Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz (Cyrillic: Јосип Броз, pronounced [jǒsip brôːz]; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (/ˈtiːtoʊ/;[1]Cyrillic: Тито, pronounced [tîto]), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and political leader, serving in various roles from 1943 until his death in 1980.[2] During World War II, he was the leader of the Partisans, often regarded as the most effective resistance movement in occupied Europe.[3] While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian[4][5] and concerns about the repression of political opponents have been raised, some historians consider him a benevolent dictator.[6] He was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad.[7] Viewed as a unifying symbol,[8] his internal policies maintained the peaceful coexistence of the nations of the Yugoslav federation. He gained further international attention as the chief leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, alongside Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Sukarno of Indonesia, and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana.[9]

Broz was born to a Croat father and Slovene mother in the village of Kumrovec, Austria-Hungary (now in Croatia). Drafted into military service, he distinguished himself, becoming the youngest sergeant major in the Austro-Hungarian Army of that time. After being seriously wounded and captured by the Imperial Russians during World War I, he was sent to a work camp in the Ural Mountains. He participated in some events of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and subsequent Civil War. Upon his return home, Broz found himself in the newly established Kingdom of Yugoslavia, where he joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ).

He was General Secretary (later Chairman of the Presidium) of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (1939–1980) and went on to lead the World War II Yugoslav guerrilla movement, the Partisans (1941–1945).[10] After the war, he was the Prime Minister (1944–1963), President (later President for Life) (1953–1980) of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). From 1943 to his death in 1980, he held the rank of Marshal of Yugoslavia, serving as the supreme commander of the Yugoslav military, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). With a highly favourable reputation abroad in both Cold War blocs, he received some 98 foreign decorations, including the Legion of Honour and the Order of the Bath.

Tito was the chief architect of the second Yugoslavia, a socialist federation that lasted from November 1942 until April 1992. Despite being one of the founders of Cominform, he became the first Cominform member to defy Soviet hegemony in 1948 and the only one in Joseph Stalin's time to manage to leave Cominform and begin with its own socialist program with elements of market socialism. Economists active in the former Yugoslavia, including Czech-born Jaroslav Vanek and Croat-born Branko Horvat, promoted a model of market socialism dubbed the Illyrian model, where firms were socially owned by their employees and structured on workers' self-management and competed with each other in open and free markets.

Contents

1 Early life

1.1 Pre-World War I

1.2 World War I

2 Interwar communist activity

2.1 Communist agitator

2.2 Professional revolutionary

2.3 Prison

2.4 Flight from Yugoslavia

2.5 General Secretary of the CPY

3 World War II

3.1 Resistance in Yugoslavia

3.2 Aftermath

4 Presidency

4.1 Tito–Stalin split

4.2 Non-Alignment

4.3 Reforms

5 Evaluation

6 Final years

7 Legacy

8 Family and personal life

8.1 Language and identity dispute

8.2 Origin of the name "Tito"

9 Awards and decorations

9.1 Domestic awards

9.2 Foreign awards

10 See also

11 Notes

12 Footnotes

13 Bibliography

14 Further reading

15 External links

Early life

Pre-World War I

Josip Broz was born on 7 May 1892 in Kumrovec, a village in the northern Croatian region of Hrvatsko Zagorje which at that time was part of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia within the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[a][b]

He was the seventh or eighth child of Franjo Broz (1860–1936) and Marija née Javeršek (1864–1918), his parents having already lost a number of children in early infancy.[13][14] He was christened and raised as a Roman Catholic.[15] His father, Franjo, was a Croat whose family had lived in the village for three centuries, while his mother Marija, was a Slovene from the village of Podsreda. The villages were only 16 kilometres (10 mi) apart, and his parents had been married on 21 January 1881. Franjo Broz had inherited a 4.0-hectare (10-acre) estate and a good house, but he was unable to make a success of farming. Josip spent a significant proportion of his pre-school years living with his maternal grandparents at Podsreda, where he became a favourite of his grandfather Martin Javeršek, and by the time he returned to Kumrovec to commence school he spoke Slovene better than Croatian,[16][17] and had learned to play the piano.[18] Despite his mixed parentage, Broz is often referred to as an ethnic Croat.[19][20][21]

In July 1900,[18] at the age of eight, Broz entered primary school at Kumrovec, but only completed four years of school,[17] failing the 2nd grade then graduating in 1905.[16] As a result of his limited schooling, throughout his life he was poor at spelling. After leaving school, he initially worked for a maternal uncle then on the family farm.[17] In 1907, his father wanted him to emigrate to the United States, but could not raise the money for the voyage.[22] Instead, aged 15 years, Josip left Kumrovec and travelled about 97 kilometres (60 mi) south to Sisak where his cousin Jurica Broz was doing army service. Jurica helped him get a job in a restaurant, but Broz soon tired of that work and approached a Czech locksmith, Nikola Karas, for a three-year apprenticeship, which included training, food, and room and board. As his father could not afford to pay for his work clothing, Josip paid for it himself. Soon after, his younger brother Stjepan also became apprenticed to Karas.[16][23]

During his apprenticeship he was encouraged to mark May Day in 1909, and read and sold Slobodna Reč (Free Word), a socialist newspaper. After completing his apprenticeship in September 1910, Broz used his contacts to gain employment in Zagreb and at the age of 18 joined the Metal Workers' Union and participated in his first labour protest.[24] He also joined the Social-Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia.[25]

He returned home in December 1910[26] and in early 1911 began a series of moves, first seeking work in Ljubljana then Trieste, Kumrovec and Zagreb, where he worked repairing bicycles and joined his first strike action on May Day 1911.[24] After a brief period of work in Ljubljana,[26] between May 1911 and May 1912 he worked in a factory in Kamnik in the Kamnik–Savinja Alps, and when it closed, he was offered redeployment to Čenkov in Bohemia. On arriving at his new workplace he discovered that the employer was trying to bring in cheaper labour to replace the local Czech workers, and he and others joined successful strike action to force the employer to back down.[c]

Driven by curiosity, Broz then moved to Plzeň where he was briefly employed at the Škoda Works, then travelled to Munich in Bavaria. He also worked at the Benz car factory in Mannheim, and visited the Ruhr. By October 1912 he had arrived in Vienna where he stayed with his older brother Martin and his family and worked at the Griedl Works before getting a job at Wiener Neustadt where he worked for Austro-Daimler, and was often asked to drive and test the cars.[28] During this time he spent considerable time fencing and dancing,[29][30] and during his training and early work life he also learned German and passable Czech.[31][d]

World War I

In May 1913,[31] Broz was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army,[33][e] for his compulsory two years of service. He successfully requested that he serve with the 25th Croatian Home Guard (Croatian: Domobran) Regiment garrisoned in Zagreb. After learning to ski during the winter of 1913–1914, he was sent to a school for non-commissioned officers in Budapest,[35] after which he was promoted to sergeant major, and, at 22 years of age, became the youngest of that rank in his regiment.[31][35][f] At least one source states that he was also the youngest sergeant major in the Austro-Hungarian Army.[37] After winning the regimental fencing competition,[35] Broz went on to come second in the army fencing championships in Budapest in May 1914.[37]

Soon after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the 25th Croatian Home Guard Regiment marched towards the Serbian border, but Broz was arrested for sedition and imprisoned in the Petrovaradin fortress in present-day Novi Sad.[38] Broz later gave conflicting accounts of this arrest, telling one biographer that he had threatened to desert to the Russians, but also claiming that the whole matter arose from a clerical error.[35] A third version was that he had been overheard saying that he hoped the Austro-Hungarian Empire would be defeated. After his acquittal and release,[39] his regiment served briefly on the Serbian Front before being deployed to the Eastern Front in Galicia in early 1915 to fight against Russia.[35] On one occasion, the scout platoon he commanded went behind the enemy lines and captured 80 Russian soldiers, bringing them back to their own lines alive. In 1980 it was discovered that he had been recommended for an award for gallantry and initiative in reconnaissance and capturing prisoners.[40] On 25 March 1915,[g] he was wounded in the back by a Circassian cavalryman's lance,[42] and captured during a Russian attack near Bukovina.[43] Now a prisoner of war (POW), Broz was transported east to a hospital established in an old monastery in the town of Sviyazhsk on the Volga river near Kazan.[35] During his 13 months in hospital he had bouts of pneumonia and typhus, and learned Russian with the help of two schoolgirls who brought him Russian classics by such authors as Tolstoy and Turgenev to read.[35][41][44]

