Turkish War of Independence

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (October 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Turkish War of Independence (Turkish: Kurtuluş Savaşı "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as İstiklâl Harbi "Independence War" or Millî Mücadele "National Campaign"; 19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was fought between the Turkish National Movement and the proxies of the Allies – namely Greece on the Western front, Armenia on the Eastern, France on the Southern and with them, the United Kingdom and Italy in Constantinople (now Istanbul) – after parts of the Ottoman Empire were occupied and partitioned following the Ottomans' defeat in World War I.[43][44][45] Few of the occupying British, French, and Italian troops had been deployed or engaged in combat.

The Turkish National Movement (Kuva-yi Milliye) in Anatolia culminated in the formation of a new Grand National Assembly (GNA; Turkish: BMM) by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his colleagues. After the end of the Turkish–Armenian, Franco-Turkish, Greco-Turkish fronts (often referred to as the Eastern Front, the Southern Front, and the Western Front of the war, respectively), the Treaty of Sèvres was abandoned and the Treaties of Kars (October 1921) and Lausanne (July 1923) were signed. The Allies left Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey decided on the establishment of a Republic in Turkey, which was declared on 29 October 1923.

With the establishment of the Turkish National Movement, the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, and the abolition of the sultanate, the Ottoman era and the Empire came to an end, and with Atatürk's reforms, the Turks created the modern, secular nation-state of Turkey on the political front. On 3 March 1924, the Ottoman caliphate was officially abolished and the last Caliph was exiled.

Contents

1 30 October 1918 – May 1919

2 Initial organization

2.1 Decoding national movement

2.2 Representational problem

2.3 Last Ottoman Parliament

2.4 Shift from de facto to de jure occupation

3 Jurisdictional conflict

3.1 Dissolution of the Ottoman parliament

3.2 Promulgation of the Grand National Assembly

3.3 Early pressure on nationalist militias

3.4 Establishment of the army

3.5 Conflicts

3.5.1 East

3.5.1.1 Eastern resolution

3.5.2 West

3.5.2.1 Western active stage

3.5.2.2 Western resolution

3.5.3 South

3.6 Conference of London

4 Stage for peace

4.1 Armistice of Mudanya

4.2 Abolition of the sultanate

4.3 Conference of Lausanne

4.4 Treaty of Lausanne

4.5 Establishment of the Republic

5 See also

6 Footnotes

7 References

8 External links

9 Bibliography

30 October 1918 – May 1919

Play media

Play mediaAllied occupation of Constantinople

Greek troops marching on Izmir's coastal street, May 1919.

On 30 October 1918, the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I, bringing hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I to a close. The treaty granted the Allies the right to occupy forts controlling the Straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus; and the right to occupy "in case of disorder" any territory in case of a threat to security.[46][47]Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe—the British signatory of the Mudros Armistice—stated the Triple Entente′s public position that they had no intention to dismantle the government of the Ottoman Empire or place it under military occupation by "occupying Constantinople".[48] However, dismantling the Ottoman government and partitioning the Ottoman Empire among the Allied nations had been an objective of the Entente since the start of the war.[49]

On 13 November 1918, a French brigade entered the city to begin the Occupation of Constantinople and its immediate dependencies, followed by a fleet consisting of British, French, Italian and Greek ships deploying soldiers on the ground the next day. A wave of seizures took place in the following months by the Allies. On 14 November, joint Franco-Greek troops occupied the town of Uzunköprü in Eastern Thrace as well as the railway axis till the train station of Hadımköy near Çatalca on the outskirts of Constantinople. On 1 December, British troops based in Syria occupied Kilis. Beginning in December, French troops began successive seizures of Ottoman territory, including the towns of Antakya, Mersin, Tarsus, Ceyhan, Adana, Osmaniye and Islahiye.[50] The first bullet was fired by Mehmet Çavuş[note 3] in Dörtyol against the French on 19 December 1918.[51]

On 19 January 1919, the Paris Peace Conference opened, a meeting of Allied nations that set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers, including the Ottoman Empire.[52] As a special body of the Paris Conference, "The Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey" was established to pursue the secret treaties they had signed between 1915 and 1917.[53] Among the objectives was a new Hellenic Empire based on the Megali Idea. This was promised by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George to Greece.[54] Italy sought control over the southern part of Anatolia under the Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne. France expected to exercise control over Hatay, Lebanon and Syria, and also wanted control over a portion of southeastern Anatolia based on the Sykes-Picot Agreement. France signed the Franco-Armenian Agreement and promised the realization of an Armenian state in the Mediterranean region in exchange to the French Armenian Legion.[55]

Meanwhile, Allied countries continued to lay claim to portions of the quickly crumbling Ottoman Empire. British forces based in Syria occupied Maraş, Urfa and Birecik, while French forces embarked by gunboats and sent troops to the Black Sea ports of Zonguldak and Karadeniz Ereğli commanding Turkey's coal mining region. At the Paris Peace Conference, competing claims of Western Anatolia by Greek and Italian delegations led Greece to land the flagship of the Greek Navy at Smyrna, resulting in the Italian delegation walking out of the peace talks. On 30 April, Italy responded to the possible idea of Greek incorporation of Western Anatolia by also sending a warship to Smyrna (Izmir) as a show of force against the Greek campaign. A large Italian force also landed in Antalya. With the Italian delegation absent from the Paris Peace talks, Britain was able to sway France in favour of Greece and ultimately the Conference authorized the landing of Greek troops on Anatolian territory.

The Greek campaign of Western Anatolia began on 15 May 1919, as Greek troops began landing in Smyrna. For the city′s Muslim population, the day is marked by the "first bullet" fired by Hasan Tahsin[note 4] at the Greek standard bearer at the head of the troops, the murder by bayonet coups of Miralay Fethi Bey for refusing to shout "Zito Venizelos" and the killing and wounding of unarmed Turkish soldiers in the city's principal casern, as well as of 300-400 civilians. Greek troops moved from Smyrna outwards, to towns on the Karaburun peninsula, Selçuk, situated a hundred kilometers south of Smyrna at a key location that commands the fertile Menderes River valley and Menemen and Selçuk, towards the north and the southeast of Smyrna.

