Albert, Prince Consort

| Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prince Consort | |||||

Portrait by Winterhalter, 1859 | |||||

| Consort of the British monarch | |||||

| Tenure | 10 February 1840 – 14 December 1861 | ||||

| Born | (1819-08-26)26 August 1819 Schloss Rosenau, Coburg | ||||

| Died | 14 December 1861(1861-12-14) (aged 42) Windsor Castle | ||||

| Burial | 23 December 1861 St George's Chapel; 18 December 1862 Frogmore Mausoleum | ||||

| Spouse | Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom (m. 1840) | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House |

| ||||

| Father | Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Mother | Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg | ||||

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Francis Albert Augustus Charles Emmanuel;[1] 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the husband of Queen Victoria.

He was born in the Saxon duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, to a family connected to many of Europe's ruling monarchs. At the age of 20, he married his first cousin, Queen Victoria; they had nine children. Initially he felt constrained by his role of consort, which did not afford him power or responsibilities. He gradually developed a reputation for supporting public causes, such as educational reform and the abolition of slavery worldwide, and was entrusted with running the Queen's household, office and estates. He was heavily involved with the organisation of the Great Exhibition of 1851, which was a resounding success.

Victoria came to depend more and more on his support and guidance. He aided the development of Britain's constitutional monarchy by persuading his wife to be less partisan in her dealings with Parliament—although he actively disagreed with the interventionist foreign policy pursued during Lord Palmerston's tenure as Foreign Secretary. In 1857, Albert was given the formal title of Prince Consort.

Albert died at the relatively young age of 42. Victoria was so devastated at the loss of her husband that she entered into a deep state of mourning and wore black for the rest of her life. On her death in 1901, their eldest son succeeded as Edward VII, the first British monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, named after the ducal house to which Albert belonged.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Marriage

3 Consort of the Queen

4 Reformer and innovator

5 Family and public life (1852–1859)

6 Illness and death

7 Legacy

8 Titles, styles, honours and arms

8.1 Titles and styles

8.2 Honours

8.3 Arms

9 Issue

10 Ancestry

11 See also

12 References

13 Sources

14 External links

Early life

Albert (left) with his elder brother Ernest and mother Louise, shortly before her exile from court

Albert was born at Schloss Rosenau, near Coburg, Germany, the second son of Ernest III, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and his first wife, Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.[2] Albert's future wife, Victoria, was born earlier in the same year with the assistance of the same midwife, Charlotte von Siebold.[3] Albert was baptised into the Lutheran Evangelical Church on 19 September 1819 in the Marble Hall at Schloss Rosenau with water taken from the local river, the Itz.[4] His godparents were his paternal grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld; his maternal grandfather, the Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg; the Emperor of Austria; the Duke of Teschen; and Emanuel, Count of Mensdorff-Pouilly.[5] In 1825, Albert's great-uncle, Frederick IV, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, died. His death led to a realignment of Saxon duchies the following year and Albert's father became the first reigning duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.[6]

Albert and his elder brother, Ernest, spent their youth in a close companionship marred by their parents' turbulent marriage and eventual separation and divorce.[7] After their mother was exiled from court in 1824, she married her lover, Alexander von Hanstein, Count of Polzig and Beiersdorf. She presumably never saw her children again, and died of cancer at the age of 30 in 1831.[8] The following year, their father married his niece, his sons' cousin Princess Marie of Württemberg; their marriage was not close, however, and Marie had little—if any—impact on her stepchildren's lives.[9]

The brothers were educated privately at home by Christoph Florschütz and later studied in Brussels, where Adolphe Quetelet was one of their tutors.[10] Like many other German princes, Albert attended the University of Bonn, where he studied law, political economy, philosophy and the history of art. He played music and excelled at sport, especially fencing and riding.[11] His tutors at Bonn included the philosopher Fichte and the poet Schlegel.[12]

Marriage

Portrait by John Partridge, 1840

The idea of marriage between Albert and his cousin, Victoria, was first documented in an 1821 letter from his paternal grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, who said that he was "the pendant to the pretty cousin".[13] By 1836, this idea had also arisen in the mind of their ambitious uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831.[14] At this time, Victoria was the heir presumptive to the British throne. Her father, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the fourth son of King George III, had died when she was a baby, and her elderly uncle, King William IV, had no legitimate children. Her mother, the Duchess of Kent, was the sister of both Albert's father—the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha—and King Leopold. Leopold arranged for his sister, Victoria's mother, to invite the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and his two sons to visit her in May 1836, with the purpose of meeting Victoria. William IV, however, disapproved of any match with the Coburgs, and instead favoured the suit of Prince Alexander, second son of the Prince of Orange. Victoria was well aware of the various matrimonial plans and critically appraised a parade of eligible princes.[15] She wrote, "[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful."[16] Alexander, on the other hand, she described as "very plain".[16]

Victoria wrote to her uncle Leopold to thank him "for the prospect of great happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear Albert ... He possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly happy."[17] Although the parties did not undertake a formal engagement, both the family and their retainers widely assumed that the match would take place.[18]

