Museum of Modern Art

| |

| Established | November 7, 1929 (1929-11-07) |

|---|---|

| Location | 11 West 53rd Street New York, N.Y. 10019 |

| Coordinates | 40°45′41″N 73°58′40″W / 40.761484°N 73.977664°W / 40.761484; -73.977664 |

| Type | Art museum |

| Visitors | 2.8 million (2016)[1] Ranked 13th globally (2013)[2] |

| Director | Glenn D. Lowry |

| Public transit access | Subway: Fifth Avenue/53rd Street ( Bus: M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, M7, M10, M20, M50, M104 |

| Website | www.moma.org |

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

MoMA plays a major role in developing and collecting modernist art, and is often identified as one of the largest and most influential museums of modern art in the world.[3] MoMA's collection offers an overview of modern and contemporary art, including works of architecture and design, drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, prints, illustrated books and artist's books, film, and electronic media.[4]

The MoMA Library includes approximately 300,000 books and exhibition catalogs, over 1,000 periodical titles, and over 40,000 files of ephemera about individual artists and groups.[5] The archives holds primary source material related to the history of modern and contemporary art.[6]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Heckscher and other buildings (1929–39)

1.2 53rd Street (1939–present)

1.2.1 1930s and 1940s

1.2.2 1958 fire

1.2.3 1960–1982

1.2.4 1983–2013

1.2.5 2014–2016

1.2.6 2017 and forward

2 Exhibition houses

3 Artworks

3.1 Selected collection highlights

3.2 Film

3.3 Library

3.4 Architecture and design

4 Management

4.1 Attendance

4.2 Admission

4.3 Finances

5 Key people

5.1 Officers and the board of trustees

5.1.1 Board of trustees

5.2 Directors

5.3 Chief curators

6 See also

7 References

7.1 Citations

7.2 Sources

8 External links

History

Heckscher and other buildings (1929–39)

The idea for the Museum of Modern Art was developed in 1929 primarily by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) and two of her friends, Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan.[7] They became known variously as "the Ladies", "the daring ladies" and "the adamantine ladies". They rented modest quarters for the new museum in the Heckscher Building at 730 Fifth Avenue (corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street) in Manhattan, and it opened to the public on November 7, 1929, nine days after the Wall Street Crash. Abby had invited A. Conger Goodyear, the former president of the board of trustees of the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, to become president of the new museum. Abby became treasurer. At the time, it was America's premier museum devoted exclusively to modern art, and the first of its kind in Manhattan to exhibit European modernism.[8] One of Abby's early recruits for the museum staff was the noted Japanese-American photographer Soichi Sunami (at that time best known for his portraits of modern dance pioneer Martha Graham), who served the museum as its official documentary photographer from 1930 until 1968.[9][10]

Goodyear enlisted Paul J. Sachs and Frank Crowninshield to join him as founding trustees. Sachs, the associate director and curator of prints and drawings at the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, was referred to in those days as a collector of curators. Goodyear asked him to recommend a director and Sachs suggested Alfred H. Barr, Jr., a promising young protege. Under Barr's guidance, the museum's holdings quickly expanded from an initial gift of eight prints and one drawing. Its first successful loan exhibition was in November 1929, displaying paintings by Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, and Seurat.[11]

First housed in six rooms of galleries and offices on the twelfth floor of Manhattan's Heckscher Building,[12] on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, the museum moved into three more temporary locations within the next ten years. Abby's husband was adamantly opposed to the museum (as well as to modern art itself) and refused to release funds for the venture, which had to be obtained from other sources and resulted in the frequent shifts of location. Nevertheless, he eventually donated the land for the current site of the museum, plus other gifts over time, and thus became in effect one of its greatest benefactors.[13]:376, 386

During that time it initiated many more exhibitions of noted artists, such as the lone Vincent van Gogh exhibition on November 4, 1935. Containing an unprecedented sixty-six oils and fifty drawings from the Netherlands, as well as poignant excerpts from the artist's letters, it was a major public success due to Barr's arrangement of the exhibit, and became "a precursor to the hold van Gogh has to this day on the contemporary imagination".[13]:376

53rd Street (1939–present)

1930s and 1940s

The museum also gained international prominence with the hugely successful and now famous Picasso retrospective of 1939–40, held in conjunction with the Art Institute of Chicago. In its range of presented works, it represented a significant reinterpretation of Picasso for future art scholars and historians. This was wholly masterminded by Barr, a Picasso enthusiast, and the exhibition lionized Picasso as the greatest artist of the time, setting the model for all the museum's retrospectives that were to follow.[14]Boy Leading a Horse was briefly contested over ownership with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[15] In 1941, MoMA hosted the ground-breaking exhibition, Indian Art of the United States (curated by Frederic Huntington Douglas and Rene d'Harnoncourt), that changed the way American Indian arts were viewed by the public and exhibited in art museums.

The entrance to The Museum of Modern Art

When Abby Rockefeller's son Nelson was selected by the board of trustees to become its flamboyant president in 1939, at the age of thirty, he became the prime instigator and funder of its publicity, acquisitions and subsequent expansion into new headquarters on 53rd Street. His brother, David Rockefeller, also joined the museum's board of trustees in 1948 and took over the presidency when Nelson was elected Governor of New York in 1958.

David subsequently employed the noted architect Philip Johnson to redesign the museum garden and name it in honor of his mother, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. He and the Rockefeller family in general have retained a close association with the museum throughout its history, with the Rockefeller Brothers Fund funding the institution since 1947. Both David Rockefeller, Jr. and Sharon Percy Rockefeller (wife of Senator Jay Rockefeller) currently sit on the board of trustees.

In 1937, MoMA had shifted to offices and basement galleries in the Time-Life Building in Rockefeller Center. Its permanent and current home, now renovated, designed in the International Style by the modernist architects Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone, opened to the public on May 10, 1939, attended by an illustrious company of 6,000 people, and with an opening address via radio from the White House by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[16]

1958 fire

On April 15, 1958, a fire on the second floor destroyed an 18 foot long Monet Water Lilies painting (the current Monet water lilies was acquired shortly after the fire as a replacement). The fire started when workmen installing air conditioning were smoking near paint cans, sawdust, and a canvas dropcloth. One worker was killed in the fire and several firefighters were treated for smoke inhalation. Most of the paintings on the floor had been moved for the construction although large paintings including the Monet were left. Art work on the 3rd and 4th floors were evacuated to the Whitney Museum of American Art, which abutted it on the 54th Street side. Among the paintings that were moved was A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, which had been on loan by the Art Institute of Chicago. Visitors and employees above the fire were evacuated to the roof and then jumped to the roof of an adjoining townhouse.[17]

1960–1982

In 1969, the MoMA was at the center of a controversy over its decision to withdraw funding from the iconic anti-war poster And babies. In 1969, the Art Workers Coalition (AWC), a group of New York City artists who opposed the Vietnam War, in collaboration with Museum of Modern Art members Arthur Drexler and Elizabeth Shaw,[18] created an iconic protest poster called And babies. The poster uses an image by photojournalist Ronald L. Haeberle and references the My Lai Massacre. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) had promised to fund and circulate the poster, but after seeing the 2 by 3 foot poster MoMA pulled financing for the project at the last minute.[19][20] MoMA's Board of Trustees included Nelson Rockefeller and William S. Paley (head of CBS), who reportedly "hit the ceiling" on seeing the proofs of the poster.[19] The poster was included shortly thereafter in MoMA's Information exhibition of July 2 to September 20, 1970, curated by Kynaston McShine.[21] Another controversy involved Pablo Picasso's painting Boy Leading a Horse (1905–06), donated to MoMA by William S. Paley in 1964. The status of the work as being sold under duress by its German Jewish owners in the 1930s was in dispute. The descendants of the original owners sued MoMA and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, which has another Picasso painting, Le Moulin de la Galette (1900),[22] once owned by the same family, for return of the works. Both museums reached a confidential settlement with the descendants before the case went to trial and retained their respective paintings.[23][24][25] Both museums had claimed from the outset to be the proper owners of these paintings, and that the claims were illegitimate. In a joint statement the two museums wrote: "we settled simply to avoid the costs of prolonged litigation, and to ensure the public continues to have access to these important paintings."[26]

In 2011, MoMA acquired a building constructed and occupied by the American Folk Art Museum on West 53rd Street, adjacent to the Museum. The building was a well-regarded structure designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects and was sold in connection with a financial restructuring of the Folk Art Museum.[27] When MoMA announced that it was going to demolish the building in connection with its expansion, there was outcry and considerable discussion about the issue, but the museum ultimately proceeded with its original plans.[28]

1983–2013

Stairs in the Museum of Modern Art

Cross-section of the Museum of Modern Art

In 1983 the Museum more than doubled its gallery and increased curatorial department by 30 percent, and added an auditorium, two restaurants and a bookstore in conjunction with the construction of the 56-story Museum Tower adjoining the museum.[29]

In 1997, the museum undertook a major renovation and expansion designed by Japanese architect Yoshio Taniguchi with Kohn Pedersen Fox. The project, including an increase in MoMA's endowment to cover operating expenses, cost $858 million in total. The project nearly doubled the space for MoMA's exhibitions and programs and features 630,000 square feet (59,000 m2) of space. The Peggy and David Rockefeller Building on the western portion of the site houses the main exhibition galleries, and The Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education and Research Building provides space for classrooms, auditoriums, teacher training workshops, and the museum's expanded Library and Archives. These two buildings frame the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden, which was enlarged from its original configuration.

The museum was closed for two years in connection with the renovation and moved its public-facing operations to a temporary facility called MoMA QNS in Long Island City, Queens. When MoMA reopened in 2004, the renovation was controversial. Some critics thought that Taniguchi's design was a fine example of contemporary architecture, while many others were displeased with aspects of the design, such as the flow of the space.[30][31][32] In 2005, the museum sold land that it owned west of its existing building to Hines, a Texas real estate developer, under an agreement that reserved space on the lower levels of the building Hines planned to construct there for a MoMA expansion.[33]

2014–2016

The Hines building, designed by Jean Nouvel and called 53W53 received construction approval in 2014 and is projected to be completed in 2019.[34] Around the time of Hine's construction approval, MoMA unveiled its expansion plans, which encompass space in 53W53, as well as construction on the former site of the American Folk Art Museum on 53rd Street.[35]

2017 and forward

The plan was developed by the architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler. The first phase of construction began in 2014, with completion anticipated in 2019. The project adds 50,000 square feet of new gallery space to the museum. The new galleries, together with renovations to existing spaces, increase public space in the building by 25% relative to MoMA's configuration when the Tanaguchi building was completed in 2004.[36] In connection with the renovation, MoMA shifted its approach to presenting its holdings, moving away from separating the collection by disciplines such as painting, design and works on paper toward an integrated chronological presentation that encompasses all areas of the collection.[36]

In June 2017, patrons and the public were welcomed into MOMA to see the completion of the first phase of the $450 million expansion to the museum. "Spread over three floors of the art mecca off Fifth Avenue are 15,000 square-feet (about 1,400 square-meters) of reconfigured galleries, a new, second gift shop, a redesigned cafe and espresso bar and, facing the sculpture garden, two lounges graced with black marble quarried in France."[37] The two new lounges include "The Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin Lounge" and "The Daniel and Jane Och Lounge".[37][38]

"Still under construction are 50,000 square-feet (about 4,600 square-meters) of new galleries opening in 2019, bringing MoMA's total art-filled space to 175,000 square-feet (about 16,000 square-meters) on six floors. The expansion will allow more of the museum's collection of nearly 200,000 works to be displayed."[37] When finished the museum expansion project will give 25% more space for visitors and patrons to enjoy a relaxing sit down in one of the two new lounges or even have a fully catered meal.[37]

Exhibition houses

The MoMA occasionally has sponsored and hosted temporary exhibition houses, which have reflected seminal ideas in architectural history.

- 1949: exhibition house by Marcel Breuer

- 1950: exhibition house by Gregory Ain[39]

- 1955: Japanese Exhibition House by Junzo Yoshimura, reinstalled in Philadelphia, PA in 1957–58 and known now as Shofuso Japanese House and Garden

- 2008: Prefabricated houses planned[40][41] by:

- Kieran Timberlake Architects

- Lawrence Sass

- Jeremy Edmiston and Douglas Gauthier

- Leo Kaufmann Architects

- Richard Horden

Artworks

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907

Claude Monet, Reflections of Clouds on the Water-Lily Pond, c.1920

Considered by many to have the best collection of modern Western masterpieces in the world, MoMA's holdings include more than 150,000 individual pieces in addition to approximately 22,000 films and 4 million film stills. (Access to the collection of film stills ended in 2002, and the collection is mothballed in a vault in Hamlin, Pennsylvania.[42]) The collection houses such important and familiar works as the following:

Francis Bacon, Painting (1946)

Umberto Boccioni, The City Rises

Paul Cézanne, The Bather

Marc Chagall, I and the Village

Giorgio de Chirico, The Song of Love

Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory

Max Ernst, Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale

Paul Gauguin, Te aa no areois (The Seed of the Areoi)

Albert Gleizes, Portrait of Igor Stravinsky, 1914

Jasper Johns, Flag

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair

Roy Lichtenstein, Drowning Girl

René Magritte, The Empire of Lights

Kazimir Malevich, White on White 1918

Henri Matisse, The Dance

Jean Metzinger, Landscape, 1912–14

Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie-Woogie

Claude Monet, Water Lilies triptych

Barnett Newman, Broken Obelisk

- Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis (Man, Heroic and Sublime)

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950

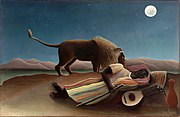

Henri Rousseau, The Dream, 1910- Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night

Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup Cans

Andrew Wyeth, Christina's World

Selected collection highlights

Paul Cézanne, The Bather, 1885–87

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Vincent van Gogh, The Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, 1889

Paul Gauguin, Te aa no areois (The Seed of the Areoi), 1892

Henri Rousseau, La Bohémienne endormie (The Sleeping Gypsy – Zingara che dorme), 1897

Henri Matisse, The Dance I, 1909

Henri Rousseau, The Dream, 1910

Henri Matisse, L'Atelier Rouge, 1911

Umberto Boccioni, 1913, Dynamism of a Soccer Player, 1913, oil on canvas, 193.2 × 201 cm

Henri Matisse, View of Notre-Dame, 1914

Giorgio De Chirico, Love Song, 1914

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918

It also holds works by a wide range of influential European and American artists including Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp, Walker Evans, Helen Frankenthaler, Alberto Giacometti, Arshile Gorky, Hans Hofmann, Edward Hopper, Paul Klee, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Dorothea Lange, Fernand Léger, Roy Lichtenstein, Morris Louis, René Magritte, Aristide Maillol, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Kenneth Noland, Georgia O'Keeffe, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, Auguste Rodin, Mark Rothko, David Smith, Frank Stella, and hundreds of others.

MoMA developed a world-renowned art photography collection first under Edward Steichen and then under Steichen's hand-picked successor John Szarkowski, which included photos by Todd Webb.[43] The department was founded by Beaumont Newhall in 1940.[44] Under Szarkowski, it focused on a more traditionally modernist approach to the medium, one that emphasized documentary images and orthodox darkroom techniques.

Film

In 1932, museum founder Alfred Barr stressed the importance of introducing "the only great art form peculiar to the twentieth century" to "the American public which should appreciate good films and support them". Museum Trustee and film producer John Hay Whitney became the first chairman of the Museum's Film Library from 1935 to 1951. The collection Whitney assembled with the help of film curator Iris Barry was so successful that in 1937 the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences commended the Museum with an award "for its significant work in collecting films ... and for the first time making available to the public the means of studying the historical and aesthetic development of the motion picture as one of the major arts".[45]

The first curator and founder of the Film Library was Iris Barry, a British film critic and author, whose three decades of pioneering work in collecting films and presenting them in coherent artistic and historical contexts gained recognition for the cinema as the major new art form of our century. Barry and her successors have built a collection comprising some eight thousand titles today, concentrating on assembling an outstanding collection of the important works of international film art, with emphasis being placed on obtaining the highest-quality materials.[46]

The exiled film scholar Siegfried Kracauer worked at the MoMA film archive on a psychological history of German film between 1941 and 1943. The result of his study, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947), traces the birth of Nazism from the cinema of the Weimar Republic and helped lay the foundation of modern film criticism.

Under the Museum of Modern Art Department of Film, the film collection includes more than 25,000 titles and ranks as one of the world's finest museum archives of international film art. The department owns prints of many familiar feature-length movies, including Citizen Kane and Vertigo, but its holdings also contains many less-traditional pieces, including Andy Warhol's eight-hour Empire, Fred Halsted's gay pornographic L.A. Plays Itself (screened before a capacity audience on April 23, 1974), various TV commercials, and Chris Cunningham's music video for Björk's All Is Full of Love.

Library

The MoMA library is located in Midtown Manhattan, with offsite storage in Long Island City, Queens. The non-circulating collection documents modern and contemporary art including painting, sculpture, prints, photography, film, performance, and architecture from 1880–present. The collection includes 300,000 books, 1,000 periodicals, and 40,000 files about artists and artistic groups. There are over 10,000 artist books in the collection.[47] The libraries are open by appointment to all researchers. The library's catalogue is called "Dadabase".[5] Dadabase includes records for all of the material in the library, including books, artist books, exhibition catalogue, special collections materials, and electronic resources.[5] The Museum of Modern Art's collection of artist books includes works by Ed Ruscha, Marcel Broodthaers, Susan Bee, Carl Andre, and David Horvitz.[48]

Additionally, the library has subscription electronic resources along with Dadabase. These include journal databases (such as JSTOR and Art Full Text), auction results indexes (ArtFact and Artnet), the ARTstor image database, and WorldCat union catalog.[49]

Architecture and design

MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design was founded in 1932[50] as the first museum department in the world dedicated to the intersection of architecture and design.[51] The department's first director was Philip Johnson who served as curator between 1932–34 and 1946–54.[52]

The collection consists of 28,000 works including architectural models, drawings and photographs.[50] One of the highlights of the collection is the Mies van der Rohe Archive.[51] It also includes works from such legendary architects and designers as Frank Lloyd Wright,[53][54][55][56]Paul László, the Eameses, Isamu Noguchi, and George Nelson. The design collection contains many industrial and manufactured pieces, ranging from a self-aligning ball bearing to an entire Bell 47D1 helicopter. In 2012, the department acquired a selection of 14 video games, the basis of an intended collection of 40 that is to range from Pac-Man (1980) to Minecraft (2011).[57]

Management

Attendance

MoMA has seen its average number of visitors rise from about 1.5 million a year to 2.5 million after its new granite and glass renovation. In 2009, the museum reported 119,000 members and 2.8 million visitors over the previous fiscal year. MoMA attracted its highest-ever number of visitors, 3.09 million, during its 2010 fiscal year;[58] however, attendance dropped 11 percent to 2.8 million in 2011.[59] Attendance in 2016 was 2.8 million, down from 3.1 million in 2015.[1]

The museum was open every day since its founding in 1929, until 1975, when it closed one day a week (originally Wednesdays) to reduce operating expenses. In 2012, it again opened every day, including Tuesday, the one day it has traditionally been closed.[60]

Admission

The Museum of Modern Art charges an admission fee of $25 per adult.[61] Upon MoMA's reopening, its admission cost increased from $12 to $20, making it one of the most expensive museums in the city. However, it has free entry on Fridays after 4:00 pm, as part of the Uniqlo Free Friday Nights program. Many New York area college students also receive free admission to the museum.[62]

Finances

A private non-profit organization, MoMA is the seventh-largest U.S. museum by budget;[63] its annual revenue is about $145 million (none of which is profit). In 2011, the museum reported net assets (basically, a total of all the resources it has on its books, except the value of the art) of just over $1 billion.

Unlike most museums, the museum eschews government funding, instead subsisting on a fragmented budget with a half-dozen different sources of income, none larger than a fifth.[64] Before the economic crisis of late 2008, the MoMA's board of trustees decided to sell its equities in order to move into an all-cash position. An $858 million capital campaign funded the 2002–04 expansion,[63] with David Rockefeller donating $77 million in cash. In 2005, Rockefeller pledged an additional $100 million toward the museum's endowment.[65] In 2011, Moody's Investors Service, a bond rating agency, rated $57 million worth of new debt in 2010 with a positive outlook and echoed their Aa2 bond credit rating for the underlying institution. The agency noted that MoMA has "superior financial flexibility with over $332 million of unrestricted financial resources", and has had solid attendance and record sales at its retail outlets around the city and online. Some of the challenges that Moody's noted were the reliance that the museum has on the tourist industry in New York for its operating revenue, and a large amount of debt. The museum at the time had a 2.4 debt-to-operating revenues ratio, but it was also noted that MoMA intended to retire $370 million worth of debt in the next few years. Standard & Poor's raised its long-term rating for the museum as it benefited from the fundraising of its trustees.[66] After construction expenses for the new galleries are covered, the Modern estimates that some $65 million will go to its $650 million endowment.

MoMA spent $32 million to acquire art for the fiscal year ending in June 2012.[67]

MoMA employs about 815 people.[64] The museum's tax filings from the past few years suggest a shift among the highest paid employees from curatorial staff to management.[68] The museum's director Glenn D. Lowry earned $1.6 million in 2009[69] and lives in a rent-free $6 million apartment above the museum.[70]

Key people

Officers and the board of trustees

Currently, the board of trustees includes 46 trustees and 15 life trustees. Even including the board's 14 "honorary" trustees, who do not have voting rights and do not play as direct a role in the museum, this amounts to an average individual contribution of more than $7 million.[68] The Founders Wall was created in 2004, when MoMA's expansion was completed, and features the names of actual founders in addition to those who gave significant gifts; about a half-dozen names have been added since 2004. For example, Ileana Sonnabend's name was added in 2012, even though she was only 15 when the museum was established in 1929.[71]

In Memoriam – David Rockefeller (1915–2017)

| Vice chairmen:

|

Board of trustees

Board of trustees:

|

|

|

|

Life trustees:

|

| Honorary trustees:

|

|

Directors

Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (1929–43)- No director (1943–9; the job was handled by the chairman of the museum's coordination committee and the director of the Curatorial Department)[72][73]

Rene d'Harnoncourt (1949–68)

Bates Lowry (1968–69)

John Brantley Hightower (1970–2)

Richard Oldenburg (1972–95)

Glenn D. Lowry (1995–present)

Chief curators

Klaus Biesenbach, director of MoMA PS1 and chief curator at large (2009–2018)

Barry Bergdoll, chief curator of architecture and design (2007–13)- Sabine Breitwieser, chief curator of media and performance art (2010–3)

- Christophe Cherix, chief curator of prints and illustrated books (2010–3), drawings and prints (2013–present)

- Stuart Comer, chief curator of media and performance art (2014–present)

Cornelia Butler, chief curator of drawings (2006–13)

Quentin Bajac, chief curator of photography (2012–2018)- Rajendra Roy, chief curator of film (2007–present)

- Martino Stierli, chief curator of architecture and design (2015–present)

Ann Temkin, chief curator of painting and sculpture (2008–present)

See also

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

- Rene d'Harnoncourt

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- Dorothy Canning Miller

- Sam Hunter

- John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- Talk to Me (exhibition)

The Family of Man exhibit (1955)- WikiProject MoMA

References

Citations

^ ab "Visitor figures 2016: Christo helps 1.2 million people to walk on water". theartnewspaper.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Top 100 Art Museum Attendance Archived April 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., The Art Newspaper, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

^ Kleiner, Fred S.; Christin J. Mamiya (2005). "The Development of Modernist Art: The Early 20th Century". Gardner's Art through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Thomson Wadsworth. p. 796. ISBN 0-495-00478-2. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016.The Museum of Modern Art in New York City is consistently identified as the institution most responsible for developing modernist art ... the most influential museum of modern art in the world.

^ Museum of Modern Art – New York Art World Archived February 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

^ abc "MoMA". Archived from the original on February 5, 2016.

^ "MoMA". Archived from the original on February 13, 2016.

^ "The Museum of Modern Art". The Art Story. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

^ First modern art museum featuring European works in Manhattan – Michael FitzGerald, Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995. p. 120.

^ "Seattle Camera Club from Kathy Muir". Retrieved December 31, 2014.

^ Smith, Roberta (September 11, 2015). "Review: Picasso, Completely Himself in 3 Dimensions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

^ Origins of MoMA and first successful loan exhibition – see John Ensor Harr and Peter J. Johnson, The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988. pp. 217–18.

^ Carter B. Horsley. "The Crown Building (formerly the Heckscher Building)". The City Review. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016.

^ ab Bernice Kert, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

^ MoMA's international prominence through the Picasso retrospective of 1939–40 – see FitzGerald, op. cit. (pp. 243–62)

^ Carol Vogel, "Two Museums Go to Court Over the Right to Picassos", The New York Times, December 8, 2007 Archived July 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Art: Beautiful Doings". TIME.com. May 22, 1939. Archived from the original on January 29, 2008.

^ the making of: movies, art, &c., by greg allen Archived January 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.. greg.org (September 2, 2010). Retrieved September 4, 2010.

^ M. Paul Holsinger, "And Babies" in War and American Popular Culture Archived May 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Greenwood Press, 1999, pg. 363

^ ab Francis Frascina. Art, politics, and dissent: aspects of the art left in sixties America Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., pp. 175–186+ discuss the creation of the poster.

^ Peter Howard Selz, Susan Landauer. Art of engagement: visual politics in California and beyond Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., pg. 46.

^ Kenneth R. Allan, "Understanding Information", ed. Michael Corris, Conceptual Art, Theory, Myth, and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 147–148.

^ Pablo Picasso, Le Moulin de la Galette (1900), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archived April 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Two Museums Go to Court Over the Right to Picassos". The New York Times. December 8, 2007. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017.

^ Judge Rebukes Museums for Secret Picasso Settlement, The New York Times Artsbeat blog, June 19, 2009, Archived July 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

^ Christine Kearney, "NY museums settle in claim of Nazi-looted Picassos" Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine., Reuters, February 2, 2009

^ Guggenheim Settles Litigation and Shares Key Findings Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine., www.guggenheim.org, March 25, 2009

^ Taylor, Kate (May 10, 2011). "MoMA to Buy Building Used by Museum of Folk Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

^ Pogrebin, Robin (April 1, 2014). "Architects Mourn Former Folk Art Museum Building". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017.

^ Museum of Modern Art Expansion Archived January 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.. Pcparch.com. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

^ Updike, John (November 15, 2004). "Invisible Cathedral". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2010.Nothing in the new building is obtrusive, nothing is cheap. It feels breathless with unspared expense. It has the enchantment of a bank after hours, of a honeycomb emptied of honey and flooded with a soft glow.

^ Smith, Roberta (November 1, 2006). "Tate Modern's Rightness Versus MoMA's Wrongs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2007.The museum's big, bleak, irrevocably formal lobby atrium ... is space that the Modern could ill afford to waste, and such frivolousness continues in its visitor amenities: the hard-to-find escalators and elevators, the too-narrow glass-sided bridges, the two-star restaurant on prime garden real estate where there should be an affordable cafeteria ...Yoshio Taniguchi's MoMA is a beautiful building that plainly doesn't work.

^ Rybczynski, Witold (March 30, 2005). "Street Cred: Another Way of Looking at the New MOMA". Slate.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

^ Vogel, Carol (2007). "MoMA Sells Land for $125 Million - Report". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

^ "53 West 53rd - The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

^ Pogrebin, Robin (January 8, 2014). "A Grand Redesign of MoMA Does Not Spare a Notable Neighbor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

^ ab Pogrebin, Robin (June 1, 2017). "MoMA's Makeover Rethinks the Presentation of Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

^ abcd The Associated Press (June 2, 2017). "MoMA expanding its Manhattan space, view of NYC outdoors". WTOP. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

^ Gannon, Devin (May 1, 2017). "MoMA reveals final design for $400M expansion". 6sqft. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

^ Denzer, Anthony (2008). Gregory Ain: The Modern Home as Social Commentary. Rizzoli Publications. ISBN 0-8478-3062-4. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008.

^ MoMA Announces Selection of Five Architects to Display Prefabricated Homes Outside Museum in Summer 2008

^ Pogrebin, Robin (January 8, 2008). "Is Prefab Fab? MoMA Plans a Show". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

^ William E. Jones, introduction to Cruising the Movies, South Pasadena, California, Semiotext(e), 2015,

ISBN 9781584351719, p. 31.

^ "Todd Webb, 94, Peripatetic Photographer". The New York Times. April 22, 2000. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

^ Smith, Roberta (October 12, 1991). "Peter Galassi Is Modern's Photo Director". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

^ "History of MoMA Film Collection". Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

^ The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, New York, 1997, p. 527

^ "MoMA". Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

^ "Arcade – New York Art Resources Consortium – Artists' Books".

^ "MoMA". Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

^ ab Broome, Beth: A Landmark Acquisition for MoMA’s Architecture and Design Department Archived September 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. in the Architectural Record, November 4, 2011

^ ab MoMA: Architecture and Design Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., retrieved November 30, 2011

^ MOMA: Philip Johnson Papers in The Museum of Modern Art Archives, 1995 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Frank Lloyd Wright Exhibition Set to Open at MoMA". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

^ Robert Sullivan. "— Vogue". Vogue. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

^ "Frank Lloyd Wright and the City: Density vs. Dispersal". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015.

^ "Frank Lloyd Wright". The Museum of Modern Art.

^ Antonelli, Paola (November 29, 2012). "Video Games: 14 in the Collection, for Starters". MoMA. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

^ Erica Orden (June 29, 2010), MoMA Attendance Hits Record High Archived July 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Wall Street Journal.

^ Philip Boroff (January 12, 2012), MoMA Visitors Fall, Met Museum’s Rise, Led by Blockbusters Archived January 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg.

^ Carol Vogel (September 25, 2012), MoMA Plans to Be Open Every Day Archived November 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

^ "Locations, hours, and admission". MoMA. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

^ "Discounts". The Museum of Modern Art. June 26, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

^ ab Philip Boroff (August 10, 2009), Museum of Modern Art’s Lowry Earned $1.32 Million in 2008–2009 Bloomberg.

^ ab Arianne Cohen (June 3, 2007), A Museum Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. New York Magazine.

^ Carol Vogel (April 13, 2005), MoMA to Receive Its Largest Cash Gift Archived September 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

^ Katya Kazakina (April 11, 2012), S&P Raises Museum of Modern Art’s Debt Rating on Management Archived January 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg.

^ Robin Pogrebin (July 22, 2013), [Qatar Uses Its Riches to Buy Art Treasures] The New York Times.

^ ab Hugh Eakin (November 7, 2004), MoMA's Funding: A Very Modern Art, Indeed Archived May 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

^ Philip Boroff (August 1, 2011), MoMA Raises Admission to $25, Paid Director Lowry $1.6 Million Archived January 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg.

^ Kevin Flynn and Stephanie Strom (August 9, 2010), "Plum Benefit to Cultural Post: Tax-Free Housing", The New York Times Archived April 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine..

^ Patricia Cohen (November 28, 2012), MoMA Gains Treasure That Met Also Coveted Archived November 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

^ "Promoted to Director Of Modern Art Museum". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014.

^ "A.H. Barr Jr. Retires at Modern Museum; Director Since 1929 to Devote His Full Time to Writing on Art". The New York Times. October 28, 1943. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

- Allan, Kenneth R. "Understanding Information", in Conceptual Art: Theory, Myth, and Practice. Ed. Michael Corris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. pp. 144–168.

Barr, Alfred H; Sandler, Irving; Newman, Amy (January 1, 1986). Defining modern art: selected writings of Alfred H. Barr, Jr. New York: Abrams. ISBN 0810907151.

- Bee, Harriet S. and Michelle Elligott. Art in Our Time. A Chronicle of the Museum of Modern Art, New York 2004,

ISBN 0-87070-001-4. - Fitzgerald, Michael C. Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995.

- Geiger, Stephan. The Art of Assemblage. The Museum of Modern Art, 1961. Die neue Realität der Kunst in den frühen sechziger Jahren, (Diss. University Bonn 2005), München 2008,

ISBN 978-3-88960-098-1. - Harr, John Ensor and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988.

- Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

- Lynes, Russell, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art, New York: Athenaeum, 1973.

- Reich, Cary. The Life of Nelson A. Rockefeller: Worlds to Conquer 1908–1958. New York: Doubleday, 1996.

- Rockefeller, David. Memoirs. New York: Random House, 2002.

- Schulze, Franz. Philip Johnson: Life and Work. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Staniszewski, Mary Anne. The Power of Display. A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art, MIT Press 1998,

ISBN 0-262-19402-3. - Wilson, Kristina. The Modern Eye: Stieglitz, MoMA, and the Art of the Exhibition, 1925–1934. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

- Glenn Lowry. The Museum of Modern Art in this Century. 2009 Paperback: 50 pages.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museum of Modern Art (New York City). |

- Official website

Jeffers, Wendy (November 2004). "Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Patron of the modern". Magazine Antiques. 166 (55): 118. 14873617. Retrieved January 28, 2016 – via EBSCOhost. (Subscription required (help)).

The New York Times, 2007: Donors Sweetened Director's Pay At MoMA, Prompting Questions Controversy over the compensation package of MoMA's Director, Glenn D. Lowry.- Taniguchi and the New MOMA

- Museum Conservation Lab Renovation

- MoMA Exhibition History List (1929–Present)

Coordinates: 40°45′41″N 73°58′40″W / 40.761484°N 73.977664°W / 40.761484; -73.977664