Bass guitar

Fender Precision Bass-style instrument | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bass, electric bass guitar, electric bass |

| Classification | String instrument (fingered or picked; strummed) |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322 (Composite chordophone) |

| Inventor(s) | Paul Tutmarc, Leo Fender |

| Developed | 1930s |

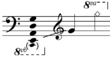

| Playing range | |

(a standard tuned 4-string bass guitar) | |

| Related instruments | |

| |

| Musicians | |

| |

The bass guitar (also known as electric bass, or simply bass) is a stringed instrument similar in appearance and construction to an electric guitar, except with a longer neck and scale length, and four to six strings or courses. The bass guitar is a transposing instrument, as it is notated in bass clef an octave higher than it sounds. It is played primarily with the fingers or thumb, or strking with a pick. The electric bass guitar has pickups and must be connected to an amplifier and speaker to be loud enough to compete with other instruments.

Since the 1960s, the bass guitar has largely replaced the double bass in popular music as the bass instrument in the rhythm section.[1] While types of basslines vary widely from one style of music to another, the bassist usually plays a similar role: anchoring the harmonic framework and establishing the beat. Many styles of music include the bass guitar, and it is occasionally a soloing instrument.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 History

2.1 1930s–1940s

2.2 1950s

2.3 1960s

2.4 1970s

2.5 1980s–present

3 Design considerations

3.1 Fretted and fretless basses

3.2 Strings and tuning

3.2.1 Alternative range approaches

3.3 Alternative neck designs

4 Pickups and amplification

4.1 Magnetic pickups

4.2 Non-magnetic pickups

4.3 Amplification and effects

5 Performance techniques

5.1 Slap and pop

5.2 Picking techniques

5.3 Palm-muting techniques

5.4 Fretting techniques

5.5 Two-handed tapping

5.6 Strumming

5.7 Chucking

6 Uses

6.1 Popular and traditional music

6.2 Solos in metal, funk and progressive rock

6.3 Jazz and jazz fusion

6.4 Use in contemporary classical music

7 Pedagogy and training

7.1 Formal training

7.2 Informal training

8 See also

9 Footnotes and references

9.1 Sources

10 Further reading

11 External links

Terminology

According to the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, an "Electric bass guitar [bass guitar] [is] a Guitar, usually with four heavy strings tuned E1'-A1'-D2-G2." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London, 2001)

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians defines bass as "Bass (iv). A contraction of Double bass or Electric bass guitar." Ibid. The proper term is "electric bass", and it is often miscalled "bass guitar", according to Tom Wheeler, The Guitar Book, pp 101–2. Guitars by Evans and Evans, page 342, agrees. Although "electric bass" is one of the common names for the instrument, "bass guitar" or "electric bass guitar" are commonly used and some authors claim that they are historically accurate (e.g., "How The Fender Bass Changed The World" in the references section).

The four-string bass is usually tuned the same as the double bass (Bass guitar/double bass tuning E1 = 41.20 Hz, A1 = 55 Hz, D2 = 73.42 Hz, G2 = 98 Hz + optional low B0 = 30.87 Hz) which corresponds to pitches one octave lower than the four lowest pitched strings of a guitar (E, A, D, and G). (Standard guitar tuning E2 = 82.41 Hz, A2 = 110 Hz, D3 = 146.8 Hz, G3 = 196 Hz, B3 = 246.9 Hz, E4 = 329.6 Hz).

History

1930s–1940s

Musical instrument inventor Paul Tutmarc outside his music store in Seattle, Washington

In the 1930s, musician and inventor Paul Tutmarc of Seattle, Washington, developed the first electric string bass in its modern form, a fretted instrument designed to be played horizontally. The 1935 sales catalog for Tutmarc's electronic musical instrument company, Audiovox, featured his "Model 736 Bass Fiddle", a four-stringed, solid-bodied, fretted electric bass instrument with a 30 1⁄2-inch (775-millimetre) scale length, and a single pick up<

.[2] The adoption of a guitar's body shape made the instrument easier to hold and transport than any of the existing stringed bass instruments. The addition of frets enabled bassists to play in tune more easily than on fretless acoustic or electric upright basses. Around 100 of these instruments were made during this period.[3] Audiovox also sold their “Model 236” bass amplifier.[4]

Around 1947, Tutmarc's son, Bud, began marketing a similar bass under the Serenader brand name, prominently advertised in the nationally distributed L. D. Heater Music Company wholesale jobber catalogue of 1948. However, the Tutmarc family inventions did not achieve market success.

1950s

An early Fender Precision Bass

In the 1950s, Leo Fender and George Fullerton developed the first mass-produced electric bass guitar.[5] The Fender Electric Instrument Manufacturing Company began producing the Precision Bass in October 1951. The "P-bass" evolved from a simple, un-contoured "slab" body design and a single coil pickup similar to that of a Telecaster, to something more like a Fender Stratocaster, with a contoured body design, edges beveled for comfort, and a split single coil pickup.

Design patent issued to Leo Fender for the second-generation Precision Bass

The "Fender Bass" was a revolutionary new instrument for gigging musicians. In comparison with the large, heavy upright bass, which had been the main bass instrument in popular music from the early 1900s to the 1940s, the bass guitar could be easily transported to shows. When amplified, the bass guitar was also less prone than acoustic basses

to unwanted audio feedback.[6]

In 1953 Monk Montgomery became the first bassist to tour with the Fender bass guitar, in Lionel Hampton's postwar big band.[7] Montgomery was also possibly the first to record with the bass guitar, on July 2, 1953 with The Art Farmer Septet.[8] Roy Johnson (with Lionel Hampton), and Shifty Henry (with Louis Jordan & His Tympany Five), were other early Fender bass pioneers.[5]Bill Black, playing with Elvis Presley, switched from upright bass to the Fender Precision Bass around 1957.[9] The bass guitar was intended to appeal to guitarists as well as upright bass players, and many early pioneers of the instrument, such as Carol Kaye, Joe Osborn, and Paul McCartney were originally guitarists.[10]

In 1953, following Fender's lead, Gibson released the first short-scale violin-shaped electric bass, with an extendable end pin so a bassist could play it upright or horizontally. Gibson renamed the bass the EB-1 in 1958.[11] Also in 1958, Gibson released the maple arched-top EB-2 described in the Gibson catalogue as a "hollow-body electric bass that features a Bass/Baritone pushbutton for two different tonal characteristics".[12] In 1959 these were followed by the more conventional-looking EB-0 Bass. The EB-0 was very similar to a Gibson SG in appearance (although the earliest examples have a slab-sided body shape closer to that of the double-cutaway Les Paul Special).

Gibson EB-3

Whereas Fender basses had pickups mounted in positions in between the base of the neck and the top of the bridge, many of Gibson's early basses featured one humbucking pickup mounted directly against the neck pocket. The EB-3, introduced in 1961, also had a "mini-humbucker" at the bridge position. Gibson basses tended to be smaller, sleeker instruments with a shorter scale length than the Precision; Gibson did not produce a 34-inch (864 mm)-scale bass until 1963 with the release of the Thunderbird, which was also the first Gibson bass to use two humbucking pickups in a more traditional position, about halfway between the neck and bridge.

A number of other companies also began manufacturing bass guitars during the 1950s: Kay in 1952, Hofner and Danelectro in 1956, Rickenbacker in 1957 and Burns/Supersound in 1958.[9] 1956 saw the appearance at the German trade fair "Musikmesse Frankfurt" of the distinctive Höfner 500/1 violin-shaped bass made using violin construction techniques by Walter Höfner, a second-generation violin luthier.[13] The design was eventually known popularly as the "Beatle Bass", due to its endorsement and use by Beatles bassist Paul McCartney. In 1957, Rickenbacker introduced the model 4000,[14] the first bass to feature a neck-through-body design in which the neck is part of the body wood. The Fender and Gibson versions used bolt-on and glued-on necks.

1960s

With the explosion of the popularity of rock music in the 1960s, many more manufacturers began making electric basses, including Yamaha, Teisco and Guyatone.

Introduced in 1960, the Fender Jazz Bass was first known as the "Deluxe Bass," intended to accompany the Jazzmaster guitar. The "J-bass" featured two single-coil pickups, one close to the bridge and one in the Precision bass's split coil pickup position. The earliest production Jazz basses had a "stacked"[further explanation needed] volume and tone control for each pickup; this was soon changed to the familiar configuration of a volume control for each pickup, and a single passive tone control.