Victoria came to the throne aged eighteen on 20 June 1837. Her letters of the time show interest in Albert's education for the role he would have to play, although she resisted attempts to rush her into marriage.[19] In the winter of 1838–39, the prince visited Italy, accompanied by the Coburg family's confidential adviser, Baron Stockmar.[20]

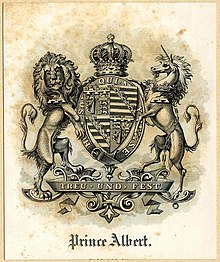

Armorial bookplate of Prince Albert

Albert returned to the United Kingdom with Ernest in October 1839 to visit the Queen, with the objective of settling the marriage.[21] Albert and Victoria felt mutual affection and the Queen proposed to him on 15 October 1839.[22] Victoria's intention to marry was declared formally to the Privy Council on 23 November,[23] and the couple married on 10 February 1840 at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace.[24] Just before the marriage, Albert was naturalised by Act of Parliament,[25] and granted the style of Royal Highness by an Order in Council.[1]

Initially Albert was not popular with the British public; he was perceived to be from an impoverished and undistinguished minor state, barely larger than a small English county.[26] The British Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, advised the Queen against granting her husband the title of "King Consort"; Parliament also objected to Albert being created a peer—partly because of anti-German sentiment and a desire to exclude Albert from any political role.[27] Albert's religious views provided a small amount of controversy when the marriage was debated in Parliament: although as a member of the Lutheran Evangelical Church Albert was a Protestant, the non-Episcopal nature of his church was considered worrisome.[28] Of greater concern, however, was that some of Albert's family were Roman Catholic.[29] Melbourne led a minority government and the opposition took advantage of the marriage to weaken his position further. They opposed the ennoblement of Albert and granted him a smaller annuity than previous consorts,[30] £30,000 instead of the usual £50,000.[31] Albert claimed that he had no need of a British peerage, writing: "It would almost be a step downwards, for as a Duke of Saxony, I feel myself much higher than a Duke of York or Kent."[32] For the next seventeen years, Albert was formally titled "HRH Prince Albert" until, on 25 June 1857, Victoria formally granted him the title Prince Consort.[33]

Consort of the Queen

Portrait by Winterhalter, 1842

The position in which the prince was placed by his marriage, while one of distinction, also offered considerable difficulties; in Albert's own words, "I am very happy and contented; but the difficulty in filling my place with the proper dignity is that I am only the husband, not the master in the house."[34] The Queen's household was run by her former governess,[35]Baroness Lehzen. Albert referred to her as the "House Dragon", and manoeuvred to dislodge the Baroness from her position.[36]

Within two months of the marriage, Victoria was pregnant. Albert started to take on public roles; he became President of the Society for the Extinction of Slavery (slavery had already been abolished throughout the British Empire, but was still lawful in places such as the United States and the colonies of France); and helped Victoria privately with her government paperwork.[37] In June 1840, while on a public carriage ride, Albert and the pregnant Victoria were shot at by Edward Oxford, who was later judged insane. Neither Albert nor Victoria was hurt and Albert was praised in the newspapers for his courage and coolness during the attack.[38] Albert was gaining public support as well as political influence, which showed itself practically when, in August, Parliament passed the Regency Act 1840 to designate him regent in the event of Victoria's death before their child reached the age of majority.[39] Their first child, Victoria, named after her mother, was born in November. Eight other children would follow over the next seventeen years. All nine children survived to adulthood, a fact which biographer Hermione Hobhouse credited to Albert's "enlightened influence" on the healthy running of the nursery.[40] In early 1841, he successfully removed the nursery from Lehzen's pervasive control, and in September 1842, Lehzen left Britain permanently—much to Albert's relief.[41]

After the 1841 general election, Melbourne was replaced as Prime Minister by Sir Robert Peel, who appointed Albert as chairman of the Royal Commission in charge of redecorating the new Palace of Westminster. The Palace had burned down seven years before, and was being rebuilt. As a patron and purchaser of pictures and sculpture, the commission was set up to promote the fine arts in Britain. The commission's work was slow, and the architect, Charles Barry, took many decisions out of the commissioners' hands by decorating rooms with ornate furnishings that were treated as part of the architecture.[42] Albert was more successful as a private patron and collector. Among his notable purchases were early German and Italian paintings—such as Lucas Cranach the Elder's Apollo and Diana and Fra Angelico's St Peter Martyr—and contemporary pieces from Franz Xaver Winterhalter and Edwin Landseer.[43]Ludwig Gruner, of Dresden, assisted Albert in buying pictures of the highest quality.[44]

Albert and Victoria were shot at again on both 29 and 30 May 1842, but were unhurt. The culprit, John Francis, was detained and condemned to death,[45] although he was later reprieved.[46] Some of their early unpopularity came about because of their stiffness and adherence to protocol in public, though in private the couple were more easy-going.[47] In early 1844, Victoria and Albert were apart for the first time since their marriage when he returned to Coburg on the death of his father.[48]