After recuperating, in mid-1916 he was transferred to the Ardatov POW camp in the Samara Governorate, where he used his skills to maintain the nearby village grain mill. At the end of the year, he was again transferred, this time to the Kungur POW camp near Perm where the POWs were used as labour to maintain the newly completed Trans-Siberian Railway.[35] Broz was appointed to be in charge of all the POWs in the camp.[45] During this time he became aware that the Red Cross parcels sent to the POWs were being stolen by camp staff. When he complained, he was beaten and put in prison.[35] During the February Revolution, a crowd broke into the prison and returned Broz to the POW camp. A Bolshevik he had met while working on the railway told Broz that his son was working in an engineering works in Petrograd, so, in June 1917, Broz walked out of the unguarded POW camp and hid aboard a goods train bound for that city, where he stayed with his friend's son.[46][47] The journalist Richard West has suggested that because Broz chose to remain in an unguarded POW camp rather than volunteer to serve with the Yugoslav legions of the Serbian Army, this indicates that he remained loyal to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and undermines his later claim that he and other Croat POWs were excited by the prospect of revolution and looked forward to the overthrow of the empire that ruled them.[48]

Less than a month after Broz arrived in Petrograd, the July Days demonstrations broke out, and Broz joined in, coming under fire from government troops.[49][50] In the aftermath, he tried to flee to Finland in order to make his way to the United States, but was stopped at the border.[51] He was arrested along with other suspected Bolsheviks during the subsequent crackdown by the Russian Provisional Government led by Alexander Kerensky. He was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress for three weeks, during which he claimed to be an innocent citizen of Perm. When he finally admitted to being an escaped POW, he was to be returned by train to Kungur, but escaped at Yekaterinburg, then caught another train which reached Omsk in Siberia on 8 November after a 3,200-kilometre (2,000 mi) journey.[49][52] At one point, police searched the train looking for an escaped POW, but were deceived by Broz's fluent Russian.[50]

In Omsk the train was stopped by local Bolsheviks who told Broz that Vladimir Lenin had seized control of Petrograd. They recruited him into an International Red Guard which guarded the Trans-Siberian Railway during the winter of 1917–1918. In May 1918, the anti-Bolshevik Czechoslovak Legion wrested control of parts of Siberia from Bolshevik forces, and the Provisional Siberian Government established itself in Omsk, and Broz and his comrades went into hiding. At this time Broz met a beautiful 14-year-old local girl, Pelagija "Polka" Belousova, who hid him then helped him escape to a Kyrgyz village 64 kilometres (40 mi) from Omsk.[49][53] Broz again worked maintaining the local mill until November 1919 when the Red Army recaptured Omsk from White forces loyal to the Provisional All-Russian Government of Alexander Kolchak. He moved back to Omsk and married Belousova in January 1920.[h] At the time of their marriage, Broz was 27 years old and Belousova was 15.[55] In the autumn of 1920 he and his pregnant wife returned to his homeland, first by train to Narva, by ship to Stettin, then by train to Vienna, where they arrived on 20 September. In early October Broz returned home to Kumrovec in what was then the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to find that his mother had died and his father had moved to Jastrebarsko near Zagreb.[49] Sources differ over whether Broz joined the Communist Party while in Russia, but he stated that the first time he joined the party was in Zagreb after he returned to his homeland.[56]

Interwar communist activity

Communist agitator

The assassination of Milorad Drašković led to the outlawing of the Communist Party

Upon his return home, Broz was unable to gain employment as a metalworker in Kumrovec, so he and his wife moved briefly to Zagreb, where he worked as a waiter, and took part in a waiter's strike. He also joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY).[57] The CPY's influence on the political life of Yugoslavia was growing rapidly. In the 1920 elections it won 59 seats and became the third strongest party.[58] After the assassination of Milorad Drašković, the Yugoslav Minister of the Interior, by a young communist named Alija Alijagić on 2 August 1921, the CPY was declared illegal under the Yugoslav State Security Act of 1921.[59]

Due to his overt communist links, Broz was fired from his employment.[60] He and his wife then moved to the village of Veliko Trojstvo where he worked as a mill mechanic.[61][62] After the arrest of the CPY leadership in January 1922, Stevo Sabić took over control of its operations. Sabić contacted Broz who agreed to work illegally for the party, distributing leaflets and agitating among factory workers. In the contest of ideas between those that wanted to pursue moderate policies and those that advocated violent revolution, Broz sided with the latter. In 1924, Broz was elected to the CPY district committee, but after he gave a speech at a comrade's Catholic funeral he was arrested when the priest complained. Paraded through the streets in chains, he was held for eight days and was eventually charged with creating a public disturbance. With the help of a Serbian Orthodox prosecutor who hated Catholics, Broz and his co-accused were acquitted.[63] His brush with the law had marked him as a communist agitator, and his home was searched on an almost weekly basis. Since their arrival in Yugoslavia, Pelagija had lost three babies soon after their births, and one daughter, Zlatina, at the age of two. Broz felt the loss of Zlatina deeply. In 1924, Pelagija gave birth to a boy, Žarko, who survived. In mid-1925, Broz's employer died and the new mill owner gave him an ultimatum, give up his communist activities or lose his job. So, at the age of 33, Broz became a professional revolutionary.[64][65]

Professional revolutionary

The CPY concentrated its revolutionary efforts on factory workers in the more industrialised areas of Croatia and Slovenia, encouraging strikes and similar action.[66] In 1925, the now unemployed Broz moved to Kraljevica on the Adriatic coast, where he started working at a shipyard to further the aims of the CPY.[67] While at Kraljevica he worked on Yugoslav torpedo boats and a pleasure yacht for the People's Radical Party politician, Milan Stojadinović. Broz built up the trade union organisation in the shipyards and was elected as a union representative. A year later he led a shipyard strike, and soon after was fired. In October 1926 he obtained work in a railway works in Smederevska Palanka near Belgrade. In March 1927, he wrote an article complaining about the exploitation of workers in the factory, and after speaking up for a worker he was promptly sacked. Identified by the CPY as worthy of promotion, he was appointed secretary of the Zagreb branch of the Metal Workers' Union, and soon after of the whole Croatian branch of the union. In July 1927 Broz was arrested, along with six other workers, and imprisoned at nearby Ogulin.[68][69] After being held without trial for some time, Broz went on a hunger strike until a date was set. The trial was held in secret and he was found guilty of being a member of the CPY. Sentenced to four months' imprisonment, he was released from prison pending an appeal. On the orders of the CPY, Broz did not report to the court for the hearing of the appeal, instead going into hiding in Zagreb. Wearing dark spectacles and carrying forged papers, Broz posed as a middle-class technician in the engineering industry, working undercover to contact other CPY members and coordinate their infiltration of trade unions.[70]

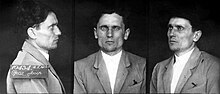

Tito's mug shot after arrest for communist activities in 1928

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, Broz condemned factions within the party. These included those that advocated a Greater Serbia agenda within Yugoslavia, like the long-term CPY leader, the Serb Sima Marković. Broz proposed that the executive committee of the Communist International purge the branch of factionalism, and was supported by a delegate sent from Moscow. After it was proposed that the entire central committee of the Croatian branch be dismissed, a new central committee was elected with Broz as its secretary.[71] Marković was subsequently expelled from the CPY at the Fourth Congress of the Comintern, and the CPY adopted a policy of working for the break-up of Yugoslavia.[72] Broz arranged to disrupt a meeting of the Social-Democratic Party on May Day that year, and in a melee outside the venue, Broz was arrested by the police. They failed to identify him, charging him under his false name for a breach of the peace. He was imprisoned for 14 days and then released, returning to his previous activities.[73] The police eventually tracked him down with the help of a police informer. He was ill-treated and held for three months before being tried in court in November 1928 for his illegal communist activities,[74] which included allegations that the bombs that had been found at his address had been planted by the police.[75] He was convicted and sentenced to five years' imprisonment.[76]

