Russian alphabet

Russian alphabet in capital letters

The Russian alphabet (Russian: русский алфавит, tr. rússkij alfavít, IPA: [ˈruskʲɪj ɐɫfɐˈvʲit]) uses letters from the Cyrillic script to write the Russian language. The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters.

Contents

1 Table of the Russian alphabet

1.1 Frequency

2 Non-vocalized letters

2.1 Hard sign

2.2 Soft sign

3 Vowels

4 Letters in disuse by 1750

5 Letters eliminated in 1918

6 Treatment of foreign sounds

7 Numeric values

8 Diacritics

9 The Russian Keyboard

10 Letter names

11 See also

12 Notes

13 References

14 Bibliography

Table of the Russian alphabet

The Russian alphabet is as follows:

| Letter | Cursive | Italics | Name | Old name | IPA | Scientific transliteration | Approximate English equivalent | Examples | No. | Unicode (Hex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Аа | А а | а [a] | азъ [as] | /a/ | a | father | два dva "two" | 1 | U+0410 / U+0430 | |

Бб | Б б | бэ [bɛ] | буки [ˈbukʲɪ] | /b/ or /bʲ/ | b | bad | оба óba "both" | – | U+0411 / U+0431 | |

Вв | В в | вэ [vɛ] | вѣди [ˈvʲedʲɪ] | /v/ or /vʲ/ | v | vine | вот vot "here" | 2 | U+0412 / U+0432 | |

Гг | Г г | гэ [ɡɛ] | глаголь [ɡɫɐˈɡolʲ] | /ɡ/ or /gʲ/ | g | go | год god "year" | 3 | U+0413 / U+0433 | |

Дд | Д д | дэ [dɛ] | добро [dɐˈbro] | /d/ or /dʲ/ | d | do | да da "yes" | 4 | U+0414 / U+0434 | |

Ее | Е е | е [je] | есть [jesʲtʲ] | /je/, / ʲe/ or /e/ | e | yes | не ne "not" | 5 | U+0415 / U+0435 | |

Ёё | Ё ё | ё [jo] | – | /jo/ or / ʲo/ | ë | your | ёж yozh "hedgehog" | – | U+0401 / U+0451 | |

Жж | Ж ж | жэ [ʐɛ] ( | живѣте [ʐɨˈvʲetʲɪ][a] | /ʐ/ | ž | pleasure | жук zhuk "beetle" | – | U+0416 / U+0436 | |

Зз | З з | зэ [zɛ] | земля [zʲɪˈmlʲæ] | /z/ or /zʲ/ | z | zoo | зной znoy "heat" | 7 | U+0417 / U+0437 | |

Ии | И и | и [i] | иже [ˈiʐɨ] | /i/, / ʲi/, or /ɨ/ | i | police | или íli "or" | 8 | U+0418 / U+0438 | |

Йй | Й й | и краткое [i ˈkratkəjɪ] | и съ краткой [ɪ s ˈkratkəj] | /j/ | j | toy | мой moy "my, mine" | – | U+0419 / U+0439 | |

Кк | К к | ка [ka] | како [ˈkakə] | /k/ or /kʲ/ | k | kept | кто kto "who" | 20 | U+041A / U+043A | |

Лл† | Л л | эл or эль [ɛɫ] or [ɛlʲ] | люди [ˈlʲʉdʲɪ] | /ɫ/ or /lʲ/ | l | feel or lamp | ли li "whether" | 30 | U+041B / U+043B | |

Мм | М м | эм [ɛm] | мыслѣте [mɨˈsʲlʲetʲɪ][2] | /m/ or /mʲ/ | m | map | меч mech "sword" | 40 | U+041C / U+043C | |

Нн | Н н | эн [ɛn] | нашъ [naʂ] | /n/ or /nʲ/ | n | not | но no "but" | 50 | U+041D / U+043D | |

Оо | О о | о [о] | онъ [on] | /o/ | o | more | он on "he" | 70 | U+041E / U+043E | |

Пп | П п | пэ [pɛ] | покой [pɐˈkoj] | /p/ or /pʲ/ | p | pet | под pod "under" | 80 | U+041F / U+043F | |

