Device Forts

| Device Forts | |

|---|---|

| English and Welsh coasts | |

16th-century keep and gun platform at Pendennis Castle | |

| Type | Artillery castles, blockhouses and bulwarks |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | Most |

| Condition | Varied |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1539–47 |

| Built by | Henry VIII |

| In use | 16th–20th centuries |

| Materials | Stone, brick, earth |

| Events | English Civil War, Anglo-Dutch Wars, Napoleonic Wars, First and Second World Wars |

The Device Forts, also known as Henrician castles and blockhouses, were a series of artillery fortifications built to defend the coast of England and Wales by Henry VIII.[a] Traditionally, the Crown had left coastal defences in the hands of local lords and communities but the threat of French and Spanish invasion led the King to issue an order, called a "device", for a major programme of work between 1539 and 1547. The fortifications ranged from large stone castles positioned to protect the Downs anchorage in Kent, to small blockhouses overlooking the entrance to Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire, and earthwork bulwarks along the Essex coast. Some forts operated independently, others were designed to be mutually reinforcing. The Device programme was hugely expensive, costing a total of £376,000 (estimated as between £2 and £82 billion in today's money);[b] much of this was raised from the proceeds of the Dissolution of the Monasteries a few years before.

These utilitarian fortifications were armed with artillery, intended to be used against enemy ships before they could land forces or attack ships lying in harbour. The first wave of work between 1539 and 1543 was characterised by the use of circular bastions and multi-tiered defences, combined with many traditional medieval features. These designs contained serious military flaws, however, and the second period of construction until 1547 saw the introduction of angular bastions and other innovations probably inspired by contemporary thinking in mainland Europe. The castles were commanded by captains appointed by the Crown, overseeing small garrisons of professional gunners and soldiers, who would be supplemented by the local militia in an emergency.

Despite a French raid against the Isle of Wight in 1545, the Device Forts saw almost no action before peace was declared in 1546. Some of the defences were left to deteriorate and were decommissioned only a few years after their construction. After war broke out with Spain in 1569, Elizabeth I improved many of the remaining fortifications, including during the attack of the Spanish Armada of 1588. By the end of the century, the defences were badly out of date and for the first few decades of the 17th century many of the forts were left to decay. Most of the fortifications saw service in the First and Second English Civil Wars during the 1640s and were garrisoned during the Interregnum, continuing to form the backbone of England's coastal defences against the Dutch after Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660. Again left to fall in ruin during the 18th century, many of the Device Forts were modernised and rearmed during the Napoleonic Wars, until peace was declared in 1815.

Fears over a possible French invasion resurfaced several times in the 19th century, combined with rapid changes in technology, such as the development of steamships and shell guns in the 1840s, rifled cannon and iron-clad warships in the 1850s, and torpedo boats in the 1880s. This spurred fresh investment in those Device Forts still thought to be military valuable, and encouraged the decommissioning of others. By 1900, however, developments in guns and armour had made most of the Device Forts that remained in service simply too small to be practical in modern coastal defence. Despite being brought back into use during the First and Second World Wars, by the 1950s the fortifications were finally considered redundant and decommissioned for good. Coastal erosion over the centuries had taken its toll and some sites had been extensively damaged or completely destroyed. Many were restored, however, and opened to the public as tourist attractions.

Contents

1 Early history and design

1.1 Device programme

1.1.1 Background

1.1.2 Initial phase, 1539–43

1.1.3 Second phase, 1544–47

1.2 Architects and engineers

1.3 Architecture

1.4 Logistics

1.5 Garrisons

1.6 Armament

2 Later history

2.1 16th century

2.2 17th century

2.2.1 First English Civil War

2.2.2 Second English Civil War

2.2.3 Interregnum and the Restoration

2.3 18th–19th centuries

2.3.1 1700–91

2.3.2 1792–1849

2.3.3 1850–99

2.4 20th–21st centuries

2.4.1 1900–1945

2.4.2 1946–21st century

3 See also

4 Notes

5 References

6 Bibliography

Early history and design

Device programme

Background

Map of Southern England and Wales showing the locations of the Device Forts:

The Device Forts emerged as a result of changes in English military architecture and foreign policy in the early 16th century.[4] During the late medieval period, the English use of castles as military fortifications had declined in importance.[citation needed] The introduction of gunpowder in warfare had initially favoured the defender, but soon traditional stone walls could easily be destroyed by early artillery.[5] The few new castles that were built during this time still incorporated the older features of gatehouses and crenellated walls, but intended them more as martial symbols than as practical military defences.[6] Many older castles were simply abandoned or left to fall in disrepair.[7]

Although fortifications could still be valuable in times of war, they had played only a limited role during the Wars of the Roses and, when Henry VII invaded and seized the throne in 1485, he had not needed to besiege any castles or towns during the campaign.[8] Henry rapidly consolidated his rule at home and had few reasons to fear an external invasion from the continent; he invested little in coastal defences over the course of his reign.[9] Modest fortifications existed along the coasts, based around simple blockhouses and towers, primarily in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but they were very limited in scale.[10]

His son, Henry VIII inherited the throne in 1509 and took a more interventionist approach in European affairs, fighting one war with France between 1512 and 1514, and then another between 1522 and 1525, this time allying himself with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire.[11] While France and the Empire were in conflict with one another, raids along the English coast might still be common, but a full-scale invasion seemed unlikely.[12] Indeed, traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications.[12] Initially, therefore, Henry took little interest in his coastal defences; he declared reviews of the fortifications in both 1513 and 1533, but not much investment took place as a result.[13]

In 1533 Henry broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and remarry.[14] Catherine was the aunt of King Charles V of Spain, who took the annulment as a personal insult.[15] As a consequence, France and the Empire declared an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraged the two countries to attack England.[16] An invasion of England now appeared certain; that summer Henry made a personal inspection of some of his coastal defences, which had recently been mapped and surveyed: he appeared determined to make substantial, urgent improvements.[17]

Initial phase, 1539–43

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

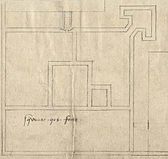

Deal Castle in 2011, and in a draft 1539 plan probably shown to Henry VIII[18]

Henry VIII gave instructions through Parliament in 1539 that new defences were to be built along the coasts of England, beginning a major programme of work that would continue until 1547.[19] The order was known as a "device", which meant a documented plan, instruction or schema, leading to the fortifications later becoming known as the "Device Forts".[20] The initial instructions for the "defence of the realm in time of invasion" concerned building forts along the southern coastline of England, as well as making improvements to the defences of the towns of Calais and Guisnes in France, then controlled by Henry's forces.[20] Commissioners were also to be sent out across south-west and south-east England to inspect the current defences and to propose sites for new ones.[21]

The initial result was the construction of 30 new fortifications of various sizes during 1539.[22] The stone castles of Deal, Sandown and Walmer were constructed to protect the Downs in east Kent, an anchorage which gave access to Deal Beach and on which an invasion force of enemy soldiers could easily be landed.[23] These defences, known as the castles of the Downs, were supported by a line of four earthwork forts, known as the Great Turf Bulwark, the Little Turf Bulwark, the Great White Bulwark of Clay and the Walmer Bulwark, and a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) long defensive ditch and bank.[24] The route inland through a gap in the Kentish cliffs was guarded by Sandgate Castle.[25] In many cases temporary bulwarks for artillery batteries were built in during the initial stages of the work, ahead of the main stonework being completed.[26]

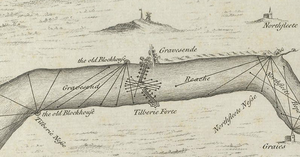

The Thames estuary leading out of London, through which 80 percent of England's exports passed, was protected with a mutually reinforcing network of blockhouses at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on the south side of the river, and West Tilbury and East Tilbury on the opposite bank.[27]Camber Castle was built to protect the anchorage outside the ports of Rye and Winchelsea, defences were built in the port of Harwich and three earth bulwarks were built around Dover.[28] Work was also begun on Calshot Castle in Fawley and the blockhouses of East and West Cowes on the Isle of Wight to protect the Solent, which led into the trading port of Southampton.[29] The Portland Roads anchorage in Dorset was protected with new castles at Portland and Sandsfoot, and work began on two blockhouses to protect the Milford Haven Waterway in Pembrokeshire.[30]

In 1540 additional work was ordered to defend Cornwall.[31]Carrick Roads was an important anchorage at the mouth of the River Fal and the original plans involved constructing five new fortifications to protect it, although only two castles, Pendennis and St Mawes, were actually built, on opposite sides of the estuary.[32] Work began on further fortifications to protect the Solent in 1541, with the construction of Hurst Castle, overlooking the Needles Passage, and Netley Castle just outside Southampton itself.[33] Following a royal visit to the north of England, the coastal fortifications around the town of Hull were upgraded in 1542 with a castle and two large blockhouses.[34] Further work was carried out in Essex in 1543, with a total of seven fortifications constructed, three in Harwich itself, three protecting the estuary leading to the town, and two protecting the estuary linking into Colchester.[35]St Andrew's Castle was begun to further protect the Solent.[36]

