Sobibór extermination camp

| Sobibór | |

|---|---|

| Extermination camp | |

Sobibór extermination camp memorial, pyramid of sand mixed with human ashes  Location of Sobibór (right of centre) on the map of German extermination camps marked with black and white skulls. Poland's borders before the Second World War | |

Sobibór Location of Sobibór in Poland today | |

| Coordinates | 51°26′50″N 23°35′37″E / 51.44722°N 23.59361°E / 51.44722; 23.59361Coordinates: 51°26′50″N 23°35′37″E / 51.44722°N 23.59361°E / 51.44722; 23.59361 |

| Other names | SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor |

| Known for | Genocide during the Holocaust |

| Location | Near Sobibór, General Government (occupied Poland) |

| Built by |

|

| Commandant |

|

| Original use | Extermination camp |

| First built | March 1942 – May 1942 |

| Operational | 16 May 1942 – 14 October 1943[1] |

| Number of gas chambers | 3 (expanded to 6)[2] |

| Inmates | Jews mainly from Poland, but also from France, Germany, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union (including POWs) |

| Number of inmates | Est. 600–650 slave labour at any given time |

| Killed | Est. min. 200,000–250,000 |

| Notable inmates | Joseph Serchuk, Dov Freiberg, Alexander Pechersky |

Sobibór (or Sobibor /soʊˈbiːbɔːr/;[3]Polish: [sɔˈbʲibur]) was a Nazi German extermination camp built and operated by the SS during World War II near the railway station of Sobibór near Włodawa within the semi-colonial territory of General Government of the occupied Second Polish Republic.

The camp was part of the secretive Operation Reinhard, the deadliest phase of the Holocaust in German-occupied Poland. Its official German name was SS-Sonderkommando Sobibór.[4]Jews from Poland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union (including Jewish-Soviet POWs),[5][6][7] were transported to Sobibór by rail. Most were suffocated in gas chambers fed by the exhaust of a large petrol engine.[8]

At least 200,000 people were murdered at Sobibór[9]. At the postwar trial against the former SS personnel of Sobibór, held in Hagen two decades into the Cold War, Professor Wolfgang Scheffler estimated the number of murdered Jews to have been at least 250,000, while

Gasmeister ("Gas Master") Erich Bauer estimated 350,000. [10][11] This number would make it the fourth most deadly extermination camp, after Bełżec, Treblinka, and Auschwitz.

During the revolt of 14 October 1943, about 600 prisoners tried to escape. About half succeeded in crossing the fence, of whom around 50 eluded re-capture, including Selma Wijnberg and her future husband Chaim Engel. They later married and lived to testify against Nazi war criminals. Shortly after the revolt, the Germans closed the camp, bulldozed the earth, and planted it over with pine trees to conceal its location. Today, the site is occupied by the Sobibór Museum. It displays a pyramid of ashes and crushed bones of the victims collected from the cremation pits.

In September 2014, a team of archaeologists unearthed remains of the gas chambers under the asphalt road. Also discovered in 2014 were a pendant inscribed with the words "Land of Israel (Eretz Israel)", in Hebrew, English, and Arabic, dating from 1927; earrings; a wedding band bearing a Hebrew inscription; and perfume bottles that belonged to Jewish victims.[12][13]

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Camp construction

1.2 Layout

2 Killing process

3 Uprising

3.1 After the revolt

4 Operational structure

4.1 Camp guards

5 Chain of command

6 Death toll

7 Commemoration

8 Dramatisations and testimonies

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

12 External links

Background

Beginning in 1940, the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) had established the so-called Lublin Reservation near Sobibór. It comprised sixteen forced labour camps, built as part of the new Nisko und Lublin Plan of Jewish resettlement. The district was intended to become an agricultural centre of the General Plan East, to be inhabited by the ethnic German "colonists" brought by Heim ins Reich into the Empire. About 95,000 Jews, expelled from as far away as Warsaw and Vienna, were brought to the area in order to build latifundia in exchange for a small monthly pay.[14] Most prisoners were housed in a network of sub-camps set up in pre-existing structures such as converted school buildings, factories, and farms. The Krychów camp was the main branch of the new complex. It was set up at a former Polish correctional centre and was the largest of the forced labour camps of the Nisko Plan.[15] During preparations for the Wehrmacht attack on the Soviet positions in eastern Poland, the Plan was discontinued.[16] Soon after that, the concentration of Jews in the area was discussed by the Nazi officials at the October 1941 meeting in occupied Lublin, attended by Hans Frank, Ernst Boepple, and Odilo Globocnik among others, who proposed the creation of a new order.[17]

Sobibór extermination camp was built in March and April 1942 as soon as the Final Solution was set in motion at the Wannsee Conference.[18] By this time the Chełmno and Bełżec extermination camps were already operating. Beginning on 17 March 1942, Sobibór was used for mass extermination of Jews deported from the Lublin Ghetto.[19] The new camp's location, near the Sobibór railway station, was selected due to its proximity to the Chełm – Włodawa railway line connecting General Government with Reichskommissariat Ukraine.[20]

Camp construction

Sobibor was located near the rural county's major town of Włodawa (called Wolzek by the Germans), 85 km south of the provincial capital, Brest-on-the-Bug (Brześć nad Bugiem in Polish). Camp construction was supervised by SS-Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla, a civil engineer by profession, who built the Bełżec camp (only three hours away). He applied the lessons learned there to the design of Sobibor.[19]

Construction began under SS direction on 1 March 1942.[21]

The first workers summoned to build the railroad spur were local people from neighbouring villages and towns, but the camp was primarily built by a Sonderkommando of about eighty Jews from ghettos within the vicinity of the camp. A squad of Ukrainian Trawniki-Männer, trained at the Trawniki SS compound, guarded the prisoners. Upon completion of construction, all the Jews involved were killed.[22] In mid-April 1942, when the camp was nearly completed, several experimental gassings took place there.[23]Christian Wirth, the commander of Bełżec, and Inspector of Operation Reinhard arrived in Sobibór to witness one of the gassings, when thirty to forty Jewish women were brought from the Krychów camp for this purpose.[24] He reportedly complained about the fitting of the gas chambers doors.[23] Some 250 Jews from Krychów were killed during these trials.[20]

