Secretariat (horse)

| Secretariat | |

|---|---|

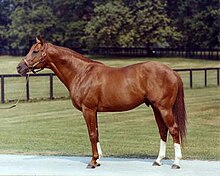

Secretariat as an older stallion | |

| Sire | Bold Ruler |

| Grandsire | Nasrullah |

| Dam | Somethingroyal |

| Damsire | Princequillo |

| Sex | Stallion |

| Foaled | March 30, 1970 The Meadow, Caroline County, Virginia |

| Died | October 4, 1989(1989-10-04) (aged 19) Claiborne Farm Paris, Kentucky |

| Country | United States |

| Color | Chestnut |

| Breeder | Meadow Stud (Christopher Chenery) |

| Owner | Meadow Stable (Christopher Chenery, Penny Chenery) |

| Racing colors | Blue, white blocks, white stripes on sleeves, blue cap |

| Trainer | Lucien Laurin |

| Record | 21: 16–3–1 |

| Earnings | $1,316,808[1] |

| Major wins | |

Triple Crown race wins: Kentucky Derby (1973) Preakness Stakes (1973) Belmont Stakes (1973) Graded Stakes wins: Sanford Stakes (1972) Hopeful Stakes (1972) Futurity Stakes (1972) Laurel Futurity (1972) Garden State Futurity (1972) Bay Shore Stakes (1973) Gotham Stakes (1973) Arlington Invitational (1973) Marlboro Cup (1973) Man o' War Stakes (1973) Canadian International (1973) | |

| Awards | |

9th U.S. Triple Crown Champion (1973) American Champion Two-Year-Old Colt (1972) American Champion Three-Year-Old Male Horse (1973) American Champion Male Turf Horse (1973) American Horse of the Year (1972, 1973) Leading broodmare sire in North America (1992) | |

| Honors | |

U.S. Racing Hall of Fame (1974) Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame (2007) Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame (2013) U.S. Postage Stamp (1999) #2 – Top 100 U.S. Racehorses of the 20th Century[2] | |

Secretariat (March 30, 1970 – October 4, 1989) was an American Thoroughbred racehorse who, in 1973, became the first Triple Crown winner in 25 years. His record-breaking victory in the Belmont Stakes, which he won by 31 lengths, is widely regarded as one of the greatest races of all time. During his racing career, he won five Eclipse Awards, including Horse of the Year honors at ages two and three. He was elected to the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1974. In the List of the Top 100 U.S. Racehorses of the 20th Century, Secretariat is second only to Man o' War (racing career 1919–1920), who also was a large chestnut colt given the nickname "Big Red".

At age two, Secretariat finished fourth in his 1972 debut in a maiden race, but then won seven of his remaining eight starts, including five stakes victories. His only loss during this period was in the Champagne Stakes, where he finished first but was disqualified to second for interference. He received the Eclipse Award for champion two-year-old colt, and also was the 1972 Horse of the Year, a rare honor for a horse so young. At age three, Secretariat not only won the Triple Crown, he set speed records in all three races. His time in the Kentucky Derby still stands as the Churchill Downs track record for 1 1⁄4 miles, and his time in the Belmont Stakes stands as the American record for 1 1⁄2 miles on the dirt. His controversial time in the Preakness Stakes was eventually recognized as a stakes record in 2012. Secretariat's win in the Gotham Stakes tied the track record for 1 mile, he set a world record in the Marlboro Cup at 1 1⁄8 miles, and further proved his versatility by winning two major stakes races on turf. He lost three times that year: in the Wood Memorial, Whitney, and Woodward Stakes, but the brilliance of his nine wins made him an American icon. He won his second Horse of the Year title, plus Eclipse Awards for champion three-year-old colt and champion turf horse.

At the beginning of his three-year-old year, Secretariat was syndicated for a record-breaking $6.08 million on condition that he be retired from racing by the end of the year. Although he sired several successful racehorses, he ultimately was most influential through his daughters' offspring, becoming the leading broodmare sire in North America in 1992. His daughters produced several notable sires, including Storm Cat, A.P. Indy, Gone West, Dehere and Chief's Crown, and through them Secretariat appears in the pedigree of many modern champions. Secretariat died in 1989 due to laminitis at age 19. He is recognized as one of the greatest horses in American racing history.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Early years

2 Appearance and conformation

3 Racing career

3.1 1972: Two-year-old season

3.2 1973: Three-year-old season

3.2.1 Kentucky Derby

3.2.2 Preakness Stakes

3.2.3 Belmont Stakes

3.2.4 Arlington Invitational

3.2.5 Whitney Stakes

3.2.6 Marlboro Cup

3.2.7 Woodward Stakes

3.2.8 Man o' War Stakes

3.2.9 Canadian International Stakes

4 Retirement

4.1 Stud career

4.2 Death

5 Honors and recognition

6 Racing statistics

7 Pedigree

8 Notes

9 References

10 Sources

11 External links

Background

Secretariat was officially bred by Christopher Chenery's Meadow Stud,[1] but the breeding was actually arranged by Penny Chenery (then known as Penny Tweedy), who had taken over the running of the stable in 1968 when her father became ill.[3] Secretariat was sired by Bold Ruler and his dam was Somethingroyal, a daughter of Princequillo. Bold Ruler was the leading sire in North America from 1963 to 1969 and again in 1973.[4] Owned by the Phipps family, Bold Ruler possessed both speed and stamina, having won the Preakness Stakes and Horse of the Year honors in 1957, and American Champion Sprint Horse honors in 1958.[5] Bold Ruler was retired to stud at Claiborne Farm, but the Phippses owned most of the mares to which Bold Ruler was bred, and few of his offspring were sold at public auction.[6] To bring new blood into their breeding program, the Phippses sometimes negotiated a foal-sharing agreement with other mare owners:[7] Instead of charging a stud fee for Bold Ruler, they would arrange for multiple matings with Bold Ruler, either with two mares in one year or one mare over a two-year period. Assuming two foals were produced, the Phipps family would keep one and the mare's owner would keep the other, with a coin toss determining who received first pick.[3][8]

Under such an arrangement, Chenery sent two mares to be bred to Bold Ruler in 1968, Hasty Matelda and Somethingroyal. She then sent Cicada and Somethingroyal in 1969. The foal-sharing agreement stated that the winner of the coin toss would get first pick of the foals produced in 1969, while the loser of the toss would get first pick of the foals due in 1970. In the spring of 1969, a colt and filly were produced. In the 1969 breeding season, Cicada did not conceive, leaving only one foal due in the spring of 1970. Thus, the winner of the coin toss would get only one foal (the first pick from 1969), and the loser would get two (the second pick from 1969 and the only foal from 1970). Chenery later said that both owners hoped they would lose the coin toss,[9] which was held in the fall of 1969 in the office of New York Racing Association Chairman Alfred G. Vanderbilt II, with Arthur "Bull" Hancock of Claiborne Farm as witness. Ogden Phipps won the toss and took the 1969 weanling filly out of Somethingroyal.[3][10] The filly was named The Bride and never won a race, though she did later become a stakes producer.[11][12] Chenery received the Hasty Matelda colt in 1969 and the as-yet-unborn 1970 foal of Somethingroyal, which turned out to be Secretariat.[3]

Early years

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%;max-width:100%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

And in the frosty morn

The horseman eyes him fondly,

And a secret hope is born.

But breathe it not, nor whisper

For fear of a neighbor's scorn.

He's a chestnut colt, and he's got a star.

He may be another Man o' War.

Nay, say it aloud – be shameless.

Dream and hope and yearn,

For there's never a man among you

But waits for his return.