Рр | Р р | эр [ɛr] | рцы [rtsɨ] | /r/ or /rʲ/ | r | rolled r | река reká "river" | 100 | U+0420 / U+0440 | |

Сс | С с | эс [ɛs] | слово [ˈsɫovə] | /s/ or /sʲ/ | s | set | если yésli "if" | 200 | U+0421 / U+0441 | |

Тт | Т т | тэ [tɛ] | твердо [ˈtvʲerdə] | /t/ or /tʲ/ | t | top | тот tot "that" | 300 | U+0422 / U+0442 | |

Уу | У у | у [u] | укъ [uk] | /u/ | u | tool | уже uzhé "already" | 400 | U+0423 / U+0443 | |

Фф | Ф ф | эф [ɛf] | фертъ [fʲert] | /f/ or /fʲ/ | f | face | форма fórma "form" | 500 | U+0424 / U+0444 | |

Хх | Х х | ха [xa] | хѣръ [xʲer] | /x/ or /xʲ/ | x | loch | дух dukh "spirit" | 600 | U+0425 / U+0445 | |

Цц | Ц ц | цэ [tsɛ] | цы [tsɨ] | /ts/ | c | sits | конец konéts "end" | 900 | U+0426 / U+0446 | |

Чч | Ч ч | че [tɕe] | червь [tɕerfʲ] | /tɕ/ | č | chat | час chas "hour" | 90 | U+0427 / U+0447 | |

Шш | Ш ш | ша [ʂa] | ша [ʂa] | /ʂ/ | š | sharp | ваш vash "yours" | – | U+0428 / U+0448 | |

Щщ | Щ щ | ща [ɕɕæ] | ща [ɕtɕæ] | /ɕɕ/ | šč | sheer (in some dialects pronounced as in pushchair) | щека shcheká "cheek" | – | U+0429 / U+0449 | |

Ъъ | Ъ ъ | твёрдый знак [ˈtvʲɵrdɨj znak ] ( | еръ [jer] | ʺ | (called "hard sign") silent, prevents palatalization of the preceding consonant | объект obyékt "object" | – | U+042A / U+044A | ||

Ыы | Ы ы | ы [ɨ] | еры [jɪˈrɨ] | [ɨ] | y | roses, hit | ты ty "you" | – | U+042B / U+044B | |

Ьь | Ь ь | мягкий знак [ˈmʲæxʲkʲɪj znak ] ( | ерь [jerʲ] | / ʲ/ | ' | (called "soft sign") silent, palatalizes the preceding consonant (if phonologically possible) | весь vyes' "all" | – | U+042C / U+044C | |

Ээ | Э э | э [ɛ] | э оборотное [ˈɛ ɐbɐˈrotnəjɪ] | /e/ | è | met | это éto "this, that" | – | U+042D / U+044D | |

Юю | Ю ю | ю [ju] | ю [ju] | /ju/ or / ʲu/ | ju | use | юг yug "south" | – | U+042E / U+044E | |

Яя | Я я | я [ja] | я [ja] | /ja/ or / ʲa/ | ja | yard | ряд ryad "row" | – | U+042F / U+044F | |

| Letters eliminated in 1917–18 | ||||||||||

| Letter | Cursive | Italics | Name | Old name | IPA | Scientific transliteration | Approximate English equivalent | Examples | No. | Unicode (Hex) |

Іі | – | І і | – | і десятеричное [i dʲɪsʲɪtʲɪˈrʲitɕnəjə] | /i/, / ʲi/, or /j/ | i | Like и or й | стихотворенія (now стихотворения) stikhotvoréniya "poems, (of) poem" | 10 | |

Ѳѳ | – | Ѳ ѳ | – | ѳита [fʲɪˈta] | /f/ or /fʲ/ | f | Like ф | орѳографія (now орфография) orfográfiya "orthography, spelling" | 9 | |

Ѣѣ | – | Ѣ ѣ | – | ять [jætʲ] | /e/ or / ʲe/ | ě | Like е | Алексѣй (now Алексей) Aleksěy Alexey | – | |