Prison

Tito (left) and his ideological mentor Moša Pijade while in the Lepoglava jail

After his sentencing, his wife and son returned to Kumrovec, where they were looked after by sympathetic locals, but then one day they suddenly left without explanation and returned to the Soviet Union.[77] She fell in love with another man and Žarko grew up in institutions.[78] After arriving at Lepoglava prison, Broz was employed in maintaining the electrical system, and chose as his assistant a middle-class Belgrade Jew, Moša Pijade, who had been given a 20-year sentence for his communist activities. Their work allowed Broz and Pijade to move around the prison, contacting and organising other communist prisoners.[79] During their time together in Lepoglava, Pijade became Broz's ideological mentor.[80] After two and a half years at Lepoglava, Broz was accused of attempting to escape and was transferred to Maribor prison where he was held in solitary confinement for several months.[81] After completing the full term of his sentence, he was released, only to be arrested outside the prison gates and taken to Ogulin to serve the four-month sentence he had avoided in 1927. He was finally released from prison on 16 March 1934, but even then he was subject to orders that required him to live in Kumrovec and report to the police daily.[82] During his imprisonment, the political situation in Europe had changed significantly, with the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany and the emergence of right-wing parties in France and neighbouring Austria. He returned to a warm welcome in Kumrovec, but did not stay for long. In early May, he received word from the CPY to return to his revolutionary activities, and left his home town for Zagreb, where he rejoined the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia.[83]

The Croatian branch of the CPY was in disarray, a situation exacerbated by the escape of the executive committee of the CPY to Vienna in Austria, from which they were directing activities. Over the next six months, Broz travelled several times between Zagreb, Ljubljana and Vienna, using false passports. In July 1934, he was blackmailed by a smuggler, but pressed on across the border, and was detained by the local Heimwehr, a paramilitary Home Guard. He used the Austrian accent he had developed during his war service to convince them that he was a wayward Austrian mountaineer, and they allowed him to proceed to Vienna.[84][85] Once there, he contacted the General Secretary of the CPY, Milan Gorkić, who sent him to Ljubljana to arrange a secret conference of the CPY in Slovenia. The conference was held at the summer palace of the Roman Catholic bishop of Ljubljana, whose brother was a communist sympathiser. It was at this conference that Broz first met Edvard Kardelj, a young Slovene communist who had recently been released from prison. Broz and Kardelj subsequently became good friends, with Tito later regarding him as his most reliable deputy. As he was wanted by the police for failing to report to them in Kumrovec, Broz adopted various pseudonyms, including "Rudi" and "Tito". He used the latter as a pen name when he wrote articles for party journals in 1934, and it stuck. He gave no reason for choosing the name "Tito" except that it was a common nickname for men from the district where he grew up. Within the Comintern network, his nickname was "Walter".[86][87][88]

Flight from Yugoslavia

Edvard Kardelj met Tito in 1934 and they became good friends

During this time Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when King Alexander was assassinated by the Croatian nationalist Ustaše organisation in Marseilles on 9 October 1934. In the crackdown on dissidents that followed his death, it was decided that Tito should leave Yugoslavia. He travelled to Vienna on a forged Czech passport where he joined Gorkić and the rest of the Politburo of the CPY. It was decided that the Austrian government was too hostile to communism, so the Politburo travelled to Brno in Czechoslovakia, and Tito accompanied them.[89] On Christmas Day 1934, a secret meeting of the Central Committee of the CPY was held in Ljubljana, and Tito was elected as a member of the Politburo for the first time. The Politburo decided to send him to Moscow to report on the situation in Yugoslavia, and in early February 1935 he arrived there as full-time official of the Comintern.[90] He lodged at the main Comintern residence, the Hotel Lux on Tverskaya Street, and was quickly in contact with Vladimir Ćopić, one of the leading Yugoslavs with the Comintern. He was soon introduced to the main personalities in the organisation. Tito was appointed to the secretariat of the Balkan section, responsible for Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania and Greece.[91] Kardelj was also in Moscow, as was the Bulgarian communist leader Georgi Dimitrov.[87] Tito lectured on trade unions to foreign communists, and attended a course on military tactics run by the Red Army, and occasionally attended the Bolshoi Theatre. He attended as one of 510 delegates to the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern in July and August 1935, where he briefly saw Joseph Stalin for the first time. After the congress, he toured the Soviet Union, then returned to Moscow to continue his work. He contacted Polka and Žarko, but soon fell in love with an Austrian woman who worked at the Hotel Lux, Johanna Koenig, known within communist ranks as Lucia Bauer. When she became aware of this liaison, Polka divorced Tito in April 1936. Tito married Bauer on 13 October of that year.[92]

After the World Congress, Tito worked to promote the new Comintern line on Yugoslavia, which was that it would no longer work to break up the country, and would instead defend the integrity of Yugoslavia against Nazism and Fascism. From a distance, Tito also worked to organise strikes at the shipyards at Kraljevica and the coal mines at Trbovlje near Ljubljana. He tried to convince the Comintern that it would be better if the party leadership was located inside Yugoslavia. A compromise was arrived at, where Tito and others would work inside the country and Gorkić and the Politburo would continue to work from abroad. Gorkić and the Politburo relocated to Paris, while Tito began to travel between Moscow, Paris and Zagreb in 1936 and 1937, using false passports.[93] In 1936, his father died.[16]

Yugoslav volunteers fighting in the Spanish Civil War

Tito returned to Moscow in August 1936, soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.[94] At the time, the Great Purge was underway, and foreign communists like Tito and his Yugoslav compatriots were particularly vulnerable. Despite a laudatory report written by Tito about the veteran Yugoslav communist Filip Filipović, he was arrested and shot by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD.[95] However, before the Purge really began to erode the ranks of the Yugoslav communists in Moscow, Tito was sent back to Yugoslavia with a new mission, to recruit volunteers for the International Brigades being raised to fight on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. Travelling via Vienna, he reached the coastal port city of Split in December 1936.[96] According to the Croatian historian Ivo Banac, the reason Tito was sent back to Yugoslavia by the Comintern was in order to purge the CPY.[97] An initial attempt to send 500 volunteers to Spain by ship failed utterly, with nearly all the communist volunteers being arrested and imprisoned.[96] Tito then travelled to Paris, where he arranged the travel of volunteers to France under the cover of attending the Paris Exhibition. Once in France, the volunteers simply crossed the Pyrenees to Spain. In all, he sent 1,192 men to fight in the war, but only 330 came from Yugoslavia, the rest being expatriates in France, Belgium, the US and Canada. Less than half were communists, and the rest were social-democrats and anti-fascists of various hues. Of the total, 671 were killed in the fighting and another 300 were wounded. Tito himself never went to Spain, despite later claims that he had. Between May and August 1937, Tito travelled several times between Paris and Zagreb organising the movement of volunteers and creating a separate Communist Party of Croatia. The new party was inaugurated at a conference at Samobor on the outskirts of Zagreb on 1–2 August 1937.[98]

General Secretary of the CPY

In June 1937, Gorkić was summoned to Moscow, where he was arrested, and after months of NKVD interrogation, he was shot.[99] According to Banac, Gorkić was killed on Stalin's orders.[97] West concludes that despite being in competition with men like Gorkić for the leadership of the CPY, it was not in Tito's character to have innocent people sent to their deaths.[100] Tito then received a message from the Politburo of the CPY to join them in Paris. In August 1937 he became acting General Secretary of the CPY. He later explained that he survived the Purge by staying out of Spain where the NKVD was active, and also by avoiding visiting the Soviet Union as much as possible. When first appointed as general secretary, he avoided travelling to Moscow by insisting that he needed to deal with some indiscipline in the CPY in Paris. He also promoted the idea that the upper echelons of the CPY should be sharing the dangers of underground resistance within the country.[101] He developed a new, younger leadership team that was loyal to him, including the Slovene Kardelj, the Serb, Aleksandar Ranković, and the Montenegrin, Milovan Đilas.[102] In December 1937, Tito arranged for a demonstration to greet the French foreign minister when he visited Belgrade, expressing solidarity with the French against Nazi Germany. The protest march numbered 30,000 and turned into a protest against the neutrality policy of the Stojadinović government. It was eventually broken up by the police. In March 1938 Tito returned to Yugoslavia from Paris. Hearing a rumour that his opponents within the CPY had tipped off the police, he travelled to Belgrade rather than Zagreb and used a different passport. While in Belgrade he stayed with a young intellectual, Vladimir Dedijer, who was a friend of Đilas. Arriving in Yugoslavia a few days ahead of the Anschluss between Nazi Germany and Austria, he made an appeal condemning it, in which the CPY was joined by the Social Democrats and trade unions. In June, Tito wrote to the Comintern suggesting that he should visit Moscow. He waited in Paris for two months for his Soviet visa before travelling to Moscow via Copenhagen. He arrived in Moscow on 24 August.[103]