—from "Big Red", by J.A. Estes[13][a]

On March 30, 1970, at 12:10 a.m. at the Meadow Stud in Caroline County, Virginia, Somethingroyal foaled a bright-red chestnut colt with three white socks and a star with a narrow stripe. The foal stood when he was 45 minutes old and nursed 30 minutes later. Howard Gentry, the manager of Meadow Stud, was at the foaling and later said, "He was a very well-made foal. He was as perfect a foal that I ever delivered."[16] The colt soon distinguished himself from the others. "He was always the leader in the crowd," said Gentry's nephew, Robert, who also worked at the farm. "To us, he was Big Red, and he had a personality. He was a clown and was always cutting up, always into some devilment."[17] Some time later, Chenery got her first look at the foal and made a one word entry in her notebook: "Wow!"[18]

That fall, Chenery and Elizabeth Ham, the Meadow's longtime secretary, worked together to name the newly weaned colt. The first set of names submitted to the Jockey Club (Sceptre, Royal Line, and Something Special) played on the names of his sire and dam, but were rejected. The second set, submitted in January 1971, were Games of Chance, Deo Volente ("God Willing"), and Secretariat, the last suggested by Ham based on her previous job associated with the secretariat of the League of Nations (the predecessor of the United Nations).[11][19][20]

Appearance and conformation

Equine anatomy

Secretariat grew into a massive, powerful horse said to resemble his sire's maternal grandsire, Discovery. He stood 16.2 hands (66 inches, 168 cm) when fully grown.[21] He was noted for being exceptionally well-balanced, described as having "nearly perfect" conformation and stride biomechanics.[22] His chest was so large that he required a custom-made girth, and he was noted for his large, powerful, well-muscled hindquarters. An Australian trainer said of him, "He is incredible, an absolutely perfect horse. I never saw anything like him."[23]

Secretariat's absence of major conformation flaws was important, as horses with well made limbs and feet are less likely to become injured.[24] Secretariat's hindquarters were the main source of his power, with a sloped croup that extended the length of his femur.[25] When in full stride, his hind legs were able to reach far under himself, increasing his drive.[26] His ample girth, long back and well-made neck all contributed to his heart-lung efficiency.[25][26]

The manner in which Secretariat's body parts fit together determined the efficiency of his stride, which affected his acceleration and endurance. Even very small differences in the length and angles of bones can have a major effect on performance.[27] Secretariat was well put together even as a two-year-old, and by the time he was three, he had further matured in body and smoothed out his gait. The New York Racing Association's Dr. M. A. Gilman, a veterinarian who routinely measured leading Thoroughbreds with a goal of applying science to create better ways to breed and evaluate racehorses, measured Secretariat's development from two to three as follows:[23][28]

| Measurement | October aged 2 | October aged 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Height (at withers) | 16 3⁄4 hands (64.75 inches, 164 cm) | 16.1 1⁄2 hands (65.5 inches, 166 cm) |

| Point of shoulder to point of shoulder (chest width) | 16 inches (41 cm) | 16.5 inches (42 cm) |

| Girth (around center of gravity) | 74 inches (188 cm) | 76 inches (193 cm) |

| Withers to point of shoulder | 28 inches (71 cm) | 28.5 inches (72 cm) |

Elbow to ground (length of leg) | 37.5 inches (95 cm) | 38.5 inches (98 cm) |

| Point of shoulder to point of hip | 46 inches (117 cm) | 49 inches (124 cm) |

| Point of hip to point of hip | 25 inches (64 cm) | 26 inches (66 cm) |

| Point of hip to hock | 40 inches (100 cm) | 40 inches (100 cm) |

| Point of hip to buttock | 24 inches (61 cm) | 24 inches (61 cm) |

Poll to withers (neck length) | 40 inches (100 cm) | 40 inches (100 cm) |

| Buttock (croup) to ground (height in rear) | 53.5 inches (136 cm) | 55.5 inches (141 cm) |

| Point of shoulder to point of buttock (body length) | 68 inches (173 cm) | 69.5 inches (177 cm) |

| Circumference of cannon under knee | 8.25 inches (21.0 cm) | 8.5 inches (22 cm) |

Secretariat's length of stride was considered large even after taking into account his large frame and strong build.[22] While training for the Preakness Stakes, his stride was measured as 24 feet, 11 inches.[29] His powerful hindquarters allowed him to unleash "devastating" speed and because he was so well-muscled and had significant cardiac capacity, he could simply out-gallop competitors at nearly any point in a race.[22]

His weight before the Gotham Stakes in April 1973 was 1,155 pounds (524 kg).[30] After completing the grueling Triple Crown, his weight on June 15 had dropped only 24 pounds, to 1,131 pounds (513 kg).[23] Secretariat was known for his appetite — during his three-year-old campaign, he ate 15 quarts of oats a day — and to keep the muscle from turning to fat, he needed fast workouts that could have won many a stakes race.[31]

Seth Hancock of Claiborne Farm once said,

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"You want to know who Secretariat is in human terms? Just imagine the greatest athlete in the world. The greatest. Now make him six-foot-three, the perfect height. Make him real intelligent and kind. And on top of that, make him the best-lookin' guy ever to come down the pike. He was all those things as a horse."[32]

Racing career

Racing colors of Meadow Stable

Secretariat raced in Meadow Stables' blue-and-white-checkered colors. He never raced in track bandages, but typically wore a blinker hood, mostly to help him focus, but also because he had a tendency to run in towards the rail during races.[23] In January 1972, he joined trainer Lucien Laurin's winter stable at Hialeah. Secretariat gained a reputation as a kind horse, likeable and unruffled in crowds or by the bumping that occurs between young horses. He had the physique of a runner, but at first was awkward and clumsy. He was frequently outpaced by more precocious stable mates, running a quarter-mile in 26 seconds compared to 23 seconds by his peers.[33] His regular exercise riders were Jim Gaffney and Charlie Davis. Davis was not initially impressed. "He was a big fat sucker", Davis said. "I mean, he was big. He wasn't in a hurry to do nothin'. He took his time. The quality was there, but he didn't show it until he wanted to."[34] Gaffney though recalled his first ride on Secretariat in early 1972 as "having this big red machine under me, and from that very first day I knew he had a power of strength that I have never felt before ..."[35]

Groom Eddie Sweat was another important member of the Secretariat team, providing most of the daily hands-on care. Sweat once told a reporter, "I guess a groom gets closer to a horse than anyone. The owner, the trainer, they maybe see him once a day. But I lived with him, worked with him."[36]

Laurin sent Chenery regular updates on Secretariat's progress, saying that the colt was still learning to run, or that he still needed to lose his baby fat.[33][37] Chenery recalled that when Secretariat was in training, Lucien once said: "Your big Bold Ruler colt don't show me nothin'. He can't outrun a fat man."[38] But Secretariat made steady progress over the spring. On June 6, he wore blinkers for the first time to keep his attention focused and responded with a half-mile workout in a solid 473⁄5 seconds. On June 24, he ran a "bullet", the fastest workout of the day, at 6 furlongs in 1:124⁄5 on a sloppy track. Laurin called Chenery at her Colorado home and advised her that Secretariat was ready to race.[39]

1972: Two-year-old season

For his first start on July 4, 1972 at Aqueduct Racetrack, Secretariat was made the lukewarm favorite at 3–1. At the start, a horse named Quebec cut in front of the field, causing a chain reaction that resulted in Secretariat being bumped hard. According to jockey Paul Feliciano, he would have fallen if he hadn't been so strong. Secretariat recovered, only to run into traffic on the backstretch. In tenth position at the top of the stretch, he closed ground rapidly and finished fourth, beaten by only 1 1⁄4 lengths.[32][40] In many of his subsequent races, Secretariat hung back at the start, which Laurin later attributed to the bumping he received in his debut.[41]

With Feliciano again up, Secretariat returned to the track on July 15 as the 6–5 favorite. He broke poorly, but then rushed past the field on the turn to win by six lengths.[42] On July 31 in an allowance race at Saratoga, Feliciano was replaced by Ron Turcotte, the regular jockey for Meadow Stables. Turcotte had ridden the colt in several morning workouts, but had missed his first two starts while recovering from a fall. Secretariat's commanding win as the 2–5 favorite[43] caught the attention of veteran sportswriter, Charles Hatton. He later reported, "You carry an ideal around in your head, and boy, I thought, 'This is it.' I never saw perfection before. I absolutely could not fault him in any way. And neither could the rest of them and that was the amazing thing about it. The body and the head and the eye and the general attitude. It was just incredible. I couldn't believe my eyes, frankly."[37]

In August, Secretariat entered the Sanford Stakes, facing off with highly regarded Linda's Chief. Entering the stretch, Secretariat was blocked by the horses in front of him but then made his way through "like a hawk scattering a barnyard of chickens"[26] on his way to a three-length win. Sportswriter Andrew Beyer covered the race for the Washington Star and later wrote, "Never have I watched a lightly raced 2-year-old stamp himself so definitively as a potential great."[44]

Ten days later in the Hopeful Stakes, Secretariat made a "dazzling" move, passing eight horses within 1⁄4 mile to take the lead then drawing off to win by five lengths.[45] His time of 1:161⁄5 for 6 1⁄2 furlongs was only 3⁄5 of a second off the track record.[46] Returning to Belmont Park on September 16, he won the Belmont Futurity by a length and a half after starting his move on the turn. He then ran in the Champagne Stakes at Belmont on October 14 as the 7–10 favorite.[42] As had become his custom, he started slowly and then made a big move around the turn, blowing past his rivals to win by two lengths. However, following an inquiry by the racecourse stewards, Secretariat was disqualified and placed second for bearing in and interfering with Stop the Music, who was declared the winner.[47]

Secretariat then took the Laurel Futurity on October 28, winning by eight lengths over Stop the Music. His time on a sloppy track was just 1⁄5 of a second off the track record.[48] He completed his season in the Garden State Futurity on November 18, dropping back early and making a powerful move around the turn to win by 3 1⁄2 lengths at 1–10 odds. Laurin said, "In all his races, he has taken the worst of it by coming from behind, usually circling his field. A colt has to be a real runner to do this consistently and get away with it."[49]

Secretariat won the Eclipse Award for American Champion Two-Year-Old Male Horse and, in a rare occurrence, two two-year-olds topped the balloting for 1972 American Horse of the Year honors, with Secretariat edging out the undefeated filly, La Prevoyante. Secretariat received the votes of the Thoroughbred Racing Associations of North America and the Daily Racing Form, while La Prevoyante was chosen by the National Turf Writers Association.[50][51] Only one horse since then, Favorite Trick in 1997, has won that award as a two-year-old.[52]

1973: Three-year-old season

In January 1973, Christopher Chenery, the founder of Meadow Stables, died and the taxes on his estate forced his daughter Penny to consider selling Secretariat. Together with Seth Hancock of Claiborne Farm, she instead managed to syndicate the horse, selling 32 shares worth $190,000 each for a total of $6.08 million, a world syndication record at the time, surpassing the previous record for Nijinsky who was syndicated for $5.44 million in 1970.[53] Hancock said the sale was easy, citing Secretariat's two-year-old performance, breeding, and appearance. "He's, well, he's a hell of a horse." Chenery retained four shares in the horse and would have complete control over his three-year-old racing campaign, but agreed that he would be retired at the end of the year.[41]

Secretariat wintered in Florida but did not race until March 17, 1973 in the Bay Shore Stakes at Aqueduct, where he went off as the heavy favorite. As the trainer of one of his opponents put it, "The only chance we have is if he falls down."[41] Racing boxed in by horses on each side, Turcotte decided to go through a narrow gap between horses rather than try to circle the field. Secretariat broke free and won easily, but one of the other jockeys claimed that Secretariat had committed a foul going through the hole. The stewards reviewed photos from the race and determined that Secretariat was actually on the receiving end of a bump, so let the result stand.[54] The Bay Shore established that Secretariat had improved over the winter and that he could also handle adversity.[55]

In the Gotham Stakes on April 7, Laurin decided to experiment with Secretariat's running style. With no speed horses entered in the race, Secretariat would be allowed to set his own pace. Accordingly, Turcotte hustled Secretariat from the starting gate and they led easily. Down the stretch though, Champagne Charlie came running and at the eighth pole was almost even. Turcotte tapped Secretariat once on each side with the whip and Secretariat drew away to win by three lengths. He ran the first 3/4 mile in 1:083⁄5 and finished the one-mile race in 1:332⁄5, matching the track record.[30]

His final preparatory race for the Kentucky Derby was the Wood Memorial, where he finished a surprising third to Angle Light and Santa Anita Derby winner Sham. Laurin was crushed, even though he had trained the winner, Angle Light, who set a slow pace and "stole" the race.[55] Secretariat's loss was later attributed to a large abscess in his mouth, which made him sensitive to the bit.[32] Before and after the race, there was some ill feeling between Laurin and the trainer of Sham, Pancho Martin, fanned by comments in the press. The dispute concerned the use of coupled entries[b] as Martin had entered two horses in addition to Sham, all with the same owner. There was fear that an entry could be used tactically to gang up on another horse. Stung by such insinuations, Martin wound up scratching the two horses that he had originally entered with Sham, and asked Lauren to do the same, but Laurin could not follow suit as Secretariat and Angle Light had different owners.[57]

Because of the Wood Memorial results, Secretariat's chances in the Kentucky Derby became the subject of much speculation in the media.[58] Some questioned his stamina: in part because of his "blocky" build, more typical of a sprinter, and in part because of Bold Ruler's reputation as a sire of precocious sprinters.[59] Rumors circulated that Secretariat was unsound.[32]

Kentucky Derby

The 1973 Kentucky Derby on May 5 attracted a crowd of 134,476 to Churchill Downs, then the largest crowd in North American racing history.[60] The bettors made the entry of Secretariat and Angle Light the 3–2 favorite, with Sham the second choice at 5–2. The start was marred when Twice a Prince reared in his stall, hitting Our Native, positioned next to him, and causing Sham to bang his head against the gate, loosening two teeth. Sham then broke poorly and cut himself, also bumping into Navajo. Secretariat avoided problems by breaking last from post position 10, then cut over to the rail. Early leader Shecky Greene set a reasonable pace, then gave way to Sham around the far turn. Secretariat came charging as they entered the stretch and battled with Sham down the stretch, finally pulling away to win by 2 1⁄2 lengths. Our Native finished eight lengths further back in third.[61][62]

Secretariat at the Derby

On his way to a still-standing track record of 1:592⁄5,[63] Secretariat ran each quarter-mile segment faster than the one before it. The successive quarter-mile times were :251⁄5, :24, :234⁄5, :232⁄5, and :23.[32] This means he was still accelerating as of the final quarter-mile of the race.[21] No other horse had won the Derby in less than 2 minutes before, and it would not be accomplished again until Monarchos ran the race in 1:59.97 in 2001.[64]

Sportswriter Mike Sullivan later said:

I was at Secretariat's Derby, in '73 ... That was ... just beauty, you know? He started in last place, which he tended to do. I was covering the second-place horse, which wound up being Sham. It looked like Sham's race going into the last turn, I think. The thing you have to understand is that Sham was fast, a beautiful horse. He would have had the Triple Crown in another year. And it just didn't seem like there could be anything faster than that. Everybody was watching him. It was over, more or less. And all of a sudden there was this, like, just a disruption in the corner of your eye, in your peripheral vision. And then before you could make out what it was, here Secretariat came. And then Secretariat had passed him. No one had ever seen anything run like that – a lot of the old guys said the same thing. It was like he was some other animal out there.[65]

Preakness Stakes

Secretariat in the winner's circle after the Preakness, with Ron Turcotte, Lucien Lauren, Eddie Sweat and Penny Chenery (then Tweedy)

In the 1973 Preakness Stakes on May 19, Secretariat broke last, but then made a huge, last-to-first move on the first turn. Raymond Woolfe, a photographer for the Daily Racing Form, captured Secretariat launching the move with a leaping stride in the air. This was later used as the basis for the statue by John Skeaping that stands in the Belmont Park paddock.[66] Turcotte later said that he was proudest of this win because of the split-second decision he made going into the turn: "I let my horse drop back, when I went to drop in, they started backing up into me. I said, 'I don't want to get trapped here.' So I just breezed by them."[67] Secretariat completed the second quarter mile of the race in under 22 seconds.[31] After reaching the lead with 5 1⁄2 furlongs to go, Secretariat was never challenged, and won by 2 1⁄2 lengths, with Sham again finishing second and Our Native in third, a further eight lengths back. It was the first time in history that the top three finishers in the Derby and Preakness were the same; the distance between each of the horses was also the same.[68]

The time of the race was disputed. The infield teletimer displayed a time of 1:55 but it had malfunctioned because of damage caused by people crossing the track to reach the infield. The Pimlico Race Course clocker E.T. McLean Jr. announced a hand time of 1:542⁄5, but two Daily Racing Form clockers claimed the time was 1:532⁄5, which would have broken the track record of 1:54 set by Cañonero II. Tapes of Secretariat and Cañonero II were played side by side by CBS, and Secretariat got to the finish line first on tape, though this was not a reliable method of timing a horse race at the time. The Maryland Jockey Club, which managed the Pimlico racetrack and is responsible for maintaining Preakness records, discarded both the electronic and Daily Racing Form times and recognized the clocker's 1:542⁄5 as the official time; however, the Daily Racing Form, for the first time in history, printed its own clocking of 1:532⁄5 underneath the official time in the chart of the race.[66][68][69][70]

On June 19, 2012, a special meeting of the Maryland Racing Commission was convened at Laurel Park at the request of Penny Chenery, who hired companies to conduct a forensic review of the videotapes of the race. After over two hours of testimony, the commission unanimously voted to change the time of Secretariat's win from 1:542⁄5 to 1:53, establishing a new stakes record. The Daily Racing Form announced that it would honor the commission's ruling with regard to the running time.[69] With the revised time, Sham also would have broken the old stakes record.[66]

As Secretariat prepared for the Belmont Stakes, he appeared on the covers of three national magazines: Time, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated. He had become a national celebrity.[45] William Nack wrote: "Secretariat suddenly transcended horse racing and became a cultural phenomenon, a sort of undeclared national holiday from the tortures of Watergate and the Vietnam War."[32]

Chenery needed a secretary to handle all the fan mail and hired the William Morris Agency to manage public engagements.[16] Secretariat responded to his fame by learning to pose for the camera.[71][72]

Belmont Stakes

Only four horses ran against Secretariat for the June 9 Belmont Stakes, including Sham and three other horses thought to have little chance by the bettors: Twice A Prince, My Gallant, and Private Smiles. With so few horses in the race, and Secretariat expected to win, no "show" bets were taken. Secretariat was sent off as a 1–10 favorite[73] before a crowd of 69,138, then the second largest attendance in Belmont history.[74] The race was televised by CBS and was watched by over 15 million households, an audience share of 52%.[75]

— Charles Hatton

On race day, the track was fast, and the weather was warm and sunny.[73] Secretariat broke well on the rail and Sham rushed up beside him. The two ran the first quarter in a quick :233⁄5 and the next quarter in a swift :223⁄5, completing the fastest opening half mile in the history of the race and opening ten lengths on the rest of the field. After the six-furlong mark, Sham began to tire, ultimately finishing last. Secretariat continued the fast pace and opened up a larger and larger margin on the field. His time for the mile was 1:341⁄5, over a second faster than the next fastest Belmont mile fraction in history, set by his sire Bold Ruler, who had eventually tired and finished third. Secretariat, however, did not falter. Turcotte said, "This horse really paced himself. He is smart: I think he knew he was going 1 1⁄2 miles, I never pushed him."[77] In the stretch, Secretariat opened a lead of almost 1⁄16 of a mile on the rest of the field. At the finish, he won by 31 lengths, breaking the margin-of-victory record set by Triple Crown winner Count Fleet in 1943 of 25 lengths.[76]

CBS Television announcer Chic Anderson described the horse's pace in a famous commentary:

Secretariat is widening now! He is moving like a tremendous machine![78][76]

The time for the race was not only a record, it was the fastest 1 1⁄2 miles on dirt in history, 2:24 flat, breaking the stakes record by more than two seconds.[76] Secretariat's record still stands as an American record on the dirt.[79] If the Beyer Speed Figure calculation had been developed during that time, Andrew Beyer calculated that Secretariat would have earned a figure of 139, the highest he has ever assigned.[44][80]

A large crowd had started gathering around the paddock hours before the Belmont, many missing the races run earlier in the day for a chance to see the horses up close. Secretariat and Chenery were greeted with an enthusiasm that Chenery responded to with a wave or smile;[81] Secretariat was imperturbable. A large cheer went up at the break, but as the race went on, the two most commonly reported reactions were disbelief and fear that Secretariat had gone too fast.[32][81][82][83] When it was clear that Secretariat would win, the sound reached a crescendo that reportedly made the grandstand shake.[71]The Blood-Horse magazine editor Kent Hollingsworth described the impact: "Two twenty-four flat! I don't believe it. Impossible. But I saw it. I can't breathe. He won by a sixteenth of a mile! I saw it. I have to believe it."[81]

The race is widely considered the greatest performance of the twentieth century by a North American racehorse.[82][84][85] Secretariat became the ninth Triple Crown winner in history, and the first since Citation in 1948, a gap of 25 years.[86] Bettors holding 5,427 winning parimutuel tickets on Secretariat never redeemed them, presumably keeping them as souvenirs (and because the tickets would have paid only $2.20 on a $2 bet).[87]

Arlington Invitational

Three weeks after his win at Belmont, Secretariat was shipped to Arlington Park for the Arlington Invitational. Laurin explained: "Even before the Belmont, you remember, I said I really didn't know how I could give this horse a rest. He's so strong and full of energy. Well, this is only a week and a half after the Belmont, and believe me when I tell you, if I don't run this horse he's going to hurt himself in his stall. So we decided it would be nice to race him in Chicago to let the people in the Midwest have a chance to see him run." The race was run at 1 1⁄8 miles with a purse of $125,000. The challengers were grouped as a single betting entry at 6–1: Secretariat was 1–20 (the legal minimum) and created a minus pool of $17,941.[88]

Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago declared that the Saturday of the race was Secretariat Day. A crowd of 41,223 (the largest at Arlington in three decades) greeted his arrival on the track with sustained applause. Secretariat broke poorly but soon went to the lead, setting slow early fractions. He gathered momentum on the final turn and eventually won by nine lengths in 1:47 flat, just 1⁄5 off the track record set by Damascus.[88]George Plimpton commented, "With a better start, a horse to press him and less bow to his turns, Secretariat might have posted a time that would have stood a century."[89]

Whitney Stakes

Secretariat next went to Saratoga, popularly nicknamed "the graveyard of champions", in preparation for the Whitney Stakes on August 4, where he would face older horses the first time. On July 27, he put in a stunning workout of 1:34 for a mile on a sloppy track, a time that would have broken Saratoga's track record. On race day though, he was beaten by the Allen Jerkens-trained Onion, a four-year-old gelding who had set a track record at 6 1⁄2 furlongs in his previous start. The track condition for the Whitney was labelled fast but was running slow, especially along the inside rail. Secretariat broke poorly and Onion led from the start, setting a slow pace running well off the rail. Down the backstretch, Turcotte chose to make his move along the rail rather than sweeping wide. Secretariat responded more sluggishly than usual and Turcotte went to the whip. Secretariat closed to within a head on the final turn before Onion pulled ahead in the straight to win by a length.[90] A record crowd of more than 30,000 witnessed what was described as an "astonishing" upset.[91]

Despite Jerkens's reputation as the "Giant Killer," Secretariat's stunning loss can possibly be attributed to a viral infection, which caused a low-grade fever and diarrhea. "I was learning then that anything could happen in horse racing," said Chenery. "We knew he had a low-grade infection. But we decided he was strong enough to win anyway, and we were wrong."[92]

Secretariat lost his appetite and acted sluggishly for several days.[93] Charles Hatton wrote: "He seemed distressingly ill walking off, and he missed the Travers. Returned to Belmont to point for the $250,000 Marlboro, the sport's pin-up horse looked bloody awful, rather like one of those sick paintings which betoken an inner theatre of the macabre. It required supernatural recuperative powers to recover as he did. He was subjected to four severe preps in two weeks. Astonishingly, he gained weight and blossomed with every trial."[23]

Marlboro Cup

On September 15, Secretariat returned to Belmont Park in the inaugural Marlboro Cup, which was originally intended to be a match race with stablemate Riva Ridge, the 1972 Derby and Belmont Stakes winner. After Secretariat's loss in the Whitney, the field was expanded to invite top horses from across the country.[94] Entries included 1972 turf champion and top California stakes winner Cougar II, Canadian champion Kennedy Road, 1972 American champion three-year-old colt Key to the Mint, Travers winner Annihilate 'Em (the only other three-year-old in the race), and Onion. Riva Ridge was assigned top weight of 127 pounds (one pound over the weight-for-age scale), Key to the Mint and Cougar II were at 126 pounds, scale weight, while Secretariat was at 124, three pounds over scale for his age. The field included five champions, and the seven starters had won 63 stakes races between them.[95]

It rained the night before, but the track dried out by race time. Secretariat stalked a fast pace in fifth, while Riva Ridge rated just behind Onion and Kennedy Road. Around the turn, Secretariat raced wide and started to make up ground. Coming into the stretch, Secretariat overtook Riva Ridge, while the other early leaders dropped back. Secretariat drew away to win, completing 1 1⁄8 miles in 1:45 2⁄5, then a world record on the dirt for the distance. Riva Ridge ran second with Cougar II in third and Onion in fourth. Turcotte said, "Today he was the old Secretariat and he did it on his own."[96] The purse for the Marlboro Cup was $250,000, then the highest prize money offered: the win made Secretariat the 13th Thoroughbred millionaire in history.[97][98]

Woodward Stakes

After the Marlboro Cup, the original plan was to enter Riva Ridge in the 1 1⁄2 mile Woodward Stakes, just two weeks later, while Secretariat put in some slow workouts on the turf in preparation for the Man o' War Stakes in October. It rained before the Woodward and the track was sloppy, which Riva Ridge could not handle, so Secretariat was entered in his place. Secretariat led into the straight but was overtaken by the Allen Jerkens-trained four-year-old Prove Out, who pulled clear to win by 4 1⁄2 lengths despite carrying five more pounds than Secretariat under the weight-for-age conditions of the race. Prove Out ran the race of his life that day: his time was the second-fastest mile-and-a-half on the dirt in Belmont Park's history despite the sloppy conditions.[93][99] Prove Out went on to beat Riva Ridge in that year's Jockey Club Gold Cup.[100]

Man o' War Stakes

On October 8, just nine days after the Woodward, Secretariat was moved to turf for the Man O' War Stakes at a distance of 1 1⁄2 miles. He faced Tentam, who had set a world record for 1 1⁄8 miles on the turf earlier that summer, and five others. Secretariat went to the lead early, followed by Tentam, who gradually closed the gap down the backstretch. Tentam got to within a half-length before Secretariat responded, pulling away by three lengths. Tentam made another run around the far turn, but Secretariat again drew away eventually winning by five lengths over Tentam, with Big Spruce seven and a half lengths further back in third. Secretariat set a course record time of 2:244⁄5. After the race, Ron Turcotte explained that "when Tentam came up to him in the backstretch I just chirped to him and he pulled away."[101]

Canadian International Stakes

The syndication deal for Secretariat precluded the horse racing past age three. Accordingly, Secretariat's last race was against older horses in the Canadian International Stakes over one and five-eighths miles on the turf at Woodbine Racetrack in Toronto, Ontario, Canada on October 28, 1973. The race was chosen in part because of long-time ties between E.P. Taylor and the Chenery family,[102] and partly to honor Secretariat's Canadian connections, Laurin and Turcotte.[103] Unfortunately, Turcotte missed the race with a five-day suspension: Eddie Maple got the mount.[104]

The day of the race was cold, windy and wet, but the Marshall turf course was firm. Despite the weather, some 35,000 people turned out to greet Secretariat in a "virtual hysteria" that Secretariat seemed not to notice. His biggest opponents were Kennedy Road, whom he had already beaten in the Marlboro Cup, and Big Spruce, who had finished third in the Man o' War. Kennedy Road went to the early lead, while Secretariat moved to second after breaking from an outside post. On the backstretch, Secretariat made his move and forged to the lead. "Snorting steam in the raw twilight",[105] he rounded the far turn with a 12-length lead before gearing down in the final furlong, ultimately winning by 6 1⁄2 lengths.[106] Once again, many winning tickets went uncashed by souvenir hunters.[103]

After the race, Secretariat was brought to Aqueduct Racetrack where he was paraded with Turcotte dressed in the Meadow silks before a crowd of 32,990 in his final public appearance. "It's a sad day, and yet it's a great day," said Laurin. "I certainly wish he could run as a 4-year-old. He's a great horse and he loves to run."[107]

Altogether, Secretariat won 16 of his 21 career races, with three seconds and one third, and total earnings of $1,316,808.[1]

For 1973, Secretariat was again named Horse of the Year, and won Eclipse Awards as the American Champion Three-Year-Old Male Horse and the American Champion Male Turf Horse.[108]

Retirement

Stud career

When Secretariat first retired to Claiborne Farm, his sperm showed some signs of immaturity,[23] so he was bred to three non-Thoroughbred mares in December 1973 to test his fertility. One of these, an Appaloosa named Leola, produced Secretariat's first foal in November 1974. Named First Secretary, the foal was a chestnut like his sire, but spotted like his dam.[109]

Secretariat's first official foal crop, arriving in 1975, consisted of 28 foals, the best of which was Dactylographer, who won the William Hill Futurity in October 1977.[110] The first crop also included Canadian Bound, who at the 1976 Keeneland July sale was the first yearling to break the $1 million barrier, selling for $1.5 million. Canadian Bound, however, was a complete failure in racing,[111] and for several years, the value of Secretariat's offspring declined considerably, especially given the rising popularity of Northern Dancer's offspring in the sales ring.[112]

Secretariat eventually sired a number of major stakes winners, including:[21]

General Assembly, winner of the 1979 Travers Stakes, setting a track record of 2:00 flat that stood for 37 years.[113][114]

Lady's Secret, 1986 Horse of the Year.[115]

Risen Star, 1988 Preakness and Belmont Stakes winner.[116]

Kingston Rule, 1990 Melbourne Cup winner, breaking the course record.[117]

Tinners Way, born in 1990 to Secretariat's last crop, winner of the 1994 and 1995 Pacific Classic.[118]

Ultimately, Secretariat officially sired 663 named foals, including 341 winners (51.4%) and 54 stakes winners (8.1%) .[119] There has been some criticism of Secretariat as a stallion, mainly because he did not produce male offspring of his own ability and did not leave a leading sire son behind, but his legacy is assured though the quality of his daughters, several of whom were excellent racers and even more of whom were excellent producers. In 1992, Secretariat was the leading broodmare sire in North America. Overall, Secretariat's daughters produced 24 Grade/Group 1 winners.[110] As a broodmare sire, Secretariat's most notable progeny were:[21][110]

Weekend Surprise, a stakes winner and the 1992 Kentucky Broodmare of the Year. Her sons include 1990 Preakness winner Summer Squall and 1992 Horse of the Year A.P. Indy.[120]

Terlingua, a stakes winner and dam of leading sire Storm Cat.[121]

Secrettame, a stakes winner and dam of important sire Gone West, whose descendants include Kentucky Derby winner Smarty Jones.[122]

- Six Crowns, dam of champion two-year-old and sire Chief's Crown.[123]

- Sister Dot, dam of champion two-year-old and sire Dehere.[124]

- Celtic Assembly, dam of Volksraad, leading sire in New Zealand.[125]

- Betty's Secret, dam of Secreto, winner of The Derby, and Istabraq, three-time winner of the Champion Hurdle.[126]

Through Weekend Surprise and Terlingua alone, Secretariat appears in the pedigree of numerous champions. Weekend Surprises's son A.P. Indy was the leading sire in North America in 2003 and 2006, and is the sire of 2003 Horse of the Year Mineshaft and 2007 Belmont Stakes winner Rags to Riches. He has also established a successful sire-line that leads to Kentucky Derby winners Orb and California Chrome.[127] A.P. Indy's leading sire-line descendant is Tapit, who led the sire list in 2014–2015 and is the sire of Belmont Stakes winners Tonalist and Creator.[128] Terlingua's son Storm Cat is also a two time leading sire, whose offspring include Giant's Causeway, three-time leading sire in North America.[129] Storm Cat also sired Yankee Gentleman, who is the broodmare sire of 2015 Triple Crown winner American Pharoah.[130] Both Storm Cat and A.P. Indy appear in the pedigree of 2018 Triple Crown winner Justify.[131]

Inbreeding to Secretariat has also proven successful, as exemplified by numerous graded stakes winners, including two-time Horse of the Year Wise Dan, as well as sprint champion Speightstown.[132]

Secretariat's paddock at Claiborne Farm bordered three other stallions: Drone, Sir Ivor, and Hall of Fame inductee Spectacular Bid. Secretariat did not pay much attention to Drone or Sir Ivor, but he and Spectacular Bid became friendly and occasionally raced each other along the fence line between their paddocks.[133][134]

Death

In the fall of 1989, Secretariat became afflicted with laminitis—a painful and debilitating hoof condition. When his condition failed to improve after a month of treatment, he was euthanized on October 4 at the age of 19.[32] Secretariat was buried at Claiborne Farm,[135] given the rare honor of being buried whole (traditionally only the head, heart, and hooves of a winning race horse are buried).[38]

At the time of Secretariat's death, the veterinarian who performed the necropsy, Dr. Thomas Swerczek, head pathologist at the University of Kentucky, did not weigh Secretariat's heart, but stated, "We just stood there in stunned silence. We couldn't believe it. The heart was perfect. There were no problems with it. It was just this huge engine."[32] Later, Swerczek also performed a necropsy on Sham, who died in 1993. Swerczek did weigh Sham's heart, and it was 18 pounds (8.2 kg). Based on Sham's measurement, and having necropsied both horses, he estimated Secretariat's heart probably weighed 22 pounds (10.0 kg), or about 2.5 times that of the average horse (8.5 pounds (3.9 kg)).[136]

An extremely large heart is a trait that occasionally occurs in Thoroughbreds, hypothesized to be linked to a genetic condition, called the "x-factor", passed down in specific inheritance patterns.[136][137][138] The x-factor can be traced to the historic racehorse Eclipse, who was necropsied after his death in 1789. Because Eclipse's heart appeared to be much larger than the hearts of other horses, it was weighed, and found to be 14 pounds (6.4 kg), almost twice the normal weight. Eclipse is believed to have passed the trait on via his daughters, and pedigree research verified that Secretariat traces his dam line to a daughter of Eclipse. Secretariat's success as a broodmare sire has been linked by some to this large heart theory.[136] However, it has not been proven whether the x-factor exists, let alone if it contributes to athletic ability.[139][140]

Honors and recognition

The Secretariat statue at Belmont Park is modeled after Secretariat's leaping stride during the Preakness.[66]

Secretariat was inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1974, the year following his Triple Crown victory.[141] Also in 1974, Paul Mellon commissioned a bronze statue, sometimes known as Secretariat in Full Stride, from John Skeaping. The life-size statue remained in the center of the walking ring at Belmont Park until 1988 when it was replaced by a replica.[142] The original is now located at the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame.[143] The Kentucky Horse Park has two other life-sized statues of Secretariat. The first, created by Jim Reno in 1992, shows Secretariat as an older sire, while the second, completed by Edwin Bogucki in 2004, shows him being led into the winner's circle after the Kentucky Derby.[144] In 2015, a new statue of Secretariat and Ron Turcotte crossing the finish line at the Belmont Stakes was unveiled in Grand Falls, New Brunswick, Turcotte's hometown.[145]

In 1994, Sports Illustrated ranked Secretariat #17 in their list of the 40 greatest sports figures of the past 40 years.[31] In 1999, ESPN listed him 35th of the 100 greatest North American athletes of the 20th century, the highest of three non-humans on the list (the other two were also racehorses: Man o' War at 84th and Citation at 97th).[146] Secretariat ranked second behind Man o' War in The Blood-Horse's List of the Top 100 U.S. Racehorses of the 20th Century.[2][147] He was also ranked second behind Man o' War by both a six-member panel of experts assembled by the Associated Press,[148] and a Sports Illustrated panel of seven experts.[149]

On October 16, 1999 in a ceremony conducted in the winner's circle at Keeneland Race Course in Lexington, the U.S. Postal Service honored Secretariat with a 33-cent postage stamp bearing his image.[150][151] In 2005, Secretariat was featured in ESPN Classic's show "Who's No. 1?" in the episode "Greatest Sports Performances". He was the only nonhuman on the list, with his run at Belmont ranking second behind Wilt Chamberlain's 100-point game.[152] On May 2, 2007, Secretariat was inducted into the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame, marking the first time an animal received this honor.[153] In 2013, Secretariat was inducted into the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame in honor of his victory in the Canadian International 40 years earlier.[102] Secretariat was also the focus of a 2013 segment of 60 Minutes Sports.[84] In March 2016, Secretariat's Triple Crown victory was rated #13 in the Sports Illustrated listing of the 100 Greatest Moments in Sports History.[154]

Due to Secretariat's enduring popularity, Chenery remained a prominent figure in racing and a powerful advocate for Thoroughbred aftercare and veterinary research until her death in 2017.[155][156] In 2004, the Maker's Mark Secretariat Center, dedicated to reschooling former racehorses and matching them to new homes, opened at the Kentucky Horse Park.[157] In 2010, Chenery developed the Secretariat Vox Populi ("voice of the people") Award, which is voted for by racing fans. It is intended to acknowledge "the horse whose popularity and racing excellence best resounded with the American public and gained recognition for Thoroughbred racing."[158] The consideration of the racing fan's engagement is what distinguishes the Vox Populi award from others. The first honoree in 2010 was Zenyatta, that year's Horse of the Year, while the second award went to Rapid Redux, a former claimer who went on to win 22 consecutive races at smaller racetracks.[159] Paynter received the 2012 award for his battle with laminitis, the same condition that led to Secretariat's death. "Paynter's popularity stems from his ability to battle and exceed expectations, making him the perfect choice as the recipient of this year's Vox Populi Award", said Chenery. "After seeing firsthand the devastating effects of this disease, I am even more convinced that the industry must continue to diligently fight laminitis. The progress we have made to date clearly benefited Paynter — a beautiful colt with a tremendous spirit."[158]

The Secretariat Stakes was created in 1974 to honor his appearance at Arlington Park in 1973.[160] The Meadow, the farm at which he was born, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is now known as The Meadow Historic District.[161]

Secretariat, a Disney live-action film about the racing career of Secretariat, written by Mike Rich and directed by Randall Wallace, was released on October 8, 2010.[162]

In the animated series BoJack Horseman, BoJack looked up to Secretariat as a child and would go on to star in a biopic about him. Margo Martindale, who plays herself in a recurring role on the show, also had a role in the Disney film Secretariat mentioned above.

Racing statistics

| Date | Age | Distance* | Race | Track | Odds | Field | Finish | Time | Margin | Jockey | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jul 4, 1972 | 2 | 5 1⁄2 furlongs | Maiden Special Weight | Aqueduct | 3.10 | 12 | 4 | 1:05 | (1 1⁄2) lengths | Paul Feliciano | [42][163] |

Jul 15, 1972 | 2 | 6 furlongs | Maiden Special Weight | Aqueduct | 1.30 | 11 | 1 | 1:10 3⁄5 | 6 lengths | Paul Feliciano | [42][163] |

Jul 31, 1972 | 2 | 6 furlongs | Allowance | Saratoga | 0.40 | 7 | 1 | 1:10 4⁄5 | 1 1⁄2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [42][163] |

Aug 16, 1972 | 2 | 6 furlongs | Sanford Stakes | Saratoga | 1.50[c] | 5 | 1 | 1:10 | 3 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [42][163] |

Aug 26, 1972 | 2 | 6 1⁄2 furlongs | Hopeful Stakes | Saratoga | 0.30 | 9 | 1 | 1:16 1⁄5 | 5 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [42][163] |

Sep 16, 1972 | 2 | 6 1⁄2 furlongs | Futurity Stakes | Belmont | 0.20 | 7 | 1 | 1:16 2⁄5 | 1 3⁄4 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [42][163] |

Oct 14, 1972 | 2 | 1 mile | Champagne Stakes | Belmont | 0.70 | 12 | 2[d] | 1:35 | 2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [42][163] |

Oct 28, 1972 | 2 | 1 1⁄16 mile | Laurel Futurity | Laurel | 0.10 | 6 | 1 | 1:42 4⁄5 | 8 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [42][163] |

Nov 18, 1972 | 2 | 1 1⁄16 mile | Garden State | Garden State | 0.10 | 6 | 1 | 1:44 2⁄5 | 3 1⁄2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Mar 17, 1973 | 3 | 7 furlongs | Bay Shore Stakes | Aqueduct | 0.20 | 6 | 1 | 1:23 1⁄5 | 4 1⁄2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Apr 7, 1973 | 3 | 1 mile | Gotham Stakes | Aqueduct | 0.10 | 6 | 1 | 1:33 2⁄5[e] | 3 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Apr 21, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄8 miles | Wood Memorial | Aqueduct | 0.30 | 8 | 3 | 1:49 4⁄5 | (4) lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

May 5, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄4 miles | Kentucky Derby | Churchill Downs | 1.50 | 13 | 1 | 1:59 2⁄5[f] | 2 1⁄2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [70][163][165] |

May 19, 1973 | 3 | 1 3⁄16 miles | Preakness Stakes | Pimlico | 0.30 | 6 | 1 | 1:54 2⁄5[g] | 2 1⁄2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [70][163][166] |

June 9, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄2 miles | Belmont Stakes | Belmont | 0.10 | 5 | 1 | 2:24 [h] | 31 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [70][163][167] |

June 30, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄8 miles | Arlington Invitational | Arlington | 0.05 | 4 | 1 | 1:47 | 9 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Aug 4, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄8 miles | Whitney Stakes | Saratoga | 0.10 | 5 | 2 | 1:49 1⁄5 | (1) lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Sep 15, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄8 miles | Marlboro Cup | Belmont | 0.40 | 7 | 1 | 1:45 2⁄5[i] | 3 1⁄2 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [70][163] |

Sep 29, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄2 miles | Woodward Stakes | Belmont | 0.30 | 5 | 2 | 2:25 4⁄5 | (4 1⁄2) lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Oct 8, 1973 | 3 | 1 1⁄2 miles (turf) | Man o' War Stakes | Belmont | 0.50 | 7 | 1 | 2:24 4⁄5[j] | 5 lengths | Ron Turcotte | [163][164] |

Oct 28, 1973 | 3 | 1 5⁄8 miles (turf) | Canadian International | Woodbine | 0.20 | 12 | 1 | 2:41 4⁄5 | 6 1⁄2 lengths | Eddie Maple | [106][163][164] |

| Furlongs | Miles | Meters |

|---|---|---|

| 5 1⁄2 | 11⁄16 | 1,106 |

| 6 | 3⁄4 | 1,207 |

| 6 1⁄2 | 13⁄16 | 1,308 |

| 7 | 7⁄8 | 1,408 |

| 8 | 1 | 1,609 |

| 8 1⁄2 | 1 1⁄16 | 1,710 |

| 9 | 1 1⁄8 | 1,811 |

| 9 1⁄2 | 1 3⁄16 | 1,911 |

| 10 | 1 1⁄4 | 2,012 |

| 12 | 1 1⁄2 | 2,414 |

| 13 | 1 5⁄8 | 2,615 |

| Year | Age | Starts | Win (1st) | Place (2nd) | Show (3rd) | Earnings ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 1 | — | 456,404[169] |

| 1973 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 860,404[169] |

Total | 21 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 1,316,808[1] | |

Secretariat's earnings in 1973 were, at the time, a single-season record.[23]

Pedigree

Secretariat was sired by Bold Ruler, who led the North America sire list eight times, more than any other stallion in the 20th century. He also led the juvenile (two-year-old) sire list a record six times. Before Secretariat's Triple Crown run, Bold Ruler was often categorized as a sire of precocious juveniles that lacked stamina or did not train on past age two.[170] However, even before Secretariat, Bold Ruler actually had sired 11 stakes winners of races at 10 furlongs or more.[171] Ultimately, seven of the ten Kentucky Derby winners in the 1970s can be traced directly to Bold Ruler in their tail male lines, including Secretariat and fellow Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew.[172]

Secretariat's dam was Somethingroyal, the 1973 Kentucky Broodmare of the Year. Although Somethingroyal was unplaced in her only start, she had an excellent pedigree. Her sire Princequillo was the leading broodmare sire from 1966 to 1970 and was noted as a source of stamina and soundness.[173] Her dam Imperatrice was a stakes winner who was purchased by Christopher Chenery at a dispersal sale in 1947 for $30,000. Imperatrice produced several stakes winners and stakes producers for the Meadow. Prior to foaling Secretariat at age 18, Somethingroyal had already produced Sir Gaylord, a stakes winner who became an important sire, whose offspring included Epsom Derby winner Sir Ivor. Somethingroyal's other stakes winners were First Family, Sir Gaylord and Syrian Sea.[174][175]

Breeders speak of a 'nick" occurring when a sire or grandsire produces significantly better offspring from the daughters of one particular sire than with mares from other bloodlines. The breeding of Bold Ruler with Somethingroyal is an example of a famous nick between Bold Ruler's sire Nasrullah and daughters of Princequillo. The goal was to balance the speed, precocity, and fiery temperament provided by the Nasrullah side of the pedigree with Princequillo's stamina, soundness, and sensible temperament.[176]

| Sire Bold Ruler dkb/br. 1954 | Nasrullah b. 1940 | Nearco b. 1932 | Pharos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nogara | |||

| Mumtaz Begum | Blenheim | ||

Mumtaz Mahal | |||

| Miss Disco b. 1944 | Discovery | Display | |

| Ariadne | |||

| Outdone | Pompey | ||

| Sweep Out | |||

| Dam Somethingroyal b. 1952 | Princequillo b. 1940 | Prince Rose | Rose Prince |

| Indolence | |||

| Cosquilla | Papyrus | ||

| Quick Thought | |||

| Imperatrice dkb/br. 1938 | Caruso | Polymelian | |

| Sweet Music | |||

| Cinquepace | Brown Bud | ||

| Assignation (Family 2-s)[178] |

Notes

^ Man o' War, like Secretariat, was known as "Big Red."[14] The poem was quoted by Edward L. Bowen in "Joining the Giants", an article in The Blood-Horse magazine about Secretariat's Belmont win. The article's author added a footer to the poem, "Perhaps the wait has ended," in reference to Secretariat.[13] The author of the poem, Joe Estes, joined The Blood-Horse in 1930 and became its editor-in-chief.[15]

^ An "entry" or "coupled entry" is when multiple horses with the same owner or trainer are grouped together for betting purposes. A bet on the entry cashes in if either horse wins.[56]

^ The Sanford was the only race in his career in which Secretariat was not the betting favorite[42][163]

^ Finished first, disqualified to second

^ Equaled track record

^ New track record

^ This was the official time until revisited in 2012 when it was adjusted to 1:53, a stakes record (see section above for details)

^ New track record. American record on the dirt,[79] though this was not noted on the chart

^ Then a world record on dirt. Still stands as the track record[168]

^ Then a course record

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Secretariat. |

^ abcd "Profile – Secretariat". Equibase. Retrieved June 27, 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Duke, p. 14

^ abcd Christine, Bill (September 30, 2010). "Penny Chenery's life, unscripted". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ Peters, Anne; Erigero, Patricia. "Leading Sires of the U.S.A". Thoroughbred Heritage. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

^ Peters, Anne (March 28, 2014). "The Influence of Bold Ruler". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

^ Tower, Whitney (February 22, 1965). "Bold is the Badge of Champions". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Hall, Tom (February 1, 1998). "Foal Sharing". The Horse. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Nack, p.41

^ Woolfe, p.10

^ Woolfe, pp. 9–12

^ ab "Chenery, Christopher T. (1886–1973)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

^ "The Bride". Pedigree Online Thoroughbred Database. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

^ ab "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 39

^ Schwartz, Larry. "Man o' War came close to perfection". ESPN. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

^ Bowen, Edward (February 20, 2016). "BH 100: Instant Classic". Blood-Horse. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

^ ab Glauber, Bill (May 2, 1993). "'It Was Like He Was Flying': In Five Weeks in 1973, Secretariat Went From a Potentially Great Horse to a Racing Legend". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ "Gentry Shares Life on Farm with Secretariat". bluefield.edu. February 18, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ Woolfe, p. 25

^ Nack, p. 49

^ Lusky, Leonard. "Ask Penny". secretariat.com. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

^ abcd Hunter, Avalyn. "Secretariat (horse)". American Classic Pedigrees. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ abc Mitchell, p. 93–94

^ abcdefg Illman, Dan (September 23, 2010). "Secretariat, Charles Hatton, HandiGambling pp's". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ Tate, James (July 10, 2008). "Is Conformation Relevant?". Trainer Magazine. Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

^ ab "Secretariat: Horsegears conformation analysis". Horsegears. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

^ abc Hatton, Charles (March 8, 2012). "Secretariat: Hatton on the 1972 season (from the 1972 American Racing Manual)". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Horsegears Racehorse Conformation Gears Theory". Horsegears. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

^ Mitchell, pp. 83–84

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 28

^ ab "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 5

^ abc Nack, William (September 19, 1994). "17 Secretariat". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

^ abcdefghi Nack, William (June 4, 1990). "Pure Heart". Sports Illustrated Longform. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ ab Nack, pp. 66-7

^ Hiers, Fred (June 4, 2010). "Secretariat's exercise rider reflects on champion horse". Ocala StarBanner. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ Jeansonne, John (June 3, 2010). "Jim Gaffney, exercise rider for Secretariat, dead at 75". Newsday. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ Scanlan, Lawrence (2008). "Prologue". The horse God built: the untold story of Secretariat, the world's greatest racehorse (1st U.S. ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-38225-4.

^ ab Wirth, Jennifer (September 22, 2010). "Secretariat: the beauty of being everything". Blood-Horse. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

^ ab Moss, Josh (April 2007). "Stride for Stride with Big Red". Louisville Magazine. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Nack, pp. 77–78

^ Woolfe, pp. 41–45

^ abc Putnam, Pat (March 26, 1973). "Oh Lord, He's Perfect". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

^ abcdefghijk Woolfe, front end papers

^ Woolfe, pp. 47–48

^ ab Beyer, Andrew (October 7, 2010). "'Secretariat' introduces extraordinary horse to a new generation". Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

^ ab Keane, Patrick J. (September 6, 2015). "Secretariat: A Personal Memoir". Numéro Cinq. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ Woolfe, p. 51

^ Canadian Press (October 16, 1972). "Stop the Music wins disqualification". Calgary Herald. p. 27. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Woolfe, p. 59

^ Tower, Whitney (November 27, 1972). "Thorns among the roses". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

^ "La Prevoyante or Secretariat, Horse of the Year 1972". Colin's Ghost: Thoroughbred Horse Racing History. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Cady, Steve (December 27, 1972). "Secretariat Is Horse of Year, Topping La Prevoyante in Poll". New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

^ Porter, Alan. "Trick's Pic Reinforces Nick". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

^ "Secretariat Is Syndicated For Record $6.08‐Million". New York Times. February 27, 1973. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 3

^ ab Haskin, Steve (January 21, 2013). "Big Red and the Winter of '73". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

^ "Industry Glossary". Equibase. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 6

^ Capps, Timothy T. (2003). Secretariat (1st ed.). Lexington, KY: Eclipse Press. p. 121. ISBN 1-58150-091-2.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 14

^ Tower, Whitney (May 14, 1973). "It was murder". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, pp. 12, 14

^ "Secretariat charges past Sham in Kentucky Derby win". Herald-Journal. Associated Press. May 6, 1973. p. B1. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ "Track Records – Churchill Downs". Churchill Downs. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

^ Drape, Joe (May 6, 2001). "Monarchos Makes His Point and Roars to Victory in the Derby". New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Sullivan, John Jeremiah (2004). Blood horses : notes of a sportswriter's son. New York, NY: Picador. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-312-42376-6.

^ abcd Haskin, Steve (June 20, 2012). "Viva Big Red!". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

^ Jerardi, Dick (June 5, 2008). "Jockey looks back at Secretariat's 1973 Triple Crown". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ ab "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 32

^ ab Hegarty, Matt (June 19, 2012). "Secretariat awarded Preakness record at 1:53 after review". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

^ abcde Woolfe, p.192

^ ab Haskin, Steve (June 4, 2012). "Remembering Big Red". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

^ Christine, Bill (October 5, 1989). "Secretariat Was Champion of the People, Both Young and Old". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ ab "Secretariat: A Triple Terror". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. June 10, 1973. p. D1. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ Nichols, Joe (June 9, 1973). "This Day In Sports – A Horse for the Ages". New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

^ "Roundtable Discussion of the Jockey Club (1973)" (PDF). Jockey Club. p. 16. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

^ abcd Flatter, Ron. "Secretariat remains No. 1 name in racing". ESPN. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 40

^ "This day in history: June 9, 1973". Vancouver Sun. June 11, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

^ ab "North American Records". Equibase. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "Daily Racing Form: Beyer Numbers". Daily Racing Form. Archived from the original on July 7, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

^ abc Hollingsworth, Kent (June 18, 1973). "Triple Crown Heroes: Secretariat". Blood-Horse. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

^ ab Tower, Whitney (June 18, 1973). "History in the Making". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

^ Woolfe, pp. 121–122

^ ab Cohen, Andrew (June 7, 2013). "Secretariat's Jockey on Winning the Triple Crown at Belmont, 40 Years Ago". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

^ Cherwa, John (June 5, 2015). "Ranking the Triple Crown winners". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ "Triple Crown Winners". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ "Souvenir hunters failing to cash in on triple crown winner". Observer-Reporter. July 11, 1973. p. B3. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ ab "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 47

^ Plimpton, George (July 9, 1973). "Crunch went the Big Red Apple". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, pp. 49–50

^ "Secretariat beaten!". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. August 5, 1973. p. B1. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ Hovdey, Jay (August 2, 2013). "The day Onion slayed". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

^ ab Haskin, Steve (August 4, 2008). "The Unbeatable Horse". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 51

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, pp. 52–53

^ Tower, Whitney (September 24, 1973). "They made pigeons of the field". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 55

^ Sekulic, Mike (September 23, 2013). "Marlboro Cup of Champions". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

^ "Prove Out beats Secretariat". Pittsburgh Press. September 30, 1973. p. D14. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 62

^ "Another purse to Secretariat". Calgary Herald. October 9, 1973. p. 17. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ ab "Secretariat – Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame". Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

^ ab Perkins, Dave (October 15, 2010). "Secretariat one of a kind". Toronto Star. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 63

^ Deford, Frank. "Adieu, Adieu, Kind Friends". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

^ ab "A Look Back", Blood-Horse, p. 64

^ Nichols, Joe (November 7, 1973). "A Ceremonial Windup for Secretariat". New York Times. p. 35. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

^ "Triple Crown winner Secretariat sweeps Horse of the Year ballotting". Montreal Gazette. Associated Press. December 19, 1973. p. 29. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ Illman, Dan (February 7, 2011). "Top Beyers, Secretariat's First Foal, Arlington Pars". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ abc "Secretariat – great sire or a dud at stud?". Sporting Post. April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ "A Memorable Date: First Seven-Figure Yearling Sold". Blood-Horse. July 20, 2006. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Schmitz, David (July 15, 2001). "Era Ends With Mr. Prospector's Last Foal Crop". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

^ Beyer, Andrew (August 19, 1979). "General Assembly Shows His Heels". Washington Post. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ "Baffert Reflects on Arrogate's Travers Romp". Blood-Horse. August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

^ Oakford, Glenye Cain (September 17, 2011). "Lady's Secret dead at age 21". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

^ Crist, Steven (June 12, 1988). "Risen Star Runs Away with the Belmont". New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

^ "Melbourne Cup Winner Kingston Rule Dies". Blood-Horse. December 8, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Schmitz, David (September 14, 2010). "Tinners Way Retired to Old Friends". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Hunter, Avalyn. "Secretariat (horse)". American Classic Pedigrees. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

^ "Kentucky Broodmare of the Year Weekend Surprise Dead". Blood-Horse. March 4, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ "Terlingua, Storm Cat's Dam, Dead". Blood-Horse. April 29, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Peters, Anne (January 30, 2015). "The Legacy of Gone West". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ "Six Crowns, Dam of Champion Chief's Crown, Dies at Age 26". Blood-Horse. February 15, 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Hammonds, Evan (May 16, 2014). "Champion Dehere Dead at 23 in Turkey". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ "Volksraad Wins Third New Zealand Sire Title". Blood-Horse. August 26, 2004. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Oppenheim, Bill (February 27, 2003). "The Royal Ascot of Jumping" (PDF). Thoroughbred Daily News. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

^ Reed, Patrick (August 22, 2013). "Hot Sire: A.P. Indy". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Russo, Nicole (June 13, 2016). "Tapit in familiar spot atop sires list". Daily Racing Form. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Hunter, Avalyn. "Giant's Causeway (horse)". American Classic Pedigrees. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ Hunter, Avalyn (June 26, 2015). "Triple Crown Connections". Blood-Horse. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

^ "Pedigree of Justify". www.equineline.com. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

^ Hunter, Avalyn (November 1, 2013). "Inbreeding to Secretariat: Not a Passing Fad". Blood-Horse. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

^ Crist, Steven (April 17, 1984). "Secretariat, at 14, is still a star". New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

^ Toepfer, Susan; Shaw, Bill (June 13, 1988). "After 15 Years of Foaling Around, Superhorse Secretariat Fathers a Big Winner". People. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

^ Embry, Mike (October 5, 1989). "Secretariat, Suffering From Incurable Condition, Destroyed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

^ abc Haun, Marianna (January 25, 2012). "The X Factor: The Heart of the Matter". HorsesOnly.com. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ Haun, Marianna (1996). The x factor : what it is & how to find it : the relationship between inherited heart size and racing performance. Neenah, WI: Russell Meerdink Co. ISBN 978-0-929346-46-5.

^ Lowitt, Bruce (December 19, 1999). "Secretariat proves he's a unique breed". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

^ Porter, Alan (September 11, 2009). "Q & A -- Can the 'X-Factor' be Incorporated in TrueNicks Pedigrees?". True Nicks. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

^ "The X-Factor Theory". Sophia Stallions. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

^ "Secretariat – National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame". National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Roberts, Paul; Taylor, Isabelle; Weatherly, Laurence (January 4, 2015). "The stamp of greatness: Thoroughbred legends in sculpture". Thoroughbred Racing Commentary. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

^ ""Secretariat" by John Skeaping – National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame". National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

^ "Equestrian Sculpture – Horse Sculptures – Kentucky Horse Park". Kentucky Horse Park. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

^ "Secretariat's jockey touched by hometown tribute". CBC. July 20, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

^ "Top North American athletes of the century". ESPN. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Ross, Scott (April 18, 2013). "Horse of the Century: Man o' War vs. Secretariat". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

^ "Man o'War voted best of 20th Century". ESPN. The Associated Press. December 22, 1999. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

^ Reed, William (October 27, 1992). "Then & Now 30 Years Ago 'the Best I Ever Rode'". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

^ United States Postal Service (October 16, 1999). "Regal Thoroughbred Rides Into History When U.S Postal Service Commemorates Secretariat". PR Newswire. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ "1999 Stamp Program". USPS.com. October 7, 2008. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

^ Hengler, Greg (October 5, 2010). "Secretariat: Why He's One Of ESPN's Greatest Athletes Of All Time". townhall.com. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

^ McAninch, Kelly (March 29, 2007). "Secretariat first equine to enter Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame". Thoroughbred Times. Retrieved February 11, 2018.