Blue plaque

English Heritage blue plaque commemorating Ian Fleming at 22b Ebury Street, Belgravia, London (erected 1996)

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term is used in the United Kingdom in two different senses. It may be used narrowly and specifically to refer to the "official" scheme administered by English Heritage, and currently restricted to sites within Greater London; or it may be used less formally to encompass a number of similar schemes administered by organisations throughout the UK.

The "official" scheme traces its origins to that launched in 1866 in London, on the initiative of the politician William Ewart, to mark the homes and workplaces of famous people.[1][2] It has been administered successively by the Society of Arts (1866–1901), the London County Council (1901–1965), the Greater London Council (1965–1986) and English Heritage (1986 to date). It remains focused on London (now defined as Greater London), although between 1998 and 2005, under a trial programme since discontinued, 34 plaques were erected elsewhere in England. The first such scheme in the world, it has directly or indirectly provided the inspiration and model for many others.

Many other plaque schemes have since been initiated in the United Kingdom. Some are restricted to a specific geographical area, others to a particular theme of historical commemoration. They are administered by a range of bodies including local authorities, civic societies, residents' associations and other organisations such as the Transport Trust, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America and the British Comic Society. The plaques erected are made in a variety of designs, shapes, materials and colours: some are blue, others are not. However, the term "blue plaque" is often used informally to encompass all such schemes.

There are also commemorative plaque schemes throughout the world such as those in Paris, Rome, Oslo, Dublin; and in other cities in Australia, Canada, the Philippines, Russia and the United States. The forms these take vary, and they are more likely to be known as historical markers.

Contents

1 In the United Kingdom

1.1 English Heritage scheme

1.1.1 History

1.1.2 Criteria

1.1.3 Selection process

1.1.4 Event plaques

1.1.5 Outside London

1.2 Other schemes

1.2.1 London

1.2.2 Northern Ireland

1.2.3 Elsewhere

1.2.4 Thematic schemes

1.3 Examples

2 In other countries

3 References

4 Further reading

5 External links

In the United Kingdom

Society of Arts plaque on Samuel Johnson's house in Gough Square, London (erected 1876). Many of the early Society of Arts and LCC plaques were brown in colour.

London County Council plaque at 48 Doughty Street, Holborn, commemorating Charles Dickens (erected 1903)

London County Council plaque at 100 Lambeth Road, Lambeth, commemorating William Bligh (erected 1952)

Greater London Council plaque at 29 Fitzroy Square, Fitzrovia, commemorating Virginia Woolf (erected 1974)

English Heritage plaque at 153 Cromwell Road, London, SW5, commemorating Sir Alfred Hitchcock (erected 1999)

Plaque at 22 Gladstone Avenue, Feltham, London, commemorating Freddie Mercury (erected 2016)

English Heritage scheme

The original blue plaque scheme was established by the Society of Arts in 1867, and since 1986 has been run by English Heritage. It is the oldest such scheme in the world.[2][1] Since 1984 English Heritage have commissioned Frank Ashworth to make the plaques which have then been inscribed by his wife, Sue, at their home in Cornwall.[3]

English Heritage plans to erect an average of twelve new blue plaques each year in London.[4] Many are unveiled by prominent public people: for example, in 2010 a plaque dedicated to John Lennon was unveiled in Montagu Square by Yoko Ono, at the house where the couple shot the cover of the album Two Virgins.[5]

History

After being conceived by politician William Ewart in 1863, the scheme was initiated in 1866 by Ewart, Henry Cole and the Society of Arts (now the Royal Society of Arts),[6] which erected plaques in a variety of shapes and colours.

The first plaque was unveiled in 1867 to commemorate Lord Byron at his birthplace, 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square. This house was demolished in 1889. The earliest blue plaque to survive, also put up in 1867, commemorates Napoleon III in King Street, St James's.[2] Byron’s plaque was blue, but the colour was changed by the manufacturer Minton, Hollins & Co to chocolate brown to save money.[7]

In total the Society of Arts put up 35 plaques, fewer than half of which survive today. The Society only erected one plaque within the square-mile of the City of London, that to Samuel Johnson on his house in Gough Square, in 1876. In 1879, it was agreed that the City of London Corporation would be responsible for erecting plaques within the City to recognise its jurisdictional independence. This demarcation has remained ever since.[2]

In 1901, the Society of Arts scheme was taken over by the London County Council (LCC),[1] which gave much thought to the future design of the plaques. It was eventually decided to keep the basic shape and design of the Society's plaques, but to make them uniformly blue, with a laurel wreath and the LCC's title.[8] Though this design was used consistently from 1903 to 1938, some experimentation occurred in the 1920s, and plaques were made in bronze, stone and lead. Shape and colour also varied.[8]

In 1921, the most common (blue) plaque design was revised, as it was discovered that glazed ceramic Doulton ware was cheaper than the encaustic formerly used. In 1938, a new plaque design was prepared by an unnamed student at the LCC's Central School of Arts and Crafts and was approved by the committee. It omitted the decorative elements of earlier plaque designs, and allowed for lettering to be better spaced and enlarged. A white border was added to the design shortly after, and this has remained the standard ever since.[7] No plaques were erected between 1915 and 1919, or between 1940 and 1947, owing to the two world wars.[9] The LCC formalised the selection criteria for the scheme in 1954.[2]

When the LCC was abolished in 1965, the scheme was taken over by the Greater London Council (GLC). The principles of the scheme changed little, but now applied to the entire, much larger, administrative county of Greater London. The GLC was also keen to broaden the range of people commemorated. The GLC erected 252 plaques, the subjects including Sylvia Pankhurst,[10]Samuel Coleridge-Taylor,[11] and Mary Seacole.[12]

In 1986, the GLC was disbanded and the blue plaques scheme passed to English Heritage. English Heritage erected more than 300 plaques in London.

In January 2013 English Heritage suspended proposals for plaques owing to funding cuts.[9][13] The National Trust's chairman stated that his organisation might step in to save the scheme.[14] In the event the scheme was relaunched by English Heritage in June 2014 with private funding (including support from a new donors' club, the Blue Plaques Club, and from property developer David Pearl).[15] Two members of the advisory panel, Professor David Edgerton and author and critic Gillian Darley, resigned over this transmutation, concerned that the scheme had been "reduced to a marketing tool for English Heritage".[16]

In April 2015, English Heritage was divided into two parts, Historic England (a statutory body), and the new English Heritage Trust (a charity, which took over the English Heritage operating name and logo). Responsibility for the blue plaque scheme passed to the English Heritage Trust.

Criteria

To be eligible for an English Heritage blue plaque in London the famous person concerned must:[17]

- Have been dead for 20 years or have passed the centenary of their birth. Fictional characters are not eligible;

- Be considered eminent by a majority of members of their own profession; have made an outstanding contribution to human welfare or happiness;

- Have lived or worked in that building in London (excluding the City of London and Whitehall) for a significant period, in time or importance, within their life and work; be recognisable to the well-informed passer-by, or deserve national recognition.

In cases of foreigners and overseas visitors, candidates should be of international reputation or significant standing in their own country.

With regards to the location of a plaque:

- Plaques can only be erected on the actual building inhabited by a figure, not the site where the building once stood, or on buildings that have been radically altered;

- Plaques are not placed onto boundary walls, gate piers, educational or ecclesiastic buildings, or the Inns of Court;

- Buildings marked with plaques should be visible from the public highway;

- A single person may not be commemorated with more than one blue plaque in London.[17]

Other schemes have different criteria, which are often less restrictive: in particular, it is common under other schemes for plaques to be erected to mark the sites of demolished buildings.

Selection process

Almost all the proposals for English Heritage blue plaques are made by members of the public who write or email the organisation before submitting a formal proposal.[18]

English Heritage's in-house historian researches the proposal, and the Blue Plaques Panel advises on which suggestions should be successful. This is composed of 9 people from various disciplines from across the country. The panel is chaired by Professor Ronald Hutton, and includes former Poet Laureate Professor Sir Andrew Motion and buildings historian Professor Gavin Stamp.[19] The actor and broadcaster Stephen Fry was formerly a member of the panel, and wrote the foreword to the book Lived in London: Blue Plaques and the Stories Behind Them (2009).[20]

Roughly a third of proposals are approved in principle, and are placed on a shortlist. Because the scheme is so popular, and because a lot of detailed research has to be carried out, it takes about three years for each case to reach the top of the shortlist. Proposals not taken forward can only be re-proposed once 10 years have elapsed.[17]

Greater London Council event plaque[21] at Alexandra Palace, commemorating the launch of BBC Television in 1936 (erected 1977)

Event plaques

A small minority of GLC and English Heritage plaques have been erected to commemorate events which took place at particular locations rather than the famous people who lived there.

Outside London

English Heritage plaque[22] at 40 Falkner Square, Liverpool, commemorating Peter Ellis, architect (erected 2001)

In 1998, English Heritage initiated a trial national plaques scheme, and over the following years erected 34 plaques in Birmingham, Merseyside, Southampton and Portsmouth. The scheme was discontinued in 2005. Although English Heritage no longer erects plaques outside Greater London, it does provide advice and guidance to individuals and organisations interested or involved in doing so.[23]

Other schemes

The popularity of English Heritage's London blue plaques scheme has meant that a number of comparable schemes have been established elsewhere in the United Kingdom. Many of these schemes also use blue plaques, often manufactured in metal or plastic rather than the ceramic used in London, but some feature plaques of different colours and shapes. In July 2012, English Heritage published a register of plaque schemes run by other organisations across England.[24]

The criteria for selection varies greatly. Many schemes treat plaques primarily as memorials and place them on the sites of former buildings, in contrast to the strict English Heritage policy of only installing a plaque on the actual building in which a famous person lived or an event took place.

London

Corporation of London plaque on the site of Lloyd's Coffee House in Lombard Street

City of Westminster green plaque at 18 Cavendish Square, Marylebone, commemorating Josef Dallos, contact lens pioneer (erected 2010)

The Corporation of London continues to run its own plaque scheme for the City of London, where English Heritage does not erect plaques. City of London plaques are blue and ceramic, but are rectangular in shape and carry the City of London coat of arms.[2][25] Because of the rapidity of change in the built environment within the City, a high proportion of Corporation of London plaques mark the sites of former buildings.

Many of the 32 London boroughs also now have their own schemes, running alongside the English Heritage scheme. Westminster City Council runs a green plaque scheme, each plaque being sponsored by a group with a particular interest in its subject.[26] The London Borough of Southwark started its own blue plaque scheme in 2003, under which the borough awards plaques through popular vote following public nomination: living people may be commemorated.[27] The London Borough of Islington has a very similar green heritage plaque scheme, initiated in 2010.[28]

Other plaques may be erected by smaller groups, such as residents' associations. In 2007 The Hampstead Garden Suburb Residents Association erected a blue plaque in memory of Prime Minister Harold Wilson at 12 Southway as part of the centenary celebrations of Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland the Ulster History Circle is one of a small number of groups administering blue plaques. Established in 1983, it has erected around 140 plaques.[29]Belfast City Council also has a scheme.[30]

Elsewhere

Oxfordshire blue plaque board commemorating the first sub-4-minute mile run by Roger Bannister on 6 May 1954 at Oxford University's Iffley Road track

The Birmingham Civic Society provides a blue plaque scheme in and around Birmingham: there are over 90 plaques commemorating notable former Birmingham residents and historical places of interest.[31][32]

A scheme in Manchester is co-ordinated by Manchester Art Gallery, to whom nominations can be submitted. Plaques must be funded by those who propose them.[33][34] From 1960 to 1984 all plaques were ceramic, and blue in colour. From 1985, they were made of cast aluminium, colour-coded to reflect the type of commemoration (blue for people; red for events in the city's social history; black for buildings of architectural or historic interest; green for other subjects). After a period of abeyance, the scheme has been revived and all plaques are now patinated bronze.[33]

Plaque in Oldham marking the origin of the fish and chip shop and the fast food industry

A blue plaque at Oldham's Tommyfield Market (Greater Manchester) marks the 1860s origin of the fish and chip shop and fast food industries.[35]

Bournemouth Borough Council has unveiled more than 30 blue plaques.[36] Its first plaque was unveiled on 31 October 1937 to Lewis Tregonwell, who built the first house in what is now Bournemouth. Two further plaques followed in 1957 and 1975 to writer Robert Louis Stevenson and poet Rupert Brooke respectively. The first blue plaque was unveiled on 30 June 1985 dedicated to Percy Florence Shelley.[37]

The Hertfordshire town of Berkhamsted unveiled a set of 32 blue plaques in 2000 on some of the town's most significant buildings,[38] including Berkhamsted Castle, the birthplace of writer Graham Greene and buildings associated with the poet William Cowper, John Incent (a Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral) and Clementine Churchill. The plaques feature in a Heritage Trail promoted by the town's council.[39]

Wolverhampton Civic Society plaque at Wolverhampton Science Park marking the location of the world altitude balloon record, on 5 September 1862

Wolverhampton has over 90 blue plaques erected by the Wolverhampton Civic and Historical Society in a scheme which started in 1983.[40] One of the more unusual plaques marks the location of the World Altitude Balloon Record on Friday 5 September 1862.

The Essex town of Loughton inaugurated a scheme in 1997 following a programme allowing for three new plaques a year; 39 had been erected by 2015. The aim is to stimulate public interest in the town's heritage.[41] Among the Loughton blue plaques is that to Mary Anne Clarke, which is in fact a pair of identical plaques, one on the back, and one on the front, of her house, Loughton Lodge.

In 2005, Malvern Civic Society and Malvern Hills District council announced that blue plaques would be placed on buildings in Malvern that were associated with famous people, including Franklin D. Roosevelt. Since then blue plaques have been erected to commemorate C. S. Lewis, Florence Nightingale, Charles Darwin and Haile Selassie.[42][43][44]

In 2010, Derbyshire County Council allowed its residents to vote via the Internet on a shortlist of notable historical figures to be commemorated in a local blue plaque scheme.[45] The first six plaques commemorated industrialist Richard Arkwright junior (Bakewell), Olave Baden-Powell and the "Father of Railways" George Stephenson (Chesterfield), the mathematical prodigy Jedediah Buxton (Elmton), actor Arthur Lowe (Hayfield), and architect Joseph Paxton (Chatsworth House).[46]

A Gateshead blue plaque honouring William Clarke

A long-running blue plaque scheme is in operation in Gateshead. Run by the council, the scheme was registered with English Heritage in 1970[24] and 29 blue plaques were installed between the inception of the scheme in 1977 and the publication of a commemorative document in 2010.[47][48] The Gateshead scheme aims to highlight notable persons who lived in the borough, notable buildings within it and important historical events.[49] Some of those commemorated through the scheme include Geordie Ridley, author of the Blaydon Races,[50]William Wailes, a noted 19th century proponent of stained glass who lived in a "fairytale mansion" at Saltwell Park,[51][52] the industrialist and co-founder of Clarke Chapman, William Clarke[53] and Sir Joseph Swan, the inventor of the incandescent light bulb whose house in Low Fell was the first in the world to be illuminated by electric light.[53][54]

Further Gateshead blue plaques have since been erected. In 2011 plaques commemorating William Henry Brockett, editor of the first Gateshead newspaper,[55] Dr. Alfred Cox[56] and Sister Winifred Laver, a missionary who had been awarded various decorations, including the British Empire Medal, during her lifetime,[57] were installed. In 2012, further blue plaques were unveiled in commemoration of Vincent Litchfield Raven, an "engineering genius" who was the chief mechanical engineer at the North Eastern Railway where his successes in steam engineering ultimately frustrated his own visionary work on the possibility of electric trains,[58] and the 19th century Felling mining disasters.[59]

In 2017 in Aldershot in Hampshire the Aldershot Civic Society unveiled its first blue plaque to comedian and actor Arthur English at the house where he had been born. It is intended that this will be the first in a series dedicated to notable local people or historic buildings.[60][61][62]

Thematic schemes

There also exist several nationwide schemes sponsored by special-interest bodies, which erect plaques at sites or buildings with historical associations within their particular sphere of activity.

- The Transport Trust's Red Wheel scheme erects red plaques on sites of significance in the evolution of transport.[63]

- The Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America erects blue plaques on sites associated with notable music hall and variety artistes, mainly in the London area.

- The British Comedy Society (previously known as the Dead Comics' Society) erects blue plaques on the former homes of well-known comedians, including those of Sid James and John Le Mesurier.

- The Royal Society of Chemistry's Chemical Landmark Scheme erects hexagonal blue plaques to mark sites where the chemical sciences are considered to have made a significant contribution to health, wealth, or quality of life.[64]

Transport Trust plaque at Hythe Pier and Railway, Hythe, Hampshire, the oldest working pier railway in the world

Royal Society of Chemistry plaque on the Chemistry Department of University College London, recording the work carried out there by Sir Christopher Ingold (erected 2008)

Examples

John Logie Baird: 22 Frith Street, Westminster, London, W1D 4RP

Barry Jackson: The Old Rep Theatre, Station Street, Birmingham, B5 4DY

Roger Bannister: Oxford University Athletics Track, Iffley Road, Oxford, OX4

Herbert Campbell: 44 Lawford Road, Hackney

Charlie Chaplin: 287 Kennington Road, London, SE11

Winston Churchill: 28 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington Gore, Kensington and Chelsea, SW7

Roald Dahl: Mrs Pratchett's former sweet shop in Llandaff, Cardiff commemorating the mischief a young Dahl played on her by putting a mouse in the gobstoppers jar.[65]

Charles Darwin: Biological Sciences Building, University College, Camden, Gower Street, WC1

Charles Dickens: BMA building commemorating his former home Tavistock House, Tavistock Square, London.

Michael Faraday: Larcom Street, Walworth.

Benjamin Franklin (one of the Founding Fathers of the United States) once owned a property in Preston city centre, on the corner of Cheapside and Friargate.

Anna and Sigmund Freud can be found on the Freud Museum, 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, NW3.

Mahatma Gandhi: 20 Baron's Court Road, Hammersmith and Fulham, W14, marks where he stayed while living in London

George Frideric Handel and Jimi Hendrix: side by side on 25 and 23 Brook Street, Mayfair, London, W1.

Alfred Hitchcock: 153 Cromwell Road, London, SW5

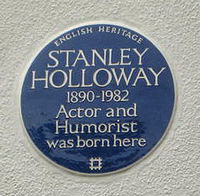

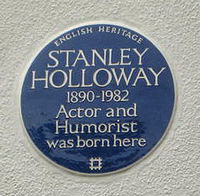

Stanley Holloway: 25 Albany Road, Manor Park, Newham, E12, the house in which he was born.

Sherlock Holmes: 221B Baker Street, London, W1, placed there on behalf of the Sherlock Holmes Museum which now occupies the site.

Cecil Jackson-Cole: Oxfam Charity Shop, 17 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3AS

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Founder of Pakistan): 35 Russell Street, Kensington, London. At the house where he stayed while in London in 1895.

Marie Kendall: Okeover Manor Clapham Common.

T. E. Lawrence: 14 Barton Street Westminster, SW1, and another at 2 Polstead Road, Oxford, OX2, which was his childhood home.

James Legge: 3 Keble Road, Oxford

John Lennon: 251 Menlove Avenue, Liverpool

Bob Marley: Ridgmount Gardens.

Freddie Mercury: 22 Gladstone Avenue in Feltham, west London.[66]

Keith Moon by The Heritage Foundation[67] is situated at 90 Wardour Street, Soho, London, W1F 0UB, site of the Marquee Club

Isaac Newton: 87 Jermyn Street, Westminster, SW1

Laurence Olivier: Wathen Road, Dorking

Fred Perry: 223 Pitshanger Lane, Ealing, London

W. Heath Robinson: 75 Moss Lane, Pinner, Harrow

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Aldwyn Tower, a former hotel in Malvern, Worcestershire, where he stayed while convalescing from an illness during his childhood.

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar: 65 Cromwell Avenue Highgate, London N6, marks where he stayed while living in London

Peter Sellers: Muswell Hill Road, near Highgate Station

Robert Louis Stevenson: Mount Vernon, corner of Holly Place, Hampstead, London, NW3

P. L. Travers: 50 Smith Street, London, SW3

Alan Turing: 2 Warrington Crescent, Maida Vale, Westminster, London, W9, where he was born.

Vincent van Gogh: 87 Hackford Road, Lambeth, SW9

H. G. Wells: 13 Hanover Terrace, Westminster, NW1

Oscar Wilde: 34 Tite Street, Kensington and Chelsea, SW3

Virginia Woolf: 29 Fitzroy Square, London, W1

Blue plaque at 22 Frith Street, Westminster, W1, commemorating Scottish inventor John Logie Baird's first demonstration of the television

English Heritage plaque at 25 Albany Road, Manor Park, Newham commemorating actor Stanley Holloway (erected 2009)

English Heritage plaque at 223 Pitshanger Lane, Ealing, London commemorating Fred Perry

In other countries

Commemorative plaque schemes (not all of them using blue plaques) also exist most notably in the cities of Paris, Rome, Oslo and Dublin.[68]

In the United States, commemorative plaques similar to those used in Europe are called historical markers. These vary in colour and design by state. The National Trust for Historic Preservation or the U.S. government, through the National Register of Historic Places, can bestow historical status, with a small bronze marker affixed to the building. Other markers are erected by state historical commissions and similar authorities, local governments or civic groups. These can also be affixed to the building, but are frequently free-standing markers with the text on each side, or, in larger instances, beginning on one side and continuing to the other.

Most states in Australia have historic marker programs. For example, in Victoria all places and objects listed on the Victorian Heritage Register are entitled to a blue plaque.[69] The Mechanics' Institutes of Victoria Inc. have also adopted a blue plaques program, and more than 30 Mechanics' Institutes throughout the state have installed plaques on their buildings.[70]

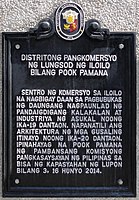

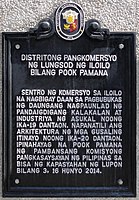

The Philippines have more than 1,500 historical markers installed for numerous personalities, places, structures, and events around the country. There are also a number of ones installed outside the country. The government agency tasked for this is the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), although local government units can also install markers of local significance.[71] The policy of installing markers started in 1933.[72] The initial markers were placed in 1934.

New York State plaque

Michigan Historical Marker, explaining the significance of the Michigan Central Depot building in Battle Creek, Michigan

Norwegian version of blue plaque, set up by Selskabet for Oslo Byes Vel

Philippine historical marker for Calle Real

References

^ abc Spencer, Howard (2008). "The commemoration of historians under the blue plaque scheme in London". Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 16 June 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcdef "The History of Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

^ "Built to last: the making of a blue plaque". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

^ "Blue Plaque FAQS". English Heritage. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

^ "Getting back to where she once belonged: Yoko Ono unveils blue plaque at John Lennon's London home". Daily Mail. London. 23 October 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ Hansard vol 172 17 July 1863 quoted in 'The commemoration of historians under the blue plaque scheme in London' by author Howard Spencer

^ ab "About blue plaques". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

^ ab "The Blue Plaque Design". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

^ ab Quinn, Ben (6 January 2013). "Blue plaques scheme suspended after 34% cut in government funding". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

^ Plaque #473 on Open Plaques.

^ Plaque #136 on Open Plaques.

^ Plaque #604 on Open Plaques.

^ "Blue Plaques scheme position statement". 8 January 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

^ Gray, Louise (7 January 2013). "National Trust could save blue plaques". The Daily Telegraph. London.

^ "London Blue Plaques Re-Open For Nominations – 18 June 2014". English Heritage. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

^ "London Blue Plaques scheme re-launched", Salon: Society of Antiquaries of London Online Newsletter, 322, 23 June 2014, retrieved 27 June 2014

^ abc "Propose a plaque". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

^ "How to propose a Blue Plaque". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Blue Plaques Panel". English Heritage. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

^ Parker, Peter (11 July 2009). "Lived in London: Blue Plaques and the Stories Behind Them by Emily Cole: review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

^ Plaque #517 on Open Plaques.

^ Plaque #1412 on Open Plaques.

^ "About Blue Plaques: Frequently Asked Questions". English Heritage. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

^ ab "Register of Plaque Schemes". English Heritage. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

^ "Blue plaques". City of London. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

^ "Green Plaques Scheme". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Blue Plaque Winners 2007". Southwark Borough Council. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008.

^ "Recent Plaques". London Borough of Islington. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

^ "THe Ulster History Circle". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Poet and broadcaster remembered". 8 February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Birmingham Civic Society plaques list". Retrieved 12 January 2013.