Ѵѵ | – | Ѵ ѵ | – | ижица [ˈiʐɨtsə] | /i/ or / ʲi/ | i | Usually like и, see below | мѵро (now миро) míro "chrism (myrrh)" | – | |

| Letters eliminated before 1750 | ||||||||||

| Letter | Cursive | Italics | Name | Old name | IPA | Scientific transliteration | Approximate English equivalent | Examples | No. | Unicode (Hex) |

Ѕѕ | – | Ѕ ѕ | – | зѣло [zʲɪˈɫo][3] | /z/ or /zʲ/ | z | Like з | sело (now очень) "very" | 6 | |

Ѯѯ | – | Ѯ ѯ | – | кси [ksʲi] | /ks/ or /ksʲ/ | ks | Like кс | N/A | 60 | |

Ѱѱ | – | Ѱ ѱ | – | пси [psʲi] | /ps/ or /psʲ/ | ps | Like пс | N/A | 700 | |

Ѡѡ | – | Ѡ ѡ | – | омега [ɐˈmʲeɡə] | /o/ | o | Like о | N/A | 800 | |

Ѫѫ | – | Ѫ ѫ | – | юсъ большой [jus bɐlʲˈʂoj] | /u/, /ju/ or / ʲu/ | ǫ | Like у or ю | N/A | – | |

Ѧѧ | – | Ѧ ѧ | – | юсъ малый [jus ˈmaɫɨj] | /ja/ or / ʲa/ | ę | Like я | N/A | – | |

Ѭѭ | – | Ѭ ѭ | – | юсъ большой іотированный [jus bɐlʲˈʂoj jɪˈtʲirəvənnɨj] | /ju/ or / ʲu/ | jǫ | Like ю | N/A | – | |

Ѩѩ | – | Ѩ ѩ | – | юсъ малый іотированный [jus ˈmaɫɨj jɪˈtʲirəvən.nɨj] | /ja/ or / ʲa/ | ję | Like я | N/A | – | |

| Letter | Cursive | Italics | Name | Old name | IPA | Scientific transliteration | Approximate English equivalent | Examples | No. | Unicode (Hex) |

Consonant letters represent both "soft" (palatalized, represented in the IPA with a ⟨ʲ⟩) and "hard" consonant phonemes. If consonant letters are followed by vowel letters, the soft/hard quality of the consonant depends on whether the vowel is meant to follow "hard" consonants ⟨а, о, э, у, ы⟩ or "soft" consonants ⟨я, ё, е, ю, и⟩; see below. A soft sign indicates ⟨Ь⟩ palatalization of the preceding consonant without adding a vowel. However, in modern Russian six consonant phonemes do not have phonemically distinct "soft" and "hard" variants (except in foreign proper names) and do not change "softness" in the presence of other letters: /ʐ/, /ʂ/ and /ts/ are always hard; /j/, /ɕː/ and /tɕ/ are always soft. See Russian phonology for details.

^† An alternate form of the letter El (Л л) closely resembles the Greek letter for lambda (Λ λ).

Frequency

The frequency of characters in a corpus of written Russian was found to be as follows:[4]

| Letter | Frequency | Other information |

|---|---|---|

О | 11.07% | The most frequently used letter in the Russian alphabet. |

Е | 8.50% | Foreign words sometimes use Е rather than Э, even if it is pronounced e instead of ye. In addition, Ё is often replaced by Е. This makes Е even more common. For more information, see Vowels. |

А | 7.50% | |

И | 7.09% | |

Н | 6.70% | The most common consonant in the Russian alphabet. |

Т | 5.97% | |

С | 4.97% | |

Л | 4.96% | |

В | 4.33% | |

Р | 4.33% | |

К | 3.30% | |

М | 3.10% | |

Д | 3.09% | |

П | 2.47% | |

Ы | 2.36% | |

У | 2.22% | |

Б | 2.01% | |

Я | 1.96% | |

Ь | 1.84% | |

Г | 1.72% | |

З | 1.48% | |

Ч | 1.40% | |

Й | 1.21% | |

Ж | 1.01% | |

Х | 0.95% | |

Ш | 0.72% | |

Ю | 0.47% | |

Ц | 0.39% | |

Э | 0.36% | Foreign words sometimes use E rather than Э, even if it is pronounced e instead of ye. This makes Э even less common. For more information, see Vowels. |

