Harold Wilson

The Right Honourable The Lord Wilson of Rievaulx KG OBE PC FRS FSS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

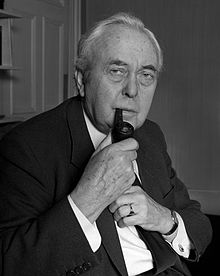

Wilson in 1986 by Allan Warren | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In office 4 March 1974 – 5 April 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | James Callaghan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In office 16 October 1964 – 19 June 1970 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Alec Douglas-Home | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In office 19 June 1970 – 4 March 1974 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In office 14 February 1963 – 16 October 1964 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | George Brown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Alec Douglas-Home | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Labour Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In office 14 February 1963 – 5 April 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hugh Gaitskell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | James Callaghan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | James Harold Wilson (1916-03-11)11 March 1916 Huddersfield, Yorkshire, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 May 1995(1995-05-24) (aged 79) London, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Colon cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | St. Mary's Old Church | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Labour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Mary Baldwin (m. 1940) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2, including Robin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, PC, FRS, FSS (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British Labour politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1964 to 1970 and 1974 to 1976.

Entering Parliament in 1945, Wilson was appointed a parliamentary secretary in the Attlee ministry and rose quickly through the ministerial ranks; he became Secretary for Overseas Trade in 1947 and was elevated to Cabinet shortly thereafter as President of the Board of Trade. In opposition to the next Conservative government, he served as Shadow Chancellor (1955–1961) and Shadow Foreign Secretary (1961–1963). Hugh Gaitskell, then Labour leader, died suddenly in 1963 and Wilson was elected leader. Narrowly winning the 1964 general election, Wilson won an increased majority in a snap 1966 election.

Wilson's first period as Prime Minister coincided with a period of low unemployment and relative economic prosperity, though hindered by significant problems with Britain's external balance of payments. In 1969 he sent British troops to Northern Ireland. After losing the 1970 election to Edward Heath, he spent four years as Leader of the Opposition before the February 1974 election resulted in a hung parliament. After Heath's talks with the Liberals broke down, Wilson returned to power as leader of a minority government until another general election in October, resulting in a narrow Labour victory. A period of economic crisis had begun to hit most Western countries, and in 1976 Wilson suddenly announced his resignation as Prime Minister.

Wilson's approach to socialism was moderate compared to others in his party at the time, emphasising programmes aimed at increasing opportunity in society, rather than on the controversial socialist goal of promoting wider public ownership of industry; he took little action to pursue the Labour constitution's stated dedication to nationalisation, though he did not formally disown it. Himself a member of the party's soft left, Wilson joked about leading a cabinet made up mostly of social democrats, comparing himself to a Bolshevik revolutionary presiding over a Tsarist cabinet, but there was arguably little to divide him ideologically from the cabinet majority.[1][2]

Overall, Wilson is seen to have managed a number of difficult political issues with considerable tactical skill, including such potentially divisive issues for his party as the role of public ownership, membership of the European Community, and the Vietnam War; he refused to allow British troops to take part, while continuing to maintain a costly military presence east of Suez.[3] His stated ambition of substantially improving Britain's long-term economic performance was left largely unfulfilled. He lost his energy and drive in his second premiership, and accomplished little as the leadership split over Europe and trade union issues began tearing Labour apart.[4]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 Early life

1.1 Education

1.2 Marriage

1.3 War service

2 Member of Parliament (1945–64)

2.1 Cabinet Minister, 1947–51

2.2 Shadow Cabinet, 1954–63

2.3 Opposition Leader, 1963–64

3 First period as Prime Minister (1964–70)

3.1 Domestic affairs

3.1.1 Economic policies

3.1.2 Social issues

3.1.3 Education

3.1.4 Housing

3.1.5 Social Services and welfare

3.1.6 Agriculture

3.1.7 Health

3.1.8 Workers

3.1.9 Transport

3.1.10 Regional development

3.1.11 Urban renewal

3.1.12 International development

3.1.13 Taxation

3.1.14 Liberal reforms

3.1.15 Record on income distribution

3.2 External affairs

3.2.1 United States

3.2.2 Europe

3.2.3 Asia

3.2.4 Africa

4 Defeat and return to opposition, 1970–74

5 Second period as Prime Minister (1974–76)

5.1 Domestic affairs

5.2 Northern Ireland

5.3 Resignation

6 Retirement and death, 1983–95

7 Political style

7.1 Reputation

8 Possible plots and conspiracy theories

9 Honours

9.1 Statues and other tributes

10 Scholastic honours

11 Cultural depictions

12 Arms

13 Ancestry

14 See also

15 References

16 Further reading

16.1 Bibliography

16.2 Biographical

16.3 Domestic policy and politics

16.4 Foreign policy

16.5 Historiography

17 External links

Early life

Wilson was born at 4 Warneford Road, Huddersfield, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England, on 11 March 1916. He came from a political family: his father James Herbert Wilson (1882–1971) was a works chemist who had been active in the Liberal Party and then joined the Labour Party. His mother Ethel (née Seddon; 1882–1957) was a schoolteacher before her marriage; in 1901 her brother Harold Seddon settled in Western Australia and became a local political leader. When Wilson was eight, he visited London and a much-reproduced photograph was taken of him standing on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street. At the age of ten he went with his family to Australia, where he became fascinated with the pomp and glamour of politics. On the way home he told his mother, "I am going to be Prime Minister."[5]

Education

Wilson won a scholarship to attend Royds Hall Grammar School, his local grammar school (now a comprehensive school) in Huddersfield in Yorkshire. His father, working as an industrial chemist, was made redundant in December 1930, and it took him nearly two years to find work; he moved to Spital in Cheshire, on the Wirral, in order to do so. Wilson was educated in the Sixth Form at the Wirral Grammar School for Boys, where he became Head Boy.

Garter banner of Harold Wilson at Jesus College Chapel, Oxford, where he studied Modern History

Wilson did well at school and, although he missed getting a scholarship, he obtained an exhibition; this, when topped up by a county grant, enabled him to study Modern History at Jesus College, Oxford, from 1934. At Oxford, Wilson was moderately active in politics as a member of the Liberal Party but was strongly influenced by G. D. H. Cole. His politics tutor, R. B. McCallum, considered Wilson as the best student he ever had.[6] He graduated in PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics) with "an outstanding first class Bachelor of Arts degree, with alphas on every paper" in the final examinations, and a series of major academic awards.[7] Biographer Roy Jenkins wrote:

Academically his results put him among prime ministers in the category of Peel, Gladstone, Asquith, and no one else. But...he lacked originality. What he was superb at was the quick assimilation of knowledge, combined with an ability to keep it ordered in his mind and to present it lucidly in a form welcome to his examiners.[8]

He continued in academia, becoming one of the youngest Oxford dons of the century at the age of 21. He was a lecturer in Economic History at New College from 1937, and a research fellow at University College.

Marriage

On New Year's Day 1940, in the chapel of Mansfield College, Oxford, he married Mary Baldwin who remained his wife until his death. Mary Wilson became a published poet. They had two sons, Robin and Giles (named after Giles Alington); Robin became a professor of Mathematics, and Giles became a teacher. In their twenties, his sons were under a kidnap threat from the IRA because of their father's prominence.[9]

War service

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Wilson volunteered for military service but was classed as a specialist and moved into the civil service instead. For much of this time, he was a research assistant to William Beveridge, the Master of University College, working on the issues of unemployment and the trade cycle. Wilson later became a statistician and economist for the coal industry. He was Director of Economics and Statistics at the Ministry of Fuel and Power in 1943–44, and received an OBE for his services.[10]

He was to remain passionately interested in statistics, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society in 1943.[11] As President of the Board of Trade, he was the driving force behind the Statistics of Trade Act 1947, which is still the authority governing most economic statistics in Great Britain. He was instrumental as Prime Minister in appointing Claus Moser as head of the Central Statistical Office, and was president of the Royal Statistical Society in 1972–73.

