Operation Nordwind

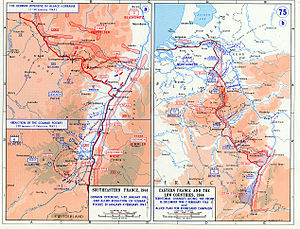

Operation Nordwind (German: Unternehmen Nordwind) was the last major German offensive of World War II on the Western Front. It began on 31 December 1944 in Rhineland-Palatinate, Alsace and Lorraine in southwestern Germany and northeastern France, and ended on 25 January 1945.

Contents

1 Objectives

2 Offensive

3 See also

4 References

5 Notes

6 Bibliography

7 External links

Objectives

In a briefing at his military command complex at Adlerhorst, Adolf Hitler declared in his speech to his division commanders on 28 December 1944 (three days prior to the launch of Operation Nordwind): "This attack has a very clear objective, namely the destruction of the enemy forces. There is not a matter of prestige involved here. It is a matter of destroying and exterminating the enemy forces wherever we find them."[3]:499

The goal of the offensive was to break through the lines of the U.S. Seventh Army and French 1st Army in the Upper Vosges mountains and the Alsatian Plain, and destroy them, as well as the seizure of Strasbourg, which Himmler had promised would be captured by 30 January. This would leave the way open for Operation Dentist (Unternehmen Zahnarzt), a planned major thrust into the rear of the U.S. Third Army which would lead to the destruction of that army.[3]:494

Offensive

On 31 December 1944, German Army Group G—commanded by Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz—and Army Group Oberrhein ("Upper Rhein")—commanded by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler—launched a major offensive against the thinly stretched, 110 kilometres (68 mi)-long front line held by the U.S. 7th Army. Operation Nordwind soon had the understrength U.S. 7th Army in dire straits. The 7th Army—at the orders of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower—had sent troops, equipment, and supplies north to reinforce the American armies in the Ardennes involved in the Battle of the Bulge.

On the same day that the German Army launched Operation Nordwind, the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) committed almost 1,000 aircraft in support. This attempt to cripple the Allied air forces based in northwestern Europe was known as Operation Bodenplatte, which failed without having achieved any of its key objectives.

The initial Nordwind attack was conducted by three Corps of the German 1st Army of Army Group G, and by 9 January, the XXXIX Panzer Corps was heavily engaged as well. By 15 January at least seventeen German divisions (including units in the Colmar Pocket) from Army Group G and Army Group Oberrhein, including the 6th SS Mountain, 17th SS Panzergrenadier, 21st Panzer, and 25th Panzergrenadier Divisions were engaged in the fighting. Another smaller attack was made against the French positions south of Strasbourg, but it was finally stopped. The U.S. VI Corps—which bore the brunt of the German attacks—was fighting on three sides by 15 January.

The 125th Regiment of the 21st Panzer Division under Col. Hans von Luck aimed to sever the American supply line to Strasbourg, by cutting across the eastern foothills of the Vosges at the northwest base of a natural salient in a bend of the River Rhine. Here the Maginot Line ran east-west, and now "showed what a superb fortification it was". On January 7 Luck approached the Line south of Wissembourg at the villages of Rittershoffen and Hatten. Heavy American fire came from the 79th Infantry Division, the 14th Armoured Division, plus elements of the 42nd Infantry Division. On January 10 Luck reached the villages. Two weeks of heavy fighting followed. Germans and Americans each occupying parts of the villages while civilians sheltered in cellars. Luck later said that the fighting around Rittershoffen had been "one of the hardest and most costly battles that ever raged".[6]

Eisenhower, fearing the outright destruction of the U.S. 7th Army, had rushed already battered divisions hurriedly relieved from the Ardennes, southeast over 100 km (62 mi), to reinforce the 7th Army. But their arrival was delayed, and on 21 January with supplies and ammunition short, Seventh Army ordered the much-depleted 79th and 14th Divisions to retreat from Rittershoffen and fall back on new positions on the south bank of the Moder River.

On 25 January the German offensive was halted, after the US 222nd Infantry Regiment stopped their advance near Haguenau, and earning the Presidential Unit Citation in the process. This was the same day that the reinforcements began to arrive from the Ardennes. Strasbourg was saved but the Colmar Pocket was a danger which had to be eliminated.

The German offensive was a failure, failing to destroy the enemy's forces.

See also

- Battle of the Bulge

- Operation Spring Awakening

References

^ Cirillo 2003, Retrieved 16 August 2018

^ Cirillo 2003, Retrieved 16 August 2018

^ abc Clarke, Jeffrey J.; Smith, Robert Ross (1993). Riviera to the Rhine (CMH Pub 7–10) (PDF). Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. Retrieved 1 May 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Zabecki, David T. (2014). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History. ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

^ Cirillo 2003, Retrieved 16 August 2018

^ Ambrose 1997, p. 386.

Notes

^ As elsewhere, casualty figures are only rough estimates, and the figures presented are based on the postwar "Seventh Army Operational Report, Alsace Campaign and Battle Participation, 1 June 1945" (copy CMH), which notes 11,609 Seventh Army battle casualties for the period, plus 2,836 cases of trench foot and 380 cases of frostbite, and estimates about 17,000 Germans killed or wounded with 5,985 processed prisoners of war. But the VI Corps AAR for January 1945 puts its total losses at 14,716 (773 killed, 4,838 wounded, 3,657 missing, and 5,448 nonbattle casualties); and Albert E. Cowdrey and Graham A. Cosmas, "The Medical Department: The War Against Germany," draft CMH MS (1988), pp. 54-55, a forthcoming volume in the United States Army in World War II series, reports Seventh Army hospitals processing about 9,000 wounded and 17,000 "sick and injured" during the period. Many of these, however, may have been returned to their units, and others may have come from American units operating in the Colmar area but still supported by Seventh Army medical services. Von Luttichau's "German Operations," ch. 29, pp. 39-40, puts German losses at 22,932.

Bibliography

- Bonn, Keith E. When the Odds Were Even: The Vosges Mountains Campaign, October 1944 – January 1945. Novato, CA: Presidio, 2006.

- Engler, Richard. The Final Crisis: Combat in Northern Alsace, January 1945. Aberjona Press. 1999.

ISBN 9780966638912

Nordwind & the US 44th Division *Battle History of the 44th I.D.

Whiting, Charles (1992). The Other Battle of the Bulge: Operation Northwind. Avon Books. ISBN 0380716283. OCLC 211992045.

Citino, Robert (2017), The Wehrmacht’s Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944–1945, University Press of Kansas, ISBN 9780700624942

External links

Cirillo, Roger. The Ardennes-Alsace. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72–26.

The NORDWIND Offensive (January 1945) on the website of the 100th Infantry Division Association contains a list of German primary sources on the operation.