Amelia Earhart

This article uses HTML markup. (February 2019) |

Amelia Earhart | |

|---|---|

Earhart beneath the nose of her Lockheed Model 10-E Electra, March 1937, Oakland, California | |

| Born | Amelia Mary Earhart (1897-07-24)July 24, 1897 Atchison, Kansas, U.S. |

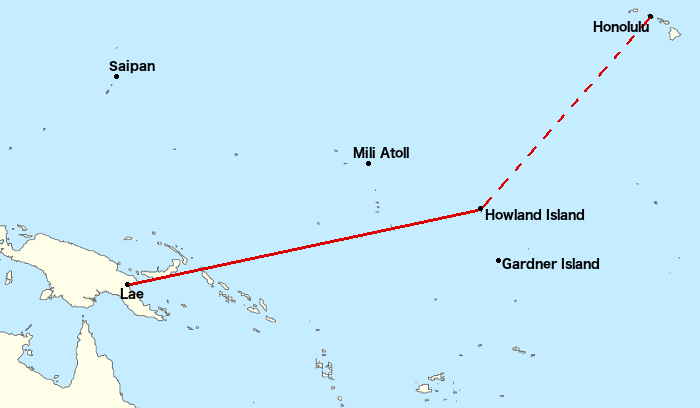

| Disappeared | July 2, 1937 (aged 39) Pacific Ocean, en route to Howland Island from Lae, Papua New Guinea |

| Status | Declared dead in absentia January 5, 1939(1939-01-05) (aged 41) |

| Known for | Many early aviation records, including first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean |

| Spouse(s) | George P. Putnam (m. 1931) |

| Website | Official website |

| Signature | |

Amelia Mary Earhart (/ˈɛərhɑːrt/, born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937) was an American aviation pioneer and author.[1][Note 1] Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.[3][Note 2] She received the United States Distinguished Flying Cross for this accomplishment.[5] She set many other records,[2] wrote best-selling books about her flying experiences and was instrumental in the formation of The Ninety-Nines, an organization for female pilots.[6] In 1935, Earhart became a visiting faculty member at Purdue University as an advisor to aeronautical engineering and a career counselor to women students. She was also a member of the National Woman's Party and an early supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment.[7][8]

During an attempt to make a circumnavigational flight of the globe in 1937 in a Purdue-funded Lockheed Model 10-E Electra, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan disappeared over the central Pacific Ocean near Howland Island. Fascination with her life, career, and disappearance continues to this day.[Note 3]

Contents

1 Early life

1.1 Childhood

1.2 Early influence

1.3 Education

1.4 Family fortunes

1.5 Spanish flu pandemic of 1918

1.6 Early flying experiences

2 Aviation career and marriage

2.1 Financial crisis

2.2 Boston

2.3 Transatlantic flight in 1928

2.4 Celebrity image

2.5 Promoting aviation

2.6 Competitive flying

2.7 Marriage to George Putnam

3 Transatlantic solo flight in 1932

3.1 Additional solo flights

4 Move from New York to California

5 World flight in 1937

5.1 Planning

5.2 First attempt

5.3 Second attempt

5.4 Departure from Lae

5.5 Radio equipment

5.6 Nearing Howland Island

5.7 Radio signals

5.8 Search efforts

6 Speculation on disappearance

6.1 Crash and sink theory

6.2 Gardner Island hypothesis

6.3 Japanese capture theory

6.4 Myths, legends, and claims

6.4.1 Spies for FDR

6.4.2 Tokyo Rose

6.4.3 New Britain

6.4.4 Assuming another identity

7 Legacy

7.1 Memorial flights

7.2 Other honors

8 In popular culture

9 Records and achievements

10 Books by Earhart

11 See also

12 References

12.1 Notes

12.2 Citations

12.3 Bibliography of cited sources

13 Further reading

14 External links

Early life

Childhood

Earhart as a child

Earhart was the daughter of Samuel "Edwin" Stanton Earhart (1867–1930) and Amelia "Amy" (née Otis; 1869–1962).[10] She was born in Atchison, Kansas, in the home of her maternal grandfather, Alfred Gideon Otis (1827–1912), who was a former federal judge, the president of the Atchison Savings Bank and a leading citizen in the town. Amelia was the second child of the marriage, after an infant was stillborn in August 1896.[11] She was of part German descent. Alfred Otis had not initially favored the marriage and was not satisfied with Edwin's progress as a lawyer.[12]

According to family custom, Earhart was named after her two grandmothers, Amelia Josephine Harres and Mary Wells Patton.[11] From an early age, Amelia was the ringleader while her sister Grace Muriel Earhart (1899–1998), two years her junior, acted as the dutiful follower.[13] Amelia was nicknamed "Meeley" (sometimes "Millie") and Grace was nicknamed "Pidge"; both girls continued to answer to their childhood nicknames well into adulthood.[11] Their upbringing was unconventional since Amy Earhart did not believe in molding her children into "nice little girls".[14] Meanwhile their maternal grandmother disapproved of the "bloomers" worn by Amy's children and although Earhart liked the freedom they provided, she was aware other girls in the neighborhood did not wear them.

Early influence

1963 U.S. Postal stamp honoring Earhart

A spirit of adventure seemed to abide in the Earhart children, with the pair setting off daily to explore their neighborhood.[Note 4] As a child, Earhart spent long hours playing with sister Pidge, climbing trees, hunting rats with a rifle and "belly-slamming" her sled downhill.[16] Although the love of the outdoors and "rough-and-tumble" play was common to many youngsters, some biographers have characterized the young Earhart as a tomboy.[17] The girls kept "worms, moths, katydids and a tree toad"[18] in a growing collection gathered in their outings. In 1904, with the help of her uncle, she cobbled together a home-made ramp fashioned after a roller coaster she had seen on a trip to St. Louis and secured the ramp to the roof of the family toolshed. Earhart's well-documented first flight ended dramatically. She emerged from the broken wooden box that had served as a sled with a bruised lip, torn dress and a "sensation of exhilaration". She exclaimed, "Oh, Pidge, it's just like flying!"[12]

Although there had been some missteps in Edwin Earhart's career up to that point, in 1907 his job as a claims officer for the Rock Island Railroad led to a transfer to Des Moines, Iowa. The next year, at the age of 10,[19] Earhart saw her first aircraft at the Iowa State Fair in Des Moines.[20][21] Her father tried to interest her and her sister in taking a flight. One look at the rickety "flivver" was enough for Earhart, who promptly asked if they could go back to the merry-go-round.[22] She later described the biplane as "a thing of rusty wire and wood and not at all interesting".[23]

Education

The two sisters, Amelia and Muriel (she went by her middle name from her teens on), remained with their grandparents in Atchison, while their parents moved into new, smaller quarters in Des Moines. During this period, Earhart received a form of home-schooling together with her sister, from her mother and a governess. She later recounted that she was "exceedingly fond of reading"[24] and spent countless hours in the large family library. In 1909, when the family was finally reunited in Des Moines, the Earhart children were enrolled in public school for the first time with Amelia Earhart entering the seventh grade at the age of 12 years.

Family fortunes

Earhart in evening clothes

While the family's finances seemingly improved with the acquisition of a new house and even the hiring of two servants, it soon became apparent that Edwin was an alcoholic. Five years later in 1914, he was forced to retire and although he attempted to rehabilitate himself through treatment, he was never reinstated at the Rock Island Railroad. At about this time, Earhart's grandmother Amelia Otis died suddenly, leaving a substantial estate that placed her daughter's share in a trust, fearing that Edwin's drinking would drain the funds. The Otis house was auctioned along with all of its contents; Earhart was heartbroken and later described it as the end of her childhood.[25]

In 1915, after a long search, Earhart's father found work as a clerk at the Great Northern Railway in St. Paul, Minnesota, where Earhart entered Central High School as a junior. Edwin applied for a transfer to Springfield, Missouri, in 1915 but the current claims officer reconsidered his retirement and demanded his job back, leaving the elder Earhart with nowhere to go. Facing another calamitous move, Amy Earhart took her children to Chicago, where they lived with friends. Earhart made an unusual condition in the choice of her next schooling; she canvassed nearby high schools in Chicago to find the best science program. She rejected the high school nearest her home when she complained that the chemistry lab was "just like a kitchen sink".[26] She eventually enrolled in Hyde Park High School but spent a miserable semester where a yearbook caption captured the essence of her unhappiness, "A.E. – the girl in brown who walks alone".[27]

Earhart graduated from Chicago's Hyde Park High School in 1916.[28] Throughout her troubled childhood, she had continued to aspire to a future career; she kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about successful women in predominantly male-oriented fields, including film direction and production, law, advertising, management and mechanical engineering.[19] She began junior college at Ogontz School in Rydal, Pennsylvania, but did not complete her program.[29][Note 5][30]