The first commandant of Sobibór, appointed by Heinrich Himmler, was SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl, the manager of the T-4 Euthanasia Program in Nazi Germany at both the Hartheim and Bernburg extermination hospitals. Stangl served as the Sobibór's commandant from 28 April to the end of August 1942.[2] According to Stangl, Odilo Globocnik initially stated that Sobibór was a supply camp for the army. Stangl learned the true nature of the camp only when Hermann Michel took him to see the gas chamber hidden in the woods: "The moment I saw it – I realised what Michel had had in mind – it looked exactly the same as the gas chamber in Schloss Hartheim."[23] Feeling overwhelmed by a new job, Stangl first studied the Bełżec camp operations and management, where the extermination operations had already started. He accelerated the completion of Sobibór.[25]

SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs, who spent time installing the killing apparatus at the three Reinhard death camps of Sobibór, Treblinka, and Bełżec, explained how the gassing of victims at Sobibór was developed. On Wirth's orders, he acquired a heavy gasoline engine in Lemberg, disassembled from an armoured vehicle or a tractor: a 200 horsepower, V-shaped, 8 cylinder, water-cooled motor, identical to the one at Bełżec. Fuchs installed the engine on a cement base at Sobibór in the presence of Floss, Bauer, Stangl, and Barbl, and connected the engine exhaust manifold to pipes leading to the gas chamber.[26]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

We put the engine on a concrete plinth and attached a pipe to the exhaust outlet. Then we tried out the engine. At first it did not work. I repaired the ignition and the valve and finally got the engine to start. The chemist whom I already knew from Bełżec went into the gas chamber with a measuring device in order to gauge the gas concentration. After that, a trial gassing was carried out. I seem to remember that thirty to forty women were gassed. The Jewesses had to undress in a clearing in the woods near the gas chamber. They were herded into the gas chamber by the above-mentioned SS members and Ukrainian volunteers. Once the women were locked inside, I attended to the engine together with Bauer. At first the engine was in neutral. We both stood next to the engine and switched it up to "release exhaust to chamber" so that the gases were channelled into the chamber. On the instigation of the chemist I revved up the engine to high RPM making further accelerating unnecessary. After about ten minutes the thirty to forty women were dead. The chemist and the SS gave the signal to turn off the engine. I packed up my tools and saw the bodies being taken away. A small Lorenbahn wagon on rails was used leading to an area farther away.

— Erich Fuchs[26]

Layout

Aerial photograph of the Sobibór perimeter, taken likely before 1942. Permanent structures are not there yet, including Camp II barracks (lower centre), Camp III, and Camp IV. The railway unloading platform (with visible prewar railway station) is marked with the red arrow; the location of gas chambers is marked with a cross. The undressing area, with adjacent "Road to Heaven" through the forest, is marked with a red square.

The camp was divided into three or four sections.[23] The administration and garrison area included the main entrance for road-bound traffic and living quarters for the staff. The second section included the railway platform, where the victims were sorted after disembarking from the Holocaust trains, as well as barracks where the Sonderkommando Jews performed camp labour. In the third section were the brick gas chambers with metal roofs and a small narrow-gauge rail. Workers pushed wagons by hand (the type used at sawmills), in order to trundle the gassed bodies from the chambers. Nearby were several mass graves.[23]

Unlike at Bełżec, at Sobibór the SS men lived within the camp's perimeter.[20] The Commander's lodge was located north of the guardhouse and close to the platform; the SS canteen, the living quarters for the SS staff, and an armoury, were next to it.[2] The Camp I prisoner barracks were built behind the garrison area, directly west of the main gate. The zone was made escape-proof by surrounding it with barbed wire fences and a moat constructed along the perimeter, outside of which were minefields.[27] The only opening was a gate leading to the work area. The camp zone included the living quarters for the Jewish prisoners as well as the prisoners' kitchen. Each labourer was given about 12 square feet (1.1 square metres) of sleeping space.[2]

The Camp II Vorlager was a larger section that included services for the killing process as well as the everyday operation of the camp. Some 400 Sonderkommando prisoners, including women, worked there. Lager II contained the warehouses used for storing the items taken from the victims, including clothes, food, hair, gold, and other valuables. This section also housed the main administration office. At Lager II the Jews were prepared for their death. Here they undressed, women's hair was shaved, clothing was searched and sorted, and documents were destroyed in the nearby furnace. The victims' final steps were taken on a path surrounded by barbed wire. It was called the "Road to Heaven", or der Schlauch(= "the hose"), and led directly to the gas chambers.[2]

At Camp III the victims were killed. It was in the northwestern part of the camp, where there were only two ways to enter the camp, from Lager II. The camp staff and personnel entered through a small plain gate. The entrance for the victims descended immediately into the gas chambers and was decorated with flowers and a Star of David above the entrance to the gas chambers.[2]

In the Sobibór gas chambers, 500 people were murdered at a time. Only recently, following an eight-year-long investigation, have Polish and Israeli researchers confirmed the exact location of the gas chambers at Sobibór. The discovery of the remains of the building's foundations, unearthed in 2014, was confirmed by Tomasz Kranz, the director of Poland's Majdanek State Museum at Lublin.[28] In May 2013, archaeologists conducting excavations near Camp III unearthed an escape tunnel, an open-air crematorium, human skeletal remains, as well as a substance that appeared to be blood, and the identification tag of a Jewish boy who was murdered at the camp.[29] Dr. Kranz also commented that "the whole former camp is one huge crime scene", with traceable evidence of the Holocaust present everywhere, although the SS leader, Heinrich Himmler, ordered the camp to be destroyed and the area planted with trees.[28]

Killing process

On either 16 or 18 May 1942, Sobibór became fully operational and began mass gassing operations. Trains entered the railway siding with the unloading platform, and the Jews on board were told they were in a transit camp. They were forced to hand over their valuables, separated by gender, and told to undress. The nude women and girls, recoiling in shame, were met by the Sonderkommando who chopped off their hair in a mere half a minute. Among the Friseur (barbers) were Thomas Blatt (age 15)[30] and Philip Bialowitz (age 13).[31] The condemned prisoners, formed into groups, were led along the 100-metre (330 ft) long "Road to Heaven" (Himmelstrasse) to the gas chambers, where they were killed using carbon monoxide released from the exhaust pipes of a tank engine.[8] During his trial, SS-Oberscharführer Kurt Bolender described the killing operations as follows.