Osborne House, Isle of Wight, UK

By 1844, Albert had managed to modernise the royal finances and, through various economies, had sufficient capital to purchase Osborne House on the Isle of Wight as a private residence for their growing family.[49] Over the next few years a house modelled in the style of an Italianate villa was built to the designs of Albert and Thomas Cubitt.[50] Albert laid out the grounds, and improved the estate and farm.[51] Albert managed and improved the other royal estates; his model farm at Windsor was admired by his biographers,[52] and under his stewardship the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall—the hereditary property of the Prince of Wales—steadily increased.[53]

Unlike many landowners who approved of child labour and opposed Peel's repeal of the Corn Laws, Albert supported moves to raise working ages and free up trade.[54] In 1846, Albert was rebuked by Lord George Bentinck when he attended the debate on the Corn Laws in the House of Commons to give tacit support to Peel.[55] During Peel's premiership, Albert's authority behind, or beside, the throne became more apparent. He had access to all the Queen's papers, was drafting her correspondence[56] and was present when she met her ministers, or even saw them alone in her absence.[57] The clerk of the Privy Council, Charles Greville, wrote of him: "He is King to all intents and purposes."[58]

Reformer and innovator

Early daguerreotype with hand-colouring, 1848

In 1847, Albert was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge after a close contest with the Earl of Powis.[59] Albert used his position as Chancellor to campaign successfully for reformed and more modern university curricula, expanding the subjects taught beyond the traditional mathematics and classics to include modern history and the natural sciences.[60]

That summer, Victoria and Albert spent a rainy holiday in the west of Scotland at Loch Laggan, but heard from their doctor, Sir James Clark, that his son had enjoyed dry, sunny days farther east at Balmoral Castle. The tenant of Balmoral, Sir Robert Gordon, died suddenly in early October, and Albert began negotiations to take over the lease from the owner, the Earl Fife.[61] In May the following year, Albert leased Balmoral, which he had never visited, and in September 1848 he, his wife and the older children went there for the first time.[62] They came to relish the privacy it afforded.[63]

Revolutions spread throughout Europe in 1848 as the result of a widespread economic crisis. Throughout the year, Victoria and Albert complained about Foreign Secretary Palmerston's independent foreign policy, which they believed destabilised foreign European powers further.[64] Albert was concerned for many of his royal relatives, a number of whom were deposed. He and Victoria, who gave birth to their daughter Louise during that year, spent some time away from London in the relative safety of Osborne. Although there were sporadic demonstrations in England, no effective revolutionary action took place, and Albert even gained public acclaim when he expressed paternalistic, yet well-meaning and philanthropic, views.[65] In a speech to the Society for the Improvement of the Condition of the Labouring Classes, of which he was President, he expressed his "sympathy and interest for that class of our community who have most of the toil and fewest of the enjoyments of this world".[66] It was the "duty of those who, under the blessings of Divine Providence, enjoy station, wealth, and education" to assist those less fortunate than themselves.[66]

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was housed in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London.

A man of progressive and relatively liberal ideas, Albert not only led reforms in university education, welfare, the royal finances and slavery, he had a special interest in applying science and art to the manufacturing industry.[67] The Great Exhibition of 1851 arose from the annual exhibitions of the Society of Arts, of which Albert was President from 1843, and owed most of its success to his efforts to promote it.[53][68] Albert served as president of the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, and had to fight for every stage of the project.[69] In the House of Lords, Lord Brougham fulminated against the proposal to hold the exhibition in Hyde Park.[70] Opponents of the exhibition prophesied that foreign rogues and revolutionists would overrun England, subvert the morals of the people, and destroy their faith.[71] Albert thought such talk absurd and quietly persevered, trusting always that British manufacturing would benefit from exposure to the best products of foreign countries.[53]

The Queen opened the exhibition in a specially designed and built glass building known as the Crystal Palace on 1 May 1851. It proved a colossal success.[72] A surplus of £180,000 was used to purchase land in South Kensington on which to establish educational and cultural institutions—including the Natural History Museum, Science Museum, Imperial College London and what would later be named the Royal Albert Hall and the Victoria and Albert Museum.[73] The area was referred to as "Albertopolis" by sceptics.[74]

Family and public life (1852–1859)

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854

In 1852, John Camden Neild, an eccentric miser, left Victoria an unexpected legacy, which Albert used to obtain the freehold of Balmoral. As usual, he embarked on an extensive programme of improvements.[75] The same year, he was appointed to several of the offices left vacant by the death of the Duke of Wellington, including the mastership of Trinity House and the colonelcy of the Grenadier Guards.[76] With Wellington's passing, Albert was able to propose and campaign for modernisation of the army, which was long overdue.[77] Thinking that the military was unready for war, and that Christian rule was preferable to Islamic rule, Albert counselled a diplomatic solution to conflict between the Russian and Ottoman empires. Palmerston was more bellicose, and favoured a policy that would prevent further Russian expansion.[78] Palmerston was manoeuvred out of the cabinet in December 1853, but at about the same time a Russian fleet attacked the Ottoman fleet at anchor at Sinop. The London press depicted the attack as a criminal massacre, and Palmerston's popularity surged as Albert's fell.[79] Within two weeks, Palmerston was re-appointed as a minister. As public outrage at the Russian action continued, false rumours circulated that Albert had been arrested for treason and was being held prisoner in the Tower of London.[80]

By March 1854, Britain and Russia were embroiled in the Crimean War. Albert devised a master-plan for winning the war by laying siege to Sevastopol while starving Russia economically, which became the Allied strategy after the Tsar decided to fight a purely defensive war.[81] Early British optimism soon faded as the press reported that British troops were ill-equipped and mismanaged by aged generals using out-of-date tactics and strategy. The conflict dragged on as the Russians were as poorly prepared as their opponents. The Prime Minister, Lord Aberdeen, resigned and Palmerston succeeded him.[82] A negotiated settlement eventually put an end to the war with the Treaty of Paris. During the war, Albert arranged to marry his fourteen-year-old daughter, Victoria, to Prince Frederick William of Prussia, though Albert delayed the marriage until Victoria was seventeen. Albert hoped that his daughter and son-in-law would be a liberalising influence in the enlarging but very conservative Prussian state.[83]

Prince Albert, Queen Victoria and their nine children, 1857. Left to right: Alice, Arthur, Albert (Prince Consort), Albert Edward (Prince of Wales), Leopold, Louise, Queen Victoria with Beatrice, Alfred, Victoria and Helena[84]

Albert promoted many public educational institutions. Chiefly at meetings in connection with these he spoke of the need for better schooling.[85] A collection of his speeches was published in 1857. Recognised as a supporter of education and technological progress, he was invited to speak at scientific meetings, such as the memorable address he delivered as president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science when it met at Aberdeen in 1859.[86] His espousal of science met with clerical opposition; he and Palmerston unsuccessfully recommended a knighthood for Charles Darwin, after the publication of On the Origin of Species, which was opposed by the Bishop of Oxford.[87]

Albert continued to devote himself to the education of his family and the management of the royal household.[88] His children's governess, Lady Lyttelton, thought him unusually kind and patient, and described him joining in family games with enthusiasm.[89] He felt keenly the departure of his eldest daughter for Prussia when she married her fiancé at the beginning of 1858,[90] and was disappointed that his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, did not respond well to the intense educational programme that Albert had designed for him.[91] At the age of seven, the Prince of Wales was expected to take six hours of instruction, including an hour of German and an hour of French every day.[92] When the Prince of Wales failed at his lessons, Albert caned him.[93] Corporal punishment was common at the time, and was not thought unduly harsh.[94] Albert's biographer Roger Fulford wrote that the relationships between the family members were "friendly, affectionate and normal ... there is no evidence either in the Royal Archives or in the printed authorities to justify the belief that the relations between the Prince and his eldest son were other than deeply affectionate."[95]Philip Magnus wrote in his biography of Albert's eldest son that Albert "tried to treat his children as equals; and they were able to penetrate his stiffness and reserve because they realised instinctively not only that he loved them but that he enjoyed and needed their company."[96]

Illness and death

Photograph by J. J. E. Mayall, 1860

In August 1859, Albert fell seriously ill with stomach cramps.[97] He had an accidental brush with death during a trip to Coburg in the autumn of 1860, when he was driving alone in a carriage drawn by four horses that suddenly bolted. As the horses continued to gallop toward a stationary wagon waiting at a railway crossing, Albert jumped for his life from the carriage. One of the horses was killed in the collision, and Albert was badly shaken, though his only physical injuries were cuts and bruises. He confided in his brother and eldest daughter that he had sensed his time had come.[98]

In March 1861, Victoria's mother and Albert's aunt, the Duchess of Kent, died and Victoria was grief-stricken; Albert took on most of the Queen's duties, despite continuing to suffer with chronic stomach trouble.[99] The last public event he presided over was the opening of the Royal Horticultural Gardens on 5 June 1861.[100] In August, Victoria and Albert visited the Curragh Camp, Ireland, where the Prince of Wales was doing army service. At the Curragh, the Prince of Wales was introduced, by his fellow officers, to Nellie Clifden, an Irish actress.[101]

By November, Victoria and Albert had returned to Windsor, and the Prince of Wales had returned to Cambridge, where he was a student. Two of Albert's young cousins, brothers King Pedro V of Portugal and Prince Ferdinand, died of typhoid fever within 5 days of each other in early November.[102] On top of this news, Albert was informed that gossip was spreading in gentlemen's clubs and the foreign press that the Prince of Wales was still involved with Nellie Clifden.[103] Albert and Victoria were horrified by their son's indiscretion, and feared blackmail, scandal or pregnancy.[104] Although Albert was ill and at a low ebb, he travelled to Cambridge to see the Prince of Wales on 25 November[105] to discuss his son's indiscreet affair.[53] In his final weeks Albert suffered from pains in his back and legs.[106]

When the Trent Affair—the forcible removal of Confederate envoys from a British ship by Union forces during the American Civil War—threatened war between the United States and Britain, Albert was gravely ill but intervened to soften the British diplomatic response.[107]

On 9 December, one of Albert's doctors, William Jenner, diagnosed typhoid fever. Albert died at 10:50 p.m. on 14 December 1861 in the Blue Room at Windsor Castle, in the presence of the Queen and five of their nine children.[108] The contemporary diagnosis was typhoid fever, but modern writers have pointed out that Albert’s ongoing stomach pain, leaving him ill for at least two years before his death, may indicate that a chronic disease, such as Crohn's disease,[109]renal failure, or abdominal cancer, was the cause of death.[110]

Legacy

The Albert Memorial in Hyde Park, London

Royal Albert Hall, London

The Queen's grief was overwhelming, and the tepid feelings the public had felt previously for Albert were replaced by sympathy.[111] Victoria wore black mourning for the rest of her long life, and Albert's rooms in all his houses were kept as they had been, even with hot water brought in the morning and linen and towels changed daily.[112] Such practices were not uncommon in the houses of the very rich.[113] Victoria withdrew from public life and her seclusion eroded some of Albert's work in attempting to re-model the monarchy as a national institution setting a moral, if not political, example.[114] Albert is credited with introducing the principle that the British royal family should remain above politics.[115] Before his marriage to Victoria, she supported the Whigs; for example, early in her reign Victoria managed to thwart the formation of a Tory government by Sir Robert Peel by refusing to accept substitutions which Peel wanted to make among her ladies-in-waiting.[116]

Albert's body was temporarily entombed in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[117] A year after his death his remains were deposited at Frogmore Mausoleum, which remained incomplete until 1871.[118] The sarcophagus, in which both he and the Queen were eventually laid, was carved from the largest block of granite that had ever been quarried in Britain.[119] Despite Albert's request that no effigies of him should be raised, many public monuments were erected all over the country and across the British Empire.[120] The most notable are the Royal Albert Hall and the Albert Memorial in London. The plethora of memorials erected to Albert became so great that Charles Dickens told a friend that he sought an "inaccessible cave" to escape from them.[121]

Places and objects named after Albert range from Lake Albert in Africa to the city of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, to the Albert Medal presented by the Royal Society of Arts. Four regiments of the British Army were named after him: 11th (Prince Albert's Own) Hussars; Prince Albert's Light Infantry; Prince Albert's Own Leicestershire Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry, and The Prince Consort's Own Rifle Brigade. He and Queen Victoria showed a keen interest in the establishment and development of Aldershot in Hampshire as a garrison town in the 1850s. They had a wooden Royal Pavilion built there in which they would often stay when attending reviews of the army.[122] Albert established and endowed the Prince Consort's Library at Aldershot, which still exists today.[123]

Biographies published after his death were typically heavy on eulogy. Theodore Martin's five-volume magnum opus was authorised and supervised by Queen Victoria, and her influence shows in its pages. Nevertheless, it is an accurate and exhaustive account.[124]Lytton Strachey's Queen Victoria (1921) was more critical, but it was discredited in part by mid-twentieth-century biographers such as Hector Bolitho and Roger Fulford, who (unlike Strachey) had access to Victoria's journal and letters.[125] Popular myths about Prince Albert—such as the claim that he introduced Christmas trees to Britain—are dismissed by scholars.[126] Recent biographers such as Stanley Weintraub portray Albert as a figure in a tragic romance who died too soon and was mourned by his lover for a lifetime.[53] In the 2009 movie The Young Victoria, Albert, played by Rupert Friend, is made into a heroic character; in the fictionalised depiction of the 1840 shooting, he is struck by a bullet—something that did not happen in real life.[127][128]

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

Albert robed as a Knight Grand Cross of the Bath, 1842

In Britain, Albert was styled His Serene Highness Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in the months before his marriage,[25] until granted the style of Royal Highness on 6 February 1840.[1] He was given the title of Prince Consort on 25 June 1857.[33]

Honours

British

KG: Knight of the Garter, 16 December 1839[129]

KT: Knight of the Thistle[130]

KP: Knight of St Patrick[130]

GCB: Order of the Bath

- Knight Grand Cross, 6 March 1840[131]

- Great Master, 25 May 1847[132]

- Knight Grand Cross, 6 March 1840[131]

KSI: Extra Knight of the Star of India, 25 June 1861[133]

GCMG: Knight Grand Cross of St Michael and St George[130]

Foreign

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold: wedding gift of his uncle, King Leopold, 1839[134]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold: wedding gift of his uncle, King Leopold, 1839[134]

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 27 April 1841[135]

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 27 April 1841[135]

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 10 January 1843[136]

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 10 January 1843[136]

Austria: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen of Hungary, 1843[137]

Austria: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen of Hungary, 1843[137]

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, February 1856[138]

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, February 1856[138]

Arms

Coat of arms of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha as granted in 1840

Upon his marriage to Queen Victoria in 1840, Prince Albert received a personal grant of arms, being the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom differenced by a white three-point label with a red cross in the centre, quartered with his ancestral arms of Saxony.[1][139] They are blazoned: "Quarterly, 1st and 4th, the Royal Arms, with overall a label of three points Argent charged on the centre with cross Gules; 2nd and 3rd, Barry of ten Or and Sable, a crown of rue in bend Vert".[140] The arms are unusual, being described by S. T. Aveling as a "singular example of quartering differenced arms, [which] is not in accordance with the rules of Heraldry, and is in itself an heraldic contradiction."[141] Prior to his marriage Albert used the arms of his father undifferenced, in accordance with German custom.

Albert's Garter stall plate displays his arms surmounted by a royal crown with six crests for the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; these are from left to right: 1. "A bull's head caboshed Gules armed and ringed Argent, crowned Or, the rim chequy Gules and Argent" for Mark. 2. "Out of a coronet Or, two buffalo horns Argent, attached to the outer edge of five branches fesswise each with three linden leaves Vert" for Thuringia. 3. "Out of a coronet Or, a pyramidal chapeau charged with the arms of Saxony ensigned by a plume of peacock feathers Proper out of a coronet also Or" for Saxony. 4. "A bearded man in profile couped below the shoulders clothed paly Argent and Gules, the pointed coronet similarly paly terminating in a plume of three peacock feathers" for Meissen. 5. "A demi griffin displayed Or, winged Sable, collared and langued Gules" for Jülich. 6. "Out of a coronet Or, a panache of peacock feathers Proper" for Berg.[140]

The supporters were the crowned lion of England and the unicorn of Scotland (as in the Royal Arms) charged on the shoulder with a label as in the arms. Albert's personal motto is the German Treu und Fest (Loyal and Sure).[140] This motto was also used by Prince Albert's Own or the 11th Hussars.

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes[142] |

|---|---|---|---|

Victoria, Princess Royal | 21 November 1840 | 5 August 1901 | married 1858, Crown Prince Frederick, later Frederick III, German Emperor; had issue |

Edward VII of the United Kingdom | 9 November 1841 | 6 May 1910 | married 1863, Princess Alexandra of Denmark; had issue |

Princess Alice | 25 April 1843 | 14 December 1878 | married 1862, Prince Louis, later Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine; had issue |

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | 6 August 1844 | 30 July 1900 | married 1874, Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia; had issue |

Princess Helena | 25 May 1846 | 9 June 1923 | married 1866, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein; had issue |

Princess Louise | 18 March 1848 | 3 December 1939 | married 1871, John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, later 9th Duke of Argyll; no issue |

Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn | 1 May 1850 | 16 January 1942 | married 1879, Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia; had issue |

Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany | 7 April 1853 | 28 March 1884 | married 1882, Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont; had issue |

Princess Beatrice | 14 April 1857 | 26 October 1944 | married 1885, Prince Henry of Battenberg; had issue |

Prince Albert's 42 grandchildren included four reigning monarchs: King George V of the United Kingdom; Wilhelm II, German Emperor; Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse; and Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and five consorts of monarchs: Queens Maud of Norway, Sophia of Greece, Victoria Eugenie of Spain, Marie of Romania, and Empress Alexandra of Russia. Albert's many descendants include royalty and nobility throughout Europe.

Victoria and Albert's family in 1846 by Franz Xaver Winterhalter left to right: Prince Alfred and the Prince of Wales; the Queen and Prince Albert; Princesses Alice, Helena and Victoria

Ancestry

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Albert, Prince Consort | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- John Brown

- List of coupled cousins

- Royal Albert Memorial Museum

References

^ abcd "No. 19821". The London Gazette. 7 February 1840. p. 241..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 2; Weintraub 1997, p. 20; Weir 1996, p. 305.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 20.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 21.

^ Ames 1968, p. 1; Hobhouse 1983, p. 2.

^ e.g. Montgomery-Massingberd 1977, pp. 259–273.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 25–28.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 4; Weintraub 1997, pp. 25–28.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 40–41.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 16.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 60–62.

^ Ames 1968, p. 15; Weintraub 1997, pp. 56–60.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 15.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 15–16; Weintraub 1997, pp. 43–49.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 43–49.

^ ab Victoria quoted in Weintraub 1997, p. 49.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 51.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 53, 58, 64, 65.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 62.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 17–18; Weintraub 1997, p. 67.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 42; Weintraub 1997, pp. 77–81.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 42–43; Hobhouse 1983, p. 20; Weintraub 1997, pp. 77–81.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 45; Hobhouse 1983, p. 21; Weintraub 1997, p. 86.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 52; Hobhouse 1983, p. 24.

^ ab "No. 19826". The London Gazette. 14 February 1840. p. 302.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 45.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 88.

^ Abecasis-Phillips 2004.

^ Murphy 2001, pp. 28–31.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 8–9, 89.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 47; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 23–24.

^ Quoted in Jagow 1938, p. 37.

^ ab "No. 22015". The London Gazette. 26 June 1857. p. 2195.

^ Albert to William von Lowenstein, May 1840, quoted in Hobhouse 1983, p. 26.

^ Or more properly "Lady Attendant".

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 59–74.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 102–105.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 106–107.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 107.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 28.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 73–74.

^ Ames 1968, pp. 48–55; Fulford 1949, pp. 212–213; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 82–88.

^ Ames 1968, pp. 132–146, 200–222; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 70–78. The National Gallery, London, received 25 paintings in 1863 presented by Queen Victoria at the Prince Consort's wish. See external links for works in the Royal Collection.

^ Cust 1907, pp. 162–170.

^ Old Bailey Proceedings Online, Trial of John Francis. (t18420613-1758, 13 June 1842).