During Christmas vacation in 1917, Earhart visited her sister in Toronto. World War I had been raging and Earhart saw the returning wounded soldiers. After receiving training as a nurse's aide from the Red Cross, she began work with the Voluntary Aid Detachment at Spadina Military Hospital. Her duties included preparing food in the kitchen for patients with special diets and handing out prescribed medication in the hospital's dispensary.[31][32]

Spanish flu pandemic of 1918

When the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic reached Toronto, Earhart was engaged in arduous nursing duties that included night shifts at the Spadina Military Hospital.[33][34] She became a patient herself, suffering from pneumonia and maxillary sinusitis.[33] She was hospitalized in early November 1918, owing to pneumonia, and discharged in December 1918, about two months after the illness had started.[33] Her sinus-related symptoms were pain and pressure around one eye and copious mucus drainage via the nostrils and throat.[35] While staying in the hospital during the pre-antibiotic era, she had painful minor operations to wash out the affected maxillary sinus,[33][34][35] but these procedures were not successful and Earhart subsequently suffered from worsening headaches. Her convalescence lasted nearly a year, which she spent at her sister's home in Northampton, Massachusetts.[34] She passed the time by reading poetry, learning to play the banjo and studying mechanics.[33] Chronic sinusitis significantly affected Earhart's flying and activities in later life,[35] and sometimes even on the airfield she was forced to wear a bandage on her cheek to cover a small drainage tube.[36]

Early flying experiences

At about that time, Earhart and a young woman friend visited an air fair held in conjunction with the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. One of the highlights of the day was a flying exhibition put on by a World War I ace.[37] The pilot overhead spotted Earhart and her friend, who were watching from an isolated clearing, and dived at them. "I am sure he said to himself, 'Watch me make them scamper,'" she said. Earhart stood her ground as the aircraft came close. "I did not understand it at the time," she said, "but I believe that little red airplane said something to me as it swished by."[38]

By 1919 Earhart prepared to enter Smith College but changed her mind and enrolled at Columbia University, in a course in medical studies among other programs.[39] She quit a year later to be with her parents, who had reunited in California.

Neta Snook and Amelia Earhart in front of Earhart's Kinner Airster, c. 1921

In Long Beach, on December 28, 1920, Earhart and her father visited an airfield where Frank Hawks (who later gained fame as an air racer) gave her a ride that would forever change Earhart's life. "By the time I had got two or three hundred feet [60–90 m] off the ground," she said, "I knew I had to fly."[40] After that 10-minute flight (which cost her father $10), she immediately determined to learn to fly. Working at a variety of jobs including photographer, truck driver, and stenographer at the local telephone company, she managed to save $1,000 for flying lessons. Earhart had her first lesson on January 3, 1921, at Kinner Field near Long Beach. Her teacher was Anita "Neta" Snook, a pioneer female aviator who used a surplus Curtiss JN-4 "Canuck" for training. Earhart arrived with her father and a singular request: "I want to fly. Will you teach me?"[41] In order to reach the airfield, Earhart had to take a bus to the end of the line, then walk four miles (6 km). Earhart's mother also provided part of the $1,000 "stake" against her "better judgement".[42]

Earhart's commitment to flying required her to accept the frequent hard work and rudimentary conditions that accompanied early aviation training. She chose a leather jacket, but aware that other aviators would be judging her, she slept in it for three nights to give the jacket a "worn" look. To complete her image transformation, she also cropped her hair short in the style of other female flyers.[43] Six months later, Earhart purchased a secondhand bright yellow Kinner Airster biplane she nicknamed "The Canary". On October 22, 1922, Earhart flew the Airster to an altitude of 14,000 feet (4,300 m), setting a world record for female pilots. On May 15, 1923, Earhart became the 16th woman in the United States to be issued a pilot's license (#6017)[44] by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI).[45][46][Note 6]

Aviation career and marriage

Amelia Earhart, Los Angeles, 1928

X5665 – 1926 "CIT-9 Safety Plane"

Financial crisis

Throughout the early 1920s, following a disastrous investment in a failed gypsum mine, Earhart's inheritance from her grandmother, which was now administered by her mother, steadily diminished until it was exhausted. Consequently, with no immediate prospects for recouping her investment in flying, Earhart sold the "Canary" as well as a second Kinner and bought a yellow Kissel "Speedster" two-passenger automobile, which she named the "Yellow Peril". Simultaneously, Earhart experienced an exacerbation of her old sinus problem as her pain worsened and in early 1924 she was hospitalized for another sinus operation, which was again unsuccessful. After trying her hand at a number of unusual ventures that included setting up a photography company, Earhart set out in a new direction.[47]

Boston

Following her parents' divorce in 1924, she drove her mother in the "Yellow Peril" on a transcontinental trip from California with stops throughout the West and even a jaunt up to Banff, Alberta. The meandering tour eventually brought the pair to Boston, Massachusetts, where Earhart underwent another sinus operation which was more successful. After recuperation, she returned to Columbia University for several months but was forced to abandon her studies and any further plans for enrolling at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, because her mother could no longer afford the tuition fees and associated costs. Soon after, she found employment first as a teacher, then as a social worker in 1925 at Denison House, a Boston settlement house.[48] At this time, she lived in Medford, Massachusetts.

When Earhart lived in Medford, she maintained her interest in aviation, becoming a member of the American Aeronautical Society's Boston chapter and was eventually elected its vice president.[49] She flew out of Dennison Airport (later the Naval Air Station Squantum) in Quincy, Massachusetts, and helped finance its operation by investing a small sum of money.[50] Earhart also flew the first official flight out of Dennison Airport in 1927.[51] Along with acting as a sales representative for Kinner aircraft in the Boston area, Earhart wrote local newspaper columns promoting flying and as her local celebrity grew, she laid out the plans for an organization devoted to female flyers.[52]

Transatlantic flight in 1928

Commemoration Stone for Amelia Earhart's 1928 transatlantic flight, next to the quay side in Burry Port, Wales

Photo of Amelia Earhart prior to her transatlantic crossing of June 17, 1928

After Charles Lindbergh's solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927, Amy Guest (1873–1959) expressed interest in being the first woman to fly (or be flown) across the Atlantic Ocean. After deciding that the trip was too perilous for her to undertake, she offered to sponsor the project, suggesting that they find "another girl with the right image". While at work one afternoon in April 1928, Earhart got a phone call from Capt. Hilton H. Railey, who asked her, "Would you like to fly the Atlantic?"

The project coordinators (including book publisher and publicist George P. Putnam) interviewed Earhart and asked her to accompany pilot Wilmer Stultz and copilot/mechanic Louis Gordon on the flight, nominally as a passenger, but with the added duty of keeping the flight log. The team departed from Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland, in a Fokker F.VIIb/3m on June 17, 1928, landing at Pwll near Burry Port, South Wales, exactly 20 hours and 40 minutes later.[53] There is a commemorative blue plaque at the site.[54] Since most of the flight was on instruments and Earhart had no training for this type of flying, she did not pilot the aircraft. When interviewed after landing, she said, "Stultz did all the flying—had to. I was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes." She added, "... maybe someday I'll try it alone."[55]

Earhart reportedly received a rousing welcome on June 19, 1928, when she landed at Woolston in Southampton, England.[56] She flew the Avro Avian 594 Avian III, SN: R3/AV/101 owned by Lady Mary Heath and later purchased the aircraft and had it shipped back to the United States (where it was assigned "unlicensed aircraft identification mark" 7083).[57]

When the Stultz, Gordon and Earhart flight crew returned to the United States, they were greeted with a ticker-tape parade along the Canyon of Heroes in Manhattan, followed by a reception with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House.

Celebrity image

Earhart walking with President Hoover in the grounds of the White House on January 2, 1932

Trading on her physical resemblance to Lindbergh,[58] whom the press had dubbed "Lucky Lindy", some newspapers and magazines began referring to Earhart as "Lady Lindy".[59][Note 7] The United Press was more grandiloquent; to them, Earhart was the reigning "Queen of the Air".[60] Immediately after her return to the United States, she undertook an exhausting lecture tour in 1928 and 1929. Meanwhile, Putnam had undertaken to heavily promote her in a campaign that included publishing a book she authored, a series of new lecture tours and using pictures of her in mass market endorsements for products including luggage, Lucky Strike cigarettes (this caused image problems for her, with McCall's magazine retracting an offer)[61] and women's clothing and sportswear. The money that she made with "Lucky Strike" had been earmarked for a $1,500 donation to Commander Richard Byrd's imminent South Pole expedition.[61]

The marketing campaign by both Earhart and Putnam was successful in establishing the Earhart mystique in the public psyche.[62] Rather than simply endorsing the products, Earhart actively became involved in the promotions, especially in women's fashions. For a number of years she had sewn her own clothes, but the "active living" lines that were sold in 50 stores such as Macy's in metropolitan areas were an expression of a new Earhart image.[63] Her concept of simple, natural lines matched with wrinkle-proof, washable materials was the embodiment of a sleek, purposeful but feminine "A.E." (the familiar name she went by with family and friends).[60][64] The luggage line that she promoted (marketed as Modernaire Earhart Luggage) also bore her unmistakable stamp.