Щ | 0.30% | |

Ф | 0.21% | The least common consonant in the Russian alphabet. |

Ё | 0.20% | In written Russian, Ё is often replaced by E. For more information, see Vowels. |

Ъ | 0.02% | Ъ used to be a very common letter in the Russian alphabet. This is because before the 1918 reform, any word ending with a non-palatalized consonant was written with a final Ъ - e.g., pre-1918 вотъ vs. post-reform вот. The reform eliminated the use of Ъ in this context, leaving it the least common letter in the Russian alphabet. For more information, see Non-vocalized letters. |

Non-vocalized letters

Hard sign

The hard sign (⟨ъ⟩) acts like a "silent back vowel" that separates a succeeding "soft vowel" (е, ё, ю, я, but not и) from a preceding consonant, invoking implicit iotation of the vowel with a distinct /j/ glide. Today it is used mostly to separate a prefix ending with a hard consonant from the following root. Its original pronunciation, lost by 1400 at the latest, was that of a very short middle schwa-like sound, /ŭ/ but likely pronounced [ə] or [ɯ]. Until the 1918 reform, no written word could end in a consonant: those that end in a ("hard") consonant in modern orthography had then a final ъ.

While ⟨и⟩ is also a soft vowel, root-initial /i/ following a hard consonant is typically pronounced as [ɨ]. This is normally spelled ⟨ы⟩ (the hard counterpart to ⟨и⟩) unless this vowel occurs at the beginning of a word, in which case it remains ⟨и⟩. An alternation between the two letters (but not the sounds) can be seen with the pair без и́мени ('without name', which is pronounced [bʲɪz ˈɨmʲɪnʲɪ]) and безымя́нный ('nameless', which is pronounced [bʲɪzɨˈmʲænːɨj]). This spelling convention, however, is not applied with certain loaned prefixes such as in the word панислами́зм – [ˌpanɨsɫɐˈmʲizm], 'Pan-Islamism') and compound (multi-root) words (e.g. госизме́на – [ˌɡosɨˈzmʲenə], 'high treason').

Soft sign

The soft sign (⟨ь⟩) in most positions acts like a "silent front vowel" and indicates that the preceding consonant is palatalized (except for always-hard ж, ш, ц) and the following vowel (if present) is iotated (including ьо in loans). This is important as palatalization is phonemic in Russian. For example, брат [brat] ('brother') contrasts with брать [bratʲ] ('to take'). The original pronunciation of the soft sign, lost by 1400 at the latest, was that of a very short fronted reduced vowel /ĭ/ but likely pronounced [ɪ] or [jɪ]. There are still some remnants of this ancient reading in modern Russian, e.g. in the co-existing versions of the same name, read and written differently, such as Марья and Мария (Mary).[5]

When applied after stem-final always-soft (ч, щ, but not й) or always-hard (ж, ш, but not ц) consonants, the soft sign does not alter pronunciation, but has a grammatical meaning:[6]

- feminine gender for singular nouns in nominative and accusative cases; e.g. тушь ('India ink', feminine) cf. туш ('flourish after a toast', masculine) – both pronounced [tuʂ];

- imperative mood for some verbs;

- infinitive form of some verbs (with -чь ending);

- second person for non-past verbs (with -шь ending);

- some adverbs and particles.

Vowels

The vowels ⟨е, ё, и, ю, я⟩ indicate a preceding palatalized consonant and with the exception of ⟨и⟩ are iotated (pronounced with a preceding /j/) when written at the beginning of a word or following another vowel (initial ⟨и⟩ was iotated until the nineteenth century). The IPA vowels shown are a guideline only and sometimes are realized as different sounds, particularly when unstressed. However, ⟨е⟩ may be used in words of foreign origin without palatalization (/e/), and ⟨я⟩ is often realized as [æ] between soft consonants, such as in мяч ("toy ball").

