Valle Crucis Abbey

| Valle Crucis Abbey | |

|---|---|

Valle Crucis Abbey (2008) | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Llantysilio, Denbighshire, Wales |

| Geographic coordinates | 52°59′21″N 3°11′14″W / 52.98918°N 3.187142°W / 52.98918; -3.187142Coordinates: 52°59′21″N 3°11′14″W / 52.98918°N 3.187142°W / 52.98918; -3.187142 |

| Affiliation | Catholicism, Cistercians |

| Year consecrated | pre 1236 |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Ruins. Abbey dissolved 1537. |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | unknown |

| Architectural type | Monastery |

| Architectural style | Cistercian |

| Groundbreaking | 1201 |

Valle Crucis Abbey (Valley of the Cross) is a Cistercian abbey located in Llantysilio in Denbighshire, Wales. More formally the Abbey Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Valle Crucis it is known in Welsh both as Abaty Glyn Egwestl and Abaty Glyn y Groes.

The abbey was built in 1201 by Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor, Prince of Powys Fadog. Valle Crucis was dissolved in 1537 during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and subsequently fell into serious disrepair. The building is now a ruin, though large parts of the original structure still survive. Valle Crucis Abbey is now under the care of Cadw.

Contents

1 History

2 Architectural layout

3 Gallery

4 See also

5 References

6 Notes

7 External links

History

Valle Crucis Abbey was founded in 1201 by Madog ap Gruffydd Maelor,[1] on the site of a temporary wooden church[2] and was the last Cistercian monastery to be built in Wales. Founded in the principality of Powys Fadog, Valle Crucis was the spiritual centre of the region, while Dinas Bran was the political stronghold.[3] The abbey took its name from the nearby Pillar of Eliseg, which was erected four centuries earlier by Cyngen ap Cadell, King of Powys in memory of his great-grandfather, Elisedd ap Gwylog.[4]

Madog was buried in the then-completed abbey upon his death in 1236. Not long after Madog's death, it is believed that a serious fire badly damaged the abbey, with archaeological evidence that the church and south range were affected.

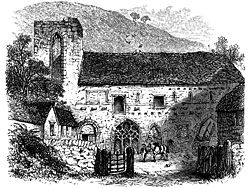

1875 drawing of the abbey by Alfred Rimmer

The chapterhouse in the east range; compare to the drawing by Rimmer over a century earlier

The location on which Valle Crucis was raised was originally established as a colony of twelve monks[2] from Strata Marcella,[4] an earlier abbey located on the western bank of the River Severn near Welshpool.[5] The original wooden structure was replaced with stone structures of roughly faced rubble.[2] The completed abbey is believed to have housed up to about sixty brethren, 20 choir monks and 40 lay-members who would have carried out the day-to-day duties including agricultural work. The numbers within the church fluctuated throughout its history and the monks and the abbey itself came under threat from various political and religious events. The abbey is believed to have been involved in the Welsh Wars of Edward I of England during the 13th century, and was supposedly damaged in the uprising led by Owain Glyndŵr. Numbers also fell after the Black Death ravaged Britain.

The fortunes of Valle Crucis improved during the 15th century, and the abbey gained a reputation as a place of hospitality. Several important Welsh poets of the period spent time at the abbey including Gutun Owain, Tudur Aled and Guto'r Glyn.[4] Guto'r Glyn spent the last few years of his life at the abbey, and was buried at the site in 1493.[6]

In 1537, Valle Crucis was dissolved, as it was deemed not prosperous compared to the more wealthy English abbeys. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the site fell into disrepair, and the building was given to Sir William Puckering on a 21-year lease by Henry VIII. The lease was renewed under the reign of Henry's son Edward VI in 1551, but after Sir William's death in 1574, the property was passed to his daughter, Hestor. In 1575 Hestor married Edward Wotton, 1st Baron Wotton,[7] and the lease was extended to Baron Wotton in 1583 by Elizabeth I. By the late 16th century the eastern range was converted into a manor house. Valle Crucis remained with the Wotton family, and was inherited by the 2nd Baron Wotton, but upon his death it was passed to Hestor Wotton, his third daughter. Hestor married Baptist Noel, 3rd Viscount Campden and the abbey entered the family's ownership, before being sold shortly afterwards when the estate was sequestered by Parliament in 1651.[8] By the late 18th century the building that remained were re-roofed and the site was used as a farm, before excavations were undertaken in the later half of the 19th century. The site is now cared for by Cadw, and is an open visitor attraction. It is surrounded by a caravan park, which occupies fields on three sides and extends up to the outer walls of the ruin.[9]

Architectural layout

Engraving taken from Hone's Table-book, showing Pillar of Eliseg with the west front wall of Crucis Abbey in the background

Valle Crucis Abbey consisted of the church plus several adjoining out buildings which enclosed a square courtyard. The church itself ran West to East in the traditional cruciform style. Today much of the original church is ruined, though the west end front wall survives, including the masonry of the rose window, and much of the east end. In the 14th century the church was effectively divided by a pulpitum across the nave. The lay brothers worshipped before an altar in front of the pulpitum, and the choir monks before the high altar or side chapels.

The outbuildings including the adjoining east range, which survives mainly intact and the west range, which housed the lay brethren’s frater, but is now demolished. Completing the four sides of the inner courtyard was the southern frater and kitchen, which faced the church; these two building are also now ruins, with only foundation stones remaining. The east and west ranges housed the cloisters, with the east range also leading to the final structure, the abbot's lodgings which settled between the range and the church but outside the courtyard. The site is also home to the only remaining monastic fishpond in Wales,[4][10] but suffered from being remodelled as a reflecting pool in the 18th century.[2]

As well as the west end front wall, extensive parts of the east end of the structures survive to the present day. The chancel walls, the southern part of the transept, the east range of the cloister together with the chapter house and sacristy and the lower part of the reredorter all survive mainly intact.[2] In 1870 the west end wall was restored by George Gilbert Scott.[2] Rather unusually for a monastic ruin, parts of the first floor can be accessed, including the dormitory and abbot's lodgings.

Many pieces have been removed by the local museum, and the font from the church was placed in the gardens of Plas Newydd, Llangollen by the Ladies of Llangollen in the late 18th century.

Gallery

Panorama of Valle Crucis Abbey

Chapter House vaulting

Detail of corbelling

Detail of tracery

Abbey church interior - West End

Abbey church interior - South Transept. Part of pulpitum at the centre.

Stairs at side of late medieval pulpitum.

See also

- List of abbeys and priories in Wales

- List of Cadw properties

References

Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Jenkins, Simon (2008). Wales - Churches, Houses, Castles. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-713-99893-1.

Notes

^ Davies (2008), pg528.

^ abcdef Evans D.H. (2008-11-10). "Valle Crucis Abbey". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

^ Davies (2008), pg705.

^ abcd Davies (2008), pg509.

^ Davies (2008), pg945.

^ Davies (2008), pg341.

^ Hester Puckering life profile The Peerage

^ The Noel family and its estates nationalarchives.gov.uk

^ Jenkins (2008), pg85.

^ "Valle Crucis Abbey, Llangollen, North Wales". The Heritage Trail. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Valle Crucis Abbey. |

Valle Crucis Abbey Visitor website Cadw