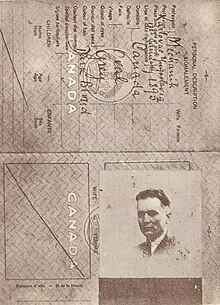

Fake Canadian ID, "Spiridon Mekas", used for returning to Yugoslavia from Moscow, 1939

On arrival in Moscow, he found that all Yugoslav communists were under suspicion. Nearly all the most prominent leaders of the CPY were arrested by the NKVD and executed, including over twenty members of the Central Committee. Both his ex-wife Polka and his wife Koenig/Bauer were arrested as "imperialist spies", although they were both eventually released, Polka after 27 months in prison. Tito therefore needed to make arrangements for the care of Žarko, who was fourteen. He placed him a boarding school outside Kharkov, then at a school at Penza, but he ran away twice and was eventually taken in by a friend's mother. In 1941, Žarko joined the Red Army to fight the invading Germans.[104] Some of Tito's critics argue that his survival indicates he must have denounced his comrades as Trotskyists. He was asked for information on a number of his fellow Yugoslav communists, but according to his own statements and published documents, he never denounced anyone, usually saying he did not know them. In one case he was asked about the Croatian communist leader Horvatin, but wrote ambiguously, saying that he did not know whether he was a Trotskyist. Nevertheless, Horvatin was not heard of again. While in Moscow, he was given the task of assisting Ćopić to translate the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) into Serbo-Croatian, but they had only got to the second chapter when Ćopić too was arrested and executed. He worked on with a fellow surviving Yugoslav communist, but a Yugoslav communist of German ethnicity reported an inaccurate translation of a passage and claimed it showed Tito was a Trotskyist. Other influential communists vouched for him, and he was exonerated. He was denounced by a second Yugoslav communist, but the action backfired and his accuser was arrested. Several factors were at play in his survival; working class origins, lack of interest in intellectual arguments about socialism, attractive personality and capacity for making influential friends.[105]

While Tito was avoiding arrest in Moscow, Germany was placing pressure on Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland. In response to this threat, Tito organised for a call for Yugoslav volunteers to fight for Czechoslovakia, and thousands of volunteers came to the Czechoslovak embassy in Belgrade to offer their services. Despite the eventual Munich Agreement and Czechoslovak acceptance of the annexation and the fact that the volunteers were turned away, Tito claimed credit for the Yugoslav response, which worked in his favour. By this stage, Tito was well aware of the realities in the Soviet Union, later stating that he "witnessed a great many injustices", but was too heavily invested in communism and too loyal to the Soviet Union to step back at this point.[106] Tito's appointment as General Secretary of the CPY was formally ratified by the Comintern on 5 January 1939.[107]

He was appointed to the Committee and started to appoint allies to him, among them Edvard Kardelj, Milovan Đilas, Aleksandar Ranković and Boris Kidrič.

World War II

Resistance in Yugoslavia

On 6 April 1941, German forces, with Hungarian and Italian assistance, launched an invasion of Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941, Slavko Kvaternik proclaimed the Independent State of Croatia, and Tito responded by forming a Military Committee within the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party.[108] Attacked from all sides, the armed forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia quickly crumbled. On 17 April 1941, after King Peter II and other members of the government fled the country, the remaining representatives of the government and military met with the German officials in Belgrade. They quickly agreed to end military resistance. On 1 May 1941, Tito issued a pamphlet calling on the people to unite in a battle against the occupation.[109] On 27 June 1941, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia appointed Tito Commander in Chief of all project national liberation military forces. On 1 July 1941, the Comintern sent precise instructions calling for immediate action.[110]

Tito and Ivan Ribar at Sutjeska in 1943

Despite conflicts with the rival monarchic Chetnik movement, Tito's Partisans succeeded in liberating territory, notably the "Republic of Užice". During this period, Tito held talks with Chetnik leader Draža Mihailović on 19 September and 27 October 1941.[111] It is said that Tito ordered his forces to assist escaping Jews, and that more than 2,000 Jews fought directly for Tito.[112]

On 21 December 1941, the Partisans created the First Proletarian Brigade (commanded by Koča Popović) and on 1 March 1942, Tito created the Second Proletarian Brigade.[113] In liberated territories, the Partisans organised People's Committees to act as civilian government. The Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) convened in Bihać on 26–27 November 1942 and in Jajce on 29 November 1943.[114] In the two sessions, the resistance representatives established the basis for post-war organisation of the country, deciding on a federation of the Yugoslav nations. In Jajce, a 67-member "presidency" was elected and established a nine-member National Committee of Liberation (five communist members) as a de facto provisional government.[115] Tito was named President of the National Committee of Liberation.[116]

With the growing possibility of an Allied invasion in the Balkans, the Axis began to divert more resources to the destruction of the Partisans main force and its high command.[117] This meant, among other things, a concerted German effort to capture Josip Broz Tito personally. On 25 May 1944, he managed to evade the Germans after the Raid on Drvar (Operation Rösselsprung), an airborne assault outside his Drvar headquarters in Bosnia.[117]

Tito and the Partisan Supreme Command, May 1944

After the Partisans managed to endure and avoid these intense Axis attacks between January and June 1943, and the extent of Chetnik collaboration became evident, Allied leaders switched their support from Draža Mihailović to Tito. King Peter II, American President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in officially recognising Tito and the Partisans at the Tehran Conference.[118] This resulted in Allied aid being parachuted behind Axis lines to assist the Partisans. On 17 June 1944 on the Dalmatian island of Vis, the Treaty of Vis (Viški sporazum) was signed in an attempt to merge Tito's government (the AVNOJ) with the government in exile of King Peter II.[119] The Balkan Air Force was formed in June 1944 to control operations that were mainly aimed at aiding his forces.[120]

On 12 September 1944, King Peter II called on all Yugoslavs to come together under Tito's leadership and stated that those who did not were "traitors",[121] by which time Tito was recognized by all Allied authorities (including the government-in-exile) as the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, in addition to commander-in-chief of the Yugoslav forces. On 28 September 1944, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) reported that Tito signed an agreement with the Soviet Union allowing "temporary entry" of Soviet troops into Yugoslav territory which allowed the Red Army to assist in operations in the northeastern areas of Yugoslavia.[122] With their strategic right flank secured by the Allied advance, the Partisans prepared and executed a massive general offensive which succeeded in breaking through German lines and forcing a retreat beyond Yugoslav borders. After the Partisan victory and the end of hostilities in Europe, all external forces were ordered off Yugoslav territory.

