Tintern Abbey

| |

Tintern Abbey shown within Wales | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Cistercian |

| Established | 1131 |

| Disestablished | 1536 |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Walter de Clare |

| Site | |

| Location | Tintern, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Coordinates | 51°41′49″N 2°40′37″W / 51.697°N 2.677°W / 51.697; -2.677Coordinates: 51°41′49″N 2°40′37″W / 51.697°N 2.677°W / 51.697; -2.677 |

Tintern Abbey (Welsh: Abaty Tyndyrn ![]() pronunciation (help·info)) was founded by Walter de Clare, Lord of Chepstow, on 9 May 1131. It is situated adjacent to the village of Tintern in Monmouthshire, on the Welsh bank of the River Wye, which at this point forms the border between Monmouthshire in Wales and Gloucestershire in England. It was only the second Cistercian foundation in Britain (after Waverley Abbey), and the first in Wales. The abbey fell into ruin after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century. Its remains have been celebrated in poetry and painting from the 18th century onwards. In 1984 Cadw took over responsibility for the site. The site welcomes approximately 70,000 people every year.[1]

pronunciation (help·info)) was founded by Walter de Clare, Lord of Chepstow, on 9 May 1131. It is situated adjacent to the village of Tintern in Monmouthshire, on the Welsh bank of the River Wye, which at this point forms the border between Monmouthshire in Wales and Gloucestershire in England. It was only the second Cistercian foundation in Britain (after Waverley Abbey), and the first in Wales. The abbey fell into ruin after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century. Its remains have been celebrated in poetry and painting from the 18th century onwards. In 1984 Cadw took over responsibility for the site. The site welcomes approximately 70,000 people every year.[1]

Contents

1 Foundation

2 Development of the buildings

3 Abbots

4 Dissolution and ruin

5 Poetry and painting

6 Industry and access

7 Heritage

8 Burials

9 Gallery

10 References

11 External links

Foundation

Walter de Clare, of the powerful family of Clare, was first cousin of William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, who had introduced the first colony of Cistercians to Waverley, Surrey, in 1128. The monks for Tintern came from a daughter house of Cîteaux, L'Aumône Abbey, in the diocese of Chartres in France.[2] In time, Tintern established two daughter houses, Kingswood in Gloucestershire (1139) and Tintern Parva, west of Wexford in southeast Ireland (1203).

The Cistercian monks (or White Monks) who lived at Tintern followed the Rule of Saint Benedict. The Carta Caritatis (Charter of Love) laid out their basic principles, of obedience, poverty, chastity, silence, prayer, and work. With this austere way of life, the Cistercians were one of the most successful orders in the 12th and 13th centuries. The lands of the Abbey were divided into agricultural units or granges, on which local people worked and provided services such as smithies to the Abbey. Many endowments of land on both sides of the Wye were made to the Abbey.

Development of the buildings

The present-day remains of Tintern are a mixture of building works covering a 400-year period between 1136 and 1536. Very little remains of the first buildings; a few sections of walling are incorporated into later buildings and the two recessed cupboards for books on the east of the cloisters are from this period. The church of that time was smaller than the present building and was slightly to the north.

Tintern Abbey, interior

During the 13th century the Abbey was mostly rebuilt; first the cloisters and the domestic ranges, then finally the great church between 1269 and 1301. The first mass in the rebuilt presbytery was recorded to have taken place in 1288, and the building was consecrated in 1301, although building work continued for several decades.[3]Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, the then lord of Chepstow, was a generous benefactor; his monumental undertaking was the rebuilding of the church. The Abbey put his coat of arms in the glass of its east window in thanks to him.

It is this great abbey church that is seen today. It has a cruciform plan with an aisled nave; two chapels in each transept and a square ended aisled chancel. The Decorated Gothic church represents the architectural developments of its day. The abbey is built of Old Red Sandstone, of colours varying from purple to buff and grey. Its total length from east to west is 228 feet, while the transept is 150 feet in length.[4]

In 1326 King Edward II stayed at Tintern for two nights. In 1349 the Black Death swept the country and it became impossible to attract new recruits for the lay brotherhood. Changes to the way the granges were tenanted out rather than worked by lay brothers show that Tintern was short of labour. In the early 15th century Tintern was short of money, due in part to the effects of the Welsh uprising under Owain Glyndŵr against the English kings, when Abbey properties were destroyed by the Welsh rebels. The closest battle to the abbey was at Craig-y-dorth near Monmouth, between Trellech and Mitchel Troy.

