Crankshaft

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Flat-plane crankshaft (red), pistons (gray) in their cylinders (blue), and flywheel (black)

A crankshaft—related to crank—is a mechanical part able to perform a conversion between reciprocating motion and rotational motion. In a reciprocating engine, it translates reciprocating motion of the piston into rotational motion; whereas in a reciprocating compressor, it converts the rotational motion into reciprocating motion. In order to do the conversion between two motions, the crankshaft has "crank throws" or "crankpins", additional bearing surfaces whose axis is offset from that of the crank, to which the "big ends" of the connecting rods from each cylinder attach.

It is typically connected to a flywheel to reduce the pulsation characteristic of the four-stroke cycle, and sometimes a torsional or vibrational damper at the opposite end, to reduce the torsional vibrations often caused along the length of the crankshaft by the cylinders farthest from the output end acting on the torsional elasticity of the metal.

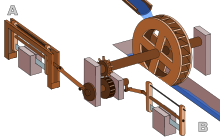

Schematic of operation of a crank mechanism

Contents

1 History

1.1 East Asia

1.1.1 Han China

1.2 Europe

1.2.1 Ancient Rome

1.2.2 Medieval and Renaissance Europe

1.2.3 Modern Europe

1.3 Middle East

2 Internal combustion engines

2.1 Bearings

2.2 Piston stroke

2.3 Engine configuration

2.4 Engine balance

2.5 Flying arms

2.6 Rotary aircraft engines

2.7 Radial engines

3 Construction

3.1 Forging and casting

3.2 Machining

3.2.1 Cleaning and inspection

3.2.2 Stamp counterweight webbing

3.2.3 Undercutting and thermal spraying

3.2.4 Welding

3.2.5 Relieving stress and rechecking for straightness

3.2.6 Crankshaft grinding

3.2.7 Shot peening

3.2.8 Replacing counterweights and determining proper balance

3.2.9 Micro-polishing and testing Rockwell hardness

3.2.10 Final steps

3.3 Microfinishing

3.4 Fatigue strength

3.5 Hardening

3.6 Counterweights

4 Stress on crankshafts

5 Counter-rotating crankshafts

6 See also

7 References

8 Sources

9 External links

History

East Asia

Han China

Tibetan operating a quern (1938). The upright handle of such rotary handmills, set at a distance from the centre of rotation, works as a crank.[1][2]

The earliest hand-operated cranks appeared in China during the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD). They were used for silk-reeling, hemp-spinning, for the agricultural winnowing fan, in the water-powered flour-sifter, for hydraulic-powered metallurgic bellows, and in the well windlass.[3] The rotary winnowing fan greatly increased the efficiency of separating grain from husks and stalks.[4][5] However, the potential of the crank of converting circular motion into reciprocal motion never seems to have been fully realized in China, and the crank was typically absent from such machines until the turn of the 20th century.[6]

Europe

Ancient Rome

Roman crank handle from Augusta Raurica, dated to the 2nd century.[7]

A crank in the form of an eccentrically-mounted handle of the rotary handmill appeared in 5th century BC Celtiberian Spain and ultimately spread across the Roman Empire.[8][1][2] A Roman iron crank dating to the 2nd century AD was excavated in Augusta Raurica, Switzerland.[7][9] The crank-operated Roman mill is dated to the late 2nd century.[10]

Hierapolis sawmill in Asia Minor (3rd century), a machine that combines a crank with a connecting rod.[11]

Evidence for the crank combined with a connecting rod appears in the Hierapolis mill, dating to the 3rd century; they are also found in stone sawmills in Roman Syria and Ephesus dating to the 6th century.[11] The pediment of the Hierapolis mill shows a waterwheel fed by a mill race powering via a gear train two frame saws which cut blocks by the way of some kind of connecting rods and cranks.[12] The crank and connecting rod mechanisms of the other two archaeologically-attested sawmills worked without a gear train.[13][14] Water-powered marble saws in Germany were mentioned by the late 4th century poet Ausonius;[11] about the same time, these mill types seem also to be indicated by Gregory of Nyssa from Anatolia.[15][11][16]

Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Vigevano's war carriage

A rotary grindstone[17] operated by a crank handle is shown in the Carolingian manuscript Utrecht Psalter; the pen drawing of around 830 goes back to a late antique original.[18] Cranks used to turn wheels are also depicted or described in various works dating from the tenth to thirteenth centuries.[17][17][19]