In the final days of World War II in Yugoslavia, units of the Partisans were responsible for atrocities after the repatriations of Bleiburg, and accusations of culpability were later raised at the Yugoslav leadership under Tito. At the time, according to some authors, Josip Broz Tito repeatedly issued calls for surrender to the retreating column, offering amnesty and attempting to avoid a disorderly surrender.[123] On 14 May he dispatched a telegram to the supreme headquarters Slovene Partisan Army prohibiting the execution of prisoners of war and commanding the transfer of the possible suspects to a military court.[124]

Aftermath

Celebrating Tito in Zagreb in 1945, in presence of Orthodox dignitaries, the Catholic cardinal Aloysius Stepinac, and the Soviet military attaché

On 7 March 1945, the provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (Demokratska Federativna Jugoslavija, DFY) was assembled in Belgrade by Josip Broz Tito, while the provisional name allowed for either a republic or monarchy. This government was headed by Tito as provisional Yugoslav Prime Minister and included representatives from the royalist government-in-exile, among others Ivan Šubašić. In accordance with the agreement between resistance leaders and the government-in-exile, post-war elections were held to determine the form of government. In November 1945, Tito's pro-republican People's Front, led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, won the elections with an overwhelming majority, the vote having been boycotted by monarchists.[125] During the period, Tito evidently enjoyed massive popular support due to being generally viewed by the populace as the liberator of Yugoslavia.[126] The Yugoslav administration in the immediate post-war period managed to unite a country that had been severely affected by ultra-nationalist upheavals and war devastation, while successfully suppressing the nationalist sentiments of the various nations in favor of tolerance, and the common Yugoslav goal. After the overwhelming electoral victory, Tito was confirmed as the Prime Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the DFY. The country was soon renamed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) (later finally renamed into Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFRY). On 29 November 1945, King Peter II was formally deposed by the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly. The Assembly drafted a new republican constitution soon afterwards.

Josip Broz Tito and Winston Churchill in 1944 in Naples, Italy

Yugoslavia organized the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslavenska narodna armija, or JNA) from the Partisan movement and became the fourth strongest army in Europe at the time.[127] The State Security Administration (Uprava državne bezbednosti/sigurnosti/varnosti, UDBA) was also formed as the new secret police, along with a security agency, the Department of People's Security (Organ Zaštite Naroda (Armije), OZNA). Yugoslav intelligence was charged with imprisoning and bringing to trial large numbers of Nazi collaborators; controversially, this included Catholic clergymen due to the widespread involvement of Croatian Catholic clergy with the Ustaša regime. Draža Mihailović was found guilty of collaboration, high treason and war crimes and was subsequently executed by firing squad in July 1946.

Prime Minister Josip Broz Tito met with the president of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia, Aloysius Stepinac on 4 June 1945, two days after his release from imprisonment. The two could not reach an agreement on the state of the Catholic Church. Under Stepinac's leadership, the bishops' conference released a letter condemning alleged Partisan war crimes in September, 1945. The following year Stepinac was arrested and put on trial. In October 1946, in its first special session for 75 years, the Vatican excommunicated Tito and the Yugoslav government for sentencing Stepinac to 16 years in prison on charges of assisting Ustaše terror and of supporting forced conversions of Serbs to Catholicism.[128] Stepinac received preferential treatment in recognition of his status[129] and the sentence was soon shortened and reduced to house-arrest, with the option of emigration open to the archbishop. At the conclusion of the "Informbiro period", reforms rendered Yugoslavia considerably more religiously liberal than the Eastern Bloc states.

In the first post war years Tito was widely considered a communist leader very loyal to Moscow, indeed, he was often viewed as second only to Stalin in the Eastern Bloc. In fact, Stalin and Tito had an uneasy alliance from the start, with Stalin considering Tito too independent.

During the immediate post-war period Tito's Yugoslavia had a strong commitment to orthodox Marxist ideas. Harsh repressive measures against dissidents were common, including "arrests, show trials, forced collectivisation, suppression of churches and religion".[130]

Presidency

Tito–Stalin split

Josip Broz Tito greeting former American first lady Eleanor Roosevelt during her July 1953 visit

Kardelj, Ranković and Tito in 1958

Josip Broz Tito visiting his birthplace Kumrovec in 1961

Unlike other new communist states in east-central Europe, Yugoslavia liberated itself from Axis domination with limited direct support from the Red Army. Tito's leading role in liberating Yugoslavia not only greatly strengthened his position in his party and among the Yugoslav people, but also caused him to be more insistent that Yugoslavia had more room to follow its own interests than other Bloc leaders who had more reasons to recognize Soviet efforts in helping them liberate their own countries from Axis control. Although Tito was formally an ally of Stalin after World War II, the Soviets had set up a spy ring in the Yugoslav party as early as 1945, giving way to an uneasy alliance.[citation needed]

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, there occurred several armed incidents between Yugoslavia and the Western Allies. Following the war, Yugoslavia acquired the Italian territory of Istria as well as the cities of Zadar and Rijeka. Yugoslav leadership was looking to incorporate Trieste into the country as well, which was opposed by the Western Allies. This led to several armed incidents, notably attacks by Yugoslav fighter planes on US transport aircraft, causing bitter criticism from the West. From 1945 to 1948, at least four US aircraft were shot down.[citation needed] Stalin was opposed to these provocations, as he felt the USSR unready to face the West in open war so soon after the losses of World War II and at the time when US had operational nuclear weapons whereas the USSR had yet to conduct its first test. In addition, Tito was openly supportive of the Communist side in the Greek Civil War, while Stalin kept his distance, having agreed with Churchill not to pursue Soviet interests there, although he did support the Greek communist struggle politically, as demonstrated in several assemblies of the UN Security Council. In 1948, motivated by the desire to create a strong independent economy, Tito modeled his economic development plan independently from Moscow, which resulted in a diplomatic escalation followed by a bitter exchange of letters in which Tito wrote that "We study and take as an example the Soviet system," but develop it a different form.[citation needed]

The Soviet answer on 4 May admonished Tito and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) for failing to admit and correct its mistakes, and went on to accuse them of being too proud of their successes against the Germans, maintaining that the Red Army had saved them from destruction. Tito's response on 17 May suggested that the matter be settled at the meeting of the Cominform to be held that June. However, Tito did not attend the second meeting of the Cominform, fearing that Yugoslavia was to be openly attacked. In 1949 the crisis nearly escalated into an armed conflict, as Hungarian and Soviet forces were massing on the northern Yugoslav frontier.[131] On 28 June, the other member countries expelled Yugoslavia, citing "nationalist elements" that had "managed in the course of the past five or six months to reach a dominant position in the leadership" of the CPY. The assumption in Moscow was that once it was known that he had lost Soviet approval, Tito would collapse; 'I will shake my little finger and there will be no more Tito,' Stalin remarked.[132] The expulsion effectively banished Yugoslavia from the international association of socialist states, while other socialist states of Eastern Europe subsequently underwent purges of alleged "Titoists". Stalin took the matter personally and arranged several assassination attempts on Tito, none of which succeeded. In a correspondence between the two leaders, Tito openly wrote:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Stop sending people to kill me. We've already captured five of them, one of them with a bomb and another with a rifle. [...] If you don't stop sending killers, I'll send one to Moscow, and I won't have to send a second.

— Josip Broz Tito[133]

One significant consequence of the tension arising between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, was Tito's decision to begin a large scale repression against any real or alleged opponent of his own view of Yugoslavia. This repression was not limited to known and alleged Stalinists, but included also members of the Communist Party or anyone exhibiting sympathy towards the Soviet Union. Prominent partisans, such as Vlado Dapčević and Dragoljub Mićunović, were victims of this period of strong repression which lasted until 1956 and was marked by significant violations of human rights.[134][135] Tens of thousands of political opponents served in forced labour camps, such as Goli Otok,[136] and hundreds died.