The Jazz Bass's neck was narrower at the nut than the Precision bass — 1 1⁄2 inches (38 mm) versus 1 3⁄4 inches (44 mm) — allowing for easier access to the lower strings and an overall spacing and feel closer to that of an electric guitar, allowing trained guitarists to transition to the bass guitar more easily. Another visual difference that set the Jazz Bass apart from the Precision is its "offset-waist" body.

1970s Fender Jazz Bass with maple fretboard

Pickup shapes on electric basses are often referred to as "P" or "J" pickups in reference to the visual and electrical differences between the Precision Bass and Jazz Bass pickups. In the 1950s and 1960s, all bass guitars were often called the "Fender bass", due to Fender's early dominance in the market.

Providing a more "Gibson-scale" instrument, rather than the 34 inches (864 mm) Jazz and Precision, Fender produced the Mustang Bass, a 30-inch (762 mm) scale-length instrument.

The Fender VI, a baritone guitar, was tuned one octave lower than standard guitar tuning. It was released in 1961, and was briefly favored by Jack Bruce of Cream.[15]

Gibson introduced its short-scale 30 1⁄2-inch (775 mm) EB-3 in 1961, also used by Jack Bruce.[16]

1970s

Rickenbacker 4001 bass

In 1971, Alembic established what became known as "boutique" or "high-end" electric bass guitars. These expensive, custom-tailored instruments, as used by Phil Lesh, Jack Casady, and Stanley Clarke, featured unique designs, premium hand-finished wood bodies, and innovative construction techniques such as multi-laminate neck-through-body construction and graphite necks. Alembic also pioneered the use of onboard electronics for pre-amplification and equalization. Active electronics increase the output of the instrument, and allow more options for controlling tonal flexibility, giving the player the ability to amplify as well as to attenuate certain frequency ranges while improving the overall frequency response (including more low-register and high-register sounds). 1973 saw the UK company Wal begin production of a their own range of active basses, and In 1974 Music Man Instruments, founded by Tom Walker, Forrest White and Leo Fender, introduced the StingRay, the first widely produced bass with active (powered) electronics built into the instrument. Basses with active electronics can include a preamplifier and knobs for boosting and cutting the low and high frequencies.

Specific bass brands/models became identified with particular styles of music, such as the Rickenbacker 4001 series, which became identified with progressive rock bassists like Chris Squire of Yes, and Geddy Lee of Rush, while the StingRay was used by funk/disco players such Louis Johnson of the funk band The Brothers Johnson and Bernard Edwards of Chic. The 4001 stereo bass was introduced in the late 1960s; it can be heard on the Beatles' "I Am The Walrus".[17]

In the mid-1970s, Alembic and other high-end manufacturers, such as Tobias, began offering five-string basses, with a very low "B" string. In 1975, bassist Anthony Jackson commissioned luthier Carl Thompson to build a six-string bass tuned (low to high) B0, E1, A1, D2, G2, C3, adding a low B string and a high C string. These five- and six-string "extended-range basses" would become popular with session bassists, reducing the need for re-tuning to alternate detuned configurations like "drop D", and also allowing the bassist to play more notes from the same fretting position with fewer shifts up and down the fingerboard, a crucial benefit for a session player sightreading basslines at a recording session.

1980s–present

Early 1980s-era Steinberger headless bass. The tuning machines are at the heel of the instrument, where the bridge is usually located.

In the 1980s, bass designers continued to explore new approaches. Ned Steinberger introduced a headless bass in 1979 and continued his innovations in the 1980s, using graphite and other new materials and (in 1984) introducing the TransTrem tremolo bar. In 1982, Hans-Peter Wilfer founded Warwick, to make a European bass, as the market at the time was dominated by Asian and American basses. Their first bass was the Streamer Bass, which is similar to the Spector NS. In 1987, the Guild Guitar Corporation launched the fretless Ashbory bass, which used silicone rubber strings and a piezoelectric pickup to achieve an "upright bass" sound with a short 18-inch (457 mm) scale length. In the late 1980s, MTV's "Unplugged" show, which featured bands performing with acoustic instruments, helped to popularize hollow-bodied acoustic bass guitars amplified with piezoelectric pickups built into the bridge of the instrument.

During the 1990s, as five-string basses became more widely available and more affordable, an increasing number of bassists in genres ranging from metal to gospel began using five-string instruments for added lower range—a low "B" string. As well, onboard battery-powered electronics such as preamplifiers and equalizer circuits, which were previously only available on expensive "boutique" instruments, became increasingly available on mid-priced basses. From 2000 to the 2010s, some bass manufacturers included digital modelling circuits inside the instrument on more costly instruments to recreate tones and sounds from many models of basses (e.g., Line 6's Variax bass). A modelling bass can digitally emulate the tone and sound of many famous basses, ranging from a vintage Fender Precision to a Rickenbacker. However, as with the electric guitar, traditional "passive" bass designs, which include only pickups, tone and volume knobs (without a preamp or other electronics) remained popular. Reissued versions of vintage instruments such as the Fender Precision Bass and Fender Jazz Bass remained popular amongst new instrument buyers up to the 2010s. In 2011, a 60th Anniversary P-bass was introduced by Fender, along with the re-introduction of the short-scale Fender Jaguar Bass.

Design considerations

Bass bodies are typically made of wood, although other materials such as graphite (for example, some of the Steinberger designs) and other lightweight composite materials have been used. While a wide variety of woods are suitable for the body, neck, and fretboard, the most common woods used are those used for solid-body electric guitars: alder, ash or mahogany for the body, maple for the neck, and rosewood or ebony for the fretboard. For tonal or aesthetic reasons, luthiers more commonly experiment with different woods on basses than with electric guitars, and less-common woods like walnut and figured maple, as well as exotic woods like bubinga, wenge, koa, and purpleheart, are often used as accent woods in the neck or on the face of mid- to high-priced production basses. More expensive basses often feature exotic woods. For example, Alembic uses cocobolo as a body or top layer material because of its attractive grain. Warwick bass guitars are well known for exotic hardwoods, making most necks out of ovangkol, and fingerboards from wenge or ebony. Some makers use solid bubinga bodies for their tonal and aesthetic qualities.

Other design options include finishes, such as lacquer, wax and oil; flat and carved designs; luthier-produced custom-designed instruments; headless basses, which have tuning machines in the bridge of the instrument (e.g., Steinberger and Hohner designs) and artificial materials such as Luthite and Ebonol. The use of artificial materials allows for unique production techniques such as die-casting, to produce complex body shapes.

While most basses have solid bodies, they can also include hollow chambers to increase the resonance or reduce the weight of the instrument. Some basses are built with entirely hollow bodies, which change the tone and resonance of the instrument. Acoustic bass guitars have a hollow wooden body constructed similarly to an acoustic guitar, and are typically equipped with piezoelectric or magnetic pickups and amplified.

Some makers have used graphite composite to make lightweight necks[18][better source needed] e.g., Status brand basses, which are made from graphite.

A common feature of more expensive basses is "neck-through" construction. Instead of milling the body from a single piece of wood (or "bookmatched" halves) and then attaching the neck into a pocket (so-called "bolt-on" design), neck-through basses are constructed first by assembling the neck, which may comprise one, three, five or more layers of wood in vertical stripes, which are longer than the length of the fretboard. To this elongated neck, the body is attached as two wings, which may also be made up of several layers. The entire bass is then milled and shaped. Neck-through construction advertisements claim this approach provides better sustain and a mellower tone than bolt-on neck construction. While neck-through construction is most common in handmade "boutique" basses, some models of mass-produced basses such as Ibanez's BTB series also have neck-through construction. Bolt-on neck construction does not necessarily imply a cheaply made instrument; virtually all traditional Fender designs still use bolt-on necks, including its high-end instruments costing thousands of dollars, and many boutique luthiers such as Sadowsky build bolt-on basses as well as neck-through instruments.

The number of frets installed on a bass guitar neck may vary. The original Fender basses had 20 frets, and most bass guitars have between 20 and 24 frets or fret positions. Instruments with between 24 and 36 frets (2 and 3 octaves) also exist. Instruments with more frets are used by bassists who play bass solos, as more frets gives them additional upper range notes. When a bass has a large number of frets, such as a 36 fret instrument, the bass may have a deeper "cutaway" to enable the performer to reach the higher pitches. Like electric guitars, fretted basses typically have markers on the fingerboard and on the side of the neck to assist the player in determining where notes and important harmonic points are. The markers indicate the 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th fret and 12th fret (the 12th fret being the octave of the open string) and on the octave-or-more equivalents of the 3rd fret and as many additional positions as an instrument has frets for. Typically, one marker is on the 3rd, 5th, 7th and 9th fret positions and two markers on the 12th fret.

The "long scale necks" on the first Fender basses—34 inches (864 mm) — set the standard for electric basses, although 30-inch (762 mm) "short scale" instruments, such as the Höfner 500/1 "violin bass" played by Paul McCartney, and the Fender Mustang Bass are common. Short-scale instruments use the same E-A-D-G tuning as a regular long scale instrument. While 35-inch (889 mm), 35 1⁄2-inch (902 mm), and 36-inch (914 mm) scale lengths were once only available in "boutique" instruments, these "extra long" scale lengths became somewhat more common in the 2000s. This extra-long scale provides a higher string tension, which may yield a more defined, deep tone on the low "B" string of five- and six-stringed instruments (or detuned four-string basses).

Fretted and fretless basses

A fretless bass with flatwound strings; markers are inlaid into the side of the fingerboard, to aid the performer in finding the correct pitch.

Another design consideration for the bass is whether to use frets on the fingerboard. On a fretted bass, the metal frets divide the fingerboard into semitone divisions (as on an electric guitar or acoustic guitar). Fretless basses have a distinct sound, because the absence of frets means that the string must be pressed down directly onto the wood of the fingerboard with the fingers, as with the double bass. The string buzzes against the wood and is somewhat muted because the sounding portion of the string is in direct contact with the flesh of the player's finger. The fretless bass lets players use expressive approaches such as glissando (sliding up or down in pitch, with all of the pitches in between sounding), and vibrato (in which the player rocks a finger that is stopping a string to oscillate the pitch slightly). Fretless players can also play microtones, or temperaments other than equal temperament, such as just intonation.

While fretless basses are often associated with jazz and jazz fusion, bassists from other genres have used fretless basses, such as Freebo (country), Rick Danko (rock/blues), Rod Clements (folk), Steve DiGiorgio, Jeroen Paul Thesseling (metal), Tony Franklin (rock), and Colin Edwin (modern/progressive rock). Some bassists alternate between fretted and fretless basses in performances, according to the type of material or tunes they are performing, e.g., Pino Palladino or Tony Levin.

The first fretless bass guitar was made by Bill Wyman in 1961 when he converted a used UK-built ‘Dallas Tuxedo’ bass by removing the frets and filling in the slots with wood putty.[19][20] Wyman's early fretless bass can be heard on The Rolling Stones songs such as "Paint It, Black" and "Mother's Little Helper" from 1966. He is seen recording with the instrument in the 1968 film One Plus One a.k.a. Sympathy for the Devil.

The first production fretless bass was the Ampeg AUB-1 introduced in 1966, and Fender introduced a fretless Precision Bass in 1970. Around 1970, Rick Danko from The Band began to use an Ampeg fretless, which he modified with Fender pickups—as heard on the 1971 Cahoots studio album and the Rock of Ages album recorded live in 1971.[21][22] Danko said, "It's a challenge to play fretless because you have to really use your ear."[23] In the early 1970s, fusion-jazz bassist Jaco Pastorius coated the fingerboard of his de-fretted Fender Jazz Bass in epoxy resin, allowing him to use roundwound strings for a brighter sound. Pastorius used epoxy rather than varnish to obtain a glass-like finish suitable for the use of roundwound strings, which are otherwise much harder on the wood of the fingerboard. Some fretless basses have "fret line" markers inlaid in the fingerboard as a guide, while others only use guide marks on the side of the neck.

Tapewound (double bass type) and flatwound strings are sometimes used with the fretless bass so the metal string windings do not wear down the fingerboard. Tapewound and flatwound strings have a distinctive tone and sound. Some fretless basses have epoxy-coated fingerboards, or fingerboards made of an epoxy composite like micarta, to increase the fingerboard's durability, enhance sustain, and give a brighter tone.

Strings and tuning

Tuning machines (with spiral metal worm gears) are mounted on the back of the headstock on the bass guitar neck

The standard design for the electric bass guitar has four strings, tuned E, A, D and G,[24] in fourths such that the open highest string, G, is an eleventh (an octave and a fourth) below middle C, making the tuning of all four strings the same as that of the double bass (E1–A1–D2–G2). This tuning is also the same as the standard tuning on the lower-pitched four strings on a six-string guitar, only an octave lower.

There is a range of different string types, which are available in many various metals, windings, and finishes. Each combination has specific tonal characteristics, interaction with pickups, and "feel" to the player's hands.

Variables include wrap finish (roundwound, flatwound, halfwound, ground wound, and pressure wound), as well as metal strings with different coverings (tapewound or plastic covered). In the 1950s and early 1960s, bassists mostly used flatwound strings with a smooth surface, which have a smooth, damped sound reminiscent of a double bass. In the late 1960s and 1970s, players began using roundwound bass strings, which produce a brighter tone similar to steel guitar strings, snd a brighter timbre (tone) with longer sustain than flatwounds.

A variety of tuning options and number of string courses (courses are when strings are put together in groups of two, often at the unison or octave) have been used to extend the range of the instrument, or facilitate different modes of playing, or allow for different playing sounds.

Four strings can obtain an extended lower range through thicker strings or "down-tuning." Tunings such as B–E–A–D (this requires a low "B" string in addition to the other three "standard" strings, and omits the G string), D–A–D–G (a "standard" set of strings, with only the lowest string detuned from E down to D), and D–G–C–F or C–G–C–F (a "standard" set of strings, all of which are detuned either a whole tone, or a whole tone for the three higher-pitched strings and two tones for the E, which is dropped to a low C) give bassists an extended lower range. A tenor bass tuning of A–D–G–C, in which the low E is omitted and a high C is added, provides a higher range. Tuning in fifths e.g., C–G–D–A (like a violoncello but an octave lower) gives an extended upper and lower range.

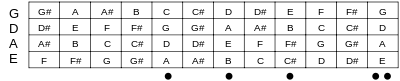

Note positions on a right-handed four-string bass in standard E–A–D–G tuning (from lowest-pitched string to the highest-pitched string, shown in sharps), shown up to the 12th fret, where the pattern repeats. The dots below the frets are often inlaid into the wood of bass necks, as a visual aid to help the player find different positions.

Note positions on a right-handed five-string bass in standard B–E–A–D–G tuning (from lowest-pitched string to the highest-pitched string, shown in flats), shown up to the 12th fret, where the pattern repeats. The dots below the frets are often inlaid into the wood of bass necks, as a visual aid to help the player find different positions.

Five strings usually tuned B0–E1–A1–D2–G2, providing extended lower range. The earliest commercial five-string bass was created by Fender in 1965. The Fender Bass V used the E–A–D–G–C tuning, but was unpopular and discontinued in 1970. This tenor tuning is still used by some jazz and soloing bassists. The low-B five-string was created by Jimmy Johnson in 1975, modifying an E–A–D–G–C five-string Alembic bass, with a different nut and a low-B string from GHS. Steinberger made a 5-string headless instrument called the L-2/5 in 1982, and later Yamaha offered its first production model as the BB5000 in 1984.

Washburn XB600, a six string bass

Six strings are usually tuned B0–E1–A1–D2–G2–C3—like a four-string bass with an additional low B string and a high C string. Some players prefer B0–E1–A1–D2–F♯2–B2, which preserves the intervals of standard six-string guitar tuning (an octave and a fourth lower) and makes the highest and lowest string the same note two octaves apart. While less common than four or five-string basses, they appear in Latin, jazz, and other genres, as well as in studio work where a session musician's single instrument must be highly versatile, and to facilitate sightreading in the recording studio. In 1974, Anthony Jackson worked with Carl Thompson to create the Contrabass guitar (BEADGC). Later, Jackson brought his ideas to Fodera and worked with Ken Smith to create a wider-spaced Contrabass guitar, which evolved to the modern six-string bass.

Eight and twelve-string models are both built on the same "course string" concept found on twelve-string guitars, where sets of strings are spaced together in groups of two or three that are primarily played simultaneously. These instruments typically have one of the strings in each course tuned an octave above the 'standard' string, although a fifth above is also used. Instruments with ten and fifteen strings, grouped in five courses, also exist, as do "extended-range basses" or ERBs with non-coursed string counts rivaling those of coursed-string basses.

A bass guitar headstock with detuner set to D position

Detuners are mechanical devices the player operates with the thumb on the fretting hand to quickly retune one or more strings to a pre-set lower pitch. The Hipshot typically drops the E-string down to D on a four-string bass. The Hipshot similarly drops the B-string down to a B♭ on five- or six-string basses. Rarely, some bassists (e.g., Michael Manring) add detuners to more than one string, or even more than one detuner to each string, so they can retune during a performance and access a wider range of chime-like harmonics.

Alternative range approaches

Some bassists use unusual tunings to extend the range or get other benefits, such as providing multiple octaves of notes at any given position, or a larger tonal range. Instrument types or tunings used for this purpose include basses with fewer than four strings (one-string bass guitars (Japanese manufacturer Atlansia offers one-, two- and three-stringed instruments [25]), two-string bass guitars, three-string bass guitars [tuned to E–A–D]) (Session bassist Tony Levin commissioned Music Man to build a three-string version of his favorite Stingray bass) and alternative tunings (e.g., tenor bass). Tuned A–D–G–C, like the top 4 strings of a six-string bass, or simply a standard four-string with the strings each tuned up an additional perfect fourth. Tenor bass is a tuning used by Stanley Clarke, Victor Wooten, and Stu Hamm.

Extended-range basses (ERBs) are basses with six to twelve strings—with the additional strings used for range rather than unison or octave pairs. A seven-string bass (B0–E1–A1–D2–G2–C3–F3) was built by luthier Michael Tobias in 1987 for bassist Garry Goodman. In 1999, South American bassist Igor Saavedra designed one of the first eight-string ERBs, and asked luthier Alfonso Iturra to build it for him.[26]

Conklin builds custom ERB basses. These have a low F♯ string below the B string, and the nine-string bass adds a low F♯ and a high B♭ string.

The Guitarbass is a ten-string instrument with four bass strings (tuned E–A–D–G) and six guitar strings (tuned E–A–D–G–B–E). The guitarbass has 10 strings on the same neck and body, but with separate scale lengths, bridges, fretboards, and pickups. It was created by John Woolley in 2005, based on a prototype built by David Minnieweather.[citation needed]

Luthier Michael Adler built the first eleven-string bass in 2004 and completed the first single-course 12-string bass in 2005. Adler's 11- and 12-string instruments have the same range as a grand piano. The Adler twelve-string has the same range as the Bösendorfer 290 grand piano with 97 notes. This was made possible by Goodman developing an A♭4 string for the 32-inch (813 mm) scale.

Subcontrabasses, such as C♯–F♯–B–E (the lowest string, C♯0 being at 17.32 Hz at around the limit of human hearing)((e.g., the Jauqo III-X from 2000 or the subbass guitar, E–A–D–G one octave below standard (E0 being at 20.6 Hz)) have been created.

Ibanez had released SR7VIISC in 2009, featuring a 30-inch (762 mm) scale and narrower width, and tuned as B–E–A–D–G–C–E; the company dubbed it a cross between bass and guitar.[27][better source needed]

A seven-string fretless bass

Since 2011, German bass luthier Warwick built several fretless Thumb NT 7 basses for Jeroen Paul Thesseling, featuring a 34-inch (864 mm) scale with subcontra tuning F♯–B–E–A–D–G–C.[28][29][30]

Yves Carbonne developed ten- and twelve-string fretless subbass guitars. These extended range subbasses, Legend X YC and Legend XII YC, were built by luthier from Barcelona.[31] The twelve-string Legend XII YC uses a new B string tuned at B−1 (15.4 Hz).[32][33]

In 2017, a 13 string bass tuned Ab00–Gb–Db–B–E–A–D–G–C–F–Bb–Eb–Ab4 was built by Prometeus guitars giving the fullest range to a string instrument allowable by current string technology.

A piccolo bass resembles a four-stringed electric bass guitar, but usually tuned one full octave higher than a normal bass. The first piccolo bass was constructed by luthier Carl Thompson for Stanley Clarke.[citation needed] To allow for the raised tuning, the strings are thinner, and the length of the neck (the scale) may be shorter. Several companies manufacture "piccolo" string sets that, with a different nut, can be put on any regular bass.

Joey DeMaio (Manowar) plays with four strings on his piccolo bass. Jazz bassist John Patitucci used a six-string piccolo bass, unaccompanied, on his song "Sachi's Eyes" on his album One More Angel. Michael Manring has used a five-string piccolo bass in several altered tunings. Michael uses D'Addario EXL 280 piccolo bass strings on his four-string hyperbass, made by Zon Guitars.[citation needed]

Alternative neck designs

A multi-scale fingerboard for guitars and bass guitars has the lower-pitched strings longer than the higher-pitched strings, with the frets set radially rather than parallel. Some players find that these "fanned" frets are more ergonomic, easier and more comfortable to play, lining up more naturally with the fretting hand as the player's shoulder rotates.[34] Other bassists believe that it evens out the tension across all of the strings, it evens the timbre across the strings, and extending the lower strings allows the string to produce harmonics that are closer to the fundamental. [35].

Dingwall Prima Artist - Fanned Frets Bass Guitar

Torzal Natural Twist is a bass guitar body and neck style invented by luthier Jerome Little from Amherst, Massachusetts. It consists of a neck rotated by a total of 35 degrees, with (+)15 degrees at the bridge and (-)20 at the nut. The designer claims that the ergonomic design increases efficiency of the hands, wrists and arms, which reduces the risk of developing repetitive strain injuries like carpal tunnel syndrome or tendonitis. This design is also beneficial to players who have already suffered from such injuries. This patented design differs from traditional bass guitar design by twisting the neck, and bringing the strings toward a more natural hand position at either end of the instrument. The rotation at either side of the instrument in the direction of the hand creates a neck plane that models the natural motion of the hand as it reaches outward. The fretboard also forms a straight line at the location of each string, which should improve the ease of performance.[36]

Pickups and amplification

Magnetic pickups

A lot of electric bass guitars use magnetic pickups. The vibrations of the instrument's ferrous metal strings within the magnetic field of the permanent magnets in magnetic pickups produce small variations in the magnetic flux threading the coils of the pickups. This in turn produces small electrical voltages in the coils. Many bass players connect the signal from the bass guitar's pickups to a bass amplifier and loudspeaker using a 1/4" patch cord. These low-level signals are then strengthened by the bass amp's preamplifier electronic circuits, and then amplified with the bass amp's power amplifier and played through one or more speaker(s) in a cabinet.

P-style, split-coil pickups

Most basses have a volume potentiometer ("pot" or "knob"), and a tone potentiometer that reduces (attenuates) the higher frequencies as it is turned. Basses with more than one pickup may have a selector switch or a "blend" potentiometer. Since the 1980s, basses are often available with battery-powered "active" electronics that boost the signal with a preamplifier and provide equalization controls to boost or cut bass and treble frequencies, or both. Some expensive basses have even more equalization options, such as bass, middle and treble.

"Precision" pickups (as introduced with the Fender Precision Bass) or "P-style" are two single-coil pickups, each offset a small amount along the length of the body so that each half is underneath two strings. The pair is considered a single pickup, as they are wired together in a humbucking configuration, grfeatly reducing noise from nearby electronic equipment and mains power. (Less common is the "single-coil P" pickup, as used on the original 1951 Precision bass. This is also known as the 'Vintage P' due to it being found on old vintage basses made before the invention of the split coil pickup. The "single-coil P" pickup is also used in the reissue and the Sting signature model.) P-style pickups are generally placed in the "neck" or "middle" position, but they are occasionally placed in the bridge position, or between two Jazz-style pickups.

Dual "J"-style pickups

"Jazz" pickups (as introduced with the Fender Jazz Bass) or "J-style", are wide eight-pole pickups that lie underneath all four strings. J pickups are typically single-coil designs, though there are a large number of humbucking designs. Traditionally, two of them are used, one near the bridge and another closer to the neck. As with the halves of P-pickups, the J-type pickups are wired in a humbucking manner so that, when used together, mains noise is greatly eliminated. J-type pickups tend to have a lower output and a thinner sound than P-type pickups. Many bassists combine a 'J' pickup at the bridge and a 'P' pickup at the neck and blend the two sounds.

A Yamaha BB404F, which has two passive single coil pickups

Dual coil "humbucker" pickups each have two signal-producing coils. Humbuckers also produce a higher output level than single-coil pickups, though many dual-coil pickups are marketed as retrofits for single-coil designs like the J pickup and advertise a similar output and tonal character to the stock single-coils. Dual coil pickups come in two main varieties; ceramic or ceramic and steel. Ceramic-only magnets have a relatively "harsher" sound than their ceramic and steel counterparts, and are thus used more commonly in heavier rock styles (heavy metal music, hardcore punk, etc.).

- A variant bass humbucker is used on Music Man basses; it has two coils, each with four large polepieces. This style is known as the "MM" pickup.. The most common configurations are a single pickup at the bridge, two pickups similar in placement to a Jazz Bass, or an MM pickup at the bridge with a single-coil pickup (often a "J") at the neck. These pickups can often be "tapped", meaning one of the two coils can be essentially turned off, giving a sound similar to a single-coil pickup.

"Soapbar" Pickups are so-named due to their resemblance to a bar of soap and originally referred to the Gibson P-90 guitar pickup. The term is also used to describe any pickup with a rectangular shape (no protruding screw mounting "ears" like on P, J or MM pickups) and no visible pole pieces. Most of the pickups falling into this category are humbucking, though a few single-coil soapbar designs exist. They are commonly found in basses designed for the rock and metal genres, such as Gibson, ESP Guitars, and Schecter, however they are also found on 5- and 6-string basses made popular by jazz and jazz fusion music, such as Yamaha's TRB and various Peavey model lines. 'Soapbar pickups' are also called 'extended housing pickups', because the rectangular shape is achieved simply by making the pickup cover longer or wider than it would have to be to only cover the pickup coils, and then the mounting holes are recessed inside these wider dimensions of the housing.

Many basses have just one pickup, typically a "P" or "MM" pickup, though single soapbars are not unheard of. Multiple pickups are also quite common, two of the most common configurations being two "J" pickups (as on the stock Fender Jazz), or a "P" near the neck and a "J" near the bridge (e.g., Fender Precision Bass Special, Fender Precision Bass Plus). A two-"soapbar" configuration is also very common, especially on basses by makes such as Ibanez and Yamaha. A combination of a J or other single-coil pickup at the neck and a Music Man-style humbucker in the bridge has become popular among boutique instrument builders, giving a very bright, focused tone that is good for jazz, funk and thumbstyle.

Some basses, particularly expensive boutique instruments or custom-made guitars, use more unusual pickup configurations. Examples include a soapbar and a "P" pickup (found on some Fender basses), bassist Stu Hamm's "Urge" basses, which have a "P" pickup sandwiched between two "J" pickups, and some of funk bassist Bootsy Collins' custom basses, which had as many as five J pickups. Another unusual pickup configuration is found on some of the custom basses that virtuoso bassist Billy Sheehan uses, in which there is one humbucker at the neck and a split-coil pickup at the middle position.

The placement of the pickup greatly affects the sound, timbre and tone of the instrument. A pickup near the neck joint emphasizes the fundamental and low-order harmonics and thus produces a deeper, bassier sound, while a pickup near the bridge emphasizes higher-order harmonics and makes a "tighter" or "sharper" sound. Usually basses with multiple pickups allow blending of the output from the pickups, with electrical and acoustical interactions between the two pickups (such as partial phase cancellations) allowing a range of tonal and timbral effects.

Non-magnetic pickups

The use of non-magnetic pickups allows bassists to use non-ferrous strings such as nylon, brass, polyurethane and silicone rubber. These materials produce different tones and, in the case of the polyurethane or silicone rubber strings, allow much shorter scale lengths.

Piezoelectric pickups (also called "piezo" pickups) are non-magnetic pickups that use a transducer to convert vibrations in the instrument's body or bridge into an electrical signal. They are typically mounted under the bridge saddle or near the bridge and produce a different tone from magnetic pickups, often similar to that of an acoustic bass. Piezo pickups are often used in acoustic bass guitars to allow for amplification without a microphone.

Optical pickups are another type of non-magnetic pickup. They use an infrared LED to optically track the movement of the string, similar to the mechanism of modern computer mice, which allows them to reproduce low-frequency tones at high volumes without the "hum" or excessive resonance associated with conventional magnetic pickups. Since optical pickups do not pick up high frequencies or percussive sounds well, they are commonly paired with piezoelectric pickups to fill in the missing frequencies. LightWave Systems builds basses with optical pickups.

Amplification and effects

Bass-stack amp and speaker configuration

Like the electric guitar, the electric bass guitar is almost always connected to an amplifier and a speaker with a patch cord for live performances. Electric bassists use either a "combo" amplifier, which combines an amplifier and a speaker in a single cabinet, or an amplifier and one or more speaker cabinets (typically stacked, with the amplifier sitting on the speaker cabinets, leading to the term "half-stack" for one cabinet setups and "full stack" for two).

In most genres, a "clean" bass tone (without any amplifier-induced "overdrive" or "distortion") is desirable, and so while guitarists often prefer the more desirable distorted tones of tube-transistor amplifiers, bassists commonly use solid-state amplifier circuitry to achieve the necessary high output wattages with less weight than tubes (though smaller tubes can often still be found in the low-power "preamplifier" sections of the system, where they provide a warmer, smoother character to the bass tone for relatively little additional weight). A few all-tube bass amplifiers are still available, notably from the Ampeg brand.

In some cases, to play the bass through PA amplification, it is plugged into a direct box or DI, which routes the signal to the bass amp while also sending the signal directly into a mixing console, and thence to the main and monitor speakers. When a recording of bass is being made, engineers may use a microphone set up in front of the amplifier's speaker cabinet for the amplified signal, a direct box signal that feeds the recording console, or a mix of both.

Various electronic bass effects such as preamplifiers, "stomp box"-style pedals and signal processors and the configuration of the amplifier and speaker can be used to alter the basic sound of the instrument. In the 1990s and early 2000s (decade), signal processors such as equalizers, overdrive devices (sometimes referred to as "fuzz bass" (The Beatles' 1965 album "Rubber Soul" uses the term "fuzz bass")), and compressors or limiters became increasingly popular. Modulation effects like chorus, flanging, phase shifting, and time effects such as delay and looping are less commonly used with bass than with electric guitar, but they are used in some styles of music.

Performance techniques

James Jamerson, influential Motown era bassist

In contrast to the upright bass ("double bass"), the electric bass guitar is played horizontally across the body, like a guitar. When the strings are plucked with the fingers (pizzicato), the index and middle fingers (and sometimes the thumb, ring, and little fingers as well) are used. James Jamerson, an influential bassist from the Motown era, played intricate bass lines using only his index finger, which he called "The Hook". There are also variations in how a bassist chooses to rest the right-hand thumb (or left thumb in the case of left-handed players). A player may rest his or her thumb on the top edge of one of the pickups or on the side of the fretboard, which is especially common among bassists who have an upright bass influence. Some bassists anchor their thumbs on the lowest string and move it off the lowest string when they need to play on the low string. Alternatively, the thumb can be rested loosely on the strings to mute the unused strings.

The string can be plucked (or picked) at any point between the bridge and the point where the fretting hand is holding down the string on the fingerboard; different timbres (tones) are produced depending on where along the string it is plucked. When plucked closer to the bridge, the string's harmonics are more pronounced, giving a brighter tone. Closer to the middle of the string, these harmonics are less pronounced, giving a more mellow, darker tone.

Bassists trying to emulate the sound of a double bass sometimes pluck the strings with their thumb and use palm-muting to create a short, "thumpy" tone. Monk Montgomery (who played in Lionel Hampton's big band) and Bruce Palmer (who performed with Buffalo Springfield) use thumb downstrokes. The use of the thumb was acknowledged by early Fender models, which came with a "thumbrest" or "Tug Bar" attached to the pickguard below the strings. Contrary to its name, this was not used to rest the thumb, but to provide leverage while using the thumb to pluck the strings. The thumbrest was moved above the strings in 1970s models (as a true thumbrest) and eliminated in the 1980s. Nevertheless, some reissued versions of vintage Fender basses in the 2010s do include a thumbrest.

Slap and pop

The slap and pop technique

The slap and pop method, or "thumbstyle", most associated with funk, uses tones and percussive sounds achieved by striking, thumping, or "slapping" a string with the thumb and snapping (or "popping") a string or strings with the index or middle fingers. Bassists often interpolate left hand-muted "ghost notes" between the slaps and pops to achieve a rapid percussive effect, and after a note is slapped or popped, the fretting hand may cause other notes to sound by using "hammer-ons", "pull-offs", or a left-hand glissando (slide). Larry Graham of Sly and the Family Stone and Graham Central Station was an early innovator of the slap style, and Louis Johnson of The Brothers Johnson is also credited as an early slap bass player.

Slap and pop style is also used by many bassists in other genres, such as rock (e.g., J J Burnel and Les Claypool), metal (e.g., Eric Langlois, Martin Mendez, Fieldy and Ryan Martinie), and jazz fusion (e.g., Marcus Miller, Victor Wooten and Alain Caron). Slap style playing was popularized throughout the 1980s and early 1990s by pop bass players such as Mark King (from Level 42) and rock bassists such as with Pino Palladino (currently a member of the John Mayer Trio and bassist for The Who),[37]Flea (from the Red Hot Chili Peppers), Billy Gould (from Faith No More) and Alex Katunich (from Incubus). Spank bass developed from the slap and pop style and treats the electric bass as a percussion instrument, striking the strings above the pickups with an open palmed hand. Wooten popularized the "double thump," in which the string is slapped twice, on the upstroke and a downstroke (for more information, see Classical Thump). A rarely used playing technique related to slapping is the use of wooden dowel "funk fingers", an approach popularized by Tony Levin.

Picking techniques

A pick (or plectrum) produces a more pronounced attack, for speed, or personal preference. Bass with a pick is primarily associated with rock and punk rock, but players in other styles also use them. Picks can be used with alternating downstrokes and upstrokes, or with all downstrokes for a more consistent attack. The pick is usually held with the index and thumb, with the up-and-down plucking motion supplied by the wrist.

There are many varieties of picks available, but due to the thicker, heavier strings of the electric bass, bassists tend to use heavier picks than those used for electric guitar, typically ranging from 1.14 mm–3.00 mm (3.00 is unusual). Different materials are used for picks, including plastic, nylon, rubber, and felt, all of which produce different tones. Felt and rubber picks sound closer to a fingerstyle tone.

Paul McCartney mutes strings with picking hand.

Palm-muting techniques

Palm-muting is a widely used bass technique. The outer edge of the palm of the picking hand is rested on the bridge while picking, and "mutes" the strings, shortening the sustain time. The harder the palm presses, or the more string area that is contacted by the palm, the shorter the string's sustain. The sustain of the picked note can be varied for each note or phrase. The shorter sustain of a muted note on an electric bass can be used to imitate the shorter sustain and character of an upright bass. Palm-muting is commonly done while using a pick, but can also be done without a pick, as when doing down-strokes with the thumb.

One prominent example of the pick/palm-muting combination is Paul McCartney, who has used this technique for decades. Sting also uses palm-muting, but often without a pick, using the thumb and first finger to pluck.

Fretting techniques

The fretting hand—the left hand for right-handed bass players and right hand for left-handed bass players—presses down the strings to play different notes and shape the tone or timbre of a plucked or picked note. One fretting technique is a finger per fret, where each finger in the fretting hand plays one fret in a given position, giving the advantage that full chromatic scale of over an octave and a half can be played with no up-down wrist movement. Also, the double bass-style technique can be used for fretting. This technique involves using four fingers in the space of three frets, especially in the lower positions (i.e., the fretting positions closer to the nut, where the space between notes is the widest). When considering the spacing between notes, this is a comfortable distance for the average person's hand size, however it requires more up-down hand movements. The main advantage of the "four fingers in three frets technique is less tendon strain, leading to a diminished likelihood of Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI). The image below (of a bassist performing tapping) shows the four-in-three.

A player can use the fretting hand to change a sounded note, either by fully muting it after plucking it, or by partially muting it near the bridge to reduce volume, or make the note fade faster. The fretting hand often mutes strings that are not being played to stop sympathetic vibrations, particularly when the player wants a "dry" or "focused" sound. On the other hand, the sympathetic resonance of harmonically related strings are sometimes desirable. In these cases, a bassist can fret harmonically related notes. For example, while fretting a sustained "F" (on the third fret of the "D" string), underneath an F major chord being played by a piano player, a bassist might hold down the "C" and low "F" below this note so their harmonics sound sympathetically.

The fretting hand can add vibrato to a plucked or picked note, either a gentle, narrow vibrato or a more exaggerated, wide vibrato with bigger pitch variations. For fretted basses, vibrato is always an alternation between the pitch of the note and a slightly higher pitch. For fretless basses, the player can use this style of vibrato, or they can alternate between the note and a slightly lower pitch, as is done with the double bass and on other unfretted stringed instruments. While vibrato is mostly done on "stopped" notes—that is, notes that are pressed down on the fingerboard—open strings can also be vibratoed by pressing down on the string behind the nut. As well, the fretting hand can be used to "bend" a plucked or picked note up in pitch, by pushing or pulling the string so that the note sounds at a higher pitch. To create the opposite effect, a "bend down", the string is pushed to a higher pitch before being plucked or picked and then allowed to fall to the lower, regular pitch after it is sounded. Though rare, some bassists may use a tremolo bar-equipped bass to produce the same effect.

In addition to pressing down one note at a time, bassists can also press down several notes at one time with their fretting hand to perform a double stop (two notes at once) or a chord. While double stops and chords are used less often by bassists than by electric guitarists playing rhythm guitar, a variety of double stops and chords can be performed on the electric bass. Some double stops used by bassists include octaves. Chords can be especially with effective on instruments with higher ranges such as six-string basses. Another variation to fully pressing down a string is to gently graze the string with the finger at the harmonic node points on the string, which creates chime-like upper partials (also called "overtones"). Glissando is an effect in which the fretting hand slides up or down the neck, which can be used to create a slide in pitch up or down. A subtle glissando can be performed by moving the fretting hand without plucking or picking the string; for a more pronounced effect, the string is plucked or picked first, or, in a metal or hardcore punk context, a pick may be scraped along the sides of the lower strings.

The tapping technique

The fretting hand can also be used to sound notes, either by plucking an open string with the fretting hand, or, in the case of a string that has already been plucked or picked, by "hammering on" a higher pitch or "pulling off" a finger to pluck a lower fretted or open stringed note. Jazz bassists use a subtle form of fretting hand pizzicato by plucking a very brief open string grace note with the fretting hand right before playing the string with the plucking hand. When a string is rapidly hammered on, the note can be prolonged into a trill.

Two-handed tapping

In the two-handed tapping styles, bassists use both hands to play notes on the fretboard by rapidly pressing and holding the string to the fret. Instead of plucking or picking the string to create a sound, in this technique, the action of striking the string against the fret or the fretboard creates the sound. Since two hands can be used to play on the fretboard, this makes it possible to play interweaving contrapuntal lines, to simultaneously play a bass line and a simple chord, or play chords and arpeggios. Bassist John Entwistle of The Who tapped percussively on the strings, causing them to strike the fretboard with a twangy sound to create drum-style fills.[citation needed] Players noted for this technique include Cliff Burton, Billy Sheehan, Stuart Hamm, John Myung, Victor Wooten, Les Claypool, Mark King, and Michael Manring. The Chapman Stick and Warr Guitars are string instruments specifically designed to play using two-handed tapping.

Strumming

Strumming, usually with finger nails, is a common technique on acoustic guitar, but it is not a commonly used technique for bass. However, notable examples are Stanley Clarke's bass playing on the introduction to "School Days", on the album of the same name,[38] and Lemmy who was noted for his use of chords, often playing the bass like a rhythm guitar.

Chucking

Bernard Edwards (Chic) sometimes used a technique called chucking to pluck the bass strings with the forefinger of his right hand,[39] in a manner similar to how strings are plucked with a plectrum.[40] Chucking uses the soft part of the forefinger and the nail of the forefinger to alternately strike the string in an up-down manner. The thumb supports the forefinger at the first joint, as though using an invisible plectrum. With a flexible wrist action, chucking facilitates rapid rhythmic sequences of notes played on different strings, particular notes that are an octave apart. Chucking is distinguished from plucking in that the attack is softer with a sound closer to that produced by the use of fingers. Chucking allows a mix of plucking and finger techniques on a given song, without having to take up or put down a plectrum. Examples of Edwards’ use of chucking on his Music Man Stingray bass can be heard on the intro and solo section of "Everybody Dance" and the foundation bass line of "Dance Dance Dance".

Uses

Popular and traditional music

Popular music bands and rock groups use the bass guitar as a member of the rhythm section, which provides the chord sequence or "progression" and sets out the "beat" for the song. The rhythm section typically consists of a rhythm guitarist or electric keyboard player, or both, a bass guitarist and a drummer; larger groups may add additional guitarists, keyboardists, or percussionists.

Bassists often play a bass line composed by an arranger, songwriter or composer of a song—or, in the case of a cover song, the bass line from the original. In other bands—e.g., jazz-rock bands that play from lead sheets and country bands using the Nashville number system—bassists are expected to improvise or prepare their own part to fit the song's chord progression and rhythmic style.

A simple pop bass line over a D major progression

Types of bass lines vary widely, depending on musical style. However, the bass guitarist generally fulfills a similar role: anchoring the harmonic framework (often by emphasizing the roots of the chord progression) and laying down the beat in collaboration with the drummer and other rhythm section instruments. The importance of the bass guitarist and the bass line varies in different styles of music. In some pop styles, such as 1980s-era pop and musical theater, the bass sometimes plays a relatively simple part as the music emphasizes vocals and melody instruments. In contrast, in reggae, funk, or hip-hop, entire songs may center on the bass groove, and the bass line is usually prominent in the mix.

In traditional music such as country music, folk rock, and related styles, the bass often plays the roots and fifth (typically the fifth below the root) of each chord in alternation. In these styles, bassists often use scalar "walkups" or "walkdowns" when there is a chord change. In Chicago blues, the electric bass often performs a walking bassline made up of scales and arpeggios. In blues rock bands, the bassist often plays blues scale-based riffs and chugging boogie-style lines. In heavy metal, the bass guitar may perform complex riffs along with the rhythm guitarist or play a low, rumbling pedal point to anchor the group's sound.

A blues bass line played with a pick

The bass guitarist sometimes breaks out of the strict rhythm section role to perform bass breaks or bass solos. The types of bass lines used for bass breaks or bass solos vary by style. In a rock band, a bass break may consist of the bassist playing a riff or lick during a pause in the song. In some styles of metal, a bass break may consist of "shred guitar"-style tapping on the bass. In a funk or funk rock band, a bass solo may showcase the bassist's percussive slap and pop playing. In genres such as progressive rock, art rock, or progressive metal, the bass guitar player may play melody lines along with the lead guitar (or vocalist) and perform extended guitar solos.

Chords are not used that often by electric bass players. However, in some styles, bassists may sound "double stops", such as octaves with open strings and powerchords. In Latin music, double stops with fifths are used.[41]Robert Trujillo of Metallica is known for playing "massive chords" [42] and "chord-based harmonics" [43] on the bass. Lemmy of Motörhead often played power chords in his bass lines.

Solos in metal, funk and progressive rock

While bass guitar solos are not common in popular music, some artists, particularly in the heavy metal, funk, and progressive rock genres, do use them. In a rock context, bass guitar solos are structured and performed in a similar fashion as rock guitar solos, often with the musical accompaniment from the verse or chorus sections.

Bass solos are performed using a range of different techniques, such as plucking or fingerpicking. In the 1960s, The Who's bassist, John Entwistle, performed a bass break on the song "My Generation" using a plectrum. He originally intended to use his fingers, but could not put his plectrum down quickly enough.[citation needed] This is considered as one of the first bass solos in rock music, and also one of the most recognizable. Led Zeppelin's "Good Times Bad Times", the first song on their first album, contains two brief bass solos, occurring after the song's first and third choruses. Queen's bassist, John Deacon, occasionally played bass solos, such as on the song "Liar". Metallica's 1983 debut Kill Em All includes the song "(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth," consisting entirely of a bass solo played by Cliff Burton.

The parody band Spinal Tap performed Big Bottom on their album This Is Spinal Tap, where all three sustaining members played a bass solo, with Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest) credited as "lead bass".

Manowar's bassist Joey DeMaio uses special piccolo bass for his extremely fast bass solos like "Sting of the Bumblebee" and "William's Tale". Green Day bassist Mike Dirnt played a bass solo on the song "Welcome To Paradise" from the 1994 album Dookie and on the song "Makeout Party" from the 2012 album ¡Dos!. U2 includes a bass solo most notably on "Gloria", in which Adam Clayton uses several playing techniques. Matt Freeman of Rancid performs a very fast, guitar-like bass solo in the song "Maxwell Murder". Blink-182's "Voyeur" has a bass solo, which is featured on both their studio album Dude Ranch & their live album The Mark, Tom and Travis Show (The Enema Strikes Back!).

Heavy metal bass players such as Geezer Butler (Black Sabbath), Alex Webster (Cannibal Corpse), Cliff Burton (Metallica), and Les Claypool (Primus, Blind Illusion) have used chime-like harmonics and rapid plucking techniques in their bass solos. Geddy Lee of Rush has made frequent use of bass solos, such as on the instrumental "YYZ". In both published Van Halen concert videos, Michael Anthony performs unique maneuvers and actions during his solos. Funk bassists such as Larry Graham began using slapping and popping techniques for their solos, which coupled a percussive thumb-slapping technique of the lower strings with an aggressive finger-snap of the higher strings, often in rhythmic alternation. The slapping and popping technique incorporates a large number of muted (or 'ghost' tones) to normal notes to add to the rhythmic effect. Slapping and popping solos were prominent in 1980s pop and R&B, and they are still used by some modern funk and Latin bands.

When playing bass solos, rock and metal bassists sometimes use effects such as fuzz bass or a wah-wah pedal to produce a more pronounced sound. Notably, Cliff Burton of Metallica used both effects. Due to the lower range of the bass, bass guitar solos usually have a much lighter accompaniment than solos for other instruments. In some cases, the bass guitar solo is unaccompanied, or accompanied only by the drums.

Jazz and jazz fusion

The electric bass is a relative newcomer to the world of jazz. The big bands of the 1930s and 1940s Swing era and the small combos of the 1950s Bebop and Hard Bop movements all used the double bass. The electric bass was introduced in some bands in the 1950s and it became prominent during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when rock influences were blended with jazz to create jazz-rock fusion.

A walking bass line

The introduction of the electric bass in jazz fusion, as in the rock world, helped bassists play in high-volume stadium concerts with powerful amplifiers, because it is easier to amplify the electric bass than the double bass (the latter is prone to feedback in high-volume settings). The electric bass has both an accompaniment and a soloing role in jazz. In accompaniment, the bassist may perform walking basslines for traditional tunes and jazz standards, playing smooth quarter note lines that imitate the double bass. It is called a walking bass line because of the way it rises and falls using scale notes and passing notes.

For Latin or salsa tunes and rock-infused jazz fusion tunes, the electric bass may play rapid, syncopated rhythmic figures in coordination with the drummer, or lay down a low, heavy groove.

In a jazz setting, the electric bass tends to have a much more expansive solo role than in most popular styles. In most rock settings, the bass guitarist may only have a few short bass breaks or brief solos during a concert. During a jazz concert, a jazz bassist may have a number of lengthy improvised solos, which are called "blowing" in jazz parlance. Whether a jazz bassist is comping (accompanying) or soloing, they usually aim to create a rhythmic drive and "timefeel" that creates a sense of "swing" and "groove". For information on notable jazz bassists, see the List of jazz bassists article.

Use in contemporary classical music

Contemporary classical music uses both the standard instruments of Western Art music (piano, violin, double bass, etc.) and newer instruments or sound producing devices, ranging from electrically amplified instruments to tape players and radios.

The electric bass guitar has occasionally been used in contemporary classical music (art music) since the late 1960s. Contemporary composers often obtained unusual sounds or instrumental timbres through the use of non-traditional (or unconventional) instruments or playing techniques. As such, bass guitarists playing contemporary classical music may be instructed to pluck or strum the instrument in unusual ways.

However, contemporary classical composers may also write for the bass guitar to get its unique sound, and in particular its precise and piercing attack and timbre. For example, Steve Reich, explaining his decision to score 2x5 for two bass guitars, stated that, "[With electric bass guitars] you can have interlocking bass lines, which on an acoustic bass, played pizzicato, would be mud."[44]

Russian and Soviet composer Alfred Schnittke

Composers using electric bass include Christian Wolff (Electric Spring 1, 1966; Electric Spring 2, 1966/70; Electric Spring 3, 1967; and Untitled, 1996); Francis Thorne (Liebesrock 1968–69); Krzysztof Penderecki (Cello Concerto no. 1, 1966/67, rev. 1971/72; Capriccio for Violin and Orchestra, 1967); The Devils of Loudun, 1969; Kosmogonia, 1970; and Partita, 1971); Louis Andriessen (Spektakel, 1970; De Staat, 1972–1976; Hoketus, 1976; De Tijd, 1980–81; and De Materie, 1984–1988); Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen (Symfoni på Rygmarven, 1966; Rerepriser, 1967; and Piece by Piece, 1968); and Irwin Bazelon (Churchill Downs, 1970).

Electric bass has also been used by Leonard Bernstein (MASS, 1971); Dave Brubeck (Truth Has Fallen, 1971); Alfred Schnittke (Symphony No. 1, 1972); and David Amram (En memoria de Chano Pozo, 1977).

In the 1980s and beyond, electric bass was used in works by Hans Werner Henze (El Rey de Harlem, 1980; and Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, 1981), Harold Shapero, On Green Mountain (Chaconne after Monteverdi), 1957, orchestrated 1981; Alfred Schnittke's Symphony No. 3 (1981); Steve Reich's Electric Counterpoint (1987) and 2x5 (2008), Wolfgang Rihm (Die Eroberung von Mexico, 1987–91), Arvo Pärt (Miserere, 1989/92), Steve Martland (Dance works, 1993; and Horses of Instruction, 1994), Sofia Gubaidulina (Aus dem Stundenbuch, 1991), Giya Kancheli (Wingless, 1993), John Adams (I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky, 1995; and Scratchband, 1996/97), Michael Nyman (various works for the Michael Nyman Band), Mark-Anthony Turnage (Blood on the Floor, 1993–1996), numerous works by Art Jarvinen.[45]

Pedagogy and training

The pedagogy and training for the electric bass varies widely by genre and country. Rock and pop bass has a history of pedagogy dating back to the 1950s and 1960s, when method books were developed to help students learn the instrument. One notable method book was Carol Kaye's How to Play the Electric Bass.

In the jazz scene, since the bass guitar takes on much of the same role as the double bass—laying down the rhythm, and outlining the harmonic foundation—electric bass players have long used both bass guitar methods and jazz double bass method books. The use of jazz double bass method books by electric bass players in jazz is facilitated in that jazz methods tend to emphasize improvisation techniques (e.g., how to improvise walking basslines) and rhythmic exercises rather than specific ways of holding or plucking the instrument.

Formal training

Of all of the genres, jazz and the mainstream commercial genres (rock, R&B, etc.) have the most established and comprehensive systems of instruction and training for electric bass. In the jazz scene, teens can begin taking private lessons on the instrument and performing in amateur big bands at high schools or run by the community. Young adults who aspire to be come professional jazz bassists or studio rock bassists can continue their studies in a variety of formal training settings, including colleges and some universities.

Several colleges offer electric bass training in the US. The Bass Institute of Technology (BIT) in Los Angeles was founded in 1978, as part of the Musician's Institute. Chuck Rainey (electric bassist for Aretha Franklin and Marvin Gaye) was BIT's first director. BIT was one of the earliest professional training program for electric bassists. The program teaches a range of modern styles, including funk, rock, jazz, Latin, and R&B.

The Berklee College of Music in Boston offers training for electric bass players. Electric bass students get private lessons and there is a choice of over 270 ensembles to play in. Specific electric bass courses include funk/fusion styles for bass; slap techniques for electric bass; fingerstyle R&B; five- and six-string electric bass playing (including performing chords); and how to read bass sheet music.[46] Berklee College alumni include Jeff Andrews, Victor Bailey, Jeff Berlin, Michael Manring, and Neil Stubenhaus.[46] The Bass Department has two rooms with bass amps for classes and ten private lesson studios equipped with audio recording gear. Berklee offers instruction for the four-, five-, and six-string electric bass, the fretless bass, and double bass. "Students learn concepts in Latin, funk, Motown, and hip-hop, ... jazz, rock, and fusion."[46]

In Canada, the Humber College Institute of Technology & Advanced Learning offers an Advanced Diploma (a three-year program) in jazz and commercial music. The program accepts performers who play bass, guitar, keyboard, drums, melody instruments (e.g., saxophone, flute, violin) and who sing. Students get private lessons and perform in 40 student ensembles.[47]

The Manhattan School of Music, at the intersection of West 122nd Street (Seminary Row) and Broadway

Although there are far fewer university programs that offer electric bass instruction in jazz and popular music, some universities offer bachelor's degrees (B.Mus.) and Master of Music (M.Mus.) degrees in jazz performance or "commercial music", where electric bass can be the main instrument. In the US, the Manhattan School of Music has a jazz program leading to B.Mus. and M.Mus degrees that accepts students who play bass (double bass and electric bass), guitar, piano, drums, and melody instruments (e.g., saxophone, trumpet, etc.).

In the Australian state of Victoria, the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority has set out minimum standards for its electric bass students doing their end-of-year Solo performance recital. To graduate, students must perform pieces and songs from a set list that includes Baroque suite movements that were originally written for cello, 1960s Motown tunes, 1970s fusion jazz solos, and 1980s slap bass tunes. A typical program may include a Prelude by J.S. Bach; "Portrait of Tracy" by Jaco Pastorius; "Twisted" by Wardell Gray and Annie Ross; "What's Going On" by James Jamerson; and the funky Disco hit "Le Freak" by Chic.[48]

In addition to college and university diplomas and degrees, there are a variety of other training programs such as jazz or funk summer camps and festivals, which give students the opportunity to play a wide range of contemporary music, from 1970s-style jazz-rock fusion to 2000s-style R&B.

Informal training

In other less mainstream genres, such as hardcore punk or metal, the pedagogical systems and training sequences are typically not formalized and institutionalized. As such, many players learn by ear, by copying bass lines from records and CDs, and by playing in a number of bands. Even in non-mainstream styles, though, students may be able to take lessons from experts in these or other styles, adapting learned techniques to their own style. As well, there are a range of books, playing methods, and, since the 1990s, instructional DVDs (e.g., how to play metal bass). In the 2010s, many instructional videos are available online on video-sharing websites such as YouTube.

See also

- Guitarrón mexicano

- List of bass guitar manufacturers

Octobass, an extremely large and rare bass instrument from the violin family used in orchestras.- Range

- Washtub bass

Footnotes and references

^ Roberts, Jim (2001). 'How The Fender Bass Changed the World' p. 56 "The surf/instrumental rock genres of the early 1960s were crucial proving grounds of the still-newfangled electric bass ..."

^ "Audiovox #736: The World's First Electric Bass Guitar!". Vintage Guitar. June 19, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ How the Fender Bass Change The World, BackBeat Books, 2001

ISBN 0-87930-630-0, page 28/29

^ "Audiovox and Serenader Amps". Vintageguitar.com. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

^ ab Slog, John J.; Coryat, Karl [ed.] (1999). The Bass Player Book: Equipment, Technique, Styles and Artists. Backbeat Books. p. 154.

ISBN 0-87930-573-8

^ Book review of How The Fender Bass Changed The World. Available online at: http://blogcritics.org/books/article/how-the-fender-bass-changed-the/ Archived November 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

^ George, Nelson (1998). Hip Hop America. Viking Press. p. 91.

ISBN 978-0-670-87153-7

^ Interview with Chuck Rainey, Bass Heroes, ed. Tom Mulhern, 1993, pp165.

^ ab Bacon, Tony (2000). 50 Years of Fender. Backbeat Books. p. 24.

ISBN 0-87930-621-1

^ H.), Roberts, Jim (James (2001). How the Fender bass changed the world. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-630-0. OCLC 46319707.

^ "Gibson EB-1偺晹壆". Retrieved March 29, 2015.