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 134–135.

^ Ames 1968, p. 172; Fulford 1949, pp. 95–104; Weintraub 1997, p. 141.

^ Ames 1968, p. 60; Weintraub 1997, p. 154.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 79; Hobhouse 1983, p. 131; Weintraub 1997, p. 158.

^ Ames 1968, pp. 61–71; Fulford 1949, p. 79; Hobhouse 1983, p. 121; Weintraub 1997, p. 181.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 127, 131.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 88–89; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 121–127.

^ abcde Weintraub 2004.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 116.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 116; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 39–40.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 36–37.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 118.

^ Greville's diary volume V, p. 257 quoted in Fulford 1949, p. 117.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 195–196; Hobhouse 1983, p. 65; Weintraub 1997, pp. 182–184.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 198–199; Hobhouse 1983, p. 65; Weintraub 1997, pp. 187, 207.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 189–191.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 193, 212, 214, 203, 206.

^ Extracts from the Queen's journal of the holidays were published in 1868 as Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 119–128; Weintraub 1997, pp. 193, 212, 214 and 264–265.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 192–201.

^ ab The text of the speech was widely reproduced, e.g. "The Condition of the Labouring Classes". The Times, 19 May 1848, p. 6.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 216–217; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 89–108.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 219–220.

^ e.g. Fulford 1949, p. 221.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 220.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 217–222.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 222; Hobhouse 1983, p. 110.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 110.

^ Ames 1968, p. 120; Hobhouse 1983, p. x; Weintraub 1997, p. 263.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 145.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 270–274, 281–282.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 42–43, 47–50; Weintraub 1997, pp. 274–276.

^ e.g. Fulford 1949, pp. 128, 153–157.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 288–293.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 156–157; Weintraub 1997, pp. 294–302.

^ Stewart 2012, pp. 153–154.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 303–322, 328.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 326, 330.

^ Finestone 1981, p. 36.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 63.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, p. 84; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 61–62; Weintraub 1997, p. 232.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 232.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 71–105; Hobhouse 1983, pp. 26–43.

^ Lady Lyttelton's journal quoted in Fulford 1949, p. 95 and her correspondence quoted in Hobhouse 1983, p. 29.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 252; Weintraub 1997, p. 355.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 253–257; Weintraub 1997, p. 367.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 255.

^ Diary of Sir James Clark quoted in Fulford 1949, p. 256.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 260.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 261–262.

^ Magnus, Philip (1964) King Edward VII, pp. 19–20, quoted in Hobhouse 1983, pp. 28–29.

^ Stewart 2012, p. 182.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 392–393.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 150–151; Weintraub 1997, p. 401.

^ Stewart 2012, p. 198.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 404.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 405.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 152; Weintraub 1997, p. 406.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 406.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 154; Fulford 1949, p. 266.

^ Stewart 2012, p. 203.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 154–155; Martin & 1874–80, pp. 418–426, vol. V; Weintraub 1997, pp. 408–424.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, p. 3; Hobhouse 1983, p. 156 and Weintraub 1997, pp. 425–431.

^ Paulley, J.W. (1993). "The death of Albert Prince Consort: the case against typhoid fever". QJM. 86 (12): 837–841. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a068768. PMID 8108541.

^ e.g. Hobhouse 1983, pp. 150–151.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, p. 1; Hobhouse 1983, p. 158; Weintraub 1997, p. 436.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, pp. 1–4; Weintraub 1997, p. 436.

^ Weintraub 1997, p. 438.

^ Weintraub 1997, pp. 441–443.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. 57–58, 276; Hobhouse 1983, pp. viii, 39.

^ Fulford 1949, p. 67; Hobhouse 1983, p. 34.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, p. 21; Hobhouse 1983, p. 158

^ Darby & Smith 1983, p. 28; Hobhouse 1983, p. 162.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, p. 25.

^ Darby & Smith 1983, pp. 2, 6, 58–84.

^ Charles Dickens to John Leech, quoted in Darby & Smith 1983, p. 102 and Hobhouse 1983, p. 169.

^ Hobhouse 1983, pp. 48–49.

^ Hobhouse 1983, p. 53.

^ Fulford 1949, pp. ix–x.

^ e.g. Fulford 1949, pp. 22–23, 44, 104, 167, 209, 240.

^ Armstrong 2008.

^ Jurgensen 2009.

^ Knight 2009.

^ Weir 1996, p. 305.

^ abc Burke's Peerage & Baronetage, 1921, p. 3.

^ Nicolas, Sir Nicholas Harris (1842). History of the Orders of Knighthood of the British Empire; of the Order of the Guelphs and of the Medals, Clasps, and Crosses Conferred for the Naval and Military Services. 3. London: John Hunter. p. 190. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

^ "No. 20737". The London Gazette. 25 May 1847. p. 1950.

^ "No. 22523". The London Gazette. 25 June 1861. p. 2622.

^ H. Tarlier (1854). Almanach royal officiel, publié, exécution d'un arrête du roi (in French). 1. p. 37.

^ "Badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece". Royal Collection. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

^ Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 470. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

^ "A Szent István Rend tagjai". 22 December 2010.