Map of Sobibór. The "Road to Heaven": centre, vertical, with gas chambers at the end of it (top-right turn, horizontal slant). The burial, cremation and ash pits further right, at the edge of the woods

8 page from "Raczyński's Note" with Treblinka, Bełżec and Sobibór extermination camps - Part of official note of Polish government-in-exile to Anthony Eden 10 December 1942.

Before the Jews undressed, Oberscharführer Hermann Michel made a speech to them. On these occasions, he used to wear a white coat to give the impression he was a physician. Michel announced to the Jews that they would be sent to work. But before this they would have to take baths and undergo disinfection, so as to prevent the spread of diseases. After undressing, the Jews were taken through the "Tube", by an SS man leading the way, with five or six Ukrainians at the back hastening the Jews along. After the Jews entered the gas chambers, the Ukrainians closed the doors. The motor was switched on by the former Soviet soldier Emil Kostenko and by the German driver Erich Bauer from Berlin. After the gassing, the doors were opened, and the corpses were removed by a group of Jewish workers.

— Kurt Bolender[32]

Local Jews were delivered in absolute terror, amongst screaming and pounding. Foreign Jews, on the other hand were treated with deceitful politeness. Passengers from Westerbork, Netherlands had a comfortable journey. There were Jewish doctors and nurses attending them and no shortage of food or medical supplies on the train. Sobibór did not seem like a genuine threat.[33]

The non-Polish victims included 18-year-old Helga Deen from the Netherlands, whose diary was discovered in 2004; the writer Else Feldmann from Austria; Dutch Olympic gold medalist gymnasts Helena Nordheim, Ans Polak, and Jud Simons; gym coach Gerrit Kleerekoper; and magician Michel Velleman.[34] Selected female prisoners were sexually exploited at drunken orgies before being murdered. For instance, two women from Austria, who were film or theatre actresses, were gang raped by the SS-men before being shot. Gasmeister Erich Bauer testified about this:

I was blamed for being responsible for the death of the Jewish girls Ruth and Gisela, who lived in the so-called forester house. As it is known, these two girls lived in the forester house, and they were visited frequently by the SS men. Orgies were conducted there. They were attended by Bolender, Gomerski, Karl Ludwig, Franz Stangl, Gustav Wagner and Steubel. I lived in the room above them and due to these celebrations could not fall asleep after coming back from a journey.

— Erich Bauer [35]

After the killing in the gas chambers, the corpses were collected by Sonderkommando and taken to mass graves or cremated in the open air.[27] The burial pits were approx. 50-60m (160–200 ft) long, 10-15m (30–50 ft) wide, and 5-7m (15–20 ft) deep, with sloping sandy walls in order to facilitate the burying of corpses.[20]

Uprising

Rumours that the camp would be shut down started circulating among its inmates in spring of 1943, after a drop in the number of incoming prisoner transports. A secret note carried by the Sonderkommando prisoner from Bełżec, who had been transported to Sobibór only to be killed on the railway platform there, hinted at what would happen to the prisoners if the camp were dismantled. This then led Polish-Jewish prisoners to organise an underground committee aimed at escaping from the camp.[36] In September 1943, the Sobibór underground was unexpectedly reinforced by the addition of Soviet-Jewish POWs transported from the Minsk Ghetto (along with 2,000 victims of gassing).[37] Some who survived the selection[further explanation needed] joined the group and shared their military experience.[36]

Sobibór was the site of one of two successful uprisings by Jewish Sonderkommando prisoners during Operation Reinhard. The revolt at Treblinka extermination camp on 2 August 1943 resulted in up to 100 escapees. A similar revolt at Auschwitz-Birkenau on 7 October 1944 led to one of the crematoria being blown up, but nearly all the insurgents were killed.[38]

Sobibór Nazi German extermination camp insurgents with the Soviet NKVD officer, postwar photo

On 14 October 1943, under the cover of night, members of the Sobibór underground, led by Soviet-Jewish POW Alexander Pechersky from Minsk,[37] covertly killed 11 German SS officers, overpowered the camp guards, and seized the armory.[39] Although the plan was to kill all the SS and walk out of the main gate of the camp, the killings were discovered, and the inmates ran for their lives under fire. About 300 out of the 600 Sonderkommando prisoners in the camp escaped into the forests.[2] Most of them were recaptured by the search squads.[37]

Dutch historian and Sobibor survivor Jules Schelvis estimates that 158 inmates perished in the Sobibór revolt, killed by the guards or in the minefield surrounding the camp. A further 107 were murdered either by the SS, Wehrmacht, or Orpo police units pursuing the escapees. Some 53 insurgents died of other causes between the day of the revolt and 8 May 1945. There were 58 known survivors, 48 male and 10 female, from among the Arbeitshäftlinge prisoners performing slave-labour for the daily operation of Sobibór. Their time in the camp ranged from several weeks to almost two years. A handful of inmates managed to escape while assigned to the Waldkommando felling and preparing of trees for the body disposal pyres.[40]

After the revolt

Within days of the uprising, the SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the camp closed, dismantled, and planted with trees.[2] The gas chambers were demolished. Remnants of their foundations were covered with asphalt and made to look like a road.[41] The last prisoners still in the camp, who had been used to dismantle the buildings, were killed in late November, and the last guards left the site in December.[1] Four of the chambers were uncovered by archaeologists in 2014, using modern technology.[42]

Some Sobibór survivors were spared the gas chambers because they were transferred to slave-labour camps in the Lublin reservation, upon arriving at Sobibór. These people spent several hours at Sobibór and were transferred almost immediately to slave-labour projects including Majdanek and the Alter Flugplatz airfield in the city of Lublin, where materials looted from the gassed victims were prepared for shipment to Germany. Other forced labour camps included Krychów, Dorohucza, and Trawniki before the killing spree of Aktion Erntefest. Estimates for the number of people sent away from Sobibór range up to several thousand, of whom most perished before the end of the Nazi regime. The total number of people in this group include 16 known survivors (13 women and 3 men) from among the 34,313 Jews deported to Sobibór from the Netherlands.[40]