Tito with North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh in Belgrade, 1957

Tito's estrangement from the USSR enabled Yugoslavia to obtain US aid via the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), the same US aid institution which administered the Marshall Plan. Still, he did not agree to align with the West, which was a common consequence of accepting American aid at the time. After Stalin's death in 1953, relations with the USSR were relaxed, and Tito began to receive aid as well from the COMECON. In this way, Tito played East-West antagonism to his advantage. Instead of choosing sides, he was instrumental in kick-starting the Non-Aligned Movement, which would function as a 'third way' for countries interested in staying outside of the East-West divide.[9]

The event was significant not only for Yugoslavia and Tito, but also for the global development of socialism, since it was the first major split between Communist states, casting doubt on Comintern's claims for socialism to be a unified force that would eventually control the whole world, as Tito became the first (and the only successful) socialist leader to defy Stalin's leadership in the COMINFORM. This rift with the Soviet Union brought Tito much international recognition, but also triggered a period of instability often referred to as the Informbiro period. Tito's form of communism was labeled "Titoism" by Moscow, which encouraged purges against suspected "Titoites'" throughout the Eastern bloc.[citation needed]

Tito and Nikita Khrushchev in Skopje after the 1963 earthquake

On 26 June 1950, the National Assembly supported a crucial bill written by Milovan Đilas and Tito regarding "self-management" (samoupravljanje), a type of cooperative independent socialist experiment that introduced profit sharing and workplace democracy in previously state-run enterprises, which then became the direct social ownership of the employees. On 13 January 1953, they established that the law on self-management was the basis of the entire social order in Yugoslavia. Tito also succeeded Ivan Ribar as the President of Yugoslavia on 14 January 1953. After Stalin's death, Tito rejected the USSR's invitation for a visit to discuss normalization of relations between the two nations. Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin visited Tito in Belgrade in 1955 and apologized for wrongdoings by Stalin's administration. Tito visited the USSR in 1956, which signaled to the world that animosity between Yugoslavia and USSR was easing.[137] However, the relationship would reach another low in the late 1960s.[138]

The Tito-Stalin split had large ramifications for countries outside the USSR and Yugoslavia. It has, for example, been given as one of the reasons for the Slánský trial in Czechoslovakia, in which 14 high-level Communist officials were purged, with 11 of them being executed. Stalin put pressure on Czechoslovakia to conduct purges in order to discourage the spread of the idea of a "national path to socialism," which Tito espoused.[139]

Non-Alignment

Tito's diplomatic passport, 1973

U.S.-Yugoslav summit, 1978

Under Tito's leadership, Yugoslavia became a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement. In 1961, Tito co-founded the movement with Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, India's Jawaharlal Nehru, Indonesia's Sukarno and Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah, in an action called The Initiative of Five (Tito, Nehru, Nasser, Sukarno, Nkrumah), thus establishing strong ties with third world countries. This move did much to improve Yugoslavia's diplomatic position. On 1 September 1961, Josip Broz Tito became the first Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Tito's foreign policy led to relationships with a variety of governments, such as exchanging visits (1954 and 1956) with Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, where a street was named in his honor.

Tito was notable for pursuing a foreign policy of neutrality during the Cold War and for establishing close ties with developing countries. Tito's strong belief in self-determination caused the 1948 rift with Stalin and consequently, the Eastern Bloc. His public speeches often reiterated that policy of neutrality and cooperation with all countries would be natural as long as these countries did not use their influence to pressure Yugoslavia to take sides. Relations with the United States and Western European nations were generally cordial.

Yugoslavia had a liberal travel policy permitting foreigners to freely travel through the country and its citizens to travel worldwide,[140] whereas it was limited by most Communist countries. A number[quantify] of Yugoslav citizens worked throughout Western Europe. Tito met many world leaders during his rule, such as Soviet rulers Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev; Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, Indian politicians Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi; British Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, James Callaghan and Margaret Thatcher; U.S. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter; other political leaders, dignitaries and heads of state that Tito met at least once in his lifetime included Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Yasser Arafat, Willy Brandt, Helmut Schmidt, Georges Pompidou, Queen Elizabeth II, Hua Guofeng, Kim Il Sung, Sukarno, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Suharto, Idi Amin, Haile Selassie, Kenneth Kaunda, Gaddafi, Erich Honecker, Nicolae Ceaușescu, János Kádár and Urho Kekkonen. He also met numerous celebrities.

In 1953, Tito travelled to Britain for a state visit and met with Winston Churchill. He also toured Cambridge and visited the University Library.[141]

Tito visited India from 22 December 1954 through 8 January 1955.[142] After his return, he removed many restrictions on churches and spiritual institutions in Yugoslavia.

Tito also developed warm relations with Burma under U Nu, travelling to the country in 1955 and again in 1959, though he didn't receive the same treatment in 1959 from the new leader, Ne Win.

Because of its neutrality, Yugoslavia would often be rare among Communist countries to have diplomatic relations with right-wing, anti-Communist governments. For example, Yugoslavia was the only communist country allowed to have an embassy in Alfredo Stroessner's Paraguay.[143] One notable exception to Yugoslavia's neutral stance toward anti-communist countries was Chile under Pinochet; Yugoslavia was one of many countries which severed diplomatic relations with Chile after Salvador Allende was overthrown.[144] Yugoslavia also provided military aid and arms supplies to staunchly anti-Communist regimes such as that of Guatemala under Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García.[145]

Tito and Nasser in Aleppo in 1959

Tito and Nasser in Ljubljana in 1960

Tito and Willy Brandt in Bonn in 1970

Richard Nixon with Tito at the White House, 1971

Tito with Jimmy Carter in Washington in 1978

Reforms

Tito's calling card from 1967

On 7 April 1963, the country changed its official name to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Reforms encouraged private enterprise and greatly relaxed restrictions on religious expression.[140] Tito subsequently went on a tour of the Americas. In Chile, two government ministers resigned over his visit to that country.[146][147] In the autumn of 1960 Tito met President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the United Nations General Assembly meeting. Tito and Eisenhower discussed a range of issues from arms control to economic development. When Eisenhower remarked that Yugoslavia's neutralism was "neutral on his side", Tito replied that neutralism did not imply passivity but meant "not taking sides".[148]

In 1966 an agreement with the Vatican, fostered in part by the death in 1960 of anti-communist archbishop of Zagreb Aloysius Stepinac and shifts in the church's approach to resisting communism originating in the Second Vatican Council, accorded new freedom to the Yugoslav Roman Catholic Church, particularly to catechize and open seminaries. The agreement also eased tensions, which had prevented the naming of new bishops in Yugoslavia since 1945. Tito's new socialism met opposition from traditional communists culminating in conspiracy headed by Aleksandar Ranković.[149] In the same year Tito declared that Communists must henceforth chart Yugoslavia's course by the force of their arguments (implying an abandonment of Leninist orthodoxy and development of liberal Communism).[150] The State Security Administration (UDBA) saw its power scaled back and its staff reduced to 5000.

On 1 January 1967, Yugoslavia was the first communist country to open its borders to all foreign visitors and abolish visa requirements.[151] In the same year Tito became active in promoting a peaceful resolution of the Arab–Israeli conflict. His plan called for Arabs to recognize the state of Israel in exchange for territories Israel gained.[152]

In 1968, Tito offered Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubček to fly to Prague on three hours notice if Dubček needed help in facing down the Soviets.[153] In April 1969, Tito removed generals Ivan Gošnjak and Rade Hamović in the aftermath of the invasion of Czechoslovakia due to the unpreparedness of the Yugoslav army to respond to a similar invasion of Yugoslavia.[154]

In 1971, Tito was re-elected as President of Yugoslavia by the Federal Assembly for the sixth time. In his speech before the Federal Assembly he introduced 20 sweeping constitutional amendments that would provide an updated framework on which the country would be based. The amendments provided for a collective presidency, a 22-member body consisting of elected representatives from six republics and two autonomous provinces. The body would have a single chairman of the presidency and chairmanship would rotate among six republics. When the Federal Assembly fails to agree on legislation, the collective presidency would have the power to rule by decree. Amendments also provided for stronger cabinet with considerable power to initiate and pursue legislation independently from the Communist Party. Džemal Bijedić was chosen as the Premier. The new amendments aimed to decentralize the country by granting greater autonomy to republics and provinces. The federal government would retain authority only over foreign affairs, defense, internal security, monetary affairs, free trade within Yugoslavia, and development loans to poorer regions. Control of education, healthcare, and housing would be exercised entirely by the governments of the republics and the autonomous provinces.[155]

Tito's greatest strength, in the eyes of the western communists,[156] had been in suppressing nationalist insurrections and maintaining unity throughout the country. It was Tito's call for unity, and related methods, that held together the people of Yugoslavia.[157] This ability was put to a test several times during his reign, notably during the Croatian Spring (also referred as the Masovni pokret, maspok, meaning "Mass Movement") when the government suppressed both public demonstrations and dissenting opinions within the Communist Party. Despite this suppression, much of maspok's demands were later realized with the new constitution, heavily backed by Tito himself against opposition from the Serbian branch of the party.[citation needed] On 16 May 1974, the new Constitution was passed, and the aging Tito was named president for life, a status which he would enjoy for five years.