A wide range of promotional items bearing the Earhart name appeared.

Promoting aviation

Studio portrait of Amelia Earhart, c. 1932. Putnam specifically instructed Earhart to disguise a "gap-toothed" smile by keeping her mouth closed in formal photographs.

Celebrity endorsements helped Earhart finance her flying.[65] Accepting a position as associate editor at Cosmopolitan magazine, she turned this forum into an opportunity to campaign for greater public acceptance of aviation, especially focusing on the role of women entering the field.[66] In 1929, Earhart was among the first aviators to promote commercial air travel through the development of a passenger airline service; along with Charles Lindbergh, she represented Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT, later TWA) and invested time and money in setting up the first regional shuttle service between New York and Washington, D.C., the Ludington Airline. She was a Vice President of National Airways, which conducted the flying operations of the Boston-Maine Airways and several other airlines in the northeast.[67] By 1940, it had become Northeast Airlines.

Competitive flying

Although Earhart had gained fame for her transatlantic flight, she endeavored to set an "untarnished" record of her own.[68] Shortly after her return, piloting Avian 7083, she set off on her first long solo flight that occurred just as her name was coming into the national spotlight. By making the trip in August 1928, Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the North American continent and back.[69] Her piloting skills and professionalism gradually grew, as acknowledged by experienced professional pilots who flew with her. General Leigh Wade flew with Earhart in 1929: "She was a born flier, with a delicate touch on the stick."[70]

Earhart subsequently made her first attempt at competitive air racing in 1929 during the first Santa Monica-to-Cleveland Women's Air Derby (nicknamed the "Powder Puff Derby" by Will Rogers), which left Santa Monica on August 18 and arrived at Cleveland on August 26. During the race, she settled into fourth place in the "heavy planes" division. At the second last stop at Columbus, her friend Ruth Nichols, who was coming third, had an accident while on a test flight before the race recommenced. Nichols' aircraft hit a tractor at the start of the runway and flipped over, forcing her out of the race.[71] At Cleveland, Earhart was placed third in the heavy division.[72][73]

In 1930, Earhart became an official of the National Aeronautic Association where she actively promoted the establishment of separate women's records and was instrumental in the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) accepting a similar international standard.[66] In 1931, she set a world altitude record of 18,415 feet (5,613 m), flying a Pitcairn PCA-2[74]autogyro borrowed from Beech-Nut Chewing Gum[75][76][77][78] While to a reader today it might seem that Earhart was engaged in flying "stunts", she was, with other female flyers, crucial to making the American public "air minded" and convincing them that "aviation was no longer just for daredevils and supermen."[79]

During this period, Earhart became involved with The Ninety-Nines, an organization of female pilots providing moral support and advancing the cause of women in aviation. She had called a meeting of female pilots in 1929 following the Women's Air Derby. She suggested the name based on the number of the charter members; she later became the organization's first president in 1930.[6] Earhart was a vigorous advocate for female pilots and when the 1934 Bendix Trophy Race banned women, she openly refused to fly screen actress Mary Pickford to Cleveland to open the races.[80]

Marriage to George Putnam

Earhart and Putnam in 1931

Earhart was engaged to Samuel Chapman, a chemical engineer from Boston; she broke off the engagement on November 23, 1928.[81] During the same period, Earhart and publisher George P. Putnam had spent a great deal of time together. Putnam, who was known as GP, was divorced in 1929 and sought out Earhart, proposing to her six times before she finally agreed to marry him.[Note 8] After substantial hesitation on her part, they married on February 7, 1931, in Putnam's mother's house in Noank, Connecticut. Earhart referred to her marriage as a "partnership" with "dual control". In a letter written to Putnam and hand delivered to him on the day of the wedding, she wrote, "I want you to understand I shall not hold you to any midaevil [sic] code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly."[Note 9][84][85]

Earhart's ideas on marriage were liberal for the time as she believed in equal responsibilities for both breadwinners and pointedly kept her own name rather than being referred to as "Mrs. Putnam". When The New York Times, per the rules of its stylebook, insisted on referring to her as Mrs. Putnam, she laughed it off. Putnam also learned that he would be called "Mr. Earhart".[86] There was no honeymoon for the newlyweds as Earhart was involved in a nine-day cross-country tour promoting autogyros and the tour sponsor, Beech-Nut chewing gum. Although Earhart and Putnam never had children, he had two sons by his previous marriage to Dorothy Binney (1888–1982),[87] a chemical heiress whose father's company, Binney & Smith, invented Crayola crayons:[88] the explorer and writer David Binney Putnam (1913–1992) and George Palmer Putnam, Jr. (1921–2013).[89] Earhart was especially fond of David, who frequently visited his father at their family home, which was on the grounds of The Apawamis Club in Rye, New York. George had contracted polio shortly after his parents' separation and was unable to visit as often.

Transatlantic solo flight in 1932

Amelia Earhart Museum, Derry

Lockheed Vega 5B flown by Amelia Earhart as seen on display at the National Air and Space Museum

Monument in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland and Labrador

On the morning of May 20, 1932, 34-year-old Earhart set off from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, with a copy of the Telegraph-Journal, given to her by journalist Stuart Trueman,[90] intended to confirm the date of the flight.[90] She intended to fly to Paris in her single engine Lockheed Vega 5B to emulate Charles Lindbergh's solo flight five years earlier.[91][Note 10] Her technical advisor for the flight was famed Norwegian American aviator Bernt Balchen who helped prepare her aircraft. He also played the role of "decoy" for the press as he was ostensibly preparing Earhart's Vega for his own Arctic flight.[Note 11] After a flight lasting 14 hours, 56 minutes during which she contended with strong northerly winds, icy conditions and mechanical problems, Earhart landed in a pasture at Culmore, north of Derry, Northern Ireland. The landing was witnessed by Cecil King and T. Sawyer. When a farm hand asked, "Have you flown far?" Earhart replied, "From America".[94][95]

As the first woman to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic, Earhart received the Distinguished Flying Cross from Congress, the Cross of Knight of the Legion of Honor from the French Government and the Gold Medal of the National Geographic Society[96] from President Herbert Hoover. As her fame grew, she developed friendships with many people in high offices, most notably First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Roosevelt shared many of Earhart's interests and passions, especially women's causes. After flying with Earhart, Roosevelt obtained a student permit but did not further pursue her plans to learn to fly. The two friends communicated frequently throughout their lives.[Note 12] Another famous flyer, Jacqueline Cochran, who was considered to be Earhart's greatest rival by both media and the public, also became a confidante and friend during this period.[98]

Additional solo flights

On January 11, 1935, Earhart became the first aviator to fly solo from Honolulu, Hawaii to Oakland, California.[Note 13][99][100][101] Although this transoceanic flight had been attempted by many others, notably by the unfortunate participants in the 1927 Dole Air Race that had reversed the route, her trailblazing[102] flight had been mainly routine, with no mechanical breakdowns. In her final hours, she even relaxed and listened to "the broadcast of the Metropolitan Opera from New York".[102]

In a Stearman-Hammond Y-1

That year, once more flying her Lockheed Vega airliner that Earhart had tagged "old Bessie, the fire horse",[Note 14][104] she flew solo from Los Angeles to Mexico City on April 19. The next record attempt was a nonstop flight from Mexico City to New York. Setting off on May 8, her flight was uneventful although the large crowds that greeted her at Newark, New Jersey were a concern,[105] because she had to be careful not to taxi into the throng.

Earhart again participated in long-distance air racing, placing fifth in the 1935 Bendix Trophy Race, the best result she could manage, due to the stock Lockheed Vega, topping out at 195 mph (314 km/h), was outclassed by purpose-built air racers that reached more than 300 mph (480 km/h).[106] The race had been a particularly difficult one as a competitor, Cecil Allen, died in a fiery takeoff mishap and rival Jacqueline Cochran was forced to pull out due to mechanical problems, the "blinding fog",[107] and violent thunderstorms that plagued the race.