Member of Parliament (1945–64)

As the war drew to an end, he searched for a seat to fight at the impending general election. He was selected for the constituency of Ormskirk, then held by Stephen King-Hall. Wilson agreed to be adopted as the candidate immediately rather than delay until the election was called, and was therefore compelled to resign from his position in the Civil Service. He served as Praelector in Economics at University College between his resignation and his election to the House of Commons. He also used this time to write A New Deal for Coal, which used his wartime experience to argue for nationalisation of the coal mines on the grounds of the improved efficiency he predicted would ensue.

In the 1945 general election, Wilson won his seat in the Labour landslide. To his surprise, he was immediately appointed to the government by Prime Minister Clement Attlee as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Works. Two years later, he became Secretary for Overseas Trade, in which capacity he made several official trips to the Soviet Union to negotiate supply contracts.

The boundaries of his Ormskirk constituency was significantly altered before the general election of 1950. He stood instead for the new seat of Huyton near Liverpool, and was narrowly elected; he served there for 33 years until 1983.[12]

Cabinet Minister, 1947–51

Wilson was appointed President of the Board of Trade on 29 September 1947, becoming, at the age of 31, the youngest member of a British Cabinet in the 20th century. He took a lead in abolishing some wartime rationing, which he referred to as a "bonfire of controls".[13]

In mid-1949, with Chancellor of the Exchequer Stafford Cripps having gone to Switzerland in an attempt to recover his health, Wilson was one of a group of three young ministers, all of them former economics dons and wartime civil servants, convened to advise Prime Minister Attlee on financial matters. The others were Douglas Jay (Economic Secretary to the Treasury) and Hugh Gaitskell (Minister of Fuel and Power), both of whom soon grew to distrust him. Jay wrote of Wilson's role in the debates over whether or not to devalue sterling that “he changed sides three times within eight days and finished up facing both ways”. Wilson was given the task during his Swiss holiday of taking a letter to Cripps informing him of the decision to devalue, to which Cripps had been opposed.[14] Wilson had tarnished his reputation in both political and official circles.[13] Although a successful minister, he was regarded as self-important. He was not seriously considered for the job of Chancellor when Cripps stepped down in October 1950—it was given to Gaitskell—possibly in part because of his dubious role during devaluation.[15]

Wilson was becoming known in the Labour Party as a left-winger, and joined Aneurin Bevan and John Freeman in resigning from the government in April 1951 in protest at the introduction of National Health Service (NHS) medical charges to meet the financial demands imposed by the Korean War. At this time, Wilson was not yet regarded as a heavyweight politician: Hugh Dalton referred to him scornfully as "Nye [Bevan]’s dog".[16]

After Labour lost the 1951 election, he became the Chairman of Keep Left, Bevan's political group. At the bitter Morecambe Conference in late 1952, Wilson was one of the Bevanites elected as constituency representatives to Labour's National Executive Committee (NEC), whilst senior right-wingers such as Dalton and Herbert Morrison were voted off.[17]

Shadow Cabinet, 1954–63

Wilson had never made much secret that his support of the left-wing Aneurin Bevan was opportunistic. In early 1954, Bevan resigned from the Shadow Cabinet (elected by Labour MPs when the party was in opposition) over Labour's support for the setting-up of the South East Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO). Wilson, who had been runner-up in the elections, stepped up to fill the vacant place. He was supported in this by Richard Crossman, but his actions angered Bevan and the other Bevanites.[18]

Wilson's course in intra-party matters in the 1950s and early 1960s left him neither fully accepted nor trusted by the left or the right in the Labour Party. Despite his earlier association with Bevan, in 1955 he backed Hugh Gaitskell, the right-wing candidate in internal Labour Party terms, against Bevan for the party leadership.[19] Gaitskell appointed him Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1955, and he proved to be very effective.[20] One of his procedural moves caused a substantial delay to the progress of the Government's Finance Bill in 1955, and his speeches as Shadow Chancellor from 1956 were widely praised for their clarity and wit. He coined the term "Gnomes of Zurich" to ridicule Swiss bankers for selling Britain short and pushing the pound down by speculation.[21] He conducted an inquiry into the Labour Party's organisation following its defeat in the 1955 general election, which compared Labour's organisation to an antiquated "penny farthing" bicycle, and made various recommendations for improvements.[22] Unusually, Wilson combined the job of Chairman of the House of Commons' Public Accounts Committee with that of Shadow Chancellor from 1959, holding that position until 1963.

Gaitskell's leadership was weakened after the Labour Party's 1959 defeat, his controversial attempt to ditch Labour's commitment to nationalisation by scrapping Clause Four, and his defeat at the 1960 Party Conference over a motion supporting unilateral nuclear disarmament. Bevan had died in July 1960, so Wilson established himself as a leader of the Labour left by launching an opportunistic but unsuccessful challenge to Gaitskell's leadership in November 1960. Wilson would later be moved to the position of Shadow Foreign Secretary in 1961, before he challenged for the deputy leadership in 1962 but was defeated by George Brown.

Opposition Leader, 1963–64

Gaitskell died in January 1963, just as the Labour Party had begun to unite and appeared to have a very good chance of winning the next election, with the Macmillan Government running into trouble. Wilson was adopted as the left-wing candidate for the leadership, defeating Brown and James Callaghan to become the Leader of the Labour Party and the Leader of the Opposition.

At the Labour Party's 1963 Annual Conference, Wilson made both his best-remembered speech, on the implications of scientific and technological change. He argued that "the Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated measures on either side of industry". This speech did much to set Wilson's reputation as a technocrat not tied to the prevailing class system.[23]

Labour's 1964 election campaign was aided by the Profumo Affair, a ministerial sex scandal that had mortally wounded Harold Macmillan and hurt the Conservatives. Wilson made capital without getting involved in the less salubrious aspects. (Asked for a statement on the scandal, he reportedly said "No comment ... in glorious Technicolor!").[24]Sir Alec Douglas-Home was an aristocrat who had given up his peerage to sit in the House of Commons and become Prime Minister upon Macmillan's resignation. To Wilson's comment that he was out of touch with ordinary people since he was the 14th Earl of Home, Home retorted, "I suppose Mr. Wilson is the fourteenth Mr. Wilson".[25]

Wilson in 1964

First period as Prime Minister (1964–70)

Labour won the 1964 general election with a narrow majority of four seats, and Wilson became Prime Minister, the youngest person to hold that office since Lord Rosebery 70 years earlier. During 1965, by-election losses reduced the government's majority to a single seat; but in March 1966 Wilson took the gamble of calling another general election. The gamble paid off, because this time Labour achieved a 96-seat majority[26] over the Conservatives, who the previous year had made Edward Heath their leader.

