Wilt Chamberlain

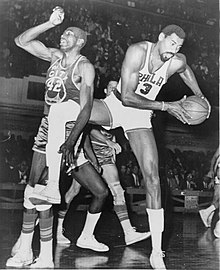

Chamberlain with the Harlem Globetrotters circa 1959 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | (1936-08-21)August 21, 1936 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | October 12, 1999(1999-10-12) (aged 63) Bel Air, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Listed height | 7 ft 1 in (2.16 m) |

| Listed weight | 275 lb (125 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Overbrook (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) |

| College | Kansas (1956–1958) |

| NBA draft | 1959 / Pick: Territorial |

| Selected by the Philadelphia Warriors | |

| Playing career | 1959–1973 |

| Position | Center |

| Number | 13 |

| Coaching career | 1973–1974 |

| Career history | |

| As player: | |

| 1958–1959 | Harlem Globetrotters |

1959–1965 | Philadelphia / San Francisco Warriors |

1965–1968 | Philadelphia 76ers |

1968–1973 | Los Angeles Lakers |

| As coach: | |

| 1973–1974 | San Diego Conquistadors |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career statistics | |

| Points | 31,419 (30.1 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 23,924 (22.9 rpg) |

| Assists | 4,643 (4.4 apg) |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |

Wilton Norman Chamberlain (/ˈtʃeɪmbərlɪn/; August 21, 1936 – October 12, 1999) was an American basketball player who played center position and is considered one of the most prominent and dominant players in NBA history.[1][2] He played for the Philadelphia/San Francisco Warriors, the Philadelphia 76ers, and the Los Angeles Lakers of the National Basketball Association (NBA). He played for the University of Kansas and also for the Harlem Globetrotters before playing in the NBA. Chamberlain stood 7 ft 1 in (2.16 m) tall, and weighed 250 pounds (110 kg) as a rookie[3] before bulking up to 275 and eventually to over 300 pounds (140 kg) with the Lakers.

Chamberlain holds numerous NBA records in scoring, rebounding, and durability categories. He is the only player to score 100 points in a single NBA game or average more than 40 and 50 points in a season. He won seven scoring, eleven rebounding, nine field goal percentage titles and led the league in assists once.[2] Chamberlain is the only player in NBA history to average at least 30 points and 20 rebounds per game in a season, which he accomplished seven times. He is also the only player to average at least 30 points and 20 rebounds per game over the entire course of his NBA career. Although he suffered a long string of losses in the playoffs,[4] Chamberlain had a successful career, winning two NBA championships, earning four regular-season Most Valuable Player awards, the Rookie of the Year award, one NBA Finals MVP award, and was selected to 13 All-Star Games and ten All-NBA First and Second teams.[1][5] He was subsequently enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1978, elected into the NBA's 35th Anniversary Team of 1980, and chosen as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History of 1996.[5]

Chamberlain was known by several nicknames during his basketball playing career. He hated the ones that called attention to his height, such as "Goliath" and "Wilt the Stilt". A Philadelphia sportswriter coined the nicknames during Chamberlain's high school days. He preferred "The Big Dipper", which was inspired by his friends who saw him dip his head as he walked through doorways.[6] After his professional basketball career ended, Chamberlain played volleyball in the short-lived International Volleyball Association, was president of that organization, and is enshrined in the IVA Hall of Fame for his contributions.[7] He was a successful businessman, authored several books, and appeared in the movie Conan the Destroyer. He was a lifelong bachelor and became notorious for his claim of having had sexual relations with as many as 20,000 women.[8]

Contents

1 Early years

2 High school career

3 College career

4 Professional career

4.1 Harlem Globetrotters (1958–1959)

4.2 Philadelphia/San Francisco Warriors (1959–1965)

4.3 Philadelphia 76ers (1965–1968)

4.4 Los Angeles Lakers (1968–1973)

4.5 San Diego Conquistadors (1973–1974)

5 NBA career statistics

5.1 Regular season

5.2 Playoffs

6 Post-NBA career

7 Legacy

7.1 Individual achievements and recognition

7.2 Chamberlain–Russell rivalry

7.3 Rule changes

7.4 Reputation

8 Personal life

8.1 Star status

8.2 Love life

8.3 Relationships

8.4 Politics

9 Death

10 See also

11 Notes

12 References

13 Further reading

14 External links

Early years

Chamberlain was born in 1936 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, into a family of nine children, the son of Olivia Ruth Johnson, a domestic worker and homemaker, and William Chamberlain, a welder, custodian, and handyman.[9] He was a frail child, nearly dying of pneumonia in his early years and missing a whole year of school as a result.[10] In his early years Chamberlain was not interested in basketball, because he thought it was "a game for sissies".[11] Instead, he was an avid track and field athlete: as a youth, he high jumped 6 feet, 6 inches, ran the 440 yards in 49.0 seconds and the 880 yards in 1:58.3, put the shot 53 feet, 4 inches, and broad jumped 22 feet.[12] But according to Chamberlain, "basketball was king in Philadelphia", so he eventually turned to the sport.[13] Because Chamberlain was a very tall child, already measuring 6 ft 0 in (1.83 m) at age 10[14] and 6 ft 11 in (2.11 m) when he entered Philadelphia's Overbrook High School,[2] he had a natural advantage against his peers; he soon was renowned for his scoring talent, his physical strength and his shot blocking abilities.[15] According to ESPN journalist Hal Bock, Chamberlain was "scary, flat-out frightening... before he came along, most basketball players were mortal-sized men. Chamberlain changed that."[16] It was also in this period of his life when his three lifelong nicknames "Wilt the Stilt", "Goliath", and his favorite, "The Big Dipper", were allegedly born.[1]

High school career

As the star player for the Overbrook Panthers, Chamberlain averaged 31 points a game during the 1953 high school season and led his team to a 71–62 win over Northeast High School, who had Guy Rodgers, Chamberlain's future NBA teammate. He scored 34 points as Overbrook won the Public League title and gained a berth in the Philadelphia city championship game against the winner of the rival Catholic league, West Catholic.[17] In that game, West Catholic quadruple-teamed Chamberlain the entire game, and despite the center's 29 points, the Panthers lost 54–42.[17] In his second Overbrook season, he continued his prolific scoring when he tallied a high school record 71 points against Roxborough.[18] The Panthers comfortably won the Public League title after again beating Northeast in which Chamberlain scored 40 points, and later won the city title by defeating South Catholic 74–50. He scored 32 points and led Overbrook to a 19–0 season.[18] During summer vacations, he worked as a bellhop in Kutsher's Hotel. Subsequently, owners Milton and Helen Kutsher kept up a lifelong friendship with Wilt, and according to their son Mark, "They were his second set of parents."[19]Red Auerbach, the coach of the Boston Celtics, spotted the talented teenager at Kutscher's and had him play 1-on-1 against University of Kansas standout and national champion, B. H. Born, elected the Most Outstanding Player of the 1953 NCAA Finals. Chamberlain won 25–10; Born was so dejected that he gave up a promising NBA career and became a tractor engineer ("If there were high school kids that good, I figured I wasn't going to make it to the pros"),[20] and Auerbach wanted him to go to a New England university, so he could draft him as a territorial pick for the Celtics, but Chamberlain did not respond.[20]

In Chamberlain's third and final Overbrook season, he continued his high scoring, logging 74, 78 and 90 points in three consecutive games.[21] The Panthers won the Public League a third time, beating West Philadelphia 78–60, and in the city championship game, they met West Catholic once again. Scoring 35 points, Chamberlain led Overbrook to an easy 83–42 victory.[21] After three years, Chamberlain had led Overbrook to two city championships, logged a 56–3 record and broken Tom Gola's high school scoring record by scoring 2,252 points, averaging 37.4 points per game.[1][4][22] After his last Overbrook season, more than two hundred universities tried to recruit the basketball prodigy.[2] Among others, UCLA offered Chamberlain the opportunity to become a movie star, the University of Pennsylvania wanted to buy him diamonds, and Chamberlain's Panthers coach Mosenson was even offered a coaching position if he could persuade the center.[23] In his 2004 biography of Chamberlain, Robert Cherry described that Chamberlain wanted a change and therefore did not want to go to or near Philadelphia (also eliminating New York), was not interested in New England, and snubbed the South because of racial segregation; this left the Midwest as Chamberlain's probable choice.[23] In the end, after visiting the University of Kansas and conferring with the school's renowned college coach Phog Allen, Chamberlain proclaimed that he was going to play college basketball at Kansas.[23]

At the ages of 16 and 17, Chamberlain played several professional games under the pseudonym "George Marcus".[24] There were contemporary reports of the games[25] in Philadelphia publications but he tried to keep them secret from the Amateur Athletic Union.

College career

In 1955, Chamberlain entered the University of Kansas. In his first year, he played for the Jayhawks freshman team under coach Phog Allen, whom he admired. Chamberlain was also a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, where he was the president of his pledge class.[26] Chamberlain's freshman debut was highly anticipated, and he delivered; the freshman squad was pitted against the varsity, who were favored to win their conference that year. Chamberlain dominated his older college players by scoring 42 points (16–35 from the field, 10–12 on free throws), grabbing 29 rebounds and registering four blocks.[12] Chamberlain's prospects of playing under Allen ended, however, when the coach turned 70 shortly after and retired in accordance with KU regulations. Chamberlain had a bad relationship with Allen's successor, Dick Harp, fueled by resentment and disappointment: Chamberlain biographer Robert Cherry has doubted whether Chamberlain would have chosen KU if he had known that Allen was going to retire.[27]

On December 3, 1956, Chamberlain made his varsity debut as a center. In his first game, he scored 52 points and grabbed 31 rebounds, breaking both all-time Kansas records in an 87–69 win against Northwestern, who had Chamberlain's future NBA teammate Joe Ruklick.[28] Teammate Monte Johnson testified to his athleticism: "Wilt ... had unbelievable endurance and speed ... and was never tired. When he dunked, he was so fast that a lot of players got their fingers jammed [between Chamberlain's hand and the rim]." Reportedly, Chamberlain also broke Johnny Kerr's toe with a slam dunk.[28] By this time, he had developed several offensive weapons that became his trademarks: his finger roll, his fade-away jump shot, which he could also hit as a bank shot, his passing and his shot-blocking.[28] Leading a talented squad of starters, including Maurice King, Gene Elstun, John Parker, Ron Lonesky and Lew Johnson, the Jayhawks went 13–1 until they lost a game 56–54 versus Oklahoma State, who held the ball the last three and a half minutes without any intention of scoring a basket, which was still possible in the days before the shot clock (introduced 1984 in the NCAA).[28] As he did at Overbrook, Chamberlain again showcased his diverse athletic talent. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10.9 seconds, shot-putted 56 feet, triple jumped more than 50 feet, and won the high jump in the Big Eight track and field championships three straight years.[29]

In 1957, 23 teams were selected to play in the NCAA Tournament. The Midwest regional was held in Dallas, Texas, which at the time was segregated. In the first game, the Jayhawks played the all-white SMU team, and KU player John Parker later said: "The crowd was brutal. We were spat on, pelted with debris, and subjected to the vilest racial epithets possible."[28] KU won 73–65 in overtime, after which police had to escort the Jayhawks out. The next game against Oklahoma City was equally unpleasant, with KU winning 81–61 under intense racist abuse.[28] In the semi-finals, Chamberlain's Jayhawks handily defeated the two-time defending national champion San Francisco, 80–56, with Wilt scoring 32 points, grabbing 11 rebounds, and having at least seven blocked shots. (Game film is unclear whether an 8th block occurred, or the ball just fell short due to Chamberlain's withering defensive intimidation). Chamberlain demonstrated his growing arsenal of offensive moves, including jump shots, put-backs, tip-ins, and his turnaround jump shot. He was far more comfortable and effective at the foul line than he would later be during his pro career. He had outstanding foot speed throughout the game, and several times led the fast break, including blocking a shot near the basket and then outracing the field for a layup. His stellar performance led Kansas to an insurmountable lead, and he rested on the bench for the final 3:45 remaining in the game.

Chamberlain was named on the first-team All-America squad and led the Jayhawks into the NCAA finals against the North Carolina Tar Heels. In that game, Tar Heels coach Frank McGuire used several unorthodox tactics to thwart Chamberlain. For the tip-off, he sent his shortest player, Tommy Kearns, in order to rattle Chamberlain, and the Tar Heels spent the rest of the night triple-teaming him, one defender in front, one behind, and a third arriving as soon as he got the ball.[4] With their fixation on Chamberlain, the Jayhawks shot only 27% from the field, as opposed to 64% of the Tar Heels, and trailed 22–29 at halftime.[28] Later, North Carolina led 40–37 with 10 minutes to go and stalled the game: they passed the ball around without any intention of scoring a basket. After several Tar Heel turnovers, the game was tied at 46 at the end of regulation.[28] In the first overtime each team scored two points, and in the second overtime, Kansas froze the ball in return, keeping the game tied at 48. In the third overtime, the Tar Heels scored two consecutive baskets, but Chamberlain executed a three-point play, leaving KU trailing 52–51. After King scored a basket, Kansas was ahead by one point, but then Tar Heel Joe Quigg was fouled on a drive with 10 seconds remaining and made his two foul shots. For the final play, Dick Harp called for Ron Loneski to pass the ball into Chamberlain in the low post. The pass was intercepted, however, and the Tar Heels won the game. Nonetheless, Chamberlain, who scored 23 points and 14 rebounds,[28] was elected the Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four.[4] Cherry has speculated, however, that this loss was a watershed in Chamberlain's life, because it was the first time that his team lost despite him putting up impressive individual stats. He later admitted that this loss was the most painful of his life.[28]

In Chamberlain's junior year of 1957–58, the Jayhawks' matches were even more frustrating for him. Knowing how dominant he was, the opponents resorted to freeze-ball tactics and routinely used three or more players to guard him.[30] Teammate Bob Billings commented: "It was not fun basketball ... we were just out chasing people throwing the basketball back and forth."[30] Nevertheless, Chamberlain averaged 30.1 points for the season and led the Jayhawks to an 18–5 record, losing three games while he was out with a urinary infection:[30] because KU came second in the league and at the time only conference winners were invited to the NCAA tourney, the Jayhawks' season ended. It was a small consolation that he was again named an All-American, along with future NBA Hall-of-Famers Elgin Baylor and Oscar Robertson plus old rival Guy Rodgers.[30] Having lost the enjoyment from NCAA basketball and wanting to earn money, he left college and sold the story named "Why I Am Leaving College" to Look magazine for $10,000, a large sum when NBA players earned $9,000 in a whole season.[30] In two seasons at Kansas, he averaged 29.9 points and 18.3 rebounds per game while totaling 1,433 points and 877 rebounds,[16] and led Kansas to one Big Seven championship.[5] By the time Chamberlain was 21 (even before he turned professional), he had already been featured in Time, Life, Look, and Newsweek magazines.[31]

For many years following Chamberlain's departure from the University of Kansas, critics claimed that he either wanted to leave the very white Midwest or was embarrassed by not being able to bring home the NCAA basketball tournament victory. In 1998, Chamberlain returned to Allen Field House in Lawrence, Kansas to participate in a jersey-retiring ceremony for his #13. Around this time, he has been quoted as saying: "There's been a lot of conversation, since people have been trying to get my jersey number retired, that I have some dislike for the University of Kansas. That is totally ridiculous."[32]

Professional career

Harlem Globetrotters (1958–1959)

After his frustrating junior year, Chamberlain wanted to become a professional player before finishing his senior year.[33] However, at that time, the NBA did not accept players until after their college graduating class had been completed. Therefore, Chamberlain was prohibited from joining the NBA for a year, and decided to play for the Harlem Globetrotters in 1958 for a sum of $50,000[1][4] (equal to about $434,000 today[note 1]).

Chamberlain became a member of the Globetrotters team that made history by playing in Moscow in 1959; the team enjoyed a sold-out tour of the USSR. Prior to the start of a game at Moscow's Lenin Central Stadium, they were greeted by General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev.[34] One particular Trotter skit involved Trotters captain Meadowlark Lemon collapsing to the ground, and instead of helping him up, Chamberlain threw him several feet high up in the air and caught him like a doll. "[Chamberlain] was the strongest athlete who ever lived", the 210-pound Lemon later recounted.[35] In later years, Chamberlain frequently joined the Trotters in the off-season and fondly recalled his time there, because he was no longer jeered at or asked to break records, but just one of several artists who loved to entertain the crowd.[36] On March 9, 2000, His number 13 was retired by the Trotters.[34]

Philadelphia/San Francisco Warriors (1959–1965)

On October 24, 1959, Chamberlain finally made his NBA debut, starting for the Philadelphia Warriors.[1] Chamberlain immediately became the NBA's highest paid player, when he signed for $30,000 (equal to about $258,000 today)[note 1] in his rookie contract. In comparison, the previous top earner was Bob Cousy of the Boston Celtics with $25,000; in fact, Eddie Gottlieb bought the whole Warriors franchise for $25,000 seven years earlier.[37]

Chamberlain grabs a rebound during a game against the New York Knickerbockers.

In the 1959–60 NBA season, Chamberlain joined a Warriors squad that was coached by Neil Johnston and included Hall-of-Fame guards Tom Gola and Paul Arizin, plus Ernie Beck and his old rival, Guy Rodgers; remarkably, all five starters were Philadelphians. In his first NBA game, against the New York Knicks, the rookie center scored 43 points and grabbed 28 rebounds.[38] In his fourth game, Philadelphia met the reigning champions, the Boston Celtics of Hall-of-Fame coach Red Auerbach, whose offer he had snubbed several years before, and Bill Russell, who was now lauded as one of the best defensive pivots in the game.[38] In what was the first of many Chamberlain-Russell match-ups, Chamberlain outscored Russell with 30 points versus 28 points, but Boston won the game. Chamberlain and his perennial nemesis would grow to become one of the NBA's greatest on-court rivalries of all time.[5] Nevertheless, the two also became friends off the court, similar to later rivals Magic Johnson and Larry Bird.[39]

In his first NBA season, Chamberlain averaged 37.6 points and 27 rebounds, convincingly breaking the previous regular-season records. He needed only 56 games to score 2,102 points, which broke the all-time regular season scoring record of Bob Pettit, who needed 72 games to score 2,101 points.[40] Chamberlain broke eight NBA records, and was named NBA MVP and Rookie of the Year that season, a feat matched only by fellow Hall-of-Famer Wes Unseld in the 1968–69 NBA season.[4][40] Chamberlain capped off his rookie season by winning the 1960 NBA All-Star Game MVP award with a 23-point, 25-rebound performance for the East. However, it also became evident that he was an atrocious free-throw shooter, making hardly half of his foul shots. As time progressed, Chamberlain grew even worse, and acknowledged he was simply a "psycho case" on that matter.[41] The Warriors entered the 1960 NBA Playoffs and beat the Syracuse Nationals, setting up a meeting versus the Eastern Division champions, the Boston Celtics. Cherry described how Celtics coach Red Auerbach ordered his forward Tom Heinsohn to commit personal fouls on Chamberlain: whenever the Warriors shot foul shots, Heinsohn grabbed and shoved Chamberlain to prevent him from running back quickly; his intention was that the Celtics would throw the ball in so fast that the prolific shotblocker Chamberlain was not yet back under his own basket, and Boston could score an easy fastbreak basket.[40] The teams split the first two games, but in Game 3, Chamberlain got fed up with Heinsohn and punched him. In the scuffle, Wilt injured his hand, and Philadelphia lost the next two games.[40] In Game 5, with his hand healthy, Chamberlain scored 50 points. But in Game 6, Heinsohn got the last laugh, scoring the decisive basket with a last-second tip-in.[40] The Warriors lost the series 4–2.[1]

The rookie Chamberlain then shocked Warriors' fans by saying he was thinking of retiring. He was tired of being double- and triple-teamed, and of teams coming down on him with hard fouls. Chamberlain feared he might lose his cool one day.[1] Celtics forward Heinsohn said: "Half the fouls against him were hard fouls ... he took the most brutal pounding of any player ever".[1] In addition, Chamberlain was seen as a freak of nature, jeered at by the fans and scorned by the media. As Chamberlain often said, quoting coach Alex Hannum's explanation of his situation, "Nobody loves Goliath."[4] Gottlieb coaxed Chamberlain back into the NBA, sweetening his return with a salary raise to $65,000[42] (equal to about $550,000 today).[note 1]

The following season, Chamberlain surpassed his rookie season statistics as he averaged 38.4 points and 27.2 rebounds per game. He became the first player to break the 3,000-point barrier and the first and still only player to break the 2,000-rebound barrier for a single season, grabbing 2,149 boards.[43] Chamberlain also won his first field goal percentage title, and set the all-time record for rebounds in a single game with 55.[4] Chamberlain was so dominant on the team that he scored almost 32% of his team's points and collected 30.4% of their rebounds.[42]

Chamberlain proudly displays the numbers of his record-setting 100-point game.

Chamberlain again failed to convert his play into team success, this time bowing out against the Syracuse Nationals in a three-game sweep.[44] Cherry noted that Chamberlain was "difficult" and did not respect coach Neil Johnston, who was unable to handle the star center. In retrospect, Gottlieb remarked: "My mistake was not getting a strong-handed coach.... [Johnston] wasn't ready for big time."[45] In Chamberlain's third season, the Warriors were coached by Frank McGuire, the coach who had masterminded Chamberlain's painful NCAA loss against the Tar Heels. In that year, Wilt set several all-time records which have never been threatened. In the 1962 season, he averaged 50.4 points and grabbed 25.7 rebounds per game.[43] On March 2, 1962, in Hershey, Pennsylvania, Wilt scored 100 points, shot 36 of 63 from the field, and made 28 of 32 free throws against the New York Knicks. Chamberlain's 4,029 regular-season points made him the only player to break the 4,000-point barrier;[1] the only other player to break the 3,000-point barrier is Michael Jordan, with 3,041 points in the 1986–87 NBA season. Chamberlain once again broke the 2,000-rebound barrier with 2,052. Additionally, he was on the hardwood for an average of 48.53 minutes, playing 3,882 of his team's 3,890 minutes.[43] Because Chamberlain played in overtime games, he averaged more minutes per game than the regulation 48; in fact, Chamberlain would have reached the 3,890-minute mark if he had not been ejected in one game after picking up a second technical foul with eight minutes left to play.[46]

His extraordinary feats in the 1962 season were later subject of the book Wilt, 1962 by Gary M. Pomerantz (2005), who used Chamberlain as a metaphor for the uprising of Black America.[47] In addition to Chamberlain's regular-season accomplishments, he scored 42 points in the 1962 NBA All-Star Game; a record that stood until broken by Anthony Davis in 2017.[48] In the 1962 NBA Playoffs, the Warriors met the Boston Celtics again in the Eastern Division Finals, a team which Bob Cousy and Bill Russell called the greatest Celtics team of all time.[49] Each team won their home games, so the series was split at three after six games. In a closely contested Game 7, Chamberlain tied the game at 107 with 16 seconds to go, but Celtics shooting guard Sam Jones hit a clutch shot with two seconds left to win the series for Boston.[49][50] In later years, Chamberlain was criticized for averaging 50 points, but not winning a title. In his defense, Warriors coach Frank McGuire said "Wilt has been simply super-human", and pointed out that the Warriors lacked a consistent second scorer, a playmaker, and a second big man to take pressure off Chamberlain.[41]

In the 1962–63 NBA season, Gottlieb sold the Warriors franchise for $850,000 (equal to about $7.04 million today)[note 1] to a group of businessmen led by Marty Simmons from San Francisco, and the team relocated to become the San Francisco Warriors under a new coach, Bob Feerick.[51] This also meant, however, that the team broke apart, as Paul Arizin chose to retire rather than move away from his family and his job at IBM in Philadelphia, and Tom Gola was homesick, requesting a trade to the lowly New York Knicks halfway through the season.[52] With both secondary scorers gone, Chamberlain continued his array of statistical feats, averaging 44.8 points and 24.3 rebounds per game that year.[43] Despite his individual success, the Warriors lost 49 of their 80 games and missed the playoffs.[53]

In the 1963–64 NBA season, Chamberlain got yet another new coach, Alex Hannum, and was joined by a promising rookie center, Nate Thurmond, who eventually entered the Hall of Fame. Ex-soldier Hannum, who later entered the Basketball Hall of Fame as a coach, was a crafty psychologist who emphasized defense and passing. Most importantly, he was not afraid to stand up to the dominant Chamberlain, who was known to "freeze out" (not communicate with) coaches he didn't like.[54] Backed up by valuable rookie Thurmond, Chamberlain had another good season with 36.9 ppg and 22.3 rpg,[43] and the Warriors went all the way to the NBA Finals. In that series they succumbed to Russell's Boston Celtics yet again, this time losing 4–1.[55] But as Cherry remarked, not only Chamberlain, but in particular Hannum deserved much credit because he had basically had taken the bad 31–49 squad of last year plus Thurmond and made it into an NBA Finalist.[56] In the summer of 1964, Chamberlain, one of the prominent participants at the famed Rucker Park basketball court in New York City,[57] made the acquaintance of a tall, talented 17-year-old who played there. Soon, the young Lew Alcindor was allowed into his inner circle, and quickly idolized the ten-year older NBA player. Chamberlain and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, as Alcindor would name himself later, would develop an intensely personal antipathy.[58] In the following 1964–65 NBA season, the Warriors got off to a terrible start and ran into financial trouble. At the 1965 All-Star break Chamberlain was traded to the Philadelphia 76ers, the new name of the relocated Syracuse Nationals. In return the Warriors received Paul Neumann, Connie Dierking, Lee Shaffer (who opted to retire rather than report to the Warriors), and $150,000[1][4] (equal to about $1.19 million today).[note 1] When Chamberlain left the Warriors, owner Franklin Mieuli said: "Chamberlain is not an easy man to love [and] the fans in San Francisco never learned to love him. Wilt is easy to hate [...] people came to see him lose."[33]

Philadelphia 76ers (1965–1968)

Chamberlain, 1967.

After the trade Chamberlain found himself on a promising Sixers team that included guards Hal Greer, a future Hall-of-Famer, and talented role players Larry Costello, Chet Walker and Lucious Jackson. Cherry remarks that there was a certain tension within the team: Greer was the formerly undisputed leader and was not willing to give up his authority, and Jackson, a talented center, was now forced to play power forward because Chamberlain blocked the center spot; however, as the season progressed, the three began to mesh better.[59] He did not care for the Sixers' coach, Dolph Schayes, because Schayes, according to him, had made several disrespectful remarks when they were rival players in the NBA.[59]

Statistically, Chamberlain was again outstanding, posting 34.7 ppg and 22.9 rpg for the second half of the season.[43] After defeating the Cincinnati Royals led by Oscar Robertson in the 1965 NBA Playoffs, the Sixers met Chamberlain's familiar rival, the Boston Celtics. The press called it an even matchup in all positions, even at center, where Bill Russell was expected to give Chamberlain a tough battle.[60] Indeed, the two teams split the first six games, and because of the better season record, the last game was held in the Celtics' Boston Garden. In that Game 7, both centers were marvelous: Chamberlain scored 30 points and 32 rebounds, and Russell logged 16 points, 27 rebounds and eight assists.[60] In the final minute, Chamberlain hit two clutch free throws and slam dunked on Russell, bringing Boston's lead down to 110–109 with five seconds left. Russell botched the inbounds pass, hitting a guy-wire over the backboard and giving the ball back to the Sixers. Coach Schayes called timeout, and decided to run the last play over Hal Greer rather than Chamberlain, because he feared the Celtics would intentionally foul him because he was a poor foul shooter. But when Greer attempted to inbound the ball, John Havlicek stole it to preserve the Celtics' lead.[61] For the fifth time in seven years, Russell's team deprived Chamberlain of the title.[1] According to Chamberlain, that was the time that people started calling him "loser".[4] Additionally, in an April 1965 issue of Sports Illustrated Chamberlain conducted an interview entitled "My Life in a Bush League" where he criticized his fellow players, coaches, and NBA administrators.[62] Chamberlain later commented that he could see in hindsight how the interview was instrumental in damaging his public image.[62]

In the 1965–66 NBA season the Sixers experienced tragedy when Ike Richman, the Sixers' co-owner as well as Chamberlain's confidant and lawyer, died of a coronary. The Sixers would post a 55–25 regular season record, and for his strong play, Chamberlain won his second MVP award.[5] In that season, the center again dominated his opposition by recording 33.5 points and 24.6 rebounds a game, leading the league in both categories.[43] In one particular game, Chamberlain blocked a dunk attempt by Gus Johnson so hard that he dislocated Johnson's shoulder.[63] Off the court, however, Chamberlain's commitment to the cause was doubted, as Chamberlain was a late sleeper, lived in New York and preferred to commute to Philadelphia rather than live there, and he was only available during the afternoon for training. Because Schayes did not want to risk angering his best player, he scheduled the daily workout at 4 pm; this angered the team, who preferred an early schedule to have the afternoon off, but Schayes just said: "There is no other way."[64] Irv Kosloff, who now owned the Sixers alone after Richman's death, pleaded to him to move to Philadelphia during the season, but he was turned down.[65]

In the 1966 NBA Playoffs, the Sixers again met the Celtics, and for the first time had home-court advantage. However, Boston easily won the first two games on the road, winning 115–96 and 114–93; Chamberlain played within his usual range, but his supporting cast shot under 40%. This caused sports journalist Joe McGinnis to comment: "The Celtics played like champions and the Sixers just played."[65] In Game 3, Chamberlain scored 31 points and 27 rebounds for an important road win, and the next day, coach Schayes planned to hold a joint team practice. However, Chamberlain said he was "too tired" to attend, and even refused Schayes' plea to at least show up and shoot a few foul shots with the team. In Game 4, Boston won 114–108.[65] Prior to Game 5, Chamberlain was nowhere to be found, skipping practice and being non-accessible. Outwardly, Schayes defended his star center as "excused from practice", but his teammates knew the truth and were much less forgiving.[65] In Game 5 itself, Chamberlain was superb, scoring 46 points and grabbing 34 rebounds, but the Celtics won the game 120–112 and the series.[66] Cherry is highly critical of Chamberlain: while conceding he was the only Sixers player who performed in the series, he pointed out his unprofessional, egotistical behavior as being a bad example for his teammates.[65] Prior to the 1966–67 NBA season, the friendly but unassertive Schayes was replaced by a familiar face, the crafty but firm Alex Hannum. In what Cherry calls a tumultuous locker room meeting, Hannum addressed several key issues he observed during the last season, several of them putting Chamberlain in an unfavorable light. Sixers forward Chet Walker testified that on several occasions, players had to pull Chamberlain and Hannum apart to prevent a fistfight.[67] Fellow forward Billy Cunningham observed that Hannum "never backed down" and "showed who was the boss". By doing this, he won Chamberlain's respect.[67] When emotions cooled off, Hannum pointed out to Chamberlain that he was on the same page in trying to win a title; but to pull this off, he – like his teammates – had to "act like a man" both on and off the court.[67] Concerning basketball, he persuaded him to change his style of play. Loaded with several other players who could score, such as future Hall-of-Famers Hal Greer and newcomer Billy Cunningham, Hannum wanted Chamberlain to concentrate more on defense.[4][68]

As a result, Chamberlain was less dominant, taking only 14% of the team's shots (in his 50.4 ppg season, it was 35.3%), but extremely efficient: he averaged a career-low 24.1 points, but he led the league in rebounds (24.2), ended third in assists (7.8), had a record breaking .683 field goal accuracy, and played strong defense.[43] His efficiency this season led him make 35 consecutive field goals over the course of four games in February.[69][70] For these feats, Chamberlain earned his third MVP award. The Sixers charged their way to a then-record 68–13 season, including a record 46–4 start.[1] In addition, the formerly egotistical Chamberlain began to praise his teammates, lauding hardworking Luke Jackson as the "ultimate power forward", calling Hal Greer a deadly jumpshooter, and point guard Wali Jones an excellent defender and outsider scorer.[67] Off the court, the center invited the team to restaurants and paid the entire bill, knowing he earned 10 times more than all the others.[67] Greer, who was considered a consummate professional and often clashed with the center because of his attitude, spoke positively of the new Chamberlain: "You knew in a minute the Big Fella [Chamberlain] was ready to go... and everybody would follow."[67]

Chamberlain and Nate Thurmond of the San Francisco Warriors competing in 1966.

In the 1967 NBA Playoffs, the Sixers yet again battled the Boston Celtics in the Eastern Division Finals, and again held home court advantage. In Game 1, the Sixers beat Boston 127–112, powered by Hal Greer's 39 points and Chamberlain's unofficial quadruple double, with 24 points, 32 rebounds, 13 assists and (unofficially counted) 12 blocks.[71] In Game 2, the Sixers won 107–102 in overtime, and player-coach Russell grudgingly praised Chamberlain for intimidating the Celtics into taking low percentage shots from further outside.[71] In Game 3, Chamberlain grabbed 41 rebounds and helped the Sixers win 115–104. The Celtics prevented a sweep by winning Game 4 with a 121–117 victory, but in Game 5, the Sixers simply overpowered the Celtics 140–116, which effectively ended Boston's historic run of eight consecutive NBA titles. The Sixers' center scored 29 points, 36 rebounds and 13 assists and was highly praised by Celtics Russell and K.C. Jones.[71]

In the 1967 NBA Finals, the Sixers were pitted against Chamberlain's old team, the San Francisco Warriors of his one-time backup Nate Thurmond and star forward Rick Barry. The Sixers won the first two games, with Chamberlain and Greer taking credit for respectively defensive dominance and clutch shooting, but San Francisco won two of the next three games, so Philadelphia was up 3–2 prior to Game 6.[71] In Game 6, the Warriors were trailing 123–122 with 15 seconds left. For the last play, Thurmond and Barry were assigned to do a pick and roll against Chamberlain and whoever would guard Barry. However, the Sixers foiled it: when Barry ran past Thurmond's pick and drove to the basket, he was picked up by Chet Walker, making it impossible to shoot; Thurmond was covered by Chamberlain, which made it impossible to pass. Barry botched his shot attempt, and the Sixers won the championship.[71] He said: "It is wonderful to be a part of the greatest team in basketball... being a champion is like having a big round glow inside of you."[71] He contributed with 17.7 ppg and 28.7 rpg against fellow future Hall-of-Fame pivot Nate Thurmond, never failing to snare at least 23 rebounds in the six games.[4][72] Chamberlain himself described the team as the best in NBA history.[43] In 2002, writer Wayne Lynch wrote a book about this remarkable Sixers season, Season of the 76ers, centering on Chamberlain. In the 1967–68 NBA season, matters began to turn sour between Chamberlain and the Sixers' sole surviving owner, Irv Kosloff. This conflict had been going along for a while: in 1965, Chamberlain asserted that he and the late Richman had worked out a deal which would give the center 25% of the franchise once he ended his career.[73] Although there is no written proof for or against, ex-Sixers coach Dolph Schayes and Sixers lawyer Alan Levitt assumed Chamberlain was right;[71] in any case, Kosloff declined the request, leaving Chamberlain livid and willing to jump to the rival ABA once his contract ended in 1967. Kosloff and Chamberlain worked out a truce, and later signed a one-year, $250,000 contract.[71]

On the hardwood, Chamberlain continued his focus on team play and registered 24.3 points and 23.8 rebounds a game for the season.[43] The 76ers had the best record in the league for the third straight season. Chamberlain made history by becoming the only center in NBA history to finish the season as the leader in assists, his 702 beating runner-up, Hall-of-Fame point guard Lenny Wilkens' total by 23.[22] Chamberlain likened his assist title to legendary home run hitter "Babe Ruth leading the league in sacrifice bunts", and he dispelled the myth that he could not and would not pass the ball.[74] For these feats, Chamberlain won his fourth and last MVP title.[5] Another landmark was his 25,000th point, making him the first ever player to score these many points: he gave the ball to his team physician Dr. Stan Lorber.[75] Winning 62 games, the Sixers easily took the first playoff berth of the 1968 NBA Playoffs. In the 1968 Eastern Division Semifinals, they were pitted against the Knicks. In a physically tough matchup, the Sixers lost sixth man Billy Cunningham with a broken hand, and Chamberlain, Greer and Jackson were struggling with inflamed feet, bad knees, and pulled hamstrings respectively. Going ahead 3–2, the Sixers defeated the Knicks 115–97 in Game 6 after Chamberlain scored 25 points and 27 rebounds: he had a successful series in which he led both teams in points (153), rebounds (145) and assists (38).[76]

In the 1968 Eastern Division Finals, the Sixers yet again met the Boston Celtics, again with home court advantage, and this time as reigning champions. Despite the Sixers' injury woes, coach Hannum was confident to "take the Celtics in less than seven games": he pointed out the age of the Celtics, who were built around Bill Russell and guard Sam Jones, both 34.[77] But then, national tragedy struck as Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. With eight of the ten starting players on the Sixers and Celtics being African-American, both teams were in deep shock, and there were calls to cancel the series.[77] In a game called "unreal" and "devoid of emotion", the Sixers lost 127–118 on April 5. After attending Dr. King's funeral, Chamberlain called out to the angry rioters who were setting fires all over the country, stating Dr. King would not have approved.[77] In Game 2, Philadelphia evened the series with a 115–106 victory, and won Games 3 and 4, with Chamberlain suspiciously often played by Celtics backup center Wayne Embry, causing the press to speculate Russell was worn down.[77] Prior to Game 5, the Celtics seemed dead: no NBA team had overcome a 3–1 series deficit before.[77] However, the Celtics rallied back, winning Games 5 and 6 122–104 and 114–106 respectively, powered by a spirited John Havlicek and helped by the Sixers' terrible shooting.[77]

What followed was the first of three consecutive controversial and painful Game 7s in which Chamberlain played. In that Game 7, the Sixers could not get their act together: 15,202 stunned Philadelphia fans witnessed a historic 100–96 defeat, making it the first time in NBA history a team lost a series after leading three games to one. Although Cherry points out that the Sixers shot badly (Hal Greer, Wali Jones, Chet Walker, Luke Jackson and Matt Guokas hit a combined 25 of 74 shots) and Chamberlain grabbed 34 rebounds and shot 4-of-9, the center himself scored only 14 points.[77] In the second half of Game 7, Chamberlain did not attempt a single shot from the field.[68] Cherry observes a strange pattern in that game: in a typical Sixers game, Chamberlain got the ball 60 times in the low post, but only 23 times in Game 7, and only seven times in the third and only twice in the fourth quarter.[77] Chamberlain later blamed coach Hannum for the lack of touches, a point which the coach conceded himself, but Cherry points out that Chamberlain, who always thought of himself as the best player of all time, should have been outspoken enough to demand the ball himself.[77] The loss meant that Chamberlain was now 1–6 in playoff series against the Celtics.

After that season, coach Alex Hannum wanted to be closer to his family on the West Coast; he left the Sixers to coach the Oakland Oaks in the newly founded American Basketball Association.[78] Chamberlain then asked for a trade, and Sixers general manager Jack Ramsay traded him to the Los Angeles Lakers for Darrall Imhoff, Archie Clark and Jerry Chambers.[68] The motivation for this move remains in dispute. According to sportswriter Roland Lazenby, a journalist close to the Lakers, Chamberlain was angry at Kosloff for breaking the alleged Richman-Chamberlain deal,[33] but according to Dr. Jack Ramsay, who was the Sixers general manager then, Chamberlain also threatened to jump to the ABA after Hannum left, and forced the trade himself.[68] Cherry finally adds several personal reasons: the center felt he had grown too big for Philadelphia, sought the presence of fellow celebrities (which were plenty in L.A.) and finally also desired the opportunity to date white women, which was possible for a black man in L.A. but hard to imagine elsewhere back then.[79]

Los Angeles Lakers (1968–1973)

Chamberlain playing for the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1969 NBA Finals against the Boston Celtics.

On July 9, 1968, Chamberlain was the centerpiece of a major trade between the 76ers and the Los Angeles Lakers, who sent center Darrall Imhoff, forward Jerry Chambers and guard Archie Clark to Philadelphia, making it the first time a reigning NBA Most Valuable Player was traded the next season.[80] Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke gave Chamberlain an unprecedented contract, paying him $250,000 after taxes (about $1.8 million in real value); in comparison, previous Lakers top earner Jerry West was paid $100,000 before taxes (about $720,000 in real value).[81]

Chamberlain joined a squad which featured Hall-of-Fame forward Elgin Baylor and Hall-of-Fame guard Jerry West, along with backup center Mel Counts, forwards Keith Erickson and Tom Hawkins and talented 5'11" guard Johnny Egan. The lack of a second guard next to West (and thus, the lack of speed and quickness) concerned coach Butch Van Breda Kolff; after losing Clark and Gail Goodrich, who joined the Phoenix Suns after the 1968 expansion draft, he said: "Egan gets murdered on defense because of his [lack of] size...but if I don't play him, we look like a bunch of trucks."[82] In addition, Cherry observed that Chamberlain was neither a natural leader nor a loyal follower, which made him difficult to fit in.[81] While he was on cordial terms with Jerry West, he often argued with team captain Elgin Baylor; regarding Baylor, he later explained: "We were good friends, but... [in] black culture... you never let the other guy one-up you."[81] The greatest problem was his tense relationship with Lakers coach Butch Van Breda Kolff: pejoratively calling the new recruit "The Load", he later complained that Chamberlain was egotistical, never respected him, too often slacked off in practice and focused too much on his own statistics.[81] In return, the center blasted Van Breda Kolff as "the dumbest and worst coach ever".[33][81] Laker Keith Erickson observed that "Butch catered to Elgin and Jerry...and that is not a good way to get on Wilt's side...that relationship was doomed from the start."[81]

Chamberlain experienced a problematic and often frustrating season. Van Breda Kolff benched him several times, which never happened in his career before; in mid-season, the perennial scoring champion had two games in which he scored only six and then only two points.[82] Playing through his problems, Chamberlain averaged 20.5 points and 21.1 rebounds a game that season.[43] However, Jack Kent Cooke was pleased, because since acquiring Chamberlain, ticket sales went up by 11%.[82] In the 1969 NBA Playoffs, the Lakers dispatched Chamberlain's old club, the San Francisco Warriors 4–2 after losing the first two games, and then defeated the Atlanta Hawks and met Chamberlain's familiar rivals, Bill Russell's Boston Celtics.[82] Going into the series as 3-to-1 favorites, the Lakers won the first two games, but dropped the next two. Chamberlain was criticized as a non-factor in the series, getting neutralized by Bill Russell with little effort.[82] But in Game 5, the Lakers center scored 13 points and grabbed 31 rebounds, leading Los Angeles to a 117–104 win. In Game 6, the Celtics won 99–90, and Chamberlain only scored 8 points; Cherry accuses him of choking, because if "Chamberlain had come up big and put up a normal 30 point scoring night", L.A. would have probably won its first championship.[82]

Game 7 featured a surreal scene: in anticipation of a Lakers win, Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke put up thousands of balloons in the rafters of the Forum in Los Angeles. This display of arrogance motivated the Celtics.[82] In Game 7, the Lakers trailed 91–76 after three quarters. The Lakers mounted a comeback; then Chamberlain twisted his knee after a rebound and had to be replaced by Mel Counts. With three minutes to go the Lakers trailed 103–102. The Lakers committed costly turnovers and lost the game 108–106, despite a triple-double from West, who had 42 points, 13 rebounds and 12 assists. West became the only player in NBA history to be named Finals MVP despite being on the losing team.[82] After the game, many wondered why Chamberlain sat out the final six minutes. At the time of his final substitution, he had scored 18 points (hitting seven of his eight shots) and grabbed 27 rebounds, significantly better than the 10 points of Mel Counts on 4-of-13 shooting.[82] Among others, Bill Russell didn't believe Chamberlain's injury was grave, and openly accused him of being a malingerer: "Any injury short of a broken leg or a broken back is not enough."[82] Ironically, Van Breda Kolff came to Chamberlain's defense, insisting the often-maligned Lakers center hardly was able to move in the end.[82] He himself was perceived as "pig-headed" for benching Chamberlain, and soon resigned as Lakers coach.[82] Cherry comments that according to some journalists, that Game 7 "destroyed two careers: Wilt's because he wouldn't take over and Van Breda Kolff because he wouldn't give in".[82]

In his second year with the Lakers under new coach Joe Mullaney, Chamberlain seriously injured his knee. He was injured in the ninth game of the schedule, suffering a total rupture of the patellar tendon at the base of his right kneecap,[83] and missed the next several months before appearing in the final three games of the 82-game regular season. Owing to a great start, he managed to average 27.3 points, 18.4 rebounds and 4.1 assists per game.[43] Again, the Lakers charged through the playoffs, and in the 1970 NBA Finals, the Lakers were pitted against the New York Knicks, loaded with future Hall-of-Famers Willis Reed, Dave DeBusschere, Bill Bradley, and Walt Frazier. Cherry observed that Reed, a prolific midrange shooter, was a bad matchup for Chamberlain: having lost lateral quickness due to his injury, the Lakers center was often too slow to block Reed's preferred high post jump shots.[84] In Game 1, New York masterminded a 124–112 win in which Reed scored 37 points. In Game 2, Chamberlain scored 19 points, grabbed 24 rebounds, and blocked Reed's shot in the final seconds, leading the Lakers to a 105–103 win.[84] Game 3 saw Jerry West famously hit a 60-foot shot at the buzzer to tie the game at 102; however, the Knicks took the game 111–108.[84] In Game 4, Chamberlain scored 18 points and grabbed 25 rebounds and helped tie the series at 2.[84] In Game 5, with the Knicks trailing by double digits, Reed pulled his thigh muscle and seemed to be done for the series. By conventional wisdom, Chamberlain now should have dominated against little-used Knicks backup centers Nate Bowman and Bill Hosket or forwards Bradley and DeBusschere, who gave up more than half a foot against the Lakers center.[84] Instead, the Lakers gave away their 13-point halftime lead and succumbed to the aggressive Knicks defense: L.A. committed 19 second half turnovers, and the two main scorers Chamberlain and West shot the ball only three and two times, respectively, in the entire second half.[84] The Lakers lost 107–100 in what was called one of the greatest comebacks in NBA Finals history.[84] In Game 6, Chamberlain scored 45 points, grabbed 27 rebounds and almost single-handedly equalized the series in a 135–113 Lakers win, and with Reed out, the Knicks seemed doomed prior to Game 7 in New York.[84]

However, the hero of that Game 7 was Willis Reed. He famously hobbled up court, scored the first four points, and inspired his team to one of the most famous playoff upsets of all time.[85] The Knicks led by 27 at halftime, and despite scoring 21 points, Chamberlain couldn't prevent a third consecutive loss in a Game 7. The Lakers center himself was criticized for his inability to dominate his injured counterpart, but Cherry pointed out that his feat – coming back from a career-threatening injury himself – was too quickly forgotten.[84]

Elmore Smith and Chamberlain fighting for a rebound in 1971.

In the 1970–71 NBA season, the Lakers made a notable move by signing future Hall-of-Fame guard Gail Goodrich, who came back from the Phoenix Suns after playing for L.A. until 1968. Chamberlain averaged 20.7 points, 18.2 rebounds and 4.3 assists,[43] once again led the NBA in rebounding and the Lakers won the Pacific Division title. After losing Elgin Baylor to an Achilles tendon rupture that effectively ended his career, and especially after losing Jerry West after a knee injury, the handicapped Lakers were seen as underdogs against the Milwaukee Bucks of freshly crowned MVP Lew Alcindor, and veteran Hall-of-Fame guard Oscar Robertson in the Western Conference Finals. Winning the regular season with 66 wins, the Bucks were seen as favourites against the depleted Lakers; still, many pundits were looking forward to the matchup between the 34-year-old Chamberlain and the 24-year-old Alcindor.[86] In Game 1, Abdul-Jabbar outscored Chamberlain 32–22, and the Bucks won 106–85. In Game 2, the Bucks won again despite the Lakers center scoring 26 points, four more than his Milwaukee counterpart. Prior to Game 3, things became even worse for the Lakers when Keith Erickson, West's stand-in, had an appendectomy and was out for the season; with rookie Jim McMillian easing the scoring pressure, Chamberlain scored 24 points and grabbed 24 rebounds in a 118–107 victory, but the Bucks defeated the Lakers 117–94 in Game 4 to take a 3–1 series lead. Milwaukee closed out the series at home with a 116–98 victory in Game 5.[87] Although Chamberlain lost, he was lauded for holding his own against MVP Alcindor, who was not only 10 years younger, but healthy.[86]

After the 1971 playoffs, Chamberlain challenged heavyweight boxing legend Muhammad Ali to a fight. The 15-round bout would have taken place on July 26, 1971 in the Houston Astrodome. Chamberlain trained with Cus d'Amato, but later backed out, withdrawing the much-publicized challenge,[88][22] by way of a contractual escape clause which predicated the Chamberlain-Ali match on Ali beating Joe Frazier in a fight scheduled for early 1971, which became Ali's first professional loss, enabling Chamberlain to legally withdraw from the bout.[89] In a 1999 interview, Chamberlain stated that boxing trainer Cus D'Amato had twice before, in 1965 and 1967, approached the basketball star with the idea, and that he and Ali had each been offered $5 million for the bout. In 1965, Chamberlain had consulted his father, who had seen Ali fight, and finally said no.[90][91] Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke had also offered Chamberlain a record-setting contract on the condition that Chamberlain agree to give up what Cooke termed "this boxing foolishness."[92] In 1967, recently retired NFL star Jim Brown acted as Chamberlain's manager, but Ali's manager Jabir Herbert Muhammad backed out of the Chamberlain-Ali match which was slated to take place at Madison Square Garden.[93]

In the 1971–72 NBA season, the Lakers hired former Celtics star guard Bill Sharman as head coach. Sharman introduced morning shoot-arounds, in which the perennial latecomer Chamberlain regularly participated (in contrast to earlier years with Dolph Schayes) and transformed him into a defensive-minded, low-scoring post defender in the mold of his old rival Bill Russell.[94] Furthermore, he told Chamberlain to use his rebounding and passing skills to quickly initiate fastbreaks to his teammates.[95] While no longer being the main scorer, Chamberlain was named the new captain of the Lakers: after rupturing his Achilles tendon, perennial captain Elgin Baylor retired, leaving a void the center now filled. Initially, Sharman wanted Chamberlain and West to share this duty, but West declined, stating he was injury-prone and wanted to solely concentrate on the game.[96] Chamberlain accepted his new roles and posted an all-time low 14.8 points, but also won the rebound crown with 19.2 rpg and led the league with a .649 field goal percentage.[43] Powered by his defensive presence, the Lakers embarked on an unprecedented 33-game win streak en route to a then-record 69 wins in the regular season. Yet the streak led to one strangely dissonant event. According to Flynn Robinson, after the record-setting streak, Lakers owner Cooke sought to reward each of his players—who were expecting perhaps a "trip to Hawaii"—with a $5 pen set. In response, Chamberlain "had everybody put all the pens in the middle of the floor and stepped on them."[97]

In the post-season, the Lakers swept the Chicago Bulls, then went on to face the Milwaukee Bucks of young superstar center and regular-season MVP Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (formerly Lew Alcindor).[citation needed] The matchup between Chamberlain and Abdul-Jabbar was hailed by Life magazine as the greatest matchup in all of sports. Chamberlain would help lead the Lakers past Abdul-Jabbar and the Bucks in six games.[citation needed] Particularly, Chamberlain was lauded for his performance in Game 6, which the Lakers won 104–100 after trailing by 10 points in the fourth quarter: he scored 24 points and 22 rebounds, played all 48 minutes and outsprinted the younger Bucks center on several late Lakers fast breaks.[98] Jerry West called it "the greatest ball-busting performance I have ever seen."[98] Chamberlain performed so well in the series that Time magazine stated, "In the N.B.A.'s western division title series with Milwaukee, he (Chamberlain) decisively outplayed basketball's newest giant superstar, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, eleven years his junior."[99]

Chamberlain with the Lakers in 1972

In the 1972 NBA Finals, the Lakers again met the New York Knicks; the Knicks were shorthanded after losing 6'9" Willis Reed to injury, and so, undersized 6'8" Jerry Lucas had the task to defend against the 7'1" Chamberlain.[100] However, prolific outside shooter Lucas helped New York to win Game 1, hitting nine of his 11 shots in the first half alone; in Game 2, which the Lakers won 106–92, Chamberlain put Lucas into foul trouble, and the Knicks lost defensive power forward Dave DeBusschere to injury.[100] In Game 3, Chamberlain scored 26 points and grabbed 20 rebounds for another Lakers win, and in a fiercely battled Game 4, the Lakers center was playing with five fouls late in the game. Having never fouled out in his career – a feat that he was very proud of – he played aggressive defense despite the risk of fouling out, and blocked two of Lucas' shots in overtime, proving those wrong who said he only played for his own stats; he ended scoring a game-high 27 points.[100] But in that game, he fell on his right hand, and was said to have "sprained" it; it was actually broken. For Game 5, Chamberlain's hands were packed into thick pads normally destined for defensive linesmen in American Football; he was offered a painkilling shot, but refused because he feared he would lose his shooting touch if his hands became numb.[100] In Game 5, Chamberlain recorded 24 points, 29 rebounds, eight assists and eight blocked shots. (While blocked shots were not an official NBA stat at that time, announcer Keith Jackson counted the blocks during the broadcast.[citation needed]) Chamberlain's outstanding all-around performance helped the Lakers win their first championship in Los Angeles with a decisive 114–100 win.[100] Chamberlain was named Finals MVP,[43] and was admired for dominating the Knicks in Game 5 while playing injured.[100]

The 1972–73 NBA season was to be Chamberlain's last, although he didn't know this at the time. In his last season, the Lakers lost substance: Happy Hairston was injured, Flynn Robinson and LeRoy Ellis had left, and veteran Jerry West struggled with injury.[101] Chamberlain averaged 13.2 points and 18.6 rebounds, still enough to win the rebounding crown for the 11th time in his career. In addition, he shot an NBA record .727% for the season, bettering his own mark of .683 from the 1966–67 season.[43] It was the ninth time Chamberlain would lead the league in field goal percentage. The Lakers won 60 games in the regular season and reached the 1973 NBA Finals against the New York Knicks. This time, the tables were turned: the Knicks now featured a healthy team with a rejuvenated Willis Reed, and the Lakers were now handicapped by several injuries.[101] In that series, the Lakers won Game 1 115–112, but the Knicks won Games 2 and 3; things worsened when Jerry West injured his hamstring yet again. In Game 4, the shorthanded Lakers were no match for New York, and in Game 5, the valiant, but injured West and Hairston had miserable games, and despite Chamberlain scoring 23 points and grabbing 21 rebounds, the Lakers lost 102–93 and the series.[102][103] After the Knicks finished off the close fifth game with a late flourish led by Earl Monroe and Phil Jackson, Chamberlain made a dunk with one second left, which turned out to be the last play of his NBA career.

San Diego Conquistadors (1973–1974)

In 1973, the San Diego Conquistadors of the NBA rival league ABA signed Chamberlain as a player-coach for a $600,000 salary.[104] However, the Lakers sued their former star and successfully prevented him from actually playing, because he still owed them the option year of his contract.[4] Barred from playing, Chamberlain mostly left the coaching duties to his assistant Stan Albeck, who recalled: "Chamberlain... has a great feel for pro basketball... [but] the day-to-day things that are an important part of basketball... just bored him. He did not have the patience."[104] The players were split on Chamberlain, who was seen as competent, but often indifferent and more occupied with promotion of his autobiography Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-Foot Black Millionaire Who Lives Next Door than with coaching. He once skipped a game to sign autographs for the book.[104] In his single season as a coach, the Conquistadors went a mediocre 37–47 in the regular season and lost against the Utah Stars in the Division Semifinals.[104] However, Chamberlain was not pleased by the Qs' meager attendance: crowds averaged 1,843, just over half of the Qs' small San Diego 3,200-seat sports arena.[104] After the season, Chamberlain retired from professional basketball.

NBA career statistics

| Legend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP | Games played | MPG | Minutes per game | ||

| FG% | Field-goal percentage | FT% | Free-throw percentage | ||

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | ||

| PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high | ||

| † | Denotes seasons in which Chamberlain won an NBA championship |

| * | Led the league |

| NBA record |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1959–60 | Philadelphia | 72 | 46.4* | .461 | .582 | 27.0* | 2.3 | 37.6* |

1960–61 | Philadelphia | 79* | 47.8* | .509* | .504 | 27.2 | 1.9 | 38.4* |

1961–62 | Philadelphia | 80* | 48.5 | .506 | .613 | 25.7* | 2.4 | 50.4 |

1962–63 | San Francisco | 80* | 47.6* | .528* | .593 | 24.3* | 3.4 | 44.8* |

1963–64 | San Francisco | 80* | 46.1* | .524 | .531 | 22.3 | 5.0 | 36.9* |

1964–65 | San Francisco | 38 | 45.9 | .499* | .416 | 23.5 | 3.1 | 38.9* |

1964–65 | Philadelphia | 35 | 44.5 | .528* | .526 | 22.3 | 3.8 | 30.1* |

1965–66 | Philadelphia | 79 | 47.3* | .540* | .513 | 24.6* | 5.2 | 33.5* |

1966–67† | Philadelphia | 81* | 45.5* | .683* | .441 | 24.2* | 7.8 | 24.1 |

1967–68 | Philadelphia | 82 | 46.8* | .595* | .380 | 23.8* | 8.6* | 24.3 |

1968–69 | Los Angeles | 81 | 45.3* | .583* | .446 | 21.1* | 4.5 | 20.5 |

1969–70 | Los Angeles | 12 | 42.1 | .568 | .446 | 18.4 | 4.1 | 27.3 |

1970–71 | Los Angeles | 82 | 44.3 | .545 | .538 | 18.2* | 4.3 | 20.7 |

1971–72† | Los Angeles | 82 | 42.3 | .649* | .422 | 19.2* | 4.0 | 14.8 |

1972–73 | Los Angeles | 82* | 43.2 | .727 | .510 | 18.6* | 4.5 | 13.2 |

| Career | 1045 | 45.8 | .540 | .511 | 22.9 | 4.4 | 30.1 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1960 | Philadelphia | 9 | 46.1 | .496 | .445 | 25.8 | 2.1 | 33.2 |

1961 | Philadelphia | 3 | 48.0 | .489 | .553 | 23.0 | 2.0 | 37.0 |

1962 | Philadelphia | 12 | 48.0 | .467 | .636 | 26.6 | 3.1 | 35.0 |

1964 | San Francisco | 12 | 46.5 | .543 | .475 | 25.2 | 3.3 | 34.7 |

1965 | Philadelphia | 11 | 48.7 | .530 | .559 | 27.2 | 4.4 | 29.3 |

1966 | Philadelphia | 5 | 48.0 | .509 | .412 | 30.2 | 3.0 | 28.0 |

1967† | Philadelphia | 15 | 47.9 | .579 | .388 | 29.1 | 9.0 | 21.7 |

1968 | Philadelphia | 13 | 48.5 | .534 | .380 | 24.7 | 6.5 | 23.7 |

1969 | Los Angeles | 18 | 46.2 | .545 | .392 | 24.7 | 2.6 | 13.9 |

1970 | Los Angeles | 18 | 47.3 | .549 | .406 | 22.2 | 4.5 | 22.1 |

1971 | Los Angeles | 12 | 46.2 | .455 | .515 | 20.2 | 4.4 | 18.3 |

1972† | Los Angeles | 15 | 46.9 | .563 | .492 | 21.0 | 3.3 | 14.7 |

1973 | Los Angeles | 17 | 47.1 | .552 | .500 | 22.5 | 3.5 | 10.4 |

| Career | 160 | 47.2 | .522 | .465 | 24.5 | 4.2 | 22.5 | |

Post-NBA career

After his stint with the Conquistadors, Chamberlain successfully went into business and entertainment, made money in stocks and real estate, bought a popular Harlem nightclub, which he renamed Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise, and invested in broodmares.[36] Chamberlain also sponsored his personal professional volleyball and track and field teams, and also provided high-level teams for girls and women in basketball, track, volleyball and softball,[105] and made money by appearing in ads for TWA, American Express, Volkswagen, Drexel Burnham, Le Tigre Clothing and Foot Locker.[36] After his basketball career, volleyball became Chamberlain's new passion: being a talented hobby volleyballer during his Lakers days,[102] he became board member of the newly founded International Volleyball Association in 1974 and became its president one year later.[7] As a testament to his importance, the IVA All-Star game was televised only because Chamberlain also played in it: he rose to the challenge and was named the game's MVP.[7] He played occasional matches for the IVA Seattle Smashers before the league folded in 1979. Chamberlain promoted the sport so effectively that he was named to the Volleyball Hall of Fame: he became one of the few athletes who were enshrined in different sports.[7]

