Bosra

Bosra بصرى بصرى الشام | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Busra al-Sham | |

The centre of Bosra | |

Bosra Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 32°31′N 36°29′E / 32.517°N 36.483°E / 32.517; 36.483Coordinates: 32°31′N 36°29′E / 32.517°N 36.483°E / 32.517; 36.483 | |

| Grid position | 289/214 |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Daraa |

| District | Daraa |

| Subdistrict | Bosra |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 19,683 |

| • Religions | Sunni Muslim Shia Muslim (minority) |

| Area code(s) | 15 |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Ancient City of Bosra |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, vi |

| Reference | 22 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

| Area | 116.2 ha |

| Buffer zone | 200.4 ha |

Bosra (Arabic: بصرى, translit. Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially known Busra al-Sham (Arabic: بصرى الشام, translit. Buṣrā al-Shām, Turkish: Busra el-Şam)[1] is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Daraa District of the Daraa Governorate and geographically being part of the Hauran region.

According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Bosra had a population of 19,683 in the 2004 census. It is the administrative center of the nahiyah ("subdistrict") of Bosra which consisted of nine localities with a collective population of 33,839 in 2004.[2] Bosra's inhabitants are predominantly Sunni Muslims, although the town has a small Shia Muslim community.[3]

Bosra has an ancient history and during the Roman era it was a prosperous provincial capital and Metropolitan Archbishopric, under the jurisdiction of Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East. It continued to be administratively important during the Islamic era, but became gradually less prominent during the Ottoman era. It also became a Latin Catholic titular see and the episcopal see of a Melkite Catholic Archeparchy. Today, it is a major archaeological site and has been declared by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Roman and Byzantine era

1.2 Islamic era

1.3 Ottoman era

1.4 Modern era

2 Ecclesiastical history

2.1 Titular see

3 Main sights

4 Climate

5 Demographics

6 Notable people from Bosra

7 Gallery

8 References

9 Bibliography

10 Further reading

11 Sources and external links

History

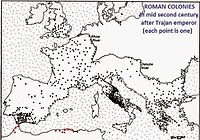

The settlement was first mentioned in the documents of Thutmose III and Akhenaten (14th century BC). Bosra was the first Nabatean city in the 2nd century BC. The Nabatean Kingdom was conquered by Cornelius Palma, a general of Trajan, in 106 AD.

Roman and Byzantine era

The Roman Theatre at Bosra, dating from the 2nd century AD

Roman mosaic from Bosra displaying a camel train

Under the Roman Empire, Bosra was renamed Nova Trajana Bostra and was the residence of the legio III Cyrenaica. It was made capital of the Roman province of Arabia Petraea. The city flourished and became a major metropolis at the juncture of several trade routes, namely the Via Traiana Nova, a Roman road that connected Damascus to the Red Sea. It became an important center for food production and during the reign of Emperor Philip the Arab, Bosra began to mint its own coins.[4] The two Councils of Arabia were held at Bosra in 246 and 247 AD.

By the Byzantine period which began in the 5th-century, Christianity became the dominant religion in Bosra. The city became a Metropolitan archbishop's seat (see below) and a large cathedral was built in the sixth century.[4] Bosra was conquered by the Sasanian Persians in the early seventh century, but was recaptured during a Byzantine reconquest.

Islamic era

Bosra played an important part in the early life of Muhammad, as described in the entry for the Christian monk Bahira. The forces of the Rashidun Caliphate under general Khalid ibn Walid captured the city from the Byzantines in the Battle of Bosra in 634. Throughout Islamic rule, Bosra would serve as the southernmost outpost of Damascus, its prosperity being mostly contingent on the political importance of that city. Bosra held additional significance as a center of the pilgrim caravan between Damascus and the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina, the destinations of the annual hajj pilgrimage.[5] Early Islamic rule did not alter the general architecture of Bosra, with only two structures dating to the Umayyad era (721 and 746) when Damascus was the capital of the Caliphate. As Bosra's inhabitants gradually converted to Islam the Roman-era holy sites were utilized for Muslim practices.[6] In the 9th-century Ya'qubi wrote that Bosra was the capital of the Hauran province.[7]

A view of the citadel in Bosra (the theater is located inside)

After the end of the Umayyad era in 750, major activity in Bosra ceased for around 300 years until the late 11th-century. In the last years of Fatimid rule, in 1068, a number of building projects were commissioned. With the advent of Seljuk rule in 1076, increasing focus was paid to Bosra's defenses. In particular, the Roman theater was transformed into a fortress, with a new floor added to the interior staircase tower.[6] With the coming to power of the Burid dynasty in Damascus, the general Kumushtakin was allotted the entire Hauran plain as a fief by the atabeg Tughtakin. Under Kumushtakin, efforts to enhance the Muslim nature of the city increased with the construction of a number of Islamic edifices. Of these projects was the restoration of the Umari Mosque, which had been built by the Umayyads in 721.[6] Another mosque commissioned was the smaller al-Khidr Mosque built at the northwestern part of the city, which was established under Kumushtakin, in 1134. Kumushtakin also had a madrasa constructed alongside the Muslim shrine honoring the mabrak an-naqa ("camel's knees"), which marked the imprints of the camel the prophet Muhammad rode on when he entered Bosra in the early 7th-century.[8]

A golden age of political and architectural activity in Bosra began during the reign of Ayyubid sultan al-Adil I (1196–1218). One of the first architectural developments in the city was the construction of eight large external towers in the Roman theater-turned-fortress. The project began in 1202 and were completed in 1253, towards the end of the Ayyubid period. The two northern corner towers alone occupied more space than the remaining six. After al-Adil's death in 1218, his son as-Salih Ismail inherited the fief of Bosra who resided in its newly fortified citadel. During Ismail's rule, Bosra gained political prominence. Ismail used the city as his base when he claimed the sultanate in Damascus on two separate occasions, reigning between 1237–38 and 1239–45.[9]

Ottoman era

In 1596 Bosra appeared in the Ottoman tax registers as Nafs Busra, being part of the nahiyah of Bani Nasiyya in the Qada of Hauran. It had a Muslim population consisting of 75 households and 27 bachelors, and a Christian population of 15 households and 8 bachelors. Taxes were paid on wheat, barley, summer crops, fruit- or other trees, goats and/or beehives and water mill.[10]

Modern era

Today, Bosra is a major archaeological site, containing ruins from Roman, Byzantine, and Muslim times, its main feature being the well preserved Roman theatre. Every year there is a national music festival hosted in the main theatre.

Significant social and economic changes have affected Bosra since the end of the French Mandate in 1946. While up until the 1950s the shopkeepers of Bosra were from Damascus, since then most shop owners are residents of the town. In the late Ottoman era and the French Mandate period, the agricultural relationship was between the small landowner and the sharecroppers, since agrarian reforms in the late 1950s and 1960s, the relevant relationship has been between the landowners and the wage laborers. Many of its residents have found work in the Persian Gulf states and Saudi Arabia, sending proceeds to their relatives in Bosra. Social changes together with increased access to education have largely diminished the traditional clan life according to historian Hanna Batatu.[11]

During the presidency of Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000), Bosra and the surrounding villages were left largely outside of government interference and, for the most part, were politically dominated by members of the prominent al-Miqdad clan who served as intermediaries of sorts between the residents of the town and the governor of Daraa and the Ba'ath Party branch secretary.[11]

On October 14, 2012, there was intense gunfire from government forces stationed at checkpoints on the main road running through the town.[citation needed] On 13 November 2012, fierce fighting was reported in the east side of the town.[citation needed] By January 2013, after 22 months of conflict amid the ongoing Syrian Civil War, some refugees fleeing Bosra spoke of ever-escalating violence with many bodies being left in the streets during the violence.[12] On 15 January 2013, it was reported that the citadel was used by the army to shell the town on a daily basis.[13] Since the beginning of February 2014 the city was under the control of the Syrian Army.[14] However, on 31 January 2015, the Army's 5th Division confronted a contingent from the rebels near the famous Roman Amphitheater – fierce firefights broke out between the groups.[15] On 1 February 2015, the Army forces shelled areas in the eastern neighborhood of the town.[16] On 25 March 2015, Syrian rebels seized the town, ousting Syrian soldiers and allied militiamen after four days of intense battle.[17]

Bosra was recaptured by the Syrian Arab Army on the 2 July 2018, following the surrender of the rebel forces. The recapture was a part of the ongoing Daraa Offensive, which has involved the surrender and/or reconciliation of many rebel groups in the area.

Ecclesiastical history

As capital of the late Roman province of Arabia Petraea, Bosra was its Metropolitan Archbishopric, under the jurisdiction of Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East.[18] Later it also became a Latin titular see. The Latin apostolic succession was ended, but the city was made eponymous of the Melkite Catholic Archeparchy of Bosra-Hauran, which has its actual Marian cathedral see in Khabab city.

Titular see

The Latin archdiocese was nominally restored as a Latin Metropolitan titular archbishopric in the 18th century.

It was vacant for decades, having had the following archiepiscopal incumbents (of the highest, Metropolitan, rank) :

- Giuseppe Maria Perrimezzi, Marists (O.M.) (1734.03.24 – 1740.02.17)

- Dominicus Arcaroli (1817.11.10 – 1826.06.25)

- Domenico Secondi, Conventual Franciscans (O.F.M. Conv.) (1841.07.15 – 1842.04.03)

- Francisco de Paul García Peláez (1843.01.27 – 1845.11.10)

- Waltar Steins Bisschop, S.J. (1867.01.11 – 1879.05.15)

- Vincenzo Taglialatela (1880.02.27 – 1897)

- Francisco Sáenz de Urturi y Crespo, Friars Minor (O.F.M.) (1899.04.27 – 1903)

- Martín García y Alcocer, O.F.M. (1904.07.30 – 1926.05.20)

- Peter Joseph Hurth, Holy Cross Fathers (C.S.C.) (1926.11.12 – 1935.07.31)

- Iwannis Gandour (1950.12.12 – 1961.07.16)

John Patrick Cody (1961.07.20 – 1964.11.08) as Coadjutor Archbishop of New Orleans (USA) (1961.07.20 – 1964.11.08), succeeded as Metropolitan Archbishop of New Orleans (USA) (1964.11.08 – 1965.06.14), transferred Metropolitan Archbishop of Chicago (USA) (1965.06.14 – death 1982.04.25), created Cardinal-Priest of S. Cecilia (1967.06.29 – 1982.04.25)- Iwannis Georges Stété (1968.08.20 – 1975.02.27)

Main sights

Ancient City of Bosra

Of the city which once counted 80,000 inhabitants, there remains today only a village settled among the ruins. The 2nd century Roman theater, constructed probably under Trajan, is the only monument of this type with its upper gallery in the form of a covered portico which has been integrally preserved. It was fortified between 481 and 1231.

Further, Nabatean and Roman monuments, Christian churches, mosques and Madrasahs are present within the half ruined enceinte of the city. The structure of this monument a central plan with eastern apses flanked by 2 sacristies exerted a decisive influence on the evolution of Christian architectural forms, and to a certain extent on Islamic style. Al-Omari Mosque of Bosra is one of the oldest surviving mosques in Islamic history.[19]

Close by are the Kharaba Bridge and the Gemarrin Bridge, both Roman bridges.

Climate

Bosra has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk). Rainfall is higher in winter than in summer. The average annual temperature in Bosra is 16.4 °C (61.5 °F). About 247 mm (9.72 in) of precipitation falls annually.

| Climate data for Bosra | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) | 13.5 (56.3) | 16.9 (62.4) | 21.9 (71.4) | 27.1 (80.8) | 30.7 (87.3) | 31.9 (89.4) | 32.3 (90.1) | 30.6 (87.1) | 26.7 (80.1) | 20.1 (68.2) | 13.9 (57.0) | 23.1 (73.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) | 3.1 (37.6) | 5.3 (41.5) | 8.5 (47.3) | 11.9 (53.4) | 14.6 (58.3) | 16.1 (61.0) | 16.3 (61.3) | 14.6 (58.3) | 11.8 (53.2) | 7.7 (45.9) | 3.5 (38.3) | 9.6 (49.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52 (2.0) | 53 (2.1) | 42 (1.7) | 15 (0.6) | 6 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (0.4) | 22 (0.9) | 47 (1.9) | 247 (9.7) |

| Source: climate-data.org | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In the late 1990s Bosra had an estimated population of 12,000.[3] Its population increased to 19,683 according to the 2004 census by the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics. The population of its metropolitan area was 33,839.[2]

Bosra's inhabitants are predominantly Sunni Muslims and are mostly divided between eight major clans. The leading clan is the al-Miqdad whose members immigrated to Bosra from al-Suwayda in the mid-18th-century. During this era they also dominated the nearby villages of Ghasm, Maaraba and Samaqiyat. However, the oldest clan of Bosra are the Hamd, a largely fair-skinned people, many members of which have blond hair and blue eyes. They claim to be descendants of the ancient Roman governor of Bosra, although other townspeople believe they are of Crusader origins. Regarding land ownership, the Hamd clan owns around 1,000 hectares in the town while the al-Miqdad clan owns roughly 12,000.[3] The latter's members were historically influential in the Hauran region and beyond, having had one of their own in the Ottoman parliament of Abd al-Hamid II in Constantinople during the Young Turks period and in the Syrian parliament during the French Mandate period. As of the late 1990s, members of the al-Miqdad clan occupied the positions of mayor, the chief imam of the main al-Omari Mosque, the chief of the town's bureau of antiquities as well as manager of Bosra's carpet workshop and the owner of the principal coffeehouse. While their members traditionally resided in the eastern quarter of old Bosra, they are currently prevalent throughout the town.[11]

Bosra also has a small Shia Muslim community of some fifty families. According to Palestinian American historian Hanna Batatu, the Shia inhabitants of Bosra were "relatively recent arrivals," and immigrated to the town from the city of Nabatieh in South Lebanon. Most of the working members of the Shia community are artisans or laborers.[3] Batatu also asserts that social changes in Bosra since Syrian independence have led to tribal diffusion, with intermarriage between the clans and between the Sunni and Shia communities having increased significantly.[11]

Notable people from Bosra

Shimon ben Lakish, 3rd century, amora of the second generation and rabbi

Titus of Bostra, fl. 4th century, Christian theologian- Saint Antipater of Bostra, fl. 5th century, Christian bishop

Bahira, c. 600, Assyrian monk

Ibn Kathir (1301–1373), Islamic scholar

Gallery

References

^ Günümüzde Suriye Türkmenleri. — Suriye’de Değişimin Ortaya Çıkardığı Toplum: Suriye Türkmenleri, p. 21 ORSAM Rapor № 83. ORSAM – Ortadoğu Türkmenleri Programı Rapor № 14. Ankara — November 2011, 33 pages.

^ ab General Census of Population and Housing 2004. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Daraa Governorate. (in Arabic)

^ abcd Batatu, 1999, p. 24

^ ab Beattie & Pepper, p. 126.

^ Meinecke, 1996, pp. 31-32.

^ abc Meinecke, 1996, p. 35

^ le Strange, 1890, p. 425

^ Meinecke, 1996, p. 37

^ Meinecke, 1996, pp. 38-39.

^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 219.

^ abcd Batatu, 1999, p. 25

^ Channel Four News, 31 January 2013

^ "سيف الحوراني الإفراج عن الحرائر الذين اختطفهم النظام". Syria Tomorrow. 15 January 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hassan, Doha (19 February 2014). "Syrian army prepares for an attack from its southern border". Al Akhbar.

^ Leith Fadel (31 January 2015). "Dara'a: Syrian Army Attempts to Counter Rebels at Battalion 82". Al Masdar News.

^ "9 people killed in the capital's explosion, and 3 fighters in Daraa". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 1 February 2015. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015.

^ "Syria rebels seize ancient town of Busra Sham". Middle East Online. 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

^ Eastern Orthodox Archdiocese of Bosra, Horan and Jabal al-Arab

^ Al-Omari Mosque Archived 2009-09-08 at the Wayback Machine Archnet Digital Library.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Batatu, H. (1999). Syria's Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691002541.

Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001). The Rough Guide to Syria. Rough Guides.

Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

Meinecke, M. (1996). Patterns of Stylistic Changes in Islamic Architecture: Local Traditions Versus Migrating Artists. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814754924.

Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

Josias Leslie Porter (1855), "From Kunawat to Busrah", Five years in Damascus: Including an Account of the History, Topography, and Antiquities of That City; with Travels and Researches in Palmyra, Lebanon, and the Hauran, London: J. Murray, OCLC 399684

"Bozrah", Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine, London: J. Murray, 1858, OCLC 2300777

"Bosra", Palestine and Syria, Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1876

"Busrah", Cook's Tourists' Handbook for Palestine and Syria, London: T. Cook & Son, 1876

"Bosra", Palestine and Syria, Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1898

Sources and external links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bosra. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia on Bosra

- Official website of Bosra city

- Extensive photo site about Bosra

- Photo Gallery of Bosra

- GCatholic Latin titular see

Map of the town, Google Maps- Bosra-map; 22M

- Eastern Orthodox Archdiocese of Bosra, Horan and Jabal al-Arab

- Brief History of the Archdiocese of Bosra-Hauran