Domestic affairs

Economic policies

In economic terms, Wilson's first three years in office were dominated by an ultimately doomed effort to stave off the devaluation of the pound. He inherited an unusually large external deficit on the balance of trade. This partly reflected the preceding government's expansive fiscal policy in the run-up to the 1964 election, and the incoming Wilson team tightened the fiscal stance in response. Many British economists advocated devaluation, but Wilson resisted, reportedly in part out of concern that Labour, which had previously devalued sterling in 1949, would become tagged as "the party of devaluation".[27] In the latter half of 1967, an attempt was made to prevent the recession in activity from going too far in the form of a stimulus to consumer durable spending through an easing of credit, which in turn prevented a rise in unemployment.[28]

After a costly battle, market pressures forced the government into devaluation in 1967. Wilson was much criticised for a broadcast in which he assured listeners that the "pound in your pocket" had not lost its value. It was widely forgotten that his next sentence had been "prices will rise". Economic performance did show some improvement after the devaluation, as economists had predicted. The devaluation, with accompanying austerity measures, successfully restored the balance of payments to surplus by 1969. This unexpectedly turned into a small deficit again in 1970. The bad figures were announced just before polling in the 1970 general election, and are often cited as one of the reasons for Labour's defeat.[27]

A main theme of Wilson's economic approach was to place enhanced emphasis on "indicative economic planning". He created a new Department of Economic Affairs to generate ambitious targets that were in themselves supposed to help stimulate investment and growth (the government also created a Ministry of Technology (shortened to Mintech) to support the modernisation of industry). The DEA itself was in part intended to serve as an expansionary counter-weight to what Labour saw as the conservative influence of the Treasury, though the appointment of Wilson's deputy, George Brown, as the Minister in charge of the DEA was something of a two-edged sword, in view of Brown's reputation for erratic conduct; in any case the government's decision over its first three years to defend sterling's parity with traditional deflationary measures ran counter to hopes for an expansionist push for growth. Though now out of fashion, the faith in indicative planning as a pathway to growth,[29] embodied in the DEA and Mintech, was at the time by no means confined to the Labour Party – Wilson built on foundations that had been laid by his Conservative predecessors, in the shape, for example, of the National Economic Development Council (known as "Neddy") and its regional counterparts (the "little Neddies").[27] Government intervention in industry was greatly enhanced, with the National Economic Development Office greatly strengthened, with the number of "little Neddies" was increased, from eight in 1964 to twenty-one in 1970. The government's policy of selective economic intervention was later characterised by the establishment of a new super-ministry of technology, under Tony Benn.[30]

The continued relevance of industrial nationalisation (a centrepiece of the post-War Labour government's programme) had been a key point of contention in Labour's internal struggles of the 1950s and early 1960s. Wilson's predecessor as leader, Hugh Gaitskell, had tried in 1960 to tackle the controversy head-on, with a proposal to expunge Clause Four (the public ownership clause) from the party's constitution, but had been forced to climb down. Wilson took a characteristically more subtle approach. He placated the party's left wing by renationalising the steel industry; otherwise, he left Clause Four formally in the constitution but in practice on the shelf.[27]

Wilson made periodic attempts to mitigate inflation, largely through wage-price controls—better known in Britain as "prices and incomes policy".[27] (As with indicative planning, such controls—though now generally out of favour—were widely adopted at that time by governments of different ideological complexions, including the Nixon administration in the United States.) Partly as a result of this reliance, the government tended to find itself repeatedly injected into major industrial disputes, with late-night "beer and sandwiches at Number Ten" an almost routine culmination to such episodes. Among the most damaging of the numerous strikes during Wilson's periods in office was a six-week stoppage by the National Union of Seamen, beginning shortly after Wilson's re-election in 1966, and conducted, he claimed, by "politically motivated men".

With public frustration over strikes mounting, Wilson's government in 1969 proposed a series of changes to the legal basis for industrial relations (labour law), which were outlined in a White Paper "In Place of Strife" put forward by the Employment Secretary Barbara Castle. Following a confrontation with the Trades Union Congress, which strongly opposed the proposals, and internal dissent from Home Secretary James Callaghan, the government substantially backed-down from its intentions. The Heath government (1970–1974) introduced the Industrial Relations Act 1971 with many of the same ideas, but this was largely repealed by the post-1974 Labour government. Some elements of these changes were subsequently to be enacted (in modified form) during the premiership of Margaret Thatcher.[27]

Wilson's government made a variety of changes to the tax system. Largely under the influence of the Hungarian-born economists Nicholas Kaldor and Thomas Balogh, an idiosyncratic Selective Employment Tax (SET) was introduced that was designed to tax employment in the service sectors while subsidising employment in manufacturing. (The rationale proposed by its economist authors derived largely from claims about potential economies of scale and technological progress, but Wilson in his memoirs stressed the tax's revenue-raising potential.) The SET did not long survive the return of a Conservative government. Of longer-term significance, Capital Gains Tax (CGT) was introduced across the UK on 6 April 1965.[31] Across his two periods in office, Wilson presided over significant increases in the overall tax burden in the UK. In 1974, three weeks after forming a new government, Wilson's new chancellor Denis Healey partially reversed the 1971 reduction in the top rate of tax from 90% to 75%, increasing it to 83% in his first budget, which came into law in April 1974. This applied to incomes over £20,000 (equivalent to £204,729 in 2018),[32], and combined with a 15% surcharge on 'un-earned' income (investments and dividends) could add to a 98% marginal rate of personal income tax. In 1974, as many as 750,000 people were liable to pay the top-rate of income tax.[33] Labour's identification with high tax rates was to prove one of the issues that helped the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher and John Major dominate British politics during the 1980s and early-to-mid-1990s.

Wilson had entered power at a time when unemployment stood at around 400,000. It still stood 371,000 by early 1966 after a steady fall during 1965, but by March 1967 it stood at 631,000. It fell again towards the end of the decade, standing at 582,000 by the time of the general election in June 1970.[34]

Social issues

A number of liberalising social reforms were passed through parliament during Wilson's first period in government. These dealt with the death penalty, homosexual acts, abortion, censorship and the voting age. There were new restrictions on immigration. Wilson personally, coming culturally from a provincial non-conformist background, showed no particular enthusiasm for much of this agenda.[35]

Education

Education held special significance for a socialist of Wilson's generation, in view of its role in both opening up opportunities for children from working-class backgrounds and enabling Britain to seize the potential benefits of scientific advances. Under the first Wilson government, for the first time in British history, more money was allocated to education than to defence.[36] Wilson continued the rapid creation of new universities, in line with the recommendations of the Robbins Report, a bipartisan policy already in train when Labour took power.

Wilson promoted the concept of an Open University, to give adults who had missed out on tertiary education a second chance through part-time study and distance learning. His political commitment included assigning implementation responsibility to Baroness Lee, the widow of Aneurin Bevan.[37] By 1981, 45,000 students had received degrees through the Open University.[37] Money was also channelled into local-authority run colleges of education.[30]

Wilson's record on secondary education is, by contrast, highly controversial. Pressure grew for the abolition of the selective principle underlying the "eleven-plus", and replacement with Comprehensive schools which would serve the full range of children (see the article Debates on the grammar school). Comprehensive education became Labour Party policy. From 1966 to 1970, the proportion of children in comprehensive schools increased from about 10% to over 30%.[38]

Labour pressed local authorities to convert grammar schools into comprehensives. Conversion continued on a large scale during the subsequent Conservative Heath administration, although the Secretary of State, Margaret Thatcher, ended the compulsion of local governments to convert.

A major controversy that arose during Wilson's first government was the decision that the government could not fulfil its long-held promise to raise the school leaving age to 16, because of the investment required in infrastructure, such as extra classrooms and teachers.

Overall, public expenditure on education rose as a proportion of GNP from 4.8% in 1964 to 5.9% in 1968, and the number of teachers in training increased by more than a third between 1964 and 1967.[39] The percentage of students staying on at school after the age of sixteen increased similarly, and the student population increased by over 10% each year. Pupil-teacher ratios were also steadily reduced. As a result of the first Wilson government's educational policies, opportunities for working-class children were improved, while overall access to education in 1970 was broader than in 1964.[40] As summarised by Brian Lapping,

"The years 1964–70 were largely taken up with creating extra places in universities, polytechnics, technical colleges, colleges of education: preparing for the day when a new Act would make it the right of a student, on leaving school, to have a place in an institution of further education."[30]

In 1966, Wilson was created the first Chancellor of the newly created University of Bradford, a position he held until 1985.

