Paul the Deacon

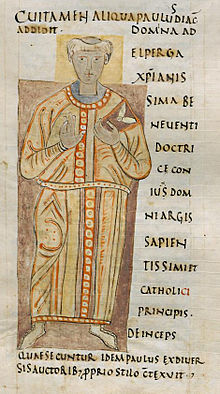

Depiction of Paulus Diaconus in a 10th-century manuscript (Laurentian Library Plut. 65.35 fol. 34r)

Paul the Deacon (c. 720s – 13 April 799 AD), also known as Paulus Diaconus, Warnefridus, Barnefridus, Winfridus and sometimes suffixed Cassinensis (i.e. "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, scribe, and historian of the Lombards.

Contents

1 Life

2 Works

3 Notes

4 References

5 Further reading

6 External links

Life

An ancestor named Leupichis entered Italy in the train of Alboin and received lands at or near Forum Julii (Cividale del Friuli). During an invasion, the Avars swept off the five sons of this warrior into Pannonia, but one, his namesake, returned to Italy and restored the ruined fortunes of his house. The grandson of the younger Leupichis was Warnefrid, who by his wife Theodelinda became the father of Paul.[1]

Paulus was his monastic name; he was born Winfrid, son of Warnefrid.

Born between 720 and 735 in the Duchy of Friuli to this possibly noble Lombard family, Paul received an exceptionally good education, probably at the court of the Lombard king Ratchis in Pavia, learning from a teacher named Flavian the rudiments of Greek. It is probable that he was secretary to the Lombard king Desiderius, a successor of Ratchis; it is certain that this king's daughter Adelperga was his pupil. After Adelperga had married Arichis II, duke of Benevento, Paul at her request wrote his continuation of Eutropius.[1]

It is certain that he lived at the court of Benevento, possibly taking refuge when Pavia was taken by Charlemagne in 774; but his residence there may be much more probably dated to several years before that event. Soon he entered a monastery on Lake Como, and before 782 he had become a resident at the great Benedictine house of Monte Cassino, where he made the acquaintance of Charlemagne. About 776 his brother Arichis had been carried as a prisoner to Francia, and when five years later the Frankish king visited Rome, Paul successfully wrote to him on behalf of the captive.[1]

His literary achievements attracted the notice of Charlemagne, and Paul became a potent factor in the Carolingian Renaissance. In 787 he returned to Italy and to Monte Cassino, where he died on 13 April in one of the years between 796 and 799. His surname Diaconus, shows that he took orders as a deacon; and some think he was a monk before the fall of the Lombard kingdom.[1]

Works

Paul's extant works are edited in Patrologia Latina vol. 95 (1861).[1]

The chief work of Paul is his Historia Langobardorum. This incomplete history in six books was written after 787 and at any rate no later than 795/96, maybe at Monte Cassino. It covers the story of the Lombards from their legendary origins in the north in 'Scadinavia' and their subsequent migrations, notably to Italy in 568/9 to the death of King Liutprand in 744, and contains much information about the Eastern Roman empire, the Franks, and others. The story is told from the point of view of a Lombard and is especially valuable for the relations between the Franks and the Lombards. It begins:[1]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The region of the north, in proportion as it is removed from the heat of the sun and is chilled with snow and frost, is so much the more healthful to the bodies of men and fitted for the propagation of nations, just as, on the other hand, every southern region, the nearer it is to the heat of the sun, the more it abounds in diseases and is less fitted for the bringing up of the human race.[1]

Among his sources, Paul used the document called the Origo gentis Langobardorum, the Liber pontificalis, the lost history of Secundus of Trent, and the lost annals of Benevento; he made a free use of Bede, Gregory of Tours and Isidore of Seville.[1]

Cognate with this work is Paul's Historia Romana, a continuation of the Breviarium of Eutropius. This was compiled between 766 and 771, at Benevento. The story runs that Paul advised Adelperga to read Eutropius. She did so, but complained that this Pagan writer said nothing about ecclesiastical affairs and stopped with the accession of the emperor Valens in 364; consequently Paul interwove extracts from the Scriptures, from the ecclesiastical historians and from other sources with Eutropius, and added six books, thus bringing the history down to 553. This work has value for its early historical presentation of the end of the Roman Empire in Western Europe, although it was very popular during the Middle Ages. It has been edited by H Droysen and published in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Auctores antiquissimi, Band ii. (1879)[1] as well as by A. Crivellucci, in Fonti per la storia d' Italia, n. 51 (1914).[2]