Initial organization

Play media

Play mediaAnatolia in 1919

Fahrî Yâver-i Hazret-i Şehriyâri ("Honorary Aide-de-camp to His Majesty Sultan") Mirliva Mustafa Kemal Paşa was assigned as the inspector of the 9th Army Troops Inspectorate to reorganize what remained of the Ottoman military units and to improve internal security on 30 April 1919.[56] According to Lord Kinross, through manipulation and the help of friends and sympathizers, Mustafa Kemal Paşa became the Inspector of virtually all of the Ottoman forces in Anatolia, tasked with overseeing the disbanding process of the remaining Ottoman forces.[57] He and his carefully selected staff left Constantinople aboard the old steamer SS Bandırma for Samsun on the evening of 16 May 1919.[58]

Resistance to Allied demands began at the very onset of the Ottoman Empire's defeat in World War I. Many Ottoman officials organized the secret Sentinel Association (Turkish: Karakol Cemiyeti) in reaction to the policies of the Allies. The objective of the Sentinel Association was to thwart Allied demands through passive and active resistance. Many Ottoman officials participated in efforts to conceal from the occupying authorities details of the burgeoning independence movement spreading throughout Anatolia. Munitions initially seized by the Allies were secretly smuggled out of Constantinople into Central Anatolia, along with Ottoman officers keen to resist any division of Ottoman territories. Mirliva Ali Fuad Paşa in the meantime had moved his XX Corps from Ereğli to Ankara and started organizing resistance groups, including Circassian immigrants under Çerkes Ethem.

Since the southern rim of Anatolia[where?] was effectively controlled by British warships and competing Greek and Italian troops, the Turkish National Movement′s headquarters moved to the rugged terrain of central Anatolia. The reasons for these new assignments is still a matter of debate; one view is that it was an intentional move to support the national movement, another was that the Sultan wanted to keep Constantinople under his control, a goal which was in total agreement with the aims of the occupation armies which could keep the Sultan under control. The most prominent idea given for the Sultan’s decision was by assigning these officers out of the capital, the Sultan was trying to minimize the effectiveness of these soldiers in the capital. The Sultan was cited as saying that without an organized army, the Allies could not be defeated, and the national movement had two army corps in May 1919,[citation needed] one was the XX Corps based in Ankara under the command of Ali Fuat Paşa and the other was XV Corps based in Erzurum under the command of Kâzım Karabekir Paşa.

Mustafa Kemal Paşa and his colleagues stepped ashore on 19 May and set up their first quarters in the Mintika Palace Hotel. Mustafa Kemal Paşa made the people of Samsun aware of the Greek and Italian landings, staged mass meetings (while remaining discreet) and made, thanks to the excellent telegraph network, fast connections with the army units in Anatolia and began to form links with various nationalist groups. He sent telegrams of protest to foreign embassies and the War Ministry about British reinforcements in the area and about British aid to Greek brigand gangs. After a week in Samsun, Mustafa Kemal Paşa and his staff moved to Havza, about 85 km (53 mi) inland.

Mustafa Kemal Paşa writes in his memoir[citation needed] that he needed nationwide support. The importance of his position, and his status as the "Hero of Anafartalar" after the Gallipoli Campaign, and his title of Fahri Yaver-i Hazret-i Şehriyari ("Honorary Aide-de-camp to His Majesty Sultan") gave him some credentials. On the other hand, this was not enough to inspire everyone. While officially occupied with the disarming of the army, he had increased his various contacts in order to build his movement's momentum. He met with Rauf Bey (Orbay), Ali Fuat Paşa (Cebesoy), and Refet Bey (Bele) on 21 June 1919 and declared the Amasya Circular (22 June 1919).

Decoding national movement

On 23 June, High Commissioner Admiral Calthorpe, realizing the significance of Mustafa Kemal′s discreet activities in Anatolia, sent a report about Mustafa Kemal to the Foreign Office. His remarks were downplayed by George Kidson of the Eastern Department. Captain Hurst (British army) in Samsun warned Admiral Calthorpe one more time, but Hurst′s units were replaced with a Brigade of Gurkhas. The movement of British units alarmed the population of the region and convinced the population that Mustafa Kemal was right[citation needed]. Right after this "The Association for Defense of National Rights" (Müdafaa-i Hukuk Cemiyeti) was founded in Trabzon, and a parallel association in Samsun was also founded, which declared that the Black Sea region was not safe. The same activities that happened in Smyrna were happening in the region. When the British landed in Alexandretta, Admiral Calthorpe resigned on the basis that this was against the Armistice that he had signed and was assigned to another position on 5 August 1919.[59]

On 2 July, Mustafa Kemal Pasha received a telegram from the Sultan. The Sultan asked him to cease his activities in Anatolia and return to the capital. Mustafa Kemal was in Erzincan and did not want to return to Constantinople, concerned that the foreign authorities might have designs for him beyond the Sultan's plans. He felt the best course for him was to take a two-month leave of absence.

The Representative committee was established at the Sivas Congress (4–11 September 1919).

Representational problem

On 16 October 1919, Ali Riza Pasha sent a navy minister, Hulusi Salih Pasha, to negotiate with the Turkish National Movement. Hulusi Salih Pasha was not part of World War I. Salih Pasha and Mustafa Kemal met in Amasya. Mustafa Kemal put the representational problems of Ottoman Parliament on the agenda. He wanted to have a signed protocol between Ali Rıza Pasha and the "representative committee." On the advice of the British, Ali Riza Pasha rejected any form of recognition or legitimacy claims by this unconstitutional political formation in Anatolia.

In December 1919, fresh elections were held for the Ottoman parliament. This was an attempt to build a better representative structure. The Ottoman parliament was seen as a way to reassert the central government′s claims of legitimacy in response to the emerging nationalist movement in Anatolia. In the meantime, groups of Ottoman Greeks had formed Greek nationalist militias within Ottoman borders and were acting on their own. Greek members of the Ottoman parliament repeatedly blocked any progress in the parliament, and most Greek subjects of the Sultan boycotted the new elections.

The elections were held and a new parliament of the Ottoman State was formed under the occupation. However, Ali Rıza Pasha was too hasty in thinking that his parliament could bring him legitimacy. The house of the parliament was under the shadow of the British battalion stationed at Constantinople. Any decisions by the parliament had to have the signatures of both Ali Rıza Pasha and the commanding British Officer. The freedom of the new government was limited. It did not take too long for the members of parliament to recognize that any kind of integrity was not possible in this situation. Ali Rıza Pasha and his government had become the voice of the Triple Entente. The only laws that passed were those acceptable to, or specifically ordered by the British.

Last Ottoman Parliament

The Turkish Army's entry into Izmir (known as the Liberation of Izmir) on 9 September 1922, following the successful Great Smyrna Offensive, effectively sealed the Turkish victory and ended the war. Izmir was the location where Turkish civilian armed resistance against the occupation of Anatolia by the Allies first began on 15 May 1919.

On 12 January 1920, the last Ottoman Chamber of Deputies met in the capital. First the Sultan's speech was presented and then a telegram from Mustafa Kemal, manifesting the claim that the rightful government of Turkey[citation needed] being in Ankara in the name of the Representative Committee.

A group called Felâh-i Vatan among the Ottoman parliament worked to acknowledge the decisions taken at the Erzurum Congress and the Sivas Congress. The British began to sense that a Turkish Nationalist movement had been flourishing, a movement with goals against English interests. The Ottoman government was not doing all that it could to suppress the nationalists. On 28 January the deputies met secretly. Proposals were made to elect Mustafa Kemal president of the Chamber, but this was deferred in the certain knowledge that the British would prorogue the Chamber[clarification needed] before it could do what had been planned all along, namely accept the declaration of the Sivas Congress.

On 28 January, the Ottoman parliament developed the National Pact (Misak-i Milli) and published it on 12 February. This pact adopted six principles, which called for self-determination, the security of Constantinople, and the opening of the Straits, also the abolition of the capitulations. In effect the Misak-i Milli solidified a lot of nationalist notions, which were in conflict with the Allied plans.[citation needed]

Shift from de facto to de jure occupation

The National Movement—which persuaded the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies to declare a "National Pact" (Misak-i Milli) against the occupying Allies–prompted the British government to take action. To put an end to Turkish Nationalist hopes, the British decided to systematically bring Turkey under their control. The plan was to dismantle Turkish Government organizations, beginning in Istanbul and moving deep into Anatolia. Mustafa Kemal's National Movement was seen as the main problem. The British Foreign Office was asked to devise a plan. The Foreign Office suggested the same plan previously used during the Arab Revolt. This time however, resources were channeled to warlords like Ahmet Anzavur. The politics of this decision were legitimised via the Treaty of Sèvres. Anatolia was to be westernized under Christian governments. That was the only way that Christians could be safe, said the British government. The Treaty of Sèvres placed most of Anatolia under Christian control. This policy aimed to break down authority in Anatolia by separating the Sultan, its government, and pitting Christians (Greece and Republic of Armenia, Armenians of Cilicia) against Muslims. The details of these covert operations are summarized below, in the section under Jurisdictional Conflict.[citation needed]

On the night of 15 March, British troops began to occupy key buildings and arrest Turkish nationalists. It was a very messy operation. At the military music school there was resistance. At least ten students died but the official death toll is unknown even today. The British tried to capture the leadership of the movement. They secured the departments of the Minister of War and of the Chief of the General Staff, Fevzi Çakmak. Çakmak was an able and relatively conservative officer who was known as one of the army's oldest field commanders. He soon became one of the principal military leaders of the National Movement.[citation needed]

A part from a newspaper published on 18 March 1920 (The Gray River Argus, New Zealand)

Mustafa Kemal was ready for this move. He warned all the nationalist organizations that there would be misleading declarations from the capital. He warned that the only way to stop the British was to organize protests. He said "Today the Turkish nation is called to defend its capacity for civilization, its right to life and independence – its entire future". Mustafa Kemal was extensively familiar with the Arab Revolt and British involvement. He managed to stay one step ahead of the British Foreign Office. This—as well as his other abilities—gave Mustafa Kemal considerable authority among the revolutionaries.[citation needed]

On 18 March the Ottoman parliament sent a protest to the Allies. The document stated that it was unacceptable to arrest five of its members. But the damage had been done. It was end of the Ottoman political system. This show of force by the British had left the Sultan as sole controller of the Empire. But the Sultan depended on their power to keep what was left of the empire. He was now a puppet of the Allies.[citation needed]

Jurisdictional conflict

The new government—hoping to undermine the National Movement—passed a fatwa (legal opinion) from Şeyhülislam to qualify the Turkish revolutionaries as infidels, calling for the death of its leaders.[60] The fatwa stated that true believers should not go along with the nationalist (rebels) movement. Along with this religious decree, the government sentenced Mustafa Kemal and prominent nationalists to death in absentia. At the same time, the müfti of Ankara Rifat Börekçi in defense of the nationalist movement, issued a counteracting fatwa declaring that the capital was under the control of the Entente and the Ferit Pasha government.[61] In this text, the nationalist movement's goal was stated as freeing the sultanate and the caliphate from its enemies.

Dissolution of the Ottoman parliament

Mustafa Kemal expected the Allies neither to accept the Harbord report nor to respect his parliamentary immunity if he went to the Ottoman capital, hence he remained in Anatolia. Mustafa Kemal moved the Representative Committee′s capital from Erzurum to Ankara so that he could keep in touch with as many deputies as possible as they traveled to Constantinople to attend the parliament. He also started a newspaper, the Hakimiyet-i Milliye (National Sovereignty), to speak for the movement both in Turkey and the outside world (10 January 1920).

Mustafa Kemal declared that the only legal government of Turkey was the Representative Committee in Ankara and that all civilian and military officials were to obey it rather than the government in Constantinople. This argument gained very strong support, as by that time the Ottoman Parliament was fully under Allied control.

Promulgation of the Grand National Assembly

The strong measures taken against the nationalists by the Ottoman government created a distinct new phase. Mustafa Kemal sent a note to the governors and force commanders, asking them to implement the election of delegates to join the GNA, which would convene in Ankara. Mustafa Kemal appealed to the Islamic world, asking for help to make sure that everyone knew he was still fighting in the name of the sultan who was also the caliph. He stated he wanted to free the caliph from the Allies. Plans were made to organize a new government and parliament in Ankara, and then ask the sultan to accept its authority.

A flood of supporters moved to Ankara just ahead of the Allied dragnets. Included among them were Halide Edip, Adnan (Adıvar), İsmet (İnönü), Mustafa Kemal’s important allies in the Ministry of War, and Celaleddin Arif, the president of the Chamber of Deputies. Yunus Nadi (Abalıoğlu), the owner of Yeni Gün newspaper, journalist-author and deputy of Izmir, Halide Edip (Adıvar) met in Geyve on 31 March. Two intellectuals discussed the necessity that a news agency should be established to counter the allied occupation administration′s censure over the news. They chose Anadolu as the name. Mustafa Kemal, whom they meet in Ankara, immediately launched initiatives to herald the establishment of the Anadolu Agency.[62] Mustafa Kemal wanted to transmit news stories to the world. Kemal also stressed the importance of making the national struggle heard inside and outside of the country.[62] Celaleddin Arif's desertion of the capital was of great significance. Celaleddin Arif stated that the Ottoman Parliament had been dissolved illegally. The Armistice did not give Allies the power to dissolve the Ottoman Parliament and the Constitution of 1909 had also removed the Sultan's power to do so, to prevent what Abdülhamid did in 1879.

Some 100 members of the Ottoman Parliament were able to escape the Allied roundup and joined 190 deputies elected around the country by the national resistance group. Ismet Inonü joined as a deputy from Edirne. In March 1920, Turkish revolutionaries announced that the Turkish nation was establishing its own Parliament in Ankara under the name Grand National Assembly (GNA). The GNA assumed full governmental powers. On 23 April , the new Assembly gathered for the first time, making Mustafa Kemal its first president and Ismet Inönü chief of the General Staff. The new regime’s determination to revolt against the government in the capital and not the Sultan was quickly made evident. By 3 May 1920, a Turkish Provisional Government was also formed in Ankara.

Early pressure on nationalist militias

Play media

Play mediaKuvva-i Milliye.

Anatolia had many competing forces on its soil: British battalions, Ahmet Aznavur forces, and the Sultan's army. The Sultan gave 4,000 soldiers from his Kuva-i Inzibatiye (Caliphate Army) to resist against the nationalists. Then using money from the Allies, he raised another army, a force about 2,000 strong from non-Muslim inhabitants which were initially deployed in Iznik. The Sultan's government sent forces under the name of the caliphate army to the revolutionaries and aroused counterrevolutionary outbreaks.[63]

The British being skeptical of how formidable these insurgents were, decided to use irregular power to counteract this rebellion. The nationalist forces were distributed all around Turkey, so many small units were dispatched to face them. In Izmit there were two battalions of the British army. Their commanders were living on the Ottoman warship Yavuz. These units were to be used to rout the partisans under the command of Ali Fuat Cebesoy and Refet Bele.

On 13 April 1920, the first conflict occurred at Düzce as a direct consequence of the sheik ul-Islam′s fatwa. On 18 April 1920, the Düzce conflict was extended to Bolu; on 20 April 1920, it extended to Gerede. The movement engulfed an important part of northwestern Anatolia for about a month. The Ottoman government had accorded semi-official status to the "Kuva-i Inzibatiye" and Ahmet Anzavur held an important role in the uprising. Both sides faced each other in a pitched battle near Izmit on 14 June. Ahmet Aznavur′s forces and British units outnumbered the militias. Yet under heavy attack some of the Kuva-i Inzibatiye deserted and joined the opposing ranks. This revealed the Sultan did not have the unwavering support of his men. Meanwhile, the rest of these forces withdrew behind the British lines which held their position.

Execution of a Kemalist Turk by the British forces in Izmit. (1920)

The clash outside Izmit brought serious consequences. The British forces opened fire on the nationalists and bombed them from the air. This bombing forced a retreat but there was a panic in Constantinople. The British commander—General George Milne—asked for reinforcements. This led to a study to determine what would be required to defeat the Turkish nationalists. The report—signed by Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch—concluded that 27 divisions would be sufficient, but the British army did not have 27 divisions to spare. Also, a deployment of this size could have disastrous political consequences back home. World War I had just ended, and the British public would not support another lengthy and costly expedition.

The British accepted the fact that a nationalist movement could not be faced without deployment of consistent and well-trained forces. On 25 June, the forces originating from Kuva-i Inzibatiye were dismantled under British supervision. The official stance was that there was no use for them. The British realized that the best option to overcome these Turkish nationalists was to use a force that was battle-tested and fierce enough to fight the Turks on their own soil. The British had to look no further than Turkey′s neighbor: Greece.

Establishment of the army

Before the Amasya Circular (22 June 1919), Mustafa Kemal met with a Bolshevik delegation headed by Colonel Semyon Budyonny[citation needed]. The Bolsheviks wanted to annex the parts of the Caucasus, including the Democratic Republic of Armenia, which were formerly part of Tsarist Russia. They also saw a Turkish Republic as a buffer state or possibly a communist ally. Mustafa Kemal′s official response was "Such questions had to be postponed until Turkish independence was achieved." Having this support was important for the national movement.[64]

The first objective was the securing of arms from abroad. They obtained these primarily from Soviet Russia and from Italy and France. These arms—especially the Soviet weapons—allowed the Turks to organize an effective army. The Treaties of Moscow and Kars (1921) arranged the border between Turkey and the Soviet-controlled Transcaucasian republics, while Russia itself was in a state of civil war and preparing to establish the Soviet Union. In particular Nakhchivan and Batumi were ceded to the future USSR. In return the nationalists received support and gold. For the promised resources, the nationalists had to wait until the Battle of Sakarya (August–September 1921).

By providing financial and war materiel aid, the Bolsheviks aimed to heat up the war between the Allies and the Turkish nationalists in order to delay the participation of more Allied troops in the Russian Civil War.[65] At the same time the Bolsheviks attempted to export communist ideologies to Anatolia and moreover supported individuals (for example: Mustafa Suphi) who were pro-communism.[65]

According to Soviet documents, Soviet financial and war materiel support between 1920 and 1922 amounted to: 39,000 rifles, 327 machine guns, 54 cannon, 63 million rifle bullets, 147,000 shells, 2 patrol boats, 200.6 kg of gold ingots and 10.7[66] million Turkish lira (which accounted for a twentieth of the Turkish budget during the war).[66] Additionally the Soviets gave the Turkish nationalists 100,000 gold rubles to help build an orphanage and 20,000 lira to obtain printing house equipment and cinema equipment.[67]

Conflicts

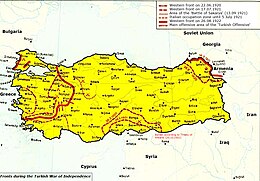

Map showing the Western, Eastern and Southern fronts during the Turkish War of Independence.

East

The border of the Republic of Armenia (ADR) and Ottoman Empire was defined in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (3 March 1918) after the Bolshevik revolution, and later by the Treaty of Batum (4 June 1918) with the ADR. It was obvious that after the Armistice of Mudros (30 October 1918) the eastern border was not going to stay as it was drawn. There were talks going on with the Armenian Diaspora and Triple Entente on reshaping the border. The Fourteen Points was seen as an incentive to the ADR, if the Armenians could prove that they were the majority of the population and that they had military control over the eastern regions. The Armenian movements on the borders were being used as an argument to redraw the border between the Ottoman Empire and the ADR. Woodrow Wilson agreed to transfer the territories back to the ADR on the principle that they were dominated by Armenians. The results of these talks were to be reflected on the Treaty of Sèvres (August 10, 1920). There was also a movement of Armenians from the southeast with French support. The Franco-Armenian Agreement granted the Armenian claims to Cilicia with the establishment of the French Armenian Legion. The general idea at that time was to integrate the ADR into the French supported southeast Armenian movement. This way the ADR could gain much-sought-after resources to balance the Bolshevik expansionist movements.

One of the most important fights had taken place on this border. The very early onset of a national army was proof of this, even though there was a pressing Greek danger to the west. The stage of the eastern campaign developed through Kâzim Karabekir's two reports (30 May and 4 June 1920) outlining the situation in the region. He was detailing the activities of the Armenian Republic and advising on how to shape the sources on the eastern borders, especially in Erzurum. The Russian government sent a message to settle not only the Armenian but also the Iranian border through diplomacy under Russian control. Soviet support was absolutely vital for the Turkish nationalist movement, as Turkey was underdeveloped and had no domestic armaments industry. Bakir Sami Bey was assigned to the talks. The Bolsheviks demanded that Van and Bitlis be transferred to Armenia. This was unacceptable to the Turkish revolutionaries.

Eastern resolution

The Treaty of Sèvres was signed by the Ottoman Empire and was followed by the occupation of Artvin by Georgian forces on 25 July.

The Treaty of Alexandropol (2 December 1920) was the first treaty signed by the Turkish revolutionaries. It nullified the Armenian activities on the eastern border, which was reflected in the Treaty of Sèvres as a succession of regions named Wilsonian Armenia. The 10th item in the Treaty of Alexandropol stated that Armenia renounced the Treaty of Sèvres, which stipulated Wilsonian Armenia.

After the peace agreement with the Turkish nationalists, in late November, a Soviet-backed Communist uprising took place in Armenia. On 28 November 1920, the 11th Red Army under the command of Anatoliy Gekker crossed over into Armenia from Soviet Azerbaijan. The second Soviet-Armenian war lasted only a week. After their defeat by the Turkish revolutionaries the Armenians were no longer a threat to the Nationalist cause. It is also possible to claim that had the ADR been content with the boundaries as of 1919, it could have shown more resistance to the Bolshevik conquest, both internally and externally, but that was not how things happened.

On 16 March 1921, the Bolsheviks and Turkey signed a more comprehensive agreement, the Treaty of Kars, which involved representatives of Soviet Armenia, Soviet Azerbaijan, and Soviet Georgia.

The arms left by the defeated ADR forces were sent to the west for use against the Greeks.

West

The war arose because the western Allies—particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George—had promised Greece territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire if Greece entered the war on the Allied side. These included parts of its ancestral homeland, Eastern Thrace, the islands of Imbros (Gökçeada), Tenedos (Bozcaada), and parts of Western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna (Izmir). Greece wanted to incorporate Constantinople to achieve the Megali Idea, but Entente powers did not give permission.

It was decided by the Triple Entente that Greece would control a zone around Smyrna (Izmir) and Ayvalik in western Asia Minor. The reason for these landings were prior Italian landings on the southern coast of Turkey, including in the city of Antalya. The Allies worried about further Italian expansion and saw Greek landings as a way to avoid this.

On 28 May, Greeks landed on Ayvalık. It was no surprise that this small town was chosen as this town was the Greek-speaking stronghold before the Balkan Wars. The Balkan Wars changed the nature of this region. The Muslim inhabitants who were forced out with the extending borders of Greece, mainly from Crete, settled in this area. Under an old Ottoman Lieutenant Colonel Ali Çetinkaya, these people formed a unit. Along Ali Çetinkaya′s units, population in the region gathered around Resit, Tevfik and Çerkes Ethem. These units were very determined to fight against Greece as there was no other place that they could be pushed back. Resit, Tevfik and Ethem were of Circassian origin who were expelled from their ancestral lands in the Caucasus by the Russians[citation needed]. They were settled around the Aegean coast. Greek troops first met with these irregulars. Mustafa Kemal asked Admiral Rauf Orbay if he could help in coordinating the units under Ali Çetinkaya, Resit, Tevfik and Çerkez Ethem. Rauf Orbay—also of Circassian origin—managed to link these groups. He asked them to cut the Greek logistic support lines.

The Allied decision to allow a Greek landing in Smyrna resulted from earlier Italian landings at Antalya. Faced with Italian annexation of parts of Asia Minor with a significant ethnic Greek population, Venizelos secured Allied permission for Greek troops to land in Smyrna, ostensibly in order to protect the civilian population from turmoil. Turks claim that Venizelos wanted to create a homogeneous Greek settlement to be able to annex it to Greece, and his public statements left little doubt about Greek intentions: "Greece is not making war against Islam, but against the anachronistic Ottoman Government, and its corrupt, ignominious, and bloody administration, with a view to the expelling it from those territories where the majority of the population consists of Greeks."[68]

Western active stage

Mustafa Kemal in İzmir, greeting people.

As soon as Greek forces landed in Smyrna, a Turkish nationalist opened fire prompting brutal reprisals. Greek forces used Smyrna as a base for launching attacks deeper into Anatolia. Mustafa Kemal refused to accept even a temporary Greek presence in Smyrna. Eventually, the Turkish nationalists with the aid of the Kemalist armed forces defeated the Greek troops and population and pushed them out of Smyrna and the rest of Anatolia.

Western resolution

With the borders secured with treaties and agreements at east and south, Mustafa Kemal was now in a commanding position. The Nationalists were then able to demand on 5 September 1922 that the Greeks evacuate East Thrace, Imbros and Tenedos as well as Asia Minor, and the Maritsa (Turkish Meriç) River should again become the western border of Turkey, as before 1914. The British were prepared to defend the neutral zone of Constantinople and the Straits and the French asked Kemal to respect it,[69] to which he agreed on 28 September.[70] However, France, Italy, Yugoslavia, and the British Dominions objected to a new war.[71]

France, Italy and Britain called on Mustafa Kemal to enter into cease-fire negotiations. In return, on 29 September Kemal asked for the negotiations to be started at Mudanya. Negotiations at Mudanya began on 3 October and it was concluded with the Armistice of Mudanya. This was agreed on 11 October, two hours before the British intended to engage at Chanak, and signed the next day. The Greeks initially refused to agree but did so on 13 October.[72] Factors persuading Turkey to sign may have included the arrival of British reinforcements.[73]

The armistice then made it possible for the allies to recognise the Turkish claim to East Thrace, which was agreed to at the Lausanne Conference on 20 November 1922.[74]

South

Çukurova Nationalist militias.

The French wanted to take control of Syria. With pressure against the French, Cilicia would be easily left to the nationalists. The Taurus Mountains were critical to the Ankara government. The French soldiers were foreign to the region and they were using Armenian militia to acquire their intelligence. Turkish nationals had been in cooperation with Arab tribes in this area. Compared to the Greek threat, they were the second most dangerous for the Ankara government. He proposed that if the Greek threat could be dispersed, the French would not resist.

Conference of London

In salvaging the Treaty of Sèvres, The Triple Entente forced the Turkish Revolutionaries to agree with the terms through a series of conferences in London. The Conference of London, with sharp differences, failed in both the first stage and the second stages. The modified Sèvres of the conference as a peace settlement was incompatible with the National Pact.

The conference of London gave the Triple Entente an opportunity to reverse some of its policies. In October, parties to the conference received a report from Admiral Mark Lambert Bristol. He organized a commission to analyze the situation, and inquire into the bloodshed during the Occupation of Izmir and the following activities in the region. The commission reported that if annexation would not follow, Greece should not be the only occupation force in this area. Admiral Bristol was not so sure how to explain this annexation to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson as he insisted on "respect for nationalities" in the Fourteen Points. He believed that the sentiments of the Turks "will never accept this annexation".

Neither the Conference of London nor Admiral Mark Lambert Bristol′s report changed British Prime Minister David Lloyd George′s position. On 12 February 1921, he went with the annexation of the Aegean coast which was followed by the Greek offensive. David Lloyd George acted with his sentiments, which were developed during Battle of Gallipoli, as opposed to General Milne, who was his officer on the ground.

Stage for peace

Soldiers on the way back.

The first communication between the sides was during the failed Conference of London. The stage for peace effectively began after the Triple Entente′s decision to make an arrangement with the Turkish revolutionaries. Before the talks with the Entente, the nationalists partially settled their eastern borders with the Democratic Republic of Armenia, signing Treaty of Alexandropol, but changes in the Caucasus—especially the establishment of the Armenian SSR—required one more round of talks. The outcome was the Treaty of Kars, a successor treaty to the earlier Treaty of Moscow of March 1921. It was signed in Kars with the Russian SFSR on 13 October 1921[75] and ratified in Yerevan on 11 September 1922.[76]

Armistice of Mudanya

The Marmara sea resort town of Mudanya hosted the conference to arrange the armistice on 3 October 1922. İsmet (İnönü)—commander of the western armies—was in front of the Allies. The scene was unlike Mondros as the British and the Greeks were on the defense. Greece was represented by the Allies.

The British still expected the GNA to make concessions. From the first speech, the British were startled as Ankara demanded fulfillment of the National Pact. During the conference, the British troops in Constantinople were preparing for a Kemalist attack. There was never any fighting in Thrace, as Greek units withdrew before the Turks crossed the straits from Asia Minor. The only concession that Ismet made to the British was an agreement that his troops would not advance any farther toward the Dardanelles, which gave a safe haven for the British troops as long as the conference continued. The conference dragged on far beyond the original expectations. In the end, it was the British who yielded to Ankara's advances.

The Armistice of Mudanya was signed on 11 October. By its terms, the Greek army would move west of the Maritsa, clearing Eastern Thrace to the Allies. The famous American author Ernest Hemingway was in Thrace at the time, and he covered the evacuation of Eastern Thrace of its Greek population. He has several short stories written about Thrace and Smyrna, which appear in his book In Our Time. The agreement came into force starting 15 October. Allied forces would stay in Eastern Thrace for a month to assure law and order. In return, Ankara would recognize continued British occupation of Constantinople and the Straits zones until the final treaty was signed.

Refet Bele was assigned to seize control of Eastern Thrace from the Allies. He was the first representative to reach the old capital. The British did not allow the hundred gendarmes who came with him. That resistance lasted until the next day.

Abolition of the sultanate

The form of government in Constantinople—resting on the sovereignty of the Sultan—had effectively ceased to exist when British forces occupied the city after World War I.[77] The law for the abolition of the sultanate was submitted to the GNA for voting. Furthermore, it was argued that although the caliphate had belonged to the Ottoman Empire, it rested on the Turkish state by its dissolution and the GNA would have the right to choose a member of the Ottoman family for the office of caliph. On 1 November, the GNA voted for the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate. The last Sultan left Turkey on 17 November 1922, in a British battleship on his way to Malta. This was the last act of the Ottoman Empire.

Conference of Lausanne

The 11-week Conference of Lausanne was held in Lausanne, Switzerland, during 1922 and 1923. Its purpose was the negotiation of a treaty to replace the Treaty of Sèvres, which, under the new government of the Grand National Assembly, was no longer recognised by Turkey.

The conference opened in November 1922, with representatives from the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Turkey. It heard speeches from Benito Mussolini of Italy and Raymond Poincaré of France. At its conclusion, Turkey assented to the political clauses and the "freedom of the straits", which was Britain's main concern. The matter of the status of Mosul was deferred, since Curzon refused to be budged on the British position that the area was part of Iraq. The British Iraq Mandate's possession of Mosul was confirmed by a League of Nations brokered agreement between Turkey and Great Britain in 1926. The French delegation, however, did not achieve any of their goals and on 30 January 1923 issued a statement that they did not consider the draft treaty to be any more than a "basis of discussion". The Turks therefore refused to sign the treaty. On 4 February 1923, Curzon made a final appeal to Ismet Pasha to sign, and when he refused the Foreign Secretary broke off negotiations and left that night on the Orient Express.

Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne, finally signed in July 1923, led to international recognition of the sovereignty of the Republic of Turkey as the successor state to the defunct Ottoman Empire.[78]

Establishment of the Republic

Hatıra-i Zafer (Memory of Victory) by Hasan Sabri in 1925.

A republic was proclaimed on 29 October 1923, in the new capital of Ankara. Mustafa Kemal was elected as the first President. In forming his government, he placed Mustafa Fevzi (Çakmak), Köprülü Kâzım (Özalp), and İsmet (İnönü) in important positions. They helped him to establish his subsequent political and social reforms in Turkey.

Kemal had long ago made up his mind to abolish the sultanate when the moment was ripe. After facing opposition from some members of the assembly, using his influence as a war hero, he managed to prepare a draft law for the abolition of the sultanate, which was then submitted to the National Assembly for voting. In that article, it was stated that the form of the government in Constantinople, resting on the sovereignty of an individual, had already ceased to exist when the British forces occupied the city after World War I.[77] Furthermore, it was argued that although the caliphate had belonged to the Ottoman Empire, it rested on the Turkish state by its dissolution and Turkish National Assembly would have right to choose a member of the Ottoman family in the office of caliph. On 1 November, The Turkish Grand Assembly voted for the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate. The last Sultan left Turkey on 17 November 1922, in a British battleship on his way to Malta. Such was the last act in the decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire.

The Conference of Lausanne began on 21 November 1922. İsmet İnönü was the leading Turkish negotiator. İnönü maintained the basic position of the Ankara government that it had to be treated as an independent and sovereign state, equal with all other states attending the conference. In accordance with the directives of Mustafa Kemal, while discussing matters regarding the control of Turkish finances and justice, the Capitulations, the Turkish Straits and the like, he refused any proposal that would compromise Turkish sovereignty.[79] Finally, after long debates, on 24 July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed. Ten weeks after the signature the Allied forces left Istanbul.[80]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turkish War of Independence. |

- Armenian Genocide

- Greek genocide

- Assyrian genocide

- Aftermath of World War I

- Timeline of the Turkish War of Independence

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- Turkish Medal of Independence

Footnotes

^ In August 1922 the Turkish Army formed 23 infantry divisions and 6 cavalry divisions. Equivalent to 24 infantry divisions and 7 cavalry divisions, if the additional 3 infantry regiments, 5 undersized border regiments, 1 cavalry brigade and 3 cavalry regiments are included (271,403 men total). The troops were distributed in Anatolia as follows:[8]Eastern Front: 2 infantry divisions, 1 cavalry division, Erzurum and Kars fortified areas and 5 border regiments (29,514 men); El-Cezire front (southeastern Anatolia, eastern region of the river Euphrates): 1 infantry division and 2 cavalry regiments (10,447 men); Central Army area: 1 infantry division and 1 cavalry brigade (10,000 men); Adana command: 2 battalions (500 men); Gaziantep area: 1 infantry regiment and 1 cavalry regiment (1,000 men); Interior region units and institutions: 12,000 men; Western Front: 18 infantry divisions and 5 cavalry divisions, if the independent brigade and regiments are included, 19 infantry divisions and 5.5 cavalry divisions (207,942 men).

^ According to some Turkish estimates the casualties were at least 120,000-130,000.[23]Western sources give 100,000 killed and wounded,[24][25] with a total sum of 200,000 casualties, taking into account that 100,000 casualties were solely suffered in August–September 1922.[26][27][28] Material losses, during the war, were enormous too.[29]

^ Mehmet Çavuş became Mehmet Kara according to the Surname Law in 1934.

^ Mehmet Çavuş's fire against the French in Dörtyol was misknown until near past. But Hasan Tahsin's firing was the first bullet in West Front

References

^ Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth century. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-27459-3..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ The Place of the Turkish Independence War in the American Press (1918-1923) by Bülent Bilmez: "...the occupation of western Turkey by the Greek armies under the control of the Allied Powers, the discord among them was evident and publicly known. As the Italians were against this occupation from the beginning, and started "secretly" helping the Kemalists, this conflict among the Allied Powers, and the Italian support for the Kemalists were reported regularly by the American press."

^ According to John R. Ferris, "Decisive Turkish victory in Anatolia... produced Britain's gravest strategic crisis between the 1918 Armistice and Munich, plus a seismic shift in British politics..." Erik Goldstein and Brian McKerche, Power and Stability: British Foreign Policy, 1865–1965, 2004 p. 139

^ A. Strahan claimed that: "The internationalisation of Constantinople and the Straits under the aegis of the League of Nations, feasible in 1919, was out of the question after the complete and decisive Turkish victory over the Greeks". A. Strahan, Contemporary Review, 1922.

^ Chester Neal Tate, Governments of the World: a Global Guide to Citizens' Rights and Responsibilities, Macmillan Reference USA/Thomson Gale, 2006, p. 205.

^ Ergün Aybars, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti tarihi I, Ege Üniversitesi Basımevi, 1984, pg 319-334 (in Turkish)

^ Turkish General Staff, Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi, Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225

^ ab Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: Kurtuluş Savaşı tarihi, Türkiye İş̧ Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2008,

ISBN 9944884472, page 339. (in Turkish)

^ Arnold J. Toynbee/Kenneth P Kirkwood, Turkey, Benn 1926, p. 92

^ History of the Campaign of Minor Asia, General Staff of Army, Directorate of Army History, Athens, 1967, p. 140: on June 11 (OC) 6,159 officers, 193,994 soldiers (=200,153 men)

^ A. A. Pallis: Greece's Anatolian Venture - and After, Taylor & Francis, p. 56 (footnote 5).

^ "When Greek meets Turk; How the Conflict in Asia Minor Is Regarded on the Spot - King Constantine's View", T. Walter Williams, The New York Times, 10 September 1922.

^ Isaiah Friedman: British Miscalculations: The Rise of Muslim Nationalism, 1918-1925, Transaction Publishers, 2012,

ISBN 1412847109, page 239

^ Charles à Court Repington: After the War, Simon Publications LLC, 2001,

ISBN 1931313733, page 67

^ Anahide Ter Minassian: La république d'Arménie. 1918-1920 La mémoire du siècle., éditions complexe, Bruxelles 1989

ISBN 2-87027-280-4, pg 220

^ "British in Turkey May Be Increased", The New York Times, 19 June 1920.

^ Jowett, Philip (20 July 2015). Armies of the Greek-Turkish War 1919–22. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 45. Retrieved 17 September 2016 – via Google Books.

^ ab Kate Fleet, Suraiya Faroqhi, Reşat Kasaba: The Cambridge History of Turkey Volume 4, Cambridge University Press, 2008,

ISBN 0-521-62096-1, p. 159.

^ ab Sabahattin Selek: Millî mücadele - Cilt I (engl.: National Struggle - Edition I), Burçak yayınevi, 1963, page 109. (in Turkish)

^ ab Ahmet Özdemir, Savaş esirlerinin Milli mücadeledeki yeri, Ankara University, Türk İnkılap Tarihi Enstitüsü Atatürk Yolu Dergisi, Edition 2, Number 6, 1990, pg 328-332

^ ab Σειρά Μεγάλες Μάχες: Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή (Νο 8), συλλογική εργασία, έκδοση περιοδικού Στρατιωτική Ιστορία, Εκδόσεις Περισκόπιο, Αθήνα, Νοέμβριος 2002, σελίδα 64 (in Greek)

^ Στρατιωτική Ιστορία journal, Issue 203, December 2013, page 67

^ Ali Çimen, Göknur Göğebakan: Tarihi Değiştiren Savaşlar, Timaş Yayınevi,

ISBN 9752634869, 2. Cilt, 2007, sayfa 321 (in Turkish)

^ Stephen Vertigans: Islamic Roots and Resurgence in Turkey: Understanding and Explaining the Muslim Resurgence, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003,

ISBN 0275980510, page 41.

^ Nicole Pope, Hugh Pope: Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey, Overlook Press, 2000,

ISBN 1585670960, page 58.

^ Stephen Joseph Stillwell, Anglo-Turkish relations in the interwar era, Edwin Mellen Press, 2003,

ISBN 0773467769, page 46.

^ Richard Ernest Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt Dupuy, The Harper encyclopedia of military history: from 3500 BC to the present,

ISBN 0062700561, HarperCollins, 1993, page 1087

^ Revue internationale d'histoire militaire - Issues 46-48, University of Michigan, 1980, page 227.

^ Robert W.D. Ball: Gun Digest Books, 2011,

ISBN 1440215448, page 237

^ Pars Tuğlacı: Tarih boyunca Batı Ermenileri, Pars Yayın, 2004,

ISBN 975-7423-06-8, p. 794.

^ Christopher J. Walker, Armenia: The Survival of a Nation, Croom Helm, 1980, p. 310.

^ Death by Government, Rudolph Rummel, 1994.

^

These are according to the figures provided by Alexander Miasnikyan, the President of the Council of People's Commissars of Soviet Armenia, in a telegram he sent to the Soviet Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin in 1921. Miasnikyan's figures were broken down as follows: of the approximately 60,000 Armenians who were killed by the Turkish armies, 30,000 were men, 15,000 women, 5,000 children, and 10,000 young girls. Of the 38,000 who were wounded, 20,000 were men, 10,000 women, 5,000 young girls, and 3,000 children. Instances of mass rape, murder and violence were also reported against the Armenian populace of Kars and Alexandropol: see Vahakn N. Dadrian. (2003). The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 360–361.