Housing

Housing was a major policy area under the first Wilson government. During Wilson's time in office from 1964 to 1970, more new houses were built than in the last six years of the previous Conservative government. The proportion of council housing rose from 42% to 50% of the total,[41] while the number of council homes built increased steadily, from 119,000 in 1964 to 133,000 in 1965 and to 142,000 in 1966. Allowing for demolitions, 1.3 million new homes were built between 1965 and 1970,[37] To encourage home ownership, the government introduced the Option Mortgage Scheme (1968), which made low-income housebuyers eligible for subsidies (equivalent to tax relief on mortgage interest payments).[42] This scheme had the effect of reducing housing costs for buyers on low incomes[43] and enabling more people to become owner occupiers.[44] In addition, house owners were exempted from capital gains tax. Together with the Option Mortgage Scheme, this measure stimulated the private housing market.[45]

Significant emphasis was also placed on town planning, with new conservation areas introduced and a new generation of new towns built, notably Milton Keynes. The New Towns Acts of 1965 and 1968 together gave the government the authority (through its ministries) to designate any area of land as a site for a New Town.[46]

Social Services and welfare

Wilson on a visit to a retirement home in Washington, Tyne and Wear

According to A.B. Atkinson, social security received much more attention from the first Wilson government than it did during the previous thirteen years of Conservative government.[28] Following its victory in the 1964 general election, Wilson's government began to increase social benefits. Prescription charges for medicines were abolished immediately, while pensions were raised to a record 21% of average male industrial wages. In 1966, the system of National Assistance (a social assistance scheme for the poor) was overhauled and renamed Supplementary Benefit. The means test was replaced with a statement of income, and benefit rates for pensioners (the great majority of claimants) were increased, granting them a real gain in income. Before the 1966 election, the widow's pension was tripled. Due to austerity measures following an economic crisis, prescription charges were re-introduced in 1968 as an alternative to cutting the hospital building programme, although those sections of the population who were most in need (including supplementary benefit claimants, the long-term sick, children, and pensioners) were exempted from charges.[47]

The widow's earning rule was also abolished,[37] while a range of new social benefits was introduced. An Act was passed which replaced National Assistance with Supplementary Benefits. The new Act laid down that people who satisfied its conditions were entitled to these noncontributory benefits. Unlike the National Assistance scheme, which operated like state charity for the worst-off, the new Supplementary Benefits scheme was a right of every citizen who found himself or herself in severe difficulties. Those persons over the retirement age with no means who were considered to be unable to live on the basic pension (which provided less than what the government deemed as necessary for subsistence) became entitled to a "long term" allowance of an extra few shillings a week. Some simplification of the procedure for claiming benefits was also introduced.[30] From 1966, an exceptionally severe disablement allowance was added “for those claimants receiving constant attendance allowance which was paid to those with the higher or intermediate rates of constant attendance allowance and who were exceptionally severely disabled.”[48] Redundancy payments were introduced in 1965 to lessen the impact of unemployment, and earnings-related benefits for maternity,[49] unemployment, sickness, industrial injuries and widowhood were introduced in 1966, followed by the replacement of flat-rate family allowances with an earnings-related scheme in 1968.[50] From July 1966 onwards, the temporary allowance for widow of severely disabled pensioners was extended from 13 to 26 weeks.[51]

Increases were made in pensions and other benefits during Wilson's first year in office that were the largest ever real term increases carried out up until that point.[52] Social security benefits were markedly increased during Wilson's first two years in office, as characterised by a budget passed in the final quarter of 1964 which raised the standard benefit rates for old age, sickness and invalidity by 18.5%.[53] In 1965, the government increased the national assistance rate to a higher level relative to earnings, and via annual adjustments, broadly maintained the rate at between 19% and 20% of gross industrial earnings until the start of 1970.[28] In the five years from 1964 up until the last increases made by the First Wilson Government, pensions went up by 23% in real terms, supplementary benefits by 26% in real terms, and sickness and unemployment benefits by 153% in real terms (largely as a result of the introduction of earnings-related benefits in 1967).[54]

Agriculture

Under the First Wilson Government, subsidies for farmers were increased.[55][56] Farmers who wished to leave the land or retire became eligible for grants or annuities if their holdings were sold for approved amalgamations, and could receive those benefits whether they wished to remain in their farmhouses or not. A Small Farmers Scheme was also extended, and from 1 December 1965, 40,000 more farmers became eligible for the maximum £1,000 grant. New grants to agriculture also encouraged the voluntary pooling of smallholdings, and in cases where their land was purchased for non-commercial purposes, tenant-farmers could now receive double the previous "disturbance compensation."[57] A Hill Land Improvement Scheme, introduced by the Agriculture Act of 1967, provided 50% grants for a wide range of land improvements, along with a supplementary 10% grant on drainage works benefitting hill land.[58] The Agriculture Act 1967 also provided grants to promote farm amalgamation and to compensate outgoers.[59]

Health

The proportion of GNP spent on the NHS rose from 4.2% in 1964 to about 5% in 1969. This additional expenditure provided for an energetic revival of a policy of building health centres for GPs, extra pay for doctors who served in areas particularly short of them, a significant growth in hospital staffing, and a significant increase in a hospital building programme. Far more money was spent each year on the NHS than under the 1951–64 Conservative governments, while much more effort was put into modernising and reorganising the health service.[30] Stronger central and regional organisations were established for bulk purchase of hospital supplies, while some efforts were made to reduce inequalities in standards of care. In addition, the government increased the intake to medical schools.[28]

The 1966 Doctor's Charter introduced allowances for rent and ancillary staff, significantly increased the pay scales, and changed the structure of payments to reflect "both qualifications of doctors and the form of their practices, i.e. group practice." These changes not only led to higher morale, but also resulted in the increased use of ancillary staff and nursing attachments, a growth in the number of health centres and group practices, and a boost in the modernisation of practices in terms of equipment, appointment systems, and buildings.[46] The charter introduced a new system of payment for GPs, with refunds for surgery, rents, and rates, to ensure that the costs of improving his surgery did not diminish the doctor's income, together with allowances for the greater part of ancillary staff costs. In addition, a Royal Commission on medical education was set up, partly to draw up ideas for training GPs (since these doctors, the largest group of all doctors in the country, had previously not received any special training, "merely being those who, at the end of their pre-doctoral courses, did not go on for further training in any speciality).[30]

In 1967, local authorities were empowered to provide family planning advice to any who requested it and to provide supplies free of charge.[47] In addition, medical training was expanded following the Todd Report on medical education in 1968.[46][60] In addition, National Health expenditure rose from 4.2% of GNP in 1964 to 5% in 1969 and spending on hospital construction doubled.[41] The Health Services and Public Health Act 1968 empowered local authorities to maintain workshops for the elderly either directly or via the agency of a voluntary body. A Health Advisory Service was later established to investigate and confront the problems of long-term psychiatric and mentally subnormal hospitals in the wave of numerous scandals.[46] The Family Planning Act 1967 empowered local authorities to set up a family planning service with free advice and means-tested provision of contraceptive devices while the Clean Air Act 1968 extended powers to combat air pollution.[61] More money was also allocated to hospitals treating the mentally ill.[30] In addition, a Sports Council was set up to improve facilities.[62] Direct government expenditure on sports more than doubled from £0.9 million in 1964/65 to £2 million in 1967/68, while 11 regional Sports Councils had been set up by 1968. In Wales, five new health centres had been opened by 1968, whereas none had been opened from 1951 to 1964, while spending on health and welfare services in the region went up from £55.8 million in 1963/64 to £83.9 million in 1967/68.[57]