Between 1930 and 1935, Earhart had set seven women's speed and distance aviation records in a variety of aircraft including the Kinner Airster, Lockheed Vega, and Pitcairn Autogiro. By 1935, recognizing the limitations of her "lovely red Vega" in long, transoceanic flights, Earhart contemplated, in her own words, a new "prize ... one flight which I most wanted to attempt – a circumnavigation of the globe as near its waistline as could be".[108] For the new venture, she would need a new aircraft.

Move from New York to California

While Earhart was away on a speaking tour in late November 1934, a fire broke out at the Putnam residence in Rye, destroying many family treasures and Earhart's personal mementos.[109] Putnam had already sold his interest in the New York based publishing company to his cousin, Palmer Putnam. Following the fire, the couple decided to move to the West Coast, where Putnam took up his new position as head of the editorial board of Paramount Pictures in North Hollywood.[110][Note 15] While speaking in California in late 1934, Earhart had contacted Hollywood "stunt" pilot Paul Mantz in order to improve her flying, focusing especially on long-distance flying in her Vega and wanted to move closer to him.

At Earhart's urging, Putnam purchased a small house in June 1935 adjacent to the clubhouse of the Lakeside Golf Club in Toluca Lake, a San Fernando Valley celebrity enclave community nestled between the Warner Brothers and Universal Pictures studio complexes where they had earlier rented a temporary residence.[111][112] Earhart and Putnam would not move in immediately, however; they decided to do considerable remodeling and enlarge the existing small structure to meet their needs. This delayed the occupation of their new home for several months.[113]

In September 1935, Earhart and Mantz formally established a business partnership that they had been considering since late 1934 by creating the short-lived Earhart-Mantz Flying School, which Mantz controlled and operated through his aviation company, United Air Services. The company was located at the Burbank Airport, about five miles (8 km) from Earhart's Toluca Lake home. Putnam handled publicity for the school that primarily taught instrument flying using Link Trainers.[114]

World flight in 1937

Amelia Earhart's Lockheed Electra 10E. During its modification, the aircraft had most of the cabin windows blanked out and had specially fitted fuselage fuel tanks. The round RDF loop antenna can be seen above the cockpit. This image was taken at Luke Field on March 20, 1937; the plane would crash later that morning.

Planning

In 1935, Earhart joined Purdue University as a visiting faculty member to counsel women on careers and as a technical advisor to its Department of Aeronautics.[107][Note 16] Early in 1936, Earhart started planning a round-the-world flight. Although others had flown around the world, her flight would be the longest at 29,000 miles (47,000 km) because it followed a roughly equatorial route. With financing from Purdue,[Note 17] in July 1936, a Lockheed Electra 10E was built at Lockheed Aircraft Company to her specifications, which included extensive modifications to the fuselage to incorporate many additional fuel tanks.[116] Earhart dubbed the twin engine monoplane her "flying laboratory". The plane was built at Lockheed's Burbank, California plant, and after delivery it was hangared at Mantz's United Air Services, which was just across the airfield from the Lockheed plant.[117]

Although the Electra was publicized as a "flying laboratory", little useful science was planned and the flight was arranged around Earhart's intention to circumnavigate the globe along with gathering raw material and public attention for her next book.[118] Earhart chose Captain Harry Manning as her navigator; he had been the captain of the President Roosevelt, the ship that had brought Earhart back from Europe in 1928.[115] Manning was not only a navigator, but he was also a skilled radio operator who knew Morse code.[119]

Earhart and Noonan by the Lockheed L10 Electra at Darwin, Australia on June 28, 1937

Through contacts in the Los Angeles aviation community, Fred Noonan was subsequently chosen as a second navigator because there were significant additional factors that had to be dealt with while using celestial navigation for aircraft.[120][121] He had vast experience in both marine (he was a licensed ship's captain) and flight navigation. Noonan had recently left Pan Am, where he established most of the company's China Clipper seaplane routes across the Pacific. Noonan had also been responsible for training Pan American's navigators for the route between San Francisco and Manila.[122][Note 18] The original plans were for Noonan to navigate from Hawaii to Howland Island, a particularly difficult portion of the flight; then Manning would continue with Earhart to Australia and she would proceed on her own for the remainder of the project.

First attempt

On March 17, 1937, Earhart and her crew flew the first leg from Oakland, California to Honolulu, Hawaii. In addition to Earhart and Noonan, Harry Manning and Mantz (who was acting as Earhart's technical advisor) were on board. Due to lubrication and galling problems with the propeller hubs' variable pitch mechanisms, the aircraft needed servicing in Hawaii. Ultimately, the Electra ended up at the United States Navy's Luke Field on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor. The flight resumed three days later from Luke Field with Earhart, Noonan and Manning on board. During the takeoff run, there was an uncontrolled ground-loop, the forward landing gear collapsed, both propellers hit the ground, the plane skidded on its belly, and a portion of the runway was damaged.[123] The cause of the ground-loop is controversial. Some witnesses at Luke Field, including the Associated Press journalist, said they saw a tire blow.[124] Earhart thought either the Electra's right tire had blown and/or the right landing gear had collapsed. Some sources, including Mantz, cited pilot error.[124]

With the aircraft severely damaged, the flight was called off and the aircraft was shipped by sea to the Lockheed Burbank facility for repairs.[125]

Second attempt

The planned flight route

While the Electra was being repaired Earhart and Putnam secured additional funds and prepared for a second attempt. This time flying west to east, the second attempt began with an unpublicized flight from Oakland to Miami, Florida, and after arriving there Earhart publicly announced her plans to circumnavigate the globe. The flight's opposite direction was partly the result of changes in global wind and weather patterns along the planned route since the earlier attempt. On this second flight, Fred Noonan was Earhart's only crew member. The pair departed Miami on June 1 and after numerous stops in South America, Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, arrived at Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, 1937. At this stage about 22,000 miles (35,000 km) of the journey had been completed. The remaining 7,000 miles (11,000 km) would be over the Pacific.

| Date | Departure city[126] | Arrival city | Nautical miles | Notes[127] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 20, 1937 | Oakland, California | Burbank, California | 283 | |

| May 21, 1937 | Burbank, California | Tucson, Arizona | 393 | |

| May 22, 1937 | Tucson, Arizona | New Orleans, Louisiana | 1070 | Arrived at Lakefront Airport[128] |

| May 23, 1937 | New Orleans, Louisiana | Miami, Florida | 586 | |

| June 1, 1937 | Miami, Florida | San Juan, Puerto Rico | 908 | |

| June 2, 1937 | San Juan, Puerto Rico | Caripito, Venezuela | 492 | Out of Isla Grande Airport |

| June 3, 1937 | Caripito, Venezuela | Paramaribo, Surinam | 610 | |

| June 4, 1937 | Paramaribo, Surinam | Fortaleza, Brazil | 1142 | |

| June 5, 1937 | Fortaleza, Brazil | Natal, Brazil | 235 | |

| June 7, 1937 | Natal, Brazil | Saint-Louis, Senegal | 1727 | Transatlantic flight |

| June 8, 1937 | Saint-Louis, Senegal | Dakar, Senegal | 100 | |

| June 10, 1937 | Dakar, Senegal | Gao, French Sudan | 1016 | |

| June 11, 1937 | Gao, French Sudan | Fort-Lamy, F.E. Africa | 910 | |

| June 12, 1937 | Fort-Lamy, F.E. Africa | El Fasher, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan | 610 | |

| June 13, 1937 | El Fasher, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan | Khartoum, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan | 437 | |

| June 13, 1937 | Khartoum, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan | Massawa, Italian East Africa | 400 | |

| June 14, 1937 | Massawa, Italian East Africa | Assab, Italian East Africa | 241 | |

| June 15, 1937 | Assab, Italian East Africa | Karachi, British India | 1627 | First ever non-stop flight from the Red Sea to India |

| June 17, 1937 | Karachi, British India | Calcutta, British India | 1178 | |

| June 18, 1937 | Calcutta, British India | Akyab, Burma | 291 | |

| June 19, 1937 | Akyab, Burma | Rangoon, Burma | 268 | |

| June 20, 1937 | Rangoon, Burma | Bangkok, Siam | 315 | |

| June 20, 1937 | Bangkok, Siam | Singapore, Straits Settlements | 780 | |

| June 21, 1937 | Singapore, Straits Settlements | Bandoeng, Dutch East Indies | 541 | |

| June 25, 1937 | Bandoeng, Dutch East Indies | Soerabaia, Dutch East Indies | 310 | Delayed due to monsoon |

| June 25, 1937 | Soerabaia, Dutch East Indies | Bandoeng, Dutch East Indies | 310 | Returned for repairs, Earhart ill with dysentery |

| June 26, 1937 | Bandoeng, Dutch East Indies | Soerabaia, Dutch East Indies | 310 | |