Tito's visits to the United States avoided most of the Northeast due to large minorities of Yugoslav emigrants bitter about communism in Yugoslavia.[158] Security for the state visits was usually high to keep him away from protesters, who would frequently burn the Yugoslav flag.[159] During a visit to the United Nations in the late 1970s emigrants shouted "Tito murderer" outside his New York hotel, for which he protested to United States authorities.[160]

Evaluation

Dominic McGoldrick writes that as the head of a "highly centralised and oppressive" regime, Tito wielded tremendous power in Yugoslavia, with his authoritarian rule administered through an elaborate bureaucracy which routinely suppressed human rights.[5] The main victims of this repression were during the first years known and alleged Stalinists, such as Dragoslav Mihailović and Dragoljub Mićunović, but during the following years even some of the most prominent among Tito's collaborators were arrested. On 19 November 1956 Milovan Đilas, perhaps the closest of Tito's collaborator and widely regarded as Tito's possible successor, was arrested because of his criticism against Tito's regime. The repression did not exclude intellectuals and writers, such as Venko Markovski who was arrested and sent to jail in January 1956 for writing poems considered anti-Titoist.

Even if after the reforms of 1961 Tito's presidency had become comparatively more liberal than other communist regimes, the Communist Party continued to alternate between liberalism and repression.[161] Yugoslavia managed to remain independent from the Soviet Union and its brand of socialism was in many ways the envy of Eastern Europe, but Tito's Yugoslavia remained a tightly controlled police state.[162] According to David Mates, outside the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia had more political prisoners than all of the rest of Eastern Europe combined.[163]

Tito's secret police was modelled on the Soviet KGB, its members were ever-present and often acted extrajudicially,[164] with victims including middle-class intellectuals, liberals and democrats.[165]

More generally, even if Yugoslavia had been signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, scant regard was paid to some of its provisions.[166]

Tito's Yugoslavia was based on respect for nationality, although Tito ruthlessly purged any flowerings of nationalism that threatened the Yugoslav federation.[167] However, the contrast between the deference given to some ethnic groups and the severe repression of others was sharp. Yugoslav law guaranteed nationalities to use their language, but for ethnic Albanians the assertion of ethnic identity was severely limited. Almost half of the political prisoners in Yugoslavia were ethnic Albanians imprisoned for asserting their ethnic identity.[168]

Yugoslavia's postwar development under Tito was significant but inferior to that of any European country adopting more market-based models and just similar to the economic development showed by countries adopting similar systems to that of Yugoslavia, such as Hungary or Bulgaria. From an economic perspective, the model implemented by Tito relied on debt and was not built on a stable foundation. By 1970 debt was not anymore contracted to finance investment, but to cover current expenses. The country ran into a deep economic crisis, marked by significant unemployment and inflation.[169] The sign that the robustness of the Yugoslav economy was an illusion appeared immediately after Tito’s death, when the country could not repay the massive debt accumulated between 1961 and 1980.[170] Between 1961 and 1980, external debt of Yugoslavia increased exponentially at the unsustainable pace of over 17% per year. The structure of the economy had formed in such a way that the future survival of the economy relied on the exclusive condition of future enlargement of the debt.

Declassified documents from the CIA state that already in 1967 it was clear that Tito's economic model had achieved growth of the gross national product at the cost of excessive and frequently unwise industrial investment and chronic deficit in the nation's balance of payment.[171]

When Tito died Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, the then President of Sinn Féin stated in An Phoblacht that "The death of President Tito deprives the world of a dedicated socialist and staunch internationalist..Tito instituted a federal democratic and socialist regime based on shared sovereignty and pioneered an economic and political system founded on workers' control and the principles of decentralised self-management...[He had an] enlightened and progressive internationalist policy of non-alignment and defiance of both major power blocs".[172]

Orson Welles once called him "the greatest man in the world today."[173]

Final years

After the constitutional changes of 1974, Tito began reducing his role in the day-to-day running of the state. He continued to travel abroad and receive foreign visitors, going to Beijing in 1977 and reconciling with a Chinese leadership that had once branded him a revisionist. In turn, Chairman Hua Guofeng visited Yugoslavia in 1979. In 1978, Tito travelled to the U.S. During the visit strict security was imposed in Washington, D.C. owing to protests by anti-communist Croat, Serb and Albanian groups.[174]

Tomb of Tito

Tito became increasingly ill over the course of 1979. During this time Vila Srna was built for his use near Morović in the event of his recovery.[175] On 7 January and again on 11 January 1980, Tito was admitted to the Medical Centre in Ljubljana, the capital city of the SR Slovenia, with circulation problems in his legs. His left leg was amputated soon afterward due to arterial blockages and he died of gangrene at the Medical Centre Ljubljana on 4 May 1980, three days short of his 88th birthday. His funeral drew many world statesmen.[176]

Based on the number of attending politicians and state delegations, at the time it was the largest state funeral in history; this concentration of dignitaries would be unmatched until the funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005 and the memorial service of Nelson Mandela in 2013.[177] Those who attended included four kings, 31 presidents, six princes, 22 prime ministers and 47 ministers of foreign affairs. They came from both sides of the Cold War, from 128 different countries out of 154 UN members at the time.[178]

Reporting on his death, The New York Times commented:

Tito sought to improve life. Unlike others who rose to power on the communist wave after WWII, Tito did not long demand that his people suffer for a distant vision of a better life. After an initial Soviet-influenced bleak period, Tito moved toward radical improvement of life in the country. Yugoslavia gradually became a bright spot amid the general grayness of Eastern Europe, The New York Times, 5 May 1980.[179]

Tito was interred in a mausoleum in Belgrade, which forms part of a memorial complex in the grounds of the Museum of Yugoslav History (formerly called "Museum 25 May" and "Museum of the Revolution"). The actual mausoleum is called House of Flowers (Kuća Cveća) and numerous people visit the place as a shrine to "better times". The museum keeps the gifts Tito received during his presidency. The collection also includes original prints of Los Caprichos by Francisco Goya, and many others.[180]

The Government of Serbia planned to merge it into the Museum of the History of Serbia.[181]

Legacy

Tito's statue in his birth village Kumrovec

"Long live Tito", graffiti in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2009

Marshal Tito Street at Skopje (26 July 1963, the Yugoslav People's Army support staff for earthquake)

During his life and especially in the first year after his death, several places were named after Tito. Several of these places have since returned to their original names, such as Podgorica, formerly Titograd (though Podgorica's international airport is still identified by the code TGD), and Užice, formerly known as Titovo Užice, which reverted to its original name in 1992. Streets in Belgrade, the capital, have all reverted to their original pre–World War II and pre-communist names as well. In 2004, Antun Augustinčić's statue of Broz in his birthplace of Kumrovec was decapitated in an explosion.[182] It was subsequently repaired. Twice in 2008, protests took place in what was then Zagreb's Marshal Tito Square (today the Republic of Croatia Square), organized by a group called Circle for the Square (Krug za Trg), with an aim to force the city government to rename it to its previous name, while a counter-protest by Citizens' Initiative Against Ustašism (Građanska inicijativa protiv ustaštva) accused the "Circle for the Square" of historical revisionism and neo-fascism.[183] Croatian president Stjepan Mesić criticized the demonstration to change the name.[184] In the Croatian coastal city of Opatija the main street (also its longest street) still bears the name of Marshal Tito, as do streets in numerous towns in Serbia, mostly in the country's north.[185] One of the main streets in downtown Sarajevo is called Marshal Tito Street, and Tito's statue in a park in front of the university campus (ex. JNA barrack "Maršal Tito") in Marijin Dvor is a place where Bosnians and Sarajevans still today commemorate and pay tribute to Tito (image on the right). The largest Tito monument in the world, about 10 m (33 ft) high, is located at Tito Square (Slovene: Titov trg), the central square in Velenje, Slovenia.[186][187] One of the main bridges in Slovenia's second largest city of Maribor is Tito Bridge (Titov most).[188] The central square in Koper, the largest Slovenian port city, is as well named Tito Square.[189] The main-belt asteroid 1550 Tito, discovered by Serbian astronomer Milorad B. Protić at Belgrade Observatory in 1937, was named in his honor.[190]

Every year a "Brotherhood and Unity" relay race is organized in Montenegro, Macedonia, and Serbia which ends at the "House of Flowers" in Belgrade on 25 May – the final resting place of Tito. At the same time, runners in Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina set off for Kumrovec, Tito's birthplace in northern Croatia. The relay is a left-over from the Relay of Youth from Yugoslav times, when young people made a similar yearly trek on foot through Yugoslavia that ended in Belgrade with a massive celebration.[191]

In 1992 TITO AND ME (Serbian: Тито и ја, Tito i ja), a 1992 Yugoslav comedy film by Serbian director Goran Marković, was released.