^ "Birmingham Civic Society Awards". Retrieved 29 November 2011.

^ ab "Commemorative Plaques". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Commemorative plaques scheme". Manchester Art Gallery. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

^ "The Portuguese gave us fried fish, the Belgians invented chips but 150 years ago an East End boy united them to create The World's Greatest Double Act". Daily Mail. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

^ "Blue Plaques in Bournemouth". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Blue Plaques of Bournemouth". Bournemouth Borough Council.

^ "The history of Berkhamsted". Berkhamsted Town Council. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

^ Cook, John (2009). A Glimpse of our History: a short guided tour of Berkhamsted (PDF). Berkhamsted Town Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

^ "Blue Plaques". Wolverhampton Civic and Historical Society. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

^ "Loughton Blue Plaques" (PDF). Retrieved 9 August 2016.

^ "Blue plaque link to town's famous faces". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 21 October 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

^ "Plaque a tribute to Narnia author". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 21 July 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

^ "Emperor will be remembered as part of civic week". Malvern Gazette. Newsquest Media Group. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

^ "Final vote for Derbyshire blue plaque honour". BBC News. 25 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

^ "Blue Plaques". Derbyshire County Council. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

^ "Commemorative Plaques". Gateshead Council. 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ Richards, Linda (9 September 2010). "Blue Plaques mapshows off famous spots". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ "Gateshead's Commemorative Plaques" (PDF). Gateshead Council. June 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012. at p.2

^ "Gateshead's Commemorative Plaques" (PDF). Gateshead Council. June 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012. at p.3

^ "Plaque honours famous ex-resident". the BBC. 15 June 2005. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ "Fairytale mansion gets new life". BBC. 14 July 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

^ ab "Gateshead's Commemorative Plaques" (PDF). Gateshead Council. June 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012. at p.8

^ "Gateshead Blue Plaques – Joseph Swan 1828–1914". Gateshead Libraries. 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ Lawson, Ruth (8 March 2011). "Gateshead newspaper founder honoured". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ Richards, Linda (23 March 2011). "Blue plaque marks Victorian medic's home". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ Richards, Linda (23 June 2011). "Blue plaque honour to Sister Winifred Laver". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ Wainwright, Martin (21 March 2012). "Gateshead honours an engineering giant whose genius has lessons for our times". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ "Felling Pit Disaster remembered on 200th anniversary". the BBC. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

^ Blue Plaque for Arthur English – Aldershot Civic Society website

^ 'Are You Being Served? actor Arthur English honoured with blue plaque' – BBC News Online – 15 July 2017

^ 'Blue plaque unveiled for Aldershot's Arthur English' – Eagle Radio – 15 July 2017

^ "Transport Trust". Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

^ "Connecting Everyone with Chemistry". Royal Society of Chemistry.

^ "Blue plaque marks Dahl sweet shop". BBC. Retrieved 24 December 2014

^ "Blue Plaque unveiled on Freddie Mercury's first London home". BBC News. 2 September 2016.

^ "Keith Moon plaque unveiling". Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

^ "Plaques by Country". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

^ "Blue Plaques". Department of Planning and Community Development, Victoria. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

^ "Historical Plaques Program". Mechanics' Institutes of Victoria Inc. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

^ "GUIDELINES_IDENTIF CLASSIF AND RECOG OF HIST SITES & STRUCTS IN THE PHIL.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

^ Historical Markers Placed by the Philippine Historical Committee. Manila: Bureau of Printing. 1958.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Cole, Emily; Stephen Fry (2009). Lived in London: blue plaques and the stories behind them. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14871-8.

Dakers, Caroline (1981). The Blue Plaque Guide to London. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-28462-9.

Ito, Kota (2017). "Municipalization of memorials: progressive politics and the commemoration schemes of the London County Council, 1889–1907". London Journal. 42: 273–90.

Rennison, Nick (2009). The London Blue Plaque Guide (3rd ed.). The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7524-5050-6.

Sumeray, Derek (2003). Track the Plaque: 23 Walks Around London's Commemorative Plaques. Breedon. ISBN 978-1-85983-362-9.

Sumeray, Derek; John Sheppard (2009). London Plaques. Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0735-3.

External links

Wikidata has the property:

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blue plaques. |

Open Plaques open register of historical markers