The first depictions of the compound crank in the carpenter's brace appear between 1420 and 1430 in northern European artwork.[20] The rapid adoption of the compound crank can be traced in the works of an unknown German engineer writing on the state of military technology during the Hussite Wars: first, the connecting-rod, applied to cranks, reappeared; second, double-compound cranks also began to be equipped with connecting-rods; and third, the flywheel was employed for these cranks to get them over the 'dead-spot'.[21] The concept was much improved by the Italian engineer and writer Roberto Valturio in 1463, who devised a boat with five sets, where the parallel cranks are all joined to a single power source by one connecting-rod, an idea also taken up by his compatriot Italian painter Francesco di Giorgio.[22]

15th century paddle-wheel boat whose paddles are turned by single-throw crankshafts (Anonymous of the Hussite Wars)

The crank had become common in Europe by the early 15th century, as seen in the works of the military engineer Konrad Kyeser (1366–after 1405).[23][24] Devices depicted in Kyeser's Bellifortis include cranked windlasses for spanning siege crossbows, cranked chain of buckets for water-lifting and cranks fitted to a wheel of bells.[24] Kyeser also equipped the Archimedes' screws for water-raising with a crank handle, an innovation which subsequently replaced the ancient practice of working the pipe by treading.[25] The earliest evidence for the fitting of a well-hoist with cranks is found in a miniature of c. 1425 in the German Hausbuch of the Mendel Foundation.[26]

Pisanello painted a piston-pump driven by a water-wheel and operated by two simple cranks and two connecting-rods.[21] The Italian physician Guido da Vigevano (c. 1280−1349), planning for a new crusade, made illustrations for a paddle boat and war carriages that were propelled by manually turned compound cranks and gear wheels.[27] The Luttrell Psalter, dating to around 1340, describes a grindstone which was rotated by two cranks, one at each end of its axle; the geared hand-mill, operated either with one or two cranks, appeared later in the 15th century.[24]

Medieval cranes were occasionally powered by cranks, although more often by windlasses.[28]

German crossbowman cocking his weapon with a cranked rack-and-pinion device (ca. 1493)

Water-raising pump powered by crank and connecting rod mechanism (Georg Andreas Böckler, 1661)

The 15th century also saw the introduction of cranked rack-and-pinion devices, called cranequins, which were fitted to the crossbow's stock as a means of exerting even more force while spanning the missile weapon (see right).[29] In the textile industry, cranked reels for winding skeins of yarn were introduced.[24]

Around 1480, the early medieval rotary grindstone was improved with a treadle and crank mechanism. Cranks mounted on push-carts first appear in a German engraving of 1589.[30] Crankshafts were also described by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)[31] and a Dutch farmer and windmill owner by the name Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest in 1592. His wind-powered sawmill used a crankshaft to convert a windmill's circular motion into a back-and-forward motion powering the saw. Corneliszoon was granted a patent for his crankshaft in 1597.

Modern Europe

From the 16th century onwards, evidence of cranks and connecting rods integrated into machine design becomes abundant in the technological treatises of the period: Agostino Ramelli's The Diverse and Artifactitious Machines of 1588 depicts eighteen examples, a number that rises in the Theatrum Machinarum Novum by Georg Andreas Böckler to 45 different machines.[32] Cranks were formerly common on some machines in the early 20th century; for example almost all phonographs before the 1930s were powered by clockwork motors wound with cranks. Reciprocating piston engines use cranks to convert the linear piston motion into rotational motion. Internal combustion engines of early 20th century automobiles were usually started with hand cranks, before electric starters came into general use. The 1918 Reo owner's manual describes how to hand crank the automobile:

- First: Make sure the gear shifting lever is in neutral position.

- Second: The clutch pedal is unlatched and the clutch engaged. The brake pedal is pushed forward as far as possible setting brakes on the rear wheel.

- Third: See that spark control lever, which is the short lever located on top of the steering wheel on the right side, is back as far as possible toward the driver and the long lever, on top of the steering column controlling the carburetor, is pushed forward about one inch from its retarded position.

- Fourth: Turn ignition switch to point marked "B" or "M"

- Fifth: Set the carburetor control on the steering column to the point marked "START." Be sure there is gasoline in the carburetor. Test for this by pressing down on the small pin projecting from the front of the bowl until the carburetor floods. If it fails to flood it shows that the fuel is not being delivered to the carburetor properly and the motor cannot be expected to start. See instructions on page 56 for filling the vacuum tank.

- Sixth: When it is certain the carburetor has a supply of fuel, grasp the handle of starting crank, push in endwise to engage ratchet with crank shaft pin and turn over the motor by giving a quick upward pull. Never push down, because if for any reason the motor should kick back, it would endanger the operator.

Middle East

Al-Jazari (1136–1206) described a crank and connecting rod system in a rotating machine in two of his water-raising machines.[31] His twin-cylinder pump incorporated a crankshaft,[33] including both the crank and shaft mechanisms.[34]

Internal combustion engines

Crankshaft, pistons and connecting rods for a typical internal combustion engine

MAN marine crankshaft for 6cyl marine diesel applications. Note locomotive on left for size reference

Large engines are usually multicylinder to reduce pulsations from individual firing strokes, with more than one piston attached to a complex crankshaft. Many small engines, such as those found in mopeds or garden machinery, are single cylinder and use only a single piston, simplifying crankshaft design.

A crankshaft is subjected to enormous stresses, potentially equivalent of several tonnes of force. The crankshaft is connected to the fly-wheel (used to smooth out shock and convert energy to torque), the engine block, using bearings on the main journals, and to the pistons via their respective con-rods. An engine loses up to 75% of its generated energy in the form of friction, noise and vibration in the crankcase and piston area.[citation needed] The remaining losses occur in the valvetrain (timing chains, belts, pulleys, camshafts, lobes, valves, seals etc.) heat and blow by.

Bearings

The crankshaft has a linear axis about which it rotates, typically with several bearing journals riding on replaceable bearings (the main bearings) held in the engine block. As the crankshaft undergoes a great deal of sideways load from each cylinder in a multicylinder engine, it must be supported by several such bearings, not just one at each end. This was a factor in the rise of V8 engines, with their shorter crankshafts, in preference to straight-8 engines. The long crankshafts of the latter suffered from an unacceptable amount of flex when engine designers began using higher compression ratios and higher rotational speeds. High performance engines often have more main bearings than their lower performance cousins for this reason.

Piston stroke

The distance the axis of the crank throws from the axis of the crankshaft determines the piston stroke measurement, and thus engine displacement. A common way to increase the low-speed torque of an engine is to increase the stroke, sometimes known as "shaft-stroking." This also increases the reciprocating vibration, however, limiting the high speed capability of the engine. In compensation, it improves the low speed operation of the engine, as the longer intake stroke through smaller valve(s) results in greater turbulence and mixing of the intake charge. Most modern high speed production engines are classified as "over square" or short-stroke, wherein the stroke is less than the diameter of the cylinder bore. As such, finding the proper balance between shaft-stroking speed and length leads to better results.

Engine configuration

The configuration, meaning the number of pistons and their placement in relation to each other leads to straight, V or flat engines. The same basic engine block can sometimes be used with different crankshafts, however, to alter the firing order. For instance, the 90° V6 engine configuration, in older days[when?] sometimes derived by using six cylinders of a V8 engine with a 3 throw crankshaft, produces an engine with an inherent pulsation in the power flow due to the "gap" between the firing pulses alternates between short and long pauses because the 90 degree engine block does not correspond to the 120 degree spacing of the crankshaft. The same engine, however, can be made to provide evenly spaced power pulses by using a crankshaft with an individual crank throw for each cylinder, spaced so that the pistons are actually phased 120° apart, as in the GM 3800 engine. While most production V8 engines use four crank throws spaced 90° apart, high-performance V8 engines often use a "flat" crankshaft with throws spaced 180° apart, essentially resulting in two straight four engines running on a common crankcase. The difference can be heard as the flat-plane crankshafts result in the engine having a smoother, higher-pitched sound than cross-plane (for example, IRL IndyCar Series compared to NASCAR Sprint Cup Series, or a Ferrari 355 compared to a Chevrolet Corvette). This type of crankshaft was also used on early types of V8 engines. See the main article on crossplane crankshafts.

Engine balance

For some engines it is necessary to provide counterweights for the reciprocating mass of each piston and connecting rod to improve engine balance. These are typically cast as part of the crankshaft but, occasionally, are bolt-on pieces. While counter weights add a considerable amount of weight to the crankshaft, it provides a smoother running engine and allows higher RPM levels to be reached.

Flying arms

Crankshaft with flying arms (the boomerang-shaped link between the visible crank pins)

In some engine configurations, the crankshaft contains direct links between adjacent crank pins, without the usual intermediate main bearing. These links are called flying arms.[35] This arrangement is sometimes used in V6 and V8 engines, as it enables the engine to be designed with different V angles than what would otherwise be required to create an even firing interval, while still using fewer main bearings than would normally be required with a single piston per crankthrow. This arrangement reduces weight and engine length at the expense of less crankshaft rigidity.

Rotary aircraft engines

Some early aircraft engines were a rotary engine design, where the crankshaft was fixed to the airframe and instead the cylinders rotated with the propeller.

Radial engines

The radial engine is a reciprocating type internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinders point outward from a central crankshaft like the spokes of a wheel. It resembles a stylized star when viewed from the front, and is called a "star engine" (German Sternmotor, French Moteur en étoile) in some languages. The radial configuration was very commonly used in aircraft engines before turbine engines became predominant.

Construction

Continental engine marine crankshafts, 1942

Crankshafts can be monolithic (made in a single piece) or assembled from several pieces. Monolithic crankshafts are most common, but some smaller and larger engines use assembled crankshafts.

Forging and casting

Forged crankshaft

Crankshafts can be forged from a steel bar usually through roll forging or cast in ductile steel. Today more and more manufacturers tend to favor the use of forged crankshafts due to their lighter weight, more compact dimensions and better inherent damping. With forged crankshafts, vanadium microalloyed steels are mostly used as these steels can be air cooled after reaching high strengths without additional heat treatment, with exception to the surface hardening of the bearing surfaces. The low alloy content also makes the material cheaper than high alloy steels. Carbon steels are also used, but these require additional heat treatment to reach the desired properties. Cast iron crankshafts are today mostly found in cheaper production engines (such as those found in the Ford Focus diesel engines) where the loads are lower. Some engines also use cast iron crankshafts for low output versions while the more expensive high output version use forged steel.

Machining

Crankshafts can also be machined out of a billet, often a bar of high quality vacuum remelted steel. Though the fiber flow (local inhomogeneities of the material's chemical composition generated during casting) doesn’t follow the shape of the crankshaft (which is undesirable), this is usually not a problem since higher quality steels, which normally are difficult to forge, can be used. These crankshafts tend to be very expensive due to the large amount of material that must be removed with lathes and milling machines, the high material cost, and the additional heat treatment required. However, since no expensive tooling is needed, this production method allows small production runs without high costs.

In an effort to reduce costs, used crankshafts may also be machined. A good core may often be easily reconditioned by a crankshaft grinding [36] process. Severely damaged crankshafts may also be repaired with a welding operation, prior to grinding, that utilizes a submerged arc welding machine. To accommodate the smaller journal diameters a ground crankshaft has, and possibly an over-sized thrust dimension, undersize engine bearings are used to allow for precise clearances during operation.

Machining or remanufacturing crankshafts are precision machined to exact tolerances with no odd size crankshaft bearings or journals. Thrust surfaces are micro-polished to provide precise surface finishes for smooth engine operation and reduced thrust bearing wear. Every journal is inspected and measured with critical accuracy. After machining, oil holes are chamfered to improve lubrication and every journal polished to a smooth finish for long bearing life. Remanufactured crankshafts are thoroughly cleaned with special emphasis to flushing and brushing out oil passages to remove any contaminants. Remanufacturing a crankshaft typically involves the following steps:[37]

Cleaning and inspection

Machine shops soak the crankshafts in a hot tank and power wash the overall shaft. The oil holes are then wire brushed. A magnetic particle inspection checks for cracks. The crankshaft is magnetized and sprayed with an iron oxide powder which, under blacklight conditions, makes any imperfections visible.

The counterweights are removed, cleaned, and checked for cracks and tightness. The bolts of loose counterweights are replaced. The counterweights are then installed back into the crankshafts, which are inspected for damage. A machinist determines the size and hardness of the journals and mains.

A technician checks the keyway, nose, and bolt holes, then seals the surface for non-conformities. Bolt holes are typically tapped ½” or less on remanufactured crankshafts. The bearings and the straightness of the crankshaft are also inspected, and it must be re-straightened with an industrial straightening machine if not up to OEM standards. The straightening machine determines how many dials are out of line. To re-straighten the shaft, technicians heat the crankshaft to 500-600 degrees. Any more than 700 degrees takes the hardness out of the shaft.

The magnetic particle inspection is repeated after the crankshaft has been straightened.

Stamp counterweight webbing

The counterweights and webbing are stamped in proper firing order (alpha if numeric and vice versa). Technicians then stamp the employee ID#, Work Order # and date on #1 rod webbing. Stamping this information on the rod webbing helps keep the quality control process order in case of future issues during the manufacturing process.

Undercutting and thermal spraying

Technicians undercut the rod or journals to eliminate wear before buildup. Further buildup and corrosion is typically prevented via thermal spraying, which involves protrusion of molten particles onto the heated metallic surface, forming a smooth coating interwoven into the structure. Typically, boron alloys are used for this process, as they very dense, hard, and oxide-free. They prevent against abrasive materials that cause divots, scratches, and cracks, and prevent surface erosion and corrosion.

Welding

The welding process for re-manufactured crankshafts is called submerged arc welding. It is a powdered flux plus a weld which combines to produce a more precise weld. The most common flux powder used is called #1 Flux 2245 HD. This powder eliminates the need for technicians to wear weld masking and reduces the amount of dust by-product.

Relieving stress and rechecking for straightness

The crankshaft is once more heated to 500-600 degrees to relieve structural stress. Its overall straightness is also rechecked. If the re-manufactured crankshaft is out of alignment, then the technician must re-straighten the structure.

Crankshaft grinding

Crankshaft grinding involves rough grinding the excess material from the rod or journals. On the rod there are various mains that need to be reground to proper OEM specifications. These rods are spun grind to the next under-size using the pultrusion crankshaft grinding machine. Rod mains are ground inside and outside.

The technician then performs a finished crankshaft grinding procedure, which is a more precise grind which reaches the correct OEM specifications. Before the technician starts the crankshaft grinding they should see what crankshaft bearings are available and start from there. For example, the OEM specification for a Caterpillar 3306 Rod is 2.9987” – 3.0003”. Top industrial crankshaft grinding technicians always stop at the high end of the tolerance level.

Shot peening

Shot peening adds an additional layer of hardness to the re-manufactured crankshaft.

Replacing counterweights and determining proper balance

The counterweights are replaced in proper firing order. Either the new counterweights are installed or the old counterweight bolts are re-tightened.

The machine shop then determines if the proper rotational balance of the re-manufactured crankshafts is achieved. In the engine, the crankshaft, pistons, and rods are all in a constant rotation. The counterweights are designed to offset the weight of the rod and the pistons. When in motion, the kinetic energy and the sum of all forces should be equal to zero on all moving parts. If the counterweights are imbalanced, it adds additional stress on other components of the engine. The technician must ensure that the internal and external balance of the crankshaft counterweights are properly aligned.

Micro-polishing and testing Rockwell hardness

The technician micro-polishes each of the rebuilt crankshafts by hand. To further refine the crankshaft grinding process the machinist makes the most precise fit by micro-polishing the component with a 600-grit emery cloth. Through micro-polishing and industrial crankshaft grinding, the machine shop achieves the recommended Rockwell hardness and Ra finish (Roughness Parameter).

Industry standard crankshaft hardness is 40 on the Rockwell hardness scale. A 45-50 rating is what most reputable machine shops try to employ for all remanufactured crankshafts. Typically, hardness can be reduced if the engine is out of oil or the journal is spun incorrectly.

Final steps

Quality control inspects all of the finished crankshafts mistakes. A typical quality control department uses separate testing and analytical measurement tools from the technicians to ensure accuracy. The remanufactured crankshafts are then rustproofed using Cosmoline and packaged in damage-proof coverings.

Microfinishing

Microfinishing is a method of finishing the surface of the crankshaft in such a manner that microscopic roughness, pitting or cracking is reduced to a smooth, integral surface. Crankshafts fail by fatigue cracking and cracks start at the most highly stressed point in the material, which is the surface. Once a crack has developed, it increases the local stress in the area at its 'V' point, which slowly increases the size of the crack. The objective of microfinishing is to reduce to the smallest number and size any deviation in the surface and thus minimize the opportunity for cracks to develop. Increased requirements on microfinishing has become a common requirement as Industries are moving towards lead-free bearings. Improved performance and longevity are associated with the microfinishing requirements.

Fatigue strength

The fatigue strength of crankshafts is usually increased by using a radius at the ends of each main and crankpin bearing. The radius itself reduces the stress in these critical areas, but since the radius in most cases is rolled, this also leaves some compressive residual stress in the surface, which prevents cracks from forming.

Hardening

Most production crankshafts use induction hardened bearing surfaces, since that method gives good results with low costs. It also allows the crankshaft to be reground without re-hardening. But high performance crankshafts, billet crankshafts in particular, tend to use nitridization instead. Nitridization is slower and thereby more costly, and in addition it puts certain demands on the alloying metals in the steel to be able to create stable nitrides. The advantage of nitridization is that it can be done at low temperatures, it produces a very hard surface, and the process leaves some compressive residual stress in the surface, which is good for fatigue properties. The low temperature during treatment is advantageous in that it doesn’t have any negative effects on the steel, such as annealing. With crankshafts that operate on roller bearings, the use of carburization tends to be favored due to the high Hertzian contact stresses in such an application. Like nitriding, carburization also leaves some compressive residual stresses in the surface.

Counterweights

Some expensive, high performance crankshafts also use heavy-metal counterweights to make the crankshaft more compact. The heavy-metal used is most often a tungsten alloy but depleted uranium has also been used. A cheaper option is to use lead, but compared with tungsten its density is much lower.

Stress on crankshafts

The shaft is subjected to various forces but generally needs to be analysed in two positions. Firstly, failure may occur at the position of maximum bending; this may be at the centre of the crank or at either end. In such a condition the failure is due to bending and the pressure in the cylinder is maximal. Second, the crank may fail due to twisting, so the conrod needs to be checked for shear at the position of maximal twisting. The pressure at this position is the maximal pressure, but only a fraction of maximal pressure.[clarification needed]

Counter-rotating crankshafts

In a conventional piston-crank arrangement in an engine or compressor, a piston is connected to a crankshaft by a connecting rod. As the piston moves through its stroke, the connecting rod varies its angle to the direction of motion of the piston and as the connecting rod is free to rotate at its connection to both the piston and crankshaft, no torque is transmitted by the connecting rod and forces transmitted by the connecting rod are transmitted along the longitudinal axis of the connecting rod. The force exerted by the piston on the connecting rod results in a reaction force exerted by the connecting rod back on the piston. When the connecting rod makes an angle to the direction of motion of the piston, the reaction force exerted by the connecting rod on the piston has a lateral component. This lateral force pushes the piston sideways against the cylinder wall. As the piston moves within the cylinder, this lateral force causes additional friction between the piston and cylinder wall. Friction accounts for approximately 20% of all losses in an internal combustion engine, of which approximately 50% is due to piston cylinder friction [38]

In a paired counter-rotating crankshaft arrangement, lateral forces due to the angle of the connecting rods cancel each other out. This reduces piston-cylinder friction and therefore fuel consumption. The symmetrical arrangement reduces the requirement for counterweights, reducing overall mass and making it easier for the engine to accelerate and decelerate. It also eliminates engine rocking and torque effects. Several counter-rotating crankshaft arrangements have been patented, for example US2010/0263621.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crankshaft. |

- Bicycle crankset

- Brace (tool)

- Cam

- Camshaft

Crankcase, the housing that surrounds the crankshaft- Crankshaft torsional vibration

- Crank (mechanism)

Hudson Motor Car Company, balanced crankshaft in 1916 allowed higher RPM & more power- Piston motion equations

- Tunnel crankshaft

- Sun and planet gear

- Scotch yoke

- swashplate

- wobble plate

References

^ ab Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 159

^ ab Lucas 2005, p. 5, fn. 9

^ Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Pages 118–119.

^ Bautista Paz, Emilio; Ceccarelli, Marco; Otero, Javier Echávarri; Sanz, José Luis Muñoz (2010). A Brief Illustrated History of Machines and Mechanisms. Springer (published May 12, 2010). p. 19. ISBN 978-9048125111..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Du Bois, George (2014). Understanding China: Dangerous Resentments. Trafford on Demand. ISBN 978-1490745077.

^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 104: .mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Yet a student of the Chinese technology of the early twentieth century remarks that even a generation ago the Chinese had not 'reached that stage where continuous rotary motion is substituted for reciprocating motion in technical contrivances such as the drill, lathe, saw, etc. To take this step familiarity with the crank is necessary. The crank in its simple rudimentary form we find in the [modern] Chinese windlass, which use of the device, however, has apparently not given the impulse to change reciprocating into circular motion in other contrivances'. In China the crank was known, but remained dormant for at least nineteen centuries, its explosive potential for applied mechanics being unrecognized and unexploited.

^ ab Schiöler 2009, pp. 113f.

^ Date: Frankel 2003, pp. 17–19

^ Laur-Belart 1988, pp. 51–52, 56, fig. 42

^ Volpert 1997, pp. 195, 199

^ abcd Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161:

Because of the findings at Ephesus and Gerasa the invention of the crank and connecting rod system has had to be redated from the 13th to the 6th c; now the Hierapolis relief takes it back another three centuries, which confirms that water-powered stone saw mills were indeed in use when Ausonius wrote his Mosella.

^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 139–141

^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 149–153

^ Mangartz 2006, pp. 579f.

^ Wilson 2002, p. 16

^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 156, fn. 74

^ abc White, Jr. 1962, p. 110

^ Hägermann & Schneider 1997, pp. 425f.

^ Needham 1986, pp. 112–113.

^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 112

^ ab White, Jr. 1962, p. 113

^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 114

^ Needham 1986, p. 113.

^ abcd White, Jr. 1962, p. 111

^ White, Jr. 1962, pp. 105, 111, 168

^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 167; Hall 1979, p. 52

^ Hall 1979, p. 80

^ Hall 1979, p. 48

^ Hall 1979, pp. 74f.

^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 167

^ ab Ahmad Y Hassan. The Crank-Connecting Rod System in a Continuously Rotating Machine.

^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 172

^ Sally Ganchy, Sarah Gancher (2009), Islam and Science, Medicine, and Technology, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 41, ISBN 1-4358-5066-1

^ Donald Hill (2012), The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, page 273, Springer Science + Business Media

^ Nunney 2007, pp. 16, 41.

^ "Crankshaft Grinding". Crankshaft Repair.

^ "Remanufactured Crankshafts - Capital Reman Exchange". Capital Reman Exchange. Retrieved 2015-12-28.

^ Andersson BS (1991), Company’s perspective in vehicle tribology. In: 18th Leeds-Lyon Symposium (eds D Dowson, CM Taylor and MGodet), Lyon, France, 3-6 September 1991, New York: Elsevier, pp. 503–506

Sources

Hall, Bert S. (1979), The Technological Illustrations of the So-Called "Anonymous of the Hussite Wars". Codex Latinus Monacensis 197, Part 1, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, ISBN 3-920153-93-6

al-Hassan, Ahmad Y.; Hill, Donald R. (1992), Islamic Technology. An Illustrated History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42239-6

Laur-Belart, Rudolf (1988), Führer durch Augusta Raurica (5th ed.), Augst

Mangartz, Fritz (2010), Die byzantinische Steinsäge von Ephesos. Baubefund, Rekonstruktion, Architekturteile, Monographs of the RGZM, 86, Mainz: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, ISBN 978-3-88467-149-8

White, Jr., Lynn (1962), Medieval Technology and Social Change, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press

Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 20: 138–163

Schiöler, Thorkild (2009), "Die Kurbelwelle von Augst und die römische Steinsägemühle", Helvetia Archaeologica, 40 (159/160), pp. 113–124

Wilson, Andrew (2002), "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", The Journal of Roman Studies, 92, pp. 1–32

Nunney, Malcolm J. (2007), Light and Heavy Vehicle Technology (4th ed.), Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, ISBN 978-0-7506-8037-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crankshaft. |

- Interactive crank animation https://www.desmos.com/calculator/8l2kvyivqo

- D & T Mechanisms - Interactive Tools for Teachers (applets) http://www.content.networcs.net/tft/mechanisms.htm

Grewe, Klaus (2009), "Die Reliefdarstellung einer antiken Steinsägemaschine aus Hierapolis in Phrygien und ihre Bedeutung für die Technikgeschichte. Internationale Konferenz 13.−16. Juni 2007 in Istanbul", in Bachmann, Martin, Bautechnik im antiken und vorantiken Kleinasien (PDF), Byzas (in German), 9, Istanbul: Ege Yayınları/Zero Prod. Ltd., pp. 429–454, ISBN 978-975-807-223-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11