Chamberlain statue in South Philadelphia

In 1976 Wilt turned to his interest in movies, forming a film production and distribution company to make his first film, entitled "Go For It".[106][107] Starting in the 1970s, he formed Wilt's Athletic Club, a track and field club in southern California,[108] coached by then UCLA assistant coach Bob Kersee in the early days of his career. Among the members of the team were: Florence Griffith, before she set the current world records in the 100 meters and 200 meters; three time world champion Greg Foster;[109] and future Olympic Gold medalists Andre Phillips, Alice Brown, and Jeanette Bolden. In all, he claimed 60 athletes with aspirations of expanding to 100. While actively promoting the sport in 1982, Chamberlain claimed he was considering a return to athletic competition, but not in basketball, in Masters athletics. At the time he claimed he had only been beaten in the high jump once, by Olympic champion Charles Dumas, and that he had never been beaten in the shot put, including beating Olympic legend Al Oerter.[110]

Chamberlain played a villainous warrior and counterpart of Arnold Schwarzenegger in the film Conan the Destroyer (1984). In November 1998, he signed with Ian Ng Cheng Hin, CEO of Northern Cinema House Entertainment (NCH Entertainment), to do his own bio-pic, wanting to tell his life story his way.[111]

He had been working on the screenplay notes for over a year at the time of his death. "He was more inquisitive than anybody I ever knew. He was writing a screenplay about his life. He was interested in world affairs, sometimes he'd call me up late at night and discuss philosophy. I think he'll be remembered as a great man. He happened to make a living playing basketball but he was more than that. He could talk on any subject. He was a Goliath", said Sy Goldberg, Chamberlain's longtime attorney.[112] When million-dollar contracts became common in the NBA, Chamberlain increasingly felt he had been underpaid during his career.[113] A result of this resentment was the 1997 book Who's Running the Asylum? Inside the Insane World of Sports Today (1997), in which he harshly criticized the NBA of the 1990s for being too disrespectful of players of the past.[114] Even far beyond his playing days, Chamberlain was a very fit person. In his mid-forties, he was able to humble rookie Magic Johnson in practice,[115] and even in the 1980s, he flirted with making a comeback in the NBA. In the 1980–81 NBA season, coach Larry Brown recalled that the 45-year-old Chamberlain had received an offer from the Cleveland Cavaliers. When Chamberlain was 50, the New Jersey Nets had the same idea, but were declined.[115] However, he would continue to epitomize physical fitness for years to come, including participating in several marathons.[4]

Legacy

Chamberlain historical marker outside of Overbrook High School.

Individual achievements and recognition

Chamberlain is regarded as one of the most extraordinary and dominant basketball players in the history of the NBA.[116] The 1972 NBA Finals MVP is holder of numerous official NBA all-time records, establishing himself as a scoring champion, all-time top rebounder and accurate field goal shooter.[117] He led the NBA in scoring seven times, field goal percentage nine times, minutes played eight times, rebounding eleven times, and assists once.[118] He was also responsible for several rule changes, including widening the lane from 12 to 16 feet, as well as changes to rules regarding inbounding the ball[117] and shooting free throws.[119] Chamberlain is most remembered for his 100-point game,[120][121] which is widely considered one of basketball's greatest records.[122][123][124] Decades after his record, many NBA teams did not even average 100 points as fewer field goals per game were being attempted.[122] The closest any player has gotten to 100 points was the Los Angeles Lakers' Kobe Bryant, who scored 81 in 2006.[125][126][127] Bryant afterwards said Chamberlain's record was "unthinkable ... It's pretty exhausting to think about it."[128] Chamberlain's main weakness was his notoriously poor free throw shooting, where he has the third lowest career free throw percentage in NBA history with 51.1% (based on a minimum of 1,200 attempts). Chamberlain claimed that he intentionally missed free throws so a teammate could get the rebound and score two points instead of one,[129] but later acknowledged that he was a "psycho case" in this matter.[41] On the other hand, he committed surprisingly few fouls during his NBA career, despite his rugged play in the post. Chamberlain never fouled out of a regular season or playoff game in his 14-year NBA career. His career average was only two fouls per game, despite having averaged 45.8 minutes per game over his career. He had five seasons where he committed less than two fouls per game, with a career low of 1.5 fouls during the 1962 season, in which he also averaged 50.4 points per game. His fouls per 36 minutes (a stat used to compare players that average vastly different minutes) was a remarkable 1.6 per game.[2] "First he was a scorer. Then he was a rebounder and assist man. Then with our great Laker team in 1972, he concentrated on the defensive end", said Sharman.[130] In his two championship seasons, Chamberlain led the league in rebounding, while his scoring decreased to 24 and 15 points per game. By 1971–72 at age 35 and running less, his game had transformed to averaging only nine shots per game, compared to the 40 in his record-setting 1961–62 season.[118] He also had a signature 'Dipper' move, whereby he would fake a hook shot, and extend his arm to a short-range finger roll to shoot under a block attempt.[131] For his feats, Chamberlain was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1978, named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History, ranked #2 in SLAM Magazine's Top 50 NBA Players of All-Time[132] and #13 in the ESPN list "Top North American athletes of the century"[133] and voted the second best center of All-Time by ESPN behind Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on March 6, 2007.[134] During his career, Chamberlain competed against future Hall of Famers including Russell, Thurmond, Lucas, and Walt Bellamy. He later faced Unseld, Abdul-Jabbar, Dave Cowens, and Elvin Hayes.[135]

Chamberlain–Russell rivalry

Chamberlain being defended by the Celtics' Bill Russell, 1966.

From a historical NBA perspective, the rivalry between Chamberlain and his perennial nemesis Bill Russell is cited as the greatest on-court rivalry of all time.[5] There were three NBA Finals matchups in the rivalry between Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, but they played different positions and did not guard each other.[136] Russell's Celtics won seven of eight playoff series against Chamberlain's Warriors, 76ers, and Lakers teams, and went 57–37 against them in the regular season and 29–20 in the playoffs.[137] Russell's teams won all four seventh games against Chamberlain's—the combined margin was nine points.[118] Chamberlain outscored Russell 30 to 14.2 per game and outrebounded him 28.2 to 22.9 in the regular season, and also in the playoffs, he outscored him 25.7 to 14.9 and outrebounded him 28 to 24.7.[138] The comparison between the two is often simplified to a great player (Chamberlain) versus a player who makes his team great (Russell), an individualist against a team player. In 1961–62 when Chamberlain averaged 50.4 points per game, he noted that Boston did not rely on Russell's scoring, and he could concentrate on defense and rebounding. He wished people would understand that their roles were different. Chamberlain said, "I've got to hit forty points or so, or this team is in trouble. I must score—understand? After that I play defense and get the ball off the boards. I try to do them all, best I can, but scoring comes first."[139] Russell won 11 NBA titles in his career while Chamberlain won two.[140] Chamberlain was named All-NBA first team seven times to Russell's three, but Russell was named league MVP—then selected by players and not the press—five times against Chamberlain's four.[141] Russell and Chamberlain were friends in private life. Russell never considered Chamberlain his rival and disliked the term, instead pointing out that they rarely talked about basketball when they were alone. When Chamberlain died in 1999, Chamberlain's nephew stated that Russell was the second person he was ordered to break the news to.[142] The two did not speak for two decades after Russell criticized Chamberlain after Game 7 of the 1969 Finals. Russell apologized privately to him and later publicly.[143]

Rule changes

Chamberlain's impact on the game is also reflected in the fact that he was directly responsible for several rule changes in the NBA, including widening the lane to try to keep big men farther away from the hoop, instituting offensive goaltending and revising rules governing inbounding the ball and shooting free throws (such as making it against the rules to inbound the ball over the backboard).[2][144] Chamberlain, who reportedly had a 50-inch vertical leap,[145] was physically capable of converting foul shots via a slam dunk without a running start (beginning his movement at the top of the key).[146] When his dunks practically undermined the difficulty of a foul shot, both the NCAA[147] and the NBA banned his modus operandi.[2][115] In basketball history, pundits have stated that the only other player who forced such a massive change of rules is 6'10" Minneapolis Lakers center George Mikan, who played a decade before Chamberlain and also caused many rule changes designed to thwart so-called "big men".[148]

Reputation

Although Chamberlain racked up some of the most impressive statistics in the history of Northern American professional sports, because he won "just" two NBA championships and lost seven out of eight playoff series against the Celtics teams of his on-court nemesis Bill Russell, Chamberlain was often called "selfish" and a "loser".[149]Frank Deford of ESPN said that Chamberlain was caught in a no-win situation: "If you win, everybody says, 'Well, look at him, he's that big.' If you lose, everybody says, 'How could he lose, a guy that size?' "[22] Chamberlain himself often said: "Nobody roots for Goliath."[4] Like later superstar Shaquille O'Neal, Chamberlain was a target of criticism because of his poor free throw shooting, a .511 career average, with a low of .380 over the 1967–68 season.[43] Countless suggestions were offered; he shot them underhanded, one-handed, two-handed, from the side of the circle, from well behind the line, and even banked in. Sixers coach Alex Hannum once suggested he shoot his famous fadeaway jumper as a free throw, but Chamberlain feared drawing more attention to his one great failing.[36] Despite his foul line woes, Chamberlain set the NBA record (28) for free throws made in a regular season game in his 1962 100-point game.[note 2][150]