The work was undertaken rapidly, and 24 sites were completed and garrisoned by the end of 1540, with almost all of the rest finished by the end of 1543.[37] By the time they were completed, however, the alliance between Charles and Francis had collapsed and the threat of imminent invasion was over.[38]

Second phase, 1544–47

Southsea Castle in 2011, and depicted in the Cowdray engraving of the Battle of the Solent in 1545

Henry moved back onto the offensive in Europe in 1543, allying himself with Spain against France once again.[39] Despite Henry's initial successes around Boulogne in northern France, King Charles and Francis made peace in 1544, leaving England exposed to an invasion by France, backed by her allies in Scotland.[40] In response Henry issued another device in 1544 to improve the country's defences, particularly along the south coast.[41] Work began on Southsea Castle in 1544 on Portsea Island to further protect the Solent, and on Sandown Castle the following year on the neighbouring Isle of Wight.[42]Brownsea Castle in Dorset was begun in 1545, and Sharpenrode Bulwark was built opposite Hurst Castle from 1545 onwards.[43]

The French invasion emerged in 1545, when Admiral Claude d'Annebault crossed the Channel and arrived off the Solent with 200 ships on 19 July.[44] Henry's fleet made a brief sortie, before retreating safely behind the protective fortifications.[45] Annebault landed a force near Newhaven, during which Camber Castle may have fired on the French fleet, and on 23 July they landed four detachments on the Isle of Wight, including a party that took the site of Sandown Castle, which was still under construction.[46] The French expedition moved further on along the coast on 25 July, bringing an end to the immediate invasion threat.[47] Meanwhile, on 22 July the French had carried out a raid at Seaford, and Camber Castle may have seen action against the French fleet.[48] A peace treaty was agreed in June 1546, bringing an end to the war.[49] By the time that Henry died the following year, in total the huge sum of £376,000 had been spent on the Device projects.[50][b]

Architects and engineers

Yarmouth Castle in 2009, and its 1559 plan showing its Italianate, arrow-head bastion

Some of the Device Forts were designed and built by teams of English engineers.[51] The master mason John Rogers was brought back from his work in France and worked on the Hull defences, while Sir Richard Lee, another of the King's engineers from his French campaigns, may have been involved in the construction of Sandown and Southsea; the pair were paid the substantial sums of £30 and £36 a year respectively.[52][b] Sir Richard Morris, the Master of Ordnance, and James Needham, the Surveyor of the King's Works, led on the defences along the Thames.[51] The efforts of the Hampton Court Palace architectural team, under the leadership of the Augustinian canon, Richard Benese, contributed to the high-quality construction and detailing seen in many of Henry's Device projects.[53]

Henry himself took a close interest in the design of the fortifications, sometimes overruling his technical advisers on particular details.[54] Southsea Castle, for example, was described by the courtier Sir Edmund Knyvet as being "of his Majesty's own device", which typically indicated that the King had taken a personal role in its design.[55] The historian Andrew Saunders suspects that Henry was "probably the leading and unifying influence behind the fortifications".[51]

England also had a tradition of drawing on expert foreign engineers for military engineering; Italians were particularly sought after, as their home country was felt to be generally more technically advanced, particularly in the field of fortifications.[56] One of these foreign engineers, Stefan von Haschenperg from Moravia, worked on Camber, Pendennis, Sandgate and St Mawes, apparently attempting to reproduce Italian designs, although his lack of personal knowledge of such fortifications impacted poorly on the end results.[57] Technical treatises from mainland Europe also influenced the designers of the Device Forts, including Albrecht Dürer's Befestigung der Stett, Schlosz und Felcken which described contemporary methods of fortification in Germany, published in 1527 and translated into Latin in 1535, and Niccolò Machiavelli's Libro dell'art della guerra, published in 1521, which also described new Italian forms of military defences.[58]

Architecture

18th-century engraving of a 1588 map showing the mutually reinforcing defences along the River Thames, including Milton and Gravesend blockhouses (top), and East Tilbury and West Tilbury blockhouses (bottom)[c]

The Device Forts represented a major, radical programme of work; the historian Marcus Merriman describes it as "one of the largest construction programmes in Britain since the Romans", Brian St John O'Neil as the only "scheme of comprehensive coastal defence ever attempted in England before modern times", while Cathcart King likened it to the Edwardian castle building programme in North Wales.[59]

Although some of the fortifications are titled as castles, historians typically distinguish between the character of the Device Forts and those of the earlier medieval castles.[60] Medieval castles were private dwellings as well as defensive sites, and usually played a role in managing local estates; Henry's forts were organs of the state, placed in key military locations, typically divorced from the surrounding patterns of land ownership or settlements.[60] Unlike earlier medieval castles, they were spartan, utilitarian constructions.[61] Some historians such as King have disagreed with this interpretation, highlighting the similarities between the two periods, with the historian Christopher Duffy terming the Device Forts the "reinforced-castle fortification".[62]

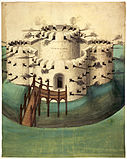

The forts were positioned to defend harbours and anchorages, and designed both to focus artillery fire on enemy ships, and to protect the gunnery teams from attack by those vessels.[63] Some, including the major castles, including the castles of the Downs in Kent, were intended to be self-contained and able to defend themselves against attack from the land, while the smaller blockhouses were primarily focused on the maritime threat.[64] Although there were extensive variations between the individual designs, they had common features and were often built in a consistent style.[65]

The larger sites, such as Deal or Camber, were typically squat, with low parapets and massively thick walls to protect against incoming fire.[66] They usually had a central keep, echoing earlier medieval designs, with curved, concentric bastions spreading out from the centre.[67] The main guns were positioned over multiple tiers to enable them to engage targets at different ranges. There were far more gunports than there were guns held by the individual fortification.[68] The bastion walls were pierced with splayed gun embrasures, giving the artillery space to traverse and enabling easy fire control, with overlapping angles of fire.[69] The interiors had sufficient space for gunnery operations, with specially designed vents to remove the black powder smoke generated by the guns.[70]Moats often surrounded the sites, to protect against any attack from land, and they were further protected by what the historian B. Morley describes as the "defensive paraphernalia developed in the Middle Ages": portcullises, murder holes and reinforced doors.[71] The smaller blockhouses took various forms, including D-shapes, octagonal and square designs.[72] The Thames blockhouses were typically protected on either side by additional earthworks and guns.[73]

These new fortifications were the most advanced in England at the time, an improvement over earlier medieval designs, and were effective in terms of concentrating firepower on enemy ships.[74] They contained numerous flaws, however, and were primitive in comparison to their counterparts in mainland Europe.[75] The multiple tiers of guns gave the forts a relatively high profile, exposing them to enemy attack, and the curved surfaces of the hollow bastions were vulnerable to artillery.[76] The concentric bastion design prevented overlapping fields of fire in the event of an attack from the land, and the tiers of guns meant that, as an enemy approached, the number of guns the fort could bring to bear diminished.[77]

Some of these issues were addressed during the second Device programme from 1544 onwards. Italian ideas began to be brought in, although the impact of Henry's foreign engineers seems to have been limited, and the designs themselves lagged behind those used in his French territories.[78] The emerging continental approach used angled, "arrow-head" bastions, linked in a line called a trace italienne, to provide supporting fire against any attacker.[79] Sandown Castle on the Isle of Wight, constructed in 1545, was a hybrid of traditional English and continental ideas, with angular bastions combined with a circular bastion overlooking the sea.[80] Southsea Castle and Sharpenode Fort had similar, angular bastions.[81] Yarmouth Castle, finished by 1547, was the first fortification in England, to adopt the new arrow-headed bastion design, which had further advantages over a simple angular bastion.[82] Not all the forts in the second wave of work embraced the Italian approach however, and some, such as Brownsea Castle, retained the existing, updated architectural style.[80]

Logistics

Calshot Castle in 2012 (left) and in a 1539 plan (right); the castle reused materials from the dissolution of nearby Beaulieu Abbey

The costs of building the fortifications varied with their size.[83] A small blockhouse cost around £500 to build, whereas a medium-sized castle, such as Sandgate, Pendennis or Portland, would come to approximately £5,000.[83] The defensive line of Deal, Sandown and Walmer castles cost a total £27,092, while the work at Hull Castle and its two blockhouses came to £21,056.[84][b] Various officials were appointed to run each of the projects, including a paymaster, a comptroller, an overseer and commissioners from the local gentry.[85] A few fortifications were built by local individuals and families; St Catherine's Castle, for example, was reportedly paid for by the town and local gentry, and the Edgcumbe family built Devil's Point Artillery Tower to protect Plymouth Harbour.[86]