Workers

The Industrial Training Act 1964 set up an Industrial Training Board to encourage training for people in work,[61] and within 7 years there were “27 ITBs covering employers with some 15 million workers.”[63] From 1964 to 1968, the number of training places had doubled.[57] The Docks and Harbours Act (1966) and the Dock Labour Scheme (1967) reorganised the system of employment in the docks in order to put an end to casual employment.[41] The changes made to the Dock Labour Scheme in 1967 ensured a complete end to casual labour on the docks, effectively giving workers the security of jobs for life.[64] Trade unions also benefited from the passage of the Trade Dispute Act 1965. This restored the legal immunity of trade union officials, thus ensuring that they could no longer be sued for threatening to strike.[65]

The First Wilson Government also encouraged married women to return to teaching and improved Assistance Board Concessionary conditions for those teaching part-time, “by enabling them to qualify for pension rights and by formulating a uniform scale of payment throughout the country." Soon after coming into office, midwives and nurses were given an 11% pay increase,[57] and according to one MP, nurses also benefited from the largest pay rise they had received in a generation.[66] In May 1966, Wilson announced 30% pay rises for doctors and dentists – a move which did not prove popular with unions, as the national pay policy at the time was for rises of between 3% and 3.5%.[67]

Much needed improvements were made in junior hospital doctors' salaries. From 1959 to 1970, while the earnings of manual workers increased by 75%, the salaries of registrars more than doubled while those of house officers more than trebled. Most of these improvements, such as for nurses, came in the pay settlements of 1970. On a limited scale, reports by the National Board for Prices and Incomes encouraged incentive payments schemes to be development in local government and elsewhere. In February 1969, the government accepted an "above the ceiling" increase for farmworkers, a low-paid group. Some groups of professional workers, such as nurses, teachers, and doctors, gained substantial awards.[28]

Transport

The Travel Concessions Act of 1964, one of the first Acts passed by the First Wilson Government, provided concessions to all pensioners travelling on buses operated by municipal transport authorities.[68] The Transport Act 1968 established the principle of government grants for transport authorities if uneconomic passenger services were justified on social grounds. A National Freight Corporation was also established to provide integrated rail freight and road services. Public expenditure on roads steadily increased and stricter safety precautions were introduced, such as the breathalyser test for drunken driving,[36] under the 1967 Road Traffic Act.[30] The Transport Act gave a much needed financial boost to British Rail, treating them like they were a company which had become bankrupt but could now, under new management, carry on debt-free. The act also established a national freight corporation and introduced government rail subsidies for passenger transport on the same basis as existing subsidies for roads to enable local authorities to improve public transport in their areas.[30]

The road building programme was also expanded, with capital expenditure increased to 8% of GDP, "the highest level achieved by any post-war government".[69] Central government expenditure on roads went up from £125 million in 1963/64 to £225 million in 1967/68, while a number of road safety regulations were introduced, covering seat belts, lorry drivers’ hours, car and lorry standards, and an experimental 70 mile per hour speed limit. In Scotland, spending on trunk roads went up from £6.8 million in 1963/64 to £15.5 million in 1966/67, while in Wales, spending on Welsh roads went up from £21.2 million in 1963/64 to £31.4 million in 1966/67.[57]

Regional development

Encouragement of regional development was given increased attention under the First Wilson Government, with the aim of narrowing economic dispratiies between the various regions. A policy was introduced in 1965 whereby any new government organisation should be established outside London and in 1967 the government decided to give preference to development areas. A few government departments were also moved out of London, with the Royal Mint moved to South Wales, the Giro and Inland Revenue to Bootle, and the Motor Tax Office to Swansea.[70] A new Special Development Status was also introduced in 1967 to provide even higher levels of assistance.[37] In 1966, five development areas (covering half the population in the UK) were established, while subsidies were provided for employers recruiting new employees in the Development Areas.[27] A Highlands and Islands Development Board was also set up to “re-invigorate” the north of Scotland.[57]

The Industrial Development Act 1966 changed the name of Development Districts (parts of the country with higher levels of unemployment than the national average and which governments sought to encourage greater investment in) to Development Areas and increased the percentage of the workforce covered by development schemes from 15% to 20%, which mainly affected rural areas in Scotland and Wales. Tax allowances were replaced by grants in order to extend coverage to include firms which were not making a profit, and in 1967 a Regional Employment Premium was introduced. Whereas the existing schemes tended to favour capital-intensive projects, this aimed for the first time at increasing employment in depressed areas. Set at £1.50 a man per week and guaranteed for seven years, the Regional Employment Premium subsidised all manufacturing industry (though not services) in Development Areas.[37]

Regional unemployment differentials were narrowed, and spending on regional infrastructure was significantly increased. Between 1965–66 and 1969–70, yearly expenditure on new construction (including power stations, roads, schools, hospitals and housing) rose by 41% in the United Kingdom as a whole. Subsidies were also provided for various industries (such as shipbuilding in Clydeside), which helped to prevent a number of job losses. It is estimated that, between 1964 and 1970, 45,000 government jobs were created outside London, 21,000 of which were located in the Development Areas.[70] The Local Employment Act, passed in March 1970, embodied the government's proposals for assistance to 54 "intermediate" employment exchange areas not classified as full "development" areas.[71]

Funds allocated to regional assistance more than doubled, from £40 million in 1964/65 to £82 million in 1969/70, and from 1964 to 1970, the number of factories completed was 50% higher than from 1960 to 1964, which helped to reduce unemployment in development areas. In 1970, the unemployment rate in development areas was 1.67 times the national average, compared to 2.21 times in 1964. Although national rates of unemployment were higher in 1970 than in the early 1960s, unemployment rates in the development areas were lower and had not increased for three years.[37] Altogether, the impact of the first Wilson government's regional development policies was such that, according to one historian, the period 1963 to 1970 represented "the most prolonged, most intensive, and most successful attack ever launched on regional problems in Britain."[27]

Urban renewal

A number of subsidies were allocated to local authorities faced with acute areas of severe poverty (or other social problems).[30] The Housing Act 1969 provided local authorities with the duty of working out what to do about 'unsatisfactory areas'. Local authorities could declare 'general improvement areas' in which they would be able to buy up land and houses, and spend environmental improvement grants. On the same basis, taking geographical areas of need, a package was developed by the government which resembled a miniature poverty programme.[50] In July 1967, the government decided to pour money into what the Plowden Committee defined as Educational Priority Areas, poverty-stricken areas where children were environmentally deprived. A number of poor inner-city areas were subsequently granted EPA status (despite concerns that Local Education Authorities would be unable to finance Educational Priority Areas).[65] From 1968 to 1970, 150 new schools were built under the educational priority programme.[28]

International development

A new Ministry of Overseas Development was established, with its greatest success at the time being the introduction of interest-free loans for the poorest countries.[37] The Minister of Overseas Development, Barbara Castle, set a standard in interest relief on loans to developing nations which resulted in changes to the loan policies of many donor countries, "a significant shift in the conduct of rich white nations to poor brown ones." Loans were introduced to developing countries on terms that were more favourable to them than those given by governments of all other developed countries at that time. In addition, Castle was instrumental in setting up an Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex to devise ways of tackling global socio-economic inequalities. Overseas aid suffered from the austerity measures introduced by the first Wilson government in its last few years in office, with British aid as a percentage of GNP falling from 0.53% in 1964 to 0.39% in 1969.[30]

Taxation

Various changes were also made to the tax system which benefited workers on low and middle incomes. Married couples with low incomes benefited from the increases in the single personal allowance and marriage allowance. In 1965, the regressive allowance for national insurance contributions was abolished and the single personal allowance, marriage allowance and wife's earned income relief were increased. These allowances were further increased in the tax years 1969–70 and 1970–71. Increases in the age exemption and dependant relative's income limits benefited the low-income elderly.[28] In 1967, new tax concessions were introduced for widows.[72]

Increases were made in some of the minor allowances in the 1969 Finance Act, notably the additional personal allowance, the age exemption and age relief and the dependent relative limit. Apart from the age relief, further adjustments in these concessions were implemented in 1970.[28]

1968 saw the introduction of aggregation of the investment income of unmarried minors with the income of their parents. According to Michael Meacher, this change put an end to a previous inequity whereby two families, in otherwise identical circumstances, paid differing amounts of tax "simply because in one case the child possessed property transferred to it by a grandparent, while in the other case the grandparent's identical property was inherited by the parent."[28]

In the 1969 budget, income tax was abolished for about 1 million of the lowest paid and reduced for a further 600,000 people,[56] while in the government's last budget (introduced in 1970), two million small taxpayers were exempted from paying any income tax altogether.[73]

Liberal reforms

A wide range of liberal measures were introduced during Wilson's time in office. The Matrimonial Proceedings and Property Act 1970 made provision for the welfare of children whose parents were about to divorce or be judicially separated, with courts (for instance) granted wide powers to order financial provision for children in the form of maintenance payments made by either parent.[46] This legislation allowed courts to order provision for either spouse and recognised the contribution to the joint home made during marriage.[61] That same year, spouses were given an equal share of household assets following divorce via the Matrimonial Property Act. The Race Relations Act 1968 was also extended in 1968 and in 1970 the Equal Pay Act 1970 was passed.[47] Another important reform, the Welsh Language Act 1967, granted 'equal validity' to the declining Welsh language and encouraged its revival. Government expenditure was also increased on both sport and the arts.[41] The Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969, passed in response to the Aberfan tragedy, made provision for preventing disused tips from endangering members of the public.[74] In 1967, corporal punishment in borstals and prisons was abolished.[75] 7 regional associations were established to develop the arts, and government expenditure on cultural activities rose from £7.7 million in 1964/64 to £15.3 million in 1968/69. A Criminal Injuries Compensation Board was also set up, which had paid out over £2 million to victims of criminal violence by 1968.[57]

The Commons Registration Act 1965 provided for the registration of all common land and village greens, whilst under the Countryside Act 1968, local authorities could provide facilities "for enjoyment of such lands to which the public has access".[46] The Family Provision Act 1966 amended a series of pre-existing estate laws mainly related to persons who died interstate. The legislation increased the amount that could be paid to surviving spouses if a will had not been left, and also expanded upon the jurisdiction of county courts, which were given the jurisdiction of high courts under certain circumstances when handling matters of estate. The rights of adopted children were also improved with certain wording changed in the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act 1938 to bestow upon them the same rights as natural-born children. In 1968, the Nurseries and Child-Minders Regulation Act 1948 was updated to include more categories of childminders.[76] A year later, the Family Law Reform Act 1969 was passed, which allowed people born outside marriage to inherit on the intestacy of either parent.[77] In 1967, homosexuality was partially decriminalised by the passage of the Sexual Offences Act.[30] The Public Records Act 1967 also introduced a thirty-year rule for access to public records, replacing a previous fifty-year rule.[78]

Record on income distribution

Despite the economic difficulties faced by the first Wilson government, it succeeded in maintaining low levels of unemployment and inflation during its time in office. Unemployment was kept below 2.7%, and inflation for much of the 1960s remained below 4%. Living standards generally improved, while public spending on housing, social security, transport, research, education and health went up by an average of more than 6% between 1964 and 1970.[79] The average household grew steadily richer, with the number of cars in the United Kingdom rising from one to every 6.4 persons to one for every five persons in 1968, representing a net increase of three million cars on the road. The rise in the standard of living was also characterised by increased ownership of various consumer durables from 1964 to 1969, as demonstrated by television sets (from 88% to 90%), refrigerators (from 39% to 59%), and washing machines (from 54% to 64%).[30]

By 1970, income in Britain was more equally distributed than in 1964, mainly because of increases in cash benefits, including family allowances.[80]

According to one historian:[who?]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

In its commitment to social services and public welfare, the Wilson government put together a record unmatched by any subsequent administration, and the mid-sixties are justifiably seen as the 'golden age' of the welfare state.[79]

As noted by Ben Pimlott, the gap between those on lowest incomes and the rest of the population "had been significantly reduced" under Wilson's first government.[81] The first Wilson government thus saw the distribution of income became more equal,[40] while reductions in poverty took place.[82] These achievements were mainly brought about by several increases in social welfare benefits,[83] such as supplementary benefit, pensions and family allowances, the latter of which were doubled between 1964 and 1970 (although most of the increase in family allowances did not come about until 1968). A new system of rate rebates was introduced, which benefited one million households by the end of the 1960s.[37] Increases in national insurance benefits in 1965, 1967, 1968 and 1969 ensured that those dependant on state benefits saw their disposable incomes rise faster than manual wage earners, while income differentials between lower income and higher income workers were marginally narrowed. Greater progressivity was introduced in the tax system, with greater emphasis on direct (income-based) as opposed to indirect (typically expenditure-based) taxation as a means of raising revenue, with the amount raised by the former increasing twice as much as that of the latter.[84] Also, in spite of an increase in unemployment, the poor improved their share of the national income while that of the rich was slightly reduced.[2] Despite various cutbacks after 1966, expenditure on services such as education and health was still much higher as a proportion of national wealth than in 1964. In addition, by raising taxes to pay their reforms, the government paid careful attention to the principle of redistribution, with disposable incomes rising for the lowest paid while falling amongst the wealthiest during its time in office.[85]

Between 1964 and 1968, benefits in kind were significantly progressive, in that over the period those in the lower half of the income scale benefited more than those in the upper half. On average those receiving state benefits benefited more in terms of increases in real disposable income than the average manual worker or salaried employee between 1964 and 1969.[70] From 1964 to 1969, low-wage earners did substantially better than other sections of the population. In 1969, a married couple with two children were 11.5% per cent richer in real terms, while for a couple with three children, the corresponding increase was 14.5%, and for a family with four children, 16.5%.[86] From 1965 to 1968, the income of single pensioner households as a percentage of other one adult households rose from 48.9% to 52.5%. For two pensioner households, the equivalent increase was from 46.8% to 48.2%.[28] In addition, mainly as a result of big increases in cash benefits, unemployed persons and large families gained more in terms of real disposable income than the rest of the population during Wilson's time in office.[40]

As noted by Paul Whiteley, pensions, sickness, unemployment, and supplementary benefits went up more in real terms under the First Wilson Government than under the preceding Conservative administration:

“To compare the Conservative period of office with the Labour period, we can use the changes in benefits per year as a rough estimate of comparative performance. For the Conservatives and Labour respectively increases in supplementary benefits per year were 3.5 and 5.2 percentage points, for sickness and unemployment benefits 5.8 and 30.6 percentage points, for pensions 3.8 and 4.6, and for family allowances −1.2 and −2.6. Thus the poor, the retired, the sick and the unemployed did better in real terms under Labour than they did under Conservatives, and families did worse.”[54]

