Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne

| 1937 Paris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Second category General Exposition |

| Name | Exposition Internationale des Arts et des Techniques appliqués à la vie moderne |

| Building | Palais de Chaillot |

| Area | 101 hectares (250 acres) |

| Visitors | 31,040,955 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 45 |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| City | Paris |

| Venue | Trocadéro, Champ-de-Mars, Embankment of the Seine |

| Coordinates | 48°51′44″N 02°17′17.7″E / 48.86222°N 2.288250°E / 48.86222; 2.288250 |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | 25 May 1937 (1937-05-25) |

| Closure | 25 November 1937 (1937-11-25) |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Brussels International Exposition (1935) in Brussels |

| Next | 1939 New York World's Fair in New York City |

| Specialized Expositions | |

| Previous | ILIS 1936 in Stockholm |

| Next | Second International Aeronautic Exhibition in Helsinki |

The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life) was held from 25 May to 25 November 1937 in Paris, France. Both the Musée de l'Homme and the Palais de Tokyo, which houses the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, were created for this exhibition that was officially sanctioned by the Bureau International des Expositions.

Contents

1 Exhibitions

2 Pavilions

2.1 Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux

2.2 Canadian Pavilion

2.3 Spanish Pavilion

2.4 German Pavilion

2.5 Soviet Pavilion

2.6 Italian Pavilion

2.7 British Pavilion

3 Awards

4 Festivals of the Exposition

5 Reproduction of the Soviet pavilion

6 Gallery

7 See also

8 Further reading

9 References

10 External links

Exhibitions

the Soviet pavilion and the German pavilion near the Eiffel Tower

At first the centerpiece of the exposition was to be a 2,300-foot (700 m) tower ("Phare du Monde") which was to have a spiraling road to a parking garage located at the top and a hotel and restaurant located above that. The idea was abandoned as far too expensive.[1]

Pavilions

Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux

The Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux (Pavilion of New Times) was a tent pavilion designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.[2]

Canadian Pavilion

Fitting in the architectural master-plan of the master architect Jacques Gréber at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, and inspired by the shape of a grain elevator, the Canadian pavilion included Joseph-Émile Brunet's 28-foot sculpture of a buffalo (1937). Paintings by Brunet, sculpted panels on the outside of the structure, and several thematic stands inside the Canadian pavilion depicted aspects of Canadian culture.[3]

Spanish Pavilion

The Spanish pavilion attracted attention as the exposition took place during the Spanish Civil War. The Spanish pavilion was built by the Spanish architect Josep Lluis Sert.[4] The pavilion, set up by the Republican government, included Pablo Picasso's famous painting Guernica,[5] a depiction of the horrors of war, Alexander Calder's sculpture Mercury Fountain and Joan Miró's painting Catalan peasant in revolt.[6]

German Pavilion

Two of the other notable pavilions were those of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The organization of the world exhibition had placed the German and the Soviet pavilions directly across from each other.[7]Hitler had desired to withdraw from participation, but his architect Albert Speer convinced him to participate after all, showing Hitler his plans for the German pavilion. Speer later revealed in his autobiographies that he had had a clandestine look at the plans for the Soviet pavilion, and had designed the German pavilion to represent a bulwark against Communism.

The preparation and construction of the exhibits were plagued by delay. On the opening day of the exhibition, only the German and the Soviet pavilions had been completed. This, as well as the fact that the two pavilions faced each other, turned the exhibition into a competition between the two great ideological rivals.

Speer's pavilion was culminated by a tall tower crowned with the symbols of the Nazi state: an eagle and the swastika. The pavilion was conceived as a monument to "German pride and achievement". It was to broadcast to the world that a new and powerful Germany had a restored sense of national pride. At night, the pavilion was illuminated by floodlights. Josef Thorak's sculpture Comradeship stood outside the pavilion, depicting two enormous nude males, clasping hands and standing defiantly side by side, in a pose of mutual defense and "racial camaraderie".[7]

Map of the exhibition

Soviet Pavilion

The architect of the Soviet pavilion was Boris Iofan. Vera Mukhina designed the large figurative sculpture on the pavilion. The grand building was topped by Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, a large momentum-exerting statue, of a male worker and a female peasant, their hands together, thrusting a hammer and a sickle. The statue was meant to symbolize the union of workers and peasants.[7]

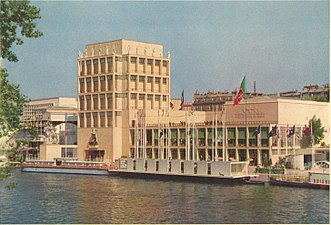

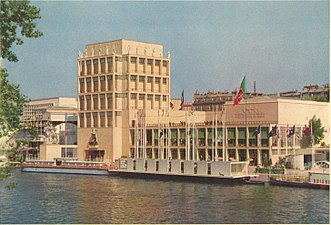

Italian Pavilion

Italy was vying for attention as one of three totalitarian nations: Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia presented themselves as great (and opposing) forces to be reckoned with. Italy was the benevolent dictatorship: sunny, open and Mediterranean it was founded on discipline, order and unity. Marcello Piacentini was given the job of designing the pavilion exterior. He used a modern reinforced concrete frame combined with traditional elements such as colonnades, terraces, courts and galleries, the tower form, Classical rhythms and the use of Mediterranean marble and stucco. The pavilion was nestled under the Eiffel tower looking out over the Seine to the main part of the Exposition site.

Giuseppe Pagano was responsible for the overall co-ordination of the exhibtis and was the first impact on entering the building, its large courtyard garden and its hall of honour. The main entry was through the Court of Honour that showcased life size examples of Italy’s most important contribution to the history of technology. Arturo Martini’s Victory of the Air presided over the space, her dark bronze form standing out against a seemingly infinite backdrop of blue-grey Venetian mosaic tiles. From there visitors could visit the Colonial Exhibits by Mario Sironi and the Gallery of Tourism before enjoying a plate of real spaghetti on the restaurant terrace. The courtyard garden was designed a respite from the exhibits with a symphony of green grass and green-glazed tiles set against red flowers and burgundy porphyry.

The Hall of Honour was the pavilion’s most dramatic and evocative space. It also ‘repurposed’ an existing artwork: Mario Sironi’s Corporative Italy (Fascist Work) mosaic from the 1936 Triennale that had now been completed with numerous figures engaged in different types of work and the figure of the imperial Roman eagle flying in from the right hand side. The 8m x 12 m work towered over the two-storey height space that occupied the top of the pavilion’s tower, making it the centre piece of the pavilion’s decorative and propaganda program. The enthroned figure of Italy represented Corporatism – the successful economic policy that merged the best of Capitalism and the best of Communism – and that had, up until then proved a success. The room was a celebration of all those aspects of Fascist society that Pagano wholeheartedly believed in: social harmony, government input to generate industrial innovation and support for artists, professionals and craftsmen as well as workers. Here Pagano had the joy of working alongside five different artists and placing Italy’s newest industrial material such as linoleum and Termolux (shatterproof plate glass) next to a sumptuous chandelier from Murano and amber marble.[8]

British Pavilion

Britain had not been expecting such a competitive exposition, and its planned budget was only a small fraction of Germany's.[9]Frank Pick, the chairman of the Council for Art and Industry, appointed Oliver Hill as architect but told him to avoid modernism and to focus on traditional crafts.[10] The main architectural element of Hill's pavilion was a large white box, decorated externally with a painted frieze by John Skeaping and internally with giant photographic figures which included Neville Chamberlain fishing. Its contents were crafts objects arranged according to English words which had become loanwords in French, such as "sport" and "weekend". There was considerable British criticism that the result was unrepresentative of Britain and compared poorly to the other pavilions' projections of national strength.[9]

Awards

- At the presentation, both Speer and Iofan, who also designed the Palace of Soviets that was planned to be constructed in Moscow, were awarded gold medals for their respective designs. Also, for his model of the Nuremberg party rally grounds, the jury granted Speer, to his and Hitler's surprise, a Grand Prix.[11]

- Artist Johanne deRibert Kajanus, mother of composer Georg Kajanus and film-maker Eva Norvind, granddaughter of composer and conductor Robert Kajanus, and grandmother of actress Nailea Norvind, won a bronze medal for her life-size sculpture of Mother and Child at the exhibition[citation needed].

- Polish engineers from Warsaw won a gold medal for the new Polish locomotive Pm36-1 PKP class Pm36[citation needed].

- American architect Alden Dow won the "grand prize for residential architecture" for his John S. Whitman House, built in Midland, Michigan, USA.[12]

- Soviet architect Andrey Kryachkov won the Grand Prix for designing his 100-flat building located in Novosibirsk.

- German textile designer, weaver and former Bauhaus student Margaretha Reichardt (1907-1984) won an honorary diploma for her Gobelin tapestry.[13]

Festivals of the Exposition

- 23 May — The Centenary of the Arc de Triomphe

- 5 – 13 June — The International Floralies

- 26 June — Motorboat races on the Seine

- 29 June — Dance Festival

- July[when?] — Midsummer Night's Dream (In the gardens of Bagatelle)

- 3 July — Horse Racing

- 4 – 11 July — Rebirth of the City

- 21 July — Colonial Festival

- 27 July — World Championship Boxing Matches

- 30 July – 10 August — The True Mystery of the Passion (before Notre Dame Cathedral)

- 12 September — Grape Harvest Festival

- 18 October Naissance du Cité – Birth of a City

- Forty Two International Sporting Championships

- Every Night: Visions of Fairyland on the Seine

Reproduction of the Soviet pavilion

After the Paris exhibition closed, Worker and Kolkhoz Woman was moved to the entrance of the All-Russia Exhibition Centre in Moscow, where it stood on a high platform. In 2007 the Russian government decided to create a reproduction of the Soviet pavilion, with the sculpture placed on top. This was inaugurated in 2009.[citation needed]

Gallery

The Nazi German pavilion

The Soviet pavilion

The Polish pavilion

The Swiss pavilion

The Romanian pavilion

The Soviet pavilion reproduced in Moscow

The Italian Pavilion

Entrance to the Italian Pavilion

(Colour reconstruction)

See also

- Nazi architecture

- Stalinist architecture

Streamline Moderne architecture

Further reading

World's Fairs on the Eve of War: Science, Technology, and Modernity, 1937-1942 by Robert H. Kargon and others, 2015, University of Pittsburgh Press

References

^ Magazines, Hearst (1 July 1933). "Popular Mechanics". Hearst Magazines. Retrieved 7 April 2018 – via Google Books..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Weidlinger, Tom. "THE PAVILION OF NEW TIMES". restlesshungarian.com. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

^ Evrard, Guillaume (2010) “Producing and Consuming Agricultural Capital: The Aesthetics and Cultural Politics of Grain Elevators at the 1937 Paris International Exposition” in Balfour, Robert J. (ed.) Culture, Capital and Representation. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 148-68

ISBN 978-0-230-29119-5

^ ...the Spanish Pavilion PBS. Retrieved 15 October 2012

^ Beevor, Antony. (2006). The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Penguin Books. London. p.249

^ http://www.bib.ub.edu/en/libraries/pavello-republica/expos/pavello-republica/ Archived 7 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

^ abc R. J. Overy (30 September 2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-02030-4.

^ F. Marcello, "Italians do it Better: Fascist Italy’s New Brand of Nationalism in the Art and Architecture of the Italian Pavilion, Paris 1937" in Rika Devos, Alexander Ortenberg, Vladimir Paperny eds., Architecture of Great Expositions 1937-1958: Reckoning with the Global War, Ashgate Press, 2015, 51-70.

^ ab Crinson, Mark (2004). "Architecture and 'national projection' between the wars". In Arnold, Dana. Cultural Identities and the Aesthetics of Britishness. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 191–194. ISBN 0-7190-6768-5.

^ Saler, Michael T. (1999). The Avant-Garde in Interwar England : Medieval Modernism and the London Underground. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-19-514718-9.

^ Fest, Joachim. Speer p.88 (English edition)

^ Robinson, Sidney K., ‘’The Architecture of Alden B. Dow, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, MI 1983 p. 45

^ Margaretha Reichardt. Bauhaus100. Available at: https://www.bauhaus100.de/en/past/people/students/margaretha-reichardt/ (Accessed: 27 November 2016)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne. |

- Official website of the BIE

Exposition internationale de 1937 at the Médiathèque de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine (French)

Exposition Internationale de 1937 Photographs

Exposition Internationale by Sylvain Ageorges (French)- Traces of the Exposition

- International Exposition of Arts and Technics in modern life