^ "No. 21851". The London Gazette. 19 February 1856. p. 624.

^ Louda & Maclagan 1999, pp. 30, 32.

^ abc Pinches & Pinches 1974, pp. 329, 241, 309–310.

^ Aveling & Boutell 1890, p. 285.

^ Weir 1996, pp. 306–321.

^ abcdefgh Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh (ed.) (1977). Burke's Royal Families of the World, 1st edition. London: Burke's Peerage

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstu Huberty, M., Giraud, A., Magdelaine, F. & B. (1976–1994). L'Allemagne Dynastique, Vols I-VII. Le Perreux, France: Alain Giraud

^ Paget, Gerald (1977). The Lineage & Ancestry of HRH Prince Charles, Prince of Wales. Edinburgh & London: Charles Skilton

Sources

Abecasis-Phillips, John (2004). "Prince Albert and the Church – Royal versus Papal Supremacy in the Hampden Controversy". In Davis, John. Prinz Albert – Ein Wettiner in Großbritannien / Prince Albert – A Wettin in Great Britain. Munich: de Gruyter. pp. 95–110. ISBN 978-3-598-21422-6.

Ames, Winslow (1968). Prince Albert and Victorian Taste. London: Chapman and Hall.

Armstrong, Neil (2008). "England and German Christmas Festlichkeit, c. 1800–1914". German History. 26 (4): 486–503. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghn047.

Aveling, S. T.; Boutell, Charles (1890). Heraldry, Ancient and Modern: Including Boutell's Heraldry (2nd ed.). London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co.

Cust, Lionel (1907). "The Royal Collection of Pictures". The Cornhill Magazine, New Series. XXII: 162–170.

Darby, Elizabeth; Smith, Nicola (1983). The Cult of the Prince Consort. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03015-0.

Finestone, Jeffrey (1981). The Last Courts of Europe. London: The Vendome Press. ISBN 978-0-86565-015-2.

Fulford, Roger (1949). The Prince Consort. London: Macmillan Publishers.

Hobhouse, Hermione (1983). Prince Albert: His Life and Work. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-11142-0.

Jagow, Kurt, ed. (1938). The Letters of the Prince Consort, 1831–61. London: John Murray.

Jurgensen, John (4 December 2009). "Victorian Romance: When the dour queen was young and in love". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

Knight, Chris (17 December 2009). "A Duchess, a reader and a man named Alistair". National Post. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

Louda, Jiří; Maclagan, Michael (1999) [1981]. Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe (2nd ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-84820-6.

Martin, Theodore (1874–80). The Life of H. R. H. the Prince Consort. 5 volumes, authorised by Queen Victoria.

Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh, ed. (1977). Burke's Royal Families of the World (1st ed.). London: Burke's Peerage. ISBN 978-0-85011-023-4.

Murphy, James (2001). Abject Loyalty: Nationalism and Monarchy in Ireland During the Reign of Queen Victoria. Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1076-6.

Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974). Heraldry Today: The Royal Heraldry of England. Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press. ISBN 978-0-900455-25-4.

Stewart, Jules (2012). Albert: A Life. London; New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-977-7. OCLC 760284773.

Weintraub, Stanley (1997). Albert: Uncrowned King. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5756-9.

Weintraub, Stanley (September 2004). "Albert [Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha] (1819–1861)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online, January 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/274. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

(subscription required)

Weir, Alison (1996). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy (Revised ed.). London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-7126-7448-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert, Prince Consort. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Albert, Prince Consort |

Albert, Prince Consort at Encyclopædia Britannica

"Archival material relating to Albert, Prince Consort". UK National Archives.

Portraits of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at the Royal Collection

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albert (Francis Charles Augustus Albert Emmanuel)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 495–496.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albert (Francis Charles Augustus Albert Emmanuel)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 495–496.

Prince Consort Albert, England and Europe, Virtual exhibition of bavarikon

Prince Albert (1819–1861), BBC History

Albert, Prince Consort House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Cadet branch of the House of Wettin Born: 26 August 1819 Died: 14 December 1861 | ||

British royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

Vacant Title last held by Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen as queen consort | Consort of the British monarch (created "Prince Consort" 1857) 1840–1861 | Vacant Title next held by Alexandra of Denmark as queen consort |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Philip Philpot | Colonel of the 11th (Prince Albert's Own) Hussars 1840–1842 | Succeeded by Sir Arthur Benjamin Clifton |

| Preceded by The Earl Ludlow | Colonel of the Scots Fusilier Guards 1842–1852 | Succeeded by The Duke of Cambridge |

| Preceded by The Duke of Wellington | Colonel of the Grenadier Guards 1852–1861 | |

Colonel-in-Chief of the Rifle Brigade 1852–1861 | Succeeded by The Lord Seaton | |

| Court offices | ||

| Preceded by The Marquess of Hertford | Lord Warden of the Stannaries 1842–1861 | Succeeded by The Duke of Newcastle |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of Northumberland | Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1847–1861 | Succeeded by The Duke of Devonshire |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of Sussex | Great Master of the Order of the Bath 1847–1861 Acting 1843–1847 | Vacant Title next held by The Prince of Wales |