| June 27, 1937 | Soerabaia, Dutch East Indies | Koepang, Dutch East Indies | 668 | |

| June 28, 1937 | Koepang, Dutch East Indies | Darwin, Australia | 445 | Direction finder repaired, parachutes removed and sent home |

| June 29, 1937 | Darwin, Australia | Lae, New Guinea | 1012 | |

| July 2, 1937 | Lae, New Guinea | Howland Island | 2556 | Did not arrive |

| July 3, 1937 | Howland Island | Honolulu, Hawaii | 1900 | Planned leg |

| July 4, 1937 | Honolulu, Hawaii | Oakland, California | 2400 | Planned leg |

Departure from Lae

On July 2, 1937, midnight GMT, Earhart and Noonan took off from Lae Airfield (06°43′59″S 146°59′45″E / 6.73306°S 146.99583°E / -6.73306; 146.99583)[129] in the heavily loaded Electra. Their intended destination was Howland Island (0°48′24″N 176°36′59″W / 0.80667°N 176.61639°W / 0.80667; -176.61639Coordinates: 0°48′24″N 176°36′59″W / 0.80667°N 176.61639°W / 0.80667; -176.61639),[130] a flat sliver of land 6,500 ft (2,000 m) long and 1,600 ft (500 m) wide, 10 ft (3 m) high and 2,556 miles (2,221 nmi; 4,113 km) away.[Note 19]

The aircraft departed Lae with about 1100 gallons of gasoline.[131] In March 1937, Kelly Johnson had recommended engine and altitude settings for the Electra. One of the recommended schedules was:[132][Note 20]

| Altitude | RPM | inches | Cambridge[Note 21] | Fuel consumption [gph] | Hours | fuel used [gal] | octane[Note 22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| climb | 2050 | 28.5 | .078 | na | na | 40? | 100 |

| 8000 | 1900 | 28.0 | .073 | 60 | 3 | 220 | 87 |

| 8000 | 1800 | 26.5 | .072 | 51 | 3 | 373 | 87 |

| 8000 | 1700 | 25.0 | .072 | 43 | 3 | 502 | 87 |

| 10000 | 1600 | 24.0 or full throttle | .072 | 38 | 15.7 (calculated) | 1100 | 87 |

Earhart used part of the above schedule for the Oakland to Honolulu leg of the first world flight attempt. Johnson estimated that 900 gallons of fuel would provide 40% more range than required for that leg. Using 900 gallons was 250 gallons less than the Electra's maximum fuel tank capacity; that meant a weight savings of 1,500 pounds (680 kg), so Earhart included Mantz as a passenger on that leg. The Oakland to Honolulu leg had Earhart, Noonan, Manning, and Mantz on board. The flight from Oakland to Honolulu took 16 hours.[133] The Electra also loaded 900 gallons of fuel for the shorter Honolulu to Howland leg (with only Earhart, Noonan, and Manning on board), but the airplane crashed on take off; the crash ended the first world flight attempt.[134]

Around 3 pm Lae time, Earhart reported her altitude as 10000 feet but that they would reduce altitude due to thick clouds. Around 5 pm, Earhart reported her altitude as 7000 feet and speed as 150 knots.[135]

Their last known position report was near the Nukumanu Islands, about 800 miles (700 nmi; 1,300 km) into the flight.

During the flight, Noonan may have been able to do some celestial navigation to determine his position. The plane would cross the International Dateline during the flight; failing to account for the dateline could account for a 1° or 60 mile position error.[136]

Radio equipment

The Electra had radio equipment for both communication and navigation, but details about that equipment are not clear. The Electra failed to establish two-way radio communications with Itasca and failed to radiolocate Itasca. Many explanations have been proposed for those failures.

The plane had a modified Western Electric model 13C transmitter. The 50-watt transmitter was crystal controlled and capable of transmitting on 500 kHz, 3105 kHz, and 6210 kHz.[133] Crystal control means that the transmitter cannot be tuned to other frequencies; the plane could transmit only on those three frequencies. The transmitter had been modified at the factory to provide the 500 kHz capability.

The plane had a modified Western Electric model 20B receiver. Ordinarily, the receiver covered four frequency bands: 188–420 kHz, 550–1500 kHz, 1500–4000 kHz, and 4000–10000 kHz. The receiver was modified to lower the frequencies in the second band to 485–1200 kHz. That modification allowed the reception of 500 kHz signals; such signals were used for marine distress calls and radionavigation.[133][Note 23] The model 20B receiver has two antenna inputs: a low frequency antenna input and a high frequency antenna input. The receiver's band selector also selects which antenna input is used; the first two bands use the low frequency antenna, and the last two bands select the high frequency antenna.[137]

It is unknown whether the model 20B receiver had a beat frequency oscillator that would enable the detection of continuous wave transmissions such as Morse code and radiolocation beacons.[133] Neither Earhart nor Noonan were capable of using Morse code.[131] They relied on voice communications. Manning, who was on the first world flight attempt but not the second, was skilled at Morse and had acquired an FCC aircraft radiotelegraph license for 15 words per minute in March 1937, just prior to the start of the first flight.[119]

A separate automatic radio direction finder receiver, a prototype Hooven Radio Compass,[138] had been installed in the plane in October 1936, but that receiver was removed before the flight to save weight.[139][140] The Hooven Radio Compass was replaced with a Bendix coupling unit that allowed a conventional loop antenna to be attached to an existing receiver (i.e., the Western Electric 20B). The loop antenna is visible above the cockpit on Earhart's plane.

Alternatively, the loop antenna may have been connected to a Bendix RA-1 auxiliary receiver with direction finding capability up to 1500 kHz.[Note 24][Note 25] It is not clear that such a receiver was installed, and if it were, it may have been removed before the flight.[133]Long & Long (1999, p. 115) describes Joe Gurr training Earhart to use a Bendix receiver and other equipment to tune radio station KFI on 640 kHz and determine its direction.

Whichever receiver was used, there are pictures of Earhart's radio direction finder loop antenna and its 5-band Bendix coupling unit.[141] The details of the loop and its coupler are not clear. Long & Long (1999, pp. 63, 68) claim the coupling unit adapted a standard RDF-1-B loop to the RA-1 receiver, and that the system was limited to frequencies below 1430 kHz. During the first world flight attempt's leg from Honolulu to Howland (when Manning was a navigator), Itasca was supposed to transmit a CW homing beacon at either 375 kHz or 500 kHz.[142] At least twice during the world flight, Earhart failed to determine radio bearings at 7500 kHz. If the RDF equipment was not suitable for that frequency, then attempting such a fix would be operator error and fruitless. However, the earlier 7-band Navy RDF-1-A covered 500 kHz–8000 kHz.[143] The later 3-band DU-1 covered 200 kHz–1600 kHz.[144][145] It is not clear where the RDF-1-B or Earhart's coupler performance sits between those two units.[Note 26] In addition, the RDF-1-A and DU-1 coupler designs have other differences. The intention is to have the ordinary receive antenna connected to the coupler's antenna input; from there, it is passed on to the receiver. In the RDF-1-A design, the coupler must be powered on for that design function to work.[Note 27] In the later DU-1 design, the coupler need not be powered.[Note 28]

There were problems with the RDF equipment during the world flight. During the transatlantic leg of the flight (Brazil to Africa), the RDF equipment did not work.[Note 29] The radio direction finding station at Darwin expected to be in contact with Earhart when she arrived there, but Earhart stated that the RDF was not functioning; the problem was a blown fuse.[Note 30] During a test flight at Lae, Earhart could hear radio signals, but she failed to obtain an RDF bearing.[131] While apparently near Howland Island, Earhart reported receiving a 7500 kHz signal from Itasca, but she was unable to obtain an RDF bearing.[146]

The antennas and their connections on the Electra are not certain.[147] A dorsal Vee antenna was added by Bell Telephone Laboratories. There had been a trailing wire antenna for 500 kHz, but the Luke Field accident collapsed both landing gear and wiped off the ventral antennas.[148] After the accident, the trailing wire antenna was removed, the dorsal antenna was modified, and a ventral antenna was installed. It is not certain, but it is likely that the dorsal antenna was only connected to the transmitter (i.e., no "break in" relay), and the ventral antenna was only connected to the receiver.[149] Once the second world flight started, problems with radio reception were noticed while flying across the US; Pan Am technicians may have modified the ventral antenna while the plane was in Miami.[150] At Lae, problems with transmission quality on 6210 kHz were noticed.[151] Once the flight took off from Lae, Lae did not receive radio messages on 6210 kHz (Earhart's daytime frequency) until four hours later (at 2:18 pm); Lae's last reception was at 5:18 pm and was a strong signal; Lae received nothing after that; presumably the plane switched to 3105 kHz (Earhart's nighttime frequency).[131]Itasca heard Earhart on 3105 kHz, but did not hear her on 6210 kHz.[152] TIGHAR postulates that the ventral receiving antenna was scraped off while the Electra taxied to the runway at Lae; consequently, the Electra lost its ability to receive HF transmissions.[Note 31]

Nearing Howland Island

USCGC Itasca was at Howland Island to support the flight.