⟨ы⟩ is an old Proto-Slavic close central vowel, thought to have been preserved better in modern Russian than in other Slavic languages. It was originally nasalized in certain positions: камы [ˈkamɨ̃]; камень [ˈkamʲɪnʲ] ("rock"). Its written form developed as follows: ⟨ъ⟩ + ⟨і⟩ → ⟨ꙑ⟩ → ⟨ы⟩.

⟨э⟩ was introduced in 1708 to distinguish the non-iotated/non-palatalizing /e/ from the iotated/palatalizing one. The original usage had been ⟨е⟩ for the uniotated /e/, ⟨ѥ⟩ or ⟨ѣ⟩ for the iotated, but ⟨ѥ⟩ had dropped out of use by the sixteenth century. In native Russian words, ⟨э⟩ is found only at the beginnings of words or in compound words (e.g. поэтому "therefore" = по + этому). In words that come from foreign languages in which iotated /e/ is uncommon or nonexistent (such as English, for example), ⟨э⟩ is usually written in the beginning of words and after vowels except ⟨и⟩ (e.g. поэт, poet), and ⟨е⟩ after ⟨и⟩ and consonants. However, the pronunciation is inconsistent. Many words, especially monosyllables, words ending in ⟨е⟩ and many words where ⟨е⟩ follows ⟨т⟩, ⟨д⟩, ⟨н⟩, ⟨с⟩, ⟨з⟩ or ⟨р⟩ are pronounced with /e/ without palatalization or iotation: секс (seks — "sex"), проект (proekt — "project") (in this example, the spelling is etymological but the pronunciation is counteretymological). But many other words are pronounced with /ʲe/: секта (syekta — "sect"), дебют (dyebyut — "debut"). Proper names are usually not concerned by the rule (Сэм — "Sam", Пэмела — "Pamela", Мао Цзэдун — "Mao Zedong"); the use of ⟨э⟩ after consonants is common in East Asian names and in English names with the sounds /æ/ and /ɛər/, with some exceptions such as Джек ("Jack") or Шепард ("Shepard"), since both ⟨э⟩ and ⟨е⟩ are following always hard (non-palatalized) consonants in cases of же ("zhe"), ше ("she") and це ("tse"), yet in writing ⟨е⟩ usually prevails.

⟨ё⟩, introduced by Karamzin in 1797 and made official in 1943 by the Soviet Ministry of Education,[7] marks a /jo/ sound that has historically developed from /je/ under stress, a process that continues today. The letter ⟨ё⟩ is optional (in writing, not in pronunciation): it is formally correct to write ⟨e⟩ for both /je/ and /jo/. None of the several attempts in the twentieth century to mandate the use of ⟨ё⟩ have stuck.

Letters in disuse by 1750

⟨ѯ⟩ and ⟨ѱ⟩ derived from Greek letters xi and psi, used etymologically though inconsistently in secular writing until the eighteenth century, and more consistently to the present day in Church Slavonic.

⟨ѡ⟩ is the Greek letter omega, identical in pronunciation to ⟨о⟩, used in secular writing until the eighteenth century, but to the present day in Church Slavonic, mostly to distinguish inflexional forms otherwise written identically.

⟨ѕ⟩ corresponded to a more archaic /dz/ pronunciation, already absent in East Slavic at the start of the historical period, but kept by tradition in certain words until the eighteenth century in secular writing, and in Church Slavonic and Macedonian to the present day.

The yuses ⟨ѫ⟩ and ⟨ѧ⟩, letters that originally used to stand for nasalized vowels /õ/ and /ẽ/, had become, according to linguistic reconstruction, irrelevant for East Slavic phonology already at the beginning of the historical period, but were introduced along with the rest of the Cyrillic script. The letters ⟨ѭ⟩ and ⟨ѩ⟩ had largely vanished by the twelfth century. The uniotated ⟨ѫ⟩ continued to be used, etymologically, until the sixteenth century. Thereafter it was restricted to being a dominical letter in the Paschal tables. The seventeenth-century usage of ⟨ѫ⟩ and ⟨ѧ⟩ (see next note) survives in contemporary Church Slavonic, and the sounds (but not the letters) in Polish.

The letter ⟨ѧ⟩ was adapted to represent the iotated /ja/ ⟨я⟩ in the middle or end of a word; the modern letter ⟨я⟩ is an adaptation of its cursive form of the seventeenth century, enshrined by the typographical reform of 1708.

Until 1708, the iotated /ja/ was written ⟨ıa⟩ at the beginning of a word. This distinction between ⟨ѧ⟩ and ⟨ıa⟩ survives in Church Slavonic.

Although it is usually stated that the letters labelled "fallen into disuse by the eighteenth century" in the table above were eliminated in the typographical reform of 1708, reality is somewhat more complex. The letters were indeed originally omitted from the sample alphabet, printed in a western-style serif font, presented in Peter's edict, along with the letters ⟨з⟩ (replaced by ⟨ѕ⟩), ⟨и⟩, and ⟨ф⟩ (the diacriticized letter ⟨й⟩ was also removed), but were reinstated except ⟨ѱ⟩ and ⟨ѡ⟩ under pressure from the Russian Orthodox Church in a later variant of the modern typeface (1710). Nonetheless, since 1735 the Russian Academy of Sciences began to use fonts without ⟨ѕ⟩, ⟨ѯ⟩, and ⟨ѵ⟩; however, ⟨ѵ⟩ was sometimes used again since 1758.

Letters eliminated in 1918

| Grapheme | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

і | Decimal I | Identical in pronunciation to ⟨и⟩, was used exclusively immediately in front of other vowels and the ⟨й⟩ ("Short I") (for example, ⟨патріархъ⟩ [pətrʲɪˈarx], 'patriarch') and in the word ⟨міръ⟩ [mʲir] ('world') and its derivatives, to distinguish it from the word ⟨миръ⟩ [mʲir] ('peace') (the two words are actually etymologically cognate[8][9] and not arbitrarily homonyms).[10] |

| ѳ | Fita | From the Greek theta, was identical to ⟨ф⟩ in pronunciation, but was used etymologically (for example, ⟨Ѳёдоръ⟩ "Theodore" became ⟨Фёдор⟩ "Fyodor"). |

| ѣ | Yat | Originally had a distinct sound, but by the middle of the eighteenth century had become identical in pronunciation to ⟨е⟩ in the standard language. Since its elimination in 1918, it has remained a political symbol of the old orthography. |

| ѵ | Izhitsa | From the Greek upsilon, usually identical to ⟨и⟩ in pronunciation, as in Byzantine Greek, was used etymologically for Greek loanwords, like Latin Y (as in synod, myrrh); by 1918, it had become very rare. In spellings of the eighteenth century, it was also used after some vowels, where it has since been replaced with ⟨в⟩ or (rarely) ⟨у⟩. For example, a Greek prefix originally spelled ⟨аѵто-⟩ (equivalent to English auto-) is now spelled ⟨авто⟩ in most cases and ⟨ауто-⟩ as a component in some compound words. |

Treatment of foreign sounds

Because Russian borrows terms from other languages, there are various conventions for sounds not present in Russian.

For example, while Russian has no [h], there are a number of common words (particularly proper nouns) borrowed from languages like English and German that contain such a sound in the original language. In well-established terms, such as галлюцинация [ɡəlʲutsɨˈnatsɨjə] ('hallucination'), this is written with ⟨г⟩ and pronounced with /ɡ/, while newer terms use ⟨х⟩, pronounced with /x/, such as хобби [ˈxobʲɪ] ('hobby').[11]

Similarly, words originally with [θ] in their source language are either pronounced with /t(ʲ)/), as in the name Тельма ('Thelma') or, if borrowed early enough, with /f(ʲ)/ or /v(ʲ)/, as in the names Фёдор ('Theodore') and Матве́й ('Matthew').

