Cemetery, Bridgeport |

| Political party | Democratic (1824–1854) Republican (1854–1891) |

| Spouse(s) | Charity Hallett (m. 1829; died 1873) Nancy Fish (m. 1874; died 1891) |

| Occupation | Businessman (entertainment) |

| Known for | Founding the Barnum & Bailey Circus legislative sponsor of 1879 Connecticut anti-contraception law |

| Signature | |

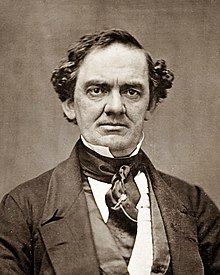

Phineas Taylor Barnum (/ˈbɑːrnəm/; July 5, 1810 – April 7, 1891) was an American showman, politician, and businessman remembered for promoting celebrated hoaxes and for founding the Barnum & Bailey Circus (1871–2017).[1] He was also an author, publisher, and philanthropist, though he said of himself: "I am a showman by profession… and all the gilding shall make nothing else of me".[2] According to his critics, his personal aim was "to put money in his own coffers."[2] He is widely credited with coining the adage "There's a sucker born every minute",[3] although no evidence can be found of him saying this.

Barnum became a small-business owner in his early twenties and founded a weekly newspaper before moving to New York City in 1834. He embarked on an entertainment career, first with a variety troupe called "Barnum's Grand Scientific and Musical Theater", and soon after by purchasing Scudder's American Museum which he renamed after himself. He used the museum as a platform to promote hoaxes and human curiosities such as the Fiji mermaid and General Tom Thumb.[4] In 1850, he promoted the American tour of singer Jenny Lind, paying her an unprecedented $1,000 a night for 150 nights. He suffered economic reversals in the 1850s due to bad investments, as well as years of litigation and public humiliation, but he used a lecture tour as a temperance speaker to emerge from debt. His museum added America's first aquarium and expanded the wax-figure department.

Barnum served two terms in the Connecticut legislature in 1865 as a Republican for Fairfield, Connecticut. He spoke before the legislature concerning the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude: "A human soul, 'that God has created and Christ died for,' is not to be trifled with. It may tenant the body of a Chinaman, a Turk, an Arab, or a Hottentot—it is still an immortal spirit".[5] He was elected in 1875 as Mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he worked to improve the water supply, bring gas lighting to streets, and enforce liquor and prostitution laws. He was also instrumental in starting Bridgeport Hospital, founded in 1878, and was its first president.[6] Nevertheless, the circus business was the source of much of his enduring fame. He established "P. T. Barnum's Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome", a traveling circus, menagerie, and museum of "freaks" which adopted many names over the years.

Barnum died of a stroke at his home residence in 1891 and was buried in Mountain Grove Cemetery, Bridgeport, which he designed himself.[7]

Contents

1 Early life

2 The Greatest Showman

2.1 Fiji mermaid and Tom Thumb

2.2 Jenny Lind

2.3 Diversified leisure-time activities

3 Circus king

4 Author and debunker

5 Role in politics and minstrel shows

6 Profitable philanthropy

7 Personal life and death

8 Legacy

8.1 The Greatest Showman

9 In popular culture

10 Publications

11 See also

12 References

13 Further reading

14 External links

Early life

Barnum was born in Bethel, Connecticut, the son of innkeeper, tailor, and store-keeper Philo Barnum (1778–1826) and his second wife Irene Taylor. His maternal grandfather Phineas Taylor was a Whig, legislator, landowner, justice of the peace, and lottery schemer who had a great influence on him.

Barnum had several businesses over the years, including a general store, a book auctioning trade, real estate speculation, and a statewide lottery network. He started a weekly newspaper in 1829 called The Herald of Freedom in Danbury, Connecticut. His editorials against the elders of local churches led to libel suits and a prosecution which resulted in imprisonment for two months, but he became a champion of the liberal movement upon his release.[citation needed] He sold his store in 1834 and moved to New York City because lotteries were banned in Connecticut, cutting off his main income.[citation needed]

He began his career as a showman in 1835 when he was 25 with the purchase and exhibition of a blind and almost completely paralyzed slave woman named Joice Heth, whom an acquaintance was trumpeting around Philadelphia as George Washington's former nurse and 161 years old. Slavery was already outlawed in New York, but he exploited a loophole which allowed him to lease her for a year for $1,000, borrowing $500 to complete the sale. Heth died in February 1836, at no more than 80 years old. Barnum had worked her for 10 to 12 hours a day, and he hosted a live autopsy of her body in a New York Saloon where spectators paid 50 cents to see the dead woman cut up, as he revealed that she was likely half her purported age.[8][9]

The Greatest Showman

Barnum had a year of mixed success with his first variety troupe called "Barnum's Grand Scientific and Musical Theater", followed by the Panic of 1837 and three years of difficult circumstances. He purchased Scudder's American Museum in 1841, located at Broadway and Ann Street, New York City. He improved the attraction, upgrading the building and adding exhibits, then renamed it "Barnum's American Museum"; it became a popular showplace. He added a lighthouse lamp which attracted attention up and down Broadway and flags along the roof's edge that attracted attention in daytime, while giant paintings of animals between the upper windows drew attention from pedestrians. The roof was transformed to a strolling garden with a view of the city, where he launched hot-air balloon rides daily. A changing series of live acts and curiosities were added to the exhibits of stuffed animals, including albinos, giants, little people, jugglers, magicians, exotic women, detailed models of cities and famous battles, and a menagerie of animals.

Fiji mermaid and Tom Thumb

1866 newspaper advertisement for Barnum's American Museum located on Ann Street in Manhattan

In 1842, Barnum introduced his first major hoax: a creature with the head of a monkey and the tail of a fish known as the "Feejee" mermaid. He leased the "mermaid" from fellow museum owner Moses Kimball of Boston, who became his friend, confidant, and collaborator.[10][11] Barnum described his hoaxes and justified perpetrating them by saying that they were advertisements to draw attention to the museum. "I don't believe in duping the public," he claimed, "but I believe in first attracting and then pleasing them."[12]

He followed that with the exhibition of Charles Stratton, the dwarf called "General Tom Thumb" ("the Smallest Person that ever Walked Alone") who was then four years old but was stated to be 11. With heavy coaching and natural talent, the boy was taught to imitate people from Hercules to Napoleon. By five, he was drinking wine and by seven smoking cigars for the public's amusement.

In 1843, Barnum hired traditional Native American dancer fu-Hum-Me, the first of many Native Americans whom he presented. During 1844–45, he toured with General Tom Thumb in Europe and met Queen Victoria, who was amused[13] but saddened by the little man, and the event was a publicity coup. It opened the door to visits from royalty throughout Europe, including the Tzar of Russia, and enabled Barnum to acquire dozens of new attractions, including automatons and other mechanical marvels; he was almost able to buy the birth home of William Shakespeare. During this time, he went on a spending spree and bought other museums, including the artist Rembrandt Peale's Peale's Museum in Philadelphia,[14] the nation's first major museum. By late 1846, Barnum's Museum was drawing 400,000 visitors a year.[4]

Jenny Lind

Castle Garden, New York, venue of Lind's first American concerts

During his Tom Thumb tour of England, Barnum had become aware of the popularity of Jenny Lind, the "Swedish Nightingale". Her career was at its height in Europe; she was unpretentious, shy, and devout, and possessed a crystal-clear soprano voice projected with a wistful quality and earnestness that audiences found touching. Barnum had never heard her and conceded to being unmusical himself.[15] He approached her to sing in America at $1,000 a night for 150 nights, all expenses paid by him. He knew that his risk was great: "'The public' is a very strange animal, and although a good knowledge of human nature will generally lead a caterer of amusement to hit the people right, they are fickle and ofttimes perverse."[16] But he was confident that Lind's reputation for morality and philanthropy could be turned to good use in his publicity.[15]

Lind demanded the fee in advance. Barnum agreed, and she accepted the offer, which would permit her to raise a huge fund for charities, principally endowing schools for poor children in Sweden.[17] Barnum borrowed heavily on his mansion and his museum to raise the money to pay Lind,[16] but he was still short of funds; so he persuaded a Philadelphia minister that Lind would be a good influence on American morals, and the minister lent him the final $5,000. The contract also gave Lind the option of withdrawing from the tour after 60 or 100 performances, paying Barnum $25,000 if she did so.[17] Lind and her small company sailed to America in September 1850, but she was a celebrity even before she arrived because of Barnum's months of preparations; close to 40,000 people greeted her at the docks and another 20,000 at her hotel. The press was also in attendance, and "Jenny Lind items" were available to buy.[18] When she realized how much money Barnum stood to make from the tour, Lind insisted on a new agreement which he signed on September 3, 1850. This gave her the original fee plus the remainder of each concert's profits after Barnum's $5,500 management fee was paid. She was determined to accumulate as much money as possible for her charities.[15]

The tour began with a concert at Castle Garden on September 11, 1850, and it was a major success, recouping Barnum four times his investment. Washington Irving proclaimed, "She is enough to counterbalance, of herself, all the evil that the world is threatened with by the great convention of women. So God save Jenny Lind!"[18] Tickets for some of her concerts were in such demand that Barnum sold them by auction. The enthusiasm of the public was so strong that the American press coined the term "Lind mania".[19] The blatant commercialism of Barnum's ticket auctions distressed Lind,[19] and she persuaded him to make a substantial number of tickets available at reduced prices.[20]

On the tour, Barnum's publicity always preceded Lind's arrival and whipped up enthusiasm; he had up to 26 journalists on his payroll.[21] After New York, the company toured the east coast with continued success, and later took in Cuba and the southern states of the U.S. By early 1851, Lind had become uncomfortable with Barnum's relentless marketing of the tour, and she invoked a contractual right to sever her ties with him. They parted amicably, and she continued the tour for nearly a year under her own management.[15] Lind gave 93 concerts in America for Barnum, earning her about $350,000, while Barnum netted at least $500,000 (equivalent to $14,708,000 in 2017).[22]

Diversified leisure-time activities

Using profits from the Lind tour, Barnum's next challenge was to change public attitudes about the theater. Widely seen as "dens of evil", Barnum wanted to position them as palaces of edification and delight, and as respectable middle-class entertainment. He built New York City's largest and most modern theater, naming it the "Moral Lecture Room." He hoped this would avoid seedy connotations and attract a family crowd and win the approval of the moral crusaders of New York City. He started the nation's first theatrical matinées, to encourage families and to lessen the fear of crime. He opened with The Drunkard, a thinly disguised temperance lecture (he had become a teetotaler after returning from Europe). He followed that with melodramas, farces, and historical plays, put on by highly regarded actors. He watered down Shakespearean plays and others such as Uncle Tom's Cabin to make them family entertainment.[citation needed]

He organized flower shows, beauty contests, dog shows, poultry contests, but the most popular were baby contests (fattest baby, handsomest twins, etc.). In 1853, he started a pictorial weekly newspaper Illustrated News and a year later completed his autobiography, which through many revisions, sold more than one million copies. Mark Twain loved the book but the British Examiner thought it "trashy" and "offensive" and "inspired...nothing but sensations of disgust...and sincere pity for the wretched man who compiled it."[23]

In the early 1850s, Barnum began investing to develop East Bridgeport, Connecticut. He made substantial loans to the Jerome Clock Company, to get it to move to his new industrial area. But by 1856, the company went bankrupt, taking Barnum's wealth with it. This started four years of litigation and public humiliation. Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed that Barnum's downfall showed "the gods visible again" and other critics celebrated Barnum's moral comeuppance. But his friends supported him, and Tom Thumb, now touring on his own, offered his services and they undertook another European tour. Barnum also started a lecture tour, mostly as a temperance speaker. By 1860, he emerged from debt and built a mansion "Lindencroft" (his palace "Iranistan" had burnt down in 1857) and he resumed ownership of his museum.

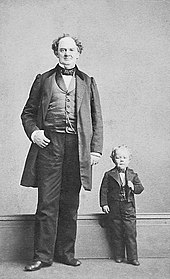

Barnum with Commodore Nutt, photograph by Charles DeForest Fredricks

Despite critics who predicted he could not revive the magic, Barnum went on to greater success. He created America's first aquarium and expanded the wax figure department of the museum. His "Seven Grand Salons" demonstrated the Seven Wonders of the World. He created a rogues gallery. The collections expanded to four buildings and he published a "Guide Book to the Museum" which claimed 850,000 'curiosities.'[24]

Late in 1860, the Siamese Twins, Chang and Eng, came out of retirement (they needed more money to send their numerous children to college). The Twins had had a touring career on their own and went to live on a North Carolina plantation with their families and slaves, under the name of "Bunker." They appeared at Barnum's Museum for six weeks. Also in 1860, Barnum introduced the "man-monkey" William Henry Johnson, a microcephalic black dwarf who spoke a mysterious language created by Barnum. In 1862, he discovered the giantess Anna Swan and Commodore Nutt, a new Tom Thumb, with whom Barnum visited President Abraham Lincoln at the White House. During the Civil War, Barnum's museum drew large audiences seeking diversion from the conflict. He added pro-Unionist exhibits, lectures, and dramas, and he demonstrated commitment to the cause. For example, in 1864 Barnum hired Pauline Cushman, an actress who had served as a spy for the Union, to lecture about her "thrilling adventures" behind Confederate lines. Barnum's Unionist sympathies incited a Confederate arsonist to start a fire in 1864. On July 13, 1865, Barnum's American Museum burned to the ground from a fire of unknown origin. Barnum re-established the Museum at another location in New York City, but this too was destroyed by fire in March 1868. This time the loss was too great, and Barnum retired from the museum business.

Circus king

Winter Quarters of the Great Barnum-London Show before 1886

Share of the Barnum and Bailey Ltd, issued 24. January 1902

Barnum did not enter the circus business until he was 60 years old. In Delavan, Wisconsin in 1870 with William Cameron Coup, he established "P. T. Barnum's Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome", a traveling circus, menagerie, and museum of "freaks". It went through various names: "P.T. Barnum's Travelling World's Fair, Great Roman Hippodrome and Greatest Show On Earth", and after an 1881 merger with James Bailey and James L. Hutchinson, "P.T. Barnum's Greatest Show On Earth, And The Great London Circus, Sanger's Royal British Menagerie and The Grand International Allied Shows United", soon shortened to "Barnum & Bailey's". This entertainment phenomenon was the first circus to display three rings,[25] which made it the largest circus the world had ever seen.[citation needed] The show's first primary attraction was Jumbo, an African elephant he purchased in 1882 from the London Zoo. The Barnum and Bailey Circus still contained acts similar to his Traveling Menagerie: acrobats, freak shows, and the world-famous General Tom Thumb. Despite more fires, train disasters, and other setbacks, Barnum plowed ahead, aided by circus professionals who ran the daily operations. He and Bailey split up again in 1885, but came back together in 1888 with the "Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show On Earth", later "Barnum & Bailey Circus", which toured the world.

Barnum became known as the Shakespeare of Advertising, due to his innovative and impressive ideas.[26] He knew how to draw patrons in, by giving them a glimpse of something that had never been seen before. He was, at times, accused of being deceptive and promoting false advertising.[citation needed]

Barnum was one of the very first circus owners to move his circus by train (and probably the very first to buy his own train). His friend, William C. Coup, helped him get railroad cars to make tour traveling easier. Given the lack of paved highways in America, this turned out to be a shrewd business move that vastly extended Barnum's geographical reach. In this new field, Barnum leaned more on the advice of Coup, Bailey, and other business partners, most of whom were young enough to be his sons.

Author and debunker

Parody of Jenny Lind's first American tour for P.T. Barnum, New York City, October 1850

Barnum wrote several books, including Life of P.T. Barnum (1854), The Humbugs of the World (1865), Struggles and Triumphs (1869), and The Art of Money-Getting (1880).[27]

One of Barnum's more successful methods of self-promotion was mass publication of his autobiography. Barnum eventually gave up his copyright to allow other printers to sell inexpensive editions. At the end of the 19th century the number of copies printed was second only to the New Testament in North America.[citation needed]

"Hum-Bug": a cartoon by H. L. Stephens (1851)

Often referred to as the "Prince of Humbugs", Barnum saw nothing wrong in entertainers or vendors using hoaxes (or "humbug", as he termed it) in promotional material, as long as the public was getting value for money. However, he was contemptuous of those who made money through fraudulent deceptions, especially the spiritualist mediums popular in his day, testifying against noted spirit photographer William H. Mumler in his trial for fraud. Prefiguring illusionists like Harry Houdini, Barnum exposed "the tricks of the trade" used by mediums to cheat the bereaved. In The Humbugs of the World, he offered $500 to any medium who could prove power to communicate with the dead.

Role in politics and minstrel shows

Barnum was significantly involved in politics, focusing on race, slavery, and sectionalism in the period leading up to the American Civil War. He had some of his first success as an impresario through Joice Heth, a slave he hired. Around 1850, he was involved in a hoax about a weed that would turn black people white.[citation needed]

Barnum was a producer and promoter of blackface minstrelsy. Barnum's minstrel shows often used double-edged humor. While replete with black stereotypes, Barnum's shows satirized as in a stump speech in which a black phrenologist (like all minstrel performers, a white man in blackface) made a dialect speech parodying lectures given at the time to "prove" the superiority of the white race: "You see den, dat clebber man and dam rascal means de same in Dutch, when dey boph white; but when one white and de udder's black, dat's a grey hoss ob anoder color."[28]

Promotion of minstrel shows led to his sponsorship in 1853 of H.J. Conway's politically watered-down stage version of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin; the play, at Barnum's American Museum, gave the story a happy ending, with Tom and other slaves freed. The success led to a play based on Stowe's Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. His opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which supported slavery, led him to leave the Democratic Party to become a member of the new anti-slavery Republican Party. He had evolved from a man of common stereotypes of the 1840s to a leader for emancipation by the Civil War.[citation needed]

While he claimed "politics were always distasteful to me", Barnum was elected to the Connecticut legislature in 1865 as Republican representative for Fairfield and served four terms.[5][29] In the debate over slavery and African-American suffrage with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Barnum spoke before the legislature and said, "A human soul, 'that God has created and Christ died for,' is not to be trifled with. It may tenant the body of a Chinaman, a Turk, an Arab or a Hottentot – it is still an immortal spirit."[5]

Barnum was notably, as a Connecticut state senator, the legislative sponsor of a law enacted by the Connecticut General Assembly in 1879 that prohibited the use of "any drug, medicinal article or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception", and also made it a crime to act as an "accessory" to the use of contraception, which remained in effect in Connecticut until being overturned in 1965 by the U.S. Supreme Court Griswold v. Connecticut decision.[30][31][32][33]

Barnum ran for the United States Congress in 1867 and lost to his third cousin William Henry Barnum. In 1875, Barnum as mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut, worked to improve the water supply, bring gas lighting to streets, and enforce liquor and prostitution laws. Barnum was instrumental in starting Bridgeport Hospital, founded in 1878, and was its first president.[6]

Profitable philanthropy

Barnum enjoyed what he publicly dubbed "profitable philanthropy". In Barnum's own words: "I have no desire to be considered much of a philanthropist...if by improving and beautifying our city Bridgeport, Connecticut, and adding to the pleasure and prosperity of my neighbors, I can do so at a profit, the incentive to 'good works' will be twice as strong as if it were otherwise."[34] In line with this philosophy was Barnum's pursuit of major American museums and spectacles. Less known are Barnum's significant contributions to Tufts University. Barnum was appointed to the Board of Trustees prior to the University's founding and made several significant contributions to the fledgling institution. The most noteworthy example of this was his gift in 1883 of $50,000 (equivalent to $1,313,214 in 2017), to establish a museum and hall for the Department of Natural History, which later housed the department of biology.[35] Because of the relationship between Barnum and Tufts, Jumbo the elephant became the school's mascot, and Tufts students are known as "Jumbos".[36]

Personal life and death

On November 8, 1829, Barnum married Charity Hallett.[37] The couple had four children: Caroline Cornelia (1833–1911), Helen Maria (1840–1920), Frances Irena (1842–1844), and Pauline Taylor (1846–1917).[38]

His wife died on November 19, 1873.[38] Barnum married Nancy Fish the following year, 1874.[39]

Barnum died from a stroke at home in 1891.[29] He was buried in Mountain Grove Cemetery, Bridgeport, Connecticut, a cemetery he designed.[7]

Legacy

Obverse of the Bridgeport Half Dollar

Barnum built four mansions in Bridgeport, Connecticut: Iranistan, Lindencroft, Waldemere, and Marina. Iranistan was the most notable: a fanciful and opulent Moorish Revival splendor designed by Leopold Eidlitz with domes, spires and lacy fretwork, inspired by the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, England. This mansion was built 1848 but burned down in 1857.[40] The Marina Mansion was demolished by the University of Bridgeport in 1964 in order to build their cafeteria.[41]

At his death, most critics had forgiven Barnum and he was praised for good works, hailed as an icon of American spirit and ingenuity, and was perhaps the most famous American in the world. Just before his death, he gave permission to the Evening Sun to print his obituary, so that he might read it. On April 7, 1891, Barnum asked about the box office receipts for the day; a few hours later, he was dead.[29]

P. T. Barnum, sculpted by Thomas Ball (1887), Seaside Park, Bridgeport, Connecticut

In 1893, a statue in his honor was placed at Seaside Park, by the water in Bridgeport.[42] Barnum had donated the land for this park in 1865.

His circus was sold to Ringling Brothers on July 8, 1907 for $400,000 (about $10.45 million in 2017 dollars).[6] The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey circuses ran separately until they merged in 1919 forming the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

The Tufts University Biology Building is named in honor of Barnum. Jumbo eventually became the mascot of Tufts University, in honor of Barnum's 1889 donation of the elephant's stuffed hide.

In 1936, for the centennial of the city of Bridgeport, Connecticut, his portrait was used for the obverse of the commemorative Bridgeport Half Dollar.[43]

Walt Kelly, who grew up in Bridgeport, named the Pogo character P.T. Bridgeport after Barnum, and endowed the circus operator bear with a Barnum-like outsized personality and word balloons with lettering that resembled 19th century circus posters giving graphic depiction of the sort of colorful language Barnum was prone to use.

An annual six-week Barnum Festival was held for many years in Bridgeport, Connecticut, as a tribute to Barnum.[44]

To honor the 200th anniversary of Barnum's birth, the Bethel Historical Society commissioned a life-size sculpture, created by local resident David Gesualdi, that stands outside the public library.[45] The statue was dedicated on September 26, 2010.[46]

The Bridgeport & Port Jefferson Steamboat Company, which Barnum co-founded in 1883 with Charles E. Tooker, continues to operate across the Long Island Sound between Port Jefferson, New York, and Bridgeport, as of at least 2017. The company owns and operates three vessels, one of which is named the (M.V.) PT Barnum.

The Barnum Museum, located in Bridgeport, Connecticut, is home to many of Barnum's various oddities and curiosities.

The Greatest Showman

In December 2017, an American film titled, "The Greatest Showman" was released. This musical was based loosely on the life of Barnum (portrayed by Hugh Jackman). Directed by Michael Gracey, "The Greatest Showman" shows PT Barnum as a young boy with a flair for entertainment. The young Barnum then grows up, marries his childhood love (Charity Hallet),[47] starts the circus, and tours with Jenny Lind.[48] The film was released seven months after the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus permanently dissolved.

In popular culture

Films and television:

A Lady's Morals (1930) – played by Wallace Beery

Jenny Lind (1932) – played by André Berley

The Mighty Barnum (1934) – played by Wallace Beery

The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) – played by a cast which included many from the Ringling Bros/Barnum & Bailey Circus

Jules Verne's Rocket to the Moon (1967) – played by Burl Ives

Barnum (1986) – played by Burt Lancaster; made-for-TV movie

A Bug's Life (1998) - P.T. Flea, a circus ringmaster, whose name is similar to P.T Barnum

P. T. Barnum (1999) – played by Beau Bridges; made-for-TV movie

Gangs of New York (2002) – played by Roger Ashton-Griffiths. Barnum's American Museum is mentioned and its destruction (accurate in method but inaccurate in chronology and circumstance) is briefly shown.

DC's Legends of Tomorrow (2017) – played by Billy Zane[49]

The Greatest Showman (2017) – a musical, loosely based around the origins of P.T. Barnum and his circus. Hugh Jackman plays Barnum and co-produced the film.[50][51]

Theatre:

Barnum (1980) – Broadway musical based on Barnum's life

It's Bad for Ya – by George Carlin, who references Barnum on the "All Children Are Special" piece

El Gran Showman: Puesta en escena (2018), Latin American version of the musical based on the film by the same name, The Greatest Showman, by Proscenia Studio, Tabasco, México

Books:

The Thunder of Giants[52] by Joel Fishbane. St. Martin's Press, New York. (2015). Historical fiction concerning Anna Swan, the Nova Scotia giantess who Barnum brought to New York in 1862. The book touches on Barnum's politics and the lives of other exhibits in the American Museum.

Music:

Elvis Costello's "Red Cotton", from his 2009 album Secret, Profane & Sugarcane, is widely understood to be about Barnum and his opposition to the slave trade.- P.T. Barnum is mentioned in the Grateful Dead song "U.S. Blues".

- Barnum & Bailey is mentioned in the jazz standard "It's Only a Paper Moon". The lyrics "It's a Barnum and Bailey world. Just as phony as it can be. But it wouldn't be make-believe if you believed in me" are sung by Blanche DuBois in Scene 7 of "A Streetcar Named Desire" by Tennessee Williams.[53]

XTC references 'Mrs. Barnum' in their song "Dear Madame Barnum".

Karl King, who played in Barnum’s circus band[citation needed], composed Barnum and Bailey's Favorite.

Publications

The Life of P.T. Barnum: Written By Himself. Originally published New York: Redfield, 1855. Reprinted., Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2000. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-252-06902-1.

Struggles and Triumphs, or Forty Years' Recollections of P.T. Barnum. Originally published 1869. Reprinted., Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2003.

ISBN 0-7661-5556-0 (Part 1) and

ISBN 0-7661-5557-9 (Part 2). 1882 edition on the Internet Archive

Art of Money Getting, or, Golden Rules for Making Money]. Originally published 1880. Reprinted., Bedford, MA: Applewood, 1999.

ISBN 1-55709-494-2.

The Wild Beasts, Birds, and Reptiles of the World: The Story of their Capture. Pub. 1888, R. S. Peale & Company, Chicago.

Why I Am A Universalist. Originally published 1890 Reprint Kessinger Pub Co.

ISBN 1-4286-2657-3

See also

- Barnum effect

- Barnum's American Museum

Barnum's Aquarial Gardens, Boston, Massachusetts (1862–1863)- Bridgeport & Port Jefferson Ferry

- Cardiff Giant

- Carl Hagenbeck

- Colonel Routh Goshen

- Fedor Jeftichew

- Fiji Mermaid

- General Tom Thumb

- Human zoo

- Isaac W. Sprague

- James Anthony Bailey

- Jenny Lind private railroad car

- Joice Heth

- Jumbo

- Lucia Zarate

- Moses Kimball

- Nellie Keeler

- There's a sucker born every minute

- The Greatest Show on Earth

- Tufts University

- Wild Men of Borneo

- Zip the Pinhead

References

^ North American Theatre Online: Phineas T. Barnum

^ ab Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. vi

^ Shapiro, Fred R. The Yale Book of Quotations. New Haven: Yale UP, 2006. p. 44

^ ab Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. 73

^ abc Barnum, Phineas (1888). "The life of P.T. Barnum". Ebook and Texts Archive – American Libraries. Buffalo, N.Y.: The Courier Company. p. 237.

^ abc Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995

^ ab Rogak, Lisa (2004). Stones and Bones of New England: A guide to unusual, historic, and otherwise notable cemeteries. Globe Pequat. ISBN 0-7627-3000-5.

^ Mansky, Jackie (December 22, 2017), P.T. Barnum Isn't the Hero the "Greatest Showman" Wants You To Think – His path to fame and notoriety began by exploiting an slave woman, in life and in death, as entertainment for the masses, Smithsonian

^ Freed, Robin. "Joice Heth". MA candidate, University of Virginia American Studies Department. Archived from the original on May 18, 2002. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

^ Schweitzer, Marlis. "Barnum's Last Laugh? General Tom Thumb's Wedding Cake In The Library Of Congress." Performing Arts Resources 2011; 28.: 116. Associates Programs Source Plus. Web. 8 Dec. 2012.

^ Stabile, Susan M (2010). "Still(Ed) Lives". Early American Literature. 45 (2): 371–95. doi:10.1353/eal.2010.0020.

^ Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. 47

^ Martin, Gary. "'We are not amused' - the meaning and origin of this phrase". Phrasefinder.

^ "Peale's Philadelphia Museum - Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia". philadelphiaencyclopedia.org.

^ abcd Rogers, Francis. "Jenny Lind", The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (July 1946), pp. 437–48 (subscription required)

^ ab Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. 92

^ ab Miller, Philip L. "Review: P. T. Barnum Presents Jenny Lind: The American Tour of the Swedish Nightingale", American Music, Spring 1983, pp. 78–80 (subscription required)

^ ab Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. 99

^ ab Linkon, Sherry Lee. "Reading Lind Mania: Print Culture and the Construction of Nineteenth-Century Audiences", Book History, Vol. 1 (1998), pp. 94–106 (subscription required)

^ "Jenny Lind's Progress in America", The Observer, October 6, 1850, p. 3

^ Hambrick, Keith S. "P. T. Barnum Presents Jenny Lind – The American Tour of the Swedish Nightingale", Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Spring, 1981), pp. 208–09 (subscription required)

^ "America", The Times, June 28, 1851, p. 5

^ Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. 120

^ Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt 1995, p. 138

^ Mosier, Jennifer L (1999). "The Big Attraction: The Circus Elephant And American Culture". Journal of American Culture. 22 (2): 7. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.1999.2202_7.x.

^ "The Shakespeare of Advertising's Rules for Jumbo Success", There's a Customer Born Every Minute, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 103–113, 2015-10-10, doi:10.1002/9781119201908.ch8, ISBN 9781119201908, retrieved 2018-10-03

^

The Art of Money-Getting

^ Lott 1993, p. 78

^ abc "The Great Showman Dead". The New York Times. April 8, 1891. Retrieved July 21, 2007.Bridgeport, Connecticut, April 7, 1891. At 6:22 o'clock to-night the long sickness of P.T. Barnum came to an end by his quietly passing away at Marina, his residence in this city.

^ "Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut – Today in History"

^ "P.T. Barnum, Justice Harlan, and Connecticut's Role in the Development of the Right to Privacy". Federal Bar Council Quarterly. 13 December 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

^ "Connecticut and the Comstock Law". Connecticut History. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

^ "Planned Parenthood, The Pill, and P. T. Barnum". Huffington Post. 18 September 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

^ Barnum, P.T. (1883). Struggles and Triumphs; Or, Forty Years' Recollections of P.T. Barnum. Buffalo, N.Y.: The Courier Company. p. 297.

^ Miller, Russell (July 16, 2008). "Light on the Hill, Vol. 1". The Archives at Tufts University. Tufts University.

^ "Get to Know Tufts". April 22, 2010.

^ Barnum, Patrick W. "A One-Name Study for the Barnum/Barnham Surname: Notes for Phineas Taylor Barnum / Charity Hallett". Barnum Family Genealogy (official website). Retrieved December 10, 2017.

^ ab "Charity Hallett (1814–1873)". Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Additional archive on December 10, 2017.

^ Barnum, Patrick W. "A One-Name Study for the Barnum/Barnham Surname: Notes for Nancy Fish". Barnum Family Genealogy (official website). Retrieved December 10, 2017.

^

Barnum Museum Core Exhibits Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Marina Park Historic District, Bridgeport City, Fairfield County, Bridgeport CT, 06604". www.livingplaces.com.

^ "Barnum Statue Unveiled". The New York Times. July 4, 1893.

^ Chuck Slater (November 18, 2001). "A Coin True to Barnum, Controversy and All". The New York Times.

^ Michael Knight, "Barnum Festival Revels in Hoopla and Humbug", The New York Times, June 20, 1975, p. 35.

^ Marietta Homayon (July 8, 2004). "Town gets grant to promote Barnum". The Dansbury News-Times.

^ FitzGerald, Eileen (July 15, 2010). "Barnum's Ivy Island to be showcased at celebration". Danbury News Times.

^ "Charity (Hallett) Barnum (1808-1873) | WikiTree FREE Family Tree". www.wikitree.com. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

^ Mansky, Jackie (December 22, 2017). "P.T. Barnum Isn't the Hero the "Greatest Showman" Wants You to Think". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

^ Abrams, Natalie (June 14, 2017). "Legends of Tomorrow casts Billy Zane as P.T. Barnum". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

^ Cachero, Paulina (20 December 2017). "'The Greatest Showman': 8 of the Film's Stars and Their Real-Life Inspirations". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

^ Kellem, Betsy Golden (22 December 2017). "The Greatest Showman: The True Story of P.T. Barnum and Jenny Lind". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

^ The Thunder of Giants

^ Williams, T. (2000). A streetcar named desire and other plays. London: Penguin.

Further reading

- Adams, Bluford. E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

ISBN 0-8166-2631-6. - Alderson, William T., ed. Mermaids, Mummies, and Mastodons: The Emergence of the American Museum. Washington, DC: American Association of Museums for the Baltimore City Life Museums, 1992.

- Barnum, Patrick Warren. Barnum Genealogy: 650 Years of Family History. Boston: Higginson Book Co., 2006.

ISBN 0-7404-5551-6 (hardcover),

ISBN 0-7404-5552-4 (softcover), LCCN 2005903696. - Benton, Joel. The Life of Phineas T. Barnum, [1].

- Betts, John Rickards. "P.T. Barnum and the Popularization of Natural History." Journal of the History of Ideas 20, no. 3 (1959): 353-368.

- Cook, James W. The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

ISBN 0-674-00591-0. Relates Barnum's Fiji Mermaid and What Is It? exhibits to other popular arts of the nineteenth century, including magic shows and trompe l'oeil paintings. - Harding, Les. Elephant Story: Jumbo and P. T. Barnum Under the Big Top. Jefferson, NC.: McFarland & Co., 2000.

ISBN 0-7864-0632-1. (129 p.) - Harris, Neil. Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

ISBN 0-226-31752-8.

Kunhardt, Philip B., Jr.; Kunhardt, Philip B., III; Kunhardt, Peter W. (1995). P.T. Barnum: America's Greatest Showman. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-43574-3.

Lott, Eric (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 76–78. ISBN 0-19-507832-2.

- Reiss, Benjamin. The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death, and Memory in Barnum's America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

ISBN 0-674-00636-4. Focuses on Barnum's exhibition of Joice Heth. - Saxon, Arthur H. P.T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

ISBN 0-231-05687-7. - Uchill, Ida Libert. Howdy, Sucker! What P.T. Barnum Did in Colorado. Denver: Pioneer Peddler Press, 2001.

OCLC 47773817

- Jefferson, Margo. On Michael Jackson. New York, NY: Pantheon, 2006.

ISBN 978-0-307-27765-7. Critique of Michael Jackson, including his obsession with P.T. Barnum and "Freaks."

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barnum, Phineas Taylor (1810-1891)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barnum, Phineas Taylor (1810-1891)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

The Colossal P.T. Barnum Reader: Nothing Else Like It in the Universe. Ed. by James W. Cook. Champaign, University of Illinois Press, 2005.

ISBN 0-252-07295-2.

External links

[spam link?]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phineas Taylor Barnum. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: P. T. Barnum |

Wikisource has original works written by or about: P. T. Barnum |

- Phineas Taylor Barnum papers, 1818-1993

P.T. Barnum's genealogy at the Barnum Family Genealogy website

P. T. Barnum at Find a Grave

- The Barnum Museum

- Barnum's circus affiliation

- P.T. Barnum at Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus

- Barnum's American Museum

House of Deception – An article about Barnum's handwriting & signature

The Lost Museum – A virtual reproduction of Barnum's American Museum; includes a collection of primary source materials- Entry on P.T. Barnum in the Concise Encyclopedia of Tufts History

Art of Money Getting by P.T. Barnum

Works by P. T. Barnum at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about P. T. Barnum at Internet Archive

Works by P. T. Barnum at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Full text of The Life of Phineas T. Barnum by Joel Benton, from Project Gutenberg

- P.T. Barnum did not say "There's a sucker born every minute"

- P.T. Barnum, the Shakespeare of Advertising

P.T. Barnum and Henry Bergh Bergh was founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA).

Facebook Page Bethel Historical Society, P.T. Barnum Monument, "P.T. Barnum – The Lost Legend" Documentary.- An 1890 recording of Barnum's voice

- Marina Mansion

P. T. Barnum at the Internet Broadway Database