The USCGC Itasca was on station at Howland. Its task was to communicate with Earhart's Electra and guide them to the island once they arrived in the vicinity. Noonan and Earhart expected to do voice communications on 3105 kHz during the night and 6210 kHz during the day.

Through a series of misunderstandings or errors (the details of which are still controversial), the final approach to Howland Island using radio navigation was not successful. Fred Noonan had earlier written about problems affecting the accuracy of radio direction finding in navigation.[Note 32] Another cited cause of possible confusion was that the Itasca and Earhart planned their communication schedule using time systems set a half-hour apart, with Earhart using Greenwich Civil Time (GCT) and the Itasca under a Naval time zone designation system.[153]

The Electra expected Itasca to transmit signals that the Electra could use as an RDF beacon to find the Itasca. In theory, the plane could listen for the signal while rotating its loop antenna. A sharp minimum indicates the direction of the RDF beacon. The Electra's RDF equipment had failed due to a blown fuse during an earlier leg flying to Darwin; the fuse was replaced.[154] Near Howland, Earhart could hear the transmission from Itasca on 7500 kHz, but she was unable to determine a minimum, so she could not determine a direction to Itasca. Earhart was also unable to determine a minimum during an RDF test at Lae.[131] One likely theory is that Earhart's RDF equipment did not work at 7500 kHz; most RDF equipment at the time was not designed to work above 2000 kHz. When operated above their design frequency, loop antennas lose their directionality.[155][Note 33]

Itasca had its own RDF equipment, but that equipment did not work above 550 kHz,[131] so Itasca could not determine the direction to the Electra's HF transmissions at 3105 and 6210 kHz. The Electra had been equipped to transmit a 500 kHz signal that Itasca could use for radio direction finding, but some of that equipment had been removed. The equipment originally used a long trailing wire antenna. While the plane was in flight, the wire antenna would be paid out at the tail; efficient transmissions at 500 kHz needed a long antenna. The antenna was bulky and heavy, so the trailing wire antenna was removed to save weight. If nothing else had been done, the plane would have been unable to transmit an RDF signal that Itasca could use. Such a modification was made, but without voice communication from Itasca to the plane, the ship could not tell the plane to use its 500 kHz signal.[Note 34] Even if Itasca could get a bearing to the plane, the Itasca could not tell the plane that bearing, so the plane could not head to the ship.

Some sources have noted Earhart's apparent lack of understanding of her direction-finding system, which had been fitted to the aircraft just prior to the flight. The system was equipped with a new receiver from Bendix that operated on five wavelength "bands", marked 1 to 5. The loop antenna was equipped with a tuneable loading coil that changed the effective length of the antenna to allow it to work efficiently at different wavelengths. The tuner on the antenna was also marked with five settings, 1 to 5, but, critically, these were not the same frequency bands as the corresponding bands on the radio. The two were close enough for settings 1, 2 and 3, but the higher frequency settings, 4 and 5, were entirely different. The upper bands (4 and 5) could not be used for direction finding.[156] Earhart's only training on the system was a brief introduction by Joe Gurr at the Lockheed factory, and the topic had not come up. A card displaying the band settings of the antenna was mounted so it was not visible. Gurr explained that higher frequency bands would offer better accuracy and longer range.[157]

Motion picture evidence from Lae suggests that an antenna mounted underneath the fuselage may have been torn off from the fuel-heavy Electra during taxi or takeoff from Lae's turf runway, though no antenna was reported found at Lae. Don Dwiggins, in his biography of Paul Mantz (who assisted Earhart and Noonan in their flight planning), noted that the aviators had cut off their long-wire antenna, due to the annoyance of having to crank it back into the aircraft after each use.

Radio signals

During Earhart and Noonan's approach to Howland Island, the Itasca received strong and clear voice transmissions from Earhart identifying as KHAQQ but she apparently was unable to hear voice transmissions from the ship. Signals from the ship would also be used for direction finding, implying that the aircraft's direction finder was also not functional.

The first calls, routine reports stating the weather as cloudy and overcast, were received at 2:45 and just before 5 am on July 2. These calls were broken up by static, but at this point the aircraft would still be a long distance from Howland.[158]

At 6:14 am another call was received stating the aircraft was within 200 miles (320 km), and requested that the ship use its direction finder to provide a bearing for the aircraft. Earhart began whistling into the microphone to provide a continual signal for them to home in on.[159] It was at this point that the radio operators on the Itasca realized that their RDF system could not tune in the aircraft's 3105 kHz frequency; radioman Leo Bellarts later commented that he "was sitting there sweating blood because I couldn't do a darn thing about it." A similar call asking for a bearing was received at 6:45 am, when Earhart estimated they were 100 miles (160 km) out.[160]

An Itasca radio log (position 1) at 7:30–7:40 am states:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

EARHART ON NW SEZ RUNNING OUT OF GAS ONLY 1/2 HOUR LEFT CANT HR US AT ALL / WE HR HER AND ARE SENDING ON 3105 ES 500 SAME TIME CONSTANTLY[161]

Another Itasca radio log (position 2) at 7:42 am states:

KHAQQ [Earhart's plane] CLNG ITASCA WE MUST BE ON YOU BUT CANNOT SEE U BUT GAS IS RUNNING LOW BEEN UNABLE TO REACH YOU BY RADIO WE ARE FLYING AT A 1000 FEET[162]

Earhart's 7:58 am transmission said she couldn't hear the Itasca and asked them to send voice signals so she could try to take a radio bearing. This transmission was reported by the Itasca as the loudest possible signal, indicating Earhart and Noonan were in the immediate area. They couldn't send voice at the frequency she asked for, so Morse code signals were sent instead. Earhart acknowledged receiving these but said she was unable to determine their direction.[163]

In her last known transmission at 8:43 am Earhart broadcast "We are on the line 157 337. We will repeat this message. We will repeat this on 6210 kilocycles. Wait." However, a few moments later she was back on the same frequency (3105 kHz) with a transmission that was logged as a "questionable": "We are running on line north and south."[164] Earhart's transmissions seemed to indicate she and Noonan believed they had reached Howland's charted position, which was incorrect by about five nautical miles (10 km). The Itasca used her oil-fired boilers to generate smoke for a period of time but the fliers apparently did not see it. The many scattered clouds in the area around Howland Island have also been cited as a problem: their dark shadows on the ocean surface may have been almost indistinguishable from the island's subdued and very flat profile.

Whether any post-loss radio signals were received from Earhart and Noonan remains unclear. If transmissions were received from the Electra, most if not all were weak and hopelessly garbled. Earhart's voice transmissions to Howland were on 3105 kHz, a frequency restricted in the United States by the FCC to aviation use.[Note 35] This frequency was thought to be not fit for broadcasts over great distances. When Earhart was at cruising altitude and midway between Lae and Howland (over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from each) neither station heard her scheduled transmission at 0815 GCT.[166] Moreover, the 50-watt transmitter used by Earhart was attached to a less-than-optimum-length V-type antenna.[167][168][Note 36]

The last voice transmission received on Howland Island from Earhart indicated she and Noonan were flying along a line of position (running N–S on 157–337 degrees) which Noonan would have calculated and drawn on a chart as passing through Howland.[169][Note 37] After all contact was lost with Howland Island, attempts were made to reach the flyers with both voice and Morse code transmissions. Operators across the Pacific and the United States may have heard signals from the downed Electra but these were unintelligible or weak.[170][Note 38]

Some of these reports of transmissions were later determined to be hoaxes but others were deemed authentic. Bearings taken by Pan American Airways stations suggested signals originating from several locations, including Gardner Island (Nikumaroro), 360 miles (580 km) to the SSE.[171][172] It was noted at the time that if these signals were from Earhart and Noonan, they must have been on land with the aircraft since water would have otherwise shorted out the Electra's electrical system.[173][Note 39][174][Note 40] Sporadic signals were reported for four or five days after the disappearance but none yielded any understandable information.[175][Note 41] The captain of USS Colorado later said: "There was no doubt many stations were calling the Earhart plane on the plane's frequency, some by voice and others by signals. All of these added to the confusion and doubtfulness of the authenticity of the reports."[176]