In the years following the dissolution of Yugoslavia, some historians stated that human rights were suppressed in Yugoslavia under Tito,[5][192] particularly in the first decade up until the Tito–Stalin Split. On 4 October 2011, the Slovenian Constitutional Court found a 2009 naming of a street in Ljubljana after Tito to be unconstitutional.[193] While several public areas in Slovenia (named during the Yugoslav period) do already bear Tito's name, on the issue of renaming an additional street the court ruled that:

The name "Tito" does not only symbolise the liberation of the territory of present-day Slovenia from fascist occupation in World War II, as claimed by the other party in the case, but also grave violations of human rights and basic freedoms, especially in the decade following World War II.[194]

The court, however, explicitly made it clear that the purpose of the review was "not a verdict on Tito as a figure or on his concrete actions, as well as not a historical weighing of facts and circumstances".[193] Slovenia has several streets and squares named after Tito, notably Tito Square in Velenje, incorporating a 10-meter statue.

Tito has also been named as responsible for systematic eradication of the ethnic German (Danube Swabian) population in Vojvodina by expulsions and mass executions following the collapse of the German occupation of Yugoslavia at the end of World War II, in contrast to his inclusive attitude towards other Yugoslav nationalities.[195]

Family and personal life

Tito carried on numerous affairs and was married several times. In 1918 he was brought to Omsk, Russia, as a prisoner of war. There he met Pelagija Belousova who was then fourteen; he married her a year later, and she moved with him to Yugoslavia. Pelagija bore him five children but only their son Žarko Leon[196] (born 4 February,[196] 1924) survived.[197] When Tito was jailed in 1928, she returned to Russia. After the divorce in 1936 she later remarried.

In 1936, when Tito stayed at the Hotel Lux in Moscow, he met the Austrian Lucia Bauer. They married in October 1936, but the records of this marriage were later erased.[198]

His next relationship was with Herta Haas, whom he married in 1940.[199] Broz left for Belgrade after the April War, leaving Haas pregnant. In May 1941, she gave birth to their son, Aleksandar "Mišo" Broz. All throughout his relationship with Haas, Tito had maintained a promiscuous life and had a parallel relationship with Davorjanka Paunović, who, under the codename "Zdenka", served as a courier in the resistance and subsequently became his personal secretary. Haas and Tito suddenly parted company in 1943 in Jajce during the second meeting of AVNOJ after she reportedly walked in on him and Davorjanka.[200] The last time Haas saw Broz was in 1946.[201] Davorjanka died of tuberculosis in 1946 and Tito insisted that she be buried in the backyard of the Beli Dvor, his Belgrade residence.[202]

Jovanka Broz and Tito in Postojna, 1960

His best known wife was Jovanka Broz. Tito was just shy of his 59th birthday, while she was 27, when they finally married in April 1952, with state security chief Aleksandar Ranković as the best man. Their eventual marriage came about somewhat unexpectedly since Tito actually rejected her some years earlier when his confidante Ivan Krajacic brought her in originally. At that time, she was in her early 20s and Tito, objecting to her energetic personality, opted for the more mature opera singer Zinka Kunc instead. Not one to be discouraged easily, Jovanka continued working at Beli Dvor, where she managed the staff and eventually got another chance after Tito's strange relationship with Zinka failed. Their relationship was not a happy one, however. It had gone through many, often public, ups and downs with episodes of infidelities and even allegations of preparation for a coup d'état by the latter pair. Certain unofficial reports suggest Tito and Jovanka even formally divorced in the late 1970s, shortly before his death. However, during Tito's funeral she was officially present as his wife, and later claimed rights for inheritance. The couple did not have any children.

Tito's grandchildren include Saša Broz, a theatre director in Croatia; Svetlana Broz, a cardiologist and writer in Bosnia-Herzegovina; and Josip Broz – Joška, Edvard Broz and Natali Klasevski, an artisan of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

As the President, Tito had access to extensive (state-owned) property associated with the office, and maintained a lavish lifestyle. In Belgrade he resided in the official residence, the Beli dvor, and maintained a separate private home. The Brijuni islands were the site of the State Summer Residence from 1949 on. The pavilion was designed by Jože Plečnik, and included a zoo. Close to 100 foreign heads of state were to visit Tito at the island residence, along with film stars such as Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Sophia Loren, Carlo Ponti, and Gina Lollobrigida.

Another residence was maintained at Lake Bled, while the grounds at Karađorđevo were the site of "diplomatic hunts". By 1974 the Yugoslav President had at his disposal 32 official residences, larger and small,[203] the yacht Galeb ("seagull"), a Boeing 727 as the presidential airplane, and the Blue Train.[204] After Tito's death the presidential Boeing 727 was sold to Aviogenex, the Galeb remained docked in Montenegro, while the Blue Train was stored in a Serbian train shed for over two decades.[205][206] While Tito was the person who held the office of president for by far the longest period, the associated property was not private and much of it continues to be in use by Yugoslav successor states, as public property, or maintained at the disposal of high-ranking officials.

As regards knowledge of languages, Tito replied that he spoke Serbo-Croatian, German, Russian, and some English.[207] Broz's official biographer and then fellow Central Committee-member Vladimir Dedijer stated in 1953 that he spoke "Serbo-Croatian ... Russian, Czech, Slovenian ... German (with a Viennese accent) ... understands and reads French and Italian ... [and] also speaks Kirghiz."[208]

In his youth Tito attended Catholic Sunday school, and was later an altar boy. After an incident where he was slapped and shouted at by a priest when he had difficulty assisting the priest to remove his vestments, Tito would not enter a church again. As an adult, he identified as an atheist.[209]

Every federal unit had a town or city with historic significance from the World War II period renamed to have Tito's name included. The largest of these was Titograd, now Podgorica, the capital city of Montenegro. With the exception of Titograd, the cities were renamed simply by the addition of the adjective "Tito's" ("Titov"). The cities were:

| Republic | City | Original name | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Titov Drvar | Drvar | |||

Titova Korenica | Korenica | |||

Titov Veles | Veles | |||

Titograda | Podgoricaa | |||

| Titovo Užice

| Užice

| ||

Titovo Velenje | Velenje | |||

athe capital of Montenegro. | ||||

Language and identity dispute

In the years after Tito's death up to the present, there has been some debate as to his identity. Tito's personal doctor, Aleksandar Matunović, wrote a book[210] about Tito in which he questioned his true origin, noting that Tito's habits and lifestyle could only mean that he was from an aristocratic family.[211] Serbian journalist Vladan Dinić, in Tito is not Tito, included several possible alternate identities of Tito, arguing that three separate people had identified as Tito.[212]

In 2013, a lot of media coverage was given to a declassified NSA study in Cryptologic Spectrum that concluded Tito had not spoken the Serbo-Croatian language as a native. The report noted that his speech had features of other Slavic languages (Russian and Polish). The hypothesis that "a non-Yugoslav, perhaps a Russian or a Pole" assumed Tito's identity was included with a note that this had happened during or before the Second World War.[213] The report notes Draža Mihailović's impressions of Tito's Russian origins after he had personally spoken with Tito.

However, the NSA's report was completely invalidated by Croatian experts. The report failed to recognize that Tito was a native speaker of the very distinctive local Kajkavian dialect of Zagorje. His acute accent, present only in Croatian dialects, and which Tito was able to pronounce perfectly, is the strongest evidence for his Zagorje origins.[214]

Origin of the name "Tito"

As the Communist Party was outlawed in Yugoslavia starting on 30 December 1920, Josip Broz took on many assumed names during his activity within the Party, including "Rudi", "Walter", and "Tito."[215] Broz himself explains: