Book lung

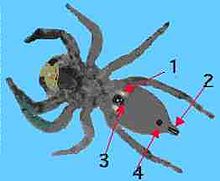

In this spider diagram, the book lung is labelled 1.

Spider book lungs (cross section)

Book lungs of spider (shown in pink)

A book lung is a type of respiration organ used for atmospheric gas exchange that is found in many arachnids, such as scorpions and spiders. Each of these organs is found inside an open ventral abdominal, air-filled cavity (atrium) and connects with the surroundings through a small opening for the purpose of respiration.

Book lungs are not related to the lungs of modern land-dwelling vertebrates. Their name describes their structure. Stacks of alternating air pockets and tissue filled with hemolymph (the arthropod equivalent of blood) give them an appearance similar to a "folded" book.[1](Their number varies from just one pair in most spiders to four pairs in scorpions. The unfolded "pages" (plates) of the book lung are filled with hemolymph.) The folds maximize the surface exposed to air, and thereby maximize the amount of gas exchanged with the environment. In most species, no motion of the plates is required to facilitate this kind of respiration.

Sometimes, book lungs can be absent, and gas exchange is performed by the thin walls inside the cavity instead, with their surface area increased by branching into the body as thin tubes called tracheae. The tracheae possibly have evolved directly from the book lungs because, in some spiders, the tracheae have a small number of greatly elongated chambers. Many arachnids, such as mites and harvestmen (Opiliones), have no traces of book lungs and breathe through tracheae or through their body surfaces only. The absence or presence of book lungs divides the Arachnida into two main groups, the pulmonate arachnids (book lungs present; scorpions and the Tetrapulmonata; whip scorpions, Schizomida, Amblypygi, and spiders), and the apulmonate arachnids (book lungs absent; microwhip scorpions, harvestmen, Acarina, pseudoscorpions, Ricinulei and sunspiders). One of the long-running controversies in arachnid evolution is whether the book lung evolved from book gills just once in a common arachnid ancestor,[2] or whether it evolved in multiple groups of arachnids in parallel as they came onto land.

The oldest book lungs have been recovered from extinct trigonotarbid arachnids preserved in the 410-million-year-old Rhynie chert of Scotland. These Devonian fossil lungs are almost indistinguishable from the lungs of modern arachnids, fully adapted to a terrestrial existence.[3][4]

Book gills

Underside of a female horseshoe crab showing the legs and book gills

It is believed that book lungs evolved from book gills. Although they have a similar book-like structure, book gills are found externally, while book lungs are found internally.[5] Book gills are still found in horseshoe crabs, which have five pairs of them, the flap in front of them being the genital operculum which lacks gills. Book gills are flap-like appendages that effect gas exchange within water and seem to have their origin as modified legs. On the inside of each appendage, over 100 thin leaf-like membranes, lamellae, appearing as pages in a book, are where gas exchange takes place. These appendages move rhythmically to drive blood in and out of the lamellae and to circulate water over them. Respiration being their main purpose, they can also be used for swimming in young individuals. If they are kept moist, the horseshoe crab can live on land for many hours.

In the marine arthropod Limulus, the book gills are developed from the base of the abdominal or opisthosomal appendages.These five pairs of appendages are flap-like and membranous, with the under-surface of each flap formed into many leaf-like folds called lamellae. Thus each gill bears hundreds of thin membranous lamellae arranged like pages in a book.

Each lamella is provided with capillaries separated from the outer sea water by a thin wall that acts as the osmoregulatory membrane.The movement of the organs maintain a constant water flow for gaseous exchange. The oxygen is diffused in from the water and the carbon dioxide is expelled out. The coxae of the last pair of appendages bear short stapulate flagella which helps to clean the gills and serves to sense the oxygen content of the water current.

References

^ Foelix, Rainer F (1996). Biology of Spiders. Oxford University Press US. pp. 61–64. ISBN 0-19-509594-4..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Scholtz, G. & Kamenz, C. (2006) Zoology 109, 2-13; doi:10.1016/j.zool.2005.06.003

^ Kamenz, C. et al. (2008) Biology Letters 4, 212-215; doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0597

^ Microanatomy of Early Devonian book lungs | Biology Letters

^ Bhamrah, H. S.; Kavita Juneja (2002). An Introduction to Arthropoda. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 316. ISBN 81-261-0673-5.