Roland

A statue of Roland at Metz railway station, France

Roland (Frankish: "*Hrōþiland"; Latin: "Hruodlandus", "Rotholandus"; Italian: "Orlando", "Rolando"; died 15 August 778) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the Matter of France. The historical Roland was military governor of the Breton March, responsible for defending Francia's frontier against the Bretons. His only historical attestation is in Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni, which notes he was part of the Frankish rearguard killed by rebellious Basques in Iberia at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass.

The story of Roland's death at Roncevaux Pass was embellished in later medieval and Renaissance literature. The first and most famous of these epic treatments was the Old French Chanson de Roland of the 11th century.

Two masterpieces of Italian Renaissance poetry, the Orlando Innamorato and Orlando Furioso (by Matteo Maria Boiardo and Ludovico Ariosto), are further detached from history than the earlier Chansons, similarly to the later Morgante by Luigi Pulci. Roland is poetically associated with his sword Durendal, his horse Veillantif, and his oliphant horn.

Contents

1 History

2 Legacy

3 Figure of speech

4 Notes

5 References

6 External links

History

Attributed arms according to Michel Pastoureau:[1]Échiqueté d'argent et de sable

The only historical mention of the actual Roland is in the Vita Karoli Magni by Charlemagne's courtier and biographer Einhard. Einhard refers to him as Hruodlandus Brittannici limitis praefectus ("Roland, prefect of the borders of Brittany"), indicating that he presided over the Breton March, Francia's border territory against the Bretons.[2] The passage, which appears in Chapter 9, mentions that Hroudlandus (a Latinization of the Frankish *Hrōþiland, from *hrōþi, "praise"/"fame" and *land, "country") was among those killed in the Battle of Roncevaux Pass:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

While he was vigorously pursuing the Saxon war, almost without a break, and after he had placed garrisons at selected points along the border, [Charles] marched into Spain [in 778] with as large a force as he could mount. His army passed through the Pyrenees and [Charles] received the surrender of all the towns and fortified places he encountered. He was returning [to Francia] with his army safe and intact, but high in the Pyrenees on that return trip he briefly experienced the Basques. That place is so thoroughly covered with thick forest that it is the perfect spot for an ambush. [Charles's] army was forced by the narrow terrain to proceed in a long line and [it was at that spot], high on the mountain, that the Basques set their ambush. [...] The Basques had the advantage in this skirmish because of the lightness of their weapons and the nature of the terrain, whereas the Franks were disadvantaged by the heaviness of their arms and the unevenness of the land. Eggihard, the overseer of the king's table, Anselm, the count of the palace, and Roland, the lord of the Breton March, along with many others died in that skirmish. But this deed could not be avenged at that time, because the enemy had so dispersed after the attack that there was no indication as to where they could be found.[3]

Roland was evidently the first official appointed to direct Frankish policy in Breton affairs, as local Franks under the Merovingian dynasty had not previously pursued any specific relationship with the Bretons. Their frontier castle districts such as Vitré, Ille-et-Vilaine, south of Mont Saint-Michel, are now divided between Normandy and Brittany. The distinctive culture of this region preserves the present-day Gallo language and legends of local heroes such as Roland. Roland's successor in Brittania Nova was Guy of Nantes, who like Roland, was unable to exert Frankish expansion over Brittany and merely sustained a Breton presence in the Carolingian Empire.

According to legend, Roland was laid to rest in the basilica at Blaye, near Bordeaux, on the site of the citadel.

Legacy

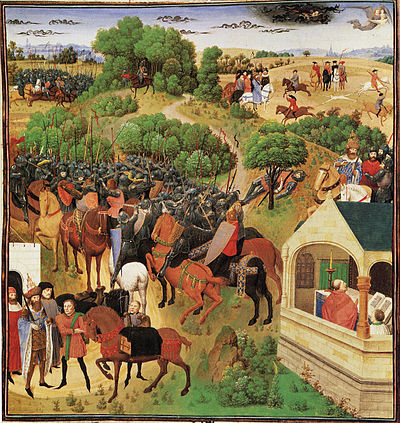

The eight phases of The Song of Roland in one picture

Composed in 1098, the first page of the Chanson de Roland (Song of Roland)

Roland was a popular and iconic figure in medieval Europe and its minstrel culture. Many tales made him a nephew of Charlemagne and turned his life into an epic tale of the noble Christian killed by Islamic forces, which forms part of the medieval Matter of France.

The tale of Roland's death is retold in the 11th-century poem The Song of Roland, where he is equipped with the olifant (a signalling horn) and an unbreakable sword, enchanted by various Christian relics, named Durendal. The Song contains a highly romanticized account of the Battle of Roncevaux Pass and Roland's death, setting the tone for later fantastical depiction of Charlemagne's court.