Much of the expenditure was on the construction teams, called "crews", who built the forts.[50] The numbers of workers varied during the course of the project, driven in part by seasonal variation, but the teams were substantial: Sandgate Castle, for example, saw an average of 640 men on the site daily during June 1540, and the work at Hull required a team of 420.[87] A skilled worker was paid between 7 and 8 pence a day, a labourer between 5 and 6 pence, with trades including stonemasons, carpenters, carters, lime burners, sawyers, plumbers, scavelmen, dikers and bricklayers.[88][d] Finding enough workers proved difficult, and in some cases men had to be pressed into service unwillingly.[89]Labour disputes broke out, with strikes over low pay at Deal in 1539 and at Guisnes in 1541; both were quickly suppressed by royal officials.[90]

Large amounts of raw materials were also needed for the work, including stone, timber and lead and many other supplies. Camber, for example, probably required over 500,000 bricks, Sandgate needed 44,000 tiles, while constructing a small blockhouse along the Thames was estimated by contemporaries to require 200 tonnes (200 long tons; 220 short tons) of chalk just to enable the manufacture of the lime mortar.[91] Some materials could be sourced locally, but coal was shipped from the north of England and prefabricated items were brought in from London.[92]

Most of the money for the first phase of Device works came from Henry's dissolution of the monasteries a few years before, and the revenues that flowed in from the Court of Augmentations and First Fruits and Tenths as a result.[93] In addition, the dissolution had released ample supplies of building materials as the monastic buildings were pulled down, and much of this was recycled.[94] Netley Castle, for example, was based on an old abbey and reused many of its stones, East Tilbury Blockhouse reused parts of St Margaret's Chantry, Calshot Castle took the lead from nearby Beaulieu Abbey, East and West Cowes castles stone from Beaulieu and Quarr, and Sandwich had the stone from the local Carmelite friary.[95] Milton Blockhouse was constructed on land that had recently been confiscated from Milton Chantry.[96] By the second phase of the programme, however, most of the money from the dissolution had been spent, and Henry instead had to borrow funds; government officials noted that at least £100,000 was needed for the work.[39][b]

Garrisons

Reconstruction of life amongst the 16th-century garrison at St Mawes Castle

The garrisons of the Device Forts comprised relatively small teams of men who typically lived and worked in the fortifications.[97] The garrisons would maintain and care for the buildings and their artillery during the long periods of peacetime and, in a crisis, would be supplemented by additional soldiers and the local militia.[97] The size of the garrisons varied according to the fortification; Camber Castle had a garrison of 29, Walmer Castle 18, while the West Tilbury Blockhouse only held 9 men.[98] The ordinary soldiers would have lived in relatively basic conditions, typically on the ground floor, with the captains of the fortifications occupying more elaborate quarters, often in the upper levels of the keeps.[99] The soldiers ate meat and fish, some of which might have been hunted or caught by the garrison.[100]

The garrisons were well organised, and a strict code of discipline was issued in 1539; the historian Peter Harrington suggests that life in the forts would have usually been "tedious" and "isolated".[101] Soldiers were expected to provide handguns at their own expense, and could be fined if they failed to produce them.[102] There were only around 200 gunners across England during the 1540s; they were important military specialists, and the historians Audrey Howes and Martin Foreman observe that "an air of mystery and danger" surrounded them.[103]

The rates of pay across the defences were recorded in 1540, showing that the typical pay of the garrisons was 1 or 2 shillings a day for a captain; his deputy, 8 pence; porters, 8 pence; with soldiers and gunners receiving 6 pence each.[104][b] In total, 2,220 men were recorded as receiving pay that year, at a cost to the Crown of £2,208.[105] Although most garrisons were paid for by the Crown, in some cases the local community also had a role; at Brownsea, the local town was responsible for providing a garrison of 6 men, and at Sandsfoot the village took up the responsibility for supporting the castle garrison, in exchange for an exemption from paying taxes and carrying out militia service.[106]

Armament

Reconstruction of a 16th-century cannon and gun crew at Pendennis Castle

The artillery guns in the Device forts were the property of the Crown and were centrally managed by the authorities in the Tower of London.[105] The Tower moved them between the various fortifications as they felt necessary, often resulting in complaints from the local captains.[105] Various surviving records record the armaments held by individual forts on particular dates, and between 1547 and 1548 a complete inventory was made of the Crown's possessions, detailing the weapons held by all of the forts.[107] The number of guns varied considerably from site to site; in the late 1540s, heavily armed forts such as Hurst and Calshot held 26 and 36 guns respectively; Portland, however, had only 11 pieces.[108] Some forts had more guns than the level of their regular, peace-time garrison; for example, despite only having an establishment of 13 men, Milton Blockhouse had 30 artillery pieces.[109]

A variety of artillery guns were deployed, including heavier weapons, such as cannons, culverins and demi-cannons, and smaller pieces such as sakers, minions and falcons.[110] Some older guns, for example slings and bases, were also deployed, but were less effective than newer weapons such as the culverin.[110] With sites equipped with several tiers of weapons, the heaviest guns would typically be placed higher up in the fortification, with the smaller weapons closer to the ground.[70] It is uncertain how far the guns of the period would have reached; analysis carried out in the 16th and 17th century on the ranges of artillery suggested that the largest weapons, such as a culverin, could hit a target up to between 1,600 and 2,743 metres (5,200 ft and 8,999 ft) away.[111]

The forts were typically equipped with a mixture of brass and iron artillery guns.[112] Guns made of brass could fire more quickly—up to eight times an hour—and were safer to use than their iron equivalents, but were expensive and required imported copper.[113] In the 1530s Henry had established a new English gun-making industry in the Weald of Kent and London, staffed by specialists from mainland Europe.[114] This could make cast-iron weapons, but probably initially lacked the capacity to supply all of the artillery required for the Device forts, particularly since Henry also required more guns for his new navy.[115] A technical breakthrough in 1543, however, led to the introduction of vertical casting and a massive increase in Henry's ability to manufacture iron cannons.[116] Few guns from this period have survived, but during excavations in 1997 an iron portpiece was discovered on the site of the South Blockhouse in Kingston on Hull.[117] The weapon, now known as "Henry's Gun", is one of only four such guns in the world to have survived and is displayed at the Hull Museums.[117]

In addition to artillery, the Device Forts were equipped with infantry weapons.[107] Handguns, typically an early form of matchlock arquebus called a hagbush, would have been used for close defence; these were 6-foot (1.8 m) long and supported on tripods.[107] Many forts also held supplies of bows, arrows and polearms, such as bills, pikes and halberds.[118]Longbows were still in military use among English armies in the 1540s, although they later declined quickly in popularity, and these, along with the polearms, would have been used by the local militia when they were called out in a crisis.[119]

Later history

16th century

Walmer Castle in 2011 (left) and a 1539 plan for either Walmer or Sandown Castle (right) [120]

After Henry's death there was a pause in the conflict with France, during which many of the new fortifications were alllowed to deteriorate.[121] There was little money available for repairs and the garrisons were reduced in size.[122] East Cowes was abandoned around 1547 and fell into ruin, while the bulwarks along the Downs were defaced and their guns removed; they were formally removed from service in 1550.[123] In 1552 the Essex fortifications were decommissioned, and several were subsequently pulled down.[124] The expense of maintaining the fortifications in Hull led the Crown to agree a deal with the town authorities to take over management of them.[125] Milton and Higham were demolished between 1557 and 1558.[126] Mersea Fort was temporarily decommissioned, before being brought back into active service.[124]

The strategic importance of south-east England declined after peace was declared with France in 1558.[127] Military attention instead shifted towards the Spanish threat to the increasingly prosperous south-west of the country; tensions grew and war finally broke out in 1569.[127] The new threat led to improvements being made to Pendennis and St Mawes castles in Cornwall, and repairs to Calshot, Camber and Portland along the south coast.[128] In 1588 the Spanish armada sailed for England and the Device Forts were mobilised in response.[129] As part of this work, West Tilbury was brought back into service and supported by a hastily raised army, which was visited by Queen Elizabeth I, and further enlargement followed under the direction of the Italian engineer, Federigo Giambelli.[130] Gravesend was improved and several of the Essex fortifications were temporarily brought back into use; there were discussions about enhancing the defences at Hull and Milford Haven, but no work was actually carried out.[131]

Despite the destruction of the Armada, the Spanish threat continued;[132] the castles in Kent were kept ready for action throughout the rest of Elizabeth's reign.[133] In 1596 a Spanish invasion fleet carrying reportedly 20,000 soldiers set out for Pendennis, which was then garrisoned with only 500 men.[134] The fleet was forced to turn back due to bad weather, but Elizabeth reviewed the defences and significantly expanded Henry's original fortifications with more up-to-date bastions, designed by the engineer Paul Ive.[135] By the end of the century, however, most of the Device Forts were typically out of date by European standards.[136]

17th century

James I came to the English throne in 1603, resulting peace with both France and Spain.[137] His government took little interest in the coastal defences and many of the Device Forts were neglected and fell into disrepair, with their garrisons' wages left unpaid.[138] Castles such as Deal and blockhouses like Gravesend were all assessed as needing extensive repairs, with Sandgate reported to be in such a poor condition that "neither habitable or defensible against any assault, nor any way fit to command the roads".[139] Lacking ammunition and powder, and with only a handful of its guns in adequate repair, Hurst was unable to prevent Flemish ships from passing along the Solent.[140] Pendennis's garrison's pay was two years in arrears, reportedly forcing them to gather limpets from the shoreline for food.[141] Some of the forts fell out of use; Camber Castle, whose original function of protecting the local anchorage had by now been made redundant by the changing shoreline, was decommissioned by King Charles I in 1637, while Sharpenrode Bulwark lay in ruins by the 1620s.[142]

First English Civil War

Sketch of the Gravesend Blockhouse, by Cornelis Bol, mid-17th century

Civil war broke out across England in 1642 between the supporters of King Charles I and Parliament. Fortifications and artillery played an important role in the conflict, and most of the Device Forts saw service.[143] The south and east of England were soon largely controlled by Parliament.[144] The blockhouses at Gravesend and Tilbury were garrisoned by Parliament and used to control access to London.[145] The castles along the Sussex and Kentish coastline were seized by Parliament in the opening phase of the war, Camber Castle then being decommissioned to prevent it being used by the enemy, the remainder continuing to be garrisoned.[146] The royal fleet, which had been positioned in the Downs anchorage, sided with Parliament.[147]

The Device Forts along the Solent also fell into Parliamentary hands early in the conflict. Calshot was garrisoned throughout, as was Brownsea, which was strengthened and equipped with additional guns.[148] West Cowes was rapidly taken after firing on a nearby Parliamentary ship, and the Royalist commander at Yarmouth quickly negotiated a surrender of his tiny garrison.[149] The heavily outnumbered garrison at Southsea Castle was stormed by Parliamentary forces in a night attack.[150] Like Camber, St Andrew's and Netley were rapidly occupied and then decommissioned by Parliament.[151] In the north-east, Hull also sided with Parliament, and its castle and blockhouses were used as part of the town's defences during multiple sieges.[152]

Much of the south-west sided with the King; Device Forts such as St Catherine's were held by the Royalists from the beginning of the conflict.[153] The Royalists invaded Parliamentary-controlled Dorset in 1643, taking Portland and Sandsfoot.[154] The flow of the war turned against the King, and the Dorset forts were besieged in 1644 and 1645, with Sandsfoot falling to Parliament.[155] By March 1646, Thomas Fairfax had entered Cornwall with a substantial army.[156] The captain of the castle was invited to retreat to the stronger fortress of Pendennis, but he surrendered immediately without putting up resistance.[157] Pendennis was bombarded from the land and blockaded by a flotilla of ships.[158] The captain, Sir John Arundell, agreed to an honourable surrender on 15 August, and around 900 survivors left the fort, some terminally ill from malnutrition.[159] Pendennis was the penultimate Royalist fortification to hold out in the war, followed by Portland Castle which finally surrendered in April 1646.[160]

Second English Civil War

Little Dennis Blockhouse in 2008

After a few years of unsteady peace, in 1648 the Second English Civil War broke out, this time with Charles' Royalist supporters joined by Scottish forces. The Parliamentary navy was based in the Downs, protected by the nearby Henrician castles, but by May a Royalist insurrection was underway across Kent.[161] Sandown Castle declared for the King, and the soldier and former naval captain Major Keme then convinced the garrisons at Deal and Walmer to surrender.[162] Sandgate Castle probably joined the Royalists as well.[163] With both the coastal fortresses and the navy now under Royalist control, Parliament feared that foreign forces might be landed along the coast, or military aid sent to the Scots.[164]

Essex also rose in rebellion in June and the town of Colchester was taken by the Royalists.[165] Sir Thomas Fairfax placed it under siege, and Mersea Fort was taken by Parliamentary forces and used to cut off any assistance reaching the town by river.[165] Meanwhile, Parliament defeated the Kentish insurgency at the Battle of Maidstone at the start of June and then sent a force under the command of Colonel Rich to deal with the castles of the Downs.[166]

Walmer Castle was the first to be besieged and surrendered on 12 July.[167] An earthwork fort was then built between Sandown and Deal, who each may have been defended by around 150 men each.[167] Deal, which had been resupplied by the Royalists from the sea, was besieged in July.[168] A Royalist fleet bombarded the Parliamentary positions and temporarily landed a force 1,500 Flemish mercenaries in support of the revolt, but a shortage of money forced their return to the Continent.[169] The fleet, under the command of Prince Charles, attempted to landed a fresh force in August, but despite three attempts the operation failed and suffered heavy losses.[170] Deal surrendered on 25 August, followed by Sandown on 5 September.[171]

Interregnum and the Restoration

The South Blockhouse (centre) and Castle (right) at Hull, viewed from the sea, by Wenceslas Hollar, mid-17th century

Unlike many castles, the Device Forts avoided being slighted – deliberately damaged or destroyed – by Parliament during the years of the Interregnum.[172] Many of the forts remained garrisoned with substantial numbers of men due to fears of a Royalist invasion, overseen by newly appointed governors; Netley was brought back into service due to the threat.[173] Many were used to hold prisoners of war or political detainees, including Hull, Mersea, Portland, Southsea and West Cowes.[174] During the First Anglo-Dutch War between 1652 and 1654, castles such as Deal were reinforced with earthworks and soldiers.[175] Portland saw action during a three-day long naval battle between English and Dutch forces in the Portland Roads.[176] Some sites fell out of use: Little Dennis Blockhouse – part of the complex of defences at Pendennis – and Mersea were decommissioned between 1654 and 1655, and Brownsea Castle was sold off into private hands.[177]

Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 and reduced both the size and the wages of the garrisons across the kingdom.[178] The Device Forts initially remained at the heart of the defences along the south coast, but their design was by now badly antiquated.[179] Deal continued to play an important role in defending the Downs during the Second and Third Dutch Wars, supported by local trained bands, and castles such as Hurst, Portland and Sandgate remained garrisoned.[180] Others, however, were decommissioned with Sandsfoot closing in 1665 following a dispute over the control of the defences, and Netley being abandoned to fall into ruin.[181]

Concerns about the Dutch threat were intensified after an unexpected naval raid along the Thames in 1667, during which Gravesend and Tilbury prevented the attack reaching the capital itself.[182] In response, Charles made extensive improvements to his coastal defences.[183] As part of this investments were made to Pendennis, Southsea and Yarmouth, while Tilbury was hugely expanded with an updated system of ramparts, bastions and moats at considerable cost.[184] In the final phases of Charles's work, the castle and southern blockhouse at Hull were incorporated into a massive new fortification called the Citadel during the 1680s.[185]

Some of the Device Forts played a role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 against Charles' brother, King James II. The townsfolk of Deal seized their local castle in support of William of Orange, and took steps to defend the Downs against a feared Irish invasion which never materialised.[186] Southsea Castle was held by the King's illegitimate son, James FitzJames, the Duke of Berwick, who was pressurised into surrendering as his father's cause collapsed.[187] Yarmouth was controlled by Robert Holmes, a supporter of James, but was prevented from actively supporting the loyalist cause by the local inhabitants and his garrison, who sided with William.[188]

18th–19th centuries

1700–91

St Mawes Castle (centre) and Pendennis (left) depicted by J. M. W. Turner in 1823

The military significance of the Device Forts declined during the 18th century.[172] Some of the fortifications were redesigned to provide more comfortable housing for their occupants. Cowes Castle was partially rebuilt in 1716 to modernise its accommodation, demolishing much of the keep and adding residential wings and gardens over the landward defences, and Brownsea Castle began to be converted into a country house from the 1720s onwards.[189] Walmer became the official residence of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, and Lionel Sackville, the Duke of Dorset, carried out extensive work there after 1708.[190] There was probably some rivalry between Sackville and the naval officer Sir John Norris, who redeveloped nearby Deal Castle during the same period, creating comfortable wood-panelled quarters for himself there overlooking the sea.[190]