Between 1964 and 1968, cash benefits rose as a percentage of income for all households but more so for poorer than for wealthier households. As noted by the economist Michael Stewart,

"it seems indisputable that the high priority the Labour Government gave to expenditure on education and the health service had a favourable effect on income distribution."[70]

For a family with two children in the income range £676 to £816 per annum, cash benefits rose from 4% of income in 1964 to 22% in 1968, compared with a change from 1% to 2% for a similar family in the income range £2,122 to £2,566 over the same period. For benefits in kind the changes over the same period for similar families were from 21% to 29% for lower income families and from 9% to 10% for higher income families. When taking into account all benefits, taxes and Government expenditures on social services, the first Wilson government succeeded in bringing about a reduction in income inequality. As noted by the historian Kenneth O. Morgan,

"In the long term, therefore, fortified by increases in supplementary and other benefits under the Crossman regime in 1968–70, the welfare state had made some impact, almost by inadvertence, on social inequality and the maldistribution of real income".[87]

Public expenditure as a percentage of GDP rose significantly under the 1964–1970 Labour government, from 34% in 1964–65 to nearly 38% of GDP by 1969–70, whilst expenditure on social services rose from 16% of national income in 1964 to 23% by 1970.[37] These measures had a major impact on the living standards of low-income Britons, with disposable incomes rising faster for low-income groups than for high-income groups during the course of the 1960s. When measuring disposable income after taxation but including benefits, the total disposable income of those on the highest incomes fell by 33%, whilst the total disposable income of those on the lowest incomes rose by 104%.[37] As noted by one historian, "the net effect of Labour's financial policies was indeed to make the rich poorer and the poor richer".[88]

External affairs

United States

Wilson with President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House in 1966

Wilson believed in a strong "Special Relationship" with the United States and wanted to highlight his dealings with the White House to strengthen his own prestige as a statesman. President Lyndon Johnson disliked Wilson, and ignored any "special" relationship. Vietnam was a sore point.[89] Johnson needed and asked for help to maintain American prestige. Wilson offered lukewarm verbal support but no military aid. Wilson's policy angered the left-wing of his Labour Party.[90] Wilson and Johnson also differed sharply on British economic weakness and its declining status as a world power. Historian Jonathan Colman concludes it made for the most unsatisfactory "special" relationship in the 20th century.[91]

Europe

Wilson with West German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard in 1965

Among the more challenging political dilemmas Wilson faced was the issue of British membership of the European Community, the forerunner of the present European Union. An entry attempt was vetoed in 1963 by French President Charles de Gaulle. The Labour Party in Opposition had been divided on the issue, with Hugh Gaitskell having come out in 1962 in opposition to Britain joining the Community.[92] After initial hesitation, Wilson's Government in May 1967 lodged the UK's second application to join the European Community. It was vetoed by de Gaulle in November 1967.[93] After De Gaulle lost power, Conservative prime minister Edward Heath negotiated Britain's admission to the EC in 1973.

Wilson in opposition showed political ingenuity in devising a position that both sides of the party could agree on, opposing the terms negotiated by Heath but not membership in principle. Labour's 1974 manifesto included a pledge to renegotiate terms for Britain's membership and then hold a referendum on whether to stay in the EC on the new terms. This was a constitutional procedure without precedent in British history.

Following Wilson's return to power, the renegotiations with Britain's fellow EC members were carried out by Wilson himself in tandem with Foreign Secretary James Callaghan, and they toured the capital cities of Europe meeting their European counterparts. The discussions focused primarily on Britain's net budgetary contribution to the EC. As a small agricultural producer heavily dependent on imports, Britain suffered doubly from the dominance of:

- (i) agricultural spending in the EC budget,

- (ii) agricultural import taxes as a source of EC revenues.

During the renegotiations, other EEC members conceded, as a partial offset, the establishment of a significant European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), from which it was clearly agreed that Britain would be a major net beneficiary.[94]

In the subsequent referendum campaign, rather than the normal British tradition of "collective responsibility", under which the government takes a policy position which all cabinet members are required to support publicly, members of the Government were free to present their views on either side of the question. The electorate voted on 5 June 1975 to continue membership, by a substantial majority.[95]

Asia

American military involvement in Vietnam escalated continuously from 1964 to 1968 and President Lyndon Johnson brought pressure to bear for at least a token involvement of British military units. Wilson consistently avoided any commitment of British forces, giving as reasons British military commitments to the Malayan Emergency and British co-chairmanship of the 1954 Geneva Conference.[96]

His government offered some rhetorical support for the US position (most prominently in the defence offered by the Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart in a much-publicised "teach-in" or debate on Vietnam). On at least one occasion the British government made an unsuccessful effort to mediate in the conflict, with Wilson discussing peace proposals with Alexei Kosygin, the Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers. On 28 June 1966 Wilson 'dissociated' his Government from American bombing of the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong. In his memoirs, Wilson writes of "selling LBJ a bum steer", a reference to Johnson's Texas roots, which conjured up images of cattle and cowboys in British minds.[97]

Part of the price paid by Wilson after talks with President Johnson in June 1967 for US assistance with the UK economy was his agreement to maintain a military presence East of Suez.[98] In July 1967 Defence Secretary Denis Healey announced that Britain would abandon her mainland bases East of Suez by 1977, although airmobile forces would be retained which could if necessary be deployed in the region. Shortly afterward, in January 1968, Wilson announced that the proposed timetable for this withdrawal was to be accelerated, and that British forces were to be withdrawn from Singapore, Malaysia, and the Persian Gulf by the end of 1971.[99]

Wilson was known for his strong pro-Israel views. He was a particular friend of Israeli Premier Golda Meir, though her tenure largely coincided with Wilson's 1970–1974 hiatus. Another associate was West German Chancellor Willy Brandt; all three were members of the Socialist International.[100]

Africa

The British "retreat from Empire" had made headway by 1964 and was to continue during Wilson's administration. Southern Rhodesia was not granted independence, principally because Wilson refused to grant independence to the white minority government headed by Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith which was not willing to extend unqualified voting rights to the native African population. Smith's defiant response was a Unilateral Declaration of Independence, on 11 November 1965. Wilson's immediate recourse was to the United Nations, and in 1965, the Security Council imposed sanctions, which were to last until official independence in 1979. This involved British warships blockading the port of Beira to try to cause economic collapse in Rhodesia. Wilson was applauded by most nations for taking a firm stand on the issue (and none extended diplomatic recognition to the Smith régime). A number of nations did not join in with sanctions, undermining their efficiency. Certain sections of public opinion started to question their efficacy, and to demand the toppling of the régime by force. Wilson declined to intervene in Rhodesia with military force, believing the British population would not support such action against their "kith and kin". The two leaders met for discussions aboard British warships, Tiger in 1966 and Fearless in 1968. Smith subsequently attacked Wilson in his memoirs, accusing him of delaying tactics during negotiations and alleging duplicity; Wilson responded in kind, questioning Smith's good faith and suggesting that Smith had moved the goal-posts whenever a settlement appeared in sight.[97] The matter was still unresolved at the time of Wilson's resignation in 1976.

Defeat and return to opposition, 1970–74

By 1969, the Labour Party was suffering serious electoral reverses, and by the turn of 1970 had lost a total of 16 seats in by-elections since the previous general election.[101]

By 1970, the economy was showing signs of improvement, and by May that year, Labour had overtaken the Conservatives in the opinion polls.[102] Wilson responded to this apparent recovery in his government's popularity by calling a general election, but, to the surprise of most observers, was defeated at the polls by the Conservatives under Heath.