For the [d͡ʒ] affricate, which is common in the Asian countries that were parts of the Russian Empire and USSR, the letter combination ⟨дж⟩ is used: this is often transliterated into English either as ⟨dzh⟩ or the Dutch form ⟨dj⟩.

Numeric values

The numerical values correspond to the Greek numerals, with ⟨ѕ⟩ being used for digamma, ⟨ч⟩ for koppa, and ⟨ц⟩ for sampi. The system was abandoned for secular purposes in 1708, after a transitional period of a century or so; it continues to be used in Church Slavonic, while general Russian texts use Hindu-Arabic numerals and Roman numerals.

Diacritics

Russian spelling uses fewer diacritics than those used for most European languages. The only diacritic, in the proper sense, is the acute accent ⟨◌́⟩ (Russian: знак ударения 'mark of stress'), which marks stress on a vowel, as it is done in Spanish and Greek. Although Russian word stress is often unpredictable and can fall on different syllables in different forms of the same word, the diacritic is used only in dictionaries, children's books, resources for foreign-language learners, the defining entry (in bold) in articles on the Russian Wikipedia, or on minimal pairs distinguished only by stress (for instance, за́мок 'castle' vs. замо́к 'lock'). Rarely, it is used to specify the stress in uncommon foreign words and in poems with unusual stress used to fit the meter. Unicode has no code points for the accented letters; they are instead produced by suffixing the unaccented letter with .mw-parser-output .monospaced{font-family:monospace,monospace}

U+0301 ◌́ .mw-parser-output .smallcaps{font-variant:small-caps}COMBINING ACUTE ACCENT.

The letter ⟨ё⟩ is a special variant of the letter ⟨е⟩, which is not always distinguished in written Russian, but the umlaut-like sign has no other uses. Stress on this letter is never marked, as it is always stressed except in some loanwords.

Unlike the case of ⟨ё⟩, the letter ⟨й⟩ has completely separated from ⟨и⟩. It has been used since the 16th century except that it was removed in 1708 but reinstated in 1735. Since then, its usage has been mandatory. It was formerly considered a diacriticized letter, but in the 20th century, it came to be considered a separate letter of the Russian alphabet. It was classified as a "semivowel" by 19th- and 20th-century grammarians but since the 1970s, it has been considered a consonant letter.

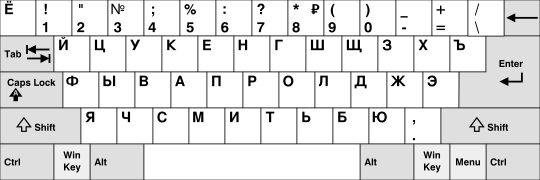

The Russian Keyboard

The standard Russian keyboard layout for personal computers is as follows:

However, there are several choices of so-called "phonetic keyboards" that one may use on a PC that are often used by non-Russians. For example, typing an English (Latin) letter on a keyboard will actually type a Russian letter with a similar sound (A=А, S=С, D=Д, F=Ф, etc.).

Letter names

Until approximately the year 1900, mnemonic names inherited from Church Slavonic were used for the letters. They are given here in the pre-1918 orthography of the post-1708 civil alphabet.

The great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin wrote: "The letters constituting the Slavonic alphabet do not produce any sense. Аз, буки, веди, глаголь, добро etc. are separate words, chosen just for their initial sound". However, since the names of the first letters of the Slavonic alphabet seem to form text, attempts were made to compose sensible text from all letters of the alphabet.[12][13]

Here is one such attempt to "decode" the message:

| аз буки веди | az buki vedi | I know letters[14] |

| глаголь добро есть | glagol' dobro yest' | "To speak is a beneficence" or "The word is property"[15] |

| живете зело, земля, и иже и како люди | zhivyete zelo, zyemlya, i izhe, i kako lyudi | "Live, while working heartily, people of Earth, in the manner people should obey" |

| мыслете наш он покой | myslete nash on pokoy | "try to understand the Universe (the world that is around)" |

| рцы слово твердо | rtsy slovo tvyerdo | "be committed to your word"[16] |

| ук ферт хер | uk fert kher | "The knowledge is fertilized by the Creator, knowledge is the gift of God" |

| цы червь ша ер ять ю | tsy cherv' sha yet yat' yu | "Try harder, to understand the Light of the Creator" |