Criticisms were levelled at the defences of the Device Forts, which often had minimal garrisons and had been left to fall into disrepair.[172] Southsea Castle, for example, was only garrisoned by "an old sergeant and three or four men who sell cakes and ale" according to one contemporary account, and proposals were put forward to abandon the site altogether.[191] Portland suffered badly from coastal erosion and, protected only by a caretaker garrison, was reportedly not repaired for many years, and a 1714 survey found the long-neglected Pendennis Castle to be "in a very ruinous condition".[192] The French military dismissed Deal, Walmer and Sandown as being highly vulnerable to any potential attack, describing them in 1767 as "very old and little more than gun platforms".[193] Mersea Fort and East Tilbury fell into ruin and were abandoned, the latter being submerged by the Thames.[194] Some limited investments were made in the fortifications, however, with the defences of Pendennis Castle being modernised in the 1730s, and those of Calshot in the 1770s.[195]

1792–1849

The Duke of Wellington's room in Walmer Castle; the Duke was captain there between 1829 and 1852

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries led to some of the castles being re-garrisoned and improved, as part of the development of a range of gun batteries around key locations.[196] Some of the fortifications such as Sandgate, Southsea, Hurst and Pendennis, protected strategic locations and these were extensively modernised.[197] Hurst, for example, was redesigned with batteries of heavier 36-pounder (16.3 kg) weapons, and Pendennis was equipped with up to 48 guns.[198] Sandgate's keep was rebuilt to form a Martello tower as part of a wider programme of work along the south coast.[199] New gun batteries were constructed at Deal, Sandown in Kent and Tilbury, while Fort Mersea was brought back into service complete with a new battery as well.[200] Calshot Castle was renovated, Southsea's defences were extensively modernised, as were those in Hull, with the castle and the south blockhouse being refitted.[201]

Some of the Device Forts worked in conjunction with the volunteer units raised during the wars to counter the threat of a French invasion.[202] Walmer Castle was used by its captain William Pitt the Younger – then both the Prime Minister and the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports – as the base for volunteer cavalry unit and a fleet of 35 armed fishing boats called luggers.[203] Nearby Deal also had units of infantry and cavalry, called fencibles and in 1802 units of bombardiers recruited by Pitt carried out military exercises at the castle.[204] Calshot was used to store munitions for nearby Sea Fencibles.[205] Pendennis held a new volunteer artillery unit, which was used to train other garrisons across Cornwall.[206]

The government coastguard used some of the fortifications as bases to combat smuggling.[207] Calshot was a good location for interception vessels to lie in wait and, by the middle of the century, two officers and forty-two men were stationed there; Sandown Castle in Kent was also used by the coastguard for anti-smuggling operations.[208] In the coming decades some forts were declared obsolete and put to new uses; Portland was disarmed after the war and converted into a private house.[209] Gravesend was superseded by the New Tavern Fort and demolished in 1844.[210] Meanwhile, the ruins of Netley Castle were transformed into a Gothic-styled house from 1826 onwards.[211]

1850–99

Hurst Castle seen from the east, showing the 16th-century defences (centre) flanked by extensive mid-19th century additions

From the mid-19th century onwards, changes in military technology repeatedly challenged the value and composition of Britain's coastal defences. The introduction of shell guns and steam ships created a new risk that the French might successfully attack along the south coast, and fears grew of a conflict in the early 1850s.[212][e] Southsea Castle and St Mawes were extended with new gun batteries, Pendennis was reequipped with heavier guns and Hurst was extensively redeveloped.[214] There were discussions about rearming Calshot, but these were rejected, in part due to concerns about the suitability of the 16th-century walls in modern warfare.[215][f] The Crimean War sparked a fresh invasion scare and in 1855 the south coast of England was refortified.[216] New guns were installed at St Catherine's and Yarmouth in 1855.[217] The remains of the West Blockhouse were destroyed by a new fortification, the West Blockhouse Fort, designed to deal with the French threat.[218]

Fresh worries about France, combined with the development of rifled cannon and iron-clad warships, led to the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom being established in 1859, and expressing fears about the security of the south coast.[219] In response, Sandgate was re-equipped with heavier guns in 1859, and extensive work was carried out on Southsea.[220] Hurst was fitted with two huge batteries of heavy rifled breech-loading guns, protected by iron armour-plate, intended for use against fast-moving enemy warships.[221] Tilbury Blockhouse was destroyed to make way for heavier guns at the fort after 1868.[222] Portland was readopted by army as a garrison base in 1869 in response to fears of an invasion, but it was not rearmed.[223]

A fresh wave of concerns about France followed in the 1880s, accompanied by the introduction of still more powerful naval artillery and fast warships and torpedo boats, resulting in a fresh wave of modernisation.[224] An electronically-operated minefield was laid across Carrick Roads in 1885, jointly controlled from St Mawes and Pendennis.[225] New, quick-firing guns were installed at Hurst to enable the castle to engage the newer vessels.[226] Calshot was brought back into service as a coastal fort, with a new battery of quick-firing guns protecting a boom across the estuary.[227] The original 16th-century parts of fortifications such as Southsea and Calshot were too small and unsuitable for modern weapons, however, and were instead used for mounting searchlights, range and direction finding; in some cases their fabric was left to slowly decline.[228]

Some other sites were no longer considered viable at all. West Cowes was decommissioned in 1854 and became the club house of the Royal Yacht Squadron.[229] Sandown Castle in Kent, suffering badly from coastal erosion, began to be demolished from 1863 onwards; Hull Citadel and its 16th-century fortifications were demolished in 1864 to make way for docks; Yarmouth was decommissioned in 1885, becoming a coastguard signalling station; and Sandgate, also suffering from coastal erosion, was sold off to the South Eastern Railway company in 1888.[230]

20th–21st centuries

1900–1945

6-inch (152 mm) Mark 24 gun in the Half Moon Battery at Pendennis Castle, dating from the Second World War

By the start of the 20th century, developments in guns and armour had made most of the Device Forts that remained in service too small to be useful. Modern weapons systems and their supporting logistics facilities such as munitions stores could not fit within the 16th-century designs.[231] A 1905 review of the Falmouth defences concluded that the naval artillery at St Mawes had become superfluous, as the necessary guns could be mounted at combination of Pendennis and newer sites along the coast, and the castle was disarmed.[232] A review in 1913 concluded that keeping naval artillery at Calshot was also unnecessary, and the site was turned into an experimental seaplane station instead.[233]

Meanwhile, concerns had been growing about the unsympathetic treatment of historic military buildings by the War Office; for its part, the War Office was concerned that it might find itself financially supporting these properties from its own budget.[234] Yarmouth Castle was passed to the Commissioners of Woods and Forests in 1901, with parts of it were leased to the neighbouring hotel.[235] The War Office concluded that Walmer and Deal had no remaining military value and agreed to transfer the castles to the Office of Works in 1904, who opened both former fortifications to visitors.[236] Portland Castle was placed onto what was known as the Schedule C list, which meant that the Army would continue to use and manage the historic property, but would receive advice on the suitability of repairs from the Office of Works.[237]

With the outbreak of the First World War, naval operations were mainly focused along the south-east and southern coasts.[238] The defences of Pendennis were reinforced, while Southsea, with the addition of anti-Zeppelin guns, formed part of the Fortress Portsmouth plan for defending the Solent.[239] Calshot formed a base for anti-submarine warfare, and the remaining castles of the Downs were used to support the activities of the Dover Patrol.[240] St Mawes and Portland were used as barracks, and Walmer became a weekend retreat for the Prime Minister, Asquith, exploiting its good communication links with the front line in France.[241]

During the Second World War, Britain's coastal defences depended on extensive barriers constructed along the shores, combined with large numbers of small defensive artillery positions supported by air cover.[242] Several of the Device Forts were brought back into service in this way. Pendennis, St Catherine's, St Mawes and Walmer were equipped with naval gun batteries, Calshot and Hurst were rearmed with naval guns and anti-aircraft defences, and Sandsfoot was used as an anti-aircraft battery.[243] Southsea continued in service, and was involved in Operation Grasp, which seized the French fleet in 1940.[244] Others were used as support facilities; Yarmouth was requisitioned for military use; Portland was used for accommodation, offices and as an ordnance store, and West Cowes used as a naval headquarters for part of the D-Day landings.[245] Camber was used as an early warning and decoy site to distract raids from nearby Rye.[246] Early in the war a German bomber destroyed much of the captain's quarters at Deal, forcing William Birdwood to move to Hampton Court Palace.[247] The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was appointed as the captain of Walmer Castle during the war, but declined to use it as a residence, noting that it was too expensive for him to maintain, and that it lay within the range of German artillery.[248]

1946–21st century

Sandgate Castle, damaged by coastal erosion and converted into a private house during the 1970s

After the war, coastal defences became increasingly irrelevant as nuclear weapons came to dominate the battlefield.[249] The remaining Device Forts still in military use were initially garrisoned with reservist units and then closed as military establishments.[250] St Catherine's and Portland were decommissioned in the late 1940s, Hurst, Pendennis and Yarmouth in the 1950s, Southsea in 1960 and, after, the closure of its air base, Calshot followed in 1961.[251]

Widespread restoration work was then carried out; at Calshot, Deal, Hurst, Pendennis, Portland, St Catherine's and Southsea, the more modern additions to the fortifications were destroyed in an attempt to recreate the appearance of the castles at earlier periods of their history, ranging from the 16th to the 19th centuries.[252] There was extensive research into the forts during this period, commencing in 1951 with a long-running research project commissioned by the Ministry of Works into the Device Forts, which in turn led to heightened academic interest in their histories during the 1980s.[253]

A range of the fortifications were opened to the public in the post-war years.[254] Deal, Hurst, Pendennis and Portland opened in the 1950s, and Southsea in 1967.[255] Calshot followed in the 1980s, Camber after a long period of restoration work in 1994, and Sandsfoot reopened following repair work in 2012.[256] Visitor numbers vary across the sites; Southsea Castle, for example, received over 90,000 visitors in 2011–12.[257] Other forts were put to different uses: Netley was first used a nursing home, and then converted into private flats; Brownsea became a corporate hotel for the employees of the John Lewis Partnership; and Sandgate was restored in the 1970s to form a private home.[258]

By the 21st century many of the Device Forts had been damaged by, or in some cases lost entirely, to coastal erosion; the problem had existed at some locations since the 16th century and still persists, for example at Hurst.[259] East Cowes Castle and East Tilbury Fort have been entirely lost, while the East Blockhouse, Mersea and Sandsfoot have been badly damaged, a third of Sandgate and most of St Andrews have been washed away.[260] Other sites were demolished, built upon or simply eroded over time; almost no trace remains of the bulwarks along the Downs, for example.[261] The remaining sites are protected by UK conservation law, either as scheduled monuments or listed buildings.[262]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Device Forts. |

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

Notes

^ In the 16th century, a variety of contemporary terms were used, often interchangeably, to describe these fortifications, including "blockhouses", "bulwarks", "castles" and "fortresses". Modern historians have also used different terms to describe and analyse the fortifications: B. Morley, for example, distinguishes between the "Henrician castles", the larger fortifications such as Walmer, Deal or Hull, and the "Henrician blockhouses", such as Tilbury or Gravesend; Peter Harrington similarly distinguishes between the "castles/forts" and "blockhouses"; Andrew Saunders separate out between the "castles", "forts" and "blockhouses", and stresses the breadth of the Device programme across England and Wales.[1]

^ abcdef Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. The £376,000 total cost of the Device Forts in 1547 might be equivalent, in 2015 terms, to between £1,949 million, using the UK earning index, and £82,120 million, using a share of GDP measure. A castle costing £5,000 could equate to between £25.92 million and £1,092 million. Richard Lee's salary of £30 a year could equate, in 2015 terms, to between £15,770, using the UK RPI measure, and £155,500, using the UK earning index. A labourer's wage of five pence a day could equate to between £26 and £259.[2]

^ In this map of the Thames, south is depicted to the top of the map, contrary to usual cartographic practice; west is therefore on the right hand side of the map, and east to the left.

^ In the 16th century, stone masons, bricklayers carpenters worked with stone, bricks and wood; carters moved material; lime burners produced an important raw material for mortar; sawyers cut wood; plumbers worked on the lead used in roofing; scavelmen and dikers on waterways, ditches and earth banks.

^ Steam power enabled enemy vessels to cross the Channel much faster, while sailing ships that had been only able to pass river defences slowly when moving against the tide, making them vulnerable to their guns, were now replaced by steam ships that threatened to cruise past them at speed.[213]

^ The authorities were concerned that modern artillery shells striking the stone walls of Calshot's keep would create large numbers of stone splinters, incapacitating the gun crews.[215]

References

^ Morley 1976, pp. 8–9; Harrington 2007, pp. 3, 8; Saunders 1989, pp. 37, 40

^ Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 10 October 2015.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Morley 1976, pp. 8–9

^ Harrington 2007, pp. 9–11; Saunders 1989, pp. 34–36

^ Colvin 1968, p. 225; King 1991, pp. 168–9

^ Johnson 2002, pp. 178–180; more needed.

^ Thompson 1987, pp. 103–111; Pounds 1994, pp. 256–257

^ Colvin 1968, p. 225; Pounds 1994, p. 249

^ Biddle et al. 2001, pp. 11, 21, 333; Walton 2010, p. 69

^ King 1991, pp. 176–177

^ Morley 1976, p. 7; Harrington 2007, p. 5

^ ab Thompson 1987, p. 111; Hale 1983, p. 63

^ Hale 1983, p. 63

^ Morley 1976, p. 7

^ Hale 1983, p. 63; Harrington 2007, p. 5

^ Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, pp. 63–64

^ Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, p. 66; Harrington 2007, p. 6

^ Coad 2000, p. 26; "Design for Henrician castle on the Kent coast", British Library, retrieved 29 June 2016

^ Harrington 2007, p. 6; King 1991, pp. 177–178

^ ab Harrington 2007, p. 11 Walton 2010, p. 70

^ Harrington 2007, p. 12

^ Harrington 2007, p. 20

^ King 1991, p. 178; Harrington 2007, p. 16

^ Harrington 2007, p. 16

^ Harris 1980, pp. 54–55; Rutton 1893, p. 229

^ King 1991, p. 178

^ Harrington 2007, p. 20; Smith 1980, p. 342; Saunders 1989, p. 42

^ Harrington 2007, p. 21; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 1; Saunders 1989, p. 41; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 470

^ Jenkins 2007, p. 153; Harrington 2007, pp. 8, 28; Morley 1976, pp. 8–9

^ Harrington 2007, p. 22; Saunders 1989, p. 41; Crane 2012, p. 2

^ Harrington 2007, p. 11

^ Jenkins 2007, p. 153; Harrington 2007, p. 24

^ Morley 1976, pp. 8–9; Harrington 2007, p. 25; Pettifer 2002, p. 86

^ Harrington 2007, p. 29; King 1991, p. 177; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 472

^ Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 470–471

^ "St Andrew's Castle", Historic England, retrieved 2 August 2015; Kenyon 1979, p. 75

^ Lowry 2006, p. 9

^ Harrington 2007, p. 29; Lowry 2006, p. 10

^ ab Hale 1983, pp. 79–80

^ Hale 1983, p. 80

^ Harrington 2007, pp. 29–30

^ Harrington 2007, p. 30

^ Saunders 1989, p. 51; "Fort Victoria", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015

^ Potter 2011, p. 376; Hale 1983, p. 86; Harrington 2007, p. 45

^ Potter 2011, p. 376

^ Harrington 2007, p. 46

^ Hale 1983, p. 86

^ Biddle et al. 2001, pp. 33, 35; Harrington 2007, pp. 46–47

^ Harrington 2007, pp. 46–47

^ ab Hale 1983, p. 70

^ abc Saunders 1989, p. 45

^ Walton 2010, pp. 68, 71; Harrington 2007, pp. 15–15

^ Saunders 1989, p. 45; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 11; Jonathan Hughes (2008), "Benese, Richard (d. 1547)" (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 30 July 2016

^ Walton 2010, p. 70

^ Corney 1968, p. 7; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 561–562

^ Walton 2010, p. 68

^ Skempton 2002, p. 303; Saunders 1989, pp. 44–45; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 31

^ Walton 2010, pp. 67–68; Saunders 1989, p. 45

^ King 1991, p. 175; Harrington 2007, p. 11; Marcus Merriman (2004), "Lee, Sir Richard (1501/2–1575)", Oxford University Press, retrieved 30 July 2016

^ ab Creighton 2002, p. 51; Brown 1989, pp. 70–71

^ Morley 1976, p. 15

^ King 1991, pp. 175–176

^ King 1991, p. 180; Saunders 1989, p. 37

^ Saunders 1989, p. 40

^ King 1991, p. 178; Saunders 1989, pp. 37–28

^ Thompson 1987, p. 112; Saunders 1989, pp. 44–45

^ Thompson 1987, p. 112

^ Saunders 1989, pp. 37–39, 43–44; Lowry 2006, p. 13; Morley 1976, p. 22

^ King 1991, p. 180; Morley 1976, p. 23

^ ab Lowry 2006, p. 10

^ Morley 1976, pp. 22–24

^ King 1991, p. 179

^ Smith 1980, pp. 349, 357–358; Smith 1974, p. 143

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12; Kenyon 1979, pp. 61–62

^ Thompson 1987, p. 113; Harrington 2007, p. 52

^ Harrington 2007, p. 52; Lowry 2006, p. 13; Saunders 1989, pp. 43–44

^ Harrington 2007, p. 52

^ Hale 1983, pp. 89–90

^ Thompson 1987, p. 113; Hale 1983, pp. 77, 90

^ ab Saunders 1989, p. 51

^ Saunders 1989, p. 51; Hale 1983, pp. 77, 90

^ Rigold 2012, p. 4

^ ab Morley 1976, p. 26; Saunders 1989, p. 46

^ Harrington 2007, p. 8; Skempton 2002, p. 582

^ Saunders 1989, p. 46

^ Leland 1907, pp. 202–203; Chandler 1996, p. 43; "Devils Point Artillery Tower", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015

^ Saunders 1989, p. 46; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 28; Skempton 2002, p. 582

^ Saunders 1989, p. 46; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 28; Harrington 2007, p. 18

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 28; Hale 1983, p. 70

^ Harrington 2007, p. 8; Hale 1983, p. 70

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 26; Saunders 1989, p. 46; Smith 1974, p. 144

^ Morley 1976, p. 29

^ Hale 1983, p. 71

^ Harrington 2007, p. 8

^ Pettifer 2002, p. 86; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 17 May 2015; "East Cowes Castle", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 26 June 2015; Hale 1983, p. 71; Saunders 1989, p. 46

^ Smith 1980, p. 344; "Milton Chantry", Historic England, retrieved 13 May 2015

^ ab Harrington 2007, pp. 37–38

^ Biddle et al. 2001, pp. 1, 35; Saunders 1960, p. 154; Saunders 1977, p. 9; Pattison 2004, p. 21; Elvin 1890, p. 162

^ Harrington 2007, pp. 38–39; Morley 1976, p. 26

^ Harrington 2007, p. 38

^ Harrington 2007, p. 37; Saunders 1989, p. 47

^ Morley 1976, p. 26; Harrington 2007, p. 39; Saunders 1989, p. 47

^ Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 16

^ Morley 1976, p. 26; Saunders 1989, p. 47

^ abc Saunders 1989, p. 47

^ Symonds 1914, pp. 32–33; Norrey 1988, p. 794; Saunders 1989, p. 51; Harrington 2007, p. 33; Sydenham 1839, pp. 387, 390

^ abc Harrington 2007, p. 41

^ Coad 1990, p. 20; Kenyon 1979, p. 72; Coad 2013, p. 11; Lawson 2002, p. 8

^ Smith 1980, p. 344; Saunders 1989, p. 51; Harrington 2007, p. 33; Sydenham 1839, pp. 387, 390

^ ab Saunders 1989, p. 47; Kenyon 1979, p. 76

^ Biddle et al. 2001, pp. 44–46

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 46

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 46; Hammer 2003, p. 79

^ Lowry 2006, p. 10; Morley 1976, pp. 21–23

^ Lowry 2006, p. 10; Morley 1976, pp. 21–23; Hammer 2003, p. 79

^ Hammer 2003, p. 79

^ ab "Henry's Gun", Hull City Council, retrieved 4 June 2016

^ Harrington 2007, p. 42

^ Lowry 2006, p. 10; Harrington 2007, p. 41; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 345

^ "A Colored Bird's Eye View of "A Castle for the Downes;" Probably an Early Design for Walmer and Sundown Castles", British Library, retrieved 24 August 2016

^ Coad 2006, p. 103; Harrington 2007, p. 47

^ Harrington 2007, p. 47

^ "East Cowes Castle", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, pp. 457, 459, 462, 464–465

^ ab Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 471

^ Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 16; Hirst 1895, p. 30; K. J. Alison (1969), "Fortifications", British History Online, retrieved 12 June 2016

^ Smith 1980, p. 347

^ ab Biddle et al. 2001, p. 40; Pattison 2009, pp. 34–35

^ Pattison 2009, p. 35; Coad 2013, p. 11; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 35; Lawson 2002, p. 22

^ Coad 2000, pp. 28–29; Elvin 1894, pp. 78–81; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 471

^ Saunders 1960, pp. 155–156; Pattison 2004, p. 20

^ Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 471; Howes & Foreman 1999, p. 18; Crane 2012, p. 2; Smith 1974, p. 151

^ Harrington 2007, p. 48

^ Coad 2000, pp. 28–29; Elvin 1894, pp. 78–81

^ Pattison 2009, pp. 35, 38

^ Pattison 2009, p. 38; Harrington 2007, p. 48

^ Coad 2006, p. 103

^ Pattison 2009, p. 38; Saunders 1989, p. 69

^ Pattison 2009, p. 38; Harrington 2007, p. 49

^ O'Neill 1985, p. 6; Saunders 1989, p. 69; Rutton 1895, pp. 249–250; Smith 1974, pp. 152–53

^ Coad 1990, p. 20

^ Pattison 2009, p. 38; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 10

^ "Fort Victoria", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; Biddle et al. 2001, pp. 35, 41

^ Bull 2008, pp. xxi–xxii; Coad 2006, p. 103

^ Gaunt 2014, p. 88

^ Smith 1974, pp. 153–154

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 42; Rutton 1895, pp. 250–251; Elvin 1894, p. 131; Elvin 1890, p. 183;

^ Wedgwood 1970, pp. 98–99

^ Sydenham 1839, p. 391; Van Raalte 1905, p. 190; Godwin 1904, p. 6

^ William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 15; "The Castle", Royal Yacht Squadron, archived from the original on 6 April 2015, retrieved 26 June 2015; Godwin 1904, pp. 26–27

^ Corney 1968, p. 14; Brooks 1996, p. 10; Harrington 2007, p. 50

^ "St Andrew's Castle", Historic England, retrieved 17 May 2015; Michael Heaton, "Netley Castle, Hampshire", Michael Heaton Heritage Consultants, archived from the original on 25 September 2006, retrieved 18 August 2015

^ Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 27–28

^ Davison 2000, p. 29

^ Harrington 2007, pp. 49–50; Lawson 2002, pp. 19, 24; Harrington 2007, p. 49; Barrett 1910, pp. 206–207

^ Barrett 1910, pp. 208–209; Lawson 2002, p. 24

^ Pattison 2009, p. 39

^ Pattison 2009, p. 39; Jenkins 2007, p. 156; Mackenzie 1896, p. 13; Oliver 1875, pp. 93–94

^ Department of the Environment 1975, p. 11; Pattison 2009, pp. 39–40

^ Pattison 2009, p. 40; Department of the Environment 1975, p. 12

^ Department of the Environment 1975, p. 12; Lawson 2002, pp. 19, 24; Harrington 2007, p. 49

^ Harrington 2007, p. 50; Kennedy 1962, pp. 251–252

^ Kennedy 1962, pp. 251–252

^ Rutton 1895, p. 250

^ Ashton 1994, pp. 439–440

^ ab "The Tudor Fort at East Mersea", Mersea Museum, archived from the original on 6 April 2016, retrieved 6 April 2016

^ Ashton 1994, p. 440; Harrington 2007, p. 51

^ ab Harrington 2007, p. 51

^ Harrington 2007, p. 51; Ashton 1994, p. 442; O'Neill 1985, p. 7

^ Coad 2000, p. 31

^ O'Neill 1985, p. 7; Coad 2000, p. 31

^ Harrington 2007, p. 51; Ashton 1994, p. 442

^ abc Harrington 2007, p. 53

^ William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 15 Elvin 1894, p. 118; Webb 1977, pp. 18–19; Michael Heaton, "Netley Castle, Hampshire", Michael Heaton Heritage Consultants, archived from the original on 25 September 2006, retrieved 18 August 2015; Webb 1977, pp. 18–19; Lawson 2002, p. 24; Elvin 1890, pp. 211–213

^ "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 26 June 2015; "Cowes Castle", Royal Yacht Squadron, archived from the original on 6 April 2015, retrieved 26 June 2015; "The Tudor Fort at East Mersea", Mersea Museum, archived from the original on 6 April 2016, retrieved 6 April 2016; Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 42, 44; Webb 1977, pp. 18–19; Lawson 2002, p. 24

^ Elvin 1894, pp. 118, 131; Coad 2000, p. 32; O'Neill 1985, p. 10

^ Lawson 2002, p. 24

^ "Little Dennis Blockhouse", Historic England, retrieved 10 May 2015; "The Tudor Fort at East Mersea", Mersea Museum, archived from the original on 6 April 2016, retrieved 6 April 2016; Garnett 2005, p. 7; Van Raalte 1905, p. 190

^ O'Neill 1985, p. 11; Coad 2000, p. 32; Elvin 1894, pp. 123–25

^ Tomlinson 1973, p. 6

^ O'Neill 1985, p. 11; Coad 2000, p. 32; Elvin 1894, pp. 123–25; William Page (1912), "Parishes: Hordle", British History Online, retrieved 7 February 2016; Coad 1990, p. 21; Rutton 1895, p. 248; Lawson 2002, p. 22

^ Symonds 1914, pp. 32–33; Norrey 1988, p. 474; Michael Heaton, "Netley Castle, Hampshire", Michael Heaton Heritage Consultants, archived from the original on 25 September 2006, retrieved 18 August 2015