Wilson survived as leader of the Labour party in opposition. In mid-1973, holidaying on the Isles of Scilly, he tried to board a motor boat from a dinghy and stepped into the sea. He was unable to get into the boat and was left in the cold water, hanging on to the fenders of the motor boat. He was close to death before he was saved by passers by. The incident was taken up by the press and resulted in some embarrassment for Wilson; his press secretary, Joe Haines, tried to deflect some of the comment by blaming Wilson's dog for the problem.

Economic conditions during the 1970s were becoming more difficult for Britain and many other western economies as a result of the ending of the Bretton Woods Agreement and the 1973 oil shock, and the Heath government in its turn was buffeted by economic adversity and industrial unrest (notably including confrontation with the coalminers which led to the Three-Day Week) towards the end of 1973, and on 7 February 1974 (with the crisis still ongoing) Heath called a snap election for 28 February.[103]

Second period as Prime Minister (1974–76)

Labour won more seats (though fewer votes) than the Conservative Party in the General Election in February 1974, which resulted in a hung parliament. As Heath was unable to persuade the Liberals to form a coalition, Wilson returned to 10 Downing Street on 4 March 1974 as Prime Minister of a minority Labour Government. He gained a three-seat majority in another election later that year, on 10 October 1974. One of the key issues addressed during his second period in office was the referendum on British membership of the EEC (see Europe, above).

Domestic affairs

The Second Wilson Government made a major commitment to the expansion of the British welfare state, with increased spending on education, health, and housing rents.[69] To pay for it, it imposed controls and raised taxes on the rich. It partially reversed the 1971 reduction in the top rate of tax from 90% to 75%, increasing it to 83% in the first budget from new chancellor Denis Healey, which came into law in April 1974. Also implemented was an investment income surcharge which raised the top rate on investment income to 98%, the highest level since the Second World War.

Despite its achievements in social policy, Wilson's government came under scrutiny in 1975 for the rise in the unemployment rate, with the total number of Britons out of work passing 1,000,000 by that April.[104]

Northern Ireland

Wilson's earlier government had witnessed the outbreak of The Troubles in Northern Ireland. In response to a request from the Government of Northern Ireland, Wilson agreed to deploy the British Army in August 1969 in an effort to restore the peace.

While out of office in late 1971, Wilson had formulated a 16-point, 15-year programme that was designed to pave the way for the unification of Ireland. The proposal was not adopted by the then Heath government.[105]

In May 1974, when back in office as leader of a minority government, Wilson condemned the Unionist-controlled Ulster Workers Council Strike as a "sectarian strike", which was "being done for sectarian purposes having no relation to this century but only to the seventeenth century". He refused to pressure a reluctant British Army to face down the loyalist paramilitaries who were intimidating utility workers. In a televised speech later, he referred to the loyalist strikers and their supporters as "spongers" who expected Britain to pay for their lifestyles. The strike was eventually successful in breaking the power-sharing Northern Ireland executive.

On 11 September 2008, BBC Radio Four's Document programme claimed to have unearthed a secret plan – codenamed Doomsday – which proposed to cut all of the United Kingdom's constitutional ties with Northern Ireland and transform the province into an independent dominion. Document went on to claim that the Doomsday plan was devised mainly by Wilson and was kept a closely guarded secret. The plan then allegedly lost momentum, due in part, it was claimed, to warnings made by both the then Foreign Secretary, James Callaghan, and the then Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Garret FitzGerald who admitted the 12,000-strong Irish army would be unable to deal with the ensuing civil war.[106]

In 1975 Wilson secretly offered Libya's dictator Muammar Gaddafi £14 million (£500 million in 2009 values) to stop arming the IRA, but Gaddafi demanded a far greater sum of money.[107][108] This offer did not become publicly known until 2009.

Resignation

On 16 March 1976, Wilson announced his resignation as Prime Minister (taking effect on 5 April 1976). He claimed that he had always planned on resigning at the age of 60, and that he was physically and mentally exhausted. As early as the late 1960s, he had been telling intimates, like his doctor Sir Joseph Stone (later Lord Stone of Hendon), that he did not intend to serve more than eight or nine years as Prime Minister. Roy Jenkins has suggested that Wilson may have been motivated partly by the distaste for politics felt by his loyal and long-suffering wife, Mary.[13] His doctor had detected problems which would later be diagnosed as colon cancer, and Wilson had begun drinking brandy during the day to cope with stress.[3] In addition, by 1976 he might already have been aware of the first stages of early-onset Alzheimer's disease, which was to cause both his formerly excellent memory and his powers of concentration to fail dramatically.[109]

Queen Elizabeth II came to dine at 10 Downing Street to mark his resignation, an honour she has bestowed on only one other Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill.

Wilson's Prime Minister's Resignation Honours included many businessmen and celebrities, along with his political supporters. His choice of appointments caused lasting damage to his reputation, worsened by the suggestion that the first draft of the list had been written by his political secretary Marcia Williams on lavender notepaper (it became known as the "Lavender List"). Roy Jenkins noted that Wilson's retirement "was disfigured by his, at best, eccentric resignation honours list, which gave peerages or knighthoods to some adventurous business gentlemen, several of whom were close neither to him nor to the Labour Party."[110] Some of those whom Wilson honoured included Lord Kagan, the inventor of Gannex (Wilson's preferred raincoat), who was eventually imprisoned for fraud, and Sir Eric Miller, who later committed suicide while under police investigation for corruption.

The Labour Party held an election to replace Wilson as leader of the Party (and therefore Prime Minister). Six candidates stood in the first ballot; in order of votes they were: Michael Foot, James Callaghan, Roy Jenkins, Tony Benn, Denis Healey and Anthony Crosland. In the third ballot on 5 April, Callaghan defeated Foot in a parliamentary vote of 176 to 137, thus becoming Wilson's successor as Prime Minister and leader of the Labour Party, and he continued to serve as Prime Minister until May 1979, when Labour lost the general election to the Conservatives and Margaret Thatcher became Britain's first female prime minister.

As Wilson wished to remain an MP after leaving office, he was not immediately given the peerage customarily offered to retired Prime Ministers, but instead was created a Knight of the Garter. On leaving the House of Commons after the 1983 general election he was granted a life peerage as Baron Wilson of Rievaulx,[111] after Rievaulx Abbey, in the north of his native Yorkshire.

Retirement and death, 1983–95

Harold Wilson's grave

Shortly after resigning as Prime Minister, Wilson was signed by David Frost to host a series of interview/chat show programmes. The pilot episode proved to be a flop as Wilson appeared uncomfortable with the informality of the format. Wilson also hosted two editions of the BBC chat show Friday Night, Saturday Morning. He famously floundered in the role, and in 2000, Channel 4 chose one of his appearances as one of the 100 Moments of TV Hell.

A lifelong Gilbert and Sullivan fan, in 1975, Wilson joined the Board of Trustees of the D'Oyly Carte Trust at the invitation of Sir Hugh Wontner, who was then the Lord Mayor of London.[112] At Christmas 1978, Wilson appeared on the Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special. Eric Morecambe's habit of appearing not to recognise the guest stars was repaid by Wilson, who referred to him throughout as 'Morry-camby' (the mis-pronunciation of Morecambe's name made by Ed Sullivan when the pair appeared on his famous American television show). Wilson appeared on the show again in 1980.

Wilson was not especially active in the House of Lords, although he did initiate a debate on unemployment in May 1984.[113] His last speech was in a debate on marine pilotage in 1986, when he commented as an elder brother of Trinity House.[114] In the same year he played himself as Prime Minister in an Anglia Television drama, Inside Story.[115]