Search efforts

Beginning approximately one hour after Earhart's last recorded message, the USCGC Itasca undertook an ultimately unsuccessful search north and west of Howland Island based on initial assumptions about transmissions from the aircraft. The United States Navy soon joined the search and over a period of about three days sent available resources to the search area in the vicinity of Howland Island. The initial search by the Itasca involved running up the 157/337 line of position to the NNW from Howland Island. The Itasca then searched the area to the immediate NE of the island, corresponding to the area, yet wider than the area searched to the NW. Based on bearings of several supposed Earhart radio transmissions, some of the search efforts were directed to a specific position on a line of 281 degrees (approximately northwest) from Howland Island without evidence of the flyers.[177] Four days after Earhart's last verified radio transmission, on July 6, 1937, the captain of the battleship Colorado received orders from the Commandant, Fourteenth Naval District to take over all naval and coast guard units to coordinate search efforts.[177]

Later search efforts were directed to the Phoenix Islands south of Howland Island.[178] A week after the disappearance, naval aircraft from the Colorado flew over several islands in the group including Gardner Island (now called Nikumaroro), which had been uninhabited for over 40 years. The subsequent report on Gardner read: "Here signs of recent habitation were clearly visible but repeated circling and zooming failed to elicit any answering wave from possible inhabitants and it was finally taken for granted that none were there... At the western end of the island a tramp steamer (of about 4000 tons)... lay high and almost dry head onto the coral beach with her back broken in two places. The lagoon at Gardner looked sufficiently deep and certainly large enough so that a seaplane or even an airboat could have landed or takenoff [sic] in any direction with little if any difficulty. Given a chance, it is believed that Miss Earhart could have landed her aircraft in this lagoon and swum or waded ashore."[Note 42] They also found that Gardner's shape and size as recorded on charts were wholly inaccurate. Other Navy search efforts were again directed north, west and southwest of Howland Island, based on a possibility the Electra had ditched in the ocean, was afloat, or that the aviators were in an emergency raft.[180]

The official search efforts lasted until July 19, 1937.[181] At $4 million, the air and sea search by the Navy and Coast Guard was the most costly and intensive in U.S. history up to that time but search and rescue techniques during the era were rudimentary and some of the search was based on erroneous assumptions and flawed information. Official reporting of the search effort was influenced by individuals wary about how their roles in looking for an American hero might be reported by the press.[182][Note 43] Despite an unprecedented search by the United States Navy and Coast Guard, no physical evidence of Earhart, Noonan or the Electra 10E was found. The aircraft carrier USS Lexington, the battleship USS Colorado, the Itasca, the Japanese oceanographic survey vessel Koshu and the Japanese seaplane tender Kamoi searched for six–seven days each, covering 150,000 square miles (390,000 km2).[183][184]

Immediately after the end of the official search, Putnam financed a private search by local authorities of nearby Pacific islands and waters, concentrating on the Gilberts. In late July 1937, Putnam chartered two small boats and while he remained in the United States, directed a search of the Phoenix Islands, Christmas (Kiritimati) Island, Fanning (Tabuaeran) Island, the Gilbert Islands and the Marshall Islands, but no trace of the Electra or its occupants was found.[185]

Back in the United States, Putnam acted to become the trustee of Earhart's estate so that he could pay for the searches and related bills. In probate court in Los Angeles, Putnam requested to have the "declared death in absentia" seven-year waiting period waived so that he could manage Earhart's finances. As a result, Earhart was declared legally dead on January 5, 1939.[186]

Speculation on disappearance

There has been considerable speculation on what happened to Earhart and Noonan. Most historians hold to the simple "crash and sink" theory, but a number of other possibilities have been proposed, including several conspiracy theories.

Some have suggested that Earhart and Noonan survived and landed elsewhere, but were either never found or killed, making en-route locations like Tarawa unlikely. Proposals have included the uninhabited Gardner Island (400 miles (640 km) from the vicinity of Howland), the Japanese-controlled Marshall Islands (870 miles (1,400 km) at the closest point of Mili Atoll), and the Japanese-controlled Northern Mariana Islands (2,700 miles (4,300 km) from Howland).

Crash and sink theory

Many researchers believe that Earhart and Noonan ran out of fuel while searching for Howland Island, ditched at sea, and perished. The plane would have carried enough fuel to reach Howland with some extra to spare. The extra fuel would cover some contingencies such as headwinds and searching for Howland. The plane could fly a compass course toward Howland through the night. In the morning, the time of apparent sunrise would allow the plane to determine its line of position (a sun line that ran 157°–337°). From that line, the plane could determine how much further it must travel before reaching a parallel sun line that ran through Howland.[187] At 6:14 AM Itasca time, Earhart estimated they were 200 miles away from Howland.[188] As the plane closed with Howland, it expected to be in radio contact with Itasca. With the radio contact, the plane should be able to use radio direction finding (RDF) to head directly for the Itasca and Howland. Unfortunately, the plane was not receiving a radio signal from Itasca, so it would be unable to determine an RDF bearing to the ship.[Note 44] Although Itasca was receiving HF radio signals from the plane, it did not have HF RDF equipment, so it could not determine a bearing to the plane.[Note 45] The communications going to the plane were almost non-existent.[Note 46] Consequently, the plane was not directed to Howland; it was left on its own with little fuel. Presumably, the plane reached the parallel sun line and started searching for Howland on that line of position. At 7:42 AM, Earhart reported, "We must be on you, but cannot see you – but gas is running low. Have been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet."[187][Note 47] At 8:43 AM, Earhart reported, "We are on the line 157 337. We will repeat this message. We will repeat this on 6210 kilocycles. Wait."[187]

Navigator and aeronautical engineer Elgen Long and his wife Marie K. Long devoted 35 years of research to the "crash and sink" theory.[189] United States Navy Captain Laurance Safford (retired) who was responsible for the interwar Mid-Pacific Strategic Direction Finding Net, and the decoding of the Japanese Purple cipher messages for the attack on Pearl Harbor, began a lengthy analysis of the Earhart flight during the 1970s. His research included the intricate radio transmission documentation. Safford came to the conclusion, "poor planning, worse execution".[190] Rear Admiral Richard R. Black, USN, who was in administrative charge of the Howland Island airstrip and was present in the radio room on the Itasca, asserted in 1982 that "the Electra went into the sea about 10 am, July 2, 1937 not far from Howland".[191] British aviation historian Roy Nesbit interpreted evidence in contemporary accounts and Putnam's correspondence and concluded Earhart's Electra was not fully fueled at Lae.[192] William L. Polhemous, the navigator on Ann Pellegreno's 1967 flight that followed Earhart and Noonan's original flight path, studied navigational tables for July 2, 1937, and thought Noonan may have miscalculated the "single line approach" intended to "hit" Howland.[193]

David Jourdan, a former Navy submariner and ocean engineer specializing in deep-sea recoveries, has claimed any transmissions attributed to Gardner Island were false. Through his company Nauticos he extensively searched a 1,200-square-mile (3,100 km2) quadrant north and west of Howland Island during two deep-sea sonar expeditions (2002 and 2006, total cost $4.5 million) and found nothing. The search locations were derived from the line of position (157–337) broadcast by Earhart on July 2, 1937.[153] Nevertheless, Elgen Long's interpretations have led Jourdan to conclude, "The analysis of all the data we have – the fuel analysis, the radio calls, other things – tells me she went into the water off Howland."[153] Earhart's stepson George Palmer Putnam Jr. has been quoted as saying he believes "the plane just ran out of gas".[194] Susan Butler, author of the Earhart biography East to the Dawn, says she thinks the aircraft went into the ocean out of sight of Howland Island and rests on the seafloor at a depth of 17,000 feet (5 km).[195] Tom D. Crouch, Senior Curator of the National Air and Space Museum, has said the Earhart/Noonan Electra is "18,000 ft. down" and may even yield a range of artifacts that could rival the finds of the Titanic, adding that "the mystery is part of what keeps us interested. In part, we remember her because she's our favorite missing person."[153]

Gardner Island hypothesis

Gardner (Nikumaroro) Island in 2014. "Seven Site" is a focus of the search for Amelia Earhart's remains.

The Gardner Island (Nikumaroro) hypothesis assumes that Earhart and Noonan, having not found Howland Island, would not waste time searching for Howland. Instead, they would turn to the south and look for other islands. The 157/337 radio transmission suggests they flew a course of 157° that would take them past Baker Island; if they missed Baker Island, then sometime later they would fly over the Phoenix Islands, now part of the Republic of Kiribati, about 350 nautical miles (650 km) south-southeast of Howland Island. The Gardner Island hypothesis has the plane making it to Gardner Island (now Nikumaroro), one of the Phoenix Islands.

