Cheval de frise

Chevaux de frise at the Confederate Fort Mahone defenses at Siege of Petersburg

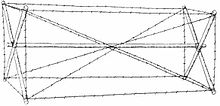

The cheval de frise (plural: chevaux de frise [ʃə.vo də fʁiz], "Frisian horses") was a medieval defensive anti-cavalry measure consisting of a portable frame (sometimes just a simple log) covered with many projecting long iron or wooden spikes or spears.[1] They were principally intended as an anti-cavalry obstacle but could also be moved quickly to help block a breach in another barrier. They remained in occasional use until they were replaced by wire obstacles just after the American Civil War. During the Civil War, the Confederates used this type of barrier more often than the Union forces.[2] During World War I, armies used chevaux de frise to temporarily plug gaps in barbed wire.[3][4] Barbed wire chevaux de frise were used in jungle fighting on south Pacific islands during World War II.

The term is also applied to defensive works comprising a series of closely set upright stones found outside the ramparts of Iron Age hillforts in northern Europe.[5]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 Use

3 Legacy

4 References

Etymology

Chevaux de frise, according to the later use of the term, could include broken glass studding the top of a wall in a nineteenth-century fort

In French, cheval de frise literally means "Frisian horse".[6][7] The Frisians, having few cavalry, relied heavily on such anti-cavalry obstacles in warfare. The Dutch also adopted use of the defensive device when at war with Spain. The term came to be used for any spiked obstacle, such as broken glass embedded in mortar on the top of a wall.

The cheval de frise was adapted in New York and Pennsylvania during the American Revolutionary War as a defensive measure installed in rivers to prevent upriver movement by enemy ships.

Use

Hessian map showing the placement of chevaux de frise in the Delaware River in 1777.

During the American Revolutionary War, Robert Erskine designed an anti-ship version of the cheval-de-frise to prevent British warships from proceeding up the Hudson River. A cheval-de-frise was placed between Fort Washington at northern Manhattan and Fort Lee in New Jersey in 1776. The following year construction began on another one to the north of West Point at Pollepel Island, but it was overshadowed by completion of The Great Chain across the Hudson in 1778, which was used through 1782.

Similar devices planned by Ben Franklin and designed by Robert Smith[8][9] were used in the Delaware River near Philadelphia, between Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer.[10] Two other lines of chevaux-de-frise were also placed across the Delaware River at Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania and Fort Billingsport, New Jersey as a first line of defense for Philadelphia against the British naval forces.[11]

A cheval-de-frise was retrieved from the Delaware River in Philadelphia on November 13, 2007 in excellent condition, after more than two centuries in the river.[12] In November 2012, a 29-foot (9 m) spike from a cheval-de-frise was recovered from the Delaware off Bristol Township; it was also believed to be from the Revolutionary era installation at Philadelphia and freed up by Hurricane Sandy earlier that fall.[13]

The "knife rest" or "Spanish rider" is a modern wire obstacle functionally similar to the cheval de frise, and sometimes called that.

Legacy

A small promontory on the north-east Essex coast in the United Kingdom (UK), between Holland Haven and Frinton-on-Sea, was named Chevaux de Frise Point.

References

^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 114..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 114..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Mahan, Peter, Chevaux-de-frise, NPS.

^ Thomas Boyd (1923). Through the Wheat. University of Nebraska Press, 2000. p. 226. ISBN 0-8032-6168-3.

^ https://web.archive.org/web/20080517184133/http://www.1914-1918.net/Diaries/wardiary-2msex.htm

^ Timothy Darvill (2002). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953404-3.

^ Chevaux de Frise, Charleston footprints, 2011-02-24.

^ Friesian horse.

^ Robert Smith at Find a grave

^ Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. pp. 505–506. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

^ Lossing, "III", Field Book of the Revolution, II, Roots web.

^ "The Plank House". www.marcushookps.org. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

^ "Revolutionary War Artifact from the Depths of the Delaware River". Independence Seaport Museum. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

^ Elizabeth Fisher, "SANDY STIRS UP HISTORY: Revolutionary War spike pulled from the river depths in Bristol", Bristol Pilot, 21 November 2012, accessed 15 May 2014