ISBN 1-57181-666-6.

^ Armenia : The Survival of a Nation, Christopher Walker, 1980.

^ Rummel, R.J. "Statistics Of Turkey's Democide Estimates, Calculations, And Sources". University of Hawai'i. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

^ "British to defend Ismid-Black Sea line", The New York Times, 19 July 1920.

^ "Greeks enter Brussa; Turkish raids go on", The New York Times, 11 July 1920.

^ "Turk Nationalists capture Beicos", The New York Times, 7 July 1920.

^ "Allies occupy Constantinople; seize ministries", The New York Times, 18 March 1920.

^ "British to fight rebels in Turkey", The New York Times, 1 May 1920.

^ Nurettin Türsan, Burhan Göksel: Birinci Askeri Tarih Semineri: bildiriler, 1983, page 42.

^

Mevlüt Çelebi: Millî Mücadele’de İtalyan İşgalleri (English: Italian occupations during the National Struggle), Journal of Atatürk Research Center, issue 26.

^ "Turkey, Mustafa Kemal and the Turkish War of Independence, 1919–23". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

^ "Turkish War of Independence". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

^ "Turkey, Section: Occupation and War of Independence". History.com Encyclopedia. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

^ Mango, Atatürk, chap. 10: Figures on a ruined landscape, pp. 157–85.

^ Erickson, Ordered To Die, chap. 1.

^ Nur Bilge Criss, Istanbul under Allied Occupation 1918–1923, p. 1

^ Paul C. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919-1920, Ohio University Press, 1974

ISBN 0-8142-0170-9

^ "The Armenian Legion and Its Destruction of the Armenian Community in Cilicia", Stanford J. Shaw, http://www.armenian-history.com/books/Armenian_legion_Cilicia.pdf

^ Karakese Municipality, Milli Mücadelede İlk Kurşunu Karakese'de Mehmet Çavuş (KARA MEHMET) Atmıştır (accessed 4 May 2012). (in Turkish)

^ Kaufman, Will; Macpherson, Heidi Slettedahl (2007). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. ABC-CLIO. p. 696. ISBN 1-85109-431-8.

^ The activities of commission is reported in Henry Churchill King, Charles Richard Crane (King-Crane Commission), "Report of American Section of Inter-allied Commission of Mandates in Turkey" published by American Section in 1919.

^ Erickson, Ordered To Die, chap. 8, extended story at the Cost section.

^ Richard G. Hovannisian, Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1967.

^ Andrew Mango, Atatürk, John Murray, 1999,

ISBN 978-0-7195-6592-2, p. 214.

^ Lord Kinross. The Rebirth of a Nation, Chap 19. "Kinross writes that the Erkân-i Harbiye Reis Muavini, ie the General Commander of the Ottoman Empire at the time was Fevzi Pasa, and old friend. Although he was temporarily absent, his substitute was Kâzim (Inanç) Pasa, another old friend. Neither Mehmet VI, nor the Prime Minister Damat Ferit had actually seen the actual order."

^ Lord Kinross. The Rebirth of a Nation, chap 19.

^ Lord Kinross. (1999) Atatürk: The Re-birth of a Nation, chap. 16.

^ Ardic, Nurullah. Islam and the Politics of Secularism. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

^ Vahide, Sukran (2012). Islam in Modern Turkey. SUNY Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780791482971. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

^ ab "History of Anadolu Agency". Archived from the original on 9 January 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

^ George F. Nafziger, Islam at War: A History, p. 132.

^ Stanford J. Shaw; Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. p. 344

^ ab Belgelerle Türk tarihi dergisi (Volumes 44-47), Menteş Kitabevi, 2000, p. 87. (in Turkish)

^ ab Haydar Çakmak: Türk dış politikası, 1919-2008, Platin, 2008,

ISBN 9944137251, page 126. (in Turkish)

^ Embassy of the Russian Federation in Turkey: Rusya Federasyonu’nun Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Büyükelçiliği tarafından yayınlanan ‘Yeni Rusya ve Yeni Türkiye: İşbirliğinin İlk Adımları (1920-1930'lu Yıllarda Rus-Türk İlişkileri)’ başlıklı broşür hk., accessed on 4 May 2012. (in Turkish)

^ "Not War Against Islam-Statement by Greek Prime Minister" in The Scotsman, 29 June 1920 p. 5

^ Harry J. Psomiades, The Eastern Question, the Last Phase: a Study in Greek-Turkish Diplomacy (Pella, New York 2000), 33.

^ A. L. Macfie, 'The Chanak affair (September–October 1922)' Balkan Studies 20(2) (1979), 332.

^ Psomiades, 27-8.

^ Psomiades, 35.

^ Macfie, 336.

^ Macfie, 341.

^ (in Russian) Text of the Treaty of Kars Archived 24 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "ANN/Groong -- Treaty of Berlin - 07/13/1878". Retrieved 17 September 2016.

^ ab Kinross, Rebirth of a Nation, p. 348

^ "Treaty of Lausanne - World War I Document Archive". Retrieved 17 September 2016.

^ Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, 365

^ Kinross, Atatürk, The Rebirth of a Nation, 373.

External links

- Stock Footage - Turkish recruits muster in the war for independence after WWI. Critical Past

- Stock Footage - Turkish revolutionaries arrive by ship in Samsun, Anatolia. Critical Past

- Stock Footage - French and British troops occupy Constantinople and administer their respective enclaves. They search Turkish civilians. Critical Past

- Stock Footage - Effects of World War I. Critical Past

Bibliography

Barber, Noel (1988). Lords of the Golden Horn: From Suleiman the Magnificent to Kemal Ataturk. London: Arrow. ISBN 978-0-09-953950-6.

- Dobkin, Marjorie Housepian, Smyrna: 1922 The Destruction of City (Newmark Press: New York, 1988).

ISBN 0-966 7451-0-8.

Kinross, Patrick (2003). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-84212-599-1. OCLC 55516821.

Kinross, Patrick (1979). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-08093-8.

Lengyel, Emil (1962). They Called Him Atatürk. New York: The John Day Co. OCLC 1337444.

Mango, Andrew (2002) [1999]. Ataturk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey (Paperback ed.). Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-58567-334-X.

- Mango, Andrew, The Turks Today (New York: The Overlook Press, 2004).

ISBN 1-58567-615-2.

Milton, Giles (2008). Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of Islam's City of Tolerance (Paperback ed.). London: Sceptre; Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 978-0-340-96234-3. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

Milton, Giles (2008). Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of a Christian City in the Islamic World. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01119-3.

- Pope, Nicole and Pope, Hugh, Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey (New York: The Overlook Press, 2004).

ISBN 1-58567-581-4.

Yapp, Malcolm (1987). The Making of the Modern Near East, 1792–1923. London; New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-49380-3.