A week after Earhart disappeared, Navy planes from USS Colorado (which had sailed from Pearl Harbor) searched Gardner Island. The planes saw signs of recent habitation and the wreck of the SS Norwich City, but did not see any signs of Earhart's plane or people. After the Navy ended its search, G. P. Putnam undertook a search in the Phoenix Group and other islands,[196] but nothing was found.

In October 1937, Eric Bevington and Henry E. Maude visited Gardner with some potential settlers. A group walked all the way around the island, but did not find a plane or other evidence.[197]

In December 1938, laborers landed on the island and started constructing the settlement.[198]

In late 1939, USS Bushnell did a survey of the island.[199]

Around April 1940, a skull was discovered and buried, but British colonial officer Gerald Gallagher, did not learn of it until September.[200] Gallagher did a more thorough search of discovery area, including looking for artifacts such as rings. The search found more bones, a bottle, a shoe, and a sextant box. On September 23, 1940, Gallagher radioed his superiors that he had found a "skeleton ... possibly that of a woman", along with an old-fashioned sextant box, under a tree on the island's southeast corner. Gallagher stated the "Bones look more than four years old to me but there seems to be very slight chance that this may be remains of Amelia Earhardt." He was ordered to send the remains to Fiji. On 4 April 1941, Dr. D. W. Hoodless of the Central Medical School examined the bones, took measurements, and wrote a report. Using Karl Pearson's formulas for stature and the lengths of the femur, tibia, and humerus, Hoodless concluded that the person was about 5 feet 5.5 inches (166.4 cm) tall. Hoodless also wrote "it may be definitely stated that the skeleton is that of a MALE." [Emphasis in original.] Hoodless further stated, "Owing to the weather-beaten condition of all the bones it is impossible to be dogmatic in regard to the age of the person at the time of death, but I am of the opinion that he was not less than 45 years of age and that probably he was older: say between 45 and 55 years." Hoodless offered to make more detailed measurements if needed, but suggested any further examination be done by the Anthropological Department at Sydney University.[201][202] These bones were misplaced in Fiji long ago and cannot be reexamined.[203]

In 1998, an analysis of the measurement data by forensic anthropologists found instead that the skeleton had belonged to a "tall white female of northern European ancestry".[204] However, a 2015 review of both analyses concluded that "the most robust scientific analysis and conclusions are those of the original British finding indicating that the Nikumaroro bones belonged to a robust, middle-aged man, not Amelia Earhart."[205]

A 2018 study by American anthropologist Richard Jantz (one of the authors of the 1998 TIGHAR report) estimated the size of Earhart's skeleton based on photographs and reanalyzed the earlier data using modern forensic techniques. Based on measurements of 2,700 Americans who died in the mid-20th century, the study concluded that Earhart's bone measurements more closely matched the Nikumaroro bones than 99% of the reference sample.[206] However, others criticized the study for being based on little factual evidence (in particular seven measurements from the skeleton done in 1941, combined with estimates about Earhart's size based on photos) and doubted the accuracy of those measurements.[207]

During World War II, US Coast Guard LORAN Unit 92, a radio navigation station built in the summer and fall of 1944, and operational from mid-November 1944 until mid-May 1945, was located on Gardner Island's southeast end. Dozens of U.S. Coast Guard personnel were involved in its construction and operation, but were mostly forbidden from leaving the small base or having contact with the Gilbertese colonists then on the island, and found no artifacts known to relate to Earhart.[208]

In 1988, The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) began an investigation[209] of the Earhart/Noonan disappearance and since then has sent ten[210] research expeditions to Gardner Island/Nikumaroro. They have suggested Earhart and Noonan may have flown without further radio transmissions[211] for two and a half hours along the line of position Earhart noted in her last transmission received at Howland, then found the then-uninhabited Gardner Island, landed the Electra on an extensive reef flat near the wreck of a large freighter (the SS Norwich City) on the northwest side of the atoll, and ultimately perished. In 2012, a photograph taken in October 1937 of the reef at Nikumaroro after her disappearance was enhanced. According to the analysts who viewed it, "a blurry object sticking out of the water in the lower left corner of the black-and-white photo is consistent with a strut and wheel of a Lockheed Electra landing gear".[212]

TIGHAR's research has produced a range of archaeological and anecdotal evidence supporting this hypothesis.[213][214] TIGHAR has sent a number of expeditions to Nikumaroro looking for evidence, although they have found nothing conclusive; expeditions include ones in 2007, 2010, 2012, and 2017.[215][216][217][218][219][220] Artifacts discovered by TIGHAR on Nikumaroro have included improvised tools; an aluminum panel, possibly from an Electra, made using 1930s manufacturing specifications; an oddly cut piece of clear Plexiglas the same thickness and curvature of an Electra window; and a size 9 Cat's Paw heel dating from the 1930s, which resembles Earhart's footwear in world flight photos.[221][Note 48] Recently rediscovered photos of Earhart's Electra just before departure in Miami show an aluminum panel over a window on the right side. Ric Gillespie, head of TIGHAR, claimed the found aluminum panel artifact has the same dimensions and rivet pattern as the one shown in the photo "to a high degree of certainty".[222][223] Based on this new evidence, Gillespie returned to the atoll in June 2015, but operations using a remotely operated underwater vehicle to investigate a sonar detection of a possible wreckage were hampered by technical problems. Further, a review of sonar data concluded it was most likely a coral ridge.[224] The evidence remains circumstantial, but Earhart's surviving stepson, George Putnam Jr., has expressed support for TIGHAR's research.[225]

In July 2017, staff from the New England Air Museum notified TIGHAR that the unique rivet pattern of the aluminum panel precisely matched the top of the wing of a C-47B in the museum inventory;[citation needed] particularly significant since a C-47B crashed on a nearby island during World War II and villagers acknowledged bringing aluminum from that wreck to Gardner Island.[226] As of November 2018[update], TIGHAR has not published this new information.

The sextant box found near the bones on Nikumaroro and alleged to belong to Fred Noonan had two apparent serial numbers on it: 3500 and 1542. In October 2018, documents discovered at the National Archives and Records Administration showed USS Bushnell had a Brandis and Sons sextant with USNO serial number 1542 in 1938-1939, well after Earhart's disappearance. The USS Bushnell, a U.S. Navy submarine tender that was assigned to hydrographic surveys in December 1937, visited Nikumaroro and surveyed the island and its lagoon using sextants around November 1939, before the sextant box was discovered by Gallagher in September 1940. A Brandis and Sons sextant with serial number 3500 would have been made around the time of World War I.[199][227][228]

A few news articles have considered TIGHAR's theory, and generally consider it the most plausible of the "Earhart survived" theories, although not proven over crash-and-sink.[229][230][231] Other news articles have criticized TIGHAR as seizing on unlikely possibilities as circumstantial evidence; for example, an article criticized the suggestion that a can of freckle ointment found on Nikumaroro might have been Earhart's, when the Electra was "virtually a flying gas station" with little room for amenities, as Earhart and Noonan carried extra gas tanks in every scrap of available space.[232]

Japanese capture theory

Another theory is that Earhart and Noonan were captured by Japanese forces, perhaps after somehow navigating to somewhere within the Japanese South Pacific Mandate.

In 1966, CBS Correspondent Fred Goerner published a book claiming that Earhart and Noonan were captured and executed when their aircraft crashed on the island of Saipan, part of the Northern Mariana Islands archipelago.[233][234][Note 49][235][Note 50] Saipan is more than 2,700 miles away from Howland Island, however. Later proponents of the Japanese capture hypothesis have generally suggested the Marshall Islands instead, which while still distant from the intended location (~800 miles), is slightly more possible.[232]

In 1990, the NBC-TV series Unsolved Mysteries broadcast an interview with a Saipanese woman who claimed to have witnessed Earhart and Noonan's execution by Japanese soldiers. No independent confirmation has ever emerged for any of these claims.[236] Various purported photographs of Earhart during her captivity have been identified as either fraudulent or having been taken before her final flight.[237]

A slightly different version of the Japanese capture hypothesis is not that the Japanese captured Earhart, but rather that they shot down her plane. Henri Keyzer-Andre, a former Pan Am pilot, propounded this view in his 1993 book Age Of Heroes: Incredible Adventures of a Pan Am Pilot and his Greatest Triumph, Unravelling the Mystery of Amelia Earhart.[238]

Since the end of World War II, a location on Tinian, which is five miles (8 km) southwest of Saipan, had been rumored to be the grave of the two aviators. In 2004, an archaeological dig at the site failed to turn up any bones.[239]

A recent proponent of this theory is Mike Campbell, who published the 2012 book Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last in its favor.[240] Campbell cites claims from Marshall Islanders to have witnessed a crash, as well as a U.S. Army Sergeant who found a suspicious gravesite near a former Japanese prison on Saipan.[241][242]