In this attempt only lines 1, 2 and 5 somewhat correspond to real meanings of the letters' names, while "translations" in other lines seem to be fabrications or fantasies. For example, "покой" ("rest" or "apartment") does not mean "the Universe", and "ферт" does not have any meaning in Russian or other Slavic languages (there are no words of Slavic origin beginning with "f" at all). The last line contains only one translatable word – "червь" ("worm"), which, however, was not included in the "translation".

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russian alphabet. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Introduction of the civil Russian alphabet by Peter I. |

- Bulgarian alphabet

- Computer russification

- Cyrillic alphabets

- Cyrillic script

- Euro-Ukrainian alphabet

- Greek alphabet

- Montenegrin alphabet

- Reforms of Russian orthography

- Romanization of Belarusian

- Romanization of Bulgarian

- Romanization of Greek

- Romanization of Macedonian

- Romanization of Russian

- Romanization of Ukrainian

- Russian Braille

Russian cursive (handwritten letters)- Russian manual alphabet

- Russian orthography

- Russian phonology

- Scientific transliteration of Cyrillic

- Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

- Yoficator

Notes

^ Ushakov, Dmitry, "живете", Толковый словарь русского языка Ушакова [Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language] (article) (in Russian), RU: Yandex, archived from the original on 2012-07-22.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}; the dictionary makes difference between е and ё.[1]

References

^ Ushakov, Dmitry, "ёлка", Толковый словарь русского языка Ушакова (in Russian), RU: Yandex, archived from the original on 2012-07-22.

^ Ushakov, Dmitry, "мыслете", Толковый словарь русского языка Ушакова [Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language] (article) (in Russian), RU: Yandex, archived from the original on 2012-07-16.

^ ФЭБ, feb-web.ru

^ Stefan Trost Media, Character Frequency: Russian. "Basis of this list were some Russian texts with together 1.351.370 characters (210.844 words), 1.086.255 characters were used for the counting. The texts consist of a good mix of different literary genres."

^ See Polish Maria as a given name but Maryja in context of the Virgin Mary.

^ "Буквы Ъ и Ь - "Грамота.ру" – справочно-информационный Интернет-портал "Русский язык"". gramota.ru. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

^ Benson 1960, p. 271.

^ Vasmer 1979.

^ Vasmer, "мир", Dictionary (etymology) (in Russian) (online ed.), retrieved 16 October 2005.

^ Smirnovskiy 1915, p. 4.

^ Dunn & Khairov 2009, pp. 17–8.

^ Maksimovic M.A. (1839). История древней русской словесности. Киев: Университетская типография. p. 215.

^ Pavskij G.P. (1850). Филологическия наблюдения над составом русскаго языка: О буквах и слогах. Первое разсуждение. p. 35.

^ Р. Байбурова (2002). Как появилась письменность у древних славян (in Russian). Наука и Жизнь. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

^ Vasilʹev A. (1838). О древнейшей истории северных славян до времён Рюрика. Главный штаб Его Императорского Величества по военно-учебным заведениям. p. 159.

^ Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка. 4. ОЛМА Медиа Групп. p. 91. ISBN 9785224024384.

Bibliography

- Ivan G. Iliev. Kurze Geschichte des kyrillischen Alphabets. Plovdiv. 2015. [1]

- Ivan G. Iliev. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet. [2]

Benson, Morton (1960), "Review of The Russian Alphabet by Thomas F. Magner", The Slavic and East European Journal, 4 (3): 271–72, doi:10.2307/304189

Dunn, John; Khairov, Shamil (2009), Modern Russian Grammar, Modern Grammars, Routledge

Halle, Morris (1959), Sound Pattern of Russian, MIT Press

Smirnovskiy, P (1915), A Textbook in Russian Grammar, Part I. Etymology (26th ed.), CA: Shaw

Vasmer, Max (1979), Russian Etymological Dictionary, Winter