It was adapted and modified throughout the Middle Ages, including an influential Latin prose version Historia Caroli Magni (latterly known as the Pseudo-Turpin Chronicle), which also includes Roland's battle with a Saracen giant named Ferracutus who is only vulnerable at his navel. The story was later adapted in the anonymous Franco-Venetian epic L'Entrée d'Espagne (c. 1320) and in the 14th-century Italian epic La Spagna, attributed to the Florentine Sostegno di Zanobi and likely composed between 1350 and 1360.

Other texts give further legendary accounts of Roland's life. His friendship with Olivier and his engagement with Olivier's sister Aude are told in Girart de Vienne by Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube. Roland's youth and the acquisition of his horse Veillantif and sword are described in Aspremont. Roland also appears in Quatre Fils Aymon, where he is contrasted with Renaud de Montauban against whom he occasionally fights.

In Norway, the tales of Roland are part of the 13th-century Karlamagnús saga.

In the Divine Comedy Dante sees Roland, named Orlando as it is usual in Italian literature, in the Heaven of Mars together with others who fought for the faith.

Roland appears in Entrée d'Espagne, a 14th-century Franco-Venetian chanson de geste (in which he is transformed into a knight errant, similar to heroes from the Arthurian romances) and La Spagna, a 14th-century Italian epic.

From the 15th century onwards, he appears as a central character in a sequence of Italian verse romances as "Orlando", including Morgante by Luigi Pulci, Orlando Innamorato by Matteo Maria Boiardo, and Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto. (See below for his later history in Italian verse.) The Orlandino of Pietro Aretino then waxed satirical about the "cult of personality" of Orlando the hero. The Orlando narrative inspired several composers, amongst whom were Claudio Monteverdi, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Antonio Vivaldi and George Frideric Handel, who composed an Italian-language opera with Orlando.

In Germany, Roland gradually became a symbol of the independence of the growing cities from the local nobility. In the late Middle Ages many cities featured defiant statues of Roland in their marketplaces. The Roland in Wedel was erected in 1450 as symbol of market and Hanseatic justice, and the Roland statue in front of Bremen City Hall (1404) has been listed together with the city hall itself on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites since 2004.

In Aragón there are several placenames related to Roldán or Rolando: la Breca de Roldán (la Brecha de Roldán in Spanish, La Brèche de Roland in French) and Salto d´o Roldán (El Salto de Roldán in Spanish).

In Catalonia Roland (or Rotllà, as it is rendered in Catalan) became a legendary giant. Numerous places in Catalonia (both North and South) have a name related to Rotllà. In step with the trace left by the character in the whole Pyrenean area, Basque Errolan turns up in numerous legends and place-names associated with a mighty giant, usually a heathen, capable of launching huge stones. The Basque word erraldoi (giant) stems from Errol(d)an, as pointed out by the linguist Koldo Mitxelena.[4]

In the Faroe Islands Roland appears in the ballad of "Runtsivalstríðið" (Battle of Roncevaux).

A statue of Roland also stands in the city of Rolândia in Brazil. This city was established by German immigrants, many of whom were refugees from Nazi Germany, who named their new home after Roland to represent freedom.[5]

Figure of speech

The English expression "to give a Roland for an Oliver", meaning either to offer a quid pro quo or to give as good as one gets, recalls the Chanson de Roland and Roland's companion Oliver.[6]

Notes

^ Pastoureau, Michel (2009). L'Art de l'héraldique au Moyen Âge (in French). Paris: éditions du Seuil. p. 197. ISBN 978-2-02-098984-8..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hruodlandus is the earliest Latinised form of his Frankish name Hruodland. It was later Latinised as Rolandus and has been translated into many languages for literary purposes: Italian: Orlando or Rolando, Dutch: Roeland, Spanish: Roldán or Rolando, Basque: Errolan, Portuguese: Roldão or Rolando, Occitan: Rotland, Catalan: Rotllant or Rotllà.

^ Dutton, Paul Edward, ed. and trans. Charlemagne's Courtier: The Complete Einhard, pp. 21–22. Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Broadview Press, 1998. Einhard at the Latin Library.

^ "Mintzoaren memoria". El País. 2004-09-13. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

^ Mainka, Peter Johann (2008), Roland und Rolândia im Nordosten von Paranà: Gründungs- und Frühgeschichte einer deutschen Kolonie in Brasilien (1932– 1944/45), Cultura Acadêmica, ISBN 978-8598605272

^ Brown, Lesley, ed. (1993), The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 2, Clarendon Press, p. 2618

References

- Lojek, A. – Adamová, K.: "About Statues of Rolands in Bohemia", Journal on European History of Law, Vol. 3/2012, No. 1, s. 136–138. (ISSN 2042-6402).

- Adriana Kremenjas-Danicic (Ed.): Roland's European Paths. Europski dom Dubrovnik, Dubrovnik 2006 (

ISBN 953-95338-0-5). - Susan P. Millinger, "Epic Values: The Song of Roland", in Jason Glenn (ed), The Middle Ages in Texts and Texture: Reflections on Medieval Sources (Toronto, University of Toronto, 2012).

External links

. The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

. The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 464–465.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 464–465.