Operational structure

The chief commandant of Sobibór (April / August 1942), and later of Treblinka, was Hauptsturmführer Franz Stangl, who was responsible for overseeing the murders of at least 100,000 Jews from May 1942 to July 1942 at Sobibór, before his transfer.[43] He fled to Syria after Germany was defeated. Following problems with his employer taking too much interest in his adolescent daughter, Stangl moved with his family to Brazil in the 1950s. He worked in a Volkswagen car factory and was registered with the Austrian consulate under his own name. He was eventually caught, tried, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment. In 1971, he died in prison in Düsseldorf, a few hours after concluding a series of interviews with the British historian Gitta Sereny.[44][45]

The third-in-command at Sobibór, and the camp's Lager I zone commandant, was Oberscharführer Karl Frenzel. Over 20 years after the war ended, he was put on trial, convicted of war crimes in 1966, and sentenced to life. He was released after 16 years on appeal and because of his health.[44][46] Blatt interviewed him in 1983 and taped it. Present at the camp from its inception to its closure Frenzel (a hostile commentator) said the following about the prisoners killed at Sobibór: "Poles were not killed there. Gypsies were not killed there. Russians were not killed there... only Jews, Russian Jews, Polish Jews, Dutch Jews, French Jews."[47] Possibly due in part to Frenzel's testimony, followed by Blatt's inquiry, the Polish government from the Soviet era changed the memorial plaque at the site, which used to read: "Here the Nazis Killed 250,000 Russian Prisoners of War, Jews, Poles and Gypsies."[47] The new memorial plaque reads, "At This Site, Between the Years 1942 and 1943, There Existed a Nazi Death Camp Where 250,000 Jews and Approximately 1,000 Poles Were Murdered." The plaque also commemorates the revolt of 14 October 1943 and the escape of Jews from the camp.[48]

The SS executioner, "Gasmeister" Erich Bauer

Gustav Wagner, the deputy Sobibór commander, was on leave on the day of uprising (survivors such as Thomas Blatt say that the revolt would not have succeeded had he been present). Wagner was arrested in 1978 in Brazil. He was identified by Stanislaw Szmajzner, a Sobibór escapee, who greeted him with the words, "Hallo Gustl." Wagner replied that he remembered Szmajzner and that he had saved him and his three brothers. The court of first instance agreed to his extradition to Germany, but on appeal this extradition was overturned. In 1980, Wagner committed suicide, though the circumstances are controversial.[49][50]

Erich Bauer,[51] commander of Camp III and gas chamber executioner, explained the perpetrators' sense of teamwork in order to reach an atrocious result:

We were a band of "fellow conspirators" ("verschworener Haufen") in a foreign land, surrounded by Ukrainian volunteers whom we could not trust... The bond between us was so strong that Frenzel, Stangl and Wagner had had a ring with SS runes made from five-mark pieces for every member of the permanent staff. These rings were distributed to the camp staff as a sign so that the "conspirators" could be identified. In addition the tasks in the camp were shared. Each of us had at some point carried out every camp duty in Sobibór (station squad, undressing, and gassing).

— Erich Bauer, Gasmeister

I estimate that the number of Jews gassed at Sobibor was about 350,000. In the canteen at Sobibor I once overheard a conversation between Karl Frenzel, Franz Stangl and Gustav Wagner. They were discussing the number of victims in the extermination camps of Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor and expressed their regret that Sobibor "came last" in the competition.[51]

Camp guards

While the camp officers were both German and Austrian SS members, the camp guards under their command were Volksdeutsche from Reichskommissariat Ukraine as well as non-Jewish Soviet POWs, primarily from Ukraine.[52]

Before they were sent as guards to the concentration camps, most of the Soviet POWs underwent special training at Trawniki. This was originally a holding centre for Soviet POWs following Operation Barbarossa, whom the Sipo security police and the SD had designated either as potential collaborators or as dangerous persons.[53] The Stroop Report listed the Trawnikis Sonderdienst Guard Battalion as one assisting in the suppression of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.[54]

John Demjanjuk, a former Soviet POW, allegedly worked as a watchguard at Sobibór. He was temporarily convicted by a German lower court as an accessory to the murder of 28,060 Jews and sentenced to five years in prison on 12 May 2011.[55][56][57] He was released pending appeal and died in a German nursing home on 17 March 2012, aged 91, while awaiting the hearing. Because he died before the German Appellate Court could try his case, the German Munich District Court declared that Demjanjuk was "presumed innocent," that the previous interim conviction was invalidated and that he had no criminal record.[58][58][59]

Chain of command

| Name | Rank | Function and notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

Organisers of the camp (Germans and one former Austrian) | |||

Odilo Globočnik | SS-Brigadeführer | Major-General and SS Police Chief (SS-Polizeiführer) at the time, Head of Operation Reinhard | [2] [44] |

Hermann Höfle | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Captain, Coordinator of Operation Reinhard | [44] |

Richard Thomalla | SS-Obersturmführer | First Lieutenant, Head of death camp construction during Operation Reinhard | [2] [44] |

Erwin Lambert | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal, Head of gas chamber construction during Operation Reinhard | [44] |

Karl Steubl | SS-Sturmbannführer | Major, Commander of transportation units during Operation Reinhard | [44] [49] |

Christian Wirth | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Captain at the time, Inspector of Operation Reinhard | [44] |

Commandants (Germans and Austrians) | |||

Franz Stangl | SS-Obersturmführer | First Lieutenant, 28 April 1942 – 30 August 1942 transferred to Commandant of Treblinka extermination camp | [2] [44] [49] |

Franz Reichleitner | SS-Obersturmführer | First Lieutenant, 1 September 1942 – 17 October 1943;[2] promoted to Captain (Hauptsturmführer) after Himmler's visit on 12 February 1943 | [49] |

Deputy commandants (Germans and Austrians) | |||

Gustav Wagner | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, Deputy commandant (Quartermaster, sergeant major of the camp) | [2][44] [49] |

Johann Niemann | SS-Untersturmführer | Second Lieutenant, Deputy commandant, killed in the revolt | [44] [49] [20] |

Karl Frenzel | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, Commandant of Camp I (forced labor camp) | [2] [44] [49] |

Hermann Michel | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, Deputy commandant, gave speeches to trick condemned prisoners into entering gas chambers | [44] [49] [60] |

Gas chamber executioners (Germans) | |||

Erich Bauer | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, operated gas chambers | [2] [44] [49] |

Kurt Bolender | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, gas chambers' operator | [2] [44] [49] |

Other staff officers (Germans and Austrians) | |||

Heinrich Barbl | SS-Rottenführer | Private First Class, pipes for the gas chambers (from Action T4) | [49][61] |

Ernst Bauch | committed suicide in December 1942 on vacation in Berlin from his Sobibor duty | [49] | |

Rudolf Beckmann | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, killed in revolt | [49] [20] |

Gerhardt Börner | SS-Untersturmführer | Second Lieutenant | [51] |

Paul Bredow | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal, managed the "Lazarett" killing station | [2] [49] |

Max Bree | killed in the revolt | [49] | |

Arthur Dachsel | police sergeant, transferred from Belzec in 1942, burning of corpses (Sonnenstein) | [44] [49] | |

Werner Karl Dubois | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant | [2] [44] [49] |

Herbert Floss | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant | [2] [49] |

Erich Fuchs | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant | [2] [49] [51] |

Friedrich Gaulstich | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, killed in the revolt | [49] [20] |

Anton Getzinger | [49] | ||

Hubert Gomerski | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal | [44] [49] |

Siegfried Graetschus | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, Head of Ukrainian Guard (2/2), killed in the revolt | [2] [44] [49] |

Ferdinand "Ferdl" Grömer | Austrian cook, helped also with gassings | [49] | |

Paul Johannes Groth | supervised sorting of clothes in Lager II | [44] | |

Lorenz Hackenholt | SS-Hauptscharführer | First Sergeant | |

Josef Hirtreiter | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, transferred from Treblinka in October 1943 for a short while | [2] |

Franz Hödl | [44] [49] | ||

Jakob Alfred Ittner | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant | [44] [49] |

Robert Jührs | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal | [44] |

Aleks Kaizer | [44] | ||

Rudolf "Rudi" Kamm | [49] | ||

Johann Klier | SS-Untersturmführer | Second Lieutenant | [44] [49] [20] |

Fritz Konrad | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, killed in the revolt | [49] [20] |

Erich Lachmann | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, Head of Ukrainian Guard (1/2) | [44] [49] |

Karl Emil Ludwig | [44] [49] | ||

Willi Mentz | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal, transferred from Treblinka for a short time in December 1943 | [44] |

Adolf Müller | [49] | ||

Walter Anton Nowak | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, killed in the revolt | [2] [44] [49] |

Wenzel Fritz Rehwald | [44] [49] | ||

Karl Richter | [49] | ||

Paul Rost | SS-Untersturmführer | Second Lieutenant | [2] |

Walter "Ryba" (real name: Hochberg) | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal, killed in the revolt | [49] [20] |

Klaus Schreiber | [20] | ||

Hans-Heinz Friedrich Karl Schütt | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant | [2] [44] [49] |

Thomas Steffl | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, killed in the revolt | [49] [20] |

Ernst Stengelin | killed in revolt | [49] | |

Heinrich Unverhau | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal | [44] [49] |

Josef Vallaster | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, killed in the revolt | [49] [20] |

Otto Weiss | commandant of the Bahnhof-kommando at Lager I before Frenzel | [49] | |

Wilhelm "Willie" Wendland | [44] [49] | ||

Franz Wolf | SS-Oberscharführer | Staff Sergeant, brother of Josef Wolf (below) | [2] [44] [49] |

Josef Wolf | SS-Scharführer | Sergeant, killed in the revolt | [49] [20] |

Ernst Zierke | SS-Unterscharführer | Corporal | [44] |

Wachmänner guards (Ukrainians and Russians) | |||

Sobibór "Road to Heaven" in 2007

Russian

Ukrainian

| |||

Timeline of Sobibór, March 1942 – October 1943 | |

|---|---|

| March 1942 | Under the supervision of Richard Thomalla, SS and police authorities construct Sobibór extermination camp in the spring of 1942 in an isolated area not far from the local Chelm-Wlodawa rail line.[19] |

| April 1942 | The first test subjects for the gas chambers at Sobibór: The SS deports 2,400 Jews from Rejowiec, Lublin Voivodeship in early April 1942, the first deportation to Sobibór, and murders almost all of them upon arrival.[19] |

| 28 April 1942 | Franz Stangl arrives in Sobibór to take up the position of camp commandant. Stangl had been the deputy supervisor of the "euthanasia" institution at Hartheim, near Linz, Austria. As the purpose of the "euthanasia" operation was to murder institutionalised persons with physical and mental disabilities in gas chambers at facilities like Hartheim, Stangl was familiar with using carbon monoxide gas for killing large numbers of people.[19] |

| 3 May 1942 | Regular transports to Sobibór begin. The first transport consists of 200 Jews from Zamość. The camp staff conducts gassing operations in three gas chambers located in one brick building. Some 400 prisoners are selected to survive, temporarily, to supply manual labour necessary to support the mass murder function of the killing centre. During this first phase of deportations, from early May until the end of July 1942, the Sobibór killing centre authorities kill at least 61,400 Jews. Many of them were deported from cities and towns in the north and east of Lublin District; the majority were Jews deported from the German Reich, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia either directly or via the transit camp-ghetto in Izbica.[19] |

| July/August 1942 | The SS halts deportations to Sobibór in order to modernise the railway spur into the camp.[19] |

| 8 October 1942 | Camp authorities resume mass murder operations in the gas chambers of Sobibór with the arrival of more than 24,000 Slovak Jews between 8 and 20 October from the transit camp-ghetto Izbica in the Lublin District of the General Government. The camp authorities kill virtually all of the deportees upon arrival in reconstructed and newly added gas chambers, completed during the two-month lull in transports to Sobibór. The improvements in capacity enable the camp authorities to kill up to 1,300 people at a time. Newly constructed as well was a narrow railway trolley from the reception platform to the burial pits in order to facilitate the transfer of the sick, the dead and those unable to walk directly to the open ovens. Those still alive after this journey are shot by the SS staff or the Trawniki-trained guards.[19] |

| 12 February 1943 | Heinrich Himmler visits Sobibór to inspect operations. Several SS officers at the camp are promoted as a result. |

| 5 March 1943 | Deportations from the Netherlands. German SS and Police authorities begin deportations of Dutch Jews from transit camp Westerbork to Sobibór. In 19 transports from this date until July 1943, SS authorities in Westerbork deport over 34,000 Jews to Sobibór. Camp staff and guards kill almost all of them in the gas chambers or by shooting on arrival in the camp.[19] |

| April 1943 | Deportations from France. Two transports containing a total of 2,000 Jews from France arrive at Sobibór from the police transit camp Drancy, outside Paris. Deportations from France to camps in the east, primarily Auschwitz, began in March 1942 and continue until August 1944.[19] |

| July/October 1943 | Deportations from the Soviet Union. Following Himmler's order of July 1943 to liquidate the ghettos in Reichskommissariat Ostland, SS and police units liquidate ghettos in Minsk, Lida and Wilno (Vilnius, Vilne) and deport those who survived to Sobibór. The first transports from Minsk and Lida leave for Sobibór on 18 September. Included in the first deportation from Minsk (arrived 22 September) is Alexander "Sasha" Pechersky, a Soviet-Jewish prisoner of war, who, because of his military training, came to play a central role in the resistance movement in Sobibór. In September 1943 alone, SS and police authorities transported at least 13,700 Jews from ghettos in the occupied Soviet Union to Sobibór. The camp authorities gas or shoot most of them upon arrival.[19] |

| 14 October 1943 | Sobibór revolt. Prisoners carry out a revolt in Sobibór, killing close to a dozen German staff and Trawniki-trained guards. Of 600 prisoners left in Sobibór on this day, roughly 300 escape during the uprising.[2] Among the survivors is Alexander Pechersky, the Soviet prisoner-of-war who played a key role in planning the revolt. Of those who escape, the SS and police personnel from Lublin district recapture and shoot some 140. Some of the prisoners selected for temporary survival in Sobibór organised an underground resistance organisation in early summer of 1943 as it became apparent that gassing operations at Sobibór were slowing. Once the gassing operations were finished, the SS planned to dismantle the killing centre and reconfigure the facility first as a holding pen for women and children deported from villages in Belarus, which had been destroyed in the course of so-called anti-partisan operations, and, later, as an ammunition depot. Though no further prisoners arrived after the killing centre was remodelled, the facility was guarded by a small Trawniki-trained detachment until at least the end of March 1944. During the year and a half in which the Sobibór killing centre operated, camp authorities and the Trawniki-trained guards murdered at least 167,000 people. Virtually all of the victims were Jews.[19] |

| 17 October 1943 | Heinrich Himmler orders that Sobibór be closed and all evidence of the camp's existence be removed.[2] |

Death toll

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum states that at least 167,000 people were murdered at Sobibór. Other estimates range from 200,000 (Raul Hilberg) to 250,000 (Dr. Aharon Weiss, and Czesław Madajczyk).[65] The Dutch Sobibor Foundation lists a total of 170,165 people based on the arrival schedule cited in the Höfle Telegram as the source. For practical reasons it is not possible to list all the people murdered at the camp. The Nazi regime not only robbed Jews of their earthly possessions and their lives but attempted to eradicate all traces of their existence.[19][66]

I estimate that the number of Jews gassed at Sobibor was about 350,000. In the canteen at Sobibor I once overheard a conversation between Karl Frenzel, Franz Stangl and Gustav Wagner. They were discussing the number of victims in the extermination camps of Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor and expressed their regret that Sobibor "came last" in the competition.

— Erich Bauer, Gasmeister [51]

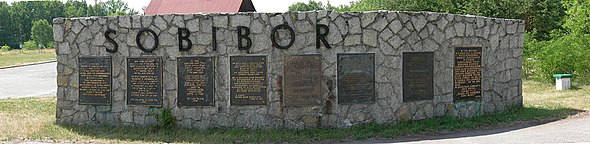

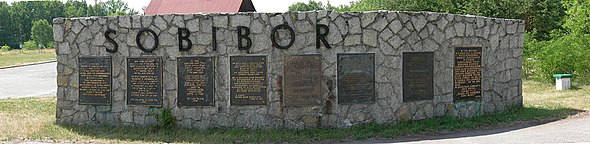

Commemoration

The first monument to Sobibór victims was erected on the historic site in 1965.[67] The Włodawa Museum, which was responsible for the monument, established a separate Sobibór branch on 14 October 1993, on the 50th anniversary of the armed uprising of Jewish prisoners there.[68] Following the celebrations of the 60th anniversary of the revolt in 2003, the grounds of the former death camp received a grant largely funded by the Dutch government to improve the exhibits. New walkways were introduced with signs indicating points of interest, but close to the burial pits, bone fragments still litter the area.[2] In the forest outside the camp is a statue honoring the fighters of Sobibór.[2]

Memorial at Sobibór Museum entrance

Sobibór railway yard

Memorial inside the camp

Dramatisations and testimonies

The mechanics of Sobibor death camp were the subject of interviews filmed on location for the 1985 documentary film Shoah by Claude Lanzmann. In 2001, due to Lanzmann's belief in the importance of the additional footage regarding Sobibor, as stated in the film's introduction, Lanzmann utilized unused interviews shot during the making of Shoah (along with new footage) to tell the story of the revolt and escape in his followup documentary Sobibor, 14 Octobre 1943, 16 Heures (Sobibor, 14 October 1943, 4 p.m.).[69]

In the 1978 American TV miniseries Holocaust broadcast in four parts, one of the principal characters, Rudi Weiss, a German Jew, is captured by the Nazis during a partisan attack upon a German convoy. Knocked unconscious, he wakes up in Sobibór, where he meets the Russian prisoners of war. The Sonderkommando are initially suspicious of him as a possible German spy planted within their midst, but he wins their trust and becomes part of the group that kills German SS officers as part of the uprising. Weiss and his new POW comrades successfully escape Sobibór during the mass break-out. The revolt was dramatised in the 1987 British TV film Escape from Sobibor, directed by Jack Gold and in the 2018 Russian movie "Sobibor", directed by Konstantin Khabensky.

One of the survivors, Regina Zielinski, has recorded her memories of the camp, and the escape in a conversation with Phillip Adams together with Elliot Perlman, in 2013 broadcast of Late Night Live by ABC.[70]

See also

- Sobibór trial

- Extermination camp death toll

Notes

^ ab Arad 1987, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, pp. 373-374. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0253342937.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacad Lest we forget (14 March 2004), ""Extermination camp Sobibor"". Archived from the original on 7 March 2005. Retrieved 7 March 2005.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

The Holocaust. Retrieved on 17 May 2013.