Abbots

| Name | Appointment | Transferred or died | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| William[5] | c. 1139 | 1148 | |

| Henry | before 1153 | transferred to Waverley c. 1161 | Henry was a former robber who repented of his ways,[6] took the Cistercian habit and was duly appointed abbot of Tintern where he was renowned for his profusion of tears at the altar. |

| William II | before 1169 | 1188 | |

| Eudo | 1188 | Eudo previously served as prior of Waverley and abbot of Kingswood | |

| Richard[7] | before 1218[8] | ||

| Ralph | 1232 | 1245 | Translated to Dunkeswell |

| "J" | c. 1253 | ||

| Vacancy | 1259 | ||

| John | before 1267 | 1277 | |

| Ralph | c. 1285 | 1303 | |

| Hugh de Wyke | 1305 | 1320 | buried at the Cistercian abbey of Stratford Langthorne |

| Walter of Hereford | 1321 | 1331 | |

| Roger de Camme | 1330 | 1331 | |

| Walter | c. 1333 | ||

| Gilbert | 1340 | 1341 | |

| John | c. 1349 | 1375 | |

| John Wysbech | 1387 | 1407 | previously abbot of Grace Dieu |

| John | fl. 1411 | ||

| John Chernyllis, Cherville | 1421 | appointed papal chaplain in May 1413 | |

| John Chapfeld | 1437 | ||

| Robert Acton | 1438 | 1441 | |

| John Tynyern | 1442 | 1455 | |

| Thomas Monmouth | 1456 | c. 1459 | |

| Thomas Colston | 1460 | 1486 | |

| William Ker | c. 1488 | 1492 | |

| Harry Newland | 1493 | 1506 | |

| Thomas Morton | fl. 1514 | ||

| Richard Wych | 1536[9] | awarded a pension following the dissolution |

Dissolution and ruin

The Chancel and Crossing of Tintern Abbey, Looking towards the East Window by J. M. W. Turner, 1794

In the reign of King Henry VIII, his Dissolution of the Monasteries ended monastic life in England, Wales and Ireland. On 3 September 1536, Abbot Wych surrendered Tintern Abbey and all its estates to the King's visitors and ended a way of life that had lasted 400 years. Valuables from the Abbey were sent to the royal Treasury and Abbot Wych was pensioned off. The building was granted to the then lord of Chepstow, Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester. Lead from the roof was sold and the decay of the buildings began.

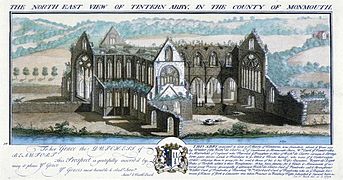

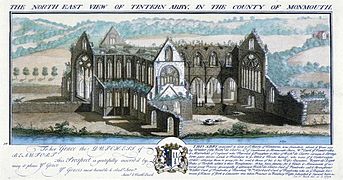

In the next two centuries little or no interest was shown in the history of the site. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the ruins were inhabited by workers in the local wire works.[3] However, in the mid-18th century it became fashionable to visit "wilder" parts of the country. The Wye Valley in particular was well known for its romantic and picturesque qualities and the ivy clad Abbey became frequented by tourists. One of the earliest prints of the Abbey was in the series of engravings of historical sites made in 1732 by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck.[10] After the publication of the book Observations on the River Wye by the Reverend William Gilpin following his 1770 tour,[11] visitors greatly increased, a fact evidenced both by the number of poetic descriptions and of atmospheric paintings and prints of the site.

Poetry and painting

A dedicatory letter at the start of Gilpin’s work is addressed to the poet William Mason and mentions a similar tour made in 1771 by the poet Thomas Gray. Neither of those dedicated a poem to the Abbey, but it appeared in the work of a number of others, including Rev. Dr. Syned Davies’ long “Describing a Voyage to Tintern Abbey, in Monmouthshire, from Whitminster in Gloucestershire”, which was made by boat with a party of others as early as 1745.[12] Another topographical work, the six-canto Chepstow; or, A new guide to gentlemen and ladies whose curiosity leads them to visit Chepstow: Piercefield-walks, Tintern-abbey, and the beautiful romantic banks of the Wye, from Tintern to Chepstow by water, was published from Bristol in 1786.[13] There was also the “Poetical description of Tintern Abbey” by the parson poet Rev. Duncomb Davis, who lived locally and furnished it with many historical and topical discursions, including the method of iron-making that took place adjacent to the site.[14] This appeared in two guide books, the most popular of which was Charles Heath's Historical and Descriptive Accounts of the Ancient and Present State of Tintern Abbey, that went through many editions from 1793 onwards.[15]

William Wordsworth’s poem "Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey, on revisiting the banks of the Wye during a tour, July 13, 1798", is often linked with the Abbey, although it does not actually mention the ruins.[16] Instead, it recalls an earlier visit five years before and comments on the beneficial internalisation of that memory.[17] Following a similar walking tour with friends, Robert Bloomfield also dedicated a long poem to “The Banks of the Wye” (1811) in which the Abbey is only mentioned briefly as one of many items on the way.[18] However, that was followed in 1825 by yet another long poem dealing with the area, annotated and in four books, by Edward Collins: Tintern Abbey or the Beauties of Piercefield (1825).[19]

Edward Jerningham’s earlier short lyric, “Tintern Abbey”, written in 1796, followed Gilpin, whom he quoted, in commenting on the mournful lesson of the past.[20] Two poems of about that time also moralised on a visit to the ruins. Edmund Gardner, in his “Sonnet written in Tintern Abbey”, concludes with the line that 'Man’s but a temple of a shorter date',[21] while Luke Booker, in his “Original sonnet composed on leaving Tintern Abbey and proceeding with a party of friends down the River Wye to Chepstow”, hopes at death to sail as peacefully to the 'eternal Ocean'.[22]Richard Monckton Milnes' sonnet on “Tintern Abbey” dates from 1840.[23] It is also known that Tennyson’s “Tears, Idle Tears” (1847) was composed on a visit, but no mention of the Abbey appears there and the poem refers to personal feelings.[24]

An aquatint of the Abbey from Gilpin's Observations on the River Wye

In 1816, the abbey was made the backdrop to Sophia F. Ziegenhirt’s three-volume novel of Gothic horror, The Orphan of Tintern Abbey,[25] dismissed by The Monthly Review as “of the most ordinary class, in which the construction of the sentences and that of the story are equally confused.”[26] In a much more successful novel published two years earlier, Jane Austen described the decorations of Fanny Price's sitting room at Mansfield Park that included three fashionable transparencies, one of which featured the Abbey.[27]

Gilpin’s work on the Wye dealt not simply with the picturesque as a pictorial quality but with the added appeal of Gothic associations, as in the case of Tintern Abbey.[28] The visiting artists Francis Towne (1777),[29]Thomas Gainsborough (1782),[30]Thomas Girtin (1793),[31] and J.M.W. Turner in the 1794–95 series now at the Tate[32] and the British Museum, depicted details of the Abbey's stonework.[33][34] So did Samuel Palmer (see Gallery) and Thomas Creswick in the 19th century.[35][36]

Charles Heath, in his 1793 guide, commented on the picturesque quality of light in the "inimitable" effect of the harvest moon shining through the main window.[37] Once the railway arrived in 1876, steam excursions to the site were organised in the 1880s to Tintern station at that season to view the moon through the rose window.[38] Decades earlier, Peter van Lerberghe’s interior of 1812, with its tourist guides[39] carrying burning torches, showed the abbey lit by these and by moonlight (see Gallery). Paintings of the abbey at a distance include John Warwick Smith’s 1779 moonlit scene of the ruins,[40] sunsets by Samuel Palmer[41] and Benjamin Williams Leader,[42] and the later colour study by Turner in which the building appears as what Matthew Imms describes as a "dark shape at the centre" beneath slanting sunlight (see Gallery).[43][44]

Industry and access

The area adjacent to the abbey became industrialised from the mid-16th century with the setting up of the first wireworks by the Company of Mineral and Battery Works and the later expansion of factories and furnaces up the Angidy valley. Charcoal was made in the woods to feed these operations and, in addition, the hillside above the Abbey was quarried for the making of lime at a kiln in constant operation for some two centuries.[45] The site was in consequence subject to a degree of pollution[46] and the ruins themselves were inhabited by the local workers. J.T.Barber, for example, remarked on “passing the works of an iron foundry and a train of miserable cottages engrafted on the offices of the Abbey” on his approach.[47]

The WVR branch line bridge to the wire works

Until the 19th century, the local roads were rough and dangerous and the easiest access to the site was by boat. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, while trying to reach Tintern from Chepstow on a tour with friends in 1795, almost rode his horse over the edge of a quarry when they became lost in the dark.[48] It was not until 1829 that the new Wye Valley turnpike was completed, cutting through the abbey precinct.[49] In 1876 the Wye Valley Railway opened a station for Tintern. Although the line itself crossed the river before reaching the village, a branch was built from it to the wire works, obstructing the view of the Abbey on the road approach from the north.

Not all tourists were shocked by the intrusion of industry, however. Joseph Cottle and Robert Southey set out to view the ironworks at midnight on their 1795 tour,[50] while others painted or sketched them during the following years.[51] A 1799 print of the Abbey by Edward Dayes includes the boat-landing near the ruins and some of the encroaching housing. In the background above are the cliffs of a lime quarry and smoke rising from the kiln (see the Gallery). Though Philip James de Loutherbourg’s 1805 painting of the ruins does not include the intrusive buildings commented on by others, it makes their inhabitants and animals a prominent feature. Even William Havell’s panorama of the valley from the south pictures smoke rising in the distance, much as Wordsworth had noted five years before “wreathes of smoke sent up in silence from among the trees” in his description of the scene.[52]

Heritage

In the 20th century ruined abbeys became the focus for scholars, and architectural and archaeological investigations were undertaken. In 1901 the Abbey was bought by the crown from the Duke of Beaufort for £15,000. It was recognised as a monument of national importance and repair and maintenance works began to be carried out. In 1914 the Office of Works was passed responsibility for the ruins, and major structural repairs and partial reconstructions were undertaken — the ivy considered so romantic by the early tourists was removed. In 1984 Cadw took over responsibility for the site, which was Grade I listed from 29 September 2000.[53] The arch of the Abbey's watergate, which led from the Abbey to the River Wye, still exists today as part of the nearby Anchor Inn.[54][55] The watergate arch was also Grade II listed from 29 September 2000.[56]

American poet Allen Ginsberg took an acid trip at Tintern Abbey on 28 July 1967, and wrote his poem "Wales Visitation" as a result. In the poem he wrote of:[57][58]

...the lambs on the tree-nooked hillside this day bleating

heard in Blake's old ear, & the silent thought of Wordsworth in eld Stillness

clouds passing through skeleton arches of Tintern Abbey—

Bard Nameless as the Vast, babble to Vastness!

The Abbey is the setting for both the 1969 Flirtations music video Nothing But A Heartache[59] and the 1988 Iron Maiden video Can I Play with Madness.

Gordon Masters' historical novel The Secrets of Tintern Abbey (2008) dramatises the turbulent 400-year history of the Cistercian community at the Abbey.[60]

Burials

- Isabel de Clare, 4th Countess of Pembroke

- Maud Marshal

Gallery

The north-east view by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1732

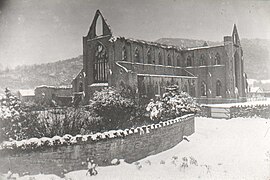

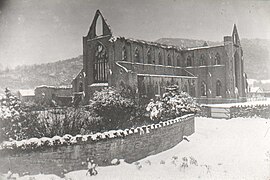

The abbey in the snow

Hillside view

The Abbey in a bend of the Wye, William Havell, 1804

South-East view, 1815

The River Wye landing, Edward Dayes, 1799

A J.M.W. Turner light effect, 1828

South Window, Frederick Calvert, 1815

Interior by moonlight, Peter van Lerberghe, 1812

Local use of the ruins, P.J.de Loutherbourg, 1805

Ruins against the hillside, Samuel Palmer, 1835

References

^ "Wales Visitor Attractions Survey 2015" (PDF). Welsh Government..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Round, J. H. (2004). "Clare, Walter de (d. 1137/8?)". In Hollister, C. Warren. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

[ISBN missing]

^ ab Newman, John (2000). Gwent/Monmouthshire. The Buildings of Wales. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071053-1.

[page needed]

^ Kelly's Directory of Monmouthshire, 1901

^ Robinson, David (2002). "Tintern Abbey". Welsh Historic Monuments (4th ed.). Cardiff. pp. 12–15.

[ISBN missing]

^ Cistercian Abbeys: TINTERN.

^ The National Archives and Kings College London, 'Fine Roll C 60/11, 3 Henry III', (Document), membrane 11 item 20

^ Fine Roll C 60/11, 3 Henry III membrane 11 item 20:

^ "Tintern Abbey". historyfish.net. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

^ Tintern Conservation Area survey, p.13

^ Gilpin, William, 1724-1804: "Observations on the river Wye, and several parts of South Wales, etc. : relative chiefly to picturesque beauty: made in the summer of the year 1770." Archived online Accessed 28 September 2017

^ Rev. Dr. Syned Davies “A Voyage to Tintern Abbey, in Monmouthshire, from Whitminster in Gloucestershire”. Epistle IV, in “THE LANGUAGE OF THE SENSE” Poetical Tintern at lib.umich.edu Accessed 28 September 2017

^ William Pine, 1786: "Chepstow; Or, A New Guide to Gentlemen and Ladies Whose Curiosity Leads Them to Visit Chepstow: Piercefield-walks, Tintern-abbey, etc." Google Books Accessed 28 September 2017

^ Rev. Duncomb Davis' poem, in “THE LANGUAGE OF THE SENSE” Poetical Tintern at lib.umich.edu University of Michigan Accessed 28 September 2017

^ Charles Heath: "Historical and Descriptive Accounts of the Ancient and Present State of Tintern Abbey" in “THE LANGUAGE OF THE SENSE” Poetical Tintern at lib.umich.edu University of Michigan Accessed 28 September 2017

^ Deborah Kennedy, "Wordsworth, Turner, and the Power of Tintern Abbey", Wordsworth Circle, Spring 2002

^ Gilpin, William, Observations on the river Wye, and several parts of South Wales, Page 46: Online text at rc.umd.edu Accessed 1 October 2017

^ Robert Bloomfield: The Banks of Wye: Poem Text II.65–88 Accessed 1 October 2017

^ Edward Collins "Tintern Abbey: or, The beauties of Piercefield: a poem: in four books: interspersed with illustrative notes" at University of Toronto Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Edward Jerningham “Tintern Abbey” in Poems and Plays, Vol.2, p.135 at Google Books Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Edmund Gardner, “Sonnet written in Tintern Abbey”: The sonnet originally appeared pseudonymously, accompanying a similarly moralising sonnet on the Severn in The European Magazine vol.30, p.119 at Google Books Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Booker's sonnet appeared in Charles Heath’s guide to Tintern Abbey

^ Richard Monckton Milnes: "Poetry for the People", p.87 “Tintern Abbey” Accessed 7 October 2017

^ James Gribble, Literary Education: a revaluation, Cambridge University 1983, pp.58–61

^ Marshall B. Tymn, Horror literature: a core collection and reference guide, R.R.Bowker, 1981, p.175

^ Sophia F. Ziegenhirt "The Orphan of Tintern Abbey" The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal Vol.79, p.439 at Google Books Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Jane Austen: "Mansfield Park" Standard novels edition, London 1833, p.135, at Google Books Accessed 7 October 2017

^ William Gilpin, Observations on the Rivery Wye, London 1882, pp.47

^ Francis Towne "The West Front of Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire", at Christies Accessed 9 October 2017

^ Thomas Gainsborough: "Tintern Abbey" 1782, at Tate Gallery Accessed 9 October 2017

^ Thomas Girtin: "Interior of Tintern Abbey looking toward the West Window", at Art Renewal Center Accessed 9 October 2017

^ J.M.W. Turner: "Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking towards the East Window" (detail) at Iconeye Accessed 9 October 2017

^ BM site Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine.

^ J.M.W. Turner: Tintern Abbey, west front; the ruined abbey, overgrown with grass and bushes... British Museum, Collection online Accessed 14 October 2017

^ BBC Arts Archived 2015-07-16 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Thomas Creswick (1811–1869) "Part of the Ruins of Tintern Abbey" Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council, at artuk.org Accessed 14 October 2017

^ Charles Heath, Historical and Descriptive Accounts of the Ancient and Present State of Tintern Abbey, Monmouth, p.91

^ Wye Valley, Old Station Tintern - history, at overlookingthewye.org.uk Accessed 7 October 2017

^ C.S.Matheson, "I wanted some intelligent guide", Romanticism, p.38

^ John Warwick Smith - moonlit scene of the ruins - at the Metropolitan Museum Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Samuel Palmer - "Tintern Abbey at Sunset" at Wikimedia Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Benjamin Williams Leader "Tintern Abbey" at Wikimedia Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Matthew Imms, "Tintern Abbey from the River Wye c.1828 by Joseph Mallord William Turner", catalogue entry, March 2013, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2013 Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Sandra Gibson, review of the 2012 Turner, Monet, Twombly exhibition at Tate Liverpool, Catalyst Media

^ Wye-Dean Tourism (exact ref not found) Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Charles J. Rzepka, Inventions and Interventions, ch.14, pp.189–222

^ .” J.T.Barber, A tour throughout South Wales and Monmouthshire, London 1803 p.266

^ Joseph Cottle, Early recollections: chiefly relating to the late Samuel Taylor Coleridge, London 1837, pp.43–50

^ Cadw, Lower Wye Valley

^ Joseph Cottle, Early Recollections pp.50–1

^ See the 1798 print of “Iron Mills, A View near Tintern Abbey" belonging to the National Library of Wales and James Ward’s 1807 sketch of “Mr Thompson’s Wire Mill, Tintern” at the Yale Center for British Art

^ ”Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey”, lines 18–19

^ "Abbey Church of St Mary (Tintern Abbey) including monastic buildings – Tintern – Monmouthshire – Wales". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

^ fotolibra.com (showing the Abbey watergate attached to the Anchor Inn). "The Anchor Inn Tintern Wye Valley Wales". Fotolibra. Retrieved 23 Nov 2017.

^ visitmonmouthshire.com (mentions the Abbey watergate). "The Anchor Inn". Visit Monmouthshire. Retrieved 23 Nov 2017.

^ "The Anchor P H including the Watergate, Tintern". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 2017-03-02.

^ Ginsberg: A biography by Barry Miles, Virgin Publishing 2000 p394

^ Allan Ginsburg's 'Wales Visitation' 2010-01-31, accessed 2012-01-01

^ "Nothing But A Heartache" by The Flirtations at Song Facts Accessed 7 October 2017

^ Gordon Masters, The Secrets of Tintern Abbey: A Historical Novel, Wheatmark, 2008 Accessed 7 October 2017

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tintern Abbey, Wales. |

"Tintern Abbey visitor information". Cadw.

- Tintern Abbey information at Castlewales.com

- Tintern Abbey – A Virtual Experience

- Cistercian Abbeys: Tintern

- Tintern and Other British Cistercian Abbey Photo Pages

- Enchanting Ruin: Tintern Abbey and Romantic Tourism in Wales

- The Tintern Village Website