^ Smith 1974, pp. 154–155; Saunders 1989, pp. 84–85

^ Saunders 1989, pp. 85–87

^ Pattison 2009, p. 40; Saunders 1960, p. 163; Saunders 1977, pp. 11–13; Corney 1968, p. 15; Saunders 1989, p. 91; Moore 1990, p. 7; William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 16

^ Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 56, 59; Saunders 1989, pp. 100–101

^ Elvin 1894, p. 126; O'Neill 1985, p. 12

^ Childs 1980, pp. 151, 193; Miller 2007, p. 241

^ William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 16

^ Garnett 2005, p. 7; Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) (1970), "Studland", British History Online, retrieved 13 July 2015; "West Cowes Castle", Historic England, retrieved 26 June 2015

^ ab Coad 2000, pp. 32–33; Coad 2008, p. 29; J. K. Laughton (2008), "Norris, Sir John (1670/71–1749)" (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 29 June 2016

^ Corney 1968, p. 17; Brooks 1996, p. 12

^ Pattison 2009, p. 41; Lawson 2002, pp. 25, 27; Saunders 1989, pp. 115–116

^ Saunders 1989, p. 122

^ "The Tudor Fort at East Mersea", Mersea Museum, archived from the original on 6 April 2016, retrieved 6 April 2016; A. Baggs; Beryl Board; Philip Crummy; Claude Dove; Shirley Durgan; N. Goose; R. Pugh; Pamela Studd; C. Thornton (1994), Janet Cooper; C. Elrington, eds., "Fishery", A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9, the Borough of Colchester, British History Online, pp. 264–269, retrieved 7 April 2016; "East Tilbury Blockhouse", Historic England, retrieved 3 September 2016

^ Pattison 2009, pp. 42–43; Coad 2006, p. 105; Coad 2013, p. 14

^ Harrington 2007, p. 54; Morley 1976, p. 41

^ Coad 2006, p. 103; Pattison 2009, pp. 42–43

^ Coad 1985, pp. 67–68; Coad 1990, p. 23; Pattison 2009, p. 42

^ Harris 1980, pp. 73–82; Sutcliffe 1973, p. 55

^ "The Tudor Fort at East Mersea", Mersea Museum, archived from the original on 6 April 2016, retrieved 6 April 2016; Saunders 1960, p. 166; Pattison 2004, p. 27; Elvin 1890, p. 226; Elvin 1894, p. 138; Coad 2000, p. 34

^ Corney 1968, p. 18; Howes & Foreman 1999, pp. 166, 169; Coad 2013, p. 14; "Hull Castle, South Blockhouse and Part of Late 17th century Hull Citadel Fort at Garrison Side", Historic England, retrieved 12 June 2016

^ Elvin 1890, pp. 246, 248–249; Coad 2006, p. 106; Maurice-Jones 2012, p. 102

^ Elvin 1890, pp. 248–249

^ Elvin 1890, pp. 246, 248

^ Coad 2006, p. 106

^ Maurice-Jones 2012, p. 102

^ Harrington 2007, p. 54

^ Coad 2013, p. 17Coad 2006, pp. 106–107; Elvin 1890, p. 226; Elvin 1894, p. 188

^ Lawson 2002, pp. 27–28, 30; Warner 1795, p. 67; Anonymous 1824, p. 137

^ Anonymous 1883, pp. 37–38; Smith 1974, pp. 158–161; "Gravesend Blockhouse", Historic England, retrieved 16 May 2015

^ Guillame 1848, p. 4; Pevsner & Lloyd 1967, pp. 348–350

^ Coad 1985, p. 76; Pattison 2009, p. 43

^ R. S. J. Martin and A. H. Flatt (2007), "Golden Hill Fort, Freshwater, Isle of Wight" (PDF), Golden Hill Fort, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2016, retrieved 17 January 2016

^ Brooks 1996, p. 16; Corney 1968, p. 19; Coad 1990, p. 26; Coad 1985, p. 77; Pattison 2009, p. 43; Jenkins 2007, p. 158; Pattison 2009, p. 44

^ ab Coad 2006, pp. 106–107

^ "History of St Catherine's Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 14 June 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015

^ "History of St Catherine's Castle", England Heritage, retrieved 26 May 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015

^ "West Blockhouse, Dale", Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, retrieved 10 May 2015; Cadw, "West Blockhouse Fort, Dale", www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk, British Listed Buildings, retrieved 16 July 2016

^ Brooks 1996, p. 16

^ Harris 1980, pp. 82, 86; Brooks 1996, p. 16; Corney 1968, pp. 19, 21

^ Coad 1990, pp. 26–27; Coad 1985, pp. 85–87

^ Saunders 1960, p. 172

^ Lawson 2002, p. 30; Pettifer 2002, p. 66

^ Jenkins 2007, p. 159; Pattison 2009, p. 44; Coad 1985, pp. 96–97; Coad 1990, p. 28

^ Jenkins 2007, p. 159; Pattison 2009, p. 44

^ Coad 1985, pp. 97–98 Coad 1990, p. 28

^ Coad 2006, pp. 109–110

^ Coad 2006, pp. 103–104, 109–110; Brooks 1996, p. 16; Corney 1968, pp. 19, 21; Coad 2013, p. 18

^ "Cowes Castle", Royal Yacht Squadron, archived from the original on 6 April 2015, retrieved 26 June 2015

^ Rigold 2012, p. 19; Colvin, Ransome & Summerson 1982, p. 475; Rutton 1893, p. 253; Lewis 1884, p. 178; William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 19

^ Coad 2006, pp. 103–104

^ Jenkins 2007, p. 161

^ Coad 2013, pp. 20–22

^ Fry 2014, pp. 10–14

^ William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Hopkins 2004, p. 7; Rigold 2012, p. 19

^ Fry 2014, pp. 11–12, 15–16; Coad 2000, p. 35

^ Fry 2014, pp. 13–14

^ Davison 2000, p. 34

^ Brooks 1996, p. 17; Pattison 2009, p. 47; Osborne 2011, p. 127

^ Coad 2013, pp. 20–22; Harrington 2007, p. 55

^ Coad 2008, p. 35; Jenkins 2002, p. 295; Mulvagh 2008, p. 320; Lawson 2002, p. 30; Jenkins 2007, p. 161

^ Morley 1976, p. 41

^ "History of St Catherine's Castle", England Heritage, retrieved 26 May 2015; "St Catherine's Castle Coastal Battery", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; Jenkins 2007, p. 162; Coad 2013, p. 22; "Sandsfoot Castle", Historic England, retrieved 27 December 2015; "Deal Emergency Coastal Battery", Historic England, retrieved 26 June 2016; Pattison 2009, p. 48; Coad 1985, pp. 100–101; Coad 1990, p. 29

^ Corney 1968, p. 22; Murfett 2009, p. 84

^ Finley 1994, p. 1; Rigold 2012, p. 19; "Operation Neptune" (PDF), NHB, pp. 7–8, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2015, retrieved 26 June 2015; Lawson 2002, pp. 30–32; "Monument No. 1413734", Historic England, retrieved 31 August 2015

^ Biddle et al. 2001, p. 133; "Camber Castle", Heritage Gateway, retrieved 9 April 2015; "Camber Castle", Historic England, retrieved 9 April 2015

^ Coad 2000, p. 34; Parker 2005, p. 104

^ Coad 2008, p. 29; Churchill 1948, p. 737

^ Saunders 1989, p. 225

^ Harrington 2007, p. 55

^ "History of St Catherine's Castle", England Heritage, retrieved 26 May 2015; "St Catherine's Castle Coastal Battery", Historic England, retrieved 26 May 2015; Coad 2013, p. 24; Pattison 2009, p. 48; Rigold 2012, p. 19; Corney 1968, p. 22; Brooks 1996, p. 20; Coad 1990, p. 29; Lawson 2002, pp. 3, 32; Chapple 2014, p. 84

^ Corney 1968, p. 22; Brooks 1996, p. 20; Coad 2000, p. 34; "Deal Castle", Hansard, 1 May 1956, retrieved 26 June 2016; Coad 2013, p. 24; Coad 2006, p. 112; "Calshot Castle", Historic England, retrieved 10 October 2015; "History of St Catherine's Castle", England Heritage, retrieved 26 May 2015; Coad 1990, p. 11; "Pendennis Castle" (PDF), English Heritage, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2015, retrieved 27 November 2015; Lawson 2002, pp. 4, 32

^ King 1991, p. 175; Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12

^ King 1991, p. 175

^ Corney 1968, p. 22; Brooks 1996, p. 20; Lawson 2002, pp. 3, 32; Chapple 2014, p. 84; Pattison 2009, p. 48; Coad 2000, p. 34; Coad 1990, p. 29