^ CMU Pronouncing Dictionary

^ William L. Shirer (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (3 ed., 1960). Simon and Schuster. p. 968. ISBN 0671728687. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

^ Philip "Fiszel" Bialowitz, Joseph Bialowitz, A Promise at Sobibór: A Jewish Boy’s Story of Revolt and Survival in Nazi-Occupied Poland, University of Wisconsin Press, 2010 .105

^ Thomas Toivi Blatt, From the Ashes of Sobibor: A Story of Survival, Northwestern University Press, 1997 p.131.

^ Alan J. Levine,Captivity, Flight, and Survival in World War II, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000 p.205.

^ ab Schelvis 2007, p. 100: Testimony of SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs about his own installation of the (at least) 200 HP, V-shaped, 8 cylinder, water-cooled petrol engine at Sobibor.

^ Raul Hilberg. The Destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press, 1985, p. 1219.

ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9

^ Schelvis 2014, p. 252.

^ Peter Hayes, Dagmar Herzog (2006). Lessons and Legacies VII: The Holocaust in International Perspective. Northwestern University Press. p. 272. Retrieved 11 October 2014.Between May 1942 and October 1943 some 200,000 to 250,000 Jews were killed at Sobibor according to the recently published Holocaust Encyclopedia edited by Judith Tydor Baumel.

^ Ofer Aderet (19 September 2014). "Archaeologists make more historic finds at site of Sobibor gas chambers". Haaretz.com.

^ Pempel, Kacper (18 September 2014). "Archaeologists uncover buried gas chambers at Sobibor death camp". U.S. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

^ Robert Rozett, Shmuel Spector. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 1135969507.

^ Sławomir Sobolewski. "Obozy pracy na terenie Gminy Hańsk" [World War II forced labour camps in Gmina Hańsk]. Hansk.info, the official webpage of Gmina Hańsk. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

^ Barbara Schwindt (2005). Das Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslager Majdanek: Funktionswandel im Kontext der "Endlösung". Königshausen & Neumann. pp. 52–54. ISBN 3-8260-3123-7. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

^ Bogdan Musial. "The Decision-Making Process for the Mass Murder of the Jews in the Generalgouvernement" (PDF). The Origins of "Operation Reinhard". Shoah Resource Center: 3–5. Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. XXVIII, Jerusalem 2000, pp. 113–153. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

^ Aktion Reinhard Camps. Sobibor Labour Camps. 15 June 2006. ARC Website.

^ abcdefghijklm USHMM (2015). "Sobibor: Chronology". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvw Chris Webb, Carmelo Lisciotto, Victor Smart (2009). "Sobibor Death Camp". HolocaustResearchProject.org. Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Holocaust Chronology: 1942". Encyclopedia Judaica. vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 348–349.

^ Arad 1987, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, pp. 30–31.

ISBN 0253342937.

^ abcde Mgr. Wojciech Mazurek (15 April – 15 June 2011). Summary of the Archaeological Research Program at the Former German Extermination Camp in Sobibór (PDF). Archaeological Research. Sobibór Museum: "Sub Terra" Badania Archeologiczne. pp. 11–12, 15–16. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

^ Arad 1987, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: the Operation Reinhard Death Camps, p. 184.

ISBN 0253342937.

^ Christian Zentner, Friedemann Bedürftig. The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, p. 878. Macmillan, New York, 1991.

ISBN 0-02-897502-2

^ ab Klee, Ernst & Dressen, Willi & Riess, Volker (1991). The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders p. 231. Konecky & Konecky,

ISBN 1-56852-133-2. Also in: Jules Schelvis (2014), Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp pp. 100–101. Bloomsbury Publishing,

ISBN 1472589068.

^ ab Matt Lebovic "70 years after revolt, Sobibor secrets are yet to be unearthed", Times of Israel 14 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

^ ab Justin Huggler, Berlin (18 September 2014). "Gas chambers discovered at Nazi death camp Sobibor". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

^ Aderet, Ofer (7 June 2013). "Archaeologists find escape tunnel at Sobibor death camp". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

^ Schelvis (2014) [2007]. Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. pp. 71–72. ISBN 1472589068.

^ Bialowitz, Philip. Life in Sobibór. A Promise at Sobibór: A Jewish Boy's Story of Revolt and Survival in Nazi-Occupied Poland. p. 79. ISBN 0299248038.

^ Arad 1987, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, p. 76.

ISBN 0253342937.

^ "Sobibor". The Holocaust Explained. Jewish Cultural Centre, London. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015 – via Internet Archive.As part of the concealment of the camp's purpose, some Dutch Jews dislodging at the ramp were ordered to write "calming letters" to their relatives in the Netherlands, with made-up details about the welcome and living conditions. Immediately after that, they were taken to the gas chambers.

CS1 maint: Unfit url (link)

^ "Michel Velleman (Sobibór, 2 juli 1943)". Digitaal Monument Joodse Gemeenschap in Nederland. Joods Monument. 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

^ Arad 1987, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, pp. 116–117.

ISBN 0253342937.

^ ab "Preparation – Sobibor Interviews". NIOD. 2009.

^ abc Schelvis, Jules (2007). Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Berg, Oxford & New Cork. pp. 147–168. ISBN 978-1-84520-419-8. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

^ Arad 1987, pp. 219–275.

^ Arad 1987, pp. 362–363.

^ ab Schelvis, Jules (2004). Vernietigingskamp Sobibor. De Bataafsche Leeuw. ISBN 9789067076296. Uitgeverij Van Soeren & Co (booksellers).

^ Reuters, Archaeologists Uncover Buried Gas Chambers At Sobibor Death Camp. The Huffington Post, 18 September 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

^ Terrence McCoy (19 September 2014), Archaeologists unearth hidden death chambers used to kill a quarter-million Jews at notorious camp. Washington Post. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

^ J.V.L. (2015). "Sobibor Extermination Camp: History & Overview". The Forgotten Camps. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamanaoap Sobibor − The Forgotten Revolt (Internet Archive). Webpage featuring first-person account of Holocaust survivor and Sonderkommando prisoner age 16, Thomas Blatt.

^ "SOME SIGNIFICANT CASE – Franz Stangl". Simon Wiesenthal Archiv. Simon Wiesenthal Center. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

^ "The Sobibor Trial – The Station Master at Treblinka www.HolocaustResearchProject.org". holocaustresearchproject.org.

^ ab Frenzel interview, Sobibor: The Forgotten Revolt website (Internet Archive).

^ Photo of new plaque at camp site, "More Documents," Sobibor: The Forgotten Revolt (Internet Archive).

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamanaoapaqaras Jules Schelvis & Dunya Breur. "Biographies of SS-men – Sobibor Interviews". Sobiborinterviews.nl. NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.The core of this website consists of thirteen interviews with survivors of the uprising on 14 October 1943 in the Sobibor extermination camp, originally recorded in 1983 and 1984 forty years after the fact.

^ Arad 1987, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: the Operation Reinhard death camps, p. 192.

ISBN 0253213053.

^ abcde Klee, Ernst, Dressen, Willi, Riess, Volker The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders.

ISBN 1-56852-133-2.

^ Sobibor: The Forgotten Revolt by Thomas (Toivi) Blatt HEP Issaquah 1998.

^ "Trawniki". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

^ Mgr Stanisław Jabłoński (1927–2002). "Hitlerowski obóz w Trawnikach". The camp history (in Polish). Trawniki official website. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

^ Matussek, Karin (12 May 2011). "Demjanjuk Convicted of Helping Nazis to Murder Jews During the Holocaust". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

^ "John Demjanjuk zu fünf Jahren Haft verurteilt". Die Welt. 12 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

^ "John Demjanjuk guilty of Nazi death camp murders". BBC News. 12 May 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

^ abc "Convicted Nazi criminal Demjanjuk deemed innocent in Germany over technicality". Haaretz.com. 23 March 2012.

^ "Nazi camp guard dead". The Age. Melbourne. 19 March 2012.

^ Nizkor Web Site Retrieved on 9 April 2009

^ Robin O'Neil (2009). "6". Belzec: Stepping Stone to Genocide. JewishGen.org. ISBN 0976475936.

^ "Survivors of the revolt – Sobibor Interviews". sobiborinterviews.nl.

^ "Interrogation of Mikhail Affanaseivitch Razgonayev Sobibor Death Camp Wachman - www.HolocaustResearchProject.org". holocaustresearchproject.org.

^ BBC News (12 May 2011). "John Demjanjuk guilty of Nazi death camp murders". Retrieved 12 May 2011.

^ Piotr Eberhardt, Jan Owsinski (2015). Estimated Numbers of Victims of the Nazi Extermination Camps. Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth Century Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 1317470966. Retrieved 19 September 2015.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ History of Sobibor at the Dutch Sobibor Foundation, Amsterdam.

^ E.S.R. (2013). "Museum of the Former Sobibór Death Camp". Information Portal to European Sites of Remembrance. Gedenkstattenportal zu Orten der Erinnerung in Europa. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

^ Virtual Shtetl (2013). "A discovery in the former Sobibór death camp". The extermination camp in Sobibór. Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

^ Sobibor, 14 Octobre 1943, 16 Heures. (2001). [DVD] Directed by C. Lanzmann. France: France 2 Cinéma; Les Films Aleph; Why Not Productions.

^ Regina Zielinski with Phillip Adams 'Escape from the Sobibor WW2 death camp,' Late Night Live Interview 29 October 2013

References

Krzysztof Bielawski (pl) (2010), Obóz zagłady w Sobiborze [Death camp in Sobibor] (in Polish), Warsaw: Virtual Shtetl, Museum of the History of Polish Jews, 1 of 3, retrieved 16 June 2016CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

Jakub Chmielewski (2014), Obóz zagłady w Sobiborze [Death camp in Sobibor] (in Polish), Lublin: Ośrodek Brama Grodzka, Pamięć Miejsca, retrieved 25 September 2014

Sobibor Museum (2014) [2006], Historia obozu [Camp history], Dr. Krzysztof Skwirowski, Majdanek State Museum, Branch in Sobibór (Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku, Oddział: Muzeum Byłego Obozu Zagłady w Sobiborze), archived from the original on 7 May 2013, retrieved 25 September 2014

Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253213053. Amazon Kindle, also in: Google Books, Snippet view, digitized from U. of Michigan, 2008.

Bialowitz, Philip; Bialowitz, Joseph (2010). A Promise at Sobibor: A Jewish Boy's Story of Revolt and Survival in Nazi Occupied Poland. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-24800-0. With Foreword by Władysław Bartoszewski.

Blatt, Thomas (1997). From the Ashes of Sobibor. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810113023 – via Google Books preview.

- Freiberg, Dov (2007), To Survive Sobibor, Gefen Publishing House.

ISBN 978-965-229-388-6

- Lev, Michael (2007), Sobibor, Gefen Publishing House.

ISBN 978-965-229-408-1

Novitch, Miriam (1980). Sobibor, Martyrdom and Revolt: Documents and Testimonies. ISBN 0-89604-016-X.

Schelvis, Jules (2014) [2007]. Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Translated by Dixon, Karin. Berg Publishers (2007), Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014. ISBN 1472589068 – via Google Books, preview.

Sereny, Gitta (1974). Into That Darkness: from Mercy Killing to Mass Murder. ISBN 0-07-056290-3.

- Gilead, Isaac; Haimi, Yoram; Mazurek, Wojciech (2009), Excavating Nazi Extermination Centres. Present Pasts, Vol 1. Published by Ubiquity Press,

ISSN 1759-2941

- Zielinski, Andrew (2003), "Conversations with Regina", Zedartz – Hyde Park Press Adelaide.

ISBN 0-9750766-0-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sobibór extermination camp. |

Sobibor on the Yad Vashem website

SOBIBOR at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The Sobibor Death Camp at HolocaustResearchProject.org

Sobibor Archaeological Project at Israel Hayom- Archaeological Excavations at Sobibór Extermination Site

Survivor Thomas Blatt, 18-minute audio interview by WMRA

- International archeological research in the area of the former German-Nazi extermination camp in Sobibór.

Onderzoek – Vernietigingskamp Sobibor (records of testimonies, transportation lists and other documents, from the archives of the NIOD Instituut voor Oorlogs-, Holocaust- en Genocidestudies, Netherlands)

Archaeological Excavations at Sobibór Extermination Site, at Yad Vashem website