Paul wrote at the request of Angilram, bishop of Metz (d. 791), a history of the bishops of Metz to 766, the first work of its kind north of the Alps, translated in English in 2013 as Liber de episcopis Mettensibus. He also wrote many letters, verses and epitaphs, including those of Duke/Prince Arichis II of Benevento and of many members of the Carolingian family. Some of the letters are published with the Historia Langobardorum in the Monumenta; the poems and epitaphs edited by Ernst Dümmler will be found in the Poetae latini aevi carolini, Band i. (Berlin, 1881). Fresh material having come to light, a new edition of the poems (Die Gedichte des Paulus Diaconus) has been edited by Karl Neff (Munich, 1908),[3] who denies, however, the attribution to Paul of the most famous poem in the collection, the Ut queant laxis, a hymn to St. John the Baptist, which Guido d'Arezzo fitted to a melody which had previously been used for Horace's Ode 4.11.[4] From the initial syllables of the first verses of the resultant setting he then took the names of the first notes of the musical scale. Paul also wrote an epitome, which has survived, of Sextus Pompeius Festus' De verborum significatu. It was dedicated to Charlemagne.[5]

While in Francia, Paul was requested by Charlemagne to compile a collection of homilies. He executed this after his return to Monte Cassino, and it was largely used in the Frankish churches. A life of Pope Gregory the Great has also been attributed to him,[3] and he is credited with a Latin translation of the Greek Life of Saint Mary the Egyptian.[6]

Notes

^ abcdefghi Chisholm 1911, p. 964.

^ Paul the Deacon; Crivelluci, Amedeo, ed. "Pauli Diaconi Historia romana". WorldCat. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link) .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Chisholm 1911, p. 965.

^ Lyons 2007, p. [page needed].

^ Irvine, Martin (1994). The Making of Textual Culture: 'Grammatica' and Literary Theory 350-1100. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. p. 314. ISBN 978-0521031998. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

^ Donovan, Leslie A. (1999). Women Saints' Lives in Old English Prose. Cambridge: Brewer. p. 98. ISBN 978-0859915687. Retrieved 22 Aug 2016.

References

Lyons, Stuart (2007). Horace's Odes and the Mystery of Do-Re-Mi. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-0-85668-790-7.

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Paulus Diaconus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 964–965. Endnotes:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Paulus Diaconus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 964–965. Endnotes:

Carlo Cipolla, Note bibliografiche circa l'odierna condizione degli studi critici sul testo delle opere di Paolo Diacono (Venice, 1901)

Atti e memorie del congresso storico tenuto in Cividale (Udine, 1900)

Felix Dahn, Langobardische Studien, Bd. i. (Leipzig, 1876)

Wilhelm Wattenbach, Deutschlands Geschichtsquellen, Bd. i. (Berlin, 1904)

Albert Hauck, Kirchengeschichte Deutschlands, Bd. ii. (Leipzig, 1898)

Pasquale Del Giudice[it], Studi di storia e diritto (Milan, 1889)

Ugo Balzani, Le Cronache italiane nel medio evo (Milan, 1884)

Further reading

Goffart, Walter (1988). The Narrators of Barbarian History. Yale.

Paul the Deacon (2013). Liber de episcopis Mettensibus. Dallas Medieval Texts and Translations. 19. Translated by Kempf, Damien. Paris/Leuven/Walpole, MA: Peeters.

Schlager, Patricius (1911). "Paulus Diaconus". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Schlager, Patricius (1911). "Paulus Diaconus". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Christopher Heath {2017} The Narrative Worlds of Paul the Deacon: Between Empires and Identities in Lombard Italy [Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press}

External links

Wikisource has original works written by or about: Paul the Deacon |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paulus Diaconus. |

Works of Paulus Diaconus at Bibliotheca Augustana (in Latin)- History of the Lombards