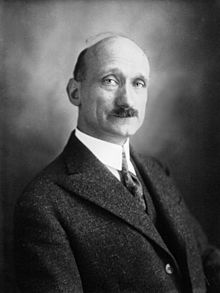

Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of France | |

In office 24 November 1947 – 26 July 1948 | |

| President | Vincent Auriol |

| Preceded by | Paul Ramadier |

| Succeeded by | André Marie |

In office 5 September 1948 – 11 September 1948 | |

| President | Vincent Auriol |

| Preceded by | André Marie |

| Succeeded by | Henri Queuille |

| President of the European Parliament | |

In office 19 March 1958 – 18 March 1960 | |

| Preceded by | Hans Furler |

| Succeeded by | Hans Furler |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Robert Schuman 29 June 1886 Luxembourg City, Luxembourg |

| Died | 4 September 1963(1963-09-04) (aged 77) Scy-Chazelles, Lorraine, France |

| Political party | Popular Republican Movement |

Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Robert Schuman (French: [ʁɔbɛʁ ʃuman]; 29 June 1886 – 4 September 1963) was a Luxembourg-born French statesman. Schuman was a Christian Democrat (MRP) and an independent political thinker and activist. Twice Prime Minister of France, a reformist Minister of Finance and a Foreign Minister, he was instrumental in building post-war European and trans-Atlantic institutions and was one of the founders of the European Union, the Council of Europe and NATO.[1] The 1964–1965 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honour.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Inter-war period

3 World War II

4 French minister

5 European politics

6 Memorials

7 Governments

7.1 First ministry (24 November 1947 – 26 July 1948)

7.2 Second ministry (5–11 September 1948)

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Early life

Robert Schuman's birthplace in Clausen, a suburb of Luxembourg City

Schuman was born in June 1886, in Clausen, Luxembourg, having his father's then German nationality. His father, Jean-Pierre Schuman (d.1900), who was a native of Lorraine and was born a Frenchman, became German when Lorraine was annexed by Germany in 1871, before he left to settle in Luxembourg, not far from his native village of Evrange. Schuman's mother (d. 1911) was a Luxembourger. Schuman's secondary schooling from 1896 to 1903 was at Athénée de Luxembourg, followed in 1904 by the Lycée impérial in Metz. From 1904 to 1910 he studied law, economics, political philosophy, theology and statistics at the Universities of Berlin, Munich, Bonn and Strasbourg, and received a law degree with the highest distinction from Strasbourg University.[2] In 1912 Schuman set up practice as a lawyer in Metz. When war broke out in 1914 he was called up for the auxiliary troops by the German army in Metz but excused from military service on health grounds. From 1915 to 1918 he served in the administration of the Boulay district.[3]

Inter-war period

Portrait of Robert Schuman, député from Moselle (1929).

After the First World War, Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France and Schuman became a French citizen in 1919.

Schuman became active in French politics. In 1919 he was first elected as député to parliament on a regional list, and later serving as the député for Thionville (Moselle) until 1958 with an interval during the war years. He made a major contribution to the drafting and parliamentary passage of the reintroduction of the French Civil and Commercial codes by the French parliament, after that the Alsace-Lorraine region, until there under the German domain (and the German law) came back to France. This harmonization of the regional law with the French law was called "Lex Schuman".[4] Schuman also investigated and patiently uncovered postwar corruption in the Lorraine steel industries and in the Alsace and Lorraine railways, both bought by a derisory price by the powerful and influential de Wendel family, what he called in the Parliament "a pillage".[5]

World War II

In 1940, because of his expertise on Germany, Schuman was called to become a member of Paul Reynaud's wartime government, in charge of the refugees. He kept that charge during the first Pétain government. On 10 July, he voted to give full power to Hitler's ally Marshal Pétain, but refused to continue to be in the government. Later that year, on 14 September, he was arrested for acts of resistance and protest against Nazi methods. He was interrogated by the Gestapo but thanks to the intervention of a German lawyer, he was saved from being sent to Dachau. Transferred as a personal prisoner of Gauleiter Joseph Buerckel, he escaped in 1942 and re-joined the French Resistance.[citation needed] He addressed large conferences in the Free Zone explaining why the defeat of Germany was inevitable.[citation needed] This was at a time when Nazi Germany was at the peak of its power. The Germans then invaded the Free Zone. Although his life was still at risk, he spoke to friends about a Franco-German and European reconciliation that must take place after the end of hostilities, as he had already done in 1939–40.[citation needed]

French minister

Schuman at the French embassy in Washington, after the signature of the treaty that created NATO, in April 1949.

After the war, Schuman rose to great prominence. He initially had difficulties because of his 1940 vote and his tenure as Pétain's minister. The Defence minister Andre Diethelm stated that "this Vichy product should be immediately kicked out", as all those who had voted for Pétain, should be ineligible.[clarification needed] He was stricken with "Indignité nationale". On 24 July 1945, Schuman wrote to General de Gaulle to ask him to intervene. De Gaulle answered favorably, and on 15 September, Schuman regained his full civic rights,[6] becoming able to again play an active role in French politics. He was Minister of Finance, then Prime Minister from 1947–1948, assuring parliamentary stability during a period of revolutionary strikes and attempted insurrection. In the last days of his first administration, his government proposed plans that later resulted in the Council of Europe and the European Community single market.[7] Becoming Foreign Minister in 1948, he retained the post in different governments until early 1953. When Schuman's first government had proposed the creation of a European Assembly, it made the issue a governmental matter for Europe, not merely an academic discussion or the subject of private conferences, like The Hague Congress of the European Movements earlier that year. (Schuman's was one of the few governments to send active ministers.) This proposal saw life as the Council of Europe and was created within the tight schedule Schuman had set. At the signing of its Statutes at St James's Palace, London, 5 May 1949, the founding States agreed to defining the frontiers of Europe based on the principles of human rights and fundamental freedoms that Schuman enunciated there. He also announced a coming supranational union for Europe that saw light as the European Coal and Steel Community and other such Communities within a Union framework of common law and democracy.

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

We are carrying out a great experiment, the fulfillment of the same recurrent dream that for ten centuries has revisited the peoples of Europe: creating between them an organization putting an end to war and guaranteeing an eternal peace. The Roman church of the Middle Ages failed finally in its attempts that were inspired by humane and human preoccupations. Another idea, that of a world empire constituted under the auspices of German emperors was less disinterested; it already relied on the unacceptable pretensions of a ‘Führertum’ (domination by dictatorship) whose 'charms' we have all experienced.

Audacious minds, such as Dante, Erasmus, Abbé de St-Pierre, Rousseau, Kant and Proudhon, had created in the abstract the framework for systems that were both ingenious and generous. The title of one of these systems became the synonym of all that is impractical: Utopia, itself a work of genius, written by Thomas More, the Chancellor of Henry VIII, King of England.

The European spirit signifies being conscious of belonging to a cultural family and to have a willingness to serve that community in the spirit of total mutuality, without any hidden motives of hegemony or the selfish exploitation of others. The 19th century saw feudal ideas being opposed and, with the rise of a national spirit, nationalities asserting themselves. Our century, that has witnessed the catastrophes resulting in the unending clash of nationalities and nationalisms, must attempt and succeed in reconciling nations in a supranational association. This would safeguard the diversities and aspirations of each nation while coordinating them in the same manner as the regions are coordinated within the unity of the nation.

— Robert Schuman, speaking in Strasbourg, 16 May 1949[8]

As Foreign Minister, he announced in September 1948 and the following year before the United Nations General Assembly, France's aim to create a democratic organisation for Europe which a post-Nazi and democratic Germany could join.[9] In 1949–50, he made a series of speeches in Europe and North America about creating a supranational European Community.[8] This supranational structure, he said, would create lasting peace between Member States.

Our hope is that Germany will commit itself on a road that will allow it to find again its place in the community of free nations, commencing with that European Community of which the Council of Europe is a herald.

— Robert Schuman, speaking at the United Nations, 23 September 1949[9]

On 9 May 1950, these principles of supranational democracy were announced in what has become known as the Schuman Declaration.[10] The text was jointly prepared by Paul Reuter, the legal adviser at the Foreign Ministry, his chef-de Cabinet, Bernard Clappier and Jean Monnet and two of his team, Pierre Uri and Etienne Hirsch. The French Government agreed to the Schuman Declaration which invited the Germans and all other European countries to manage their coal and steel industries jointly and democratically in Europe's first supranational Community with its five foundational institutions. On 18 April 1951 six founder members signed the Treaty of Paris (1951) that formed the basis of the European Coal and Steel Community. They declared this date and the corresponding democratic, supranational principles to be the 'real foundation of Europe'. Three Communities have been created so far. The Treaties of Rome, 1957, created the Economic community and the nuclear non-proliferation Community, Euratom. Together with intergovernmental machinery of later treaties, these eventually evolved into the European Union. The Schuman Declaration, was made on 9 May 1950 and to this day 9 May is designated Europe Day.

As Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Schuman was instrumental in the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Schuman also signed the Treaty of Washington (1949) for France. The defensive principles of NATO's Article 5 were also repeated in the European Defence Community Treaty which failed as the French National Assembly declined to vote its ratification. Schuman was a proponent of an Atlantic Community.

European politics

On 19 March 1958, the first meeting of the European Parliamentary Assembly was held in Strasbourg under the Presidency of Robert Schuman.

Schuman later served as Minister of Justice before becoming the first President of the European Parliamentary Assembly (the successor to the Common Assembly) which bestowed on him by acclamation the title 'Father of Europe'. He is considered one of the founding fathers of the European Union. He presided over the European Movement from 1955 to 1961. In 1958 he received the Karlspreis,[11] an Award by the German city of Aachen to people who contributed to the European idea and European peace, commemorating Charlemagne, ruler of what is today France and Germany, who resided in and is buried at Aachen. Schuman was also made a knight of the Order of Pius IX.[12]

Schuman was an intensely religious man and a Bible scholar.[13] He commended the writings of Pope Pius XII who condemned both fascism and communism. He was an expert in medieval philosophy,[13] especially the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas,[14] and he thought highly of the philosopher Jacques Maritain, a contemporary.[15]

Memorials

Grave of Robert Schuman in Saint Quentin church, in Scy-Chazelles, near Metz, France

The monument "Homage to the Founding Fathers of Europe" in front of Schuman's house in Scy-Chazelles by Russian artist Zurab Tsereteli, unveiled October 20, 2012. The statues represent the four founders of Europe - Alcide de Gasperi, Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet and Konrad Adenauer.

The Schuman District of Brussels (including a metro/railway station and a tunnel, as well as a square) is named in his honour. Around the square ("Schuman roundabout") can be found various European institutions, including the Berlaymont building which is the headquarters of the European Commission and has a monument to Schuman outside, as well as key European Parliament buildings. In the nearby Cinquantenaire Park, there is a bust of Schuman as a memorial to him. The European Parliament awards the Robert Schuman Scholarship[16] for university graduates to complete a traineeship within the European Parliament and gain experience within the different committees, legislative processes and framework of the European Union.

A Social Science University named after him lies in Strasbourg (France) along with the Avenue du President Robert Schuman in that city's European Quarter. In Luxembourg there is a Rond Point Schuman,[17]Boulevard Robert Schuman, a school called Lycée Robert Schuman and a Robert Schuman Building, of the European Parliament. In Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg, there is a Rue Robert Schuman.[18] The house where he was born was restored by the European Parliament and can be visited, as can his home in Scy-Chazelles just outside Metz.

In Aix-en-Provence, a town in Bouches-du-Rhone, France, there is an Avenue Robert Schumann, which houses the three university buildings of the town and in Ireland there is a building in the University of Limerick named the "Robert Schuman" building.

The European University Institute in Florence, Italy, is home to the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), focusing on "inter-disciplinary, comparative, and policy research on the major issues on the European integration process".[19]

The Robert Schuman Institute in Budapest, Hungary, a European level training institution of the European People's Party family is dedicated to promoting the idea of a united Europe, supporting and the process of democratic transformation in Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe and the development of Christian Democratic and centre right political parties also bears the name of Robert Schuman.

In 1965, the Robert Schuman Mittelschule in the St. Mang suburb of the city of Kempten in southern Bavaria was named after him.[20]

Governments

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

Organizations

|

Ideas

|

Documents

|

People

|

|

First ministry (24 November 1947 – 26 July 1948)

- Robert Schuman – President of the Council

Georges Bidault – Minister of Foreign Affairs

Pierre-Henri Teitgen – Minister of National Defense

Jules Moch – Minister of the Interior

René Mayer – Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs

Robert Lacoste – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Daniel Mayer – Minister of Labour and Social Security

André Marie – Minister of Justice

Marcel Edmond Naegelen – Minister of National Education

François Mitterrand – Minister of Veterans and War Victims

Pierre Pflimlin – Minister of Agriculture

Paul Coste-Floret – Minister of Overseas France

Christian Pineau – Minister of Public Works and Transport

Germaine Poinso-Chapuis – Minister of Public Health and Population

René Coty – Minister of Reconstruction and Town Planning

Changes:

- 12 February 1948 – Édouard Depreux succeeds Naegelen as Minister of National Education.

Second ministry (5–11 September 1948)

- Robert Schuman – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

René Mayer – Minister of National Defense

André Marie – Vice President of the Council

Jules Moch – Minister of the Interior

Christian Pineau – Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs

Robert Lacoste – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Daniel Mayer – Minister of Labour and Social Security

Robert Lecourt – Minister of Justice

Tony Revillon – Minister of National Education

Jules Catoire – Minister of Veterans and War Victims

Pierre Pflimlin – Minister of Agriculture

Paul Coste-Floret – Minister of Overseas France

Henri Queuille – Minister of Public Works, Transport, and Tourism

Pierre Schneiter – Minister of Public Health and Population

René Coty – Minister of Reconstruction and Town Planning

See also

References

^ "Key dates in Schuman's life". Schuman.info. Retrieved 3 November 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Anonymous (16 June 2016). "About the EU - European Union - European Commission" (PDF). European Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2016.

^ "Biography - Robert Schuman centre - CERS". www.centre-robert-schuman.org. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

^ "Conférence à l'occasion du 60e anniversaire de la Déclaration Schuman : Fondation d'une gouvernance en Europe – Europaforum Luxembourg". www.europaforum.public.lu. May 2010. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

^ Lejeune, René (2000). Robert Schuman, père de l'Europe. Paris: Fayard. p. 98. ISBN 9782213606354.

^ Poitevin, Raymond. "Robert Schuman : un itinéraire étonnant Par Raymond Poidevin". Fondation Robert Schuman. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

^ "Schuman and the Hague conferences". Schuman.info. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

^ ab "Schuman's speech at Strasbourg, announcing the coming supranational European Community". Schuman.info. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

^ ab "Schuman's speeches at the UN 1948 and 1949". Schuman.info. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

^ "Full text of Schuman Declaration". Schuman.info. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

^ "Charlemagne Prize Laureate 1958 Robert Schuman". Der Internationale Karlspreis zu Aachen (International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

^ "Robert Schuman And May 9th". European Parliamentary Research Service. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

^ ab Wilton, Gary (2016). "Chapter 1: Christianity at the founding: the legacy of Robert Schuman". In Chaplin, Johnathan; Wilton, Gary. God and the EU: Faith in the European Project. Routledge. pp. 13–32. ISBN 978-1-138-90863-5.

^ Fimister, Alan (2008). Robert Schuman: Neo Scholastic Humanism and the Reunification of Europe. P.I.E Peter Lang. p. 198. ISBN 978-90-5201-439-5.

^ Pour l'Europe (For Europe) Paris 1963

^ "Traineeships". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

^ "Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies". European University Institute. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

^ "Homepage der Robert-Schuman-Mittelschule Sankt Mang". Retrieved 2015-12-24.

Further reading

- Fimister, Alan. Robert Schuman: Neo-Scholastic Humanism and the Reunification of Europe (2008)

Kaiser, Wolfram. "From state to society? The historiography of European integration." in Michelle Cini, and Angela K. Bourne, eds. Palgrave Advances in European Union Studies (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2006). pp. 190–208.- Schuman, Robert. "France and Europe." Foreign Affairs 31.3 (1953): 349–60.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Schuman. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Schuman Declaration |

Schuman Project, biographical information plus analysis of Schuman's work initiating a supranational European Community, why it is a major political innovation, and its comparison with classical federalism. Site includes some of Schuman's key speeches announcing the innovation in 1949–50.- Fondation Robert Schuman

The Katholische Akademie Trier is vested in the Robert Schuman-Haus (in German)

Schuman Declaration (9 May 1950) (in English) (in German) (in Spanish) (in French)

Video of the Schuman Declaration of the creation of the ECSC – European Navigator

1949 letter from the UK Foreign minister Ernest Bevin to Robert Schuman, urging a reconsideration of the industrial dismantling policy in Germany.

Literature by and about Robert Schuman in the German National Library catalogue

Works by and about Robert Schuman in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

Robert Schuman in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

Newspaper clippings about Robert Schuman in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)- Robert Schuman archives at the "Fondation Jean Monnet"

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Paul Ramadier | Prime Minister of France 1947–1948 | Succeeded by André Marie |

| Preceded by Georges Bidault | French Minister of Foreign Affairs 1948–1953 | Succeeded by Georges Bidault |

| Preceded by André Marie | Prime Minister of France 1948 | Succeeded by Henri Queuille |

| Preceded by Emmanuel Temple | French Minister of Justice 1955–